You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

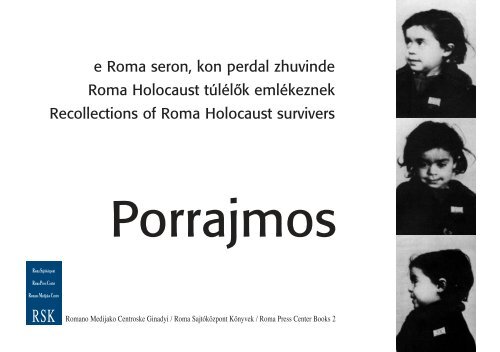

e Roma seron, kon perdal zhuvinde<br />

Roma <strong>Holocaust</strong> túlélők emlékeznek<br />

Recollections of Roma <strong>Holocaust</strong> survivers<br />

Porrajmos<br />

Romano Medijako Centroske Ginadyi / Roma Sajtóközpont Könyvek / Roma Press Center Books 2

Ála trájin le bácskake roma,<br />

le sztrémoszke mudárde pe droma, hej?<br />

Déta, Jankó, ker i bári milá,<br />

ke pa sáve haj e terni romnya, hej!<br />

Ále nyámco le báre bombanca,<br />

ájo ruszo le bute tankenca, hej!<br />

Puske báson, le savóra násen!<br />

Szosztár básen? Ke zorálesz básen, hej!<br />

Ávoj, Hitler, ásol tye séresztár!<br />

Szo tu kerdan amáre themesztár, hej!<br />

De m palpále mure ternyita<br />

ke prahon pe e csorre savóra, hej!<br />

Ávoj, Hitler, puter tri kapuva,<br />

ke prahon pe e csorre savóra, hej!<br />

Élnek-e a bácskai cigányok?<br />

Veszprémiek meghaltak az úton, hej!<br />

Sírjál, Jankó, bucsuzzál el sírva<br />

kedvesedtôl, kicsi fiadtól, hej!<br />

Jön a német nehéz bombázókkal,<br />

itt a ruszki dübörgô tankokkal, hej!<br />

Puska dördül, a gyerekek futnak!<br />

Miért futnak? Fegyverek ropognak, hej!<br />

Hej, te Hitler, pusztuljon a fejed!<br />

Országunkat pusztasággá teszed, hej!<br />

Elraboltad tôlem ifjuságom,<br />

megöltétek ártatlan családom, hej!<br />

Hej, te Hitler, nyisd ki a kapudat,<br />

most temetik kicsi fiamat, hej!<br />

Erdôs Kamill gyûjtése, Bari Károly fordítása

e Roma seron, kon perdal zhuvinde<br />

Roma <strong>Holocaust</strong> túlélők emlékeznek<br />

Recollections of Roma <strong>Holocaust</strong> survivers<br />

Porrajmos

1092 Budapest, Ferenc krt. 22. 2/3., Hungary<br />

Tel.: (36-1) 217-1059, tel./fax: 217-1068<br />

E-mail: romapres@elender.hu<br />

http://www.romapage.c3.hu/rskhir.htm<br />

O Romano Medijako Centro kathar o<br />

l995 kidel kethane thaj del avri nyevi -<br />

penge sakodi, so le romenca peci sajvel<br />

ando Ungriko Them.<br />

Tala panzh bersh kade oxto shel skurto<br />

thaj lungo iskirimo dine avri le ung -<br />

rika nyevipura. Panzh shel radio shicko<br />

butyi dine tele le Ungriko Themesko<br />

radiovura. Ande amare bu tyi butivar<br />

rakhadyilam kasave historijenca, saven<br />

aba na ande nyevipura trubulas te das<br />

avri. Ande kade, kade kamas, te keras ke<br />

majbut ginadyi, te das avri, ande sos te<br />

tele iskirisaras so pecisardas dulmut, thaj<br />

akanak- andar kodolengo muj, kasa<br />

kasave pecisarde. Kodol kon keren e<br />

ginadya kodi ka men ke le roma phenen<br />

lenge historije pala pende, na kaver te<br />

phenel. Le rom butivar kodole histo rije<br />

phenena, save inke khonyik chi push las<br />

lendar.<br />

Najis tumenge, ke zhutisaren amenge<br />

ke kadal historije avri te das:<br />

A Roma Sajtóközpont 1995 óta dol -<br />

goz za fel és adja közre a sajtóban a Ma -<br />

gyarországon és a régióban élô ro ma<br />

kö zö sségekkel kapcsolatos ese mé nye -<br />

ket. Az indulás óta eltelt öt évben mintegy<br />

nyolcszáz rövidhírünket és hosz -<br />

szabb cikkünket közölték magyar or szá -<br />

gi napilapok, félezer rádiós anyagunkat<br />

sugározták magyarországi rá diók. Mun -<br />

kánk során azonban több olyan törté -<br />

nettel találkoztunk, amelyek feltárása és<br />

dokumentálása szétfeszítik az újságírás<br />

ha gyományos ke reteit: ezért döntöttünk<br />

úgy, hogy a jövôben könyvsorozat<br />

formájában je len tetjük meg a közelmúlt<br />

és a jelen sür getôen feldolgozatlan ese -<br />

ményeit – az azokat átélôk szájából. A<br />

szer kesz tôk szándéka szerint e könyv -<br />

sorozat lapjain a romák, ahelyett, hogy<br />

róluk mesélnének, maguk fogják elme -<br />

sélni a legtöbb esetben elôtte soha meg<br />

nem kérdezett történeteiket.<br />

Köszönjük, és hálásak vagyunk, hogy<br />

segítenek nekünk e történetek köz re -<br />

adásában:<br />

The Roma Press Center has been<br />

recollec ting and publishing all issues<br />

regarding the Romani community in<br />

Hungary and in the region since 1995.<br />

Since its inception, in the past 5 years,<br />

well over 800 short news items and<br />

longer articles written by our staff were<br />

published in Hungarian national newspapers,<br />

as well as 500 radio programs of<br />

the Roma Press Centre were aired in<br />

several radio stations in Hungary. In the<br />

past five years we have found several<br />

stories where the investigation and do -<br />

cumentation would have broken the<br />

frames of the traditional journalism; so<br />

we decided to start publishing the most<br />

unexplored issues of the present and<br />

the recent past in the form of a book<br />

– through the authentic narration of the<br />

ones who went through them. According<br />

to the intention of the editors, on the<br />

pages of these books Roma will tell their<br />

stories – most of them never told before<br />

–, instead of being subject of the narration.<br />

We are grateful to the following people<br />

for telling their stories:<br />

1. Puczi Béla (Marosszentgyörgy–Budapest)<br />

2. Krasznai Rudolfné Kolompár Friderika, Lendvai Ilona, Holdosi Vilmosné, Bogdán Ilona, M. M.-né, Kovácsi Gyuláné<br />

Kolompár Matild, Kolompár Istvánné Lakatos Julianna, Raffael Ilona, Vajda Rozália, Hódosi Magdolna, Sztojka Istvánné,<br />

Krasznai Rudolf, Oroszi Rudolf, Holdosi József, Kánya Lajos, Bognár Albert, Szemerei András, Peller Piroska,<br />

Rakovszki Miklósné, Raffael Margit, Lakatos Angéla<br />

3. ...........<br />

4. ...........

Porrajmos<br />

e Roma seron, kon perdal zhuvinde<br />

e Roma<br />

Roma<br />

szeren,<br />

<strong>Holocaust</strong><br />

kon<br />

túlélők<br />

perdál<br />

emlékeznek<br />

zhuvinde<br />

Recollections Roma <strong>Holocaust</strong> of Roma túlélôk <strong>Holocaust</strong> emlékeznek survivers<br />

Recollections of Roma <strong>Holocaust</strong> survivers<br />

editor/szerkesztette/edited by: BERNÁTH GÁBOR<br />

kon phushenas/az interjúkat készítették/interviews were made by: DR. BÁRSONY JÁNOS, DARÓCZI ÁGNES, H ORVÁTH ÉVA,<br />

HORVÁTH MARGIT, LAKATOS ELZA, MÁRVÁNYI PÉTER<br />

(MÁRVÁNYI S. GYÖRGY), MIKLÓSI GÁBOR,<br />

NÓTÁR ILONA, PUCZI BÉLA, S. KÁLLAI SZILVIA,<br />

TRENCSÉNYI KLÁRA, VIDÁK MELINDA, ZSIGA ALFONZ<br />

boldas/fordította/translated by: RADNÓTI ANNA (anglicko shib/angol/English),<br />

MOHÁCSI JÓZSEFNÉ és MOHÁCSI EDIT (romanes)<br />

naisaras/külön köszönet/special thanks to: DR. BÁRSONY JÁNOS, DARÓCZI ˇ ÁGNES, MAJOROS ˇ KLÁRA,<br />

CLAUDE CAHN, SARITA JASAROVA, SEJDO JASAROV,<br />

LAKATOS ELZA, ANNE LUCAS, SERGE MEZHBURD,<br />

MOHÁCSIVIKTÓRIA, ZÁDORI SAMU<br />

fotovura/képek/pictures: DOKUMENTATIONS- UND KULTURZENTRUM<br />

DEUTSCHER SINTI UND <strong>ROMA</strong>;<br />

INTERNATIONAL AUSCHWITZ COMMITTEE<br />

Sponsor<br />

A könyv megjelenését támogatta<br />

The publication has been supported by: ROYAL NETHERLANDS EMBASSY IN BUDAPEST

ISSN 1585 - 8901<br />

ISBN 963 00 3889 7<br />

Roma Sajtóközpont Könyvek 2<br />

Budapest, 2000<br />

© Roma Sajtóközpont, Jancsó Miklós, Daróczi Ágnes,<br />

dr. Bársony János, Márványi Péter,<br />

Dokumentations- und Kulturzentrum<br />

Deutscher Sinti und Roma;<br />

International Auschwitz Committee<br />

Kiadja a Roma Sajtóközpont<br />

A kiadásért felel: a Roma Sajtóközpont igazgatója<br />

Tördelés: EZ<br />

Nyomás: Rózsa Nyomda<br />

Felelôs vezetô: Rózsa Gábor

Tartalomjegyzék<br />

MICHAEL STEWART:<br />

Serojipo thaj serosaripo<br />

Emlékezet és megemlékezés<br />

Memory and Commemoration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

Sar shavoro/Gyerekfejjel/As a child . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

Sheja/Lányok/Young girls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56<br />

Terne Roma/Férfiak/Young men . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95<br />

Kodol romenge anava kon mule ando butyano lageri<br />

Roma munkaszolgálatos áldozatok névsora<br />

List of Roma Victims of the Forced Labor Service . . . . . . . . . . .123<br />

Tela phuv/Föld alatt/Under the sod . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .127<br />

Porrajmos ando Ungriko Them-Kronologija<br />

A Porrajmos Magyarországon-Kronológia<br />

Porrajmos in Hungary-Chronology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .137<br />

Porrajmos ande Trito Imperija-Kronologija<br />

A Porrajmos a Harmadik Birodalomban-Kronológia<br />

Porrajmos in the Reich-Chronology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .146

SEROJIPO THAJ SEROSARIPO<br />

– MICHAEL STEWART –<br />

EMLÉKEZET ÉS MEGEMLÉKEZÉS<br />

– MICHAEL STEWART –<br />

MEMORY AND COMMEMORATION<br />

– MICHAEL STEWART –<br />

Else Schmidt efta bershengi sas, kana 1942 de milaj<br />

kheral ingerde la andar o Hamburgo. Pe kode seroj,<br />

duj ketana ingerde la ande ek porticko baro kher, kaj<br />

le but romen khidenas khetane. La Elseka chi gindonas<br />

pala kode sostar, ande la khate. Inke chi kode<br />

na zhanglas sosi kodo „rom”. Chi vreme nas la, te<br />

zhanel sosi o rom, ke lako dad sigo rakhas la, haj<br />

khere ingerdas la. Kattyi phendas lake, te bistrel o<br />

intrego.<br />

E Else – atunchi inke na zhanglas – laki dej<br />

„doppash rom” sas, lako dad nyamco sas. O naci terminologica<br />

avri phenel voj „C-minus” si. Kadal<br />

kasave manusha si, kasko rat hamisardyol le nyamcicko<br />

ratesa. Le kasave manusha le maj bare benga.<br />

Le „uzhe roma” kodol barem andar mashkar jekha -<br />

ver len romnya, haj romes. Le „C-minusosa” pale<br />

and re makhen le uzhe nyamcengo patyiv. La Elseka<br />

bax sas: ke voj ando trajo ashilas, maj anglal sar lake<br />

da deportalisarde, jekh nyamcicko familija garudas la,<br />

pala kode pasha peste las la. Cinyi sas inke atunchi,<br />

haj anda kode na serosajvel.<br />

Else Schmidt hétéves volt, amikor 1942 nyarán el -<br />

vitték hamburgi otthonából. Arra emlékszik, hogy két<br />

katonaruhás férfi bekísérte egy kikötôi raktárépületbe,<br />

ahová már cigányok tömegét gyûjtötték be. Elsének<br />

sejtelme sem volt arról, hogy miért hozták ide.<br />

Valójában azt sem tudta mi az, hogy „cigány”.<br />

Ezúttal esélye sem volt arra, hogy megtudja, mivel az<br />

apja órákon belül rátalált, és hazavitte. Annyit mondott<br />

neki, hogy félreértés történt, és felejtse el az<br />

egészet.<br />

Else – bár akkor még ezt nem tudta – „félcigány”<br />

anya lánya volt, aki nem cigány árjához ment fele sé -<br />

gül. A náci terminológia szerint így a „C-mínusz”<br />

kategóriába számított, amely kevert fajú cigányt je -<br />

len tett, háromnegyed részben német vérrel. Az efféle<br />

keveréket veszélyesebbnek tartották, mint az ún.<br />

„tisz ta cigányokat”, mert azok legalább egymás kö -<br />

zött házasodtak. A „C-mínuszosok” azonban be -<br />

sze nnyezéssel fenyegették az árja közösséget. El sé -<br />

nek szerencséje volt: túlélte az üldözést, mert nem<br />

sokkal édesanyja deportálása elôtt elbújtatta, majd<br />

Else Schmidt was seven years old when taken in the<br />

summer of 1942 from her home in Hamburg. She<br />

remembers two men in military coats marching her to<br />

a warehouse on the docks where they left her among<br />

crowds of Gypsies already gathered there. Else had no<br />

idea why she had been brought there. In fact, she had<br />

no idea what a ‘Gypsy’ was. Nor, on this occasion,<br />

did she have a chance to find out, for within hours her<br />

father had found her and brought her out of the docks.<br />

He told her that there had been a misunderstanding<br />

and that she should forget all about it.<br />

Else – though she did not know it then – was the<br />

daughter of a ‘half-Gypsy’ who had married a<br />

non-Gypsy Aryan. As such, she counted in Nazi terminology<br />

as a ‘Z minus’, a mixed-race Zigeuner<br />

with ‘a greater proportion of German blood’. Such<br />

mischlinge were seen as more of a menace than the<br />

so-called ‘pure Gypsies’ because these latter at least<br />

‘married amongst themselves.’ Z minuses, by<br />

contrast, threatened to pollute the ‘folk community’.<br />

Else, then had already been rather fortunate in<br />

7

Pala duj bersh pale palpale avile le duj manusha.<br />

„Muro na chacho dad gindyindas, aba na but shaj<br />

kerel mishto, avla te phenla mange o chachipo.<br />

Atuhchi phendas mange na voj muro chacho dad. Vi<br />

leski romnyi thaj vi voj zurales rovnas. Thaj phendas<br />

mange muri na chachi dej, kaj akanak zhas, kothe<br />

rakhadyuves kodola romnyasa, kon si tyi dej. Me chi<br />

hatyardom andar kade khanchi… Pe kode pale<br />

mishto seroj, kanak cini shej somas thaj kanak<br />

zhamas varikaj, so le dujzhene xutyelnas mure vast,<br />

te na mukhas jekhekavres.<br />

Uzhes seroj pe kode kana te xutrav jekh geshtaposhesko<br />

vast haj voj shudas muro vast. Pe kadal mishto<br />

seroj desar shavoro but resnas mange de cini so<br />

pecisajvel manca.<br />

Elsake bari baxt sas, na kade sar kodole butshel mijje<br />

romenge kas andar 1936 thaj mashkar o 1945-o<br />

ingerde andar lengo kher. Lako na chacho dad inke<br />

jokhar las peske o tromipo, thaj gelas kaj o SS-i te<br />

mangel lake slobodicko lil. Pala panzh shon, pala<br />

kode sar ingerde la, tele gelas ando Ravens brücko te<br />

ingrel la khere.<br />

Else ando Londoni ando Imperial War Museumoske<br />

phendas, na dulmut kode mangle latar kana ando<br />

lageri sas, so lasa kerde kothe, pala kode te na vorbil<br />

khanchi thaj te iskiril telal jekh hertija, so maladyilas<br />

lasa ando Auschwitzo. Kado papiroshi na reslas<br />

khanchi. „Ke kon bararnas man, ande Hamburga<br />

trajinas khanchi na zhannas pala kode, so pecisajlas<br />

ando lageri. Kattyi gindyinas numa nasul shaj sas<br />

kothe. Kode chi zhangle sar mudaren thaj phabaren<br />

le manushen. Chi na hatyarde pe sosko pharipo<br />

8<br />

adoptálta egy német család, és túl kicsi volt ah hoz,<br />

hogy vissza tudjon emlékezni azokra az idôk re.<br />

Két évvel a zavarba ejtô kikötôi kaland után ismét<br />

megjelent náluk a két férfi. „A nevelôapám úgy gondol<br />

ta, hogy ezúttal nem lenne olyan könnyû kihoznia<br />

onnan, ezért elmondta nekem, hogy ô nem a vér -<br />

szerinti apám, és sírt, amikor errôl beszélt. Az anyu -<br />

kám pedig könnyezve mondta el, hogy nem mi<br />

vagyunk az igazi szüleid. Ahová most kerülsz, ott<br />

találkozni fogsz az igazi mamáddal. Engem teljesen<br />

felkészületlenül ért mindez, egyszerûen nem értettem<br />

az egészet… Vannak részletek, amelyekre külö nö sen<br />

jól emlékszik az ember a gyerekkorából. Pél dául<br />

mindig kézen fogva vezettek a nevelôszüleim, hogy el<br />

ne veszítsük egymást.<br />

Tisztán emlékszem, hogy meg akartam fogni az<br />

egyik gestapós kezét, de ô ellökte a kezemet. Na gyon<br />

jól emlékszem ezekre az apróságokra, mert ak kor<br />

gyerekként ezek nagyon sokat jelentettek nekem.”<br />

Else szinte példátlanul szerencsés volt azokhoz a<br />

ci g ány származású százezrekhez képest, akiket<br />

1936 és 1945 között elhurcoltak az otthonukból<br />

vagy a sátortáborukból. Nevelôapja az elsô sikeres<br />

közbelépés után még egyszer vette a bátorságot, hogy<br />

menlevelet kérjen az SS-tôl a kislánynak. Öt hó nappal<br />

Else elhurcolása után Ravensbrückbe utazott,<br />

hogy hazavigye.<br />

Else a londoni Imperial War Museum által nemrégiben<br />

rögzített visszaemlékezésében elmondta, hogy<br />

utoljára azt követelték tôle a táborban, írjon alá egy<br />

papírt, amelyben vállalja, hogy senkinek nem beszél<br />

surviving, hidden in a German family where she had<br />

been adopted some time before her biological mother<br />

had been deported. She herself had been too young to<br />

remember any of this.<br />

Two years after her first puzzling visit to the docks,<br />

the men came to the door again. ‘My adoptive father<br />

thought it would not be so easy this time to get me<br />

back, and so he told me I was not his biological child;<br />

he cried when he said this. And my mother said<br />

through her tears, “we are not your real parents. You<br />

will meet your real mother at the place where you are<br />

going now.” I was completely unprepared for all this<br />

and I just could not understand it…. There are<br />

details which you particularly remember as a child.<br />

For instance, I had always held hands with my adoptive<br />

parents when walking so as not to get lost. I can<br />

clearly remember that I looked for the hand of one of<br />

the Gestapo for me to hold, but he pushed my hand<br />

away. These are small things which I can remember<br />

quite clearly, because for me as a child they were big<br />

things.’<br />

Amongst the hundreds of thousands of people of<br />

Gypsy descent who were taken away from their<br />

homes and caravans between 1936 and 1945 Else<br />

was almost uniquely fortunate. Her adoptive father,<br />

having succeeded once, braved the offices of the SS<br />

again and secured letters of release. Five months after<br />

she was taken away he travelled to Ravensbrück to<br />

reclaim her.<br />

In a recent interview carried out by London’s Imperial<br />

War Museum, Else explained that her last obligation<br />

in the camp was to sign a paper in which she under-

gelom perdal, anda jekh palpale trade man ande<br />

shkola. Kon barardas man na mishto kerde aba pala<br />

kodo naj keren.”<br />

Khere chi vorbinnas pala e nasulyipo. Ande shkola<br />

pale sa lazhavo kernas lake. „Ke ando lageri kothe<br />

sas pe muri kuj o billogo, ande shkola sa tele trubulas<br />

te sharavav muri kuj. Ande shkola ande anglune<br />

dyesa le sittyara nasul nacivura sas le, opre tordyarde<br />

man, thaj kode phende: zhikaj na phenes avri sako -<br />

neske, so si pe tyi kuj, zhi pe atunchi si te tordyos<br />

kathe.”<br />

Zhi kathar deshoxto bersh khonyik na vorbisardas la<br />

Elsasa pala kode, so maladyilas lasa kana voj sas<br />

oxto-inje bershengi ando Auschwitzo, thaj ando<br />

Ravensbrücko.<br />

ottani tapasztalatairól, sem a korábban<br />

Auschwitzban történtekrôl. Valójában nem sok értel -<br />

me volt ennek a formális aláírásnak. „Hamburgban<br />

élô nevelôszüleimnek fogalmuk sem volt a koncentrációs<br />

táborokban uralkodó kegyetlen állapotokról. El -<br />

ismerték, hogy nagyon rossz lehet egy ilyen kény szermunkatábor,<br />

de azt elképzelni sem tudták, hogy ott<br />

kínozzák, gyilkolják, elégetik az embereket. Ezért<br />

meg sem értették milyen szörnyûségeken men tem<br />

keresztül, hanem egybôl visszaküldtek az isko lába.<br />

Ez persze nagy tévedés volt a nevelô szüleim részérôl,<br />

de nem tehettek róla.”<br />

Else szülei odahaza fátylat borítottak a kislány gyöt -<br />

relmeire. De az iskolában nyíltan folyt a megalázás:<br />

„Nagyon rossz emlékeim vannak az iskoláról, mivel<br />

a koncentrációs táborban rám tetovált szám még min -<br />

dig ott volt a karomon, csak egy ragtapasz takarta.<br />

Az elsô napon a tanárok, akik rémes nácik voltak,<br />

felállítottak az osztályban és azt mondták: Addig<br />

kell itt állnod, amíg el nem mondod mindenkinek,<br />

hogy mi van a ragtapasz alatt.”<br />

Ettôl fogva tizennyolc éven át Else senkivel nem be -<br />

szélt arról, mi történt vele 8-9 éves korában,<br />

Auschwitzban és Ravensbrückben.<br />

Ennek a hamburgi kislánynak a története megegye -<br />

zik a többi cigány túlélô élményeivel. A különbözô<br />

táborokból hazatérve rá kellett jönniük, hogy azt várják<br />

tôlük, hallgatással fizessenek azért, ha vissza<br />

akarnak térni otthonaikba, falvaikba, és városaikba.<br />

Hallgatniuk kell arról, hogyan üldözték, hogyan pró -<br />

bálták megsemmisíteni a népüket. Közkeletû fel fogás<br />

szerint ôk, az áldozatok a felelôsek az átélt<br />

Kadalake cina shake historija kasavi si, sar le<br />

majbute romenge historija, kon na mule kothe ando<br />

lageri. Kon khere avilas andar o lageri, sakode zhutyarnas,<br />

lendar te na phenen khanchi, te khere kamen<br />

te aven ande pengi gava. Chi pe kode nashtig phentook<br />

not to tell anyone of her experiences there or of<br />

her earlier stay in Auschwitz. But there was little<br />

need for the ritual of the signature. ‘My adoptive parents<br />

in Hamburg had no idea how cruel reality in the<br />

concentration camps was. They had accepted that there<br />

were very bad forced labour camps, but they could not<br />

imagine that people were ill-treated, murdered and<br />

burned there. So they could not understand the frightful<br />

things I had gone through, and so sent me straight<br />

back to school. After just two or three days at home I<br />

had to go to school again. Of course that was wrong<br />

of my adoptive parents, but they didn’t know any better.’<br />

Else’s parents drew a veil at home over her torment.<br />

Humiliation at school worked more brutally: ‘I have<br />

very bad memories of school, because I still had<br />

my concentration camp number tattooed on my arm<br />

with just a plaster to hide it. On the first day, the<br />

teachers, who were bad Nazis, forced me to stand up<br />

in class. They said to me: You must stand here until<br />

you have told everyone what is under the plaster.’<br />

From that day, for eighteen years, Else spoke with no<br />

one about what had happened to her in Auschwitz<br />

and Ravensbrück aged 8 and 9.<br />

This story of one Hamburg girl speaks to the experience<br />

of every Gypsy survivor. On returning from<br />

the camps, they found they were expected to pay for<br />

re-admission to their homes, villages and towns with<br />

silence about their exile and the attempted destruction<br />

of their people. Commonly it was they, the victims,<br />

who were blamed for their own suffering, labelled as<br />

criminals or ‘asocials’. While such convenient forget-<br />

9

nas khanchi sar nashavnas len thaj sar kamne te<br />

mudaren lenge nipon. Le majbut manusha kade xut -<br />

ren opren godyasa, kas ingerde von shaj shon pala<br />

kode, sostar rakhadyile romenge thaj bi boldenge, ke<br />

kadal sa doshale sile. Le majbut manu sha sigo bisterde<br />

so kerde le manushenca thaj chi phennas khan chi<br />

kanak ingernas len. Le roma pale na zhanen te<br />

bistren so kerde lenca.<br />

Elseke lindri inke vi akanak palpale aven kodol but<br />

nasulyipe, so atunchi ando lageri na hatyarlas. „Ko -<br />

the pashljonas le parne mule, tele shordime parno<br />

mesosa, pe jekhekavreste shudime. Sar shavoro chi<br />

opre na xutyildom so si kodol. Inke vi majpalal aba -<br />

kanak khere avilom butivar domas suno kodolenca so<br />

kothe dikhlom: kothe ashav ando Hamburgo, angla<br />

forosko kher, thaj kon pasha mande tordyon manu sha<br />

kode phenen, lenca si te zhav. Me phenav, na zhanav<br />

te zhav, ke e phuv pherdo si mulenca. Le majbut<br />

manusha chi dikhen ande muri lindri le mu len, von<br />

perdal zhan pe lende, chi dikhen khanchi.”<br />

Else Schmidt numa kade slobisardas kathar leski<br />

nasul lindri, ke avri gelas ande Anglia, pala peste<br />

mukhlas kodo luma, kanak shavoro sas. Le majbut<br />

rom ande Europa na zhanglas te bistrel so pecisardas<br />

lesa. Le bute romen chi ashundas khonyik, lengo<br />

lungo phari butyi,thaj kadi mirgisarel lengi trajo.<br />

Kanak jekh intrego them kamel te bistrel pesko na -<br />

chipo, thaj avri kamel te khosel le manushengi serojipe,<br />

atunchi vi kodo them kasavo kerdyol, sar kodol<br />

manusha kon perdal trajinde le nasulyipe. So avla<br />

kodolesa themesa savo chi mukhel le manu shenge, te<br />

seron pe nasulyipe, savo ande manusha tasavel le<br />

10<br />

szenvedésekért, ôket címkézték bûnözôknek, és<br />

„aszo ciális” elemeknek. Milyen könnyen jött a jó -<br />

tékony feledékenység azoknak, akik szó nélkül néz -<br />

ték végig, hogyan hurcolják el a szomszédaikat, mi -<br />

közben a cigányok korántsem tudták ilyen egysze -<br />

rûen elfelejteni szenvedéseiket.<br />

Else álmaiban még évek múlva is visszatérnek azok<br />

az események, amelyeket akkor, a táborban nem értett<br />

meg. „Ott feküdtek a fehér holttestek, beszórva fehér<br />

mésszel, egymás hegyére-hátára dobálva. Gye rekként<br />

fel sem fogtam, hogy mik azok. De jóval késôbb,<br />

évekkel a kiszabadulásom után lidérces álmokban<br />

megjelent ez a szörnyû látvány: ott állok<br />

Hamburgban a városháza árkádja alatt, és a körülöttem<br />

lévô emberek azt mondják, hogy velük kell mennem.<br />

De én azt felelem, nem tudok menni, mert a<br />

föld tele van holttestekkel. De a többiek az álmomban<br />

nem látják a halottakat; egyszerûen átsétálnak<br />

rajtuk a magas sarkú cipôjükben, és nem vesznek<br />

tudomást a holttestekrôl.”<br />

Else Schmidt csak úgy szabadulhatott a rémálmaitól,<br />

hogy elmenekült elôlük Angliába, maga mögött hagyva<br />

gyermekkora világát. De az európai cigányok<br />

többségének nem sikerült megszöknie a múlt szinte<br />

tapintható emlékeitôl.<br />

A soha meg nem hallgatottak hosszúra nyúlt szen -<br />

vedései megmérgezik az életüket. De amikor egy<br />

egész társadalom próbálja meg nem történtté tenni a<br />

múltját, kitörölni egyes tagjainak kínzó emlékeit,<br />

akkor bizonyos értelemben maga a közösség lesz fertôzött.<br />

Mi lesz egy társadalom emlékezetével, ha<br />

megtagadja, tiltja, vagy elfojtja a megemlékezést egy<br />

fulness slipped easily into place for those who had<br />

stood by and watched their neighbours deported, the<br />

Gypsies suffering could not simply be willed out of<br />

consciousness.<br />

Years later, Else would dream of things she had not<br />

understood at the time in the camps.‘There were<br />

white corpses sprinkled with white lime, all piled on<br />

top of each other. As a child, I just could not understand<br />

what it was. Very much later, years after my liberation,<br />

I had awful nightmares about this sight: that<br />

I am standing under the portal at the city hall in<br />

Hamburg, and the people standing next to me are<br />

saying to me I should come with them. But I say “no,<br />

I cannot walk on the ground, the whole floor is full of<br />

corpses.” But the other people in the dream cannot see<br />

the dead; they just walk over them with their high<br />

heeled shoes and take absolutely no notice of the<br />

corpses.’<br />

Else Schmidt only escaped her nightmares by fleeing<br />

to England and leaving the world of her childhood<br />

behind her. Most of Europe’s Gypsies have had less<br />

success getting away from the tangible reminders of<br />

the past.<br />

The enduring suffering of those who have never been<br />

properly heard blights the lives of those individuals.<br />

But when a whole society tries to ignore its past<br />

and paint out the pain of some of its members then<br />

the collective is in some sense stained. What happens<br />

to the memory of a society when commemoration of<br />

trauma is denied, forbidden or suppressed? There is<br />

surely no single answer to this question. Just as individuals<br />

organise and access the past in different ways,

serojipe? Pe kado pushipo nashtig te phe nas khanchi.<br />

Sar vi ande kodi si differencija sar seron le manusha<br />

po nachipo, vi anda kodi si differencija sar le kulturi<br />

losaren po nachipo, po serojipo, thaj sar ingren perdal<br />

o nachipo ande amare dyesa. Le roma sar te kethane<br />

vorbisardenas, bistren o Porrajmoshi, numa ande pen -<br />

ge godyi losaren pe penge serojipe. Losaripo thaj bistraripo<br />

kado baro paradoxo si, kado trubulas te kerel<br />

o porrajmoshesko rodipo-jekh themesko nipo trubulas<br />

te pinzharel pesko nachipo, jekh themesko nipo kas<br />

naj shkoli, thaj naj les medija, kado nipo trubulas te<br />

kethane phandel le adyesesko dyes le aratyako dyesesa.<br />

(…)<br />

súlyos traumájáról? Erre a kérdésre bizonnyal nem<br />

adható egyetlen válasz. Ahogy az egyének is különbözôképpen<br />

kezelik, és közelítik meg a múltat, úgy<br />

a kultúrák is eltérô módon viszik át a múltat a<br />

jelenbe. Mintha a cigányok egy emberként össze es -<br />

küdtek volna, hogy elfelejtik üldöztetésük trau má ját,<br />

egyszersmind némán bár, de megôrzik a rejtett kol -<br />

lektív emlékezetben. Megôrzésnek és felejtésnek ez a<br />

paradox párban állása az, amelyet felszínre kell hoznia<br />

a roma holokausztkutatásnak – ez volna a<br />

módja annak, hogy egy ország, iskolák, saját média<br />

nélkül élô népe megismerje és összekapcsolja a jelenét<br />

a múltjával. (…)<br />

so too cultures have multiple ways of placing the past<br />

in the present. At one and the same time the Gypsies<br />

conspire to forget the trauma of their persecution and<br />

to hold on – though in silence – to a hidden, collective<br />

memory of it. It is this paradoxical combination,<br />

of retention and amnesia which an investigation of<br />

the Romany holocaust has to explore – seeing in it<br />

the means found by a people without a state, without<br />

schools, or control of their own media to know and<br />

place their present in relation to their past. (…)<br />

11

Sar shavoro<br />

Gyerekfejjel<br />

As a child<br />

13

„Kanak avri gelam ando Auschwitzo, ando<br />

injevardes thaj starto vaj panzsto bers, ando<br />

augustuso, po dujto gyes, atunchi raklam<br />

muri dadesko anav,<br />

avri sas le but anava pala jekhekavreste<br />

iski rime. (…) Zhanglam ke ando<br />

Nyamcicko them ingerde len, numa kodi<br />

na zhanglem kaj. (…) Te na xutyilel man<br />

jek fehérvarisko rom, avri kamlom te lav<br />

jek kotor, gingyindom: khere lingrav. Kodi<br />

phendas muro shavo, o Józsi:<br />

Mama na inzu andre, ke shaj xutyiles nasvalyipo.<br />

Na bunij me, muro shavo – phendom.<br />

Kathar zhanes tu tye phralesko sas,<br />

tye dadesko sas! Atunchi nasules kerdyilom,<br />

avri ingerden man kathar o<br />

phabaruno.”<br />

Krasznai Rudolfné, Kolompár Friderika<br />

But zhene chudinpe, kana pala deportalashi<br />

pushen ma, sar zhanav te seroj palpale, atunchi<br />

somas numa deshuduj bershengo. Te pushesas<br />

mandar so kerdom aratyi, na zhanav te phenav<br />

tuke. De kana atunchi maladyilas, sako felo ando<br />

muro shero si. Shajke vas muro guglo dad seroj<br />

pe sako felo. Tranda thaj shov bershengo sas,<br />

kana ingerde les. Ando shtarvardesh taj shtar,<br />

novembr trin, detehara krujal khutyilde le<br />

romengo pero le shingale. Kaj sako kher tordyilas<br />

jekh, haj andre chingarel: ushtyen opre len<br />

pe tume le gada, son tumenge pe trin dyes xapo,<br />

haj ashen pekhaver! Muro choro dad kode<br />

phendas: shavorrale, gata amenge! Muri chori<br />

dej rolyindo shudas dujende amare gada, so sigo<br />

14<br />

„Apámat akkor találtuk meg,<br />

amikor Auschwitzba kimentünk,<br />

kilencvennégy vagy kilencvenötben,<br />

augusztus másodikán. Egy nagy táblán volt<br />

a nevük sorba, végig. (…)<br />

Tudtuk, hogy Németországba vitték ôket,<br />

csak azt nem, hogy hová. (…)<br />

Ha egy fehérvári cigány ember nem kap el,<br />

én benyúlok a kemencébe, és kiveszek egy<br />

darabot, gondoltam: kiveszem és<br />

hazahozom emléknek. Azt mondja erre a<br />

Józsi fiam: anyám, ne nyúljál bele, mert fertôzést<br />

kaphatsz. Nem bánom én<br />

fiam – válaszoltam. Honnan tudod,<br />

hogy a testvéredé vagy az apádé volt<br />

– kérdezett vissza. Elájultam, kivittek<br />

az égetôbôl.”<br />

Krasznai Rudolfné, Kolompár Friderika<br />

Sokan csodálkoznak, amikor a deportálásról<br />

kér deznek, hogy tizenkét éves koromban hogy<br />

tudtam így mindent megjegyezni. Ha azt kér -<br />

deznéd, hogy tegnap mit csináltam, nem tud -<br />

nám megmondani. De ami akkor történt, minden,<br />

pontról-pontra megvan a fejemben. Talán<br />

édesapám miatt emlékszem annyira mindenre.<br />

Harminchat évesen vitték el. Negyven négy ben,<br />

november harmadikán, hajnalban, körülfogták a<br />

cigánytelepet a csendôrök. Minden ház hoz<br />

odaállt egy, és bekiabált: ébresztô, mindenki keljen<br />

föl, öltözzön, három napi élelmet pakoljunk<br />

be, sorakozó! Szegény apám azt mondta: na,<br />

gyerekeim, végünk van! Szegény anyám sírva<br />

pakolta be két batyuba a motyón kat, amit<br />

‘We found my father when we went to<br />

Auschwitz on the second of August in<br />

ninety-four or ninety-five. Their names<br />

were written on a big slab one after the<br />

other. (…) We knew that they had taken<br />

them to Germany but we did not know<br />

where. (…) If a Rom from Fehérvár had<br />

not caught me, I would have reached into<br />

the oven and taken a piece out of it.<br />

I thought, I would take it out and bring it<br />

home as a reminder. Then my son Józsi said<br />

to me: ’Mother, don’t touch it ’cos you’d<br />

get a disease.’ ’I don’t care, son!’ – I<br />

replied. ’How do you know whether it was<br />

your brother’s or your father’s?’ – he asked.<br />

I fainted and they took me out of the crematorium.’<br />

Friderika Kolompár, Mrs. Rudolf Krasznai<br />

When they ask me about the deportation, many<br />

are surprised that at the age of twelve<br />

I could memorise everything so well. If you ask<br />

me what I did yesterday afternoon I could not<br />

tell. But I remember everything that happened<br />

then, I have it in my mind point by point.<br />

Probably, it is because of my father that<br />

I remember so many things. They took him<br />

when he was thirty-six. On the 3rd of<br />

November, 1944 at dawn, the gendarme patrols<br />

surrounded the Romani settlement. There was<br />

a patrol for each house, who shouted in: ‘Wake<br />

up! Everybody, get up, dress up and pack food<br />

for three days! Line up!’ My poor father said:<br />

‘My children, we are finished!’ My poor moth-

zhanglas. Tele ingerde ame kade sar jekh haj<br />

doppash kilometeri, ando Bak, sa desh taj shov<br />

familija, sar sheltajbish manushen. Na mukhne<br />

chi jekh manushes.<br />

Ando Bak le mujalesko avlyin beshlam<br />

shindyolas o brishind, zhikaj pala mizmeri, pala<br />

kode gelam ande punre zhikaj e Zalaegerszega,<br />

khote andre shude amen jekh fabrikaske avlyina.<br />

Sas khote aba sar dujshela roma, kothe krujal.<br />

Sa kothe ingerde le romen. Tala jekh sino<br />

shudesarde amen, sar le bakren pe jekhavreste.<br />

Angla mende bibolde sasle butaji. Nas avri<br />

uzhardo, le suluma nas avri parude. Na zhangle<br />

pa pende te thoven, haj sa zhuvajle. Kattyi zhuva<br />

kherdyilas khote! Muri chori dej kidas kethane<br />

suluma, colo shudas tele pel suluma te shaj<br />

beshen tele le shavora. Kaver dyes pala miz meri<br />

pale ando vagono shude amen. Sho vardesh<br />

manushen andek vagono. Baro, lungo sas o<br />

zibano. Jekh kurko gelam khatar o Zala eger -<br />

szego zhikaj e Komároma.<br />

Kana tordyilas o zibano, le mursha tele xu -<br />

lyinde pala vagoni, te anen palyi varekatar. Kas -<br />

ke jutisardas, kaske na, kodo trushales ashilas.<br />

Kana kothe samas, kasave samas,sar kon ando<br />

trajo chi diklas paji.<br />

Ande Pápa kode pendas mure dadeske o<br />

shingalo: Rudi, te si tumende love, zha avri an -<br />

do foro, haj kin xaben le shavorenge, dikhav, ke<br />

zurales bokhale. Pinzhardo sas o shingalo,<br />

Söjtöri, zurales lasho shingalo sas, le romenca<br />

kethane. Mure dades zurales kamlas. Nasules<br />

samas ande box. Avri gelas muro dad ando them<br />

mure phralesa haj andas xamasko. Kode phendas<br />

muri dej mure dadeske: na zhal tusa o shingalo,<br />

hirtelen tudott: takarókat meg ruhá kat.<br />

Felsorakoztattak. Levittek úgy másfél kilométerre,<br />

Bakra, mind a tizenhat családot, vagy<br />

százhúsz embert. Nem hagytak egyetlen em -<br />

bert sem.<br />

Bakon a bíró udvarán ültünk a zuhogó esô -<br />

ben, egészen délután háromig, aztán elindultunk.<br />

Zalaegerszegig gyalogoltunk, ott beraktak<br />

a téglagyár udvarába. Volt ott már addigra<br />

vagy kétszáz cigány, a környékrôl mind oda -<br />

gyûjtötték a cigányokat. Egy szín alá bepate rol -<br />

tak bennünket, mint a birkákat az istállóba.<br />

Elôtte zsidók voltak ott sokáig. Nem volt<br />

kitakarítva, a szalma nem lett kicserélve. Tisz -<br />

tálkodni ugye szegények nem tudtak, eltet ve -<br />

sedtek. Annyi tetû megtermett ott, hogy szabályosan<br />

suhogott. Szegény anyám húzott össze<br />

szal mát, ráterítette a lepedôt, hogy a gyerekek<br />

leülhessenek. Másnap délután megint teher va -<br />

gonokba raktak. Hatvan embert egy vagonba.<br />

Nyolc mozdony húzta a vonatot, olyan hosszú<br />

szerelvény volt. Egy hétig mentünk Zala eger -<br />

szegtôl Komáromig.<br />

Ha megállt a vonat, a férfiak leszálltak a va -<br />

gonról, hogy a közelbôl valahonnan hozzanak<br />

vizet. Akinek jutott, jutott, akinek nem, az<br />

szom jan maradt. Mire felértünk, már olya nok<br />

voltunk, mint aki vizet az életben nem látott.<br />

Pápán azt mondja édesapámnak a csendôr:<br />

Rudi, ha van pénz nálatok, menj ki a városba,<br />

vegyél valamit a gyerekeknek, látom, már na -<br />

gyon oda vannak. Ismerôs volt a csendôr, söj töri<br />

volt. Nagyon jó csendôr volt, már a cigá nyokkal<br />

kapcsolatosan. Apámat nagyon szeret te.<br />

Rosszul voltunk az éhségtôl. Kiment apám a<br />

er she was crying when she put our belongings<br />

– everything that she could find quickly: blankets<br />

and clothes – into the bundle. They lined us<br />

up. They took us about one and a half kilometres<br />

away to Bakk, all the sixteen families, some<br />

one hundred and twenty people. They did not<br />

leave anybody behind.<br />

At Bakk, we sat at the judge’s courtyard in<br />

the pouring rain until three o’clock in the afternoon<br />

and then we departed. We walked<br />

to Zalaegerszeg where they put us in the courtyard<br />

of the brickwork. By that time there were<br />

at least 200 Roma. From the neighborhood<br />

they collected the Roma there. They drove us<br />

into the shed as if we were sheep.<br />

Before us, Jews had stayed there for a long<br />

time. The place had not been cleaned, the straw<br />

had not been changed. Those poor Jews, they<br />

could not wash, so they had become infested<br />

with lice and the straw literally swished because<br />

of them. My poor mother made a small strawstack,<br />

put a sheet above it so the children could<br />

sit down. Next afternoon they put us into<br />

freight wagons. Sixty people were in one<br />

wagon. The train was so long that it needed<br />

eight engines to pull the weight. It travelled for<br />

one week from Zalaegerszeg to Komárom.<br />

When the train stopped, the men got off the<br />

wagon to bring water from somewhere. Those<br />

who were lucky got some, the others remained<br />

thirsty. By the time we arrived, we felt like we<br />

had not seen water in our entire lives.<br />

At Pápa a gendarme said to my father:<br />

‘Rudi, if you have money go into town and buy<br />

something for the children, because they are<br />

15

na shadyu le shavoresa. Me ame te meresa, tu<br />

barem le shavoresa ashadyu. Kode phendas<br />

muro dad: so gindyis tume, te merna mange<br />

sostar muro trajo! Amenca ashadyilas.<br />

(…)<br />

Ande Komaroma perdeline amen le granyicengo<br />

shingale. Shipka sas len, haj lungo por pasha<br />

e shipka. Bari rovlyasa marde amen. Ande punre<br />

trubulas te zhas, duj kilometeri zhikaj o<br />

bunkeri. Devlale, so sa khote! Desh bunkeri, sar<br />

ek bari gropa. Savore zhenen kothe ingerde, kattyi<br />

zhene samas, inke vi avri ashadyinen. Sa<br />

katharutne ingerde kothe romen: rumungrora,<br />

beashura, drizanura. Sakofelo romen.<br />

Ratyako avile le sulicishti, avri kide le murshen.<br />

Deshushtare bershendar zhikaj le efta-ok -<br />

to vardesh bershengone manushen. Ingerde le.<br />

Najisinde amendar chorre, kode phendas muro<br />

chorro dad mure dake: amen ingren, na zhanas<br />

kaj, le sama pel shavorra! Avri ingerde les ando<br />

nyamcicko them, panzhvardesh bershenca maj<br />

palal zhanglem, so kherdyilas lesa.<br />

Kaver dyes avile, avri kide le ternye zhulyen,<br />

kas nas shavorra. Muri pheny, e Aranka deshokto<br />

bershengi sas. Opre las mura cinya phenya,<br />

haj mure cine phrales, kade sar te lake savorra<br />

avnas. Chi na phende lake khanchi. Le maj<br />

buten avri ingerde ando nyamcicko them, butyi<br />

te kheren. Amen pale kothe kamne te mudaren.<br />

(…)<br />

Duj kurke pashjilam ando paji, haj ande chik.<br />

Amaro xaben kode sas, tato pajesa tele shorde le<br />

shaha, haj kode phende: xan, tume bale! Pala<br />

thojimo chi ande lindri na tromardam te gin -<br />

dyinas, ej WC kothe sas kaj pamende avilas.<br />

16<br />

városba, a bátyámmal, Gyulával, hozott enni -<br />

valót. Azt mondja neki anyám: te, nem megy<br />

veled csendôr, szökjél meg a gyerekkel. Ha mi<br />

meg is halunk, legalább te maradjál meg a gye -<br />

rekkel. Azt válaszolta apám: mit gondolsz, ha ti<br />

meghaltok, nekem minek az életem! Velünk<br />

maradt.<br />

(…)<br />

Odaértünk Komáromba, átvettek bennünket<br />

a határcsendôrök, vagy kik voltak. Sapkájuk<br />

volt, meg egy pár szál toll volt a sapkájuk után.<br />

Egy kétméteres bottal tereltek, ütöttek, mint a<br />

ré pát. Gyalog kellett menni vagy két kilométert<br />

a bunkerokhoz. Istenem, mi volt ott! Tíz bun -<br />

ker, mint egy nagy gödör. Mindenkit odavittek,<br />

annyian voltunk, hogy még kint az ud va ron is<br />

maradtak. Mindenhonnan szállították oda a<br />

cigányokat: romungrókat, beást, drizárt.<br />

Mindenféle cigányt, ami létezik.<br />

Este jöttek a nyilasok, kiszedték a férfiakat.<br />

Tizennégy évtôl egész hetven-nyolcvan éves<br />

korig. Elvitték ôket. Elbúcsúztak szegények, azt<br />

mondta szegény apám anyámnak: minket<br />

elvisznek, nem tudjuk hová, vigyázz a gye re -<br />

kekre! Kivitték Németországba, ötven évvel<br />

késôbb tudtuk meg, mi történt vele.<br />

Másnap jöttek, kiválogatták a fiatal nôket,<br />

akinek nem volt családja. A nôvérem, Aranka<br />

tizennyolc éves volt. Felvette az egyik húgomat<br />

meg az öcsémet, mintha az ô gyerekei len né -<br />

nek. Nem is szóltak neki semmit. A többieket<br />

kivitték Németországba dolgozni. Min ket meg<br />

ott akartak elpusztítani.<br />

(…)<br />

Két hétig szenvedtünk, sárba, vízbe feküdtünk.<br />

getting ill.’ I knew the gendarme. He was from<br />

Söjtör. He was a very good gendarme, at least<br />

with the Roma. He liked my father a lot. We<br />

were ill from hunger. My father went into the<br />

town with my brother Gyula and brought food.<br />

My mother told him: ‘Hey, the gendarme will<br />

not go with you, run away with the child! Then<br />

if we die, at least you and the child will survive.’<br />

My father replied: ‘What are you thinking? If<br />

you die, I don’t want to live!’ He stayed with us.<br />

(…)<br />

We arrived in Komárom and were taken over by<br />

the border gendarmes, or whatever they were.<br />

They wore caps and on them there were a couple<br />

of feathers. They herded us with a two meter<br />

long stick and they hit us whenever they could.<br />

We had to walk one or two kilometres to the<br />

bunkers. Oh my god, it was hell! Ten bunkers<br />

like a big hole. They took everybody there. We<br />

were so many, that many had to stay out in the<br />

courtyard. All Gypsies were taken there: the<br />

Romungre, the Beash, the Drizars. All kinds of<br />

Gypsies.<br />

In the evening the Arrow Cross men came.<br />

They sorted out the men. From fourteen to seventy-eighty<br />

years old. They were taken away.<br />

The poor said goodbye. My poor father said to<br />

my mother: ‘They will take us, we don’t know<br />

where, take care of the children!’ They took him<br />

to Germany, and we only found out 50 years<br />

later what happened to him.<br />

Next day they came and took those young<br />

women who did not have families. My sister<br />

Aranka was 18 years old. She picked up one of<br />

my little sisters and my little brother as if they

Detehara vurdonesa kide kethane le mulen. Sar<br />

pek farmo, kana murdajven le bale: opre suden<br />

le po vurdon, pala kode andre dugoske xajing.<br />

Kherde ek bari gropa, kothe shudinele, pala<br />

kode mesosa shordele tele.<br />

(…)<br />

Pala kode avile le bombicke reploplanura, kade<br />

pashal avile kaj o bunkeri, zhikaj phuv tele<br />

bombazisarde o objektumo. Amerikana, anglika,<br />

me na zhanav so sas le. Dikhle le rome sar<br />

daran. Avilas jekh reploplano, kade tele huri -<br />

sardas, lake phaka tele resne pe phuv, hurane<br />

papirura rispisardas. Pasha muri dej tordyindom,<br />

avri nashlom opre lom jekh, andre ingerdom<br />

les. Kode sas pe leste skirime, na daran<br />

mure kamade ungrika phrala, na butajig avna<br />

khate. Kaver dyes dore o Hitler xutyeldas jek<br />

telegrammo, te na ingrena avri le romen, an daro<br />

komáromesko bunkeri, zhikaj ej phuv tele<br />

marna intrego nyamcicko them.<br />

Inke te ashadyuvas duj dyes, muri pheny aba<br />

chi avel khere. Sar o kokalo sas chorri. Pe ra tyate<br />

apoj avile le nyamcicka ketane, dine amen ge<br />

fusuj, haj kode phende: sako kidelpe khetane, haj<br />

shaj zhal. Akanak kaj shaj zhas, kana ratyi si?<br />

Sakon xutyildas peske shavores thaj gelastar.<br />

Chi zhanav apoj, zhi kaj reslas kodo, kaske<br />

inke sas papuchi? Na gelem numa panzh<br />

meteri, kasavi chik sas amari papuchi tele las pe<br />

punre.<br />

Gelem zhi kaj er Komárom, kothe andre<br />

gelem kaj tordyol o zibano, le shingale avri<br />

nash adinde amen, ke le zhuva pernas anda<br />

mende. Vash le zhuva nashtig gelem pe zibano,<br />

pe punre gelam maj dur, zhi kaj Ács. Kothe o<br />

Az ennivalónk az volt, hogy leforrázták a fejes<br />

káposztát, hintettek rá egy kis köménymagot,<br />

és mondták: egyetek disznók! A fürdésrôl ál -<br />

mod ni sem mertünk, a vécé ott volt, ahol épp<br />

rá juk ért. Reggelente lovaskocsival szedte össze<br />

egy ember a hullákat. Mint egy gazdaságban,<br />

mi kor döglenek a disznók: földobálják a kocsi ra,<br />

aztán bele a dögkútba. Ástak egy nagy göd röt,<br />

oda dobták, aztán mésszel leöntötték ôket.<br />

(…)<br />

Aztán jöttek a bombázó repülôk, jó közelre<br />

a bunkerokhoz is, puhára bombázták az állo -<br />

mást. Amerikaiak vagy angolok, mit tudom én.<br />

Látták, hogy a cigányok hogy szenvednek. Jött<br />

a gép, olyan alacsonyan repült, hogy a szár nya<br />

majdnem elérte a földet, röpcédulákat szórt.<br />

Anyám mellett álltam, futás ki, felkaptam<br />

egyet, bevittem. Az volt ráírva, hogy kedves<br />

magyar testvérek, ne féljetek, nem sokáig lesz -<br />

tek itt. Másnap állítólag Hitler kapott egy táviratot,<br />

hogy amennyiben a Komáromi bunke -<br />

rokból nem távoztatja el a cigányokat, porrá<br />

verik egész Németországot.<br />

Ha még maradunk két napot, a nôvérem<br />

már nem jön haza. Csontváz volt szegény. De<br />

egy este aztán jöttek a német katonatisztek,<br />

bab fôzeléket adtak, és mondták: mindenki pa -<br />

kol jon és mehet. De hová tudjunk menni éj sza -<br />

ka idején?<br />

Mindenki fogta a gyerekét, elindultunk.<br />

Hogy meddig ment cipôvel az, akinek még volt<br />

egyáltalán? Úgy öt métert, mert a sár levet te.<br />

Térdig érô sár volt.<br />

Komáromig elgyalogoltunk, ott bementünk<br />

a váróterembe, de a csendôrök kizavartak, mert<br />

were her children. So the Arrow Cross men did<br />

not bother her. They took the others to work in<br />

Germany and they wanted to kill us there.<br />

(…)<br />

We suffered for two weeks. We were lying in<br />

mud and water. The only food they gave us was<br />

a cabbage, which they poured boiling water on<br />

and sprinkled it with a little caraway seed. And<br />

they said: ‘Eat pigs!’ Bathing was out of the<br />

question and we went to the toilet wherever we<br />

had to. In the morning, a man came and collected<br />

the dead with a horse-drawn cart. It was<br />

like on a farm, when the pigs died: they put<br />

them on the cart and then threw them into the<br />

carcass-well. They dug a big hole, they threw<br />

them in and spilled lime on them.<br />

(…)<br />

Then the bombers came, they dropped their<br />

bombs close to the bunkers, they bombed the<br />

station. They were American or English, I don’t<br />

know. They saw how Roma were suffer ing. The<br />

plane came, it flew so close that its wings<br />

almost touched the ground. It distributed<br />

leaflets. I was standing next to my mother. Then<br />

I ran out and picked one up. It said: ‘Dear<br />

Hungarian friends, don’t be scared, you won’t<br />

be here for long!’– was written on it. The next<br />

day Hitler, allegedly, received a telegram saying<br />

that if he did not let the Roma leave the<br />

bunkers at Komárom, Germany would be<br />

destroyed.<br />

If we had stayed another two days, my sister<br />

wouldn’t have made it. She was like a skeleton.<br />

But one evening German officers came, gave us<br />

beans, and said we could pack and that we were<br />

17

zibanesko shero kodo phendas: „Romnye na<br />

zhan maj dur, ke keras jek vagono inke thaj<br />

khere shaj zhan”. Le familijako love mande sas,<br />

ande dikhlesko agor sudas andre muri dej. Chi<br />

ratyi, chi dyesesa na lom tele kado dikhlo. Mu -<br />

ri dej avri las e love thaj gelas te kinel amenge<br />

variso xaben, ame kothe asilem ando zibanesko<br />

kher. Kanak palpale avilas muri dej aba chi<br />

rakh las amen, ke atunchi aba opre gelem ando<br />

vagono. Chingardem lake: kathe sam!<br />

Gelemtar zhi kaj e Pápa kothe pale malavenas<br />

le bombenca. Na resel ande muro shero<br />

kat har zhangle e reploplanura, ande zibano ro -<br />

ma si? Kodo zibano chi azbade.<br />

(…)<br />

Ande Pápa po vagono mulas muri lala, lake duj<br />

shavora, jekh shej thaj jekh shavo. O jekh, jekh<br />

ber shengo sas o kaver duj. Tifuszosha kerdyile.<br />

Le ungrike kethane shunde ke rovas thaj kothe<br />

avile. Avri line len andar o vagono. Kaj prahosarde<br />

le duj cine mulen, chi zhanav. Shajke jek<br />

ande jek buzulyi.<br />

Khere reslem ande Zalaegerszega. Ando<br />

ziba nosko kher na mukhas amen andre, avri<br />

gelem pe vulyica, kothe pale avile le nyamcura.<br />

Phenen amenge, kathar tumen na zhan<br />

khanikaj, beshen tele! Akanak so avla amenca,<br />

pale palpale ingren amen?<br />

Kothar kaver trin manusenca nashelastar muri<br />

pheny, e Aranka. Ande Sárhida gele tele. Khere<br />

resle chorre, de pe soste! Pe zidura. Chi jekh<br />

gad, chi jekh roj, chi jekh tigalya, chi vudar, chi<br />

felyastra nas ando kher. Le gaveszko po poularo,<br />

le gazhe avri chorde lendar sakofelo.<br />

Pe ratyate apoj vi amen khere reslam: le<br />

18<br />

a tetû hullott belôlünk. Elindultunk gyalog,<br />

mert vonatra nem szállhattunk föl a tetû miatt.<br />

Ácsig gyalogoltunk, ott aztán újra próbálkoztunk.<br />

Az állomásfônök kijött és mondta: „asz -<br />

szonyok, ne menjenek sehová, kapnak majd egy<br />

vagont, az elviszi magukat haza”. A család<br />

pénze nálam volt, egy kis vállkendôbe varrta<br />

bele anyám. Se éjjel, se nappal le nem vettem.<br />

Anyám kivette a pénzt, elment a faluba enni -<br />

valóért, mi meg ottmaradtunk az állomáson.<br />

Jött vissza anyám, keresett bennünket, de sze -<br />

gény nem látott minket, mert addigra már a<br />

vagonban voltunk. Kiabáltunk neki, hogy itt<br />

vagyunk.<br />

Elindult a vonat, elértünk Pápáig, ott me gint<br />

el kezdték veretni az állomást. Nem fér bele a<br />

fejembe, honnan tudták a repülôk, hogy a<br />

vonatban cigányok vannak? Azt a vonatot nem<br />

bántották.<br />

(…)<br />

Pápán a vagonban meghalt a nagynéném két<br />

gyermeke, egy fiú meg egy lány. Az egyik<br />

egyéves volt, a másik kettô. Tífuszosak lettek.<br />

A magyar katonák átjöttek, meghallották, hogy<br />

sírunk. Kivették ôket a vagonból. Hogy hová<br />

temették el a két kis holttestet, nem tudom.<br />

Eláshatták ôket a bokorban.<br />

Hazaértünk Zalaegerszegre, kiszálltunk a<br />

va gonból. Az állomásra nem engedtek be, az ut -<br />

cára mentünk, de ott megint jöttek a németek.<br />

Innen nem mentek sehová, ide üljetek le! Most<br />

mi lesz velünk, újból visszavisznek? On nan<br />

másik három emberrel együtt meg szökött a<br />

testvérem, Aranka. Gyalog lementek Sárhidára.<br />

Hazaértek, de mire mentek szegények haza!<br />

free to leave. But where could we go at night?<br />

Everybody took their children and left. How<br />

long did the shoes of those who still had them<br />

last? About five meters, and then they lost them<br />

in the mud. The mud reached up to our knees.<br />

We walked to Komárom and went into the<br />

railway station’s waiting-hall. However, the<br />

gendarme sent us out because lice were falling<br />

out of us. We could not get on the train because<br />

of the lice, so we left on foot. We walked to Ács,<br />

where we tried again. The station master said to<br />

us: ‘Women, don’t go anywhere! A wagon will<br />

come soon and it will take you home.’ I had the<br />

family’s money. My mother had sewn it in my<br />

scarf. I would never take it off. My mother took<br />

the money out of it and went into the village<br />

for food, while we were stayed at the station.<br />

When she came back, she was looking for us.<br />

But she could not see us because we were<br />

already in the wagon. We shouted to her.<br />

The train departed and when we arrived at<br />

Pápa, the planes started bombing again. I have<br />

no idea how the pilots knew that there were<br />

Roma in the train. They did not harm that<br />

train.<br />

(…)<br />

At Pápa in the wagon two children of my aunt<br />

died: a boy and a girl. One of them was one year<br />

old the other two. They got typhus. Hungarian<br />

soldiers came over because they heard us crying.<br />

They took them out of the wagon. Where<br />

did they bury them? I don’t know. Probably,<br />

they buried them in a bush.<br />

We arrived in Zalaegerszeg. We got out of<br />

the wagon. We were not allowed to go to the

nyamcura opre shude amen po vagono, kade<br />

ingerde amen khere. Kanak tordyolas o zibano,<br />

chi mukhnas amen avri, numa detehara. Muri<br />

dej chingardas, e Aranka shundas thaj pala<br />

amende avilas, phuterdinde o vagono.<br />

Khere reslam. Kon khere nashilas aba pha -<br />

bardas jag. Po jekh kher inke sas kasht, kodo tele<br />

kide. Kon avri asadyilas, kodolen marelas o<br />

brishind. Kaver dyes opre ushtyile le romnya,<br />

aba ande kaste, sas inke zor, thaj duj kerde<br />

khetane kher. Opre gele ando gav, kathar le<br />

gazhe xutyilde tover, firizo. Tele avilas le ga -<br />

vesko mujalo, thaj avri chingardas: khere avile le<br />

gaveske chorre, kon sar zhanel, te zhutil len.<br />

Kade ande amenge ek cino xaben, colura ande<br />

soste te sovas. Shaj khalem. Kanak chikenalo<br />

xaben sas, le roma sa pashlyonas. Le gavesko<br />

mujalo vi kodo avri chingardas, sako detehara,<br />

sako kher trubul te del panzh litero thud. Me<br />

gelom tele pala thud, duvar trubulas te zhav te<br />

avel sakoneske thud. Pala jek-duj kurke khere<br />

avile duj manusa, kon butyenge ketane sas. An -<br />

do Zalaegerszego ande zhulyenge gada huri -<br />

sarde pen kade zhangle te ashadyon khere.<br />

Kodol apoj shinnas le kasht le romenge te na<br />

pahosajven.<br />

(…)<br />

So le romnye manga kerde, ando gav ame ko do<br />

xalam. Andar o vesh ame andam kasht.<br />

Baro jiv sas, trin khera mardam tele, te shaj<br />

keras jag. Kana avilas o fronto, ando duj khera<br />

samas savorezhene.<br />

Atunchi le rusura pushke dine mura dake<br />

kuj. Sas mashkar amende vi ungrika manusha,<br />

ketana, chorre. Chi nashadam khanikas, loshaj -<br />

A négy falra. Semmi, egy rongy, egy kanál, egy<br />

pohár, egy ajtó, egy ablak nem volt. A falusi nép<br />

kirabolta a házakat.<br />

Aztán estére leértünk mi is: a németek fölraktak<br />

minket egy vagonba, úgy vittek hazáig.<br />

Megállt a vonat, de nem akartak bennünket<br />

kiengedni, majd csak reggel. Anyám kiabált,<br />

meghallották Arankáék, értünk jöttek, kinyitották<br />

a vagont.<br />

Hazaértünk. Akik elszöktek, már tüzeltek.<br />

Az egyik lakáson még rajta volt a fele tetô,<br />

azt szedték le. Akik kint rekedtek, verte ôket az<br />

esô. Másnap reggel fölkeltek az asszonyok, már<br />

akibe még volt annyi erô, megcsináltak két<br />

házat. Fölmentek a faluba és kaptak a parasztoktól<br />

fejszét meg fûrészt. Lejött a falusi bíró,<br />

kidoboltatta a faluban: hazajöttek a falu sze gé -<br />

nyei, ki hogyan tudja, segítse ôket. Így hoztak le<br />

egy kis ennivalót, takarót. Ehettünk. Amikor<br />

zsírosat ettek, az egész telep mind feküdt. Meg<br />

kidoboltatta a bíró, hogy minden reggel minden<br />

ház öt liter tejet adjon. Én mentem le a tejért,<br />

kétszer fordultam, mire kihordtam a tejet a<br />

cigányokhoz. Egy-két hét után aztán hazajött<br />

két férfi a munkaszolgálatos katonaságtól.<br />

Zalaegerszegen voltak, átöltöztek nôi ruhába,<br />

úgy tudtak megmaradni. Azok aztán vágták<br />

a fát mindenkinek, hogy ne fagyjanak meg.<br />

(…)<br />

Amit koldultak az asszonyok, abból éltünk.<br />

Mentünk kéregetni, az erdôbôl hoztuk a fát.<br />

Nagy hó volt, három házat lebontottunk, hogy<br />

tüzelni tudjunk. Mikor jött a front, két lakásba<br />

húzódtunk mindannyian.<br />

Akkor az oroszok meglôtték anyám karját.<br />

station, so we went to the streets, but there the<br />

Germans came again. ‘You don’t go anywhere,<br />

sit down!’ What will happen to us? Would they<br />

take us back? My sister Aranka and three other<br />

people escaped from there. The walked to Sár -<br />

hida. They arrived home, but for what! They<br />

only saw the four walls. There was nothing, not<br />

even a spoon, a glass, a door, a window, nothing.<br />

The village people had robbed the houses.<br />

By evening, we had arrived as well. The<br />

Germans put us on a wagon and escorted us<br />

home. The train stopped, but they did not want<br />

to let us out until morning. My mother was<br />

shouting, Aranka and the others heard it, so they<br />

came and opened the wagon.<br />

We arrived home. Those who had escaped<br />

were already burning wood. One of the flats had<br />

half of its roof, they tore that down. Those who<br />

could not get in, were hit by the rain. The next<br />

morning the women got up and those who still<br />

had some strength mended two houses. They<br />

went to the village got axes and saws from the<br />

peasants. The village judge came down and had<br />

it announced by the sound of the drum that the<br />

poor of the village had arrived and everybody<br />

should help them as they could. So they<br />

brought us some food and blanket. We could<br />

eat. When they had greasy food, everybody was<br />

lying in the settlement. Then the judge had it<br />

announced that every house should give five<br />

litres of milk in the morning. I was the one who<br />

went to fetch the milk. It had gone there two<br />

times before I could get the milk to the Roma.<br />

One or two weeks later two men arrived from<br />

forced labour service. They had been at<br />

19

lam te maj but zhene samas. Mashkar o plajo<br />

dikhle, varikon kothe cirdelpes, nyamcenge<br />

dikhne len, thaj puske dine pe ame. Pe duj thanende<br />

pushkinde mure dake kuj, muri pheny pe<br />

laki kuj sas, le kaver kujasa kamlas la te sha ravel.<br />

Chi akanak chi zhanav opre te gindyi sar maladyilas<br />

ke la cinyi shake khanchi bajo na maladyilas.<br />

Pala kede avile le rusura. Sas mash kar<br />

amende jekh romnyi haj phendas: dikhen! Man<br />

naj chi cino, chi baro, korkori som. Vi pushke te<br />

den man chi mukhav, khanyikas pala mande.<br />

Xutyeldas ek parno colo, avri shudas les pe jekh<br />

kasht, pe le kheresko agor. Chi pushkisarde maj<br />

dur pa maro kher, pala kede avile le rusura.<br />

Phenel e romanyi romnyi: te dik has ke aven le<br />

rusura, ashas avri haj maras kethane amare vas<br />

lenge. Vi kade sas. Chi na azbade amen, andre<br />

phangle muri dake kuj.<br />

Anda chik opre cirdam jekh kher, pala kode<br />

zhuvindam sar zhanglam. Kaj le gazhe phirdam<br />

butyi te keras. Kasavi dej nas sar muri dej sas.<br />

Tranda thaj panzhe bershengi sas, kana korkori<br />

ashilas, haj chi gelas romeste. Opre barardas<br />

amen bi dadesko.<br />

(…)<br />

Kon maj sigo manglas ma karing leste gelom.<br />

Deshushovengi bershengi somas. Türjevicko sas,<br />

duj bersh beshlam khetane kaj muri sokra.<br />

Lestar rakhadyilas muro baro shavo. Numa lila<br />

shudelas, thaj pelas, so me rodos, vi kodo sa<br />

pelas. Phendom leske, dikh! Te na avesa maj<br />

lasho, kathe mukhav tut, zhavtar le shavoresa. Vi<br />

leski dej kasavi sas, ke zhanglom te dav, lashi<br />

somas, te na atunchi sa kethane marde ma.<br />

Gindyisardom, kado naj trajo. Chi kamlom ka -<br />

20<br />

Voltak közöttünk magyar emberek, katonák,<br />

menekültek szegények. Nem zavartunk el sen -<br />

kit, örültünk, ha többen voltunk. A hegyoldalból<br />

meglátták, hogy ott valaki bujdosik, németeknek<br />

hitték ôket, elkezdtek ránk lövöldözni.<br />

Két helyen átlôtték anyám karját. A húgom épp<br />

a karján volt, hogy megvédje, a másik karjával<br />

próbálta eltakarni ôt. A mai napig sem tudom<br />

felfogni, hogyan történhetett, a kislánynak sem -<br />

mi baja sem lett. Aztán jöttek az oroszok. Volt<br />

egy asszony közöttünk az mondta: nézzétek!<br />

Nekem nincs se kicsim, se nagyom, egyedül<br />

vagyok. Ha meg is lônek nincs baj, nem hagyok<br />

magam után gyereket. Megfogott egy fehér<br />

lepedôt, kitette egy fára a ház sarkára. Mindjárt<br />

megszûnt a lövöldözés, aztán jöttek<br />

az oroszok. A cigány asszony azt mondja: ha<br />

látjuk, hogy jönnek az oroszok, álljunk ki és tapsoljunk<br />

nekik. Úgy is volt. Nem is bántottak<br />

senkit sem, ellátták anyám sebét.<br />

Sárfalból felhúztunk egy lakást, aztán éltünk,<br />

ahogy tudtunk, a koldusságból. Napszámba jártunk.<br />

Olyan anya nem volt, mint az én anyám.<br />

Harmincöt évesen maradt özvegy, de férjhez<br />

nem ment. Felnevelt bennünket apa nélkül.<br />

(…)<br />

Az elsô kérôhöz hozzámentem. Tizenhat éves<br />

voltam. Türjei volt, két évig éltünk ott együtt az<br />

anyósomnál. Tôle született az idôsebbik fiam.<br />

De csak kártyázott, ivott, amit én keres tem, azt<br />

is elszórta. Mondtam neki, nézd, vagy megjavulsz,<br />

engem meg a gyereket választod, vagy<br />

elválunk. Az anyja is olyan volt, hogy ha tudtam<br />

adni, jó voltam, ha nem tudtam adni, nem<br />

voltam jó. Ütve-vágva voltam. Na, gondoltam,<br />

Zalaegerszeg, they had changed to women’s<br />

clothes in order to survive. They had chopped<br />

wood for everybody, so nobody had frozen.<br />

(…)<br />

We lived on the money that the women<br />

begged. We went out to beg and brought firewood<br />

from the woods. Huge snow covered the<br />

ground and we had to tear down three houses<br />

for heat. When the front came all of us squeezed<br />

into the two flats.<br />

Then the Russians shot my mother’s arm.<br />

There were Hungarians, soldiers, refugees<br />

among us. We did not send away anybody: the<br />

more, the merrier. When they saw from the hills<br />

that people were hiding down there, they<br />

thought we were Germans and they started<br />

shooting at us. They shot through my mothers<br />

arm at two places. My little sister was on her<br />

other arm and she covered her with this arm to<br />

protect her. To this day I cannot understand how<br />

that little girl survived without a scar. Then the<br />

Russians came. There was a woman among us<br />

who said: ‘Look! I don’t have child ren, I’m<br />

alone. If they shoot me, I won’t leave anybody as<br />

an orphan behind.’ So she took a white sheet,<br />

put it on a wood in the corner of the house. The<br />

shooting stopped immediately and then the<br />

Russian came. A Romani woman said that<br />

when we see the Russians coming, we should<br />

step outside and applaud them. That was what<br />

we did. They did not hurt us and they looked<br />

after my mother’s wounds.<br />

We made a house out of mud and we lived<br />

as we could by begging. We worked by the day.<br />

There was no mother like mine. She had

ver romes te pinzharav, de romeste gelom.<br />

Khere gelom kaj muri dej pe Sárhida. Trin-shtar<br />

bersh barardom korkori muri shaves. Pala kode<br />

pale romeste gelem: ando Bükkösdo pek milajeski<br />

butyi pinzhardom les, me somas bish thaj<br />

jekh, voj sas bish thaj shove bershengo. Atunchi<br />

aba me na gelem khere. Najis loe Dev leske vi<br />

adyes kethane sam le. Chorro zu rales nasvaloj.<br />

Mure romeske kathar jek kaver romnyi sas<br />

jek duje bershengo shavo, kas voj barardas.<br />

Phen dom leske: kade zhav tute, me na beshav<br />

ande jek kher la sokrasa. Ke dosta sas aba anda<br />

jek sokra. Kode phendas, chi na kamav tut kothe<br />

te ingrav, si ma rigate kher. Na, kade mishtoj.<br />

Kethane ashadyilam, so le duj shavora manca<br />

avile. Ande Bükkösd po romano than sas amen<br />

jek cino kher. Muro rom sa butyi kerlas, sas kana<br />

numa pala jek kurko dikhlom les, ke ando Pécs<br />

beshlas, butyano zhutori sas. Me pale kaj le<br />

gazhe phirdem sako dyes, butyi te kerav, muri<br />

sokra las sama pe shavora. Le shavora pale avile<br />

pala jekhkhaver. Kathar kado rom rakhadyilas<br />

man shov shavora, kathar o kaver sas ma jek,<br />

mure romes kathar e anglu nyi romnyi sas les<br />

jek, vi kada les me barardom. Vi kade dikhav les,<br />

sar te me andomas les pe luma.<br />

Kana rakhadyile le anglune duj shavora, avri<br />

avilas e baba thaj kode phendas: Frida! Chi<br />

kames kothe te des le jek shavores varikaske?<br />

Phendom lake, pusztin tut kathar! O svunto<br />

Del phendom te bakres das vi mal dela pasa<br />

lende. Te pe luma te andom len, atunchi vi opre<br />

bararav len, vi te chorri avo.<br />

Pala kede opre avilam ando Csór. Muro rom<br />

atunchi ando Inota ando marhime vigna kerlas<br />

ez nem élet. Hiába nem akarom, hogy máshoz<br />

menjek, mást ismerjek, de muszáj volt, hazamentem<br />

anyámhoz Sárhidára. Három-négy<br />

évig neveltem egyedül a fiamat. Aztán me gint<br />

férjhez mentem: Bükkösdön egy idénymunkán<br />

ismerkedtem meg vele, én 21 éves voltam, ô 26.<br />

És akkor ugye én már nem men tem haza. Hála<br />

Istennek, máig együtt vagyunk. Szegény nagyon<br />

beteg.<br />

A férjemnek egy másik asszonytól volt egy<br />

kétéves fia, akit ô nevelt. Megmondtam neki:<br />

úgy megyek hozzád, hogy én anyóssal egy pillanatig<br />

nem maradok egy lakásban. Mert az<br />

anyósból már ölég volt. Azt mondja, nem is<br />

akar lak odavinni, nekem külön van lakásom.<br />

Mondom, semmi kifogásom. Összekerültünk,<br />

mind a két gyerek hozzám került. Bükkösdön, a<br />

cigánytelepen volt egy szoba-konyhánk.<br />

A fér jem állandóan dolgozott, volt, hogy csak<br />

hétvégén láttam, mert szállón lakott Pécsett, ott<br />

volt segédmunkás. Én meg eljártam napszámba,<br />

az anyósom elvállalta a gyerekeket napközben.<br />

A gyerekek meg jöttek sorban. Ettôl a<br />

férjem tôl hat gyereket, a másiktól egyet, meg a<br />

férjem elôzô házasságából származó gyermekét<br />

is én neveltem fel. Azt is úgy nézem, mintha én<br />

hoztam volna a világra.<br />

Amikor megszülettek az elsô ikreim, kijött<br />

a bába, és azt mondta: Fridám, nem adol egyet<br />

az intézetbe? Mondtam neki, takarodjál ki in -<br />

nen! Ha az Isten, mondom, bárányt adott, majd<br />

legelôt is ad neki. Ha világra hoztam, akkor föl<br />

is nevelem, akármilyen szegénységben.<br />

Aztán hatvanban feljöttünk Fejér megyébe,<br />

Csórra. A férjem akkor már az inotai alumíni-<br />

become a widow at the age of thirty-five, but<br />

she had never married again. She raised us all by<br />

herself, without a father.<br />

(…)<br />

I married my first suitor. I was sixteen. He was<br />

from Türje, where we lived for two years at my<br />

mother-in-law’s. My older son is his. But he<br />

played cards all the time, drank and wasted even<br />

the money I had earned. I told him: ‘Look! You<br />

either get better and choose me and the kid or<br />

we will divorce.’ His mother was the same.<br />

When I brought them money I was good, when<br />

I could not give then I was not good. They hit<br />

me all the time. So, I thought this was not life.<br />

I did not want to get know nor marry anybody<br />

else, but I had to go home to my mother to<br />

Sárhida. For three or four years I raised my son<br />

alone, then I remarried. I met him on a seasonal<br />

work at Bükkösd. I was 21, he was 26. And<br />

then I did not go home. Thank God, we are still<br />

together. He is very ill.<br />

My husband had a two-year-old son from<br />

another woman, whom he raised alone. I told<br />

him that I would only marry him if I did not<br />

have to live with my mother-in-law. He said he<br />

did not want to take me there, and that he had<br />

a flat. I said I did not mind. We got together, so<br />

I had two children. In Bükkösd, at the Romani<br />

settlement, we had a one-room flat. My husband<br />

worked all the time. I only saw him on<br />

weekends, because he lived in a worker’s hostel<br />

at Pécs, where he worked. I worked by day and<br />

my mother-in-law took care of the children<br />

during the day. And the children came one after<br />

the other. I raised all the six children from this<br />

21

22<br />

umkohónál dolgozott, mint kohász. Kitanulta a<br />

kohászszakmát. Ott is ment tönkre. Ott meg -<br />

kapta a szív- és tüdôasztmát. Leszámoltatták és<br />

áttették tüskehúzónak. Sokszor úgy jött haza,<br />

hogy a ruha végig ki volt rajta égve. Kezdett baj<br />

lenni az egészségével. Volt ugyan orvo sok nál, de<br />

azt mondták, hogy nem akar dolgozni, azért<br />

csinálja. Le lehetett volna százalékoltatni, de<br />

nem akarta. Aztán Pétre ment, a bányába széntermelôként<br />

dolgozott három évig. Volt egy<br />

bányaszakadás, amit két ember úgy élt át, hogy<br />

két nap, két éjjel a szén alatt voltak, de a másik<br />

három meghalt. Ezután leszámoltattam a mun -<br />

kahelyérôl. Évente háromszor-négyszer a kór -<br />

há zi ágyat nyomja. Hetvenhárom éves, har minc<br />

év munkaviszonnyal a háta mögött har minc -<br />

háromezer forint rokkantnyugdíjat kap.<br />

(…)<br />

Nem tudtam otthon maradni egy percig sem.<br />

Elôször gyalog vagy busszal, vonattal, utána<br />

meg lovas kocsival jártam a környékbeli falvakat<br />

és tanyákat. Jósoltam is. Aztán jártam tollazni,<br />

rongyozni Inotára, Sárkeszire, Sárszent mi -<br />

hályra, még messzebbre. A parasztok sose za -<br />

vartak el, tudták, hogy nem lopok. Volt, hogy<br />