A Sourcebook - UN-Water

A Sourcebook - UN-Water

A Sourcebook - UN-Water

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

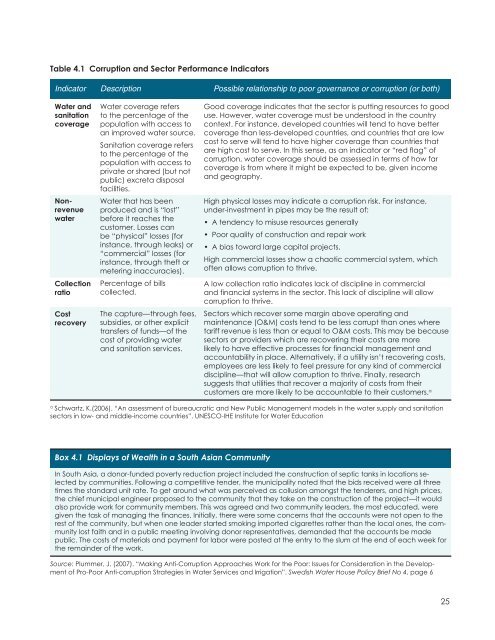

Table 4.1 Corruption and Sector Performance Indicators<br />

Indicator Description Possible relationship to poor governance or corruption (or both)<br />

<strong>Water</strong> and<br />

sanitation<br />

coverage<br />

Nonrevenue<br />

water<br />

Collection<br />

ratio<br />

Cost<br />

recovery<br />

<strong>Water</strong> coverage refers<br />

to the percentage of the<br />

population with access to<br />

an improved water source.<br />

Sanitation coverage refers<br />

to the percentage of the<br />

population with access to<br />

private or shared (but not<br />

public) excreta disposal<br />

facilities.<br />

<strong>Water</strong> that has been<br />

produced and is “lost”<br />

before it reaches the<br />

customer. Losses can<br />

be “physical” losses (for<br />

instance, through leaks) or<br />

“commercial” losses (for<br />

instance, through theft or<br />

metering inaccuracies).<br />

Percentage of bills<br />

collected.<br />

The capture—through fees,<br />

subsidies, or other explicit<br />

transfers of funds—of the<br />

cost of providing water<br />

and sanitation services.<br />

Good coverage indicates that the sector is putting resources to good<br />

use. However, water coverage must be understood in the country<br />

context. For instance, developed countries will tend to have better<br />

coverage than less-developed countries, and countries that are low<br />

cost to serve will tend to have higher coverage than countries that<br />

are high cost to serve. In this sense, as an indicator or “red flag” of<br />

corruption, water coverage should be assessed in terms of how far<br />

coverage is from where it might be expected to be, given income<br />

and geography.<br />

High physical losses may indicate a corruption risk. For instance,<br />

under-investment in pipes may be the result of:<br />

• A tendency to misuse resources generally<br />

• Poor quality of construction and repair work<br />

• A bias toward large capital projects.<br />

High commercial losses show a chaotic commercial system, which<br />

often allows corruption to thrive.<br />

A low collection ratio indicates lack of discipline in commercial<br />

and financial systems in the sector. This lack of discipline will allow<br />

corruption to thrive.<br />

Sectors which recover some margin above operating and<br />

maintenance (O&M) costs tend to be less corrupt than ones where<br />

tariff revenue is less than or equal to O&M costs. This may be because<br />

sectors or providers which are recovering their costs are more<br />

likely to have effective processes for financial management and<br />

accountability in place. Alternatively, if a utility isn’t recovering costs,<br />

employees are less likely to feel pressure for any kind of commercial<br />

discipline—that will allow corruption to thrive. Finally, research<br />

suggests that utilities that recover a majority of costs from their<br />

customers are more likely to be accountable to their customers. a<br />

a<br />

Schwartz, K.(2006). “An assessment of bureaucratic and New Public Management models in the water supply and sanitation<br />

sectors in low- and middle-income countries”. <strong>UN</strong>ESCO-IHE Institute for <strong>Water</strong> Education<br />

Box 4.1 Displays of Wealth in a South Asian Community<br />

In South Asia, a donor-funded poverty reduction project included the construction of septic tanks in locations selected<br />

by communities. Following a competitive tender, the municipality noted that the bids received were all three<br />

times the standard unit rate. To get around what was perceived as collusion amongst the tenderers, and high prices,<br />

the chief municipal engineer proposed to the community that they take on the construction of the project—it would<br />

also provide work for community members. This was agreed and two community leaders, the most educated, were<br />

given the task of managing the finances. Initially, there were some concerns that the accounts were not open to the<br />

rest of the community, but when one leader started smoking imported cigarettes rather than the local ones, the community<br />

lost faith and in a public meeting involving donor representatives, demanded that the accounts be made<br />

public. The costs of materials and payment for labor were posted at the entry to the slum at the end of each week for<br />

the remainder of the work.<br />

Source: Plummer, J. (2007). “Making Anti-Corruption Approaches Work for the Poor: Issues for Consideration in the Development<br />

of Pro-Poor Anti-corruption Strategies in <strong>Water</strong> Services and Irrigation”. Swedish <strong>Water</strong> House Policy Brief No 4, page 6<br />

25