A Practical Guide to Action Research for Literacy Educators

A Practical Guide to Action Research for Literacy Educators

A Practical Guide to Action Research for Literacy Educators

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

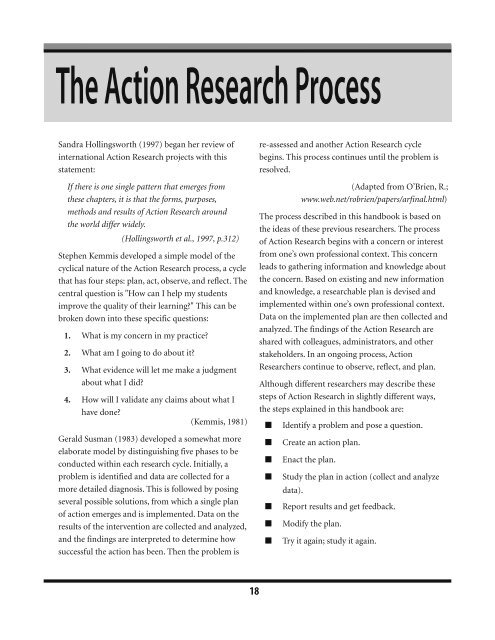

The <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Process<br />

Sandra Hollingsworth (1997) began her review of<br />

international <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> projects with this<br />

statement:<br />

If there is one single pattern that emerges from<br />

these chapters, it is that the <strong>for</strong>ms, purposes,<br />

methods and results of <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> around<br />

the world differ widely.<br />

(Hollingsworth et al., 1997, p.312)<br />

Stephen Kemmis developed a simple model of the<br />

cyclical nature of the <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> process, a cycle<br />

that has four steps: plan, act, observe, and reflect. The<br />

central question is "How can I help my students<br />

improve the quality of their learning?" This can be<br />

broken down in<strong>to</strong> these specific questions:<br />

1. What is my concern in my practice?<br />

2. What am I going <strong>to</strong> do about it?<br />

3. What evidence will let me make a judgment<br />

about what I did?<br />

4. How will I validate any claims about what I<br />

have done?<br />

(Kemmis, 1981)<br />

Gerald Susman (1983) developed a somewhat more<br />

elaborate model by distinguishing five phases <strong>to</strong> be<br />

conducted within each research cycle. Initially, a<br />

problem is identified and data are collected <strong>for</strong> a<br />

more detailed diagnosis. This is followed by posing<br />

several possible solutions, from which a single plan<br />

of action emerges and is implemented. Data on the<br />

results of the intervention are collected and analyzed,<br />

and the findings are interpreted <strong>to</strong> determine how<br />

successful the action has been. Then the problem is<br />

re-assessed and another <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> cycle<br />

begins. This process continues until the problem is<br />

resolved.<br />

(Adapted from O’Brien, R.;<br />

www.web.net/robrien/papers/arfinal.html)<br />

The process described in this handbook is based on<br />

the ideas of these previous researchers. The process<br />

of <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> begins with a concern or interest<br />

from one’s own professional context. This concern<br />

leads <strong>to</strong> gathering in<strong>for</strong>mation and knowledge about<br />

the concern. Based on existing and new in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

and knowledge, a researchable plan is devised and<br />

implemented within one’s own professional context.<br />

Data on the implemented plan are then collected and<br />

analyzed. The findings of the <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> are<br />

shared with colleagues, administra<strong>to</strong>rs, and other<br />

stakeholders. In an ongoing process, <strong>Action</strong><br />

<strong>Research</strong>ers continue <strong>to</strong> observe, reflect, and plan.<br />

Although different researchers may describe these<br />

steps of <strong>Action</strong> <strong>Research</strong> in slightly different ways,<br />

the steps explained in this handbook are:<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

Identify a problem and pose a question.<br />

Create an action plan.<br />

Enact the plan.<br />

Study the plan in action (collect and analyze<br />

data).<br />

Report results and get feedback.<br />

Modify the plan.<br />

Try it again; study it again.<br />

18