CHAPTER 1: An introduction to time series and forecasting

CHAPTER 1: An introduction to time series and forecasting

CHAPTER 1: An introduction to time series and forecasting

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>CHAPTER</strong> 1: <strong>An</strong> <strong>introduction</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>forecasting</strong><br />

Basic Questions:<br />

1. What is a <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong>?<br />

2. What are the purposes of <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> analysis?<br />

3. what are the difference between classical (Independent Identically Distributed (IID)) statistical<br />

analysis (e.g. inference <strong>and</strong> modelling) <strong>and</strong> <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> analysis?<br />

1 Time Series<br />

A <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> is a sequence of observations over <strong>time</strong>.<br />

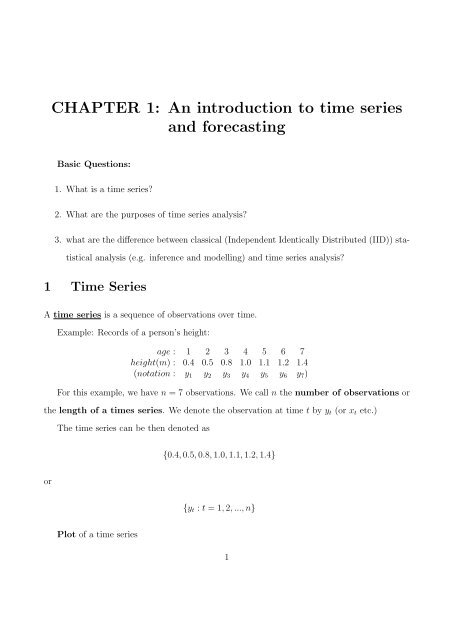

Example: Records of a person’s height:<br />

age : 1 2 3 4 5 6 7<br />

height(m) : 0.4 0.5 0.8 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.4<br />

(notation : y 1 y 2 y 3 y 4 y 5 y 6 y 7 )<br />

For this example, we have n = 7 observations. We call n the number of observations or<br />

the length of a <strong>time</strong>s <strong>series</strong>. We denote the observation at <strong>time</strong> t by y t (or x t etc.)<br />

The <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> can be then denoted as<br />

{0.4, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 1.4}<br />

or<br />

{y t : t = 1, 2, ..., n}<br />

Plot of a <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong><br />

1

1.5<br />

height<br />

1<br />

0.5<br />

0<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

age<br />

1.5<br />

height<br />

1<br />

0.5<br />

0<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

age<br />

Figure 1:<br />

Note that the above observations are taken over equally <strong>time</strong> intervals. We can also observe<br />

the variable with unequally <strong>time</strong> intervals<br />

age : 0.5 1 1.5 2 3 5 7<br />

height(m) : 0.35 0.4 0.45 0.5 0.8 1.1 1.4<br />

Theoretically, we can observe the data continuously <strong>and</strong> get a “continuous-<strong>time</strong>” <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong>.<br />

Remarks: We are mainly interested in discrete-<strong>time</strong> <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> with equally fixed <strong>time</strong><br />

intervals. e.g. observations made monthly, daily, weekly, etc.<br />

2

Example (Unemployment Rate (%) in Singapore)<br />

year rate year rate year rate<br />

1973 4.4 1984 2.7 1995 2.7<br />

1974 3.9 1985 4.1 1996 3.0<br />

1975 4.5 1986 6.5 1997 2.4<br />

1976 4.4 1987 4.7 1998 3.2<br />

1977 3.9 1988 3.3 1999 4.6<br />

1978 3.6 1989 2.2 2000 4.4<br />

1979 3.3 1990 1.7 2001 3.4<br />

1980 3.5 1991 1.9 2002 5.2<br />

1981 2.9 1992 2.7 2003 5.4<br />

1982 2.6 1993 2.7 2004 5.3<br />

1983 3.2 1994 2.6<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005<br />

Figure 2:<br />

More <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> [what can you observe in the <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong>?]<br />

7000<br />

Canadian Lynx captured (1828-1934)<br />

6000<br />

number of lynx<br />

5000<br />

4000<br />

3000<br />

2000<br />

1000<br />

0<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100 120<br />

<strong>time</strong> (year)<br />

Figure 3:<br />

3

35<br />

Temperature in Hong Kong (1994-1997)<br />

daily temperature in HK<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200<br />

Number of patients with respira<strong>to</strong>ry problems in Hong Kong (1994)<br />

300<br />

no. of patients<br />

250<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400<br />

<strong>time</strong> (daily)<br />

10000<br />

Measles cases in London (1944-1978)<br />

cases of measles<br />

8000<br />

6000<br />

4000<br />

2000<br />

0<br />

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000<br />

<strong>time</strong> (week)<br />

DOW s<strong>to</strong>ck index (1992-2005)<br />

15000<br />

DOW index<br />

10000<br />

5000<br />

0<br />

1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004<br />

<strong>time</strong><br />

return: z t<br />

= log(y t<br />

) −log(y t−1<br />

)<br />

0.1<br />

0.05<br />

0<br />

−0.05<br />

−0.1<br />

1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004<br />

<strong>time</strong><br />

4

2 Forecasting<br />

A major objective of <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> analysis is <strong>forecasting</strong> of future values of the <strong>series</strong><br />

e.g. what will be the unemployment rate next year?<br />

Is there a trend in global temperature?<br />

what is the seasonal effect?<br />

what is the relationship between GDP <strong>and</strong> interest rate?<br />

Forecasting methods:<br />

1. Qualitative <strong>forecasting</strong> methods: use the opinions of experts <strong>to</strong> predict future events<br />

subjectively.<br />

2. Quantitative <strong>forecasting</strong> methods: Based the his<strong>to</strong>rical data, use statistical methods <strong>to</strong><br />

predict future values of a variable.<br />

3 The difference between the <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> <strong>and</strong> IID statistics<br />

Time <strong>series</strong> data are dependent<br />

1. there is an order for the observation of <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong>.<br />

2. <strong>time</strong> <strong>series</strong> data are dependent. e.g. this month’s unemployment rate will be correlated<br />

with the last month’s.<br />

The problem with dependence:<br />

Consider the IID case<br />

X 1 , X 2 , · · · , X n r<strong>and</strong>om sample with mean µ <strong>and</strong> variance σ 2 . Then we estimate µ by<br />

ˆµ = (X 1 + X 2 + · · · + X n )/n<br />

5

The variance of ˆµ is<br />

we have V ar(ˆµ) → 0 as n → ∞.<br />

V ar(ˆµ) = 1 n 2 (V ar(X 1) + V ar(X 2 ) + ...V ar(X n )) = σ2<br />

n<br />

Imagine the situation where all the X i ’s are “perfectly” correlated, i.e.<br />

Cov(X i , X j ) = σ 2<br />

Corr(X i , X j ) = 1<br />

We still estimate µ by<br />

ˆµ = (X 1 + X 2 + · · · + X n )/n<br />

the variance is then<br />

V ar(ˆµ) = 1 n 2 V ar(X 1 + X 2 + · · · + X n )<br />

= 1 n∑<br />

n { V ar(X 2 i ) + 2 ∑ Cov(X i , X j )}<br />

i=1<br />

i