Volume 6 No 4 - Royal Air Force Centre for Air Power Studies

Volume 6 No 4 - Royal Air Force Centre for Air Power Studies

Volume 6 No 4 - Royal Air Force Centre for Air Power Studies

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

9<br />

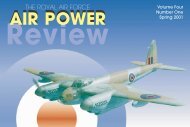

The best measure of the tempo of the Operation,<br />

the points at which objectives shifted, can be seen<br />

in the following graph which shows the cumulative<br />

usage of sea and air-launched Cruise missiles<br />

and of other PGMs 58 .<br />

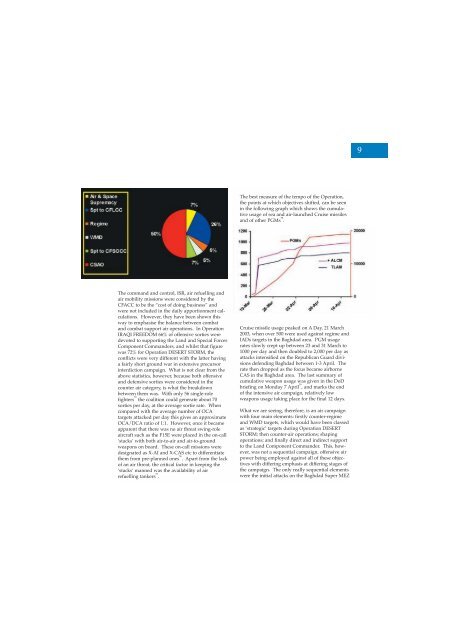

The command and control, ISR, air refuelling and<br />

air mobility missions were considered by the<br />

CFACC to be the “cost of doing business” and<br />

were not included in the daily apportionment calculations.<br />

However, they have been shown this<br />

way to emphasise the balance between combat<br />

and combat support air operations. In Operation<br />

IRAQI FREEDOM 66% of offensive sorties were<br />

devoted to supporting the Land and Special <strong>Force</strong>s<br />

Component Commanders, and whilst that figure<br />

was 72% <strong>for</strong> Operation DESERT STORM, the<br />

conflicts were very different with the latter having<br />

a fairly short ground war in extensive precursor<br />

interdiction campaign. What is not clear from the<br />

above statistics, however, because both offensive<br />

and defensive sorties were considered in the<br />

counter air category, is what the breakdown<br />

between them was. With only 56 single-role<br />

fighters 55 the coalition could generate about 70<br />

sorties per day, at the average sortie rate. When<br />

compared with the average number of OCA<br />

targets attacked per day this gives an approximate<br />

OCA/DCA ratio of 1:1. However, once it became<br />

apparent that there was no air threat swing-role<br />

aircraft such as the F15E were placed in the on-call<br />

‘stacks’ with both air-to-air and air-to-ground<br />

weapons on board. These on-call missions were<br />

designated as X-AI and X-CAS etc to differentiate<br />

them from pre-planned ones 56 . Apart from the lack<br />

of an air threat, the critical factor in keeping the<br />

‘stacks’ manned was the availability of air<br />

refuelling tankers 57 .<br />

Cruise missile usage peaked on A Day, 21 March<br />

2003, when over 500 were used against regime and<br />

IADs targets in the Baghdad area. PGM usage<br />

rates slowly crept up between 23 and 31 March to<br />

1000 per day and then doubled to 2,000 per day as<br />

attacks intensified on the Republican Guard divisions<br />

defending Baghdad between 1-3 April. The<br />

rate then dropped as the focus became airborne<br />

CAS in the Baghdad area. The last summary of<br />

cumulative weapon usage was given in the DoD<br />

briefing on Monday 7 April 59 , and marks the end<br />

of the intensive air campaign, relatively low<br />

weapons usage taking place <strong>for</strong> the final 12 days.<br />

What we are seeing, there<strong>for</strong>e, is an air campaign<br />

with four main elements: firstly counter-regime<br />

and WMD targets, which would have been classed<br />

as ‘strategic’ targets during Operation DESERT<br />

STORM; then counter-air operations; shaping<br />

operations; and finally direct and indirect support<br />

to the Land Component Commander. This, however,<br />

was not a sequential campaign, offensive air<br />

power being employed against all of these objectives<br />

with differing emphasis at differing stages of<br />

the campaign. The only really sequential elements<br />

were the initial attacks on the Baghdad Super MEZ