Issue 3 March 2005 - BASES

Issue 3 March 2005 - BASES

Issue 3 March 2005 - BASES

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE<br />

made the mistake of assuming otherwise.<br />

I now consider intervention checks, formal<br />

and/or informal, as critical to evaluating my<br />

effectiveness. These checks range from formal<br />

paper-based evaluation forms completed<br />

anonymously by both athletes and support staff<br />

to an informal question such as, “What did you<br />

think of that session?” As rapport and trust<br />

builds up, I found individuals to be fairly<br />

honest in their appraisals.<br />

Additionally, as a result of my initial ‘waste-oftime’<br />

group adherence workshop session I<br />

decided in future to run group sessions only if I<br />

considered it to be the most appropriate<br />

intervention format. My view is that it’s difficult<br />

to be effective if you can’t work on an<br />

individual basis. Early in my career I would take<br />

whatever sessions were made available, keen<br />

for whatever experiences I could get. But I<br />

wouldn’t run a session unless a coach was<br />

prepared to allow adequate time and priority for<br />

me to do a job properly. All too often I notice<br />

that sport science workshops are timetabled<br />

late in the evening when athletes would rather<br />

rest and recover. By continually agreeing to<br />

work the ‘graveyard slot’ I think the role of<br />

sport science in positively impacting on<br />

performance is in danger of being devalued. I<br />

think the important thing is to not always agree<br />

straight away to running a session, particularly<br />

if you think the timing is not ideal. This does<br />

not mean being unaccommodating but in my<br />

experience, by challenging the timetable and<br />

requesting more time I actually gained<br />

credibility.<br />

3. You won’t know you have a problem<br />

unless you look<br />

I soon learned that the prescription of a training<br />

programme does not ensure the adoption and<br />

maintenance of the target behaviours, even in<br />

high-level sport groups where motivation is<br />

often assumed to be high. Provision of a fitness<br />

training programme should represent only an<br />

initial stage of an intervention and monitoring<br />

both training adherence behaviour and fitness<br />

is important. Most sports now monitor training<br />

adherence via various methods, including<br />

training diaries, some of which are now webbased<br />

or can be completed electronically. In<br />

terms of good practice, it is important that the<br />

athlete is made aware of who will have access<br />

to this diary information and how it will be<br />

used, especially in terms of the<br />

development/selection process. Otherwise this<br />

could lead to problems with confidentiality and<br />

fabrication of data.<br />

What is monitored, in terms of training and<br />

fitness, and how it is undertaken undoubtedly<br />

influences training behaviour. I will use a story<br />

regarding the ‘bleep test’ to illustrate how the<br />

use of one test dramatically influenced training<br />

behaviour. In the fitness testing in which I was<br />

involved, the bleep test was the first test to be<br />

performed and all the coaches would watch<br />

this one test before disappearing off to various<br />

planning meetings. This selective coach<br />

observation was soon noticed by athletes and<br />

as a consequence, performance in the bleep<br />

test was massively over-emphasised and took<br />

on the only definition of ‘fitness’. However,<br />

once aware of this issue, the coaches soon<br />

changed their behaviour.<br />

But is it a coincidence that there was a trend to<br />

‘over-adhere’ to aerobic fitness training and<br />

‘under-adhere’ with other types of training such<br />

as speed and power? Whilst there are many<br />

possible explanations for these over- and<br />

under-adherence findings, my own thoughts are<br />

that the myth of defining fitness by<br />

performance on one test certainly contributed.<br />

My aim here is to debate neither the<br />

advantages of certain fitness tests over others,<br />

nor the merits of laboratory versus field-based<br />

testing, but rather to highlight the need to<br />

carefully select appropriate tests, not just<br />

fitness ones, and ensure their relative<br />

importance is clearly communicated to all,<br />

including key support staff.<br />

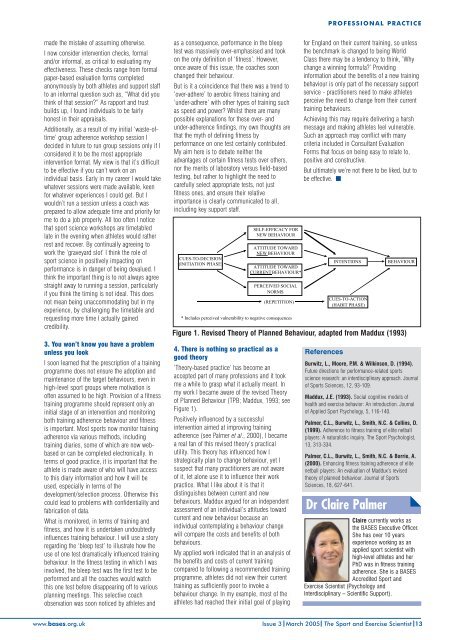

CUES-TO-DECISION<br />

(INITIATION PHASE)<br />

SELF-EFFICACY FOR<br />

NEW BEHAVIOUR<br />

ATTITUDE TOWARD<br />

NEW BEHAVIOUR<br />

ATTITUDE TOWARD<br />

CURRENT BEHAVIOUR*<br />

PERCEIVED SOCIAL<br />

NORMS<br />

(REPETITION)<br />

* Includes perceived vulnerability to negative consequences<br />

4. There is nothing so practical as a<br />

good theory<br />

‘Theory-based practice’ has become an<br />

accepted part of many professions and it took<br />

me a while to grasp what it actually meant. In<br />

my work I became aware of the revised Theory<br />

of Planned Behaviour (TPB; Maddux, 1993; see<br />

Figure 1).<br />

Positively influenced by a successful<br />

intervention aimed at improving training<br />

adherence (see Palmer et al., 2000), I became<br />

a real fan of this revised theory’s practical<br />

utility. This theory has influenced how I<br />

strategically plan to change behaviour, yet I<br />

suspect that many practitioners are not aware<br />

of it, let alone use it to influence their work<br />

practice. What I like about it is that it<br />

distinguishes between current and new<br />

behaviours. Maddux argued for an independent<br />

assessment of an individual’s attitudes toward<br />

current and new behaviour because an<br />

individual contemplating a behaviour change<br />

will compare the costs and benefits of both<br />

behaviours.<br />

My applied work indicated that in an analysis of<br />

the benefits and costs of current training<br />

compared to following a recommended training<br />

programme, athletes did not view their current<br />

training as sufficiently poor to invoke a<br />

behaviour change. In my example, most of the<br />

athletes had reached their initial goal of playing<br />

for England on their current training, so unless<br />

the benchmark is changed to being World<br />

Class there may be a tendency to think, ’Why<br />

change a winning formula?’ Providing<br />

information about the benefits of a new training<br />

behaviour is only part of the necessary support<br />

service - practitioners need to make athletes<br />

perceive the need to change from their current<br />

training behaviours.<br />

Achieving this may require delivering a harsh<br />

message and making athletes feel vulnerable.<br />

Such an approach may conflict with many<br />

criteria included in Consultant Evaluation<br />

Forms that focus on being easy to relate to,<br />

positive and constructive.<br />

But ultimately we’re not there to be liked, but to<br />

be effective. ■<br />

References<br />

INTENTIONS<br />

CUES-TO-ACTION<br />

(HABIT PHASE)<br />

Burwitz, L., Moore, P.M. & Wilkinson, D. (1994).<br />

Future directions for performance-related sports<br />

science research: an interdisciplinary approach. Journal<br />

of Sports Sciences, 12, 93-109.<br />

Maddux, J.E. (1993). Social cognitive models of<br />

health and exercise behavior: An introduction. Journal<br />

of Applied Sport Psychology, 5, 116-140.<br />

Palmer, C.L., Burwitz, L., Smith, N.C. & Collins, D.<br />

(1999). Adherence to fitness training of elite netball<br />

players: A naturalistic inquiry. The Sport Psychologist,<br />

13, 313-334.<br />

Palmer, C.L., Burwitz, L., Smith, N.C. & Borrie, A.<br />

(2000). Enhancing fitness training adherence of elite<br />

netball players: An evaluation of Maddux’s revised<br />

theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Sports<br />

Sciences, 18, 627-641.<br />

Dr Claire Palmer<br />

BEHAVIOUR<br />

Figure 1. Revised Theory of Planned Behaviour, adapted from Maddux (1993)<br />

Claire currently works as<br />

the <strong>BASES</strong> Executive Officer.<br />

She has over 10 years<br />

experience working as an<br />

applied sport scientist with<br />

high-level athletes and her<br />

PhD was in fitness training<br />

adherence. She is a <strong>BASES</strong><br />

Accredited Sport and<br />

Exercise Scientist (Psychology and<br />

Interdisciplinary – Scientific Support).<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist 13