OAS Journal - University of Oklahoma

OAS Journal - University of Oklahoma

OAS Journal - University of Oklahoma

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

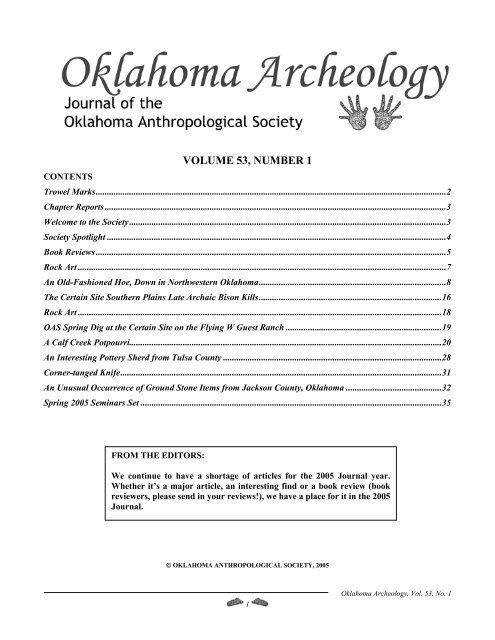

VOLUME 53, NUMBER 1<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Trowel Marks.............................................................................................................................................................2<br />

Chapter Reports .........................................................................................................................................................3<br />

Welcome to the Society..............................................................................................................................................3<br />

Society Spotlight ........................................................................................................................................................4<br />

Book Reviews .............................................................................................................................................................5<br />

Rock Art .....................................................................................................................................................................7<br />

An Old-Fashioned Hoe, Down in Northwestern <strong>Oklahoma</strong>....................................................................................8<br />

The Certain Site Southern Plains Late Archaic Bison Kills..................................................................................16<br />

Rock Art ...................................................................................................................................................................18<br />

<strong>OAS</strong> Spring Dig at the Certain Site on the Flying W Guest Ranch ......................................................................19<br />

A Calf Creek Potpourri............................................................................................................................................20<br />

An Interesting Pottery Sherd from Tulsa County ..................................................................................................28<br />

Corner-tanged Knife................................................................................................................................................31<br />

An Unusual Occurrence <strong>of</strong> Ground Stone Items from Jackson County, <strong>Oklahoma</strong> ...........................................32<br />

Spring 2005 Seminars Set .......................................................................................................................................35<br />

FROM THE EDITORS:<br />

We continue to have a shortage <strong>of</strong> articles for the 2005 <strong>Journal</strong> year.<br />

Whether it’s a major article, an interesting find or a book review (book<br />

reviewers, please send in your reviews!), we have a place for it in the 2005<br />

<strong>Journal</strong>.<br />

© OKLAHOMA ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 2005<br />

1<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Trowel Marks<br />

Hello Everyone,<br />

I hope you all had a wonderful Christmas and enjoyed<br />

the holidays. Winter is <strong>of</strong>ficially here now--time to<br />

stay indoors and dream and plan for sunny spring days<br />

and outdoor activities. Committees have been very<br />

busy planning our Spring Conference, Spring Dig, the<br />

Caddo Conference, <strong>Journal</strong> articles, certification<br />

seminars, perhaps even a Fall Dig.<br />

We had an excellent and informative January board<br />

meeting. Lois Albert mentioned there will be several<br />

certification seminars <strong>of</strong>fered throughout this spring<br />

and during the dig. So watch for the dates if you are<br />

needing any <strong>of</strong> these seminars.<br />

The Caddo Conference will be March 17-19 at the<br />

Sam Noble Museum. Papers will be presented on<br />

Thursday and Friday, then on Saturday, the 19th, the<br />

Caddos will have a Powwow dance. Lois Albert is<br />

getting them all set up.<br />

Our <strong>OAS</strong> Spring Conference is Friday, May 6, and<br />

Saturday, May 7, at the Sam Noble Museum. Friday<br />

night is the social time with Don Wyck<strong>of</strong>f's band<br />

playing "Music under the Mammoth." Saturday is the<br />

board meeting, morning speakers, then in the<br />

afternoon we will have our panel <strong>of</strong> speakers<br />

discussing Critical Issues in Archaeology in<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong>, with an open discussion afterwards. Our<br />

speakers for the panel will be Pat Gilman, Lewis<br />

Vogele, Robert Brooks, Charles Wallis, Meeks<br />

Etchieson, Bob Blasing, John Hartley, Stephen<br />

Perkins, and KC Kraft. Saturday night is the banquet<br />

dinner, awards, and another guest speaker. I am still<br />

working on the fine details and will let you know<br />

more in the next issue <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Journal</strong> which will come<br />

out before our meeting. But it should be an interesting<br />

and thought provoking conference, and hopefully a lot<br />

<strong>of</strong> issues can be brought out into the open for<br />

discussion and some problems made aware <strong>of</strong>/or<br />

solved.<br />

The Spring Dig will be the Certain Site which is<br />

located 5 miles from Elk City. The dates are May 21-<br />

30. This is a late archaic bison kill site. The site is on<br />

the Flying W Dude Ranch and will have camping<br />

facilities. There is plenty <strong>of</strong> room and also a large<br />

dining hall for gatherings and seminars. Lee Bement<br />

is the archaeologist in charge and says that at this<br />

extensive site several hundred bison skeletons and<br />

many points have been found. More information will<br />

come later, but mark your calendar for these dates.<br />

On the east side <strong>of</strong> Lake Keystone is an area that is<br />

badly eroded and needs attention, as much has already<br />

been found there. But this may be a Fall Dig in the<br />

making.<br />

KC Kraft had a group meet at the Survey Department<br />

to clean up the big trailer, take inventory and repair<br />

equipment. Thanks to all who helped with this.<br />

The Fall Meeting will be at OSU. I will be making a<br />

few trips to Stillwater this summer to work on plans<br />

for the program with Dr. Stephen Perkins. I don't<br />

have any dates as yet. Dr. Perkins spoke about the<br />

Aztec Culture at our Central Chapter one night, so I<br />

know we can make this an interesting day.<br />

Pat Gilman told us that George Bass, who is the father<br />

<strong>of</strong> nautical archaeology, will be speaking March 3-4.<br />

And two visiting Chinese archaeologists will be<br />

speaking sometime in February on their work on the<br />

clay warriors.<br />

Diane Denton has come up with a project idea to<br />

bring in some money for the society. This is a bison<br />

skull necklace charm or pin with a red zigzag in either<br />

silver or gold. Lee Bement said he didn't see any<br />

problems with getting this set up. And this is<br />

exclusively <strong>Oklahoma</strong>n!!!!!<br />

Archaeology Day is also still an idea for next fall. We<br />

think hands on things, outdoor activities, helpful<br />

archaeologists, and lots <strong>of</strong> information will bring in<br />

families....and new members.<br />

The downside news is that membership is down, and<br />

we need articles for the <strong>Journal</strong>.<br />

<strong>OAS</strong> has many exciting things planned for this year. I<br />

hope that with some good publicity, we can entice<br />

many who have wandered away to come back and<br />

reconnect with us, and that we can also get new<br />

individuals interested enough to join us.<br />

Kathy Gibbs, President<br />

2<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Chapter Reports<br />

Byrds Mill (Ada) Chapter<br />

They meet the 2nd Tuesday <strong>of</strong> each month with the<br />

exception <strong>of</strong> June, July, and August. They had a<br />

really good attendance for the November meeting.<br />

They have added one new member. They have good<br />

meetings planned through May, including a field trip<br />

planned to see cave art.<br />

Carl Gilley says that he is willing to go to McAlester<br />

and help them get set up again. He says there are<br />

some interested people there, and he will try to get it<br />

going.<br />

Report filed by Carl Gilley<br />

Tulsa Chapter<br />

The Tulsa chapter meets on the 4th Monday at 7 pm.<br />

at the Aaronson auditorium, downtown public library.<br />

Our Jan. 24th program was, The Osage, speaker<br />

Leonard Maker. On Feb 28th, our speaker will be<br />

Bryan Tapp, Ph.D. geologist, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Tulsa. He<br />

will speak on the evolution <strong>of</strong> the Ouachita<br />

Mountains. Our March 28th speaker is Carol Eames.<br />

Her program is Walking South New Zealand. Carol is<br />

a retired Tulsa zoo educational curator. Our chapter<br />

president, Bill Obrien is going to speak to the Mayes<br />

County genealogical society Monday March the l4th<br />

in Pryor. His program is about the Texas road that<br />

passed between Pryor and Grand Lake.<br />

For an entertaining and enjoyable dinner come join us<br />

at Baxter Interurban, 727 S. Houston, about 5:00 p.m.<br />

before our monthly meeting. You may have the<br />

opportunity to meet our presenter and the conversation<br />

is never boring! Come see for yourself!<br />

Report filed by Charles Surber<br />

Central Chapter<br />

The <strong>Oklahoma</strong> City chapter <strong>of</strong> O.A.S. meets on the<br />

first Thursday <strong>of</strong> each month from 7 to 9 p.m. at the<br />

Garden Center in Will Rogers Park (on the southwest<br />

corner <strong>of</strong> N.W. 36 and I-44).<br />

The December meeting was a potluck dinner and<br />

“dirty Santa” gift exchange at the Staneks’ home.<br />

January’s meeting was cancelled because <strong>of</strong> ice.<br />

The March program (rescheduled from January) will<br />

be Dr. Fred Schneider, a retired anthropology<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essor, who will discuss how corn cultivation by<br />

Native Americans spread rapidly northward in what is<br />

now the U.S.<br />

Report filed by Charles Cheatham<br />

Welcome to the Society<br />

New Members, 12/01/2004 through 02/01/2005<br />

Contributing<br />

Chester L. Shaw, Sheridan, AR<br />

Dovie Warren, Granite<br />

Active<br />

Katherine Dickey, Weatherford<br />

Nicholas Johnson, Norman<br />

Lance L. Larey, Tulsa<br />

Billy Bob Ross, Ada<br />

Stewart J. Smith, OKC<br />

Alexander C. Ward, OKC<br />

Kay Weast, Weatherford<br />

3<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Society Spotlight<br />

Leland C. Bement<br />

Born in Texas during the fifth decade <strong>of</strong> the last<br />

century, I grew up in South Dakota along the Missouri<br />

River. Family outings along the river led to a lifetime<br />

infatuation with prehistoric cultures. Pot sherds make<br />

great skipping stones. After graduating from High<br />

School in El Salvador, I spent the summer<br />

volunteering at a late classic Maya site. My<br />

undergraduate career was accomplished at Fort Lewis<br />

College in Durango, Colorado. From there we (I<br />

picked up a wife and daughter along the way) moved<br />

to Austin, Texas so that I could continue my<br />

education. I received an MA and PhD from the<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Texas at Austin. Accompanying my<br />

graduate classes, I worked full time at the Texas<br />

Archaeological Survey (Later called TARL-SP) which<br />

provided a wide variety <strong>of</strong> experience in contract and<br />

research archaeology. My MA thesis included the<br />

Pleistocene animal remains from Bonfire Shelter in<br />

SW Texas. My PhD dissertation was the analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

the human, animal, and artifactual remains from<br />

Bering sinkhole (also in Texas). These sites<br />

awakened an interest in animal bone analysis which<br />

continues today. Oh yes, Jason came along during<br />

that time. Upon completion <strong>of</strong> my PhD I searched for<br />

the perfect job. After turning down <strong>of</strong>fers from<br />

prestigious contract firms I accepted a position with<br />

the <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeological Survey. I have just<br />

completed 13 years with the <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeological<br />

Survey—the longest I’ve stayed anywhere in my life.<br />

When UT plays OU at the Cotton Bowl, my team<br />

always wins!<br />

Favorite Food: Buffalo<br />

Favorite Animal: Buffalo<br />

Best Discovery: My wife, Terry, (and a painted bison<br />

skull)<br />

Favorite Activity: Do you need to ask?<br />

Hobby: Hunting with Jason.<br />

4<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Sign: Sagittarius<br />

Favorite Color: Blue<br />

Favorite Car: 1951 Chevy pickup<br />

Current Research: I am actively involved in the<br />

excavation and analysis <strong>of</strong> Paleoindian sites in<br />

western <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. Sites <strong>of</strong> particular note are Cooper<br />

and Jake Bluff. Other research interests include<br />

faunal analysis, bison kill sites, hunter-gatherer<br />

studies, and paleo-environmental reconstructions<br />

Book Reviews<br />

The Long Summer: How Climate Changed<br />

Civilization by Brian Fagan (Published by Basic<br />

Books, 2004, 284 pages, $26, ISBN: 0465022812).<br />

Reviewed by Jon Denton<br />

Brian Fagan is an archeologist known to value the<br />

effect <strong>of</strong> climate on history. He does not give in easily<br />

to alarm. That's what makes the last page <strong>of</strong> his latest<br />

book scary stuff.<br />

No doubt climate has had a great impact on human<br />

history. Humans have become adept at adaptation. Yet<br />

great societies have risen and fallen in response to the<br />

capricious pendulum <strong>of</strong> weather. Despite their selfproclaimed<br />

certainty <strong>of</strong> power, the story <strong>of</strong> many<br />

civilizations is written in the dust, says Fagan, an<br />

emeritus anthropologist at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

California, Santa Barbara.<br />

"The collapses <strong>of</strong>ten came as a complete surprise to<br />

rulers and elites who believed in royal infallibility and<br />

espoused rigid ideologies <strong>of</strong> power. There is no reason<br />

to assume that we've somehow escaped this shaping<br />

process," he tells us.<br />

"The Long Summer" uses archeology to demonstrate<br />

how it happens. Most <strong>of</strong> mankind's history occurred<br />

during the last 15,000 years, the Holocene. As<br />

temperatures rose, glaciers receded and sea levels<br />

climbed. Human civilization responded to the long<br />

summer with technology, population growth and<br />

government.<br />

As he did in his previous two books linking weather<br />

and climate to human history -- "Floods, Famines, and<br />

Emperors" and "The Little Ice Age" -- Fagan shows us<br />

how climate influences us in positive and negative<br />

ways. He focuses on the rise <strong>of</strong> civilizations in what<br />

are now the Middle East, Europe and the Americas.<br />

A gradually warming earth led to a cattle herding<br />

culture among ancient Egyptians. Rising sea levels<br />

created the Persian Gulf and Fertile Crescent, which<br />

generated the rise <strong>of</strong> Mesopotamia.<br />

Not that all was wet and warm. Humans invented<br />

agricultural techniques in response to colder weather.<br />

That led them to build permanent cities and<br />

communities, follow rulers, devise governments,<br />

assemble armies and declare warfare.<br />

Sometimes it was simply warm or cold, with little<br />

moisture. Droughts in the Middle East spurred the<br />

deliberate cultivation <strong>of</strong> plant foods. A thousand-year<br />

chill, caused by a sudden shutdown <strong>of</strong> the Gulf<br />

Stream, led to the rise <strong>of</strong> a reindeer culture.<br />

The Vikings, suddenly frozen out <strong>of</strong> their excursions<br />

south to Europe and West to America, left discovery<br />

<strong>of</strong> much <strong>of</strong> the New World to the Spanish, Portuguese,<br />

English and French.<br />

Today the world is crowded with humans. Millions<br />

depend on a productive few for food and water. A<br />

sudden shift in climate could threaten a civilization<br />

that has become top heavy.<br />

That is the message Fagan's book makes clear. His<br />

book is an important and highly readable account <strong>of</strong><br />

history, measured not by time but climate. It is<br />

recommended for anybody concerned about global<br />

warmth.<br />

Bison Hunting at Cooper Site<br />

Where Lightning Bolts Drew Thundering Herds<br />

By Leland C. Bement with a contribution by Brian J.<br />

Carter (Published by <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Press,<br />

1999, 256 pages, $19.95, ISBN: 0-8061-3053-9)<br />

Reviewed by Seth Hawkins<br />

On the far horizon, a brilliant orange-sun- drifts<br />

slowly below the rim <strong>of</strong> the earth. Beams <strong>of</strong> yellow<br />

5<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

pierce the billowing white clouds as they grow ever<br />

larger and darker, an ominous portent <strong>of</strong> a gathering<br />

storm. To the south and west dark curtains <strong>of</strong> rain fall<br />

as jagged shafts <strong>of</strong> light split the western sky. Over the<br />

gently rolling, red sandstone hills, a carpet <strong>of</strong> lush<br />

grasses waves silently in the s<strong>of</strong>t, cool breeze <strong>of</strong> the<br />

advancing twilight. The pungent "sage scent" <strong>of</strong> the<br />

prairie brushes over the landscape as the nighthawk<br />

dips and turns, winging its way through the darkening<br />

valley below. Slicing the broken divides, a sluggish,<br />

meandering river intrepidly makes its way to the south<br />

and east, twisting and tuning at the slightest<br />

obstruction, its murky waters carrying a heavy load <strong>of</strong><br />

tawny brown silt from the high plains and the far<br />

distant mountains beyond. The last golden rays <strong>of</strong><br />

sunlight peek over the distant western hills, reflecting<br />

a deep reddish hue from the broken terrace walls<br />

rising along the northern margins <strong>of</strong> the river's broad,<br />

level plain.<br />

The shadows quickly lengthen among the thick stands<br />

<strong>of</strong> elm and oak that populate the bottoms, while<br />

willow and cottonwood keep a solitary vigil over the<br />

river's dark, moody waters. With the disappearance <strong>of</strong><br />

the sun's warming rays, an icy gale sweeps down <strong>of</strong>f<br />

the high plains, transforming the serene green ribbon<br />

<strong>of</strong> forest into a turbulent cacophony. In the dark<br />

purple twilight <strong>of</strong> the eastern sky, an eerie, cloudshrouded<br />

moon hangs low over the darkening hills,<br />

her half-light giving a surreal cast to the world below.<br />

Overhead, cold, pulsating beacons <strong>of</strong> light pierce the<br />

darkness. The winter stars rise slowly over the eastern<br />

horizon, harbingers <strong>of</strong> a changing season, <strong>of</strong> biting<br />

wind and numbing cold.<br />

In the distance, along the river's mist filled bottoms, a<br />

finger-like promontory protrudes from the upland<br />

divide and forces its way into the serpentine valley.<br />

Like the ocean tide, the thick fog rolls in, lapping at<br />

the steeply eroded flanks <strong>of</strong> the rocky, windswept<br />

prominence. Atop its level expanse, a huge, roaring<br />

fire licks at the smothering darkness, its flame dancing<br />

against a backdrop <strong>of</strong> hide-draped pole shelters,<br />

haphazardly thrown up against the raw wind. A<br />

procession <strong>of</strong> dark silhouettes circles the warming<br />

blaze while other figures sit motionless before the<br />

flame, its golden light revealing bronzed, weathered<br />

faces, etched by wind and sun. Wrapped in hide<br />

blankets against the gathering cold, they dreamily<br />

ponder the mystic movement <strong>of</strong> wood, smoke, and<br />

flame. Other hearths flicker to life throughout the<br />

small encampment, turning back the menacing<br />

encroachment <strong>of</strong> darkness. Off in a distant comer,<br />

several young boys sit huddled together, stones in<br />

hand, greedily shattering the long "morrow bones"<br />

from the day's kill. In another comer <strong>of</strong> camp, a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> women kneel, bison robes pulled close,<br />

punching, sewing, and s<strong>of</strong>tening leather, nursing<br />

babies, and discussing the abundance <strong>of</strong> meat from the<br />

day's successful hunt. While in another corner <strong>of</strong><br />

camp, kinsmen <strong>of</strong> the People gather around a small<br />

blaze tending sharpened sticks skewered with juicy<br />

chunks <strong>of</strong> red meat and inclined over sizzling, red<br />

coals. Young hunters excitedly hover around the<br />

elders, reenacting the events <strong>of</strong> the hunt earlier that<br />

day.<br />

A small group <strong>of</strong> bison slowly sauntered from the<br />

river's banks to graze on the upland pasture. As they<br />

made their way through the breaks, a small hunting<br />

party set the ambush. The small herd filed through a<br />

steep, narrow gorge. The hunters, armed with atlatls<br />

and darts tipped with dark grey and red banded, fluted<br />

points, followed the small herd up the draw, while<br />

others peered cautiously over the chasm's rim. The kill<br />

was fast and efficient. From above, a cloud <strong>of</strong> flint<br />

tipped lances descended on the unsuspecting prey with<br />

lightning speed. Suddenly panicked, the cows and<br />

their young stampeded up the steep-sided gulch.<br />

Thundering forward, the wild-eyed wave <strong>of</strong> brown<br />

bison trampled the bleached bones <strong>of</strong> their kindred<br />

scattered across the canyon floor. Grunting forms,<br />

hooves pounding, the air swirled with suffocating,<br />

powdery, red dust. Pushing, shoving, cows and calves<br />

alike struggled to keep their footing; they came<br />

bearing down on the grim form <strong>of</strong> a power-laden<br />

skull, horned and emblazoned across its brow with the<br />

mystical red zigzag <strong>of</strong> the lightning bolt. Careening<br />

forward, the lead cows came suddenly to the head <strong>of</strong><br />

the draw, turning abruptly only to meet the remainder<br />

<strong>of</strong> the oncoming herd. Amid the chaos <strong>of</strong> colliding<br />

bodies, trampled in the wild confusion, frantic cows<br />

bellowed and men shrieked. Sleek, feathered darts<br />

pierced the choking dust swirling on the hot, dry air <strong>of</strong><br />

that late summer day.<br />

For a time, the People will eat their fill. As in<br />

countless generations past, hunters have survived by<br />

the kill, while the old ones rekindle tales <strong>of</strong> bygone<br />

glories, <strong>of</strong> injuries, death, hunger, and starvation. The<br />

young sit silently on their haunches, listening intently,<br />

but ready to leap to their feet and recount their own<br />

brave deeds. Their shadows dance wildly against the<br />

shelter walls, and the flames from the central fire leap<br />

high into the night sky, reenacting its own ageless<br />

6<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

dance. Beyond the wall <strong>of</strong> night, prowling carnivores<br />

make their presence known, warning cries fending <strong>of</strong>f<br />

intruders from the remains <strong>of</strong> the old kill.<br />

Within the confines <strong>of</strong> fire and family, the small band<br />

is safe and warm, and bellies full for another day.<br />

These Folsom-age kills transpired in a side canyon <strong>of</strong><br />

the Beaver River, not far from its -confluence- with –<br />

Wolf Creek and Ft. Supply. The site, its remains<br />

heavily eroded by the shifting course <strong>of</strong> the Beaver<br />

some eight hundred years previous, consisted <strong>of</strong> a<br />

once extensive bone bed created by three separate<br />

hunting episodes. All three kills were made in late<br />

summer or early autumn, after the rutting season, as<br />

was evident from tooth-eruption analysis and the<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> bull remains. Points from the first and<br />

second kills were manufactured from Alibates and a<br />

unique form <strong>of</strong> Edwards chert found along the<br />

northeast rim <strong>of</strong> the plateau. Points from the third<br />

episode were <strong>of</strong> Alibates and Niobrara. By comparing<br />

the degree <strong>of</strong> retooling to the point's length, and then<br />

comparing the Cooper points to those at Elida, Folsom<br />

and Lipscomb, it was hoped that some light could be<br />

shed on the population movements <strong>of</strong> these Folsom<br />

hunters. At Cooper, the skeletons were articulated,<br />

and the butchering concentrated primarily on<br />

retrieving the hump and shoulder meat, choice pieces.<br />

The tongue and brains were not utilized. This is in<br />

contrast to the butchering techniques used at the late<br />

Archaic Certain site west <strong>of</strong> Elk City. These Archaic<br />

hunters removed the long bones, tongues and brains.<br />

In addition, they knew how to set a good table,<br />

feasting on succulent, roasted ribs.<br />

archeologist's search continues and you can be a<br />

participant in this ongoing work. Start by delving into<br />

the mysteries being uncovered, the silent earth<br />

reluctantly revealing only some <strong>of</strong> its secrets as each<br />

layer <strong>of</strong> dark, pungent soil is peeled back like the<br />

pages <strong>of</strong> an ancient text.<br />

From the very beginning Lee tells his readers to<br />

bypass anything that seems overly technical or<br />

mundane. Hey, don't sell yourself short. You paid<br />

good money for this book and you are spending<br />

valuable time reading it. Slog your way through every<br />

printed word; digest every jot and tittle, and don't<br />

snooze through the boring stuff. Become a part <strong>of</strong> this<br />

grand adventure. The face <strong>of</strong> this primal land<br />

continues in a constant state <strong>of</strong> flux, but some things<br />

remain constant. The winds continue to blow; the<br />

heavenly bodies move along their timeless paths<br />

across the sky, and, in the evening calm, ominously<br />

billowing clouds once again climb above the western<br />

horizon, bringing with them their precious gift <strong>of</strong> rain.<br />

Though the People are now gone, their shadows<br />

remain.<br />

Rock Art<br />

By Seth Hawkins<br />

Who were these people? Where did they come from,<br />

and what became <strong>of</strong> them? By what name were they<br />

known? When they looked into the black night, what<br />

did they fear? What stories did the sun, moon, and<br />

stars tell them? What secret knowledge did their<br />

shamans posses? Who did they marry. and by what<br />

rules were they considered kin? What <strong>of</strong> their<br />

distinctive lithic technology? When, where and why<br />

was the fluted Folsom point developed, and when,<br />

why, and with what new technology was it replaced?<br />

We have only a "snapshot" <strong>of</strong> several <strong>of</strong> their kills at<br />

Cooper, but where did they establish their temporary<br />

camps in order to process those kills, to refit, to<br />

recuperate, and celebrate their good fortune? The<br />

7<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

An Old-Fashioned Hoe, Down in Northwestern <strong>Oklahoma</strong><br />

Michael W. McKay and Leland C. Bement<br />

The Late Prehistoric period on the southern Plains<br />

(1500-500 years B.P.), particularly in northwestern<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong>, is an expression <strong>of</strong> semi-sedentary bison<br />

hunters subsidizing their diet through generalized<br />

gathering <strong>of</strong> wild plants and small game. More<br />

importantly, however, is the evidence <strong>of</strong> burgeoning<br />

horticulture, particularly during the Plains Village<br />

period (1000-500 years B.P.) when subsistence<br />

regimes included farming <strong>of</strong> tropical cultigens such as<br />

beans, squash, and corn. Historical accounts suggest<br />

corn horticulture was the primary component <strong>of</strong><br />

indigenous diets by the time <strong>of</strong> European contact<br />

(Bell, 1984, Brook 1989, 1994; Drass 1998, Lintz<br />

1984, Wedel 1961).<br />

The mixed but stable diet <strong>of</strong> the Late Prehistoric<br />

greatly altered native lifeways. Small-scale farming<br />

allowed villages to support larger numbers <strong>of</strong> people<br />

and this, in turn, necessitated settlement in areas<br />

where more arable land was accessible for farming.<br />

Plains Village period sites, in particular, are notable<br />

for their locations along major drainage systems and<br />

large tributaries. Generally, settlement density<br />

increases during the Plains Village period, and these<br />

settlements occupy steep terraces, high mesas, and<br />

elevated knolls within floodplain settings where<br />

porous, loamy sands are more amenable to hand<br />

cultivation.<br />

Four unique cultural complexes have been generated<br />

for the regions surrounding and including<br />

northwestern <strong>Oklahoma</strong> during the Late Prehistoric<br />

period (Figure 1). To the west, occupying what are<br />

presently the Texas and <strong>Oklahoma</strong> panhandles, is the<br />

Antelope Creek phase <strong>of</strong> the Upper Canark variant.<br />

Aside from geographic positioning along major<br />

stream and riverbeds in the panhandle region, notable<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> Antelope Creek sites are an<br />

abundance <strong>of</strong> stone masonry foundation dwellings<br />

with central floor channels and platforms, large<br />

amounts <strong>of</strong> cordmarked ceramics and imported<br />

Puebloan-design ceramics from the southwestern<br />

U.S., and an affinity for Alibates agatized dolomite in<br />

the chipped stone inventory. Alibates was used to<br />

produce a characteristic Antelope Creek phase tool,<br />

the diamond-beveled knife (Brooks 1989, Lintz 1984,<br />

1986).<br />

8<br />

The second regionally associated Late Prehistoric<br />

complex is the Redbed Plains variant. Notable<br />

characteristics <strong>of</strong> the Redbed Plains variant are large<br />

villages located on the floodplains <strong>of</strong> the Washita<br />

River and its major tributaries in west-central<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong>. Redbed Plains groups farmed intensively<br />

along these floodplains, utilizing bone resources for<br />

their cultivation toolkit. Additionally, western Redbed<br />

Plains groups share the same affinities for Alibates<br />

agatized dolomite as do Antelope Creek peoples<br />

(Brooks 1987, 1989; Drass 1998).<br />

A third cultural tradition, known as the Zimms<br />

complex, is wedged between the Upper Canark and<br />

Redbed Plains groups. The Zimms complex is as yet<br />

poorly understood, and its definition is based upon an<br />

artifact assemblage that does not quite align with the<br />

cultural traditions on either side. Dating between A.D.<br />

1250 and 1450, Zimms peoples are thought to have<br />

occupied the westernmost reaches <strong>of</strong> the Washita<br />

River in far western <strong>Oklahoma</strong>, but were primarily<br />

located along the Canadian, Cimarron, and Beaver<br />

Rivers <strong>of</strong> northwest <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. Lintz (1986) views the<br />

Zimms complex as part <strong>of</strong> the Upper Canark variant<br />

since the three Zimms-related sites have dwellings<br />

with floor channels and platforms. Alternately, Drass<br />

and Moore (1987) have suggested that the Zimms<br />

complex is intrusive to western <strong>Oklahoma</strong> as Zimms<br />

sites lack the signature masonry foundations <strong>of</strong> Upper<br />

Canark dwellings, and unlike either Antelope Creek or<br />

the Redbed Plains groups, Zimms sites possess very<br />

limited numbers <strong>of</strong> bone horticultural implements and<br />

over 90% <strong>of</strong> the ceramic assemblage is plain, smoothsurfaced<br />

pottery (Brooks 1994; Drass and Moore<br />

1987; Drass et. al. 1987; Moore 1988; McKay et. al.<br />

2004).<br />

A fourth cultural complex lies to the north,<br />

geographically situated in what are presently<br />

Comanche, Clark, and Meade counties at the<br />

southwestern border <strong>of</strong> Kansas. The Wilmore complex<br />

was defined by Kansas State Historical Society<br />

archaeologists during a 1984 survey <strong>of</strong> four sites<br />

located on the upland hills above the breaks <strong>of</strong> major<br />

tributaries on the northern rim <strong>of</strong> the Cimarron River<br />

drainage (Bevitt 1994). Like the Zimms complex, the<br />

Wilmore complex is as yet poorly understood, being<br />

defined only by surface survey and limited<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 1: Late Prehistoric cultural complexes and relevant site locations.<br />

excavation. Collectively, the Wilmore complex sites<br />

fit within the Plains Village tradition. The settlement<br />

pattern consists <strong>of</strong> small, dispersed individual<br />

habitations or small farming hamlets positioned along<br />

perennial, spring-fed streams. Dwellings generally<br />

have semi-subterranean floors; ceramics are<br />

characterized by decorated rim, smoothed cordmarked<br />

vessels; and chipped stone tools consist <strong>of</strong> Washita<br />

and Fresno arrow points, drills, perforaters??, gravers,<br />

and diamond-beveled or ovate knives. Horticultural<br />

tools are primarily <strong>of</strong> bison and deer bone. Bison<br />

scapula hoes are uniquely prepared through the<br />

removal <strong>of</strong> the glenoid head in addition to other blade<br />

reduction procedures such as removal <strong>of</strong> the scapular<br />

spine and beveling <strong>of</strong> the blade edge. Along with a<br />

large number <strong>of</strong> bison scapula hoes, there are many<br />

bison tibia digging stick tips, bison ulna picks, and a<br />

quantity <strong>of</strong> deer mandible sickles.<br />

Most Late Prehistoric artifact assemblages from<br />

northwestern <strong>Oklahoma</strong> and its surrounding regions<br />

produce quantities <strong>of</strong> fragmented and well-used bone<br />

9<br />

cultivation implements like bison and deer scapula<br />

hoes and tibia digging-stick tips. Rarely are there any<br />

chipped stone horticultural tools included in southern<br />

Plains assemblages. However, a recent find from the<br />

Smith #2 site (34HP138) in southeast Harper County<br />

(McKay et. al. 2004), as well as four other chipped<br />

stone hoes now document the use <strong>of</strong> stone hoes by<br />

Late Prehistoric groups. The five implements come<br />

from distinct but closely associated topographical<br />

settings and therefore, provide an opportunity for<br />

comparative analysis <strong>of</strong> variation in Late Prehistoric<br />

traditions <strong>of</strong> the northwestern <strong>Oklahoma</strong> region.<br />

Let’s Talk About the Hoe Collection<br />

The Lonker Site (34BV4)<br />

A fragment <strong>of</strong> a metamorphosed quartzite hoe was<br />

recovered during site mitigation from a badly<br />

disturbed, 110 x 90 x 25 cm refuse pit (Feature 5, see<br />

Figure 2), which held very little cultural material in<br />

total (Brooks 1994). Radiometric dating <strong>of</strong> associated<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 2. Topographic view <strong>of</strong> the Lonker Site (34BV4) and the location <strong>of</strong> relevant features (based on Brooks<br />

1994:Figure 3).<br />

pit Features 3 and 4 produced calibrated dates <strong>of</strong> 715<br />

± 50 years B.P. (Beta-4716) and 750 ± 40 years B.P.<br />

(Beta-4717) respectively, indicating an occupation <strong>of</strong><br />

the Lonker site circa A.D. 1260-1290. This time frame<br />

places the Lonker site in the middle <strong>of</strong> the southern<br />

Plains Village period, making site occupants<br />

contemporaneous with the early Upper Canark<br />

tradition (Brooks 1994, Lintz 1984, 1986).<br />

The hoe fragment’s definition was based upon its high<br />

degree <strong>of</strong> dorsal polish and a large number <strong>of</strong> linear<br />

striations (Brooks 1994). Unfortunately, the fragment<br />

is so small that striation direction is indeterminate. No<br />

dimensions were recorded for the hoe fragment nor<br />

was there discussion <strong>of</strong> material quality or color.<br />

Smith #2 Site (34HP138)<br />

A very large, elongated rectangular, bifacially<br />

knapped stone hoe was removed from the floor <strong>of</strong> a<br />

1m x 1m storage-turned-refuse pit at The Smith #2<br />

site. This site is positioned atop the ridge <strong>of</strong> a high,<br />

10<br />

upland knoll located at the edge <strong>of</strong> the southern breaks<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Cimarron River drainage in southeastern Harper<br />

County (McKay et. al. 2004). Radiometric dating <strong>of</strong><br />

carbonized corn from the pit feature indicates site<br />

occupation circa A.D. 1400-1450 (Beta-195762 and<br />

Beta-189107) associating the site with the southern<br />

Plains Village period. Based upon the large quantity<br />

<strong>of</strong> associated surface artifacts and the presence <strong>of</strong> two<br />

burned post molds and a large storage pit, the site was<br />

most likely a small farming hamlet. The quantity <strong>of</strong><br />

burned corn kernels and cob pieces removed during<br />

excavation <strong>of</strong> the pit feature suggests small-scale<br />

farming occurred either atop the knoll, or within the<br />

small playa zones encircling the knoll. The presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kansas pipestone as well as large quantities <strong>of</strong> Flint<br />

Hills chert in the artifact assemblage suggests that the<br />

Smith #2 occupants were involved in long distance<br />

exchange, or were non-local peoples that had<br />

imported non-local resources upon arrival. Such was<br />

the case with the chipped stone hoe.<br />

Measuring 24 x 8 x 4.3 cm, the hoe was manufactured<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 3. Chipped stone hoes from northwestern <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. (a.) Siltstone hoe from Smith #2 site (34HP138); (b.)<br />

Day Creek chert hoe from Harper County; (c.) Florence B hoe from Texas County (IF 0-193).<br />

from a high-quality, chocolate-brown siltstone (Figure<br />

3a), similar in color but texturally different from some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ferruginous Dakota quartzite found in local<br />

beds <strong>of</strong> Ogallala outwash gravels. The source <strong>of</strong> the<br />

siltstone material is unknown. Though amenable to<br />

knapping, the siltstone core is <strong>of</strong> a texture similar in<br />

coarseness to metaquartzite, making reduction<br />

thinning possible but difficult. The hoe, thus, has a<br />

high central ridge and faces that are somewhat<br />

convex. The convexity <strong>of</strong> both faces is equal; one face<br />

is not more flattened than the opposite. A small patch<br />

<strong>of</strong> cortex remains on the ridge <strong>of</strong> one face. The<br />

11<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

implement is <strong>of</strong> considerable length, yet there is no<br />

curvature to the tool when viewed in pr<strong>of</strong>ile.<br />

Therefore, it is thought that the hoe was manufactured<br />

from a tabular cobble or lensatic fragment <strong>of</strong> siltstone.<br />

The siltstone hoe is bifacially flaked by alternately<br />

removing a number <strong>of</strong> very large flakes from both<br />

sides and from each end. This knapping technique<br />

produced lateral edges that are straight and only<br />

slightly sinuous. One end <strong>of</strong> the stone is slightly<br />

broader than the other, and this wider end is the only<br />

point on the tool from which any small flakes have<br />

been bifacially removed, giving that end a serrated<br />

appearance. It is assumed that this broader, serrated<br />

end would have been the bit end. Neither end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

tool exhibits blunting/dulling nor polish. In fact, the<br />

only region where edge grinding appears to have been<br />

applied is along the lateral margins <strong>of</strong> both edges<br />

beginning at midline and moving distally 5 cm.<br />

Smoothing and slight polish across the midpoint <strong>of</strong> the<br />

implement suggests hafting <strong>of</strong> the tool.<br />

Due to its interment within the pit feature, one side <strong>of</strong><br />

the hoe has been heavily calcined, leaving behind a<br />

patina which obscures any possible use-wear<br />

signatures that may be present. Other than edge<br />

grinding and slight polish, no notching or other<br />

indications <strong>of</strong> hafting technique are present. The lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> end or blade polish, striations, or blunting indicates<br />

that the tool had been deposited unused or with<br />

minimal use for storage and later retrieval.<br />

Sleeping Bear Creek Isolated Find, Harper County<br />

A large, elongated oval chert hoe was discovered atop<br />

an upland terrace overlooking Sleeping Bear Creek<br />

near the southern breaks <strong>of</strong> the Cimarron River<br />

drainage system in Harper County (Figure 3b).<br />

Obtained by a collector in the 1930’s, the exact<br />

provenience for this tool is uncertain. However, the<br />

general setting for this find is less than 8 kilometers (5<br />

miles) north <strong>of</strong> the Smith #2 site. Based upon its<br />

outward gray-mottled appearance and luminescence<br />

signature, the hoe was manufacture from Day Creek<br />

chert, a local lithic resource found atop the<br />

Cimarron/Beaver River divide in present-day Harper<br />

County. In fact, Day Creek chert sources are located<br />

only 3.2 kilometers north <strong>of</strong> the Smith #2 site<br />

discussed previously, and within 4.8 kilometers<br />

southeast <strong>of</strong> the zone where the Harper County<br />

Isolated Find was thought to have been discovered<br />

(see Figure 1).<br />

Judging by the convexity <strong>of</strong> the tool when viewed in<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile, as well as the residual knapping platform on<br />

the poll end <strong>of</strong> the tool, the hoe was produced from a<br />

very large flake core. The flake core was bifacially<br />

flaked for thinning, leaving behind no cortex and<br />

producing a tool with a length <strong>of</strong> 17.6 cm, and an<br />

average thickness <strong>of</strong> 2.8 cm. The width <strong>of</strong> the tool’s<br />

bit end is 9.4 cm, while the poll measures 7.4 cm<br />

across. Because <strong>of</strong> large, deep flake scars, the lateral<br />

edges appear quite sinuous. Edge grinding is apparent<br />

around the tools lateral periphery. The hoe has an<br />

hourglass shape due to deep hafting notches placed<br />

immediately distal <strong>of</strong> midline. The hoe is 6.6 cm wide<br />

at the notches, and the notches have an average length<br />

<strong>of</strong> 3.6 cm and an average depth <strong>of</strong> 0.6 cm. The lateral<br />

edges <strong>of</strong> the notches are more heavily ground and<br />

blunted than the rest <strong>of</strong> the lateral periphery.<br />

The implement has a 2 cm wide, cream-colored vein,<br />

centrally located on the ventral face that courses the<br />

tool’s entire length. The cream-colored inclusion or<br />

defect is likely the reason this particular flake was<br />

chosen to produce a digging implement, rather than<br />

another tool form. Day Creek chert is <strong>of</strong>ten riddled<br />

with defects such as large phenocrystic vesicles, or<br />

veins <strong>of</strong> differing chert textures. In fact, the mixing <strong>of</strong><br />

cream-, blue- and gray-colored material is common.<br />

The fact that the cream-colored portion <strong>of</strong> the flake<br />

has not been altered to a pink or rose color indicates<br />

that the flake core was probably not heat-treated. The<br />

cream-colored vein is not visible on the dorsal face.<br />

Use-related polish is apparent on both tool faces, but<br />

more prominent on the dorsal side <strong>of</strong> the flake<br />

implement. Polish on the dorsal side extends to within<br />

2 cm <strong>of</strong> the poll end <strong>of</strong> the tool. The bit is heavily<br />

battered and crushed. Flake scars on the dorsal side <strong>of</strong><br />

the flake’s bit end are partially obliterated from usewear.<br />

Striations are not observed on either the dorsal<br />

or ventral surfaces, probably due to the hardness <strong>of</strong><br />

Day Creek chert.<br />

Texas County Isolated Find 0-193 (part <strong>of</strong> the Ralph<br />

White Collection at the Sam Noble <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Museum<br />

<strong>of</strong> Natural History)<br />

As discussed by Lintz and White (1980), a teardropshaped<br />

stone hoe was discovered in a blowout along<br />

G<strong>of</strong>f Creek in what is now Texas County, <strong>Oklahoma</strong>.<br />

Similar to the topographical setting <strong>of</strong> Smith #2, the<br />

G<strong>of</strong>f Creek blowout was positioned within the gently<br />

rolling sand hills <strong>of</strong> the Beaver River’s northern<br />

breaks. Compared to the Smith #2 stone hoe, TXIF 0-<br />

12<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

193 is much shorter, narrower, and thinner, measuring<br />

18 x 5 x 2.2 cm (Figure 3c).<br />

Based upon its original beige color, fragmented<br />

diatomaceous inclusions, and red color transformation<br />

caused by heat-treatment, it is thought that the chert<br />

resource used to produce TXIF 0-193 is a form <strong>of</strong><br />

Florence B chert, found in the Flint Hills region <strong>of</strong><br />

Kansas and extreme north-central <strong>Oklahoma</strong><br />

(<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archaeological Survey comparative<br />

collection: Florence chert #3). The chert cobble<br />

appears to have been heat-treated prior to knapping,<br />

making the material more brittle, texturally uniform,<br />

and amenable to controlled flake removal. There is no<br />

curvature <strong>of</strong> the tool when viewed in pr<strong>of</strong>ile,<br />

suggesting the tool was manufactured from a tabular<br />

or lensatic cobble <strong>of</strong> chert, rather than from a large<br />

flake core. The lateral edges are straight, having been<br />

bifacially flaked. This has left not only a somewhat<br />

rounded central ridge grading into convex faces, but<br />

lateral edges that are minimally sinuous. Both faces<br />

are equal in convexity.<br />

The tool is teardrop-shaped. The wide end, thought to<br />

be the tool’s bit based upon the presence <strong>of</strong> heavy<br />

polish and linear striations, measures 2.2 cm across,<br />

while the opposite end measures 1.9 cm. The only<br />

cortex noted on the tool is a small platform <strong>of</strong><br />

patinated material located adjacent to the poll or<br />

narrower end <strong>of</strong> the tool. The entire periphery <strong>of</strong> the<br />

tool appears to have been ground and blunted. The bit<br />

end has been crushed and rounded from continual<br />

battering. Either hafting or use polish is evident across<br />

the entire tool surface; however, one face has far more<br />

polish and linear striations, particularly near the bit<br />

end (see Lintz and White 1980:4, Figure 1). In fact,<br />

the polish is so extensive that it practically obliterates<br />

flake scars on the bit end. Because <strong>of</strong> the intensity <strong>of</strong><br />

use-wear on one side versus the opposite, the<br />

implement is thought to be a hoe, rather than an adze<br />

or axe that would be expected to have equal wear on<br />

both sides.<br />

The Booth Site (14CM406)<br />

Radiocarbon dating suggests that the Booth site was<br />

occupied between A.D. 1307 and 1638. During its<br />

occupation, a number <strong>of</strong> pit features and dwelling<br />

structures had been constructed. A fragment <strong>of</strong> an<br />

elongated, leaf-shaped biface (see Bevitt 1994:84,<br />

Figure 23) manufactured from Dakota quartzite was<br />

recovered from one <strong>of</strong> these pit features during<br />

excavation. Feature 247 is a circular, straight-walled,<br />

flat-floor pit that appeared to have been truncated by a<br />

later semi-subterranean house structure (Feature 101).<br />

Feature 247 contained dense collections <strong>of</strong> mussel<br />

shell and bone fragments interspersed with ceramic<br />

and lithic artifacts, including the biface fragment. All<br />

materials were suspended in a dark, gray-brown soil<br />

matrix. The biface fragment was later matched with<br />

fragments from a donated surface collection. The<br />

complete implement exhibits extensive use-related<br />

abrasion on both ends and quite extensive abrasion<br />

along the central ridges <strong>of</strong> each face. No mention is<br />

made <strong>of</strong> residual hafting signatures, retained cortex, or<br />

the type <strong>of</strong> core (tabular or flake) from which the tool<br />

was produced. The lateral margins <strong>of</strong> the tool were<br />

heavily rounded from use, and a number <strong>of</strong> flake scars<br />

were nearly obliterated. Numerous striations were<br />

noted running parallel with the long axis <strong>of</strong> the tool<br />

and due to these characteristics the tool is considered<br />

to be a digging implement.<br />

Discussion<br />

There is a distance <strong>of</strong> more than 48.3 kilometers (30<br />

miles) between the Booth site in Comanche County,<br />

Kansas, and the Harper County finds and greater than<br />

64.3 kilometers (40 miles) between the Lonker site<br />

and the Harper County finds. There is an even greater<br />

distance between Lonker and the G<strong>of</strong>f Creek stone<br />

hoe further west in Texas County, yet all <strong>of</strong> these sites<br />

where chipped stone hoes have been recovered can<br />

still be considered regionally associated making it<br />

plausible that Late Prehistoric groups producing these<br />

rare hoes were culturally related.<br />

Contextual dates have been established on three <strong>of</strong> the<br />

chipped stone hoes - A.D. 1260-1290 for the Lonker<br />

site hoe fragment, A.D. 1400-1450 for the Smith #2<br />

siltstone hoe, and A.D. 1307-1638 for the Booth site<br />

hoe. All dates fall within the Plains Village period.<br />

The five chipped stone hoes in this collection were<br />

found on upland terraces adjacent to breaks feeding<br />

large tributaries <strong>of</strong> major river systems. This fact,<br />

coupled with the nature <strong>of</strong> Late Prehistoric lifestyles<br />

and the intensification <strong>of</strong> farming, leads to the<br />

assumption that the two isolated chipped stone hoes<br />

might also fit into the Plains Village temporal setting.<br />

While geographic and temporal similarities within the<br />

chipped stone hoe collection can be used to relate the<br />

regional groups producing chipped stone hoes,<br />

diagnostic features <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the hoes produces quite<br />

a different picture. Each <strong>of</strong> the five hoes is quite<br />

unique, having been manufactured from distinct lithic<br />

13<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

materials. Two <strong>of</strong> these lithic resources are not found<br />

locally. Both <strong>of</strong> the tools produced from non-local<br />

resources are manufactured from tabular cores, while<br />

the Day Creek chert hoe, made from a local resource,<br />

is produced from a large flake. Attributes <strong>of</strong> the parent<br />

cores for the Lonker and Booth site cores remain<br />

indeterminate.<br />

It appears that chipped stone hoes were heavily<br />

curated with a large quantity <strong>of</strong> labor invested in their<br />

production, use, and maintenance. All five implements<br />

were produced through bifacial flake reduction<br />

methods, removing the majority <strong>of</strong> the cortex from the<br />

core. The two implements manufactured from nonlocal<br />

resources were knapped in such a way as to<br />

leave straight, minimally sinuous lateral edges, while<br />

lateral edges that were quite sinuous were left on the<br />

Day Creek chert hoe. Additionally, only the Florence<br />

B hoe from Texas County appears to have been heattreated<br />

prior to manufacture.<br />

None <strong>of</strong> the complete stone hoes match in plan view.<br />

Each has a different morphology: teardrop,<br />

rectangular, leaf-shaped, and hourglass. However, all<br />

three are knapped such that a central ridge remains on<br />

both faces, and both faces on each tool are equally<br />

convex. Only the Day Creek chert hoe is notched for<br />

hafting. Slight grinding modifications are found on the<br />

lateral edges <strong>of</strong> the Smith #2, Booth, and Texas<br />

County hoes, but hafting polish can not be identified<br />

or distinguished from use-related polish.<br />

Due to the variability <strong>of</strong> resources used to<br />

manufacture the five chipped stone hoes, there is no<br />

consistent pattern in the use-wear signatures. The<br />

siltstone hoe from Smith #2 had been stored unused<br />

and therefore possessed little to no use-wear. In<br />

contrast, the Day Creek chert hoe from Harper County<br />

is heavily polished by the abrasion <strong>of</strong> silicates as the<br />

implement continually entered and pulled the sandyloam<br />

soils. The Lonker and Booth site hoe fragments<br />

and the Florence B chert hoe from Texas County all<br />

exhibit the same heavy polish as the Day Creek chert<br />

hoe. However, either because they were manufactured<br />

from s<strong>of</strong>ter lithic material than Day Creek chert or<br />

because they were used to perform different<br />

cultivating tasks than the Day Creek chert hoe, there<br />

are numerous linear striations present on their blade<br />

faces that are not apparent on the Day Creek chert<br />

hoe.<br />

The Florence B chert hoe exhibits greater polish and<br />

more striations on one side versus the other; however,<br />

it is unknown whether hoe blades were rotated and<br />

rehafted prehistorically, a technique that would have<br />

exposed each face to alternating intensities <strong>of</strong> wear<br />

during their use-life. In a study concerning wear<br />

patterns on bison scapula hoes from a number <strong>of</strong><br />

Redbed Plains variant sites, Davis (1965) notes a usewear<br />

study performed on chipped stone hoes by<br />

Sergei Semenov (1964). Semenov states that the most<br />

prominent indicator <strong>of</strong> a tool being used as a hoe is the<br />

wear distribution across each face. Due to hafting and<br />

the angle <strong>of</strong> use, polish and linear striations will<br />

predominate on the outside face <strong>of</strong> a hoe blade.<br />

The stone hoes from Smith #2 and the Booth site<br />

broaden Late Prehistoric horticultural tool<br />

assemblages that already included bison scapula hoes<br />

and tibia digging stick tips. The presence <strong>of</strong> both stone<br />

and bone implements suggests the need for a digging<br />

implement that is stronger than bone. The upland<br />

setting <strong>of</strong> these finds provides contexts where stone<br />

implements are more desirable than bone. At Smith<br />

#2, the storage pit was dug into dune clay that would<br />

have been impervious to bone tools. In fact, because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the soil density, archaeologists had trouble cutting a<br />

clean pr<strong>of</strong>ile across the feature’s face using modern<br />

steel shovels. In this regard, the modern definition <strong>of</strong><br />

these stone implements might be closer to the<br />

description <strong>of</strong> a “mattock”, rather than a “hoe”.<br />

Finally, the setting from which all five chipped stone<br />

implements were recovered is intriguing. All five sites<br />

are located in the upland hills bordering breaks that<br />

are nearly a mile (1.6 kilometers) from the sandchoked<br />

channels <strong>of</strong> braided stream systems. Most <strong>of</strong><br />

the nearby streambeds tend to flow ephemerally,<br />

usually carrying only run<strong>of</strong>f precipitation.<br />

As discussed by Lintz and White (1980:5),<br />

horticulture in this upland dune setting is more akin to<br />

wild plant harvesting. Quoting ethnographic records,<br />

Lintz and White state that digging implements like<br />

chipped stone hoes were likely used to extract tubers<br />

and roots such “…as Indian turnip (Psoralea<br />

esculenta and hypogea), bush morning glory (Ipomoea<br />

ieptophylla), and Jerusalem artichoke (Helianhus<br />

tuberosus) (that) were important dietary supplements,<br />

while wild plum roots (Prunus spp.), and yucca<br />

(Yucca spp.) had medicinal uses.” The quantity <strong>of</strong><br />

charred corn apparent in the Smith #2 storage pit<br />

indicates that upland farmers were participating in<br />

intensive cultivation <strong>of</strong> tropical cultigens, though<br />

charred blue-funnel lily corms in the pit fill<br />

substantiates at least the subsidizing <strong>of</strong> farming with<br />

14<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

wild plant gathering including some subsurface plant<br />

parts. Extraction <strong>of</strong> the corms and probably other<br />

resources may, in fact, have necessitated the<br />

production and use <strong>of</strong> chipped stone implements<br />

(McKay et. al. 2004).<br />

References<br />

Bell, Robert E.<br />

1984 Prehistory <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. Academic Press,<br />

Orlando.<br />

Brooks, Robert L.<br />

1987 The Arthur Site: Settlement and Subsistence<br />

Structure at a Washita River Phase Village.<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong>, <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archaeological<br />

Survey, Studies in <strong>Oklahoma</strong>’s Past 15, Norman.<br />

1989 The Village Farming Societies. In From<br />

Clovis to Comanchero: Archaeological Overview <strong>of</strong><br />

the Southern Great Plains edited by J. L. H<strong>of</strong>man, R.<br />

L. Brooks, J.S. Hays, D.W. Owsley, R.L. Jantz, M.K.<br />

Marks, and M.H. Manhein pp. 71-90. Arkansas<br />

Archaeological Survey, Research Series No. 35,<br />

Fayetteville.<br />

1994 Variability in Southern Plains Village Cultural<br />

Complexes: Archaeological Investigations at the<br />

Lonker Site in the <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Panhandle. Bulletin <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Anthropological Society Bulletin 43:1-<br />

27.<br />

Davis, Michael K.<br />

1965 A Study <strong>of</strong> Wear on Washita River Focus<br />

Buffalo Scapula Tools. Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Oklahoma</strong><br />

Anthropological Society 13:153-159.<br />

Drass, Richard R.<br />

1998 The Southern Plains Villagers. In<br />

Archaeology on the Great Plains edited by W.<br />

Raymond Wood, pp. 415-455. <strong>University</strong> Press <strong>of</strong><br />

Kansas, Lawrence.<br />

Drass, Richard R. and Michael C. Moore<br />

1987 The Linville II Site (34RM92) and Plains<br />

Village Manifestations in the Mixed Grass Prairie.<br />

Plains Anthropologist 32:118:404-418.<br />

Drass, Richard R., Timothy G. Baugh, and Peggy<br />

Flynn<br />

1987 The Heerwald Site and Early Plains Village<br />

Adaptations in the Southern Plains. North American<br />

Archaeologist 8(2):151-190.<br />

Lintz, Christopher<br />

1984 The Plains Villagers: Antelope Creek. In<br />

Prehistory <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong> edited by Robert E. Bell, pp.<br />

325-346. Academic Press, New York.<br />

1986 Architecture and Community Variability<br />

within the Antelope Creek Phase <strong>of</strong> the Texas<br />

Panhandle, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong>, <strong>Oklahoma</strong><br />

Archaeological Survey, Studies in <strong>Oklahoma</strong>’s Past<br />

14. Norman.<br />

Lintz, Christopher and Bill White<br />

1980 A Chipped Stone Digging Implement from<br />

the <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Panhandle. <strong>Oklahoma</strong> Anthropological<br />

Society Newsletter 28:3.<br />

McKay, Michael W., Leland C. Bement, and Richard<br />

R. Drass<br />

2004 Testing Results <strong>of</strong> Four Late Holocene Sites<br />

Harper County, <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong>,<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archaeological Survey, Resource Survey<br />

Report No. 49. Norman.<br />

Moore, Michael C.<br />

1988 Additional Evidence for the Zimms Complex?<br />

A Re-evaluation <strong>of</strong> the Lamb-Miller Site, 34RM25,<br />

Roger Mills County, <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Anthropological Society 37:136-150.<br />

Semenov, Sergei A. (M. W. Thompson, translation)<br />

1964 Prehistoric Technology: An Experimental<br />

Study <strong>of</strong> the Oldest Tools and Artifacts from Traces <strong>of</strong><br />

Manufacture and Wear. Cory, Adams, and MacKay,<br />

London.<br />

Wedel, Waldo R.<br />

1961 Prehistoric Man on the Great Plains.<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Oklahoma</strong>. Press, Norman.<br />

15<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

The Certain Site Southern Plains Late Archaic Bison Kills<br />

Leland C. Bement and Kent J. Buehler<br />

Abstract<br />

Testing <strong>of</strong> a bison bone deposit at the base <strong>of</strong> a 25m<br />

sandstone cliff at the Certain site, 34BK46, western<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong>, yielded resharpening flakes and a<br />

butchering tool. These artifacts, plus the density <strong>of</strong><br />

bison remains suggest this cliff was used as a bison<br />

jump. Bone from this deposit was radiocarbon dated<br />

to 2200 ybp, some 300-400 years older than the bones<br />

in the arroyo kills for which the site is best known. In<br />

addition, we found another bison bonebed two meters<br />

deeper than the first. Although little excavation has<br />

been accomplished in this lower bonebed, we did<br />

recover a chert chip suggesting it too is the result <strong>of</strong> a<br />

bison jump. The two deposits at the base <strong>of</strong> the cliff<br />

make the Certain site the second confirmed bison<br />

jump on the southern Plains. The geomorphological<br />

history <strong>of</strong> the canyon provides the mechanism leading<br />

to the abandoning <strong>of</strong> the jump technique for the arroyo<br />

trap technique. Evidence <strong>of</strong> a shift in environmental<br />

conditions from xeric to mesic ushered in the<br />

Woodland horticulturalists.<br />

Introduction<br />

Bison hunters on the North American plains employed<br />

communal kill techniques including arroyo traps, sand<br />

dune traps, pounds, surrounds, and jumps. Examples<br />

<strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> these techniques are found in the<br />

archeological record on the northern plains (Frison<br />

1991). The same can not be said for the southern<br />

plains, where the majority <strong>of</strong> kills occurred in arroyo<br />

or sand dune traps. Bonfire Shelter (Dibble and<br />

Lorrain 1968; Bement 1986), in southwest Texas, has<br />

been the southern plains’ only example <strong>of</strong> a bison<br />

jump. Recent work at the Certain bison kill site,<br />

34BK46, in western <strong>Oklahoma</strong> yielded evidence for a<br />

second bison jump on the southern plains. Drawing on<br />

information provided by geomorphology, taphonomy,<br />

and archaeology, the Certain site jump may contain<br />

more than one jump episode.<br />

The Certain site is best known for its extensive arroyo<br />

trap kills located in several gullies along a 300m<br />

stretch <strong>of</strong> a spring fed tributary <strong>of</strong> Sandstone Creek<br />

(Bement and Buehler 1994; Buehler 1997). The<br />

arroyo kills date between 1800 and 1600 years ago.<br />

Large corner-notched dart points, hammerstones, and<br />

16<br />

resharpening flakes comprise the cultural material<br />

from these kills. Butchering and processing features<br />

accompany the kills, but, as yet, no formal camp site<br />

has been found.<br />

While the arroyo traps are located in short gullies on<br />

the north side <strong>of</strong> the canyon, the 25m high sandstone<br />

cliff is on the south side. At the base <strong>of</strong> this cliff, and<br />

on the downstream edge, are the bone deposits<br />

attributed to the jump (Figure 1, Area H). The bone<br />

deposit uncovered in 1997 dates 400 years older (2200<br />

bp) than the age <strong>of</strong> the arroyo kills. A second, lower<br />

bone deposit discovered during the 1998 excavation<br />

may extend the use <strong>of</strong> this site back further in time.<br />

Investigation <strong>of</strong> the upper bone deposit and the<br />

erosional surface bone in a 2x2m area yielded four<br />

resharpening flakes, one flake butchering tool, and the<br />

partial remains <strong>of</strong> at least seven individuals (based on<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> right mandibular diastema). The lower<br />

bone deposit was briefly exposed in a 50x50cm unit<br />

and contained portions <strong>of</strong> at least three bison (based<br />

on humerii) and a single chert chip. The lithics<br />

provide the cultural link to the bison remains. The<br />

context <strong>of</strong> the bones at the bottom <strong>of</strong> a 20+ m cliff<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers the interpretation that this is a jump site.<br />

Evidence <strong>of</strong> in situ Context<br />

Our argument that the bonebeds at the bottom <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cliff are in situ, primary deposits is found in the soil<br />

development, articulation <strong>of</strong> skeletal elements,<br />

taphonomy, and presence <strong>of</strong> gray sediments resulting<br />

from the microbial breakdown <strong>of</strong> organics left from<br />

the butchering <strong>of</strong> the animals. A pr<strong>of</strong>ile trench was cut<br />

along the downstream edge <strong>of</strong> the bone-bearing<br />

deposits. A description <strong>of</strong> the deposits in this trench<br />

(by Brian Carter, OSU) indicates roughly horizontal<br />

rather than vertical stratigraphy resulting from the<br />

erosion <strong>of</strong> sediments and then the collapse <strong>of</strong> more<br />

recent overburden to bury the exposed older deposit.<br />

The basic sequence is one <strong>of</strong> vertical bedrock face<br />

with vertically stratified sediment remnants set against<br />

it, then buried under colluvial materials from the top<br />

<strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>ile. The vertically stratified deposits are red<br />

silty sands with occasional small sandstone pebbles.<br />

Overlying colluvial material consists <strong>of</strong> mottled red<br />

and brown sandy loams with pockets <strong>of</strong> organic<br />

solum.<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

Figure 1. Bison arroyo traps and jump, Area H, at the Certain site.<br />

Geomorphic History <strong>of</strong> the Canyon<br />

The surface and near-surface geology <strong>of</strong> this portion<br />

<strong>of</strong> western <strong>Oklahoma</strong> are dominated by late<br />

Pleistocene to Holocene age sand dunes; Ogallala<br />

formation sands and gravels; and redbed sandstones <strong>of</strong><br />

Permian age. In the vicinity <strong>of</strong> the Certain site, the<br />

Ogallala deposits are merely deflated remnants<br />

composed primarily <strong>of</strong> gravels on hill tops or<br />

reworked into the drainage bottoms. Permian age<br />

sandstones outcrop in all drainages and most<br />

interfluvs.<br />

The canyon is cut into the Permian age sandstone and<br />

has undergone numerous cut and fill sequences--some<br />

<strong>of</strong> which we can date. By the time the gullies were<br />

employed, the main canyon had filled to within 3<br />

meters <strong>of</strong> the canyon rim, rendering the cliff to a 3 m<br />

drop and burying the cliff base deposits under 17 m <strong>of</strong><br />

fill.<br />

The gullies and canyon continued to fill during and<br />

after the use <strong>of</strong> the arroyo traps. During the early 20th<br />

century, it was possible to drive a tractor from one<br />

bank <strong>of</strong> the canyon to the other. Now, due to extreme<br />

17<br />

erosion, the 25 m deep canyon is once again being<br />

flushed <strong>of</strong> deposits.<br />

Sustained research into the documentation and dating<br />

<strong>of</strong> soil formation events in the canyon systems <strong>of</strong><br />

western <strong>Oklahoma</strong> by Pete Thurmond and Don<br />

Wyck<strong>of</strong>f has yielded evidence for cyclical xeric and<br />

mesic intervals averaging 400 years duration during<br />

the late Holocene. The period <strong>of</strong> arroyo use at Certain<br />

falls within one <strong>of</strong> the xeric periods. The cliff use<br />

predates the series documented by Thurmond and<br />

Wyck<strong>of</strong>f, but falls within a xeric period documented<br />

by others in the region (Ferring 1986; Hall 1982).<br />

Preliminary carbon isotopic analysis <strong>of</strong> bone from the<br />

various kill and processing events corroborates the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> the kill site during xeric periods.<br />

The sequence <strong>of</strong> site use has been reconstructed as<br />

follows. The cliff jump dates to around 2280 yrs. BP<br />

and carbon isotope analysis indicates these animals<br />

subsisted on a diet composed <strong>of</strong> 98% C4 xeric adapted<br />

grasses. The first <strong>of</strong> the arroyo traps (Trench C) dates<br />

to roughly 1760 yrs BP and these animals had a diet<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> nearly 95% C4 grasses. Trench A<br />

animals were killed around 1680 BP. By this time the<br />

<strong>Oklahoma</strong> Archeology, Vol. 53, No. 1

diet sees an increase in the C3 grass component <strong>of</strong> the<br />

diet although C4 grasses still dominate at 80%. The<br />

last arroyo kill for which we have data (Trench G)<br />

occurred around 1570 BP by which time the animals’<br />

diet consisted <strong>of</strong> only 61% C4 grasses. The nearly<br />