Download - La Scena Musicale

Download - La Scena Musicale

Download - La Scena Musicale

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

JAZZ<br />

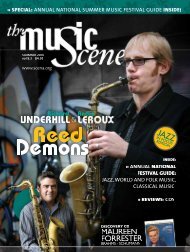

Sonny Rollins<br />

This coming October 29, alto saxophonist<br />

and composer Ornette Coleman will<br />

be making his first Canadian appearance<br />

in 20 some years at Toronto’s hallowed<br />

Massey Hall (the very same site as the legendary<br />

concert with Charlie Parker some 52<br />

years before). <strong>La</strong>st June and July, the equally<br />

legendary tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins<br />

crossed the country during the yearly spate of<br />

national jazz festivals. Coincidentally, both men<br />

have hit the venerable age of 75 this year,<br />

Rollins on September 7, Coleman on March 9.<br />

With long careers behind them, both have<br />

secured their place in the history books, albeit<br />

on very different terms.<br />

Different but similar<br />

While both men are of the same generation, they<br />

belong to very different worlds style-wise.<br />

Rollins, one of the rare surviving masters of the<br />

bop and hard-bop eras, is a champion of the<br />

great American song tradition, a veritable walking<br />

fakebook of evergreens and jazz standards<br />

composed by other greats like Charlie Parker,<br />

Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, as well as a few of<br />

his own (“Oleo,” “Valse Hot” and the perennial<br />

jazz calypso “St Thomas”). Ornette Coleman,<br />

Legends in Our Time<br />

Ornette Coleman - Sonny Rollins<br />

MARC CHÉNARD<br />

conversely, was thrust on the scene amid controversy,<br />

heralded as the instigator of “Free Jazz,”<br />

a term that until its appearance in the late 1950s<br />

meant “music with no cover charge.”<br />

Despite their differences, comparing their<br />

respective careers yields some interesting commonalities.<br />

For starters, each has been rather<br />

shy and withdrawn, taking periodical sabbaticals<br />

from the music and recording business.<br />

Coleman, for one, has gone through so many<br />

stops and starts in his career, releasing records<br />

in short bursts, and spending the rest of his<br />

time away from the studios. In fact, his last disc<br />

to date was a singular duo recording with<br />

German pianist Joachim Kühn, cut in concert in<br />

1996 and released two years later. Rollins, for<br />

his part, dropped out of sight a couple of<br />

times, the first being his legendary bridge period,<br />

where he spent time practicing on the<br />

Williamsburg bridge in New York between 1959<br />

to 1961. From 1966 to 1971, he bowed out<br />

once again, studying Far Eastern philosophies<br />

and religions. In more recent times, he had not<br />

issued an album in about four years before the<br />

newly released Without a Song, the 9-11<br />

Concert, recorded five days after that great<br />

tragedy).<br />

While Rollins’s reputation squarely rests<br />

within the “modern jazz” tradition (i.e. bop and<br />

hardbop), he too was lured to the music of<br />

Coleman at one time. In fact, he put a group<br />

together with two of the latter’s associates,<br />

trumpeter Don Cherry and drummer Billy<br />

Higgins, the main document of that period<br />

being Our Man in Jazz, released by RCA in the<br />

early 1960s. Coleman, in contrast, was really<br />

the first American jazz musician to have broken<br />

the obligatory link between solos and tune<br />

lengths. In other words, if a piece was 32 bars<br />

long, improvised solo chorus had to fall within<br />

that frame and the set harmonies within it.. But<br />

with Coleman, one needed not solo any more<br />

like that, but could play as long as one would<br />

want, with or without any of the underlying<br />

chords. It’s no surprise then that the early period<br />

of the late-1950s-early-1960s (documented<br />

on both the Contemporary and Atlantic<br />

labels) saw him in a pianoless quartet, a context<br />

that liberated musicians from the necessity<br />

of having to listen to a keyboardist’s harmonic<br />

reiterations.<br />

Masters under Scrutiny<br />

As heated as the debate was back then, the<br />

records of that period, including Coleman’s<br />

pioneering double quartet session “Free Jazz”<br />

of late 1961, now make us wonder what all the<br />

fuss was about. But this is yet another example<br />

of how the rifts of yesterday smooth themselves<br />

out over time. Nowadays, even a figure<br />

known for his disparaging of anything remotely<br />

audacious in jazz, one Stanley Crouch, has<br />

come to Coleman’s defence, invoking his link to<br />

the blues and earlier forms jazz.<br />

Ornette Coleman<br />

Like all prominent personalities, both Rollins<br />

and Coleman have had to deal with their fair<br />

share of critical assessments (and broadsides).<br />

Many have seen the former as a larger than life<br />

musical Prometheus who, in spite of his<br />

tremendous gift, had the tendency to underwhelm<br />

his fans (at least in the long string of<br />

studio recordings cut for the Milestone label<br />

over the last thirty years). But he is well aware<br />

of this, though he remains ever the gentleman<br />

about it; in interviews he also expresses selfdoubts<br />

about his abilities, but his motivation<br />

to practice his horn on a daily basis remains.<br />

Coleman has had to endure far more slings<br />

and arrows of outrageous fortune than Rollins,<br />

which has made him a rather relunctant interviewee<br />

over the years. Whether in his early<br />

years, in his resurfacing in the 1970s with his<br />

electrified Prime Time band, and even in his<br />

decision to play with pianists again (not only<br />

Kühn, but also Geri Allen), Coleman has set<br />

himself up to journalistic scrutiny, especially<br />

with respect to his ever diffuse “theory” of<br />

Harmolodics, which still baffles the most astute<br />

of his fans. As such, one could venture to say<br />

that O.C. is one of the very few musicians<br />

today still capable of embodying that “sound<br />

of suprise,” a turn of phrase the prominent<br />

writer Whitney Balliett once coined as his definition<br />

of jazz.<br />

But both musicians are markedly different in<br />

one aspect: in spite of his famous tunes, Rollins<br />

remains a blower at heart (and a very hard one<br />

18 Fall 2005