Overview of Capital Account Crisis - IMF

Overview of Capital Account Crisis - IMF

Overview of Capital Account Crisis - IMF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND<br />

<strong>Capital</strong> <strong>Account</strong> Crises: Lessons for <strong>Crisis</strong> Prevention<br />

Atish Ghosh 1<br />

July 2006<br />

I. INTRODUCTION<br />

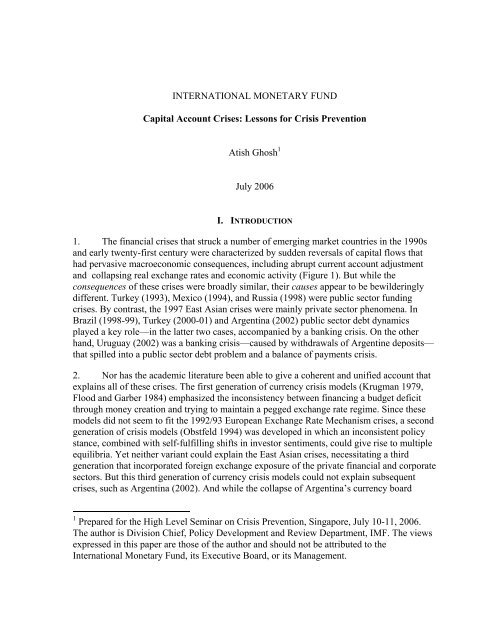

1. The financial crises that struck a number <strong>of</strong> emerging market countries in the 1990s<br />

and early twenty-first century were characterized by sudden reversals <strong>of</strong> capital flows that<br />

had pervasive macroeconomic consequences, including abrupt current account adjustment<br />

and collapsing real exchange rates and economic activity (Figure 1). But while the<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> these crises were broadly similar, their causes appear to be bewilderingly<br />

different. Turkey (1993), Mexico (1994), and Russia (1998) were public sector funding<br />

crises. By contrast, the 1997 East Asian crises were mainly private sector phenomena. In<br />

Brazil (1998-99), Turkey (2000-01) and Argentina (2002) public sector debt dynamics<br />

played a key role—in the latter two cases, accompanied by a banking crisis. On the other<br />

hand, Uruguay (2002) was a banking crisis—caused by withdrawals <strong>of</strong> Argentine deposits—<br />

that spilled into a public sector debt problem and a balance <strong>of</strong> payments crisis.<br />

2. Nor has the academic literature been able to give a coherent and unified account that<br />

explains all <strong>of</strong> these crises. The first generation <strong>of</strong> currency crisis models (Krugman 1979,<br />

Flood and Garber 1984) emphasized the inconsistency between financing a budget deficit<br />

through money creation and trying to maintain a pegged exchange rate regime. Since these<br />

models did not seem to fit the 1992/93 European Exchange Rate Mechanism crises, a second<br />

generation <strong>of</strong> crisis models (Obstfeld 1994) was developed in which an inconsistent policy<br />

stance, combined with self-fulfilling shifts in investor sentiments, could give rise to multiple<br />

equilibria. Yet neither variant could explain the East Asian crises, necessitating a third<br />

generation that incorporated foreign exchange exposure <strong>of</strong> the private financial and corporate<br />

sectors. But this third generation <strong>of</strong> currency crisis models could not explain subsequent<br />

crises, such as Argentina (2002). And while the collapse <strong>of</strong> Argentina’s currency board<br />

1 Prepared for the High Level Seminar on <strong>Crisis</strong> Prevention, Singapore, July 10-11, 2006.<br />

The author is Division Chief, Policy Development and Review Department, <strong>IMF</strong>. The views<br />

expressed in this paper are those <strong>of</strong> the author and should not be attributed to the<br />

International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or its Management.

- 2 -<br />

Figure 1. Selected Macroeconomic Indicators: Mean 1/<br />

12<br />

Real GDP growth<br />

(In percent per year)<br />

40<br />

Inflation<br />

(In percent per year)<br />

9<br />

35<br />

30<br />

6<br />

25<br />

3<br />

20<br />

0<br />

15<br />

-3<br />

10<br />

5<br />

-6<br />

0<br />

-9<br />

t-3 t-2 t-1 t t+1 t+2 t+3<br />

-5<br />

t-3 t-2 t-1 t t+1 t+2 t+3<br />

20<br />

Real exchange rate<br />

(Annual change, in percent)<br />

15<br />

Current account balance<br />

(In percent <strong>of</strong> GDP)<br />

10<br />

10<br />

0<br />

5<br />

-10<br />

0<br />

-20<br />

-5<br />

-30<br />

t-3 t-2 t-1 t t+1 t+2 t+3<br />

-10<br />

t-3 t-2 t-1 t t+1 t+2 t+3<br />

Sources: International Monetary Fund; WEO database, and <strong>IMF</strong> staff estimates.<br />

1/ Averages (Mean) are given by the solid lines, with standard deviations around the mean given by the<br />

dotted lines. The sample consists <strong>of</strong> Argentina (1995 and 2002), Brazil (1999), Indonesia (1997), Malaysia<br />

(1997), Mexico (1997), Philippines (1997), Russia (1998), Thailand (1997), Turkey (2000), and Uruguay<br />

(2002).

- 3 -<br />

resulted mainly from a fiscal policy stance that was incompatible with the exchange rate<br />

regime, the crisis was not in the mold <strong>of</strong> the first generation models as the government was<br />

bond financing its deficit in a deflationary, rather than an inflationary, environment. 2<br />

3. All this suggests that understanding capital account crises—surely a prerequisite to<br />

preventing them—requires a more general analytical framework. The central thesis <strong>of</strong> this<br />

paper is that a capital account crisis requires—and is caused by—a combination <strong>of</strong> balance<br />

sheet weaknesses in the economy and a specific crisis trigger. The diversity <strong>of</strong> capital<br />

account crises is therefore not surprising because balance sheet weaknesses can take various<br />

forms, as can the specific factors that trigger the crisis. Much like a bomb that requires both<br />

an explosive material and a detonator to cause an explosion, neither the balance sheet<br />

weakness nor the crisis trigger on its own is likely to cause (as much) mischief. Thus an<br />

economy can live with currency and maturity mismatches in private or public sectoral<br />

balance sheets for years if, serendipitously, nothing triggers a crisis. Yet there are many<br />

possible crisis triggers, both external—contagion, a terms <strong>of</strong> trade shock, a deterioration in<br />

market conditions—and domestic, such as an inconsistent macroeconomic policy stance (see<br />

Table 1 for a summary <strong>of</strong> vulnerabilities and crisis triggers in selected emerging market<br />

countries).<br />

4. Since emerging market countries still typically lack the ability to borrow in their own<br />

currencies (especially at long maturities), some currency and maturity mismatches may be<br />

unavoidable. 3 In the same vein, while sound macroeconomic policies can help avoid certain<br />

crisis triggers, others may be beyond the control <strong>of</strong> the country. Therefore, national<br />

authorities should seek to avoid both balance sheet weaknesses and poor policies in order to<br />

minimize the likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis.<br />

5. The remainder <strong>of</strong> this paper is organized as follows. Drawing on recent work<br />

undertaken at the <strong>IMF</strong>, section II provides a few illustrative examples <strong>of</strong> how interactions<br />

between crisis triggers and underlying balance sheet vulnerabilities resulted in some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

recent capital account crises. 4 Section III draws some general lessons for reducing balance<br />

sheet vulnerabilities. Section IV turns to crisis prevention more generally, including some <strong>of</strong><br />

the possible roles <strong>of</strong> the <strong>IMF</strong>, highlighting measures that have been taken at the Fund since<br />

the mid-1990s in this direction. Section V concludes.<br />

2 See Box 2.1 <strong>of</strong> Roubini and Setser (2005) for a comparison <strong>of</strong> assumptions in different<br />

generations <strong>of</strong> models.<br />

3 Some countries, however, may find it rational to borrow in foreign currencies, given trend<br />

real appreciation <strong>of</strong> their currencies leading to low (or even negative) real interest rates. See<br />

Lipschitz et al. (2005) for a discussion <strong>of</strong> this case.<br />

4 This section draws heavily on Allen et al. (2000), and Rosenberg et al. (2005).

- 4 -<br />

Table 1. Taxonomy <strong>of</strong> Vulnerability and Triggers in Recent <strong>Capital</strong> <strong>Account</strong> Crises<br />

<strong>Crisis</strong> Balance sheet vulnerability <strong>Crisis</strong> trigger<br />

Mexico (1994)<br />

Argentina (1995)<br />

Thailand (1997)<br />

Korea (1997)<br />

Indonesia (1997)<br />

Government's short-term external<br />

(and FX-denominated) liabilities<br />

Banking system short-term<br />

external and peso and FXdenominated<br />

liabilities<br />

Financial and non-financial<br />

corporate sector external<br />

liabilities; concentrated exposure<br />

<strong>of</strong> finance companies to property<br />

sector<br />

Financial sector external<br />

liabilities (with substantial<br />

maturity mismatch) and<br />

concentrated exposure to<br />

chaebols; high corporate<br />

debt/equity ratio<br />

Corporate sector external<br />

liabilities; concentration <strong>of</strong><br />

banking system assets in real<br />

estate/property-related lending;<br />

high corporate debt/equity ratio<br />

Tightening U.S. monetary policy;<br />

political shocks (Chiapas;<br />

assassination <strong>of</strong> the presidential<br />

candidate)<br />

Mexican ("Tequila") crisis<br />

Terms <strong>of</strong> trade deterioration; asset<br />

price deflation.<br />

Terms <strong>of</strong> trade deterioration; falling<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>itability <strong>of</strong> chaebols; contagion<br />

from Thailand's crisis<br />

Contagion from Thailand's crisis;<br />

banking crisis<br />

Russia (1998)<br />

Government's short-term external<br />

financing needs<br />

Failure to implement budget deficit<br />

targets; terms <strong>of</strong> trade deterioration<br />

Brazil (1999)<br />

Government's short-term external<br />

liabilities<br />

Doubts about ability to implement<br />

budget cuts and loose budget proposal<br />

for 1999; current account deficit;<br />

contagion from Russian default<br />

Turkey (2000)<br />

Government short-term<br />

liabilities, banking system FXand<br />

maturity mismatches<br />

Widening current account deficit, real<br />

exchange rate appreciation, terms <strong>of</strong><br />

trade shock; uncertainty about<br />

political will <strong>of</strong> government to<br />

undertake reforms in the financial<br />

sector.<br />

Argentina (2002)<br />

Public and private sector external<br />

and FX-denominated liabilities.<br />

Persistent failure to implement budget<br />

deficit targets; inconsistency between<br />

currency board arrangement and<br />

fiscal policy; Russian default<br />

Uruguay (2002)<br />

Banking system short-term<br />

external liabilities.<br />

Argentine deposit freeze leading to<br />

mass withdrawls from Uruguay

- 5 -<br />

II. BALANCE SHEET VULNERABILITIES AND CRISIS TRIGGERS—SOME ILLUSTRATIVE<br />

EXAMPLES<br />

6. Traditional flow-based analysis focuses on the gradual build up <strong>of</strong> unsustainable<br />

budget and current account deficits. The balance sheet approach (BSA) complements such<br />

analysis by considering how shocks to stocks <strong>of</strong> assets and liabilities in sectoral balance<br />

sheets can lead to large adjustments that are manifested in capital outflows (and<br />

corresponding current account surpluses as external financing is withdrawn).<br />

7. While further disaggregation is possible, BSA typically analyzes four main sectoral<br />

balance sheets: the government sector (including the central bank), the private financial<br />

sector, the private non-financial sector (households and corporations), and the external sector<br />

(or “rest <strong>of</strong> the world”). This sectoral decomposition can reveal important vulnerabilities that<br />

are hidden when considering the country’s consolidated balance sheet (or its net position visà-vis<br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> the world). In particular, weaknesses in one sectoral balance sheet may<br />

interact with others, eventually spilling into a country-wide balance <strong>of</strong> payments crisis even<br />

though the original mismatch was not evident in the country’s aggregate balance sheet. A<br />

prime example is the foreign currency debt between residents, which <strong>of</strong> course gets netted<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the aggregate balance sheet, but may nevertheless contribute to a balance <strong>of</strong> payments<br />

crisis. For example, if the government has foreign currency debt to residents and faces a<br />

funding crisis, it will need to draw down the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves,<br />

possibly leading to a balance <strong>of</strong> payments crisis.<br />

8. More generally, a loss <strong>of</strong> confidence or a re-evaluation <strong>of</strong> risks in one sector can<br />

prompt sudden and large scale portfolio adjustments, such as massive withdrawals <strong>of</strong> bank<br />

deposits, panic sales <strong>of</strong> securities, or abrupt halts in debt rollovers. As the exchange rate,<br />

interest rates, and other prices adjust, other balance sheets can sharply deteriorate, in turn<br />

provoking creditors to shift toward safer foreign assets—resulting in capital outflows and<br />

further pressure on the exchange rate and reserves until there is a full-blown capital account<br />

crisis.<br />

9. The following examples show how weaknesses in sectoral balance sheets—currency<br />

and maturity mismatches, capital structure, and solvency—together with specific “triggers”<br />

resulted in some <strong>of</strong> the recent capital account crises. 5 While there is undoubtedly an element<br />

<strong>of</strong> “ex post rationalization” in identifying the crisis triggers, these examples are nevertheless<br />

useful in illustrating how exposures in different sectoral balance sheets can interact to<br />

produce vulnerabilities.<br />

5 The three examples—Thailand (1997), Argentina (2002), and Turkey (2000/2001)—are<br />

chosen from the list in Table 1 to represent three different sources <strong>of</strong> balance sheet<br />

vulnerabilties.

- 6 -<br />

Thailand (1997)<br />

10. Thailand’s devaluation on July 2, 1997 was the first in a wave <strong>of</strong> capital account<br />

crises that afflicted East Asia, eventually engulfing Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the<br />

Philippines. The macroeconomic consequences for Thailand were pervasive, with real GDP<br />

growth falling from 9 percent in 1994/95 to -11 percent in 1998, the current account<br />

swinging from a deficit <strong>of</strong> 8 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP in 1996 to a surplus <strong>of</strong> 13 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP<br />

in 1998, and external debt rising from 60 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP at end-1996 to 94 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP<br />

by end-1998.<br />

Balance sheet vulnerabilities<br />

11. What were the underlying balance sheet vulnerabilities? Although available data are<br />

incomplete, Table 2 provides a snapshot (as <strong>of</strong> end-1996) <strong>of</strong> the main sectoral liabilities.<br />

Table 2. Thailand: Sectoral Foreign Assets and Liabilities, end-1996<br />

(In billions <strong>of</strong> U.S. dollars)<br />

Assets Liabilities<br />

Net<br />

General government 38.7 5.2 33.5<br />

Short-term 38.7 0.0 38.7<br />

Medium- and long-term 0.0 5.1 -5.1<br />

Commercial banks 7.0 48.1 -41.1<br />

Short-term 2.6 28.2 -25.6<br />

Medium- and long-term 4.4 19.9 -15.5<br />

Domestic FX 0.0 0.0 0.0<br />

Non-banks 0.5 98.0 -97.5<br />

Short-term 0.5 23.6 -23.1<br />

Medium- and long-term 0.0 42.9 -42.9<br />

Domestic FX 0.0 31.5 -31.5<br />

Subtotal<br />

Short-term 41.8 51.8 -10.0<br />

Medium- and long-term and domestic FX 4.4 99.5 -95.0<br />

Total 46.2 151.3 -105.1<br />

Source: Figures 1 and 2 <strong>of</strong> Allen et al. (2002).<br />

• Thailand’s short-term liability position vis-à-vis the rest <strong>of</strong> the world was US$10 billion,<br />

but this masked the huge currency and maturity mismatches <strong>of</strong> the banking and nonfinancial<br />

sectors.<br />

• Short-term net foreign liabilities <strong>of</strong> the banking system were US$25.6 billion (=US$28.2-<br />

US$2.6 billion). Even if some <strong>of</strong> its medium- and long-term assets (US$4.4 billion) could

- 7 -<br />

be made liquid, there remained a potential financing gap <strong>of</strong> US$21 billion if short-term<br />

liabilities could not be rolled over.<br />

• Of the non-bank sector’s total liabilities, some US$66.4 billion was owed to foreigners in<br />

foreign currency (including equity, which would likely be converted into foreign<br />

currency if foreigners withdrew), <strong>of</strong> which US$23.6 billion was short-term.<br />

• Commercial banks were covering their overall (short- and long-term) FX-denominated<br />

liabilities <strong>of</strong> US$48.1 billion 6 with foreign assets <strong>of</strong> US$7.0 billion and FX-denominated<br />

claims on domestic residents <strong>of</strong> US$31.5 billion, leaving a net FX liability position <strong>of</strong><br />

US$9.6 billion. However, this assumed that domestic residents would be able to cover the<br />

US$31.5 billion <strong>of</strong> FX-liabilities in the event <strong>of</strong> a devaluation. The non-financial sector’s<br />

foreign liabilities amounted to US$98 billion (against foreign asset holdings <strong>of</strong> just<br />

US$0.5 billion). Thus, to the extent that the non-financial sector did not have a natural<br />

FX hedge (i.e., were not exporters), the US$31.5 billion <strong>of</strong> FX-risk <strong>of</strong> the banking system<br />

had simply been transformed into credit risk. 7 Compounding this risk was the weak<br />

capital structure <strong>of</strong> the corporate sector in Thailand (and in Asia, more generally), with an<br />

average debt-equity ratio <strong>of</strong> 196.<br />

These mismatches meant that Thailand’s vulnerability to a crisis was far greater than the<br />

US$10 billion aggregate short-term liability position to the rest <strong>of</strong> the world would suggest.<br />

<strong>Crisis</strong> Trigger<br />

12. In the event, the proximate trigger <strong>of</strong> the crisis was the asset price deflation (stock<br />

prices fell by 60 percent between mid-1996 and mid-1997, while inflation-adjusted property<br />

prices fell by 50 percent between end-1991 and end-1997). This called into question the<br />

creditworthiness <strong>of</strong> the non-financial sector and therefore the quality <strong>of</strong> banks’ assets,<br />

including its FX cover. Against a background <strong>of</strong> an unsustainable current account deficit<br />

(which had reached 8 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP in 1996), a significant real exchange rate appreciation,<br />

and a weakening fiscal balance, pressures on the Thai baht increased during 1996 and the<br />

first half <strong>of</strong> 1997. Of the US$38 billion <strong>of</strong> foreign exchange reserves at end-1996, the Bank<br />

<strong>of</strong> Thailand used up some US$7 billion in foreign exchange intervention plus increasing its<br />

FX forward and swap obligations from about US$5 billion to almost US$30 billion.<br />

Information on the counterparties to these <strong>of</strong>f-balance sheet swap operations is not available.<br />

To the extent that these were Thai banks, this would have decreased the (on-balance sheet)<br />

FX exposure <strong>of</strong> the banking system without implying a loss for the country as a whole. But if<br />

they were nonresident entities, this would have meant that the country had only US$3 billion<br />

6 This assumes that all medium-term liabilities to the external sector were denominated in<br />

foreign currency.<br />

7 Writing <strong>of</strong>f the claims <strong>of</strong> the banking sector on the non-financial sector would, obviously,<br />

worsen the balance sheet <strong>of</strong> the former, to US$41 billion.

- 8 -<br />

<strong>of</strong> foreign exchange reserves, plus about US$3 billion <strong>of</strong> banks’ short-term foreign assets, to<br />

cover some US$48 billion <strong>of</strong> short-term liabilities.<br />

Argentina (2002)<br />

13. Weaknesses in Argentina’s public sector balance sheet are well known. In particular,<br />

by end-2001, foreign currency denominated public debt had reached 62 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP, and<br />

gross financing need <strong>of</strong> the government had risen to 14 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP, while the central<br />

bank’s gross foreign assets amounted to less than 5 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP (which was in any case<br />

required for backing the central bank’s domestic monetary liabilities under the convertibility<br />

law). Much less well-known are weaknesses in the private sector’s balance sheets and how<br />

these contributed to the crisis.<br />

Balance sheet vulnerabilities<br />

14. In fact, private sector currency mismatches were severe, with foreign currency debt<br />

larger (in relation to exports) than in the East Asian crisis—notoriously considered to be<br />

“private sector-driven” crises. At end-2000, the Argentine corporate sector had borrowed<br />

some US$37 billion externally as well as US$30 billion from the domestic banking sector—<br />

for a total FX exposure <strong>of</strong> 194 percent <strong>of</strong> exports. 8 In part, this was because domestic banks<br />

had to lend in foreign currency in order to narrow their own FX-exposure arising from<br />

foreign currency deposits. As in Thailand, however, this meant that banks’ FX-risk was<br />

being transformed into credit risk on households and corporations—neither <strong>of</strong> which had<br />

significant natural hedging opportunities as Argentina’s export sector was small, and<br />

households were using the loans for home mortgages.<br />

15. Argentina also lost more reserves in 2001 as a result <strong>of</strong> a bank run than as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

the government’s inability to access external markets for its financing needs. This was<br />

because the relatively long maturity <strong>of</strong> the government’s debt limited the pace at which<br />

international investors could withdraw, while convertibility allowed depositors to withdraw<br />

peso deposits and convert them into dollars. Of course, this run from peso deposits was not<br />

unrelated to the public sector’s funding difficulties—not least because depositors recalled<br />

how previous crises had resulted in deposit freezes (which, indeed, later happened in<br />

the 2002 crisis as well).<br />

16. Table 3 presents a simplified balance sheet <strong>of</strong> the banking sector. The balance sheet<br />

provides two important insights:<br />

• During 2001, domestic deposits and external liabilities fell by some US$24 billion,<br />

requiring the banking system to reduce its lending to the private sector by some<br />

8 By contrast, the corresponding exposure in terms <strong>of</strong> exports was 160 percent in Thailand<br />

and 60 percent in Korea.

- 9 -<br />

US$12 billion, run down liquid assets by US$5 billion, and borrow some US$9 billion<br />

Table 3. Argentina: Principal Assets and Liabilities <strong>of</strong> the Banking System<br />

(in billions <strong>of</strong> U.S. dollars)<br />

End-1998 End-1999 End-2000 End-2001<br />

Principal assets<br />

Cash and liquid assets 8.4 8.4 8.3 3.4<br />

Domestic currency 2.9 2.8 2.5 1.9<br />

Foreign currency and liquid assets 5.5 5.6 5.9 1.5<br />

Loans to and securities issued by the public sector 23.5 28.2 28.7 30.1<br />

Domestic currency 4.8 5.5 3.7 3.4<br />

Foreign currency 18.7 22.7 25.0 26.7<br />

Loans to and securities issued by the private sector 70.5 68.4 65.8 54.2<br />

Domestic currency 26.9 25.9 25.0 15.0<br />

Foreign currency 43.7 42.5 40.9 39.1<br />

Subtotals<br />

Domestic currency assets 34.5 34.1 31.1 20.2<br />

Foreign currency assets 68.0 70.9 71.9 67.4<br />

102.5 105.0 102.9 87.6<br />

Principal liabilities<br />

Deposits 77.3 79.9 83.2 67.3<br />

Domestic currency 37.3 35.8 34.7 21.7<br />

Foreign currency 40.0 44.2 48.5 45.6<br />

External obligations 21.4 22.8 24.1 16.3<br />

Domestic currency 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.1<br />

Foreign currency 20.9 22.2 23.7 16.2<br />

Subtotals<br />

Domestic currency liabilities 37.8 36.3 35.1 21.7<br />

Foreign currency liabilities 60.9 66.4 72.2 61.8<br />

98.7 102.7 107.3 83.5<br />

Central bank support 0.3 0.2 0.1 9.2<br />

Domestic currency 0.3 0.2 0.0 4.1<br />

Foreign currency 1/ ... ... 0.1 5.1<br />

Liabilities, including liabilities to central bank 99.0 103.0 107.5 92.7<br />

Source: Table 4.2 <strong>of</strong> Rosenberg et al. (2005). Central Bank <strong>of</strong> Argentina presentation based<br />

on Lagos (2002).<br />

1/ Data from Lagos (2002). Central Bank <strong>of</strong> Argentina (BCRA) swap obligations disaggregated from other<br />

obligations due to financial intermediation in BCRA data.

- 10 -<br />

from the central bank. Moreover, as domestic currency deposits fell more rapidly than<br />

foreign currency deposits, banks had to reduce their domestic currency-denominated<br />

lending faster than their FX-denominated lending, even though domestic currency loans<br />

were more likely to perform in the event <strong>of</strong> a devaluation, as opposed to FX-denominated<br />

loans, which were likely to turn non-performing. (See Figure 2 for an illustration <strong>of</strong><br />

maturity mismatches, including and excluding domestic foreign currency deposits.)<br />

Figure 2. Argentina: Maturity Mismatches: With and Without<br />

Foreign Currency Deposits, 2001<br />

(in billions <strong>of</strong> U.S. dollars)<br />

Maturity Mismatch in<br />

External Position<br />

32.8<br />

32.8<br />

Maturity Mismatch<br />

in Foreign Currency<br />

(Including Domestic<br />

Foreign Currency<br />

Deposits)<br />

-8.2<br />

-41.0<br />

Liquid assets<br />

Short-term liabilities<br />

Mismatch<br />

-89.5<br />

-56.7<br />

Source: Figure 4.1 <strong>of</strong> Rosenberg et al. (2005). Country authorities and Fund staff<br />

estimates.<br />

• The balance sheet also shows the banking sector’s exposure to the government, with<br />

credit to the private sector representing 28 percent <strong>of</strong> bank’s assets at the end <strong>of</strong> 2000,<br />

and 35 percent <strong>of</strong> its FX-denominated assets. But far from being a source <strong>of</strong> strength to<br />

the banking sector facing a deposit run, the government—facing its own gross financing<br />

needs <strong>of</strong> some US$37 billion—was a source <strong>of</strong> weakness. The government could not<br />

draw on the central bank’s reserves to meet its financing needs, as these were required to<br />

back the central bank’s monetary liabilities, so the government had to turn to banks both<br />

to roll over its maturing debts and to provide additional financing. This meant that banks

- 11 -<br />

could not reduce their exposure to the government to meet the deposit outflow without<br />

triggering a government funding crisis, and instead had to run down their own external<br />

assets—the one asset that would have continued to perform in the event <strong>of</strong> default and<br />

devaluation. Banks also had to reduce their domestic currency lending to the private<br />

sector, though these were more likely to perform in the event <strong>of</strong> a devaluation.<br />

<strong>Crisis</strong> trigger<br />

17. Argentina’s experience illustrates how currency and maturity mismatches in the<br />

public and private sector balance sheets can interact to exacerbate vulnerabilities. But what<br />

triggered the crisis? In contrast to some other capital account crises (e.g., Uruguay) where a<br />

specific event triggered the crisis, Argentina’s 2002 crisis was the culmination <strong>of</strong> a prolonged<br />

period over which it became increasingly apparent that fiscal policy was not consistent with<br />

the pegged exchange rate under the currency board arrangement regime. Traditional currency<br />

crisis models would suggest that if the central bank expands domestic credit at a faster rate<br />

then the growth in money demand, then the exchange rate peg will eventually collapse.<br />

However, this was not the case in Argentina, where the central bank largely remained within<br />

the strictures <strong>of</strong> the currency board regime. Nevertheless, Argentina’s fiscal policy was<br />

intertemporally inconsistent with its exchange rate peg.<br />

18. In particular, the “fiscal theory <strong>of</strong> price determination” emphasizes the intertemporal<br />

budget constraint <strong>of</strong> the consolidated public sector (including the central bank), whereby the<br />

nominal stock <strong>of</strong> liabilities—outstanding government debt and base money stock—deflated<br />

by the price level must equal the present value <strong>of</strong> primary surpluses and seignorage. 9<br />

Assuming that the public sector does not repudiate its obligations (either bonds or base<br />

money), the intertemporal budget constraint must be satisfied. But there are two ways in<br />

which this may happen. In a money dominant regime, the price level is determined, and it is<br />

the stream <strong>of</strong> primary surpluses on the right-hand-side <strong>of</strong> the equation that must adjust to<br />

maintain the government’s solvency. In a fiscal dominant regime, the stream <strong>of</strong> future<br />

primary surpluses is given, and it is the price level that must adjust to ensure that the<br />

government’s present value budget constraint is satisfied.<br />

9 In mathematical terms:<br />

∞<br />

D ( )<br />

t<br />

+ M ⎧ s<br />

t<br />

t+ j<br />

+ θt+<br />

j ⎫<br />

= E<br />

t ⎨∑ j ⎬<br />

(1)<br />

Pt<br />

⎩ j=<br />

0 (1 + r)<br />

⎭<br />

where D t is the nominal stock <strong>of</strong> outstanding government debt inherited at the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

period t, M t is the nominal stock <strong>of</strong> money (net <strong>of</strong> the central bank’s foreign exchange<br />

reserves and credit to the economy) inherited at the beginning <strong>of</strong> period t, P is the price level,<br />

s is the primary surplus and θ is central bank seignorage (in real terms), (1+r) is the<br />

economy’s discount factor, and E{ •}<br />

is the expectations operator.

- 12 -<br />

19. Under a pegged exchange rate, the domestic price level is determined by the<br />

exchange rate (for instance, by purchasing power parity or—more generally—by the<br />

requirement that the exchange rate not become uncompetitive) and cannot, in general, adjust<br />

to satisfy the intertemporal budget constraint. Therefore, to be viable, an exchange rate peg<br />

requires that macroeconomic policies operate under a “money dominant” regime.<br />

Argentina’s 2002 crisis came about as it became increasingly apparent that the country was<br />

in a fiscal dominant regime such that the requisite fiscal surpluses were unlikely to be<br />

generated to satisfy the public sector’s intertemporal budget constraint. 10<br />

Turkey (2000/01)<br />

20. In late-2000 and early 2001, Turkey suffered twin banking and balance <strong>of</strong> payments<br />

crises when it was about ten months into an exchange-rate based disinflation program. The<br />

disinflation program had been intended to tackle the unsustainable public debt dynamics<br />

which had resulted in a public sector borrowing requirement <strong>of</strong> 20 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP (and a<br />

debt ratio <strong>of</strong> 60 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP) with inflation averaging 80 percent during the 1990s.<br />

Balance sheet vulnerabilities<br />

21. A significant share <strong>of</strong> the public debt was in foreign currency or in short-term<br />

domestic currency denominated Treasury bills, partly held by foreign investors. But while<br />

weaknesses <strong>of</strong> the public sector’s balance sheet were well known, the banking system also<br />

had a highly vulnerable balance sheet. First, because <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> high inflation, the<br />

average maturity <strong>of</strong> local currency deposits was short, and half <strong>of</strong> its deposits were in foreign<br />

currency. Second, the public sector’s large borrowing requirements had crowded out the<br />

private sector, with more than half <strong>of</strong> banks’ assets being claims on the public sector<br />

(Figure 3).<br />

22. The state banks’ balance sheets had massive maturity mismatches. Forced to extend<br />

subsidized credits, they accumulated receivables from the government (“duty losses”),<br />

requiring them to borrow heavily at short-term from households and, later in 2000, in the<br />

overnight market to meet their liquidity needs.<br />

23. Meanwhile, private banks were running large currency mismatches for the “carry<br />

trade” <strong>of</strong> borrowing at low cost abroad and investing in high yield local currency government<br />

treasury bills. The pre-announced exchange rate crawl—integral to the disinflation<br />

strategy—provided further incentive for this arbitrage. While there were limits (15 percent <strong>of</strong><br />

capital) on the open FX-position that banks were allowed to run, much <strong>of</strong> the banks’ cover<br />

was in the form <strong>of</strong> forwards with other Turkish banks or claims on domestic residents that<br />

did not have natural hedges. Excluding such cover, the open FX position on the eve <strong>of</strong> the<br />

crisis is estimated to have been some 300 percent <strong>of</strong> bank capital (Figure 4). The initial<br />

10 Indeed, given Brazil’s devaluation in early 1999, the equilibrium price level in Argentina<br />

(at a constant nominal exchange rate) had fallen, making it even more difficult to satisfy the<br />

budget constraint (1) in footnote 9 above.

- 13 -<br />

success <strong>of</strong> the disinflation program in lowering nominal and real interest rates also<br />

encouraged banks to buy longer-term fixed-rate government bonds to “lock-in” the high<br />

interest rates, but as they continued to fund themselves mainly with short-term deposits and<br />

the overnight “repo” market, banks’ maturity mismatch worsened as well.<br />

100<br />

Figure 3. Turkey: Banking Sector Assets<br />

(in percent)<br />

Claims on the government<br />

Claims on the private sector<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002<br />

Source: Figure 4.10 <strong>of</strong> Rosenberg et al. (2005). Country authorities and <strong>IMF</strong> staff<br />

estimates.<br />

24. Overall, therefore, the banking system’s balance sheet was highly vulnerable to an<br />

interest rate or exchange rate shock, as banks were borrowing short-term in foreign currency<br />

and lending in local currency to the government at increasingly long maturities.<br />

Domestically, banks were borrowing short term and also lending at much longer term to the<br />

government. However, given the combined public and banking sector balance sheet<br />

mismatches, policy options were limited. The government could have decreased banks’<br />

currency mismatch by issuing FX-denominated bonds (as it subsequently did) but at the cost<br />

<strong>of</strong> increasing its own currency mismatch. 11 On the other hand, if banks had sought to rapidly<br />

11 During Brazil’s 1999 currency crisis, the government increased its own currency mismatch<br />

to help protect the banking system but had substantial foreign currency reserves that enabled<br />

(continued…)

- 14 -<br />

reduce their currency mismatches either by reducing FX-denominated liabilities or by<br />

acquiring other foreign assets, this would have resulted in higher interest rates which would<br />

not only undermine the government’s debt sustainability but also create losses for banks that<br />

had maturity mismatches.<br />

0<br />

Figure 4. Turkey: Banks' Net Open Foreign Currency<br />

Positions<br />

(in billions <strong>of</strong> U.S. dollars)<br />

-5<br />

-10<br />

-15<br />

Excluding forwards<br />

Including forwards and foreigncurrency-indexed<br />

assets<br />

-20<br />

Jan. 2000 Sep. 2000 Dec. 2000 Mar. 2001 Dec. 2001 Dec. 2002<br />

Source: Figure 4.12 <strong>of</strong> Rosenberg et al. (2005). Country authorities and<br />

<strong>IMF</strong> staff estimates.<br />

<strong>Crisis</strong> trigger<br />

25. The crisis occurred in November 2000 amidst uncertainty about the government’s<br />

will to tackle politically sensitive bank restructurings and against a backdrop <strong>of</strong> a widening<br />

current account deficit (which had reached 7 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP) and a substantial real exchange<br />

rate appreciation as inflationary dynamics—though sharply slowing—outstripped the preannounced<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> crawl. The exodus <strong>of</strong> foreign funds led to a spike in interest rates, which<br />

caused a drop in the value <strong>of</strong> banks’ holdings <strong>of</strong> fixed-rate government bonds as well as<br />

increasing their funding costs. When the peg was abandoned in February 2001—following a<br />

further exodus triggered by a political crisis—banks’ net foreign currency exposure was<br />

revealed. While the fragility <strong>of</strong> the public sector’s balance sheet had contributed to the crisis,<br />

it to do so. The strategy worked in that the economic impact <strong>of</strong> the subsequent devaluation<br />

was one <strong>of</strong> the mildest among capital account crises.

- 15 -<br />

in the aftermath its balance sheet deteriorated significantly. First, the share <strong>of</strong> domestic debt<br />

at floating rates rose as investors demanded protection against further interest rate increases<br />

(and banks sought to reduce the maturity mismatch between short-term deposits and longerterm<br />

government bonds). Second, in an effort to avoid a collapse <strong>of</strong> the banking system, the<br />

government provided a blanket guarantee for banks’ liabilities and issued bonds for their<br />

recapitalization. These bonds increased public debt by 30 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP to almost<br />

90 percent <strong>of</strong> GDP at end-2001.<br />

III. IDENTIFYING BALANCE SHEET VULNERABILITIES<br />

26. The examples above illustrate how currency and maturity mismatches in sectoral<br />

balance sheets, and linkages between them, can contribute to the likelihood that a capital<br />

account crisis could be—and ultimately was—triggered. At the same time, given emerging<br />

market countries’ limited ability to borrow in their own currencies (“original sin”), there<br />

must be FX-exposure in some sectoral balance sheet in the economy. This also means that<br />

any “hedging” will either be incomplete or that, in effect, the country is not a net recipient <strong>of</strong><br />

capital from the rest <strong>of</strong> the world. Therefore, the key to reducing vulnerability is to try to<br />

limit currency, maturity, and capital structure mismatches and ensure that risks—including to<br />

real shocks—are ultimately contained by strong balance sheets within the economy. 12<br />

27. Although balance sheet analysis is still in its infancy, the examples cited above<br />

suggest some conclusions:<br />

• The banking system <strong>of</strong>ten acts as a key transmission channel <strong>of</strong> balance sheet problems<br />

from one sector into another. If a shock in the corporate sector (Asian crisis countries) or<br />

the public sector (Russia 1998, Turkey 2001, Argentina 2002) results in it being unable to<br />

meet its liabilities, then another sector—typically the banking sector—loses its claims. In<br />

turn, this can cause a deposit run, sparking a banking crisis, especially if the<br />

government’s own balance sheet is too weak to provide credible deposit insurance or<br />

lacks international reserves to provide liquidity support in foreign exchange. By the same<br />

token, if banks tighten their lending to prevent their portfolios from deteriorating, then<br />

this further complicates the situation <strong>of</strong> the corporate or public sector that is facing<br />

financing difficulties.<br />

• If the government’s balance sheet is sufficiently strong, it can serve as a “circuit<br />

breaker,” halting the propagation <strong>of</strong> shocks across domestic balance sheets. In a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> recent crises (e.g., Argentina 2002), however, the government balance sheet was the<br />

12 To use an analogy, lightning strikes might leave a house at risk <strong>of</strong> burning down and while<br />

measures can be taken to reduce that risk (e.g., installing a lightning conductor), some risk<br />

may be unavoidable. By purchasing insurance, however, the homeowner transfers the<br />

associated financial risk from his own relatively weak, undiversified balanced sheet to that <strong>of</strong><br />

the insurance company, which is much stronger in that it holds diversified risks.

- 16 -<br />

main source <strong>of</strong> weakness, precluding such a role. Indeed, banks typically want to hold<br />

government securities as they may be the only liquid, domestic-currency denominated<br />

assets. However, if—as in Argentina—the government defaults on its debt, then this can<br />

be a source <strong>of</strong> vulnerability to the banking sector. 13<br />

• Available foreign exchange reserves or contingent financing may be especially valuable<br />

in reducing the economy’s balance sheet vulnerabilities as they can be used to cover<br />

short-term financing needs <strong>of</strong> the public sector, to provide a partial lender <strong>of</strong> last resort<br />

function in dollarized economies, or to help close the private sector’s foreign currency<br />

mismatch—insulating the economy from the impact <strong>of</strong> a devaluation—by providing<br />

liquidity to banks. However for contingent financing to be useful, it must be very quickly<br />

accessible.<br />

• Maturity and currency mismatches are sometimes hidden in indexed or floating rate<br />

instruments. For instance, in Brazil, liabilities may be formally denominated in local<br />

currency but linked to the exchange rate. 14 Likewise, an asset may have a long maturity<br />

but carry a floating interest rate. Such indexation <strong>of</strong>ten creates the same mismatches as if<br />

the debt were denominated in foreign currency or as if the maturity were as short as the<br />

frequency <strong>of</strong> the interest rate adjustments.<br />

• As was the case both in Thailand and in Argentina, balance sheet linkages can transform<br />

one type <strong>of</strong> risk into another without necessarily reducing that risk. For example, the<br />

banking system may try to close its FX mismatch on foreign currency deposits by lending<br />

to domestic corporations in foreign currency. However, if the non-financial sector<br />

recipients <strong>of</strong> those loans do not have natural hedges (e.g., have export revenues), then the<br />

banking system’s currency risk is simply transformed into credit risk.<br />

• Off-balance sheet items can substantially alter the overall risk exposure—reducing or<br />

increasing balance sheet exposures according to whether an underlying position is being<br />

hedged or the entity is taking a speculative position in the derivatives markets. However,<br />

such transactions can also mask vulnerabilities, for instance as risk from a balance sheet<br />

mismatch is transformed into counterparty risk. In aggregate, a sectoral balance sheet<br />

may appear hedged through the derivative markets but may still be exposed to the risk if<br />

13 This suggests that, when the government’s balance sheet is relatively weak, multilateral<br />

organizations could usefully issue debt denominated in emerging market country currencies,<br />

thus providing a domestic-currency denominated asset to the banking sector without the<br />

corresponding default risk. Multilateral organizations would, however, assume the<br />

corresponding currency risk.<br />

14 Over the past couple <strong>of</strong> years, the Brazil government has gradually eliminated much <strong>of</strong> its<br />

foreign currency-indexed debt.

- 17 -<br />

the counterparties are connected. 15 For example, in Turkey, the banking system open FX<br />

exposure was small when forward transactions were included, but the main<br />

counterparties in these forward transactions were other Turkish banks.<br />

• The ultimate buffer for private sector balance sheet mismatches (e.g., currency/FX) is<br />

capital. A major source <strong>of</strong> vulnerability in the East Asian crises was the very high debtequity<br />

ratios (Table 4).<br />

Table 4. Average corporate debt-to-equity ratios in selected countries<br />

(in percent)<br />

Thailand<br />

Taiwan Province<br />

<strong>of</strong> China<br />

United States Germany Malaysia Japan Korea<br />

196 90 106 144 160 194 317<br />

Source: Table 3, Annex II, <strong>of</strong> Allen et al. (2002).<br />

• Pegged exchange rate regimes, by <strong>of</strong>fering an implicit exchange rate guarantee, might<br />

encourage greater risk taking in the form <strong>of</strong> open (mismatched) FX-positions. As noted<br />

above, to the extent that emerging market countries’ ability to borrow in their own<br />

currency is limited, there must be aggregate foreign currency exposure associated with<br />

foreign liabilities (i.e., obligations to non-residents). Nevertheless, there are at least two<br />

ways in which pegged exchange rates might exacerbate foreign currency risk:<br />

• The implicit guarantee might encourage more “carry trade” (arbitrage between<br />

low-cost foreign currency borrowing and higher domestic interest rates at a<br />

given exchange rate) resulting either in greater total foreign borrowing or a<br />

bias towards shorter maturity foreign liabilities (Thailand 1997), Turkey<br />

2001/02).<br />

• Again by providing an implicit exchange rate guarantee, the pegged exchange<br />

rate might encourage more domestic “dollarization”—i.e., holding <strong>of</strong> foreign<br />

currency-denominated assets and liabilities by residents, though neither logic<br />

nor empirical evidence particularly supports this. 16<br />

15 For example, a bank may be closing its spot FX exposure through a derivative transaction<br />

with its parent conglomerate; such practices apparently occurred in Turkey prior to the 2000<br />

crisis.<br />

16 As pointed out in Lessons from the <strong>Crisis</strong> in Argentina (<strong>IMF</strong> Occasional Paper No. 236),<br />

the exchange rate guarantee implicit in a pegged regime (or currency board) cannot<br />

simultaneously explain both asset and liability dollarization. For instance, if the peg is<br />

credible, households may want to borrow in foreign currency (since FX interest rates are<br />

(continued…)

- 18 -<br />

IV. TOWARDS CRISIS PREVENTION<br />

28. The discussion above suggests where balance sheet vulnerabilities might lurk and<br />

how they may interact with specific triggers that result in a full blown crisis. The first step in<br />

crisis prevention is to try to avoid such vulnerabilities—in particular, to ensure that the<br />

government is not (perhaps inadvertently) providing incentives that exacerbate balance sheet<br />

mismatches. It is a truism that sound macroeconomic policies also lessen—but do not<br />

eliminate—the possibility that a crisis will be triggered.<br />

29. What can the Fund do to prevent crises? Surveillance is certainly at the heart <strong>of</strong> any<br />

response in that regard (see Box 1). While Fund-supported programs are usually thought <strong>of</strong><br />

in the context <strong>of</strong> crisis resolution, recent analytical work at the <strong>IMF</strong>—Ramakrishnan and<br />

Zalduendo (2006)—has examined a possible role in the context <strong>of</strong> crisis prevention as well.<br />

30. What factors might determine whether a crisis is triggered? The analysis considers<br />

the experience <strong>of</strong> 27 emerging market countries over the period 1994-04 and identifies 32<br />

episodes <strong>of</strong> “high market pressure” (i.e., when the real exchange rate was depreciating, the<br />

country was losing foreign exchange reserves, or sovereign bond spreads were widening). Of<br />

these 32 episodes, 11 turned into capital account crises while the other 21 did not (Table 5).<br />

31. The intriguing question is why those 11 cases—and not the others—turned into<br />

crises. Part <strong>of</strong> the answer is presumably that the balance sheet vulnerabilities were more<br />

acute in the crisis cases. However, a full comparison between the balance sheet<br />

vulnerabilities in the 32 episodes was beyond the scope <strong>of</strong> the study. 17 Nevertheless, it is<br />

noteworthy that the crisis countries had significantly higher external debt and short-term<br />

debt-to-reserves ratios than the countries that managed to avoid the crisis despite the high<br />

market pressure episode.<br />

typically lower and there is little risk <strong>of</strong> a devaluation) but then they would not want to hold<br />

dollar deposits. Conversely, if there are doubts about the viability <strong>of</strong> the peg, households<br />

would want to hold dollar deposits but not borrow in foreign currency. Empirically, there<br />

does not seem to be any association between pegged exchange rate regimes and dollarization<br />

<strong>of</strong> the banking system.<br />

17 Comparisons across episodes about the susceptibility <strong>of</strong> the country to a crisis are also<br />

difficult because the balance sheet vulnerability typically interacts with a specific crisis<br />

trigger.

- 19 -<br />

Box 1. Surveillance at the <strong>IMF</strong><br />

As described by Lane (2005), greater emphasis in surveillance has been placed on<br />

crisis prevention. Efforts to that end include consideration <strong>of</strong> both stock and flow<br />

imbalances (the former as part <strong>of</strong> the balance sheet approach), better financial sector<br />

surveillance, and a more systematic debt sustainability analysis (DSA). Early warning<br />

<strong>of</strong> possible external imbalances is being attempted through regular vulnerability<br />

exercises, established in 2001, which provide cross-country assessments <strong>of</strong> underlying<br />

weaknesses in economic fundamentals as well as near-term crisis risks. Financial<br />

sector surveillance and adherence to international standards in various areas have been<br />

improved through the use <strong>of</strong> the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP),<br />

integration <strong>of</strong> financial sector issues in the Article IV consultations with member<br />

countries, as well as Reports on Standards and Codes (ROSCs). 18 Additionally, greater<br />

emphasis on transparency, including publication <strong>of</strong> Fund documents and subscription<br />

to the Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS), has facilitated the flow <strong>of</strong> timely<br />

information to the market, perhaps limiting adverse self-fulfilling expectations. Debt<br />

sustainability assessments—required <strong>of</strong> all Article IV consultation reports—provide a<br />

consistency check on baseline medium-term projections, and further identify possible<br />

medium-term vulnerabilities.<br />

18 As highlighted by the McDonough Commission report, further progress could still be<br />

made in this area. The Managing Director’s Medium Term Strategy also puts a premium on<br />

further strengthening the Fund’s financial sector surveillance capabilities.

- 20 -<br />

Table 5. Classification <strong>of</strong> <strong>Capital</strong> <strong>Account</strong> Crises (KAC) and Control Group (CG) Episodes<br />

Episode<br />

Country<br />

Beginning date <strong>of</strong> market<br />

pressure<br />

Identifying Market Pressures 1/<br />

End date <strong>of</strong> market<br />

pressure<br />

Duration <strong>of</strong><br />

pressure in<br />

months 3/<br />

Number <strong>of</strong><br />

months with<br />

pressure<br />

KAC or CG<br />

Episodes 2/<br />

1 Argentina 2001 July 2002 May 11 6 KAC<br />

2 Brazil 1998 August 1999 January 6 3 KAC<br />

3 Bulgaria 1996 May 1996 May 1 1 KAC<br />

4 Ecuador 2000 January 2000 January 1 1 KAC<br />

5 Indonesia 1997 October 1998 January 4 3 KAC<br />

6 Korea 1997 October 1997 December 3 3 KAC<br />

7 Malaysia 1997 July 1998 January 7 5 KAC<br />

8 Russia 1998 August 1998 September 2 2 KAC<br />

9 Thailand 1997 July 1997 August 2 2 KAC<br />

10 Turkey 2000 November 2001 March 5 3 KAC<br />

11 Uruguay 2002 July 2002 July 1 1 KAC<br />

1 Argentina 1998 August 1998 August 1 1 CG<br />

2 Brazil 2002 July 2002 July 1 1 CG<br />

3 Bulgaria 1998 August 1998 August 1 1 CG<br />

4 Chile 1999 June 1999 June 1 1 CG<br />

5 Chile 2002 June 2002 June 1 1 CG<br />

6 Colombia 1998 April 1998 September 6 3 CG<br />

7 Colombia 2002 July 2002 August 2 2 CG<br />

8 Hungary 2003 June 2003 June 1 1 CG<br />

9 Indonesia 2004 January 2004 January 1 1 CG<br />

10 Mexico 1994 December 1995 March 4 3 CG<br />

11 Mexico 1998 August 1998 August 1 1 CG<br />

12 Peru 1998 August 1998 December 5 2 CG<br />

13 Philippines 1997 August 1997 August 1 1 CG<br />

14 Poland 1998 August 1998 August 1 1 CG<br />

15 South Africa 1996 April 1996 April 1 1 CG<br />

16 South Africa 1998 July 1998 July 1 1 CG<br />

17 South Africa 2001 December 2001 December 1 1 CG<br />

18 Turkey 1998 August 1998 August 1 1 CG<br />

19 Venezuela 1994 June 1994 June 1 1 CG<br />

20 Venezuela 1998 August 1998 August 1 1 CG<br />

21 Venezuela 2003 January 2003 January 1 1 CG<br />

Source: Table 1 <strong>of</strong> Ramakrishnan and Zalduendo (2006).<br />

1/ Market pressures identified by classifying monthly data into five clusters based on an index <strong>of</strong> market pressures<br />

that includes changes in REER, FX reserves, and spreads. The listed countries are in the cluster with the highest market pressures.<br />

2/ Private capital flows (net <strong>of</strong> FDI) is used for distinguishing between KAC and CG episodes. A KAC event requires two<br />

quarters <strong>of</strong> either medium outflows or high outflows (as defined by cluster analysis) in the four quarters that follow the<br />

build-up <strong>of</strong> market pressures. All other episodes are in the control group (CG).<br />

3/ Numbers <strong>of</strong> months from the beginning to the end <strong>of</strong> each market pressure episode.<br />

32. Their econometric analysis (discussed in <strong>IMF</strong> 2006) shows that:<br />

• Less flexible exchange rate regimes are associated with a higher likelihood that a market<br />

pressure event turns into a crisis and an overvalued exchange rate (relative to trend) is<br />

significantly associated with a higher likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis.<br />

• Lower external debt (as a percent <strong>of</strong> GDP) is significantly associated with a lower<br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis.

- 21 -<br />

• A higher stock <strong>of</strong> foreign exchange reserves (as a percent <strong>of</strong> reserves) is significantly<br />

associated with a lower likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis.<br />

• Stronger policies—tighter monetary policy or greater fiscal adjustment (particularly in<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> a Fund-supported program)—are significantly associated with a lower<br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis.<br />

• An on-track <strong>IMF</strong>-supported program is associated with a lower likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis, but<br />

the effect is not statistically significant.<br />

• Availability <strong>of</strong> Fund resources is a significant factor in crisis prevention: the larger are<br />

the available Fund resources (as a share <strong>of</strong> short-term debt), the lower is the likelihood <strong>of</strong><br />

a crisis.<br />

33. These results suggest that there is an important liquidity effect <strong>of</strong> Fund support on<br />

crisis prevention since it is the availability <strong>of</strong> Fund resources (disbursements or their<br />

availability for drawing under an on-track precautionary program) that matters, rather than<br />

just an on-track program or possible future drawings under the arrangement.<br />

34. The benefits <strong>of</strong> Fund support go beyond the liquidity effects, however, since the<br />

available Fund financing variable is significant even controlling for the country’s available<br />

foreign exchange reserves. Part <strong>of</strong> the effect must thus arise from a combination <strong>of</strong> stronger<br />

policies (i.e., beyond the fiscal balance and real interest rates included in the regressions)<br />

bolstered by conditionality and in the “seal <strong>of</strong> approval” implicit in Fund disbursements.<br />

Moreover, since the program dummy is not statistically significant, but the Fund financing<br />

variable is strongly significant, the strength and the credibility <strong>of</strong> the Fund’s signal appears to<br />

depend at least to some degree on the extent to which the Fund is willing to put to its own<br />

resources on the line.<br />

35. Finally, it bears emphasizing that the interaction <strong>of</strong> limited currency and maturity<br />

mismatches (low external debt-to-GDP and low short-term debt-to-reserves ratios), strong<br />

policies, and <strong>IMF</strong> financing is critical for crisis prevention. If there are large balance sheet<br />

mismatches and weak policies, not only is there a high probability <strong>of</strong> a crisis, the marginal<br />

impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>IMF</strong> financing on lowering the probability <strong>of</strong> crisis is also small—thus the country<br />

would be highly vulnerable to a crisis (Figure 5).

- 22 -<br />

Figure 5. Marginal Impact <strong>of</strong> Fund Financing, Given Country Fundamentals 1/<br />

Probability<br />

<strong>of</strong> crisis<br />

1.00<br />

0.80<br />

0.60<br />

0.40<br />

Average Fund financing among<br />

KAC episodes<br />

Maximum level <strong>of</strong> Fund financing<br />

among KAC episodes<br />

P(crisis; best<br />

covariates)<br />

P(crisis; median<br />

covariates)<br />

0.20<br />

0.00<br />

0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15<br />

Fund financing<br />

(as share STD)<br />

P(crisis; worst<br />

covariates)<br />

1/ B d i 4 i T bl 2 F d fi i i d fi d h l i di b 12<br />

Source: Figure 7 <strong>of</strong> Ramakrishnan and Zalduendo (2006).<br />

1/ Based on Regression 4 in Table 2 <strong>of</strong> Ramakrishnan and Zalduendo (2006). Fund financing<br />

is defined as cumulative disbursements over 12 months as a share <strong>of</strong> short-term debt. The<br />

figure reflects the probability <strong>of</strong> crisis for different countries based on covariate contributions<br />

at time t-1. Vertical lines are also measured at t-1 and represent, respectively, the average and<br />

maximum level <strong>of</strong> Fund financing among crisis episodes.<br />

V. CONCLUSIONS<br />

36. For most emerging market countries, current market conditions are exceptionally<br />

benign with spreads almost an order <strong>of</strong> magnitude lower than just a few years ago. Yet recent<br />

events have also shown that these countries remain susceptible to shifts in market sentiment.<br />

Therefore, the currently benign conditions should not breed complacency but instead provide<br />

some breathing space for countries to address existing vulnerabilities. 19<br />

37. Most capital account crises appear to have been caused by foreign currency and<br />

maturity mismatches on private or public sector balance sheets coupled with a specific<br />

trigger—domestic or external. Based on the experience <strong>of</strong> these countries, this paper has<br />

sought to identify where and how such balance sheet vulnerabilities might arise.<br />

38. Turning to factors that determine whether a crisis will occur, empirical analysis<br />

suggests that minimizing balance sheet mismatches (a low external debt ratio, a low shortterm<br />

debt-to-reserves ratio), strong macroeconomic policies, and avoiding overvaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

the exchange rate, contribute to reducing the likelihood <strong>of</strong> a crisis. Given that holding foreign<br />

exchange reserves is costly, a particularly interesting result is that <strong>IMF</strong> resources disbursed<br />

(or available under a precautionary program) have an even larger impact on crisis prevention<br />

than the country’s own reserves. This probably reflects a combination <strong>of</strong> stronger policies<br />

19 For example, over the past couple <strong>of</strong> years, Brazil has been reducing the foreign currency<br />

exposure <strong>of</strong> its public sector balance sheet.

- 23 -<br />

under an <strong>IMF</strong>-supported program, the greater credibility <strong>of</strong> the authorities’ policies, and the<br />

stronger signal to markets <strong>of</strong> the <strong>IMF</strong> putting its own resources on the line.

- 24 -<br />

References<br />

Allen, M., et al., 2000, “A Balance Sheet Approach to Financial <strong>Crisis</strong>,” <strong>IMF</strong> Working Paper<br />

No. 02/210 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).<br />

Daseking, C., et al., 2005, Lessons from the <strong>Crisis</strong> in Argentina, <strong>IMF</strong> Occasional Paper<br />

No. 236 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).<br />

Flood, R., and P. Garber, 1984, “Collapsing Exchange-Rate Regimes: Some Linear<br />

Examples,” Journal <strong>of</strong> International Economics, Vol. 17 (August), pp. 1-13.<br />

International Monetary Fund, 2006, Fund Supported Programs and <strong>Crisis</strong> Prevention,<br />

available at http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2006/032306.pdf.<br />

Krugman, P., 1979, “A Model <strong>of</strong> Balance-<strong>of</strong>-Payments Crises,” Journal <strong>of</strong> Money, Credit<br />

and Banking, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 311-25.<br />

Lagos, M., 2002, “The Argentine Banking <strong>Crisis</strong> 2001-2002,” Report prepared for the<br />

Argentine Banking Association.<br />

Lane, P., 2005, “Tensions in the Role <strong>of</strong> the <strong>IMF</strong> and Directions for Reform,” World<br />

Economics, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 1-20.<br />

Lipschitz, L. et al., 2005, “Real Convergence, <strong>Capital</strong> Flows, and Monetary Policy: Notes on<br />

the European Transition Countries,” pp. 61-69 in Schadler, S., ed., Euro Adoption in<br />

Central and Eastern Europe: Challenges and Opportunities (Washington:<br />

International Monetary Fund).<br />

Obstfeld, M., 1994, “The Logic <strong>of</strong> Currency Crises,” Cahiers Economique et Monetaires<br />

No.43, pp. 189-213 (Paris: Banque de France).<br />

Ramakrishnan, U., and J. Zalduendo, 2006, “The Role <strong>of</strong> Fund Support in <strong>Crisis</strong> Prevention,”<br />

<strong>IMF</strong> Working Paper No. 07/75 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).<br />

Rosenberg, C., et al., 2005, Debt-Related Vulnerabilities and Financial Crises, <strong>IMF</strong><br />

Occasional Paper No. 240 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).<br />

Roubini, N., and B. Setser, 2005, Bailouts or Bail-ins? Responding to Financial Crises in<br />

Emerging Economies (Washington: Institute for International Economics).