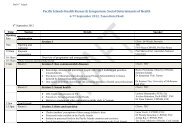

Follow this link to download the full report - HRH Knowledge Hub ...

Follow this link to download the full report - HRH Knowledge Hub ...

Follow this link to download the full report - HRH Knowledge Hub ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Most discussions of <strong>the</strong> precise impact of<br />

emigration and <strong>the</strong> nature of its relationship <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>HRH</strong> shortages within Pacific region countries<br />

are hampered by <strong>the</strong> lack of even <strong>the</strong> most<br />

basic data regarding numbers of emigrants,<br />

immigrants and returnees, relying instead on<br />

‘back of <strong>the</strong> envelope’ estimates.<br />

comprehensive examination of health workforce numbers in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pacific region was conducted more than 20 years ago<br />

(see Rotem & Dewdney 1991, referred <strong>to</strong> in Connell 2009b.)<br />

It is not surprising <strong>the</strong>n that a common feature of <strong>the</strong> country<br />

presentations is <strong>the</strong> need for workforce plan development;<br />

a finding which supports <strong>the</strong> observation that even though<br />

workplans have been developed in some countries, <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

unused because <strong>the</strong>y have been nei<strong>the</strong>r costed nor funded<br />

(Nukuro 2010).<br />

Also noteworthy is <strong>the</strong> way in which <strong>the</strong> impact of migration<br />

has been viewed by participants. Given <strong>the</strong> emphasis each<br />

country has placed on staff shortages, recruitment and<br />

retention problems within <strong>the</strong>ir respective health sec<strong>to</strong>rs,<br />

it is curious that an emphasis of similar magnitude has<br />

not been placed on <strong>the</strong> issue of migration. Although it is<br />

a phenomenon thought <strong>to</strong> be deeply implicated in <strong>the</strong><br />

development of staff shortages within countries of origin, and<br />

particularly so for small countries (Khadria 2010), participants<br />

have not given it <strong>the</strong> attention one might have expected. As<br />

noted earlier, seven countries nominated emigration as an<br />

issue or challenge, and only one (Tonga) included it among<br />

its needs and priorities.<br />

This should not be taken <strong>to</strong> mean, however, that emigration<br />

does not impact on <strong>the</strong> remaining countries. Indeed, <strong>the</strong><br />

significance of emigration (in all its forms) for <strong>the</strong> Asia Pacific<br />

region, where health systems are often fragile, has been a<br />

consistent <strong>the</strong>me within <strong>the</strong> literature for some time. (See<br />

for instance Iredale et al. 2003, IOM 2010, WPRO 2004).<br />

Unfortunately, however, most discussions of <strong>the</strong> precise<br />

impact of emigration and <strong>the</strong> nature of its relationship <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>HRH</strong> shortages within Pacific region countries are hampered<br />

by <strong>the</strong> lack of even <strong>the</strong> most basic data regarding numbers<br />

of emigrants, immigrants and returnees, relying instead<br />

on ‘back of <strong>the</strong> envelope’ estimates (Connell 2009b).<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, one thing is certain - <strong>the</strong> steady loss of skilled<br />

health workers through continuing international migration,<br />

internal mobility and movement from <strong>the</strong> public <strong>to</strong> private<br />

health sec<strong>to</strong>r places increasing pressure on already limited<br />

resources and struggling public health sec<strong>to</strong>rs. This is<br />

especially so where skilled health workers from o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

countries who can substitute for those who have emigrated<br />

cannot be found (Forcier et al. 2004) and where <strong>the</strong> loss of<br />

only a small number of skilled health workers makes a crucial<br />

difference <strong>to</strong> efficient and effective functioning of a health<br />

system (Pak & Tukui<strong>to</strong>nga 2006).<br />

A possible clue as <strong>to</strong> why emigration has not been nominated<br />

is <strong>to</strong> be found in <strong>the</strong> comment of a participant from Fiji who<br />

noted that <strong>the</strong>y produce 200 nurses per year <strong>to</strong> compensate<br />

for staff losses due <strong>to</strong> migration and retirement. Such a<br />

response clearly indicates that <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> expectation that a<br />

certain proportion of nursing graduates will migrate at some<br />

stage. Elsewhere, <strong>the</strong> General Secretary of <strong>the</strong> Fiji Nursing<br />

Association has been quoted saying that <strong>to</strong> work overseas is<br />

regarded as a ‘privilege’ because of <strong>the</strong> financial and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

returns it provides <strong>to</strong> relatives at home (Lutua 2002 quoted<br />

in Connell 2007: 70). There are also examples of countries<br />

actively encouraging <strong>the</strong>ir citizens <strong>to</strong> work and train overseas<br />

(eg. KANI – Kiribati).<br />

The question of motivations <strong>to</strong> migrate is one which has<br />

occupied researchers exploring <strong>the</strong> global migration patterns of<br />

people from <strong>the</strong> Pacific region. (For some recent examples see<br />

Barcham et al. 2009; Gibson et al. 2010; Lee 2009, Opeskin<br />

& MacDermott 2009.) It is also a <strong>to</strong>pic which is <strong>to</strong> be found in<br />

most discussions of migration patterns of skilled health workers<br />

within <strong>the</strong> Pacific region. (See for instance Brown & Connell<br />

2006, Henderson & Tulloch 2008, Oman 2007, Rokoduru<br />

2008, WPRO 2004.) A <strong>full</strong> exploration of <strong>this</strong> literature is<br />

well beyond <strong>the</strong> scope of <strong>this</strong> paper. What is important <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

present discussion, however, is <strong>the</strong> central place economic<br />

considerations occupy (including <strong>the</strong> family responsibilities<br />

and kinship obligations <strong>to</strong> contribute <strong>to</strong> household income<br />

through remittances) in decisions <strong>to</strong> migrate.<br />

Connell’s extensive and enduring research in<strong>to</strong> migration has<br />

led him <strong>to</strong> conclude that a culture of migration is in evidence<br />

within many Pacific Island cultures and that migration, far<br />

from being regarded as a problem <strong>to</strong> be removed, has come<br />

<strong>to</strong> serve a crucial economic role. Indeed, remittances have<br />

become an integral component of GDP within a number of<br />

PICs (Connell 2009a). Remittances <strong>to</strong> Tonga, for instance,<br />

<strong>the</strong> leading recipient of remittances, represent approximately<br />

45% of GDP (Lin 2010). Such a sizable proportion reflects<br />

<strong>HRH</strong> issues and challenges in 13 Pacific Islands countries: 2011<br />

Doyle et al.<br />

13