Eva Gerharz: âThe Construction of Identities: The Case of the Chitta ...

Eva Gerharz: âThe Construction of Identities: The Case of the Chitta ...

Eva Gerharz: âThe Construction of Identities: The Case of the Chitta ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

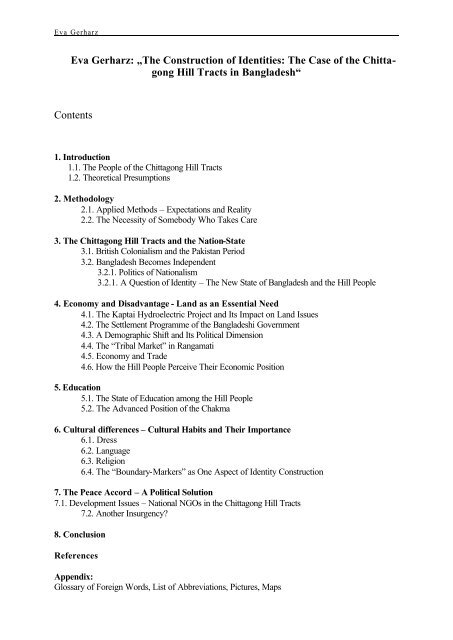

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong>: „<strong>The</strong> <strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong<br />

Hill Tracts in Bangladesh“<br />

Contents<br />

1. Introduction<br />

1.1. <strong>The</strong> People <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

1.2. <strong>The</strong>oretical Presumptions<br />

2. Methodology<br />

2.1. Applied Methods – Expectations and Reality<br />

2.2. <strong>The</strong> Necessity <strong>of</strong> Somebody Who Takes Care<br />

3. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts and <strong>the</strong> Nation-State<br />

3.1. British Colonialism and <strong>the</strong> Pakistan Period<br />

3.2. Bangladesh Becomes Independent<br />

3.2.1. Politics <strong>of</strong> Nationalism<br />

3.2.1. A Question <strong>of</strong> Identity – <strong>The</strong> New State <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh and <strong>the</strong> Hill People<br />

4. Economy and Disadvantage - Land as an Essential Need<br />

4.1. <strong>The</strong> Kaptai Hydroelectric Project and Its Impact on Land Issues<br />

4.2. <strong>The</strong> Settlement Programme <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi Government<br />

4.3. A Demographic Shift and Its Political Dimension<br />

4.4. <strong>The</strong> “Tribal Market” in Rangamati<br />

4.5. Economy and Trade<br />

4.6. How <strong>the</strong> Hill People Perceive <strong>The</strong>ir Economic Position<br />

5. Education<br />

5.1. <strong>The</strong> State <strong>of</strong> Education among <strong>the</strong> Hill People<br />

5.2. <strong>The</strong> Advanced Position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chakma<br />

6. Cultural differences – Cultural Habits and <strong>The</strong>ir Importance<br />

6.1. Dress<br />

6.2. Language<br />

6.3. Religion<br />

6.4. <strong>The</strong> “Boundary-Markers” as One Aspect <strong>of</strong> Identity <strong>Construction</strong><br />

7. <strong>The</strong> Peace Accord – A Political Solution<br />

7.1. Development Issues – National NGOs in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

7.2. Ano<strong>the</strong>r Insurgency?<br />

8. Conclusion<br />

References<br />

Appendix:<br />

Glossary <strong>of</strong> Foreign Words, List <strong>of</strong> Abbreviations, Pictures, Maps

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

1. Introduction – Bangladesh and Its Minorities<br />

Bangladesh is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most homogeneous states as regards ethnic and religious differences.<br />

<strong>The</strong> vast majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population (86.7%) are Muslims, 12.1% Hindus and <strong>the</strong> rest, 1.2%<br />

are Buddhists, Christians and Animists. Those who are non-Muslims live in different communities<br />

spread all over <strong>the</strong> country. As <strong>the</strong> Hindus are chiefly counted as Bengalis, a very little<br />

minority belongs to those entitled as “ethnic communities” (Khaleque 1995, 9) or “tribals” 1 .<br />

How many groups <strong>the</strong>re actually are, is controversially discussed in <strong>the</strong> literature and varies<br />

between 12 and 46. According to <strong>the</strong> 1991 census <strong>the</strong>re are 29 different ethnic groups living<br />

in Bangladesh, but even <strong>the</strong> census, which is carried out every 10 years, is disputed, as some<br />

groups are mentioned twice with different names while o<strong>the</strong>rs are left out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> scheme.<br />

Leaving out <strong>the</strong> clarification <strong>of</strong> that question, approximately 1.2 Million Bangladeshis belong<br />

to <strong>the</strong>se groups according to <strong>the</strong> 1991 census (Khaleque 1995).<br />

<strong>The</strong> different communities vary broadly besides in religious, linguistic and cultural features,<br />

in <strong>the</strong> grade <strong>of</strong> acculturation and resistance. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts (CHT) and its inhabitants<br />

can considered to be extraordinary in respect to historical developments and present<br />

political affiliations 2 . <strong>The</strong> indigenous population <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHT is estimated at approximately<br />

530,000 3 , that is 0,45% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whole population More than 20 years <strong>of</strong> armed resistance have<br />

led <strong>the</strong> CHT to get special attention in Bangladesh as well as across its borders in comparison<br />

to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r indigenous groups in Mymensingh, Jamalpur and Sylhet 4 .<br />

1.1. <strong>The</strong> People <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

Geographically <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts are located in <strong>the</strong> south-east <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh, next to<br />

<strong>the</strong> border <strong>of</strong> Myanmar and <strong>the</strong> Indian states Tripura and Mizoram. <strong>The</strong> total land area comprises<br />

about 12,181 square kilometres and constitutes about 10% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total area <strong>of</strong><br />

Bangladesh (Ahsan, 1989, 961). <strong>The</strong> landscape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts is amazing, with<br />

its comparatively small hills covered by jungles and jhum 5 , while <strong>the</strong> fertile valleys look a<br />

1 This term has been preferably used by <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshis, for ascription as well as self-ascription. Having in<br />

mind <strong>the</strong> negative connotation <strong>of</strong> that term related to “tribalism”, I will try to avoid its usage if possible. Preferred<br />

comp arable terms are “Hill People”, “indigenous”, “jhumma” or “peoples”<br />

2 Although resistance and rebellion have happened among <strong>the</strong> Garo for example (Khaleque 1995). It is not my<br />

intention to marginalise <strong>the</strong>se, but <strong>the</strong> CHT case has gained most attention in <strong>the</strong> recent in national politics as<br />

well as regarding international recognition<br />

3 Numbers from <strong>the</strong> Statistical Pocketbook Bangladesh 98<br />

4 For <strong>the</strong> spatial distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> different indigenous groups see Khaleque (1995, 13).<br />

5 Jhum means shifting cultivation. <strong>The</strong> term also relates to <strong>the</strong> fields in which this mode <strong>of</strong> cultivation is practised

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

little bit like paradise when <strong>the</strong>y appear in front <strong>of</strong> someone who reaches <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> a hill. I<br />

have never seen such natural, green and beautiful scenery before.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts are divided into three districts 6 , Bandarban, Rangamati and<br />

Kagrachari. Rangamati as <strong>the</strong> biggest district has an area <strong>of</strong> 6,089 square kilometres and is<br />

divided into nine thanas. Bandarban, <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn district covers about 4,502 square kilometres,<br />

subdivided into seven thanas. <strong>The</strong> smallest district is <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Kagrachari, covering<br />

2,590 square kilometres and divided into eight thanas (Ullah 1995, 99).<br />

<strong>The</strong> inhabitants are categorised into 13 different groups 7 . <strong>The</strong> major ones are <strong>the</strong> Chakma,<br />

Marma and Tripura, <strong>the</strong> minor ones are: Tanchangya, Riyang, Khumi, Murong, Lushai, Kuki,<br />

Bawm, Kheyang, Pankhua and Chak 8 . Every group has its own language, dress and social<br />

customs, so that one can say that every one has its own culture 9 . <strong>The</strong>se groups can be roughly<br />

divided into two categories: <strong>the</strong> valley groups, comprising Marma, Chakma and Tripura, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs who live on <strong>the</strong> ridges <strong>of</strong> hills. 10 <strong>The</strong>re has always been a small minority <strong>of</strong> Bengalis<br />

in <strong>the</strong> area, as well as some non-tribal Hindu communities and non-tribal Buddhists.<br />

Until 1951 <strong>the</strong> population remained small in numbers; <strong>the</strong> population census <strong>of</strong> that year estimated<br />

a density <strong>of</strong> 57 inhabitants per square kilometre, which has grown to 190 per square<br />

kilometre until 1991. 11<br />

In <strong>the</strong> following I will give a short description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main groups which I have selected on<br />

<strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> my experiences in <strong>the</strong> field.<br />

Chakma:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Chakma are <strong>the</strong> biggest group among <strong>the</strong> Hill Peoples. <strong>The</strong>y belong to <strong>the</strong> Mongoloid<br />

group and <strong>the</strong>ir language originates in <strong>the</strong> Indo-Aryan group. <strong>The</strong>ir descent is unclear, as <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have, like <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r groups, no written history and different <strong>the</strong>ories about <strong>the</strong>ir origin. Some<br />

6 See map in appendix<br />

7 Again <strong>the</strong> number varies. Some authors mention less or more than 13, for example Bernot (1960) mentions 10.<br />

My decision to assume <strong>the</strong>re are 13 groups is backed by Mohsin (1997), Shelley (1992) and my Chakma informants<br />

in <strong>the</strong> field<br />

8 In <strong>the</strong> literature <strong>the</strong> spelling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> names varies. Shelley (1992, 45) examines <strong>the</strong>se most broadly<br />

9 For <strong>the</strong> conception <strong>of</strong> culture which is used in this paper see Chapter 6<br />

10 T.H. Lewin who served as an British administrator in <strong>the</strong> 19 th century in <strong>the</strong> hills and who has published two<br />

basic ethnological books on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts named <strong>the</strong>m according to this distinction Khyoungtha and<br />

Toungtha which is Burmese-Arakanese and means “children <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> river” and “children <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hills”<br />

11 To recognise <strong>the</strong> immense growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHT is important for several reasons. Until <strong>the</strong> Pakistan regime <strong>the</strong><br />

area was an “excluded area” which means that no one could settle in <strong>the</strong> CHT if he had not got permission from<br />

<strong>the</strong> tribal-chiefs and <strong>the</strong> deputy commissioner. Later under Bangladesh regime <strong>the</strong> CHT were used to rehabilitate<br />

landless Bengalis from <strong>the</strong> plains. <strong>The</strong> influx <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se settlers enlarged <strong>the</strong> density <strong>of</strong> population immensely,<br />

especially <strong>the</strong> non-tribal portion.

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> Chakma to be <strong>of</strong> Muslim origin, o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ories, particularly those which are<br />

propagated by <strong>the</strong> Chakma <strong>the</strong>mselves, tell that <strong>the</strong>y migrated from a place called Champaknagar<br />

12 to <strong>the</strong> Hill Tracts (Mohsin, 1997, 12ff). This unclearness is sometimes utilised for<br />

political discussions, as <strong>the</strong>y are regarded as being a “rootless tribe” by Abedin 13 (1997, 58).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Chakma are Buddhists, whose society shows patriarchal patterns, and <strong>the</strong>y are not just<br />

numerically <strong>the</strong> dominant group in <strong>the</strong> CHT. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> political leaders who influence <strong>the</strong><br />

policies and processes <strong>of</strong> decision are members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chakma, as well as those taking part in<br />

insurgency actions. 14 <strong>The</strong>y are concentrated in Rangamati and Kagrachari district. In Rangamati<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> vast majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> indigenous populations and <strong>the</strong> Rajbari 15 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chakma<br />

chief is located <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

Marma:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Marma, who also belong to <strong>the</strong> Mongoloid group are Buddhists as well. <strong>The</strong> Marma<br />

community is divided into two; one mainly lives in and around Bandarban, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r in<br />

Kagrachari. 16 Both <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se groups came from Arakan in Burma. <strong>The</strong> word Marma itself derives<br />

from <strong>the</strong> name “Myanmar” for <strong>the</strong> Burmese nation (Prue, 1994, 1). <strong>The</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Marma<br />

came to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong area in <strong>the</strong> 17 th century, went back to Arakan in 1756 under Moghal<br />

pressure until <strong>the</strong>y finally reached Bandarban in <strong>the</strong> 19 th century. <strong>The</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Marma were<br />

refugees driven out <strong>of</strong> Arakan some time later (Mohsin 1997, 15). As I was told at <strong>the</strong> Tribal<br />

Cultural Institute in Bandarban, <strong>the</strong> Marma language and script (which is almost forgotten) is<br />

very similar to Arakanese. Unusual for <strong>the</strong> CHT groups is <strong>the</strong> latent bias towards matriarchal<br />

societal structures among <strong>the</strong> Marma, which is revealed by <strong>the</strong> literature (Shelley 1992, 53).<br />

My empirical data show that <strong>the</strong> Marma gender order can considered to be extraordinary in<br />

comparison to <strong>the</strong> Bengali society 17 . Norms in respect to <strong>the</strong> occupation <strong>of</strong> public spaces for<br />

12 <strong>The</strong>re is no hint to find where <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Champaknagar was. Some <strong>the</strong>ories maintain that it was located near<br />

Malacca, in Tripura, in Bihar or somewhere in Thailand<br />

13 His opinion about <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r groups is not better. In <strong>the</strong> Chapter “CHT: Home <strong>of</strong> Alien Tribes” he writes: „All<br />

<strong>the</strong> tribes living in <strong>the</strong> CHT are outsiders and none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m are sons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> soil” (Abedin 1997, 53)<br />

14 <strong>The</strong> Chakma-dominance among <strong>the</strong> hill people will be explained and analysed more broadly in <strong>the</strong> following<br />

chapters. This fact is essential for <strong>the</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamics <strong>of</strong> ethnicity and identity-construction.<br />

15 <strong>The</strong> chiefs’ residence<br />

16 Mohsin tells that <strong>the</strong>y had two chiefs, <strong>the</strong> Bohmang Raja in Bandarban, <strong>the</strong> Mong Raja in Ramgarh. <strong>The</strong><br />

community was divided by <strong>the</strong> Karnafuli river, those living south were headed by <strong>the</strong> Bohmang chief, those<br />

living in <strong>the</strong> north were ruled by <strong>the</strong> Mong chief. Of interest here are <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Marma, since I have been in<br />

Bandarban and have very little knowledge about <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn group. As I was told <strong>the</strong> difference is not <strong>of</strong> great<br />

importance<br />

17 During my field work I observed that <strong>the</strong> gender order among <strong>the</strong> Hill People varies to some extent from that<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bengali society. <strong>The</strong>se differences can be traced back to religion for example and will be examined in<br />

Chapter 6 more broadly

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

example are very different to those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bengali community and even to those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Hill People. Smoking in public spaces is not a taboo for <strong>the</strong>m. Receiving guests in a Marma<br />

house is <strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> woman. I have heard several times in <strong>the</strong> field: “our women are very<br />

active”.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Hindu 18 Tripura are <strong>the</strong> third largest group. Since <strong>the</strong>y have no chief <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own, <strong>the</strong><br />

Tripura live within <strong>the</strong> jurisdictions <strong>of</strong> Marma or Chakma rajas. <strong>The</strong>ir origin is considered to<br />

be in <strong>the</strong> Indian state <strong>of</strong> Tripura, which borders on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHT. <strong>The</strong> Tripura<br />

are mainly concentrated in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Kagrachari district. <strong>The</strong> Murong are living predominantly<br />

in Bandarban district. <strong>The</strong>y are Animists and have no religious book. <strong>The</strong>ir cultural<br />

background and <strong>the</strong>ir social customs are sometimes regarded as extraordinary 19 . <strong>The</strong> Murong<br />

believe that a bull was sent by <strong>the</strong>ir god Turai to carry <strong>the</strong> religious book but had eaten it up<br />

on <strong>the</strong> way (Mohsin 1997, 18). Informants told that <strong>the</strong>y have special rituals like playing <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

pipe in return for baksish. <strong>The</strong> Chak and Tanchangya are considered as sub-groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Chakma. In general <strong>the</strong>re has been very little knowledge about <strong>the</strong> smaller groups, since <strong>the</strong>y<br />

lived isolated from <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs (Mohsin, 1997, 20).<br />

1.2. <strong>The</strong>oretical Presumptions<br />

<strong>The</strong>ories on identity construction are broad. Among <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ories on <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> ethnic<br />

identity, likewise national identity, two guiding positions can be distinguished. <strong>The</strong> first comprises<br />

<strong>the</strong> idea that ethnicity is a stable, contingent characteristic, tied to social circumstances,<br />

in which individuals are socialised and to which <strong>the</strong>y belong. Contrasting this primordialist<br />

perspective, an instrumentalist perspective, grounded in <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> Frederic Barth (1969),<br />

has been developed, which largely dominates <strong>the</strong> discourse on ethnicity. <strong>The</strong> instrumentalist<br />

notion can be supplemented by a third strain, <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> rational choice (Kößler 1995, 3). <strong>The</strong><br />

combination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se two ideas comprises <strong>the</strong> assumption that ethnicity is seen as a construction,<br />

an invention 20 , on <strong>the</strong> one hand, and that ethnicity can be <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> a rational choice, a<br />

strategy, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand. That <strong>the</strong>orem, guided by an idea <strong>of</strong> constructivism, comprises<br />

according to Barth (1998, 6) three main features. First, ethnicity is <strong>the</strong> social organisation <strong>of</strong><br />

cultural difference. Second, ethnicity is a matter <strong>of</strong> self-ascription and ascription by o<strong>the</strong>rs in<br />

18 According to my field experience <strong>the</strong>re are some Tripura who have converted to Christianity. That fact does<br />

not appear in <strong>the</strong> literature<br />

19 Literature: Schendel 1992a, Shelley 1992, 54. In <strong>the</strong> Bengali society a visitor will consider various kinds <strong>of</strong><br />

stereotypes towards <strong>the</strong> CHT peoples in general.

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

interaction and <strong>the</strong>refore constructed by <strong>the</strong> actors <strong>the</strong>mselves. Third, <strong>the</strong> boundaryconnectedness<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural features, implying that <strong>the</strong> actors <strong>the</strong>mselves develop diacriteria<br />

along which members and non-members are categorised, included or excluded. <strong>The</strong> key element<br />

<strong>of</strong> ethnicity is <strong>the</strong> stability <strong>of</strong> boundaries between groups (von Bruinessen 1997, 196).<br />

<strong>The</strong> cultural features <strong>the</strong>mselves are flexible. According to rational decisions <strong>the</strong>se “markers”<br />

can be constructed: clothing, language, food habits, religion or modes <strong>of</strong> cultivation gain importance,<br />

whenever rational calculation stresses <strong>the</strong>ir concern. A common history can be<br />

invented, whenever it is considered to be necessary. Cultural features can become activated,<br />

when pressure from outside for example requires (Kößler 1995, 4). Pressure can have its origins<br />

in political as well as economic processes (Schlee 1996, 20), <strong>the</strong> resulting inclusion<br />

based on cultural features <strong>the</strong>n affects those processes vice versa. At <strong>the</strong> same time flexibility<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultural features can have <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> various identities as a consequence: Depending<br />

on <strong>the</strong> concern which is considered to be important, different identities are stressed:<br />

in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People three or more different levels can’t be distinguished: <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi<br />

identity, <strong>the</strong> Hill People’s identity, <strong>the</strong> group’s identity and <strong>the</strong> clan’s identity. Schlee<br />

(1996) defines <strong>the</strong>se as pluritactic constructions.<br />

Starting from this very general <strong>the</strong>oretical base, after presenting <strong>the</strong> methodology, I will first<br />

examine <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> nationalism and counter-nationalism in Bangladesh and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong<br />

Hill Tracts. Mechanisms <strong>of</strong> inclusion and exclusion related to political processes are<br />

explored here. Secondly economic processes are analysed with regard to <strong>the</strong>ir importance for<br />

processes <strong>of</strong> group-formation. Education in Chapter 5 is treated as a kind <strong>of</strong> excurse. After<br />

analysing three exemplary “markers”, cultural features will be <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> Chapter 6, embedded<br />

into a <strong>the</strong>oretic conclusion. As a question <strong>of</strong> current interest <strong>the</strong> Peace Accord is<br />

examined and an outlook about <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> ethnic relations in <strong>the</strong> CHT will be given<br />

here. <strong>The</strong> main aspects will be summarised in a final conclusion.<br />

2. Methodology<br />

“You should always keep in mind three things. First, you are in a tribal area. Second, tribals<br />

are shy. Third, <strong>the</strong>y are sensitive”<br />

To investigate identity construction I conducted field work in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts. In<br />

<strong>the</strong> beginning organisational problems hindered my attempt to start, but after two weeks “acclimatisation”<br />

in Bangladesh I found a NGO with projects in <strong>the</strong> CHT, namely <strong>the</strong> Integrated<br />

20 Revealed by Hobsbawm’s notion on <strong>the</strong> invention <strong>of</strong> Tradition (Der Spiegel 1999 Nr. 52, pp. 144-148)

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

Development Foundation (IDF). <strong>The</strong> field trip consisted <strong>of</strong> three phases: First I spent eight<br />

days in Rangamati and immediately after one week in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn district <strong>of</strong> Bandarban 21 .<br />

After a break <strong>of</strong> approximately two weeks I returned to Rangamati for ano<strong>the</strong>r nine days.<br />

Helpful like all Bangladeshis, in my experience , IDF organised my first journey to Rangamati<br />

and a suitable accommodation. Besides my hosts interest in my work <strong>the</strong>y had enough<br />

time to introduce me to different areas <strong>of</strong> social life in <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> Rangamati in <strong>the</strong> Hill<br />

Tracts. <strong>The</strong> host provided me with access to members and leaders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> local elite as well as<br />

to people <strong>of</strong> lower socio-economic status and villagers around Rangamati. An immense advantage<br />

for <strong>the</strong> field entry was my hosts’ knowledge <strong>of</strong> English, which made it possible to do<br />

research without finding an interpreter first. <strong>The</strong> difficulties <strong>of</strong> understanding, which are discussed<br />

by Bernard (1995, 145) were not as problematic because even among <strong>the</strong> villagers a<br />

lot <strong>of</strong> people know English and if necessary my informants translated. Additionally IDF gave<br />

me <strong>the</strong> chance to visit development projects in <strong>the</strong> area and provided an insight into <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

work in general. Besides that I was able to use <strong>the</strong> contacts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> host-family to visit o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

NGOs as well as governmental development organisations. Through <strong>the</strong>se contacts my sample<br />

was largely influenced: finding people for interviews presupposes that <strong>the</strong> researcher<br />

knows somebody who knows someone and so on. <strong>The</strong> fact that I had, by accident, wonderful<br />

informants differing in age and position, provided me with contact to a broad variety <strong>of</strong> interviewees.<br />

To realise <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> “<strong>the</strong>oretical sampling” (Strauss 1994) to a certain extent was<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore easy, as I was still able to express preferences about whom I would like to meet besides<br />

<strong>the</strong> contacts I got through <strong>the</strong> family contact in general 22 . During <strong>the</strong> first time I spent in<br />

Rangamati I talked to several members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> traditional elite, teachers, people working in<br />

government jobs and international organisations, employees <strong>of</strong> several NGOs and <strong>the</strong>ir members,<br />

former insurgents, unemployed people, villagers and several members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> political<br />

elite. During <strong>the</strong> second term at Rangamati I visited additionally <strong>the</strong> Tribal Cultural Institute<br />

and some o<strong>the</strong>r villages; fur<strong>the</strong>rmore I intensified some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> former contacts. <strong>The</strong> sample<br />

consisted exclusively <strong>of</strong> Chakma apart from contacts I had to a few Bengalis. This is indeed<br />

not a representative sample for investigating an area in which 13 different indigenous groups<br />

are living, besides many Hindu and Muslim Bengalis and smaller non-indigenous and non-<br />

Bengali groups 23 . But <strong>the</strong> limitedness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time-frame as well as <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> indigenous<br />

21 My experiences in Bandarban will be described later. <strong>The</strong> two cases are kept apart as <strong>the</strong> experiences are quite<br />

different<br />

22 It was impossible <strong>of</strong> course to reach a certain saturation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sample<br />

23 <strong>The</strong> Barua mentioned in Chapter 6

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

population <strong>of</strong> Rangamati is predominantly Chakma 24 turned out to be a structural constraint.<br />

Contacts to Bengalis were even more difficult as in this conflict-ridden area ethnic<br />

segregation is well practised. Having once access to <strong>the</strong> Chakma circle, I recognised it as extremely<br />

difficult to establish any connection to Bengali inhabitants, except formal contacts to<br />

shopkeepers for instance.<br />

2.1. Applied Methods - Expectations and Reality<br />

According to Lentz (1992, 320f) qualitative methods are appropriate when <strong>the</strong> researcher does<br />

not have much knowledge about <strong>the</strong> field. <strong>The</strong> close relationship to my host-family was a<br />

good basis for concentrating on participant observation (Bernard 1995, 136ff). Especially during<br />

<strong>the</strong> first days I was very curious about everything that I observed, that was different from<br />

my own or <strong>the</strong> Bengali society. Every detail had to be considered as being important (Bernard<br />

1995, 147). Besides participant observation I made interviews which turned out to be quite<br />

different from what I expected. As my research topic is a very sensitive one, a lot <strong>of</strong> distrust<br />

and reluctance hampered collecting <strong>the</strong> data. Using a recorder while interviewing was impossible<br />

and formal interview-situations turned out to be counter-productive. Whenever a<br />

“classical interview-situation” 25 appeared, <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gained information was reduced<br />

to a non-satisfying level. I got <strong>the</strong> impression that people became suspicious whenever <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were reminded that I am not just a visitor but a researcher. Informal interviews, talks, conversations<br />

while having a drink and sitting toge<strong>the</strong>r on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand were very informative. In<br />

<strong>the</strong>se situations people sometimes chatted among <strong>the</strong>mselves, from time to time somebody<br />

summarised <strong>the</strong> conversation for me. Whenever I had any questions I could address <strong>the</strong>se<br />

openly. In some situations I became aware that people took me for a donor or some representative<br />

and started to complain about <strong>the</strong>ir disadvantaged situation as a minority, which is <strong>of</strong><br />

course quite important but limited my possibilities in investigating issues related to every-day<br />

life. When I got an audience from Shantu Larma for example my informant in advance and<br />

Shantu himself during <strong>the</strong> talk asked me directly to do something for <strong>the</strong> CHT and support <strong>the</strong><br />

24 Although eight different groups are scattered throughout Rangamati district (Ullah 1995, 99), most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m are<br />

living in remote villages which I could not reach during <strong>the</strong> short time I had. <strong>The</strong> Bengali population is approximately<br />

50%<br />

25 <strong>The</strong> situation <strong>of</strong> a researcher addressing serious questions to an interviewee

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Peace Accord <strong>of</strong>ficially. I was merely put into an advocacy-role<br />

(Lachenmann 1995, 6), although I always emphasised that I am not an influential person.<br />

<strong>The</strong> close relationship to my informants and interviewees turned out to be more problematic<br />

than expected. As Levi-Strauss (1978, 378) notes, a researcher has two possibilities: to represent<br />

<strong>the</strong> values <strong>of</strong> one’s own group or to submit oneself totally to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, which implies<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> objectivity. In my case it was merely a question <strong>of</strong> sympathy for ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Hill People<br />

or Bangladesh and <strong>the</strong> Bengalis. Sometimes I found myself in <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> judging too fast<br />

without considering my situation as a researcher, who is asked to have a merely neutral position<br />

(Lachenmann 1995, 6). Statements like “<strong>the</strong>se Bengalis are all <strong>the</strong> same” whenever <strong>the</strong>re<br />

was reason to complain influenced me so, that I had some problems to force myself to take a<br />

neutral position again. Being encapsulated in <strong>the</strong> field I recognised from time to time as being<br />

an enormous emotional burden. <strong>The</strong> destiny <strong>of</strong> some people I was confronted with in <strong>the</strong> context<br />

<strong>of</strong> 25 years’ armed conflict was sometimes hard to bear. <strong>The</strong> good understanding and<br />

warm kindness I experienced during my field work 26 , whilst limiting my objectivity enormously<br />

sometimes, gave me at <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>the</strong> possibility to get very attached to <strong>the</strong> field, a<br />

necessity for good participant observation.<br />

2.2. <strong>The</strong> Necessity <strong>of</strong> Somebody Who Takes Care<br />

After <strong>the</strong> first week in Rangamati I spent a fur<strong>the</strong>r one organised by IDF in Bandarban. <strong>The</strong><br />

research situation was quite different as it was only possible to find accommodation in a hotel.<br />

<strong>The</strong> field access was even more difficult because I did not get an informant with <strong>the</strong><br />

necessary ability to communicate in English. This was <strong>the</strong> first time I realised <strong>the</strong> language<br />

problem mentioned by Bernard (1995, 145f), which hampered <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> gaining information<br />

immensely and produced a lot <strong>of</strong> misunderstandings 27 . Making appointments for instance<br />

was difficult for myself as I had not enough knowledge to find <strong>the</strong> people, finding someone’s<br />

house was already complicated enough 28 .To overcome <strong>the</strong> distance to <strong>the</strong> field, I recognised<br />

<strong>the</strong> opportunity to try new methods like formal and expert interviews. Additionally I could<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>it from having different informants which opened new fields and situations. This mix <strong>of</strong><br />

26 Without <strong>the</strong> Bengali habit <strong>of</strong> staring at me wherever I appeared, which got on my nerves quite a lot sometimes<br />

when in Bengali dominated areas. A habit which influenced my sympathy immensely, when I recognised <strong>the</strong> shy<br />

behaviour <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People in observing me. Even in <strong>the</strong> villages people came, as if by accident, to have a look<br />

at me from a safe distance<br />

27 In Bandarban I got <strong>the</strong> impression that <strong>the</strong>re is a visible difference in <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> education in comparison to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Chakma (examined in Chapter 5). Communication was even harder as <strong>the</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> groups is broader and<br />

with this <strong>the</strong> languages<br />

28 As <strong>the</strong>re are no street-names and numbers

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

different methods and changed perspectives, which are known as triangulation in <strong>the</strong><br />

qualitative research methodology (Flick 1995, 250), was an important component <strong>of</strong> my research<br />

process. Besides difficulties concerning <strong>the</strong> field-entry <strong>the</strong> police <strong>of</strong> Bandarban became<br />

suspicious about my work. <strong>The</strong>y realised that I am not just a tourist I had to visit <strong>the</strong> police<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice regularly to report about my activities. Having only a few references to justify my stay<br />

in Bandarban, no direct contact to anyone who could defend me, <strong>the</strong> situation turned to be<br />

problematic and caused an earlier departure than had been planned. Again, that problem <strong>of</strong><br />

being thought a spy must be considered as a danger <strong>of</strong> certain field work in general (Bernard<br />

1995, 144). It would have been helpful to have an <strong>of</strong>ficial research permit.<br />

Altoge<strong>the</strong>r I interviewed some members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> traditional elite <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bandarban Marma circle,<br />

employees <strong>of</strong> various developmental organisations from different departments 29 , activists<br />

in <strong>the</strong> JSS <strong>of</strong>fice in Bandarban and <strong>the</strong> political elite, some intellectuals <strong>of</strong> various occupations,<br />

members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> credit programmes <strong>of</strong> IDF, employees and students <strong>of</strong> a residential<br />

school and “normal” families. <strong>The</strong> interviewees were mainly Marma, a few Tripura and<br />

Murong as well as Bengalis. Although my sample and <strong>the</strong> information I got satisfied me afterwards,<br />

<strong>the</strong> feeling <strong>of</strong> not getting “real access” to <strong>the</strong> field was <strong>the</strong>re during my stay in<br />

Bandarban. Without being in close touch with someone, fieldwork can turn out to be problematic.<br />

3. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts and <strong>the</strong> Nation-State<br />

“To understand <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts it is essential to have some knowledge<br />

about <strong>the</strong> history”, said an informant before he started to explain <strong>the</strong> historical<br />

development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conflict between <strong>the</strong> Hill People and Bangladesh. For my research purposes,<br />

<strong>the</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ethnic segregation and <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong><br />

identity, investigating history and development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation-state is particularly essential.<br />

In this chapter I will roughly describe some major changes in <strong>the</strong> period <strong>of</strong> British colonialisation<br />

and <strong>the</strong> massive ones during <strong>the</strong> Pakistan period, in which <strong>the</strong> patterns <strong>of</strong> life changed<br />

totally especially with <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation state and <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kaptai<br />

dam 30 . After Bangladesh became independent in 1972, <strong>the</strong> Bangladesh nationalist movement<br />

created rising insurgency, which lasted until December 1997. A peace treaty between <strong>the</strong><br />

29 For example an agriculturist, a health worker and co-ordinators <strong>of</strong> credit programmes<br />

30 As an very important issue <strong>the</strong> Kaptai Dam will not just be <strong>of</strong> interest here but in Chapter 4.1 as well.

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

Bangladesh government and <strong>the</strong> Paratya Chattrogram Jana Sanghati Samiti (PCJSS), <strong>the</strong> political<br />

front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts people, was signed.<br />

3.1. British Colonialism and <strong>the</strong> Pakistan Period<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no literature about <strong>the</strong> CHT before <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> British colonial power to be<br />

found. As in many societies with limited access to writing and reading, knowledge about <strong>the</strong><br />

past is based on oral history. <strong>The</strong> first person who wrote about <strong>the</strong> CHT was Francis Buchanan,<br />

who travelled Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Bengal in 1798 in search <strong>of</strong> places for <strong>the</strong> cultivation <strong>of</strong><br />

spices (van Schendel 1992). Later <strong>the</strong> British administrators Hutchinson (1906) and Lewin<br />

(1869) published <strong>the</strong> first quasi-ethnologic studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area 31 . <strong>The</strong>y pointed out that <strong>the</strong> administration,<br />

<strong>the</strong> social structure and political system were <strong>of</strong> a typical tribal character in a<br />

clan-order.<br />

“In <strong>the</strong> hills <strong>the</strong> different peoples were basically self-governing small entities without highly<br />

formalised political systems, whereas <strong>the</strong> people in <strong>the</strong> plain were always subject to an external<br />

power”. (Bangladesh Group Nederland: Roy 1995, 50)<br />

British Colonialism:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts were ceded to <strong>the</strong> British East India Company by Nawab Mir Qasim<br />

Ali Khan, who was <strong>the</strong> semi-independent governor under <strong>the</strong> Moghals in 1760. Until<br />

1900 <strong>the</strong> main objectives by which <strong>the</strong> British policy was guided were <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

own political, economic and military interests as well as keeping <strong>the</strong> Hill People segregated<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Bengalis (Mohsin 1997, 26). In 1860 <strong>the</strong> area was separated from <strong>the</strong> district <strong>of</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong<br />

and became <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts as it remained until today. But <strong>the</strong> British<br />

colonialists did not establish any administrative structure worth mentioning, as <strong>the</strong> contacts<br />

were limited to <strong>the</strong> payment <strong>of</strong> taxes (Shelley 1992, 28). <strong>The</strong>ir policies included <strong>the</strong> legal and<br />

judicial system was being simplified so far that <strong>the</strong> Hill People could retain <strong>the</strong>ir traditional<br />

norms and institutions (Ahsan 1989, 962).<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts Regulation 1900, <strong>the</strong> district <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHT was divided<br />

into three circles under supervision <strong>of</strong> a deputy commissioner. Following <strong>the</strong> traditional struc-<br />

31 In <strong>the</strong> Tribal Cultural Institute <strong>of</strong> Rangamati and Bandarban I was able to have a look into <strong>the</strong>se publications.<br />

Unfortunately I could not go into it more deeply because <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> copy-machines and time

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

tures <strong>the</strong>se were <strong>the</strong> Chakma, Mong and Bohmong 32 , each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m placed under <strong>the</strong><br />

jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> a tribal chief who collected revenues 33 and managed internal affairs. According<br />

to <strong>the</strong>se circles subdivisional <strong>of</strong>ficers were responsible to <strong>the</strong> deputy commissioner. <strong>The</strong> circles<br />

were subdivided into mouza and para (Ahsan 1090, 962). <strong>The</strong> mouza, ruled by a<br />

headman, is itself subdivided into paras where karbaris 34 represent <strong>the</strong> chief in all social affairs.<br />

<strong>The</strong> following act, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts (Amendment) Regulation <strong>of</strong> 1920<br />

declared <strong>the</strong> CHT to be a so-called excluded area. Besides <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> British safeguarded<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir financial and administrative interests, <strong>the</strong> exclusive status provided special rights and<br />

privileges for <strong>the</strong> tribals living in <strong>the</strong> CHT, especially related to land and settlement. <strong>The</strong> Hill<br />

People had a self-governmenting system to a considerably large extent. (Shelley 1992, 28;<br />

D’Souza 1995, 161; Löffler 1968).<br />

With <strong>the</strong> partition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Indian subcontinent, <strong>the</strong> Hill People were caught in a difficult situation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> question to which <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new created states <strong>the</strong> CHT would belong affected all Hill<br />

People equally, but <strong>the</strong>ir interests were not represented properly. <strong>The</strong> elite <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> different<br />

groups was not united itself: <strong>the</strong> Chakma elite was mainly in favour <strong>of</strong> union with India, while<br />

<strong>the</strong> Marma supported Burma (Mey 1988, 40). This explains <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> Chakma hoisted<br />

<strong>the</strong> Indian flag at Rangamati, <strong>the</strong> Marma <strong>the</strong> Burmese flag in Bandarban before <strong>the</strong> CHT became<br />

a part <strong>of</strong> Pakistan on <strong>the</strong> 16 th August 1946, as a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong division, a<br />

decision guided by mainly administrative and strategic reasons: <strong>the</strong> CHT were exchanged for<br />

Ferozepur in India, where trouble among <strong>the</strong> local Sikhs was expected if Ferozepur were to<br />

allotted to Pakistan (Mey 1988, 40).<br />

Pakistan Period:<br />

<strong>The</strong> relationship between <strong>the</strong> Pakistan Government and <strong>the</strong> CHT remained difficult during <strong>the</strong><br />

whole Pakistan period. Contemporarily with <strong>the</strong> first Pakistani constitution in 1956 <strong>the</strong> Regulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1900 and <strong>the</strong> status <strong>of</strong> an excluded area was retained and <strong>the</strong> Hill People were given<br />

<strong>the</strong> right to vote, which had stabilising consequences on <strong>the</strong> CHT situation. However <strong>the</strong> regime<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ayub Khan changed <strong>the</strong> administrative status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHT in 1962 from an “excluded<br />

32 <strong>The</strong> Mong and Bohmong are two different groups which both belong to <strong>the</strong> Marma group. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m is<br />

concentrated in <strong>the</strong> north mainly in Kagrachari, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r one that is <strong>the</strong> Mong have <strong>the</strong>ir residence in Bandarban<br />

as already stated in Chapter 1.2.<br />

33 Among <strong>the</strong>se taxes <strong>the</strong> jhum tax was <strong>the</strong> most important but also most troublesome. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People<br />

were attached to jhumming and <strong>the</strong>refore putting taxes on jhum was one pr<strong>of</strong>itable way <strong>of</strong> making money. Ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

reason for <strong>the</strong> tax was that jhum, as a traditional mode <strong>of</strong> cultivation, was regarded to be backward. <strong>The</strong> tax<br />

was <strong>the</strong>refore additionally one way <strong>of</strong> forcing <strong>the</strong> Hill People to take up modernised methods <strong>of</strong> cultivation<br />

34 Karbari is <strong>the</strong> headman <strong>of</strong> a village (para). A unit <strong>of</strong> villages is called mouza

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

area” to a “tribal area” 35 . Although <strong>the</strong> special status was abolished by a constitutional<br />

amendment in 1962, <strong>the</strong> Regulation <strong>of</strong> 1900 was kept operative and <strong>the</strong> Hill People still enjoyed<br />

some privileges. At this time <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> nation was used to consolidate Pakistani<br />

dominance over East Bengal, including <strong>the</strong> CHT (Mohsin 1997, 45ff). Alongside administrative<br />

and legal changes, Pakistan undertook some measures for economic development and <strong>the</strong><br />

utilisation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two major natural resources <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area, forestry and hydroelectricity. <strong>The</strong><br />

consequence was that a paper mill was established in 1950 and <strong>the</strong> Karnaphuli Multipurpose<br />

Project, beginning in 1957, resulted in <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> a dam which crossed <strong>the</strong> Karnaphuli<br />

river. <strong>The</strong> project was finished in 1963, established by <strong>the</strong> Pakistani government and<br />

financed by USAID (Shelley, 1992, 31). Like many o<strong>the</strong>r comparable development projects,<br />

none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> projects planners took into account how immense <strong>the</strong> impact on <strong>the</strong> inhabitants’<br />

project area would be 36 . <strong>The</strong> tribal interests have not been recognised at all. <strong>The</strong> dam built<br />

over <strong>the</strong> Karnaphuli next to Kaptai is about 666 metres long and 43 metres high. <strong>The</strong> product<br />

is an artificial lake which covers an area <strong>of</strong> about 655 sq. km 37 and has swallowed about 125<br />

moujas, including <strong>the</strong> major portion <strong>of</strong> Rangamati town (Ullah, 1995, 1). About 100,000 people<br />

were affected by <strong>the</strong> flooding. Although <strong>the</strong> compensation for homes and o<strong>the</strong>r belongings<br />

as well as <strong>the</strong> replacement <strong>of</strong> farmland that got lost was promised by <strong>the</strong> government, reports<br />

show that this has never happened. <strong>The</strong> result was that about 40,000 Chakmas crossed <strong>the</strong><br />

border to India as refugees (Ullah, 1995, 21). As 40% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> best cultivable land was flooded,<br />

<strong>the</strong> land given to <strong>the</strong> families by rehabilitation programmes was not sufficient for proper cultivation.<br />

About 1,500 families were completely left out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> scheme. Altoge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

government only compensated one third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flooded land (Mohsin, 1997, 114).<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> Karnaphuli power project was regarded as revolutionising Bangladesh’s industrialisation,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hill People could not really benefit from it. 38 During my stay in <strong>the</strong> CHT, I<br />

got <strong>the</strong> impression that <strong>the</strong> Karnaphuli Hydroelectric Project is <strong>the</strong> causal factor for most <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> problems in <strong>the</strong> area. Not only did an immense change <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> traditional patterns <strong>of</strong> life<br />

derive from it, including land problems 39 but also difficulties with <strong>the</strong> relationship to <strong>the</strong> ruling<br />

state in general 40 . Already at that time some ingenious students started to develop a<br />

35 <strong>The</strong> consequence was that <strong>the</strong> area remained distinctive but not excluded any longer<br />

36 A controversially discussed example which is presently discussed is <strong>the</strong> Narmada dam in India, by which<br />

approximately 4 Million people are affected (Chatterjee 1999)<br />

37 Regarding <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lake <strong>the</strong> data differ. Shelley (1992, 31) for example states that <strong>the</strong> submerged area is<br />

about 1036 kilometres. Unlike as in o<strong>the</strong>r cases (see Chapter 4.1), no political intention for <strong>the</strong> differing estimations<br />

can be seen. <strong>The</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> literature is uniform regarding <strong>the</strong> estimation <strong>of</strong> 40% <strong>of</strong> best cultivable land<br />

which was swallowed leads me to <strong>the</strong> assumption that <strong>the</strong> differences here are not <strong>of</strong> great importance.<br />

38 <strong>The</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> economic consequences <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kaptai Hydroelectric Project will be discussed in Chapter 4.<br />

39 In Chapter 4.1 <strong>the</strong> land issue will be analysed broadly<br />

40 See Chapter 3.2

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

political campaign against <strong>the</strong> government and represented “a new wave <strong>of</strong> Chakma and<br />

Marma political identity and consciousness” (Ahmed 1993, 39). <strong>The</strong> first conversation I had<br />

with a Chakma when I came to Rangamati ended after five minutes with <strong>the</strong> following statement:<br />

“This dam has caused all our problems we have here in <strong>the</strong> CHT”. Later he explained to<br />

me: “<strong>The</strong>y could give <strong>the</strong> tribals free access to electricity or fishery after this dammed lake<br />

has taken all our land, but it had just one intention: to destroy tribals’ life”.<br />

3.2. Bangladesh Becomes Independent<br />

In 1971 Bangladesh became independent after nine months <strong>of</strong> war. <strong>The</strong> Liberation War arose<br />

from an effort to free Bengal from <strong>the</strong> hegemonic system <strong>of</strong> Pakistan, which defines itself by<br />

religion. <strong>The</strong> ethnocentric political programme was guided by <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “pureness” 41 <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Islam which included <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> Urdu being <strong>the</strong> Islamic language 42 . <strong>The</strong> Bengalis were<br />

considered to be a lower Hindu caste although <strong>the</strong>y had actively supported <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> a Muslim<br />

Pakistani state 43 . <strong>The</strong> Pakistani hegemony <strong>the</strong>n led <strong>the</strong> Bengalis to assert <strong>the</strong>ir separate<br />

identity, which was now based on distinction through language and culture, instead <strong>of</strong> religion.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> exclusion from Pakistani Islamic nationalism a new form <strong>of</strong> nationalism<br />

guided by culture and language arose which became <strong>the</strong> guiding paradigm for <strong>the</strong> independent<br />

Bangladesh.<br />

3.2.1. Politics <strong>of</strong> Nationalism<br />

<strong>The</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi state is determined by two distinct forms <strong>of</strong> nationalism,<br />

namely <strong>the</strong> Bengali and <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi variant. <strong>The</strong> first one was developed and practised<br />

under Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who guided <strong>the</strong> independent movement and became <strong>the</strong> first<br />

political leader <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh. It comprises two dimensions, <strong>the</strong> cultural and <strong>the</strong> territorial<br />

one. <strong>The</strong> cultural dimension is particularly determined by <strong>the</strong> language movement 44 and secularism,<br />

both developed in <strong>the</strong> attempt to demarcate itself from West Pakistan, where Urdu as<br />

state-language and Islam as state-religion were considered as determining features <strong>of</strong> national-<br />

41 “pak” means pure, “stan” means land (Mohsin 1997, 38)<br />

42 Urdu is written in a Arabic Persian script, while Bengali was sanskritised by <strong>the</strong> Hindu elites during colonialisation<br />

(Mohsin 1996, 35)<br />

43 After <strong>the</strong> Muslim population <strong>of</strong> Bengal had been dominated by a Hindu aristocracy created by <strong>the</strong> British<br />

colonial policy Hindu as well as Muslim identity which arose after <strong>the</strong> pre-colonial syncretism (Mohsin 1996,<br />

74)<br />

44 Bangladesh literally translated means “<strong>the</strong> land <strong>of</strong> Bangla speaking people” (Mohsin 1997, 54)

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

ism. <strong>The</strong> Bengali nationalism was indeed specific about its territorial boundaries 45 <strong>of</strong> East-<br />

Bengal. This concept <strong>of</strong> Bengali nationalism thus was defined as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state principles in<br />

Article 9: “ <strong>The</strong> unity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bengali nation, which deriving its identity from its language and<br />

culture, attained sovereign and independent Bangladesh through a united and determined<br />

struggle in <strong>the</strong> war <strong>of</strong> independence, shall be <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> Bengali nationalism” (cited in:<br />

Mohsin, 1997, 60). Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore <strong>the</strong> ideology was based on a centralist idea <strong>of</strong> state under<br />

non-capitalist objectives, marked by <strong>the</strong> total integration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual within <strong>the</strong> community<br />

(Jahangir 1986, 33). Bangladesh with its uni-cultural, ethnocentristic nationalism<br />

developed <strong>the</strong> same kind <strong>of</strong> hegemony <strong>the</strong> population <strong>of</strong> East Bengal had to suffer during <strong>the</strong><br />

Pakistan period.<br />

When Sheikh Mujib was assassinated in 1975, <strong>the</strong> BNP with General Ziaur Rahman took over<br />

<strong>the</strong> political leadership. <strong>The</strong>ir concept <strong>of</strong> Bangladeshi nationalism, distinct from <strong>the</strong> Bengali<br />

variant, was determined mainly by religion 46 . This trend arose already increasingly after Mujib’s<br />

secularism. Territoriality became more determining in drawing a line between East and<br />

West Bengal in India and gave <strong>the</strong> state a new totality (Mohsin 1996, 47ff ). As a consequence<br />

this turn towards religion and territoriality had some substantial changes on different<br />

levels. Islamiat was introduced in <strong>the</strong> education system and fur<strong>the</strong>rmore administrative policies<br />

and mass media were induced by religious rituals. Additionally <strong>the</strong> Constitution was<br />

changed, <strong>the</strong> word “secularism” replaced by “absolute trust and faith in <strong>the</strong> Almighty Allah”<br />

(Jahangir 1986, 79f). Bangladesh’s policy became Islamised and as a consequence <strong>the</strong> citizens<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bangladesh were defined as Muslims as one unit against non-Muslims.<br />

Under General H.M. Ershad from 1982 onwards Bangladeshi nationalism moved towards<br />

Islamic nationalism. <strong>The</strong> model <strong>of</strong> nationhood became even more rigid and totalitarian in its<br />

Islamic orientation. He “raised <strong>the</strong> slogan <strong>of</strong> building a mosque-centred society” 47 and introduced<br />

Islam as <strong>the</strong> state religion through an amendment to <strong>the</strong> Constitution (Mohsin 1996,<br />

52).<br />

3.2.2. A Question <strong>of</strong> Identity – Bangladesh and <strong>the</strong> Hill People<br />

45 What is reflected by “Amar Sonar Bangla Ami Tomae Bhalobashi” (O my golden Bengal, I love <strong>the</strong>e) <strong>the</strong><br />

highly patriotic song written by Rabindranath Tagore as <strong>the</strong> national an<strong>the</strong>m.<br />

46 <strong>The</strong> BNP defined Bangladesh nationalism as follows: “Religious belief and love for religion are a great and<br />

imperishable characteristic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi nation ... <strong>the</strong> vast majority <strong>of</strong> out people are followers <strong>of</strong> Islam.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fact is well reflected and manifest in out stable and liberal national life” (Mohsin 1996, 49)<br />

47 <strong>The</strong> issue mosque-centredness and its meaning for <strong>the</strong> Hill People will be part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chapter 6.3.

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

<strong>The</strong> Hill People and <strong>the</strong> CHT played a controversial role in <strong>the</strong> War <strong>of</strong> Independence.<br />

<strong>The</strong> former Chakma Raja Tridiv Roy co-operated with Pakistan, but at <strong>the</strong> same time many<br />

Hill People joined <strong>the</strong> war in favour <strong>of</strong> independence. Never<strong>the</strong>less many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m had to face<br />

discrimination by <strong>the</strong> Bengalis 48<br />

(Mohsin 1996, 38). Immediately afterwards, some indigenous<br />

people were accused <strong>of</strong> being collaborators and killed. Violence against <strong>the</strong> Hill People<br />

continued for months. <strong>The</strong> excuse given by Sheikh Mujib, that such incidents are natural after<br />

a war 49 was not accepted at all by <strong>the</strong> Hill People. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m set up an administrative system<br />

for <strong>the</strong> villages and resisted <strong>the</strong> Bengalis 50 (Mohsin 1996, 39). <strong>The</strong> Hill People did not<br />

just demonstrate <strong>the</strong> failure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GOB to protect <strong>the</strong>ir rights but, more important, this was<br />

<strong>the</strong> first manifestation <strong>of</strong> group formation processes among <strong>the</strong> Hill People in order to “protect”<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves from Bengalis.<br />

Some Hill People’s representatives met Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to demand four basic arrangements<br />

for <strong>the</strong> CHT, under <strong>the</strong> leadership <strong>of</strong> Manabendra Narayan Larma 51 . <strong>The</strong>se<br />

included four points:<br />

(1) autonomy for <strong>the</strong> CHT including its own legislature<br />

(2) retention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1900 manual in <strong>the</strong> constitution <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh<br />

(3) continuation <strong>of</strong> tribal chiefs’ <strong>of</strong>fices<br />

(4) a constitutional provision restricting <strong>the</strong> amendment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1900 Regulation and imposing<br />

a ban on <strong>the</strong> influx <strong>of</strong> non-tribals (Ahsan, 1989, 967)<br />

Sheikh Mujib advised <strong>the</strong>m to get rid <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir tribal identities and merge with “Bengali” nationalism.<br />

As no special provision for <strong>the</strong> CHT was made in <strong>the</strong> 1972 constitution, M.N.<br />

Larma formed <strong>the</strong> Parbattaya Chattragam Jana Sanghati Samiti (PCJSS/JSS) as an oppositional<br />

political platform for <strong>the</strong> Hill People. Never<strong>the</strong>less in a pre-election meeting in<br />

Rangamati, Sheikh Mujib maintained that all tribal people are Bengalis and nothing else. According<br />

to <strong>the</strong> political programme <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> AL and Sheikh Mujib in particular distinct identities<br />

could not be accepted. In his view nationalism based on secularism should include <strong>the</strong> Hill<br />

People and any differences were denied. <strong>The</strong> demand to merge with Bengali nationalism was<br />

48 Mohsin emp hasises here that many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People could not join <strong>the</strong> forces because <strong>the</strong>ir ideological background<br />

did not fit in with those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Awami League which was responsible for recruiting <strong>the</strong> soldiers. Some<br />

Hill People came back from <strong>the</strong> training camps because <strong>of</strong> discrimination<br />

49 Stated by Charoo Bikash Chakma, who was <strong>the</strong> leader <strong>of</strong> a delegation which met Sheikh Mujib on 29 January<br />

1972 to appraise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation cited in Mohsin (1996, 39)<br />

50 <strong>The</strong> local youth recovered arms left behind by <strong>the</strong> Pakistan army in <strong>the</strong> jungles. <strong>The</strong>y were called Shanti Bahini,<br />

and can be seen as <strong>the</strong> early beginning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> armed wing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSS<br />

51 M.N. Larma was at that time member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi parliament and functioned, among o<strong>the</strong>rs, as a political<br />

leader <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People and formed <strong>the</strong> JSS. He was assassinated on 10 November 1983 by supporters <strong>of</strong> an<br />

opposing political group <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People. His younger bro<strong>the</strong>r, Shantu Larma took over his function and is <strong>the</strong><br />

present leader <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSS and Chairman <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHTRC

<strong>Eva</strong> <strong>Gerharz</strong><br />

not seen as a force but as an invitation, <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> Hill People should be grateful 52 . <strong>The</strong> Hill<br />

People already had to face discrimination by Bengalis and <strong>the</strong>ir relationship to <strong>the</strong> ruling state<br />

was due to <strong>the</strong> Kaptai dam, wholly determined by suspicion and doubt. Under <strong>the</strong> leadership<br />

<strong>of</strong> M.N. Larma <strong>the</strong> representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People’s community expressed <strong>the</strong>ir dissatisfaction<br />

with <strong>the</strong> state policies <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh. As a member <strong>of</strong> parliament M.N. Larma was able<br />

to articulate <strong>the</strong> Hill People’s interests directly, but instead he experienced paternalistic rejection<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se. <strong>The</strong> debate between M.N. Larma and his supporters on <strong>the</strong> one hand and Sheikh<br />

Mujib on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand has given rise to <strong>the</strong> conflict between <strong>the</strong> two groups. <strong>The</strong> nature <strong>of</strong><br />

Bengali nationalism with its ethnocentric and hegemonic outcome was categorically rejected<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Hill People. Bad experiences and <strong>the</strong> fear <strong>of</strong> becoming submerged under <strong>the</strong> majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bengalis has led to <strong>the</strong>ir being conscious <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir distinctiveness. <strong>The</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> any minority<br />

rights in <strong>the</strong> Constitution and <strong>the</strong> Bill declaring Bangladesh as a uni-cultural and unilingual<br />

nation-state has created a feeling <strong>of</strong> being oppressed by <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People.<br />

M.N. Larma asserted in <strong>the</strong> Parliament: “Our main worry is that our culture is threatened<br />

with extinction ... we want to live with our separate identity” (Mohsin 1996, 44). <strong>The</strong> emphasis<br />

on a separate identity in this context expresses <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> cultural habits in <strong>the</strong><br />

process <strong>of</strong> identity construction, but at <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>the</strong>ir importance is ultimately developed<br />

in a process <strong>of</strong> becoming conscious <strong>of</strong> it. <strong>The</strong> differentiation <strong>of</strong> groups itself is not <strong>the</strong> cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> conflict. Differences and cultural peculiarities become apparent when pressure and threat<br />

from outside or <strong>the</strong> dominant group within a nation-state necessitates inclusion for defence.<br />

(Kößler 1995, 4). With <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation-state <strong>the</strong> Hill People started to develop<br />

a unified identity as all groups were equally affected by <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bengali hegemony 53 .<br />

<strong>The</strong> government reacted to <strong>the</strong> appealing group-consciousness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People by dividing<br />

<strong>the</strong> CHT into <strong>the</strong> three districts: Rangamati, Bandarban and Kagrachari 54 . <strong>The</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> this<br />

measure was, as a Chakma expressed it in an interview, to cleave <strong>the</strong> Hill People and reduce<br />

<strong>the</strong> possibilities <strong>of</strong> collective resistance.<br />

General Zia’s Bangladeshi nationalism, which emphasised religion as <strong>the</strong> central feature <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi society, besides culture and language, alienated <strong>the</strong> Hill People fur<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Changes towards an Islamic orientation in mass media, education, administration and <strong>the</strong><br />

Constitution affected <strong>the</strong> Hill People even more directly. <strong>The</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> religion on every-day<br />

52 In his speech at Rangamati in 1973 Sheikh Mujib stated: “From this day onward <strong>the</strong> tribals are being promoted<br />

into Bengalis” (Mohsin 1996, 74)<br />

53 While <strong>the</strong> Kaptai Dam had mainly touched <strong>the</strong> Chakma and some groups, but some not at all<br />

54 In March 1989 <strong>the</strong> parliament passed several Bills which enabled <strong>the</strong> government to transform <strong>the</strong> administrative<br />

system with <strong>the</strong> resulting partition into <strong>the</strong> three districts (Mahmud Ali 1993, 162)

<strong>Construction</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Identities</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Chitta</strong>gong Hill Tracts<br />

life expressed in symbols and rituals confronted <strong>the</strong> Hill People massively with <strong>the</strong><br />

feeling <strong>of</strong> being different 55 .<br />

Recognising <strong>the</strong> rejection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill People’s demands by Zia and <strong>the</strong> BNP M.N. Larma<br />

started acting in <strong>the</strong> underground and formed <strong>the</strong> Shanti Bahini as <strong>the</strong> armed wing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JSS<br />

to enforce <strong>the</strong> demands <strong>of</strong> JSS in an armed struggle. Later he crossed over to India and started<br />

to launch massive guerrilla action against <strong>the</strong> Bangladesh authorities 56 (Ahmed 1993, 45).<br />

Training camps were established in India, fighters were recruited from <strong>the</strong> refugee camps and<br />

only a few years later <strong>the</strong> Shanti Bahini constituted a military and political threat for Bangladesh.<br />

<strong>The</strong> GOB reacted by militarising <strong>the</strong> area 57 . At <strong>the</strong> same time Zia tried to win over <strong>the</strong><br />

Hill People by drawing special attention to development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CHT 58 and developed a settlement<br />

programme for landless Bengalis who should be rehabilitated in <strong>the</strong> CHT 59 . His<br />

attempts were regarded as forced assimilation by using strategies <strong>of</strong> oppression. <strong>The</strong> settlement<br />

programme, although guided by pragmatic and humane intentions, established a<br />

demographic shift 60 in <strong>the</strong> area. <strong>The</strong> aim was to put <strong>the</strong> Hill People regionally into a minority<br />