Issue 3 March 2005 - BASES

Issue 3 March 2005 - BASES

Issue 3 March 2005 - BASES

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

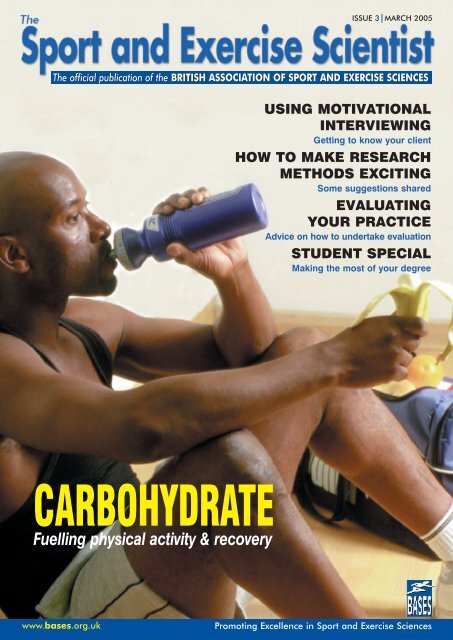

ISSUE 3 MARCH <strong>2005</strong><br />

The official publication of the BRITISH ASSOCIATION OF SPORT AND EXERCISE SCIENCES<br />

USING MOTIVATIONAL<br />

INTERVIEWING<br />

Getting to know your client<br />

HOW TO MAKE RESEARCH<br />

METHODS EXCITING<br />

Some suggestions shared<br />

EVALUATING<br />

YOUR PRACTICE<br />

Advice on how to undertake evaluation<br />

STUDENT SPECIAL<br />

Making the most of your degree<br />

CARBOHYDRATE<br />

Fuelling physical activity & recovery<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport Scientist<br />

Promoting Excellence in Sport and Exercise Sciences

FOREWORD<br />

The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

The SES is published quarterly by <strong>BASES</strong><br />

Editor l Dr Chris Sellars<br />

Production Director l Dr Claire Palmer<br />

Book and Resource Review Editor l Dr Keith Tolfrey<br />

Editorial Advisory Board l Lisa Board, Tracey Devonport,<br />

Prof Andy Lane, Dr Sarah Rowell, Dr John Saxton<br />

Advertising l Dr Claire Palmer<br />

Tel/ Fax:+44 (0)113 289 1020 • cpalmer@bases.org.uk<br />

Publisher l Mercer Print, Newark Street, Accrington BB5 0PB<br />

Tel: +44 (0)1254 395512<br />

info@mercer-print.co.uk<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> l Chelsea Close, Off Amberley Road, Armley,<br />

Leeds, LS12 4HP • Tel/ Fax: +44 (0)113 289 1020<br />

jbairstow@bases.org.uk<br />

Website l www.bases.org.uk<br />

is sponsored by Human Kinetics, www.HumanKinetics.com<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> is supported by UK Sport.<br />

Disclaimer l The statements and opinions contained in the articles<br />

are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and are<br />

not necessarily those of <strong>BASES</strong>. The appearance of advertisements<br />

in the publication is not a warranty, endorsement or approval of<br />

products or services. <strong>BASES</strong> has undertaken all reasonable<br />

measures to ensure that the information contained in The SES is<br />

accurate and specifically disclaims any liability, loss or risk, personal<br />

or otherwise, which is incurred as a consequence, directly or<br />

indirectly of the use and application of any of the contents.<br />

Copyright © <strong>BASES</strong>, <strong>2005</strong> l All rights reserved. Reproduction in<br />

whole or in substantial part without permission of The SES<br />

Production Director is strictly prohibited. An archive of the The SES<br />

is available in the Member Area at ■ www.bases.org.uk<br />

Copy deadline 12 May <strong>2005</strong> for <strong>Issue</strong> 4 June <strong>2005</strong>. All contributions<br />

welcomed. Info for contributors ■ www.bases.org.uk<br />

Front Cover Photograph l Courtesy of The Sugar Bureau.<br />

Dr CHRIS SELLARS<br />

Editor<br />

The Sport and<br />

Exercise Scientist<br />

In this our third issue of The SES, we have a range of material that<br />

spans applied practice, research, and teaching and learning in sport and<br />

exercise science. In line with useful suggestions and feedback from<br />

readers, we have attempted to further integrate reflection on one’s own<br />

and others’ practices, while at the same time building on the publication’s<br />

themes that I hope are becoming familiar.<br />

Our feature article explores the role of carbohydrates in fuelling exercise<br />

and recovery, providing valuable advice on suitable food types and eating<br />

strategies. This is supported by articles on motivational interviewing, how<br />

to make the teaching of research methods more effective, the use of<br />

software to aid qualitative research, and examining ways of evaluating<br />

your practice. We also have an interview with sport and exercise scientist<br />

turned Olympic cycling coach Simon Jones.<br />

We also have two contributions that focus specifically on personal<br />

reflections in relation to aspects of the contributor’s work - one discussing<br />

the lessons learned from applied sport science practice and the other<br />

considering the contribution of personal development planning within<br />

sport and exercise science. New to this issue, we have an ‘Ask the<br />

Practitioner’ section, where two <strong>BASES</strong> accredited sport and exercise<br />

scientists comment on a case presented by a probationary sport and<br />

exercise scientist. The ‘special’ in this issue may be of specific interest to<br />

our student members in relation to making the most of their degree<br />

when applying for jobs or postgraduate training. This section incorporates<br />

testimonials from two recent graduates who share their tips on how to<br />

get ahead.<br />

We also have a summary of <strong>BASES</strong>’ recent EGM, the outcomes of which<br />

will result in some significant, challenging and exciting changes to the<br />

Association.<br />

I have had some encouraging communications from readers over the last<br />

few months, so please keep it coming! ■<br />

Dr Chris Sellars<br />

Editor<br />

■ c.sellars@hud.ac.uk<br />

CONTENTS<br />

4 CARBOHYDRATES –<br />

THE PROS AND CONS IN RELATION TO PERFORMANCE<br />

Dr Samantha Stear evaluates the<br />

significance of carbohydrate consumption<br />

6 NEWS<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> and AAASP Collaboration, New accreditation<br />

system for exercise science practitioners, <strong>BASES</strong><br />

relocating to Leeds Metropolitan University, CCPR<br />

challenge to Government<br />

8 EXERCISE MOTIVATION AND ADHERENCE: THE USE<br />

OF MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING<br />

Jeff Breckon discusses this<br />

approach to behaviour change<br />

10 MAKING RESEARCH METHODS MORE ‘ATTRACTIVE’<br />

TO SPORT & EXERCISE SCIENCE STUDENTS<br />

Dr Clare Hencken discusses some of her experiences<br />

of designing and teaching research methods<br />

12 CHANGING ATHLETES BEHAVIOUR<br />

Dr Claire Palmer reflects on lessons learned from<br />

her own applied practice<br />

14 <strong>BASES</strong> WORKSHOPS & DATES FOR THE DIARY<br />

15 STUDENT SPECIAL<br />

Making the most of your<br />

sport & exercise science degree<br />

19 REVIEWS<br />

Latest books reviewed<br />

21 LETTERS<br />

22 INTERVIEW WITH<br />

DR SIMON JONES<br />

Dr Simon Jones reflects on his<br />

transition to Olympic cycling coach<br />

23 TOP TIPS<br />

24 REFLECTIONS ON THE USE OF<br />

QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS SOFTWARE:<br />

IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING AND LEARNING<br />

Dr Lynne Johnston shares her experiences of<br />

using software such as NVivo and QSR NUD*IST<br />

26 <strong>BASES</strong> EGM<br />

A new chapter in the history of <strong>BASES</strong> has opened<br />

27 UK SPORT PRACTITIONER<br />

DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME<br />

Dr John Bradley describes<br />

his experiences<br />

28 EVALUATING PRACTICE IN SPORT<br />

AND EXERCISE SCIENCE<br />

Dr Nick Smith and Phil Moore<br />

draw on their own experiences of<br />

evaluating practice<br />

30 ASK THE PRACTITIONER<br />

Two accredited sport & exercise<br />

scientists comment on case material<br />

4<br />

30<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist 3

FEATURE<br />

Carbohydrates<br />

- the pros and cons in relation to performance<br />

Dr Samantha Stear examines the importance of carbohydrate intake and makes<br />

recommendations in relation to sport and physical activity performance<br />

LIFE in competitive sport revolves around training<br />

and competition. To be able to sustain training as<br />

well as strive for performance improvements, it is<br />

essential to optimise recovery between one<br />

training session and the next. But why is there<br />

such a huge emphasis on carbohydrates?<br />

Carbohydrate is the preferred energy fuel for the muscles, because it<br />

is the only fuel that can power intense exercise for prolonged<br />

periods. All carbohydrates, both sugars and starches, are converted<br />

to glucose and stored as glycogen in the muscles and liver.<br />

However, the body's glycogen stores are limited so need to be<br />

topped-up regularly to supply and restock fuel for training.<br />

It is important to make carbohydrate-rich foods the focus of the<br />

training diet, because only carbohydrates are stored as glycogen<br />

and depleted stores are associated with fatigue. Unfortunately, due<br />

to the popularity of the low-carbohydrate diets, such as Atkins and<br />

South Beach diets, many athletes, from recreational to elite, are<br />

suffering with needless fatigue. Eating insufficient carbohydrates is<br />

likely to lead to energy deficiency, which not only puts performance,<br />

but also health, at risk.<br />

So the pro-side is relatively straightforward - carbohydrates are the<br />

key nutrient for energy supply. But what about the cons? In simple<br />

terms there aren't any. The con-side needs a slightly different<br />

approach with regards to how the type, amount and timing of<br />

carbohydrate intake may affect performance. Although the details<br />

regarding these issues will be discussed in terms of the recent IOC<br />

Consensus Conference on Sports Nutrition (Maughan, Burke &<br />

Coyle, 2004), it is important to bear in mind that specifics are down<br />

to the individual and the exercise or sporting situation.<br />

Energy deficiency related health risks<br />

Total dietary energy intake needs to be increased to compensate for<br />

the energy used-up during training and competition. However, many<br />

athletes, particularly females and individuals who compete in<br />

endurance and aesthetic sports, and sports with weight categories,<br />

do not adequately compensate for their exercise energy expenditure<br />

and so end-up chronically energy deficient. Energy deficiency<br />

impairs performance, growth and health. It has been shown that<br />

metabolic and reproductive disorders in athletes, especially females,<br />

are caused by low energy availability, particularly low carbohydrate<br />

availability, and not by the stress of exercise (Loucks, 2004). Energy<br />

availability is defined as dietary energy intake minus exercise energy<br />

expenditure.<br />

For athletes expending large amounts of energy during training,<br />

neither an eating disorder nor dietary restriction is necessary to<br />

induce reproductive disorders. Therefore, athletes can prevent this<br />

and restore metabolic and reproductive function through dietary<br />

supplementation to compensate for exercise energy expenditure<br />

without any modification to the training regimen, or indeed other<br />

stresses. So training can continue providing athletes are willing to<br />

eat!<br />

There is strong evidence that in order to protect metabolic,<br />

reproductive and skeletal health, energy availability (EA) should not<br />

fall below 30kcal per kg fat free mass (FFM) per day (Loucks, 2004).<br />

Table 1 shows some examples of low energy availability that fall<br />

below the 30kcal per kg of FFM per day.<br />

Table 1. Examples of low energy availability (EA) that fall below the<br />

30kcal per kg of FFM per day *<br />

Athlete description<br />

Female, 60kg with 20% body<br />

fat FFM = 48kg (60 x 0.80)<br />

Trains 1.5 hours per day<br />

Male, 75 kg with 12% body fat<br />

FFM = 66kg (75 x 0.88)<br />

Trains 2.25 hours per day<br />

(*Reproduced from Fuelling Fitness for Sports Performance)<br />

Amount of carbohydrate<br />

The key aspect of the daily diet during training is to ensure that it<br />

provides the muscles with substrates to fuel training to attain optimal<br />

adaptation and performance enhancements. Availability of<br />

carbohydrate as a substrate for the muscle and central nervous<br />

system is essential for exercise performance, particularly during<br />

prolonged sessions (>90 minutes) and as exercise intensity<br />

increases.<br />

Carbohydrate intake must be adequate to meet the fuel requirements<br />

of training and to optimise recovery of glycogen stores between<br />

training sessions. General daily carbohydrate targets can be<br />

provided in terms of body size and training level, but should be<br />

tailored to suit individual energy and training needs, and feedback<br />

from training performance (Burke, Kiens & Ivy, 2004). Table 2 gives<br />

daily carbohydrate targets in terms of grams per kg body weight as<br />

this is more closely related to the muscles' absolute need for fuel.<br />

Table 2. Carbohydrate recommendations for training*<br />

Training level<br />

Dietary<br />

energy<br />

intake (a)<br />

Regular levels of activity (3-5 hrs/week)<br />

Moderate duration/low-intensity training (1-2 hrs/day)<br />

Moderate to heavy endurance training (2-4+ hrs/day)<br />

Extreme exercise programme (4-6+ hrs/day)<br />

Carbohydrate<br />

g/kg body<br />

weight/day<br />

4 - 5<br />

5 - 7<br />

7 - 12<br />

10 - 12<br />

(*Reproduced from Fuelling Fitness for Sports Performance)<br />

It is essential that athletes are realistic as to how long and how hard<br />

they are training. Inadequate carbohydrate fuel will diminish glycogen<br />

stores and result in fatigue. This in turn increases the risk of illness<br />

and injury. In female athletes, metabolic and reproductive function is<br />

disrupted following only a few days of low carbohydrate availability,<br />

putting both health and performance at risk.<br />

Conversely, too high an energy intake, regardless of nutrient (calories<br />

count), could lead to an increase in body fat. For many, this is<br />

opposite to the goal of reducing body fat. In sport – size matters!<br />

The right dietary intakes will help athletes achieve a sport specific<br />

optimal body size and body composition, and the optimal mix of fuel<br />

stores to enhance exercise performance.<br />

4 <strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

2100<br />

kcal<br />

3800<br />

kcal<br />

Energy used<br />

in exercise<br />

(b)<br />

800<br />

kcal<br />

1950 kcal<br />

EA<br />

(a-b)<br />

1300<br />

kcal<br />

1850<br />

kcal<br />

EA/<br />

FFM<br />

27<br />

28

FEATURE<br />

Type of carbohydrate<br />

It is important to choose nutrient-rich<br />

carbohydrate foods and to add other foods<br />

to recovery meals and snacks, to provide a<br />

good source of protein and other nutrients.<br />

The bulk of carbohydrate intake should<br />

come from the cereal and starchy sources -<br />

the main ones being breads, potatoes, rice,<br />

pasta, breakfast cereals, plus the less<br />

common starchy vegetables and pulses<br />

such as yams, plantains, peas, beans and<br />

lentils. The remaining intake can come from<br />

more sugary sources such as<br />

sugar, fruit and juices.<br />

As most carbohydrate foods, Refuelling<br />

for example potatoes or<br />

sugars, are eventually<br />

broken down into glucose,<br />

one type is not intrinsically<br />

better than the other.<br />

Research has shown that a<br />

diet high in carbohydrate,<br />

obtained either from simple<br />

sugars or complex carbohydrates, is<br />

equally effective in improving exercise<br />

performance. However, perhaps what is more<br />

important is how quickly the carbohydrate is<br />

converted to glucose - its glycaemic index<br />

(GI).<br />

The GI of a food is a measure of that food’s<br />

effect on blood glucose levels. It is worked<br />

out by comparing the rise in blood glucose<br />

after consuming a food containing 50g of<br />

carbohydrate with the blood glucose rise<br />

after consuming 50g of a reference<br />

carbohydrate (usually glucose). The faster<br />

the rise in blood glucose, the higher the GI<br />

(and generally the greater the insulin<br />

response). In general, foods are divided into<br />

three categories – high, moderate and low<br />

GI. Unfortunately, there is no easy way to tell<br />

what the GI of a food is. Some sugars have<br />

a high GI (glucose) and others a low GI<br />

(fructose). Some complex carbohydrates<br />

have a low GI (pasta) whereas others have a<br />

higher GI (rice). Several characteristics can<br />

lower the GI of food such as high fructose,<br />

fibre or fat content.<br />

Carbohydrate-rich foods with a moderate to<br />

high GI provide a fast and readily available<br />

source of carbohydrate for glycogen storage<br />

and therefore are the best fuel choice during<br />

exercise and should also be the major fuel<br />

choice in the immediate recovery period (0-4<br />

hours after exercise) to boost post-exercise<br />

refuelling (Burke et al., 2004). Conversely,<br />

the rate of glucose supply to the<br />

bloodstream from the digestion of low GI<br />

carbohydrate foods is generally not fast<br />

enough while exercising. However,<br />

consuming low GI carbohydrates 3-4 hours<br />

prior to prolonged exercise may help sustain<br />

delivery of carbohydrate during the exercise<br />

period.<br />

One of the problems with low GI<br />

carbohydrate foods may be more due to the<br />

presence of dietary fibre, resulting in a<br />

considerable proportion of indigestible<br />

carbohydrate. This means that although the<br />

food in theory supplies a certain amount of<br />

The<br />

Sugar Bureau<br />

carbohydrate, some is malabsorbed, and is<br />

therefore not available to the muscles for<br />

refuelling. So, if low GI carbohydrate foods<br />

are a more normal dietary pattern, then a<br />

greater amount of carbohydrates need to be<br />

consumed to take account of the<br />

indigestible proportion.<br />

Timing of carbohydrate intake<br />

Consuming a carbohydrate-rich meal 3-4<br />

hours before exercise can increase glycogen<br />

stores and so is generally thought to<br />

enhance exercise performance<br />

(Hargreaves, Hawley &<br />

Jeukendrup, 2004). Pre-exercise<br />

carbohydrate-rich meals can<br />

help stock inadequate muscle<br />

glycogen stores and restore<br />

liver glycogen stores, which<br />

get depleted during the night.<br />

Restoring liver glycogen is<br />

particularly important before<br />

morning training sessions or<br />

competition. If time is limited prior to<br />

exercising in the morning, then an alternative<br />

option is to have a lighter meal or snack and<br />

continue to consume carbohydrates during<br />

exercise to balance missed fuelling<br />

opportunities.<br />

Consuming a carbohydrate-rich snack 30-60<br />

minutes before exercise can be beneficial for<br />

some individuals providing enough<br />

carbohydrate, ideally 70–100g, is consumed<br />

without causing unnecessary gastrointestinal<br />

distress (Hargreaves et al., 2004). This must<br />

be assessed on an individual basis to<br />

ensure that it can be done without inducing<br />

the negative consequences of<br />

hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose levels) in<br />

susceptible individuals.<br />

If pre-exercise carbohydrate is the only<br />

means of increasing carbohydrate availability<br />

during exercise, then it is important that a<br />

substantial amount (>70g) is consumed.<br />

Problems regarding carbohydrate<br />

consumption prior to exercise arise when too<br />

little carbohydrate (40 minutes) it is often<br />

beneficial to continue to ingest carbohydrate<br />

at a rate of 30-60g·h-1 throughout exercise<br />

to help maintain the flow of glucose.<br />

During exercise that lasts for longer than an<br />

hour and which elicits fatigue, it is advisable<br />

to consume rapidly-absorbable (moderatehigh<br />

GI) carbohydrates at a rate of 30-60g·h-<br />

1, because this generally improves<br />

performance. This intake is best achieved by<br />

regular feedings every 10-30min, depending<br />

on what is allowed during competition, and<br />

should be continued throughout exercise to<br />

provide a steady flow of glucose into the<br />

blood stream (Coyle, 2004). Again, fructose<br />

intake should be limited to amounts that do<br />

not cause gastrointestinal distress.<br />

After exercise carbohydrates need to be<br />

consumed to ensure successful refuelling<br />

and restocking of glycogen stores between<br />

training sessions. Highest rates of glycogen<br />

storage occur in the first few hours (0-4<br />

hours) after exercise, so it is particularly<br />

important to consume carbohydrates as<br />

soon as is practically possible when<br />

recovery time is short (less than 8 hours)<br />

between training sessions. Moderate to high<br />

GI carbohydrates should be consumed in<br />

the immediate recovery period to optimise<br />

glucose uptake for glycogen storage and<br />

then low GI carbohydrates can be phased in<br />

for the remaining recovery period.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Dietary carbohydrate intake needs to be<br />

adequate to supply and restock fuel for<br />

training. It is vital to get the energy intake<br />

right – too much or too little can have an<br />

adverse impact on health and performance.<br />

The total amount of carbohydrate consumed<br />

is the most important dietary factor in terms<br />

of restocking glycogen stores. Other dietary<br />

strategies such as timing of intake, type of<br />

carbohydrate, or addition of other nutrients,<br />

may either directly enhance glycogen<br />

recovery or improve the practical aspects of<br />

achieving carbohydrate intake targets. It is<br />

important that any new fuelling strategies are<br />

experimented with during training,<br />

particularly ingestion of carbohydrates<br />

before and during exercise, to find out what<br />

works for the individual and also for each<br />

specific exercise or sporting situation. ■<br />

References<br />

Burke, L.M., Kiens, B. & Ivy, J.L. (2004).<br />

Carbohydrates and fat for training and recovery. Journal of<br />

Sports Sciences, 22, 15-30.<br />

Hargreaves, M., Hawley, J.A. & Jeukendrup, A.<br />

(2004). Pre-exercise carbohydrate and fat ingestion:<br />

effects on metabolism and performance. Journal of Sports<br />

Science, 22, 31-38.<br />

Loucks, A.B. (2004). Energy balance and body<br />

composition in sports and exercise. Journal of Sports<br />

Sciences, 22, 1-14.<br />

Maughan, R.J., Burke, L.M. & Coyle, E.F. (2004).<br />

Food, Nutrition and Sports Performance II.<br />

London:Routledge.<br />

The full manuscripts from the International Olympic<br />

Committee (IOC) Consensus Conference on Sports<br />

Nutrition have been published as a Special <strong>Issue</strong> of the<br />

Journal of Sports Sciences, January 2004 and are also<br />

available in Maughan et al., 2004.<br />

Dr Samantha Stear<br />

Sam is a Registered Sport and<br />

Exercise Nutritionist with a<br />

biomedical science degree from<br />

University College London, a<br />

masters degree in nutrition from<br />

King’s College London, and a<br />

PhD from Cambridge University.<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

5

NEWS<br />

NEWS IN BRIEF<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> Annual Conference<br />

locations announced<br />

The 2006 and 2007 <strong>BASES</strong> Annual Conferences have<br />

been awarded to the University of Wolverhampton and<br />

the University of Bath respectively. Heriot Watt University<br />

will host the 2006 <strong>BASES</strong> Annual Student Conference.<br />

Chair of K 46, the Sports Related<br />

Studies RAE 2008 Sub-panel,<br />

appointed<br />

The four UK higher education funding bodies have<br />

announced the chairs of the 67 sub-panels for<br />

Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) 2008. Prof<br />

Clyde Williams, Loughborough University and<br />

previous Chair of <strong>BASES</strong>, has been appointed the<br />

Chair of K 46, the Sports Related Studies RAE<br />

Panel. ■ www.rae.ac.uk<br />

New Midlands Sport & Exercise<br />

Psychology Network<br />

The Midlands Sport & Exercise Psychology Network is a<br />

new forum for individuals living in the midlands of England.<br />

Its purpose is to facilitate communication, dissemination of<br />

good practice, and continuing professional development.<br />

The network is co-directed by Dr Dan Weigand at<br />

University College Northampton<br />

■ daniel.weigand@northampton.ac.uk<br />

and Dr Chris Harwood at Loughborough University<br />

■ c.g.harwood@lboro.ac.uk<br />

Course Finder update<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> has received a high level of interest in<br />

this important initiative. The course finder lists<br />

details of over 260 courses available at 36<br />

universities.<br />

The course finder has received over 15,000<br />

page hits so far.<br />

■ www.bases.org.uk/newsite/coursesearch.asp<br />

Journal of Sports Sciences Editorials<br />

now in member area<br />

A selection of Editorials from the Journal of Sports<br />

Sciences has been added to the Member Area of the<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> website ■ www.bases.org.uk<br />

Abstract submission goes on-line<br />

On-line abstract submission forms were<br />

developed for both the <strong>2005</strong> <strong>BASES</strong> Annual and<br />

Student Conferences. The on-line abstract<br />

submission form for the Annual Conference was<br />

developed in association with Taylor & Francis.<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> weekly email newsletter<br />

Please ensure that the <strong>BASES</strong> Office has your correct<br />

Email address as the Email newsletter is now the key<br />

communication tool for <strong>BASES</strong>.<br />

The deadline for News and News in Brief items<br />

for the next issue of The SES is 12 May.<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> and AAASP Reach<br />

Collaboration Agreement<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> and the Association for the Advancement of Applied<br />

Sport Psychology (AAASP) have<br />

developed a Memorandum of<br />

Collaboration (MoC) aimed to<br />

enhance the developing alliance<br />

between the two associations.<br />

AAASP specialises in promoting<br />

research and consulting excellence in applied sport, exercise and<br />

health psychology. AAASP and <strong>BASES</strong> share a common goal of<br />

ensuring that all athletes, coaches and those in the community<br />

that participate in sport and exercise benefit from the highest<br />

quality provision of psychological services.<br />

Building on cooperation in the area of sport and exercise<br />

psychology over several years, <strong>BASES</strong> and AAASP have<br />

recently developed a reciprocity agreement, which<br />

recognises the equivalence of <strong>BASES</strong> Accreditation and<br />

AAASP Certification. Furthermore, <strong>BASES</strong> and AAASP will<br />

collaborate on joint continuous professional development<br />

opportunities and will develop enhanced benefits for<br />

members of both associations through economies of scale.<br />

New accreditation system for<br />

exercise science practitioners<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> is developing a new accreditation category to add to its<br />

existing peer-reviewed sport & exercise scientist accreditation<br />

programme. This new category of Accredited Exercise Science<br />

Practitioner aims to provide the recognised standard for exercise<br />

scientists working in areas of outpatient rehabilitation, exercise<br />

referrals and physical activity advisory services. It is aimed at the<br />

individual who possesses a sport and exercise science degree, and<br />

has also demonstrated practice experience and attained relevant<br />

practical or vocational standards. It aims to assist health and leisure<br />

service (public or private) providers who want to employ a person<br />

with this background but where currently there is no identified<br />

common standard.<br />

The accreditation process is about demonstrating the ability to<br />

integrate knowledge, experience and practice/vocational skills into<br />

one recognised qualification. Within this the Practitioner can<br />

demonstrate a speciality (e.g., cardiac rehabilitation) but also needs<br />

skills and knowledge to at least advise or direct clients with needs<br />

outside his/her speciality (similar to a GP in medicine). The<br />

accreditation is aimed to integrate such vocational standards as<br />

those developed by Skills Active and Skills for Health. This initiative is<br />

being led by Dr John Buckley.<br />

CCPR launches challenge to<br />

Government<br />

The CCPR has launched the ‘Challenge’ and ‘Physical Education Declaration’.<br />

The Challenge calls upon the next government to place sport and recreation<br />

higher on the political agenda and seeks a genuine commitment for more<br />

sustained support and financial investment in the UK’s sports system.<br />

The Physical Education Declaration, issued by the National Physical<br />

Education Summit on 24 January, calls on the Government and key delivery<br />

agencies to invest more time for initial teacher training and professional<br />

development, and to review the nature of training to meet 21st Century<br />

needs. ■ www.ccpr.org.uk<br />

6<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

www.bases.org.uk

<strong>BASES</strong> are relocating to Leeds<br />

Metropolitan University<br />

In May <strong>2005</strong> <strong>BASES</strong> will be<br />

moving its Head Office to<br />

the Headingley Campus at<br />

Leeds Metropolitan<br />

University.<br />

Prof Craig Mahoney, Chair of<br />

<strong>BASES</strong>, said, “I am delighted that<br />

we have been able to relocate the<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> Head Office onto the<br />

campus of Leeds Metropolitan<br />

University. The potential this offers<br />

us in the development of the<br />

Association, the links with Higher<br />

Education, sport and associated<br />

agencies will undoubtedly be of<br />

long term benefit to both <strong>BASES</strong><br />

and the University. I think the desire<br />

to stay in Leeds, where we are<br />

known, respected and have good<br />

contact support, was key in making<br />

this move. The environmental<br />

conditions and support structures of<br />

the University will also add to the<br />

further development of the<br />

Association in this time of change<br />

and restructuring.”<br />

Prof Carlton Cooke, Associate Dean<br />

and Head of the School of Sport,<br />

Exercise and Physical Education,<br />

added, "We are delighted<br />

to welcome <strong>BASES</strong> onto<br />

our Headingley Campus at Leeds<br />

Metropolitan University. The offices<br />

will be located in Fairfax Hall, which<br />

is also the home of the Schools of<br />

Sport, Exercise and Physical<br />

Education and Leisure and Sport<br />

Management, part of the Carnegie<br />

Faculty of Sport and Education.<br />

Staff of the school of Sport, Exercise<br />

and Physical Education work across<br />

the whole range of sport and<br />

exercise contexts that relate to the<br />

work of <strong>BASES</strong> and we look forward<br />

to providing an appropriate<br />

environment that will support<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> as it continues to develop<br />

and grow."<br />

Lactate<br />

Scout<br />

NEWS<br />

Headingley Campus at Leeds<br />

Metropolitan University<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> Annual Awards<br />

<strong>BASES</strong> members are encouraged to apply for the following awards:<br />

• <strong>BASES</strong> Awards for Good Practice in Applied Work - these awards are<br />

designed to recognise and reward examples of good practice and innovation<br />

in applied work. The application deadline is 29 April <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

• <strong>BASES</strong> Honorary Fellows Undergraduate Dissertation of the Year Award -<br />

this award is for the best abridged version of a <strong>2005</strong> UK final year<br />

undergraduate dissertation in the area of sport or exercise science. The<br />

application deadline is 30 September <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

• Philip Read Memorial Award for ‘Recently Qualified’ Researcher in Sport<br />

and Exercise Sciences - this award is for published research of outstanding<br />

merit in the field of sport or exercise sciences. The application deadline is 29<br />

April <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

■ www.bases.org.uk/newsite/awards.asp<br />

COURTESY OF PROF CARLTON COOKE<br />

The personal<br />

lactate analyser<br />

• Accurate results in 15 secs<br />

• Needs only 0.5µl of blood<br />

• Optimise endurance<br />

and fitness<br />

• Optional PC interface and<br />

analysis software<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

Lactate (mmol/l)<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

0<br />

basic level<br />

Amateur athletics<br />

Trained athletics<br />

Professionals<br />

3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5<br />

velocity (m/s)<br />

Achieve optimum training<br />

level under stress by<br />

measuring lactate level<br />

on the spot<br />

Buy on-line at<br />

www.sports-science.co.uk<br />

or call<br />

Vitech Scientific on<br />

01403 710479<br />

or fax to 01403 710382<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

7

EXERCISE SCIENCE<br />

Exercise Motivation and Adherence:<br />

The Use of Motivational Interviewing<br />

Jeff Breckon discusses this approach to behaviour change and highlights its benefits<br />

THIS paper summarises the theory and application<br />

of motivational interviewing (MI) and its potential<br />

as a counselling tool and intervention for exercise<br />

and physical activity specialists. One of the greatest<br />

challenges within exercise referral programmes,<br />

and the promotion of physical activity in a wider<br />

sense, is assisting clients and patients to initiate and<br />

maintain behaviour change. There is an increasingly<br />

unfit and sedentary population in the UK.<br />

In September 2004 the Secretary of State for Health suggested that<br />

while the population has an increasing awareness of the need to be<br />

physically active, the population in general does not have the<br />

motivation to initiate and maintain that behaviour change. The<br />

Health Development Agency (2004) recommends that<br />

interventions should use behavioural skills training, including selfefficacy,<br />

and emphasise risk reduction rather than promoting<br />

complete abstinence only. While many authors have offered<br />

guidelines as to ‘what’ an exercise counselling rubric should involve,<br />

few have offered the ‘how’ to action them. There is evidence that<br />

‘advice giving’ about lifestyle change is ineffective and in contrast that<br />

a more client-centred model produces better client responses.<br />

What has become increasingly apparent is the need for a method of<br />

counselling at all stages of exercise consultation that addresses the<br />

high drop-out rates from which many programmes suffer. It is<br />

therefore important to be able to train exercise specialists in a<br />

practical setting by explaining the fundamentals of exercise<br />

adherence and demonstrating the complex determinants of<br />

behaviour change. MI may then offer many health, exercise and<br />

physical activity professionals communication skills that assist the<br />

client to explore ambivalence and initiate that elusive behaviour<br />

change. Skills that are fundamental to MI, such as ‘reflective<br />

listening’, are difficult to teach but the style of the two-way<br />

relationship of MI helps to reduce client resistance and appreciates<br />

that the client is the expert of their own situation.<br />

What is Motivational Interviewing?<br />

Miller and Rollnick (1991, 2002) describe MI as a psychotherapeutic<br />

and evidence-based counselling technique that aims to help the<br />

client to explore and resolve his/her ambivalence to behaviour<br />

change. A number of detailed sources exist that describe the<br />

theoretical and philosophical underpinnings of MI<br />

(www.motivationalinterview.org). The Transtheoretical Model<br />

(Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) emerged at roughly the same<br />

time as MI and enables MI trainers to assist exercise and health<br />

specialists in understanding the processes that can enable a client to<br />

move away from risk behaviours, such as those seen in sedentary<br />

lifestyles.<br />

There are a number of 'tools' that can be used in MI clinical settings,<br />

one of which is the 'readiness ruler' (see Table 1). This provides an<br />

opportunity for the client to express his/her current readiness to<br />

change, based on his/her current motivation to initiate behaviour<br />

change and, just as importantly, his/her confidence in maintaining<br />

this change. More than one facet of behaviour can be mapped onto<br />

the readiness ruler. This supports the suggestion that risk behaviours<br />

are not mutually exclusive and that an inter-relationship between<br />

behaviours may often exist. For example, an exercise referral<br />

patient may be at pre-contemplation for their smoking, a<br />

contemplator for exercise and in the action stage when it comes to<br />

diet.<br />

Table 1. Readiness Ruler: Countdown Version<br />

(Miller & Rollnick, 2002)<br />

Not Ready Unsure Ready Trying<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

Pre-contemplation Contemplation Determination/Preparation Action<br />

Motivational Interviewing Phase I<br />

Motivational Interviewing Phase II<br />

When applying the readiness ruler a number of statements are used<br />

to elicit clients’ perception of their current ‘readiness for change’.<br />

For example, a non-exerciser might be asked, “On a scale of 1 to<br />

10, where would you put yourself?” The follow up question<br />

emphasises the positive element of the response where the client,<br />

depending on the result, would be asked (if for example they<br />

responded with a ‘5’) “Why 5 and not 2 or 1?” This results in<br />

primitive, but none-the-less effective 'self motivational statements'.<br />

The application of MI is aimed at increasing the likelihood of a client<br />

considering, initiating, and maintaining specific change strategies. This<br />

intervention strategy builds on the premise that change happens<br />

most effectively when the client generates it. This is a principle that<br />

is apparent in the use of reflective listening which clarifies and<br />

amplifies the client's own experience and meaning. These reflective<br />

listening strategies are applied in order to elicit client self-motivation,<br />

evidenced through change talk, as a consequence of exploring client<br />

ambivalence. An example in an exercise consultation would be a<br />

client who is encouraged to verbalise their reluctance or motivation<br />

for change as the exercise counsellor evokes and selectively<br />

reinforces the client’s own self-motivational statements whilst<br />

monitoring their readiness for change so as not to jump ahead of<br />

the client’s ‘stage’. By skilful reflective listening the exercise<br />

counsellor facilitates this change talk by the client.<br />

There are five general principles in MI, which assist counsellors in<br />

developing a ‘respectful’ method of moving a client through the<br />

stages of behaviour change. These are:<br />

• express empathy<br />

• develop discrepancy<br />

• avoid argumentation<br />

• roll with resistance<br />

• support self-efficacy.<br />

Clients who have self-efficacy have greater self-control and are<br />

therefore more likely to change for personal rather than external<br />

reasons. By increasing self-efficacy they are less likely to react to<br />

temptation and therefore maintain a health behaviour change.<br />

Fundamental to MI is its ‘spirit’ in application. Miller and Rollnick<br />

describe the ‘spirit’ that is commonly associated with MI and its<br />

principle of eliciting self-change through ‘negotiation’:<br />

1. Motivation to change is elicited from the client, and not<br />

imposed from others<br />

2. It is the client's task, not the counsellor's, to articulate and<br />

resolve his or her ambivalence<br />

3. Direct persuasion is not an effective method for resolving<br />

ambivalence<br />

8 <strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

www.bases.org.uk

EXERCISE SCIENCE<br />

4. The counselling style is generally a quiet<br />

and eliciting one<br />

5. The counsellor is directive in helping the<br />

client to examine and resolve ambivalence<br />

6. Readiness to change is not a client trait,<br />

but a fluctuating product of interpersonal<br />

interaction<br />

7. The therapeutic relationship is more like<br />

a partnership or companionship than<br />

that of expert/recipient.<br />

Part of the attraction of MI may exist in the<br />

practical application of techniques that can be<br />

delivered and trained without losing the<br />

essence of the MI approach. Miller describes<br />

this as:<br />

• Seeking to understand the person's frame<br />

of reference, particularly via reflective<br />

listening<br />

• Expressing acceptance and affirmation<br />

• Eliciting and selectively reinforcing the<br />

client's own self motivational statements,<br />

expressions of problem recognition,<br />

concern, desire and intention to change,<br />

and ability to change<br />

• Monitoring the client's degree of readiness<br />

to change, and ensuring that resistance is<br />

not generated by jumping ahead of the<br />

client.<br />

• Affirming the client's freedom of choice and<br />

self-direction.<br />

MI in varied settings<br />

To date, most of the clinical work and<br />

research employing MI has been associated<br />

with applied settings involving alcoholism,<br />

smoking, eating disorders, drug and substance<br />

abuse, and prison and probationary contexts.<br />

However, there is an increasing interest in its<br />

efficacy within lifestyle and behaviour change<br />

across a variety of health and primary care<br />

settings and indeed physical activity and<br />

exercise promotion. While there are<br />

numerous studies examining the application of<br />

‘stages of change’ to exercise settings with<br />

varied populations, there is still a paucity of<br />

empirical evidence testing the efficacy of<br />

applying MI techniques specifically in exercise<br />

and lifestyle change. A limited amount of<br />

research has been carried out in this setting<br />

and with equivocal findings. This could be a<br />

result of methodological inconsistencies, the<br />

depth of training of practitioners or indeed the<br />

client’s stage at which it is applied. The<br />

application of MI though is becoming<br />

widespread and is being rolled out by MI<br />

trainers to numerous physical activity, leisure<br />

services and exercise referral groups, as well<br />

as the British RAF. Research from Rollnick<br />

(1996) has vindicated the emergence of MI in<br />

the treatment of obesity and diet control by<br />

stating that, “It should be possible to<br />

encourage patients to be much more active in<br />

the consultation, and for practitioners to avoid<br />

some of the pitfalls of ineffective advice giving”<br />

(p.326). Most training that I now deliver is to<br />

physical activity coordinators and lifestyle<br />

consultants, which reflects the shift toward an<br />

appreciation of its potential in physical activity<br />

settings and the movement away from<br />

ineffective advice giving.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Miller & Rollnick (1991) suggest that MI is<br />

rarely dramatic, rather, “it is a particular way to<br />

help people recognize and do something<br />

about their present or potential problems” (p.<br />

52). So can MI help us to enable those<br />

sedentary members of the public to practise<br />

what we are trying to preach, but in a<br />

respectful and effective way? Learning skills in<br />

MI is similar in duration and difficulty to any<br />

other counselling and communication<br />

technique. While there are key skills delivered<br />

through MI training, the ‘spirit’ is an essential<br />

element and is only achieved by working with<br />

clients in an empathetic and respectful<br />

manner, appreciating clients’ autonomy and<br />

respecting their ambivalence to change. It is<br />

therefore a challenging technique to develop<br />

but holds substantial promise in exercise and<br />

physical activity settings. There is a need for<br />

further research into the effectiveness of MI in<br />

this context but what is clear is that the<br />

communication skill level in exercise specialists<br />

can improve significantly following training in<br />

MI. While in an embryonic stage with regards<br />

to this setting, MI’s application across so many<br />

other areas suggests that its fundamental<br />

principles may provide a new generation of<br />

health coaches, lifestyle consultants and<br />

physical activity officers with key skills and a<br />

style of delivery that is directive but in a far<br />

more client-centred manner. ■<br />

References<br />

Health Development Agency (2004). Evidence of<br />

effectiveness of public health interventions - and the<br />

implications (Choosing Health Briefing). www.hdaonline.org.uk/Documents/CHB1-public-health.pdf<br />

Miller, W.R. & Rollnick, S. (1991, 2002). Motivational<br />

Interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York:<br />

Guildford Press.<br />

Rollnick, S. (1996). Behaviour Change in Practice:<br />

Targeting Individuals. International Journal of Obesity, 23,<br />

325-334.<br />

www.motivationalinterview.org<br />

In the next issue of The Sport and Exercise<br />

Scientist there will be an example of MI use.<br />

Jeff Breckon<br />

Jeff is a senior lecturer in<br />

exercise psychology at Sheffield<br />

Hallam University and a member<br />

of the Motivational Interviewing<br />

Network of Trainers and <strong>BASES</strong>.<br />

His clinical, research and<br />

teaching interests are in exercise<br />

motivation and adherence.<br />

Osmocheck<br />

The new personal<br />

“Osmometer”<br />

for monitoring<br />

dehydration<br />

• Instant results<br />

• Needs only a drop<br />

of urine<br />

• Easy to keep clean<br />

Osmocheck is a refractometer<br />

calibrated from<br />

0-1500mOsmol/kgH20 and<br />

gives an immediate indication<br />

of the onset of de-hydration.<br />

mOsmol/kgH20<br />

1500<br />

danger<br />

1000<br />

warning<br />

600<br />

good<br />

200<br />

The relationship<br />

between<br />

refractive index<br />

and osmolality is<br />

empirical and<br />

Osmocheck<br />

results should<br />

always be<br />

benchmarked<br />

against a<br />

Laboratory based<br />

Freezing Point<br />

Osmometer,<br />

such as the<br />

Advanced Micro<br />

Osmometer.<br />

Buy on-line at<br />

www.sports-science.co.uk<br />

or call<br />

Vitech Scientific on<br />

01403 710479<br />

or fax to 01403 710382<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

9

EDUCATION<br />

Making Research Methods more ‘attractive’<br />

to sport and exercise science students<br />

Dr Clare Hencken discusses some of her experiences of designing and teaching research methods courses<br />

Making ‘Research Methods’ appealing<br />

is quite a challenge. Many sport and<br />

exercise scientists cringe at the<br />

mention of statistics and even more so<br />

when words like ‘ethics’ are banded<br />

about. This is not to say that ethical<br />

and statistical procedures are not<br />

followed; rather, that such procedures<br />

are the decidedly unglamorous<br />

elements of the research game. As a<br />

research coordinator for “Research<br />

Methods” to second year<br />

undergraduate sport science students<br />

and “Research Applications in Sport<br />

Science” to MSc students, I aim to<br />

make such aspects of sport and<br />

exercise science attractive and<br />

enjoyable.<br />

“We all recognise the<br />

importance of research<br />

methods and it is a<br />

universal requirement”<br />

Research methods is often described,<br />

at best, as “dry” and, at worst, “dull<br />

and boring”, and it is reframing these<br />

perceptions that is the challenge for<br />

the sport science lecturer. Many of us<br />

are, by the very nature of our subject<br />

area, competitive and yet the research<br />

methods gauntlet has been thrown<br />

down, and many of us are reluctant to<br />

take it up.<br />

We all recognise the importance of<br />

research methods and it is a universal<br />

requirement that we include within our<br />

syllabuses. But, as it is historically<br />

unpopular with the students, few<br />

volunteer to teach it! As I see it, the<br />

delivery of research methods presents<br />

two central challenges:<br />

• to ‘win’ the students over, and<br />

• to increase the confidence of sport<br />

and exercise science lecturers who<br />

teach research methods units.<br />

To ‘win’ the students over<br />

A number of initiatives can be actioned:<br />

1. Every example used to demonstrate<br />

the application of research principles<br />

should have links to the sport and<br />

exercise curriculum. This linkage is<br />

complicated by the multidisciplinary<br />

nature of sport and exercise science.<br />

In addition, research methods modules<br />

are typically delivered to a combination<br />

of sport studies students, sport<br />

development students, and sport and<br />

exercise science students. Banks of<br />

examples and scenarios are required<br />

to gain, and maintain, the interest of<br />

these cohorts, and actually address<br />

questions that they might face within<br />

their particular area of study. This can<br />

be achieved by engaging the other<br />

members of the sport and exercise<br />

science team and discussing typical<br />

research problems faced by, for<br />

example, the psychologists, the<br />

biomechanists, the physiologists, the<br />

sport developers or the sports<br />

managers within the department.<br />

2. The timing and length of the<br />

research methods unit within an<br />

undergraduate programme is crucial. If<br />

it is too early in their academic career,<br />

students cannot fully appreciate the<br />

application of research, and simply ‘go<br />

through the motions’. By the time they<br />

are provided with opportunities to<br />

apply research principles, they are<br />

usually unable to recall the processes<br />

involved. If it is too short a unit (1<br />

semester), there is so much to learn<br />

that the students often feel overawed<br />

by the topic, and they end up<br />

resenting the time it takes to learn how<br />

to produce an ethically viable<br />

experimental design, or to use<br />

computer software such as SPSS to<br />

interpret data, when other, perhaps<br />

more pressing, assessment deadlines<br />

are approaching.<br />

3. The assessments within the<br />

‘Research Methods’ unit must<br />

contribute to the attainment of learning<br />

objectives and outcomes for the<br />

degree programme. For example,<br />

incorporating the development of a<br />

research proposal and protocol prior to<br />

their final year. This would help the<br />

students to understand better a<br />

process vital to their final year<br />

project/dissertation. Additionally, since<br />

the unit is teaching ‘methodology’,<br />

assessments should be graded using<br />

the full scale of marks from 0-100%, so<br />

that mastery is promoted and<br />

encouraged.<br />

4. The notion of research and data<br />

analysis needs to be embraced by the<br />

entire sport and exercise science<br />

department so that other cognate<br />

areas and units utilise the skills learnt<br />

in research methods elements. This<br />

may help to elevate research methods<br />

in terms of importance to the students,<br />

and also encourages students to get<br />

to grips with the various considerations<br />

associated with research design,<br />

sampling, methods of data collection<br />

and interpretation, and triangulation<br />

because they are also rewarded in<br />

other unit assessments for transferring<br />

knowledge and skills across units. This<br />

is something that we all aspire to when<br />

planning our curriculum, and yet we<br />

need to ensure that the mechanisms to<br />

execute such a plan are put in place<br />

within each department.<br />

Increasing confidence of sport and<br />

exercise science lecturers teaching<br />

research methods.<br />

The notion of research<br />

and data analysis needs<br />

to be embraced by the<br />

entire sport and exercise<br />

science department<br />

We need to consider the following:<br />

1. A great deal of the success<br />

achieved with regard to the teaching of<br />

research methods in my own<br />

department can be attributed to the<br />

support that other members of staff<br />

give to the Research Methods<br />

Coordinator. Like many other sport and<br />

exercise science departments, student<br />

reviews concerning the research<br />

methods module used to be negative.<br />

Students described the module as<br />

‘boring’, ‘not applicable’ and ‘hard to<br />

get their heads around’. Recognising<br />

the need for change, the Head of<br />

Department was flexible, allowing the<br />

curriculum to be manipulated so that<br />

research methods could be<br />

restructured into a year-long, doublesemester,<br />

double-credit unit.<br />

2. It is beneficial to make use of other<br />

staff members’ input, e.g., I was<br />

actively encouraged to write a<br />

‘Research and Statistics Manual’ for<br />

staff and students providing flowcharts<br />

and step-by-step guidelines to<br />

walk someone through the research<br />

process, ethical submissions and<br />

statistical analyses. Staff development<br />

workshops were, and still are,<br />

timetabled within the academic year so<br />

that the area of research methods is<br />

10 <strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

www.bases.org.uk

EDUCATION<br />

not seen as a one-person crusade,<br />

and so other staff can offer statistical<br />

support to students and other<br />

members of the department. It also<br />

seems that the team approach is a<br />

sure way to emphasise the<br />

importance of research methods in<br />

the eyes of the students.<br />

3. Many students’ concerns about<br />

research methods related to the lack<br />

of appropriate reading material, and I<br />

have to say I agree. The interpretation<br />

of the term ‘appropriate’ appears to<br />

refer to the fact that many of the<br />

research texts are written in an<br />

antiquated format with long flowery<br />

words, complex technical jargon and<br />

an assumption that the reader knows<br />

something about what they are doing!<br />

These texts are very useful to<br />

experienced researchers but to the<br />

novice, they are far from ‘appropriate’.<br />

4. This leads to another controversial<br />

point: should we get down to grassroots<br />

and teach our students to<br />

undertake complex mathematical data<br />

analysis by hand (as I was taught), or<br />

should we teach them which buttons<br />

to press in a data analysis software<br />

programme, such as SPSS? This is a<br />

debate that could cause division but I<br />

will provide my opinion on this matter.<br />

Many would argue that mathematics<br />

is probably even less ‘alluring’ than<br />

research methods. So, if you insist<br />

that sport and exercise science<br />

students develop their mathematical<br />

skill to a point that they can easily<br />

undertake a repeated measures<br />

ANOVA, or indeed a regression<br />

analysis, by hand, you are most<br />

certainly going to alienate most of<br />

your students.<br />

Is it not, therefore, a better idea to<br />

teach them the purpose of the<br />

analysis, i.e., exactly what the analysis<br />

is doing, and then ‘turn them on’ by<br />

switching on a computer and<br />

explaining that it will do the hard bit<br />

for them? From my humble<br />

perspective, it is this that excites the<br />

students; as they come to terms with<br />

analysis and experimental design.<br />

Their challenge then is to learn how to<br />

run a programme and then interpret<br />

the data within the context of the<br />

research question.<br />

I do not believe that this is ‘dumbing<br />

down’ the academic quality of<br />

research methods, as there is still a<br />

high degree of aptitude required to<br />

load data appropriately, determine<br />

which analysis to undertake, correctly<br />

decipher the output, and finally relate<br />

it back to the scenario under<br />

investigation.<br />

Conclusion<br />

With the renewed encouragement I<br />

have had from recent student<br />

feedback, I feel I have been<br />

successful in making research<br />

methods of interest to the sport and<br />

exercise science students simply by<br />

following the above principles. It has<br />

taken years of trial and error to achieve<br />

this but now the undergraduate unit<br />

involves a mixture of lectures,<br />

workshops and assessments, where<br />

students apply the research skills they<br />

have learnt. This system is not only<br />

confined to quantitative data; they also<br />

watch videos and use qualitative<br />

methods to analyse what they observe,<br />

they create vignettes and mock<br />

interviews that require transcription,<br />

and they examine questionnaires/<br />

surveys and single-subject designs.<br />

Yet still the first rule applies - at all<br />

times the bank of examples is geared<br />

to many aspects of sport and exercise<br />

so that all cohorts are engaged. There<br />

is also a natural progression within the<br />

undergraduate and postgraduate<br />

research methods. The postgraduate<br />

modules are more complex and<br />

applied, incorporating exercises that<br />

require the students to prepare work<br />

ready for journal submission, as this<br />

can be a particularly onerous task and<br />

one that requires some practice.<br />

I think the single most satisfying<br />

element of teaching research methods<br />

is when students gain the confidence<br />

to ‘have a go’. I now have students<br />

eagerly requesting new data sets to<br />

analyse and interpret, as they become<br />

increasingly aware that research<br />

designs and associated analysis can<br />

develop our understanding of complex<br />

and applied events in sport. ■<br />

Further reading<br />

Lane, A. M., Devonport, T. J. & Horrell, A.<br />

(2004). Self-efficacy and research methods. Journal<br />

of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education.<br />

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. & Daley, C. E. (1996). The<br />

relative contributions of examination-taking coping<br />

strategies and study coping strategies to test anxiety:<br />

a concurrent analysis. Cognitive Therapy and<br />

Research, 20, 287–303.<br />

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. & DaRos-Voseles, D. A.<br />

(2001). The role of cooperative learning in research<br />

methodology courses: A mixed-methods analysis.<br />

Research in the Schools, 8, 61–75.<br />

Dr Clare Hencken<br />

Clare is a Senior Lecturer in<br />

the Department of Sport &<br />

Exercise Science at the<br />

University of Portsmouth. She<br />

teaches Research Methods<br />

and Statistics to both<br />

undergraduate and<br />

postgraduate students.<br />

Quick check<br />

for<br />

dehydration<br />

Urine Osmolality is recognised<br />

to be ‘The Gold Standard’ for<br />

dehydration monitoring and is<br />

used routinely by Sports<br />

Physiologists during training and<br />

competitions.<br />

The Advanced Micro<br />

Osmometer has been shown to<br />

be quick, reliable and<br />

reproducible and sufficiently<br />

rugged to withstand the rigours<br />

of use away from the laboratory.<br />

If you want to keep up with<br />

Boxing, Canoeing, Cycling,<br />

Football, Gymnastics, Hockey,<br />

Netball, Rowing, Rugby, Sailing,<br />

Swimming, The Olympic<br />

Medical Institute and Sports<br />

Science departments throughout<br />

the UK contact:<br />

Vitech Scientific Ltd<br />

Huffwood Trading Estate<br />

Partridge Green<br />

West Sussex RH13 8AU<br />

Buy on-line at<br />

www.sports-science.co.uk<br />

or call<br />

Vitech Scientific on<br />

01403 710479<br />

or fax to 01403 710382<br />

E mail: sales@vitech.co.uk<br />

www.bases.org.uk<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist 11

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE<br />

Changing athletes’ behaviour: Lessons learnt<br />

Dr Claire Palmer reflects on her own professional practices in applied<br />

sports science to highlight some key lessons she has learned along the way<br />

Introduction<br />

In my opinion, Claire’s reflections are of relevance to all sport and exercise scientists who are in the business of trying to<br />

change other people’s behaviours. The work that Phil Moore, Dave Wilkinson and I did for the <strong>BASES</strong>/Sports Council<br />

Interdisciplinary Review in 1992 revealed that adherence to any form of training or intervention was one of the five most<br />

important problems for all sports. The findings of a follow-up survey published in the <strong>BASES</strong> Newsletter in 1999<br />

confirmed this view. As an interdisciplinary issue, you would have thought that it was of real importance for<br />

physiologists, biomechanists, sport psychologists and performance analysts. However, the evidence is that the<br />

participants in the <strong>BASES</strong> Adherence to Training workshops since 2003 have been predominantly from sport<br />

psychology, with only 20% coming from any of the other disciplines. It does seem to me, however, that adherence is<br />

relevant across the sports science board. ■ Prof Les Burwitz<br />

THIS article aims to pick out some of the key<br />

lessons that I’ve learned from 10 years of<br />

applied work as a sports scientist. My research<br />

and applied focus relates to adherence issues.<br />

On a practical level, there is little value in<br />

prescribing programmes if athletes are either<br />

unable or unwilling to adopt and maintain any<br />

recommendations made. For me, a number of<br />

questions arose concerning the problem of<br />

adherence: what factors influence adherence<br />

and can intervention strategies be successfully<br />

used to increase adherence? Through research<br />

with sports groups, I have attempted to answer<br />

some of these questions and interested parties<br />

are directed to read Palmer et al. (1999; 2000).<br />

Rather than repeat those findings in this article,<br />

I have sought to take advantage of the<br />

potentially unique forum that The SES provides<br />

by sharing reflections on some key events that<br />

have significantly influenced my work practice<br />

– the issue of training adherence is merely<br />

used as the vehicle through which those<br />

lessons were learned.<br />

Across a time period of 10 years inevitably<br />

there have been changes to the way elite<br />

performers are supported. For example, Lottery<br />

funding has become available, enabling the<br />

UK's top sportsmen and women to access a<br />

package of scientific support through their<br />

respective sports. The World Class<br />

Performance Programme is designed to<br />

develop athletes and provide them with all the<br />

necessary elements to perform. This has<br />

undoubtedly assisted with adherence issues for<br />

this elite sport community. However, sport and<br />

exercise scientists, involved with team-sport<br />

athletes unable to access such individualised<br />

support and performing most training in<br />

unsupervised settings, continue to report<br />

issues with training adherence.<br />

1. In “my universe” I’m the norm<br />

In 1992, a close friend was selected to<br />

compete in a team sport at a World Youth Cup.<br />

Whilst juggling summer vacation jobs, we both<br />

religiously followed the fitness training set for<br />

the squad by the team’s sport physiologist. We<br />

both genuinely enjoyed the training and were<br />

even happy doing plyometrics in front of<br />

bemused ground staff. However, although my<br />

Agree the role of testing<br />

friend trained hard, she often complained about<br />

teammates who were not completing the<br />

recommended training.<br />

My experiences with adherence problems came<br />

closer to hand when I started working with a<br />

team sport on a Sports Science Support<br />

Programme and started a PhD looking at<br />

adherence. Other sport and exercise scientists<br />

and I were surprised at a general lack of fitness<br />

among the athletes relative to our expectations.<br />

Moreover, despite the provision of training<br />

programmes, some athletes appeared to not<br />

improve across seasons and this was often<br />

associated with half-filled training diaries.<br />

I, like many sport scientists that I talk to, are<br />

the types of individuals that wouldn’t dream of<br />

not following a programme. But whilst in “our<br />

universe” we are the norm, to be effective<br />

practitioners it is important not to assume that<br />

our values and beliefs are representative of our<br />

clients. As part of the preliminary needs<br />

analysis with the client, an understanding of<br />

the athletic context in which the athletes<br />

operate should be gained (e.g., assess the<br />

athletes’, the coach’s and the sporting<br />

organisation’s knowledge of and commitment<br />

to fitness or indeed any other aspect of<br />

training). This assessment can involve asking<br />

questions about previous training histories and<br />

looking at what normally happens at the level<br />

below. If the training that you aim to introduce<br />

is not integral at the level that the athlete has<br />

just progressed from, then the behaviour will<br />

probably not be habitual and its adoption may<br />

require a dramatic lifestyle change. Such an<br />

assessment will allow the practitioner to<br />

establish whether his or her expectations<br />

regarding training prescriptions are realistic and<br />

what support is required. I think this is<br />

particularly relevant for probationary sport and<br />

exercise scientists who are typically<br />

enthusiastic in their own training to become<br />

accredited and may make the mistake of<br />

assuming this enthusiasm exists in whoever<br />

they are working with.<br />

2. This applies to everyone but me<br />

Aware of the adherence issues within the squad<br />

in which I worked, I ran a group workshop<br />

aimed at improving adherence. I thought the<br />

session went well until an hour later I bumped<br />

into one of the athletes, whom I considered to<br />

be a low-adherer, and asked her what she<br />

thought of the session. She responded, “It was<br />

good, cos the whole squad’s really fed up with<br />

Nicky (not her real name) not training and it’s<br />

good that that’s been highlighted.” I left in<br />

silence because clearly this athlete (and I<br />

feared most of the squad) had sat throughout<br />

the whole session thinking the message was<br />

aimed at only one athlete. How could an<br />

athlete who regularly handed me a half-empty<br />

training diary and under-performed in fitness<br />

monitoring regard herself as a trainer? Surely<br />

the relevancy of the workshop’s messages to<br />

her would be clear? Obviously not and I had<br />

DR CLAIRE PALMER<br />

12<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 3 <strong>March</strong> <strong>2005</strong> The Sport and Exercise Scientist<br />

www.bases.org.uk

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE<br />

made the mistake of assuming otherwise.<br />

I now consider intervention checks, formal<br />

and/or informal, as critical to evaluating my<br />

effectiveness. These checks range from formal<br />

paper-based evaluation forms completed<br />

anonymously by both athletes and support staff<br />

to an informal question such as, “What did you<br />

think of that session?” As rapport and trust<br />

builds up, I found individuals to be fairly<br />

honest in their appraisals.<br />

Additionally, as a result of my initial ‘waste-oftime’<br />

group adherence workshop session I<br />

decided in future to run group sessions only if I<br />

considered it to be the most appropriate<br />

intervention format. My view is that it’s difficult<br />

to be effective if you can’t work on an<br />

individual basis. Early in my career I would take<br />

whatever sessions were made available, keen<br />

for whatever experiences I could get. But I<br />

wouldn’t run a session unless a coach was<br />

prepared to allow adequate time and priority for<br />

me to do a job properly. All too often I notice<br />

that sport science workshops are timetabled<br />

late in the evening when athletes would rather<br />

rest and recover. By continually agreeing to<br />

work the ‘graveyard slot’ I think the role of<br />

sport science in positively impacting on<br />

performance is in danger of being devalued. I<br />

think the important thing is to not always agree<br />

straight away to running a session, particularly<br />

if you think the timing is not ideal. This does<br />

not mean being unaccommodating but in my<br />

experience, by challenging the timetable and<br />

requesting more time I actually gained<br />

credibility.<br />

3. You won’t know you have a problem<br />

unless you look<br />

I soon learned that the prescription of a training<br />

programme does not ensure the adoption and<br />

maintenance of the target behaviours, even in<br />

high-level sport groups where motivation is<br />

often assumed to be high. Provision of a fitness<br />