Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2<br />

Basking sharks were once<br />

hunted widely around<br />

<strong>Scotland</strong>, but since 1998<br />

they’ve been a protected<br />

species. Now, researchers have<br />

found two ‘hotspots’ <strong>of</strong>f <strong>Scotland</strong>’s<br />

west coast that are highly important<br />

for the sharks, as Colin Speedie<br />

reports<br />

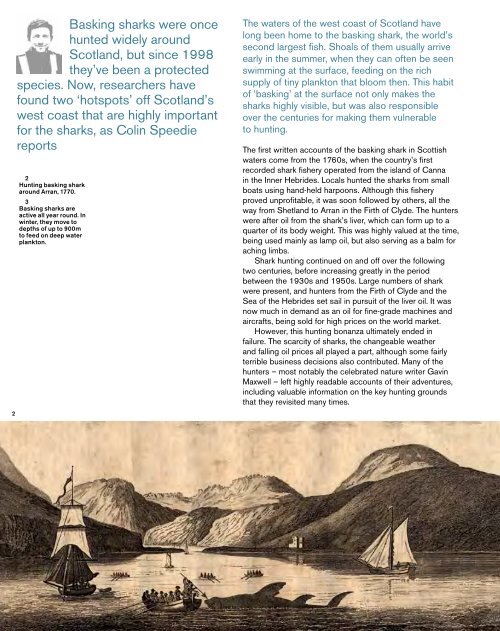

2<br />

Hunting basking shark<br />

around Arran, 1770.<br />

3<br />

Basking sharks are<br />

active all year round. In<br />

winter, they move to<br />

depths <strong>of</strong> up to 900m<br />

to feed on deep water<br />

plankton.<br />

<strong>The</strong> waters <strong>of</strong> the west coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scotland</strong> have<br />

long been home to the basking shark, the world’s<br />

second largest fish. Shoals <strong>of</strong> them usually arrive<br />

early in the summer, when they can <strong>of</strong>ten be seen<br />

swimming at the surface, feeding on the rich<br />

supply <strong>of</strong> tiny plankton that bloom then. This habit<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘basking’ at the surface not only makes the<br />

sharks highly visible, but was also responsible<br />

over the centuries for making them vulnerable<br />

to hunting.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first written accounts <strong>of</strong> the basking shark in Scottish<br />

waters come from the 1760s, when the country’s first<br />

recorded shark fishery operated from the island <strong>of</strong> Canna<br />

in the Inner Hebrides. Locals hunted the sharks from small<br />

boats using hand-held harpoons. Although this fishery<br />

proved unpr<strong>of</strong>itable, it was soon followed by others, all the<br />

way from Shetland to Arran in the Firth <strong>of</strong> Clyde. <strong>The</strong> hunters<br />

were after oil from the shark’s liver, which can form up to a<br />

quarter <strong>of</strong> its body weight. This was highly valued at the time,<br />

being used mainly as lamp oil, but also serving as a balm for<br />

aching limbs.<br />

Shark hunting continued on and <strong>of</strong>f over the following<br />

two centuries, before increasing greatly in the period<br />

between the 1930s and 1950s. Large numbers <strong>of</strong> shark<br />

were present, and hunters from the Firth <strong>of</strong> Clyde and the<br />

Sea <strong>of</strong> the Hebrides set sail in pursuit <strong>of</strong> the liver oil. It was<br />

now much in demand as an oil for fine-grade machines and<br />

aircrafts, being sold for high prices on the world market.<br />

However, this hunting bonanza ultimately ended in<br />

failure. <strong>The</strong> scarcity <strong>of</strong> sharks, the changeable weather<br />

and falling oil prices all played a part, although some fairly<br />

terrible business decisions also contributed. Many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

hunters – most notably the celebrated nature writer Gavin<br />

Maxwell – left highly readable accounts <strong>of</strong> their adventures,<br />

including valuable information on the key hunting grounds<br />

that they revisited many times.<br />

52 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Nature</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scotland</strong>