Picasso Art Article

Picasso Art Article

Picasso Art Article

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

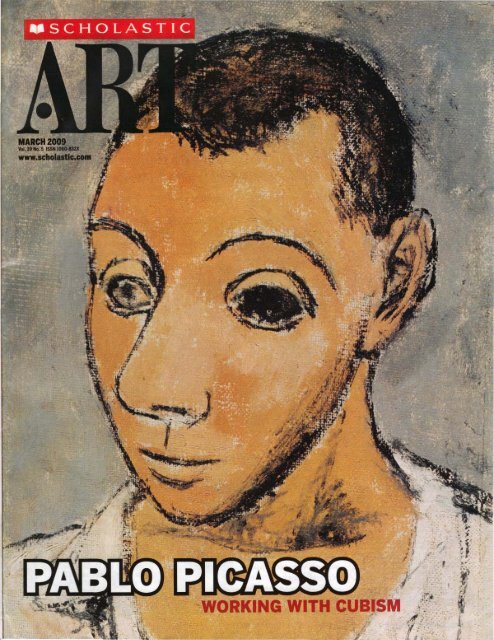

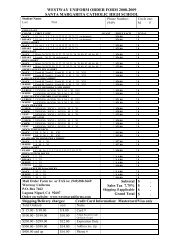

OLASTIC<br />

MARCH 2009<br />

Vol. 39 No. 5 ISSN 1060-S32X<br />

www.scholastic.com<br />

WORKING Wl 'H CUBISM

2 SCHOLASTIC ART* 2009<br />

A NEW ARTIST<br />

FOR A NEW<br />

CENTURY<br />

"The world today doesn't make sense, so why should<br />

I paint pictures that do?" —Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

This self-portrait marks one of <strong>Picasso</strong>'s<br />

early experiments with simplifying the<br />

forms of the face.<br />

Cover: Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> (1881-1973), Self-Portrail. 1906. Oil on canvas<br />

mounted on wood, 10 1/2 x 7 3/4 in. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection,<br />

1998 (1999.363.59). Photo: Malcolm Varon. The Metropolitan Museum<br />

of <strong>Art</strong>, New York, NY, U.S.A. Photo Credit: Image copyright © The Metropolitan<br />

Museum of <strong>Art</strong> / <strong>Art</strong> Resource, NY. © 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> /<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

Maurice R. Robinson, founder of Scholastic Inc., 1895-1982<br />

President. CEO,<br />

Chairman of the Board RICHARD ROBINSON<br />

Editor MARIA RAPOPORT<br />

Contributing Editor DEMISE WILLI<br />

Contributing Editor SUZANNE BILYEU<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Director DEBORAH DINGER<br />

Photo Editor LINDA PATTERSON EGER<br />

Production Editor ALLAN MOLHO<br />

Digital Imager BONNIE ARDITA<br />

Copy Chief RENEEGLASER<br />

Copy Editor VERONICA MAJEROL<br />

President, Class & Library Publishing GREG WORRELL<br />

VP, Editor in Chief, Classroom Mags REBECCA BONDOR<br />

Associate Editorial Director MARGARET HOWLETT<br />

Creative Director, Classroom Mags JUDITH CHRIST-LAFOND<br />

Design Director FELIX BATCUP<br />

Executive Production Director BARBARA SCHWARTZ<br />

Manager Digital Imaging MARC STERN<br />

Exec. Editorial Director, Copy Desk CRAIG MOSKOWITZ<br />

Exec. Director of Photography STEVEN DIAMOND<br />

Director, Manuf. & Distribution MIMI ESGUERRA<br />

Editorial Systems Director DAVID HENDRICKSON<br />

VP, Marketing JOCELYN FORMAN<br />

Marketing Manager ALLICIA CLARK<br />

SCHOLASTIC ART ADVISORY BOARD:<br />

Lana Beverlin, Trenton High School, Trenton, Missouri • Ruth Dexheimer,<br />

Madison Street Academy of Visual and Performing <strong>Art</strong>s, Ocala, Florida •<br />

Judy Leshner, Buena Regional High School, Buena, New Jersey • Carol<br />

Little, Charles R Patton Middle School. Kennett Square, Pennsylvania •<br />

Lydia Narkiewicz, Pioneer High Schoof, Whittier, California • Sue Rothermel.<br />

Wynford Middle School, Bucyrus, Ohio<br />

POSTAL INFORMATION<br />

Scholastic <strong>Art</strong> • (ISSN 1060-832X; In Canada, 2-c no. S5867) is published<br />

six times during the school year, Sept./Oct., Nov., Oec./Jan.. Feb., Mar.,<br />

Apr/May, by Scholastic Inc. Office of Publication: 2931E. McCarty Street,<br />

P.O. Box 3710. Jefferson City, MO 65102-3710. Periodical postage paid<br />

it Jefferson City, MO 65101 and at additional offices. Postmasters: Send<br />

notice of address changes to SCHOLASTIC ART, 2931 East McCarty St.,<br />

P.O. Box 3710, Jefferson City, MO 65102-3710.<br />

PUBLISHING INFORMATION<br />

U.S. prices: $8.95 each per school year, for 10 or more subscriptions<br />

lo the same address. 1-9 subscriptions, each: $19.95 student, $34.95<br />

Teacher's Edition, per school year. Single copy: $5.50 student, $6.50<br />

Teacher's. (For Canadian pricing, write our Canadian office, address below.)<br />

Subscription communications should be addressed to SCHOLASTIC<br />

ART, Scholastic Inc., 333 Randall Rd. Suite 130, St. Charles, IL 60174 or by<br />

calling 1-800-387-1437 ext 99. Communications relating to editorial matter<br />

should be addressed to Maria Rapoport, SCHOLASTIC ART, 557 Broadway,<br />

New York. NY 10012-3999. <strong>Art</strong>@Scholastic.com. Canadian address: Scholastic<br />

Canada Ltd., 175 Hillmount Rd., Markham, Ontario L6C1Z7. Canada<br />

Customer Service: 1-888-752-4690. © 2009 by Scholastic Inc. All Rights<br />

Reserved. Material in this issue may not be reproduced in whole or in part<br />

In any form or format without special permission from the publisher.<br />

SCHOLASTIC, SCHOLASTIC ART, and associated designs are trademarks/<br />

registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc.<br />

Printed in U.S.A.<br />

W! page with the painting below<br />

hen you compare the drawing<br />

on the top of the opposite<br />

it, it's hard to believe that they were created<br />

by the same artist. Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

made the pastel drawing in 1896,<br />

when he was 15. It is a highly<br />

traditional, realistic portrait of his<br />

mother seen in profile.<br />

The painting below it, a head<br />

study, barely registers as a human<br />

face. It is simplified and abstracted,<br />

with shifting viewpoints. Staring<br />

eyes shown from a frontal view loom<br />

over a nose, mouth, and chin shown<br />

from the side and facing in opposite<br />

directions. By 1971, when this work<br />

was created, Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> was the<br />

most famous artist in the world, and<br />

his work had revolutionized art.<br />

A "Why should the Born in 1881 in Malaga, Spain, <strong>Picasso</strong> grew up in a<br />

artist persist in treating modern age full of new ideas and theories. In 1899, Sigmund<br />

Freud, the father of psychology, began publishing<br />

subjects that can be<br />

established so clearly<br />

with the lens of a camera?"<br />

-Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> mind. Six years later, Albert Einstein's scientific theo-<br />

books that opened up the hidden world of the human<br />

Photograph of <strong>Picasso</strong> with ^Aficionado. ries revolutionized our understanding of time and space.<br />

Sorgues, 1912. DP 22; AP PH 2861. Photo:<br />

Coursaget. Musee <strong>Picasso</strong>, Paris, France. Each man in his own way seemed to be saying that reality<br />

looks different from different points of view.<br />

Reunion des Musees Nationaux / <strong>Art</strong> Resource,<br />

NY. © 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

/ <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

At the same time, new technologies were making<br />

painters question the point of realistic art. Why paint what you see when you<br />

can reproduce it more easily with a photograph or<br />

movie? What could painting offer that photography<br />

could not?<br />

While the art world was searching for answers<br />

to these questions, <strong>Picasso</strong> was learning the techniques<br />

of traditional drawing and painting. An un-<br />

> "Who sees the human face<br />

correctly: the photographer,<br />

the mirror, or the painter?"<br />

-Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

Head, Sunday, 1971 (October 3). Oil on canvas, 73 x 60<br />

cm. Musee <strong>Picasso</strong>, Paris / The Bridgeman <strong>Art</strong> Library.<br />

19 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society<br />

(ARS), New York.

»• <strong>Picasso</strong> drew this pastel<br />

portrait of his mother when<br />

he was 15.<br />

Maria <strong>Picasso</strong> Lope* the <strong>Art</strong>ists Mater, 1896.<br />

Pastel on paper. Museu <strong>Picasso</strong>, Barcelona. Spain.<br />

Photo Credit: Bridgeman-Giraudor / <strong>Art</strong> Resource.<br />

NY. © 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights<br />

Society (ARS), Ne» Yoik.<br />

usually gifted child, Pablo could<br />

draw even before he could walk<br />

or talk. His father, Don Jose,<br />

was a painter who created realistic,<br />

decorative works. By the<br />

time Pablo was 9, he was painting<br />

alongside his father. One day, Pablo finished a painting<br />

so perfectly that Don Jose handed over his brushes<br />

and swore never to paint again.<br />

But Don Jose continued to teach. In 1895 he moved his<br />

family to Barcelona so that he could teach at the Academy<br />

of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s. At 14, Pablo was considered too young for<br />

the Academy but was allowed to take the entrance exam,<br />

a series of difficult exercises that took most applicants a<br />

month to complete. Pablo completed them in one day—<br />

astonishing the professors—and was admitted.<br />

Around this time, Pablo drew the pastel portrait of<br />

his mother, Maria (right), in the traditional style taught<br />

at the Academy. In this portrait, <strong>Picasso</strong> uses modeling<br />

and shading to create the illusion of form. He creates<br />

realistic color and a range of shadows, mid-tones, and<br />

highlights by blending dark and light-colored pastels.<br />

The billowy, organic shapes of the figure make it seem<br />

soft and comforting.<br />

In spite of his gifts, or maybe because of them, Pablo<br />

became bored with the rigid rules of the academy and<br />

looked for ways to broaden his horizons. Soon he would<br />

get his chance.<br />

The year was 1900, the start of a new century, and<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> was 19. He had traveled to Paris to show a painting<br />

at the World's Fair, a giant exhibition where 50 million<br />

visitors flocked to see the latest achievements in<br />

technology and culture from all over the world. There,<br />

for the first time, visitors could watch a movie and hear<br />

the actors speak instead of having to read the dialogue on<br />

the screen. They could take a virtual balloon ride, watch<br />

the sky through a giant telescope, and stroll through a<br />

massive exhibition hall where <strong>Picasso</strong>'s work hung among<br />

more than 5,000 paintings from 29 countries.<br />

Filled with curiosity, <strong>Picasso</strong> eagerly took in all the city<br />

had to offer. He combed through museums and galleries<br />

to study Impressionist paintings, Egyptian art, and Japanese<br />

prints. He frequented the city's cafes and nightclubs,<br />

where artists and intellectuals gathered to share ideas.<br />

When <strong>Picasso</strong> finally moved to Paris, his passion for<br />

learning and discovery helped him build the foundation<br />

for his own revolution in art.<br />

MARCH 2009 • SCHOLASTIC ART 3

T<br />

_<br />

HE CUBIST<br />

REVOLUTION<br />

"I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them." —Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

When <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

moved to Paris<br />

in 1904, he was<br />

already well known and<br />

respected for his painting,<br />

drawing, graphic art, and<br />

sculpture. But he felt stifled<br />

by traditional realism. He<br />

wanted more freedom, and<br />

a more imaginative way to<br />

express himself.<br />

In the self-portrait on the<br />

cover, <strong>Picasso</strong> experiments<br />

with heavy black lines, using<br />

them to outline the forms<br />

of his face. But it was not<br />

until 1907, when he visited<br />

a museum of non-Western<br />

art in Paris, that he found<br />

the inspiration that led him<br />

to invent Cubism.<br />

It was there that he first<br />

saw African masks like the<br />

one on page 10. He was<br />

fascinated with the way<br />

these masks simplified forms<br />

and divided them into flat<br />

planes. The masks also<br />

showed <strong>Picasso</strong> a fresh way<br />

to think about art. Instead of<br />

trying to create realistic copies<br />

of faces, the artists who<br />

made these masks interpreted<br />

what they saw. They distorted facial features to express<br />

emotions and qualities like humor or fierceness. <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

called African art an "art of reason" because he thought<br />

African artists depicted not what they saw, but what they<br />

thought and felt.<br />

African masks had an immediate influence on <strong>Picasso</strong>'s<br />

work. He too wanted to make art that showed what<br />

A SCHOLASTIC ART* 2009<br />

he saw not with his eyes but<br />

with his mind. In the study of<br />

a woman's head seen above,<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> has simplified the<br />

complex structure of a woman's<br />

face into basic geometric<br />

forms. Her face has become<br />

A In what ways does this<br />

woman's face resemble the<br />

African mask on page 10?<br />

Bust of a Woman: Study lor Demoiselles D'Avignon,<br />

France, 1907. Oil on canvas, .660 m x .590 m. Musee<br />

National d'<strong>Art</strong> Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou,<br />

Paris, France. Photo Credit: CNAC / MNAM / Dist.<br />

Reunion des Musees Nationaux / <strong>Art</strong> Resource, NY. ©<br />

2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society<br />

(ARS), New York.

« "Are we to paint what's on the face,<br />

what's inside the face, or what's behind it?"<br />

-Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

Man with a Violin, 1911-1912. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 2813/16 in. The Louise and Walter<br />

Arensberg Collection, 1950. Philadelphia Museum of <strong>Art</strong>, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.<br />

Photo Credit: The Philadelphia Museum of <strong>Art</strong> / <strong>Art</strong> Resource, NY. (9 2009 Estate of Pablo<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

made out: an ear seen from the side,<br />

a mouth seen from the front, and a violin<br />

seen from different angles. Other<br />

elements could represent a chin, nose,<br />

or eyes seen from many points of view.<br />

He limited his palette to dark, dull colors<br />

to focus the viewer's attention on<br />

the shapes and composition.<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> worked in this style for several<br />

years. But he eventually realized<br />

that his subjects were becoming overanalyzed,<br />

his compositions too complex,<br />

and all of his paintings were beginning<br />

to look the same. He then began to<br />

paste fragments of real objects onto his<br />

paintings and drawings—scraps of wallpaper,<br />

old postcards, even sprinklings<br />

of sand. Man With a Hat (below) has a<br />

refreshingly childlike quality. Made with<br />

simple shapes cut from colored paper<br />

and scraps of newspaper, it was <strong>Picasso</strong>'s<br />

next new contribution to art—one<br />

of the first collages ever created.<br />

an oval, and her nose has become a triangle that juts out<br />

much like the nose of the African mask on page 10.<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong>'s next step went beyond simplification. Traditional<br />

art shows its subjects from a single point of view.<br />

An artist drawing a model in profile knows the model has<br />

two ears, even though only one ear is visible. With Cubism,<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> sought to create art that depicted objects as<br />

he knew them to be, showing all of their sides at once.<br />

To do this, he combined fragments of different points<br />

of view into a single image.<br />

In Man With a Violin (above), <strong>Picasso</strong> painted a jumble<br />

of overlapping, translucent planes that he tilted and<br />

shifted to make them intersect at random angles. The<br />

subject is almost unrecognizable, but a few details can be<br />

»> Working<br />

with collage<br />

allowed <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

to quickly test<br />

different compositions<br />

by<br />

shifting paper<br />

around.<br />

Man mf/i a Hat, after<br />

December 3,1912. Pasted<br />

paper, charcoal and ink on<br />

paper, 241/2 x 18 5/8 in.<br />

Purchase. (274.1937) The<br />

Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong>, New<br />

York. NY, USA Photo Credit<br />

Digital Image (c) The Museum<br />

of Modem <strong>Art</strong> / Licensed by<br />

SCALA / <strong>Art</strong> Resource, NY.<br />

® 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

/ <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society<br />

(ARS). New York.<br />

MARCH 2009 • SCHOLASTIC ART 5

CUBISM COMES<br />

FULL CIRCLE<br />

"You can try anything in painting.<br />

You even have a right to, provided you never do it again." —Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> became fascinated with dance and theater<br />

in 1917, when he was invited to design sets and<br />

costumes for the Ballet Russes (ba-LEY roos)—the<br />

most important dance company of the day. <strong>Picasso</strong> hated<br />

being tied down to any one style. Working in another<br />

medium gave him a chance to experiment with new<br />

techniques. Collage had also opened up a world of new<br />

possibilities. The flatness of the cut-out shapes inspired<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> to simplify his compostions. The bright colors and<br />

patterns of different kinds of paper inspired him to rein-<br />

troduce color and pattern into his paintings.<br />

Pierrot and Harlequin (pye-RO and HAR-luh-quin)<br />

(pages 8—9), which <strong>Picasso</strong> painted in 1920, and Three<br />

Musicians (left), painted in 1921, show the influence of<br />

working with both the Ballet Russes and collage. In both<br />

paintings, Pierrot and Harlequin, traditional theater characters,<br />

are seen from a frontal point of view and placed<br />

in spaces that resemble a shallow stage set. Like <strong>Picasso</strong>'s<br />

collages, these paintings have no modeling, perspective,<br />

or depth. They are simpler and more colorful than Pica-<br />

A "You work with few colors. But they seem<br />

like a lot more when each one is in the right<br />

place." -Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

Three Musicians, Fontainebleau, summer 1921. Oil on canvas, 6' 7" x 7' 3 3/4". Mrs, Simon<br />

Guggenheim Fund. (55.1949) The Museum ol Modern <strong>Art</strong>, New York, NY, U.S.A. Photo<br />

Credit: Digital Image ©The Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong>/Licensed by SCALA / <strong>Art</strong> Resource, NY.<br />

© 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

K "Different motives inevitably require different<br />

methods of expression." -Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong><br />

Weeping Woman [Femme en pleursj, 1937. Oil on canvas. 60.8 x 50.0 cm., Tate Gallery,<br />

London, Great Britain. Photo Credit: Tate, London / <strong>Art</strong> Resource, NY. © 2009 Estate of<br />

Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

6 SCHOLASTIC ART • 2009

•4 What Cubist elements can you find in this 1969 work?<br />

G'sa! Heads, March 16,1969. Oil on canvas, 194.5 x 129 cm., The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg,<br />

Russia / The Bridgeman <strong>Art</strong> Library. ® 2009 Estate of Pablo <strong>Picasso</strong> / <strong>Art</strong>ists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

sso's earlier Cubist paintings. In them, flat, solid shapes<br />

interlock like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, and broad<br />

organic curves produce a sense of movement.<br />

In Three \iusicians, Pierrot holds a wind instrument,<br />

while Harlequin holds a guitar and a third character, a<br />

bearded monk, holds a piece of sheet music. The musicians'<br />

distorted bodies give them distinct personalities.<br />

The interaction between positive shapes and negative<br />

space creates a sense of visual rhythm that hints at the<br />

musical rhythm of the song the musicians are playing.<br />

Throughout his life, which spanned nearly a century until<br />

his death in 1973, <strong>Picasso</strong> never stopped creating art or looking<br />

for new ways to express himself. His work also reflected<br />

the troubled times he lived in. In 1936, a civil war broke out<br />

in Spain between the Spanish Republican government and<br />

forces led by General Francisco Franco. Franco's forces were<br />

supported by the brutal German dictator Adolf Hitler and<br />

his Nazi Party. In 1937, German planes flew over<br />

the Spanish city of Guernica (GWAIR-ni-kuh).<br />

For three hours they released bombs over the city,<br />

killing between 250 and 1,600 civilians and reducing<br />

the buildings to rubble.<br />

That year, <strong>Picasso</strong> painted Weeping Woman<br />

(opposite page, right), a work that reflects his<br />

sorrow over the horrors of the Spanish Civil<br />

War. The painting combines Cubist elements,<br />

like multiple viewpoints with the distortions<br />

used in Three Musicians. Angular shapes,<br />

clashing color opposites (yellow/purple, red/<br />

green) and repeated, slashing brushstrokes<br />

create a sense of unrest and emotional anguish.<br />

In 1939, General Franco's victory in Spain<br />

gave Hitler the confidence to invade Poland,<br />

an invasion that started World War II (1939-<br />

1945). <strong>Picasso</strong> was living in Paris during the<br />

Spanish Civil War, so his life had not been directly<br />

affected by it. But in 1940, the Germans<br />

invaded Paris and controlled it until 1944.<br />

The Nazis made these four years very hard<br />

for <strong>Picasso</strong>. They considered him an enemy<br />

because he made art that denounced Hitler.<br />

Nazi officers sometimes came to <strong>Picasso</strong>'s studio<br />

to question him. One of them searched the studio<br />

and found a photograph of Guernica taken<br />

after the German bombing. "Did you do this?"<br />

he asked. "No," <strong>Picasso</strong> answered, "you did."<br />

In 1944, when American, British, and<br />

Russian forces liberated Paris, the sounds of their gunfights<br />

with Nazi soldiers rang through the streets surrounding<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong>'s studio. <strong>Picasso</strong> continued to paint<br />

during these battles, singing to himself to drown out<br />

the noise. Through the turmoil of war and until the<br />

end of his life, he never stopped making art.<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong> painted Great Heads (top) when he was in<br />

his late 80s. This work shows Cubist influence: both heads<br />

are seen simultaneously from frontal and profile points<br />

of view. But <strong>Picasso</strong> has applied paint by dripping or<br />

squirting it onto the canvas, or by using his brush to lay<br />

down paint in thick layers and loose strokes. Jagged lines<br />

contrast with swirling lines. Shapes overlap and dissolve.<br />

All of these techniques were invented by a new generation<br />

of artists who had been inspired by <strong>Picasso</strong>'s experiments.<br />

<strong>Picasso</strong>, in turn, experimented with techniques invented<br />

by these artists. The Cubist revolution had come full circle.<br />

MARCH 2009 • SCHOLASTIC ART 7