Sierra Samaritans - National Ski Patrol

Sierra Samaritans - National Ski Patrol

Sierra Samaritans - National Ski Patrol

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

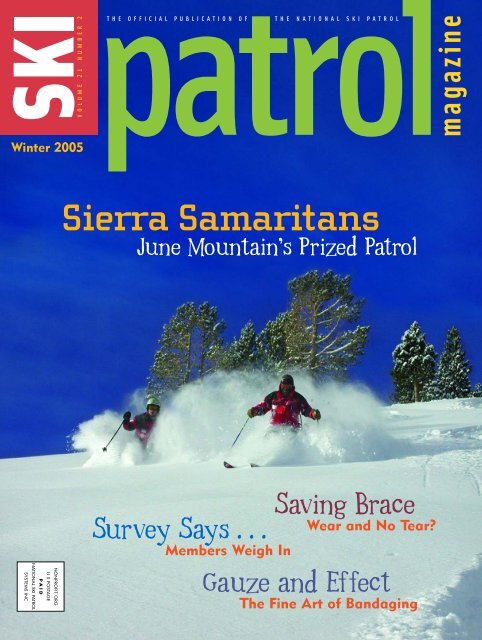

V O L U M E 2 1 N U M B E R 2<br />

T H E O F F I C I A L P U B L I C A T I O N O F<br />

T H E N A T I O N A L S K I P A T R O L<br />

Winter 2005<br />

<strong>Sierra</strong> <strong>Samaritans</strong><br />

June Mountain , s Prized <strong>Patrol</strong><br />

Saving Brace<br />

Survey Says . . .<br />

Wear and No Tear?<br />

Members Weigh In<br />

SYSTEMS INC<br />

NATIONAL SKI PATROL<br />

P AID<br />

U S POSTAGE<br />

NONPROFIT ORG<br />

Gauze and Effect<br />

The Fine Art of Bandaging

<strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine❚ Winter 2005<br />

8<br />

June Mountain <strong>Patrol</strong><br />

A Quality Crew in the <strong>Sierra</strong>s<br />

Down the road from its Mammoth neighbor, a small hill<br />

and the patrollers who call it home earn big kudos.<br />

❚ By Ingrid Tistaert<br />

16<br />

24<br />

Brace Yourself<br />

Knee Injuries May Be Preventable<br />

Take it from one who knows; experience shows. After two ACL<br />

tears and two surgeries, one man put away the ego and put the<br />

knee brace back on. ❚ By Michael Patmas, M.D.<br />

Nutrition on the Slopes<br />

Solutions for the Fast Food Blues<br />

You’re not really gonna eat that, are you? Use our quick and<br />

easy guide to the do’s and don’ts of on-mountain munching.<br />

❚ By Robin Peglow<br />

contents<br />

features outdoor<br />

8all together now<br />

we can rebuild him<br />

16<br />

balancing act<br />

30<br />

30<br />

36<br />

40<br />

ARTICLES<br />

On Solid Ground: One Hour to Enhanced Balance<br />

❚ BY LLOYD MULLER AND JILL WILLIAMSON<br />

Autism Awareness: A <strong>Patrol</strong>ler’s Guide<br />

❚ BY SCOTT CAMPBELL<br />

Surveying the Scene: Members Offer Association Insight<br />

❚ BY MARK DORSEY<br />

Blue skies and powder abound<br />

as June Mountain patrollers<br />

Kirk Maes (left) and Chris Lizza<br />

take some turns in the high<br />

<strong>Sierra</strong>s. Photo by Eric Diem.<br />

COVER<br />

44<br />

4<br />

54<br />

6<br />

60<br />

62<br />

74<br />

76<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Avalanche & Mountaineering<br />

❚ Zoning in on New Probing Tactics<br />

❚ Be Slide-Wise to Navigate Direct Route to Avvy Info<br />

Commentary<br />

❚ Upping the Quality Quotient<br />

In Memoriam<br />

Letters<br />

News Briefs<br />

Outdoor Emergency Care<br />

❚ That’s a Wrap: Wound Bandaging Made Easy<br />

Index<br />

Out of Bounds

NSP VISION: NSP’s vision is to be the premier provider<br />

of outstanding education programs and services benefiting<br />

the global outdoor recreation community.<br />

EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT<br />

Rebecca W. Ayers, Editor<br />

Wendy Schrupp, Associate Editor<br />

Jim Schnebly, Assistant Editor<br />

Deborah Marks, Assistant Editor<br />

AD SALES/SPONSORSHIP INQUIRIES<br />

Mark Dorsey, Marketing Director<br />

133 S. Van Gordon St., Suite 100<br />

Lakewood, CO 80228-1700<br />

(303) 988-1111<br />

Fax: (800) 222-I-SKI (4754)<br />

E-mail: marketing@nsp.org<br />

DESIGN & PRODUCTION<br />

EnZed Design<br />

SKI PATROL MAGAZINE<br />

is an official publication of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> System,<br />

Inc., and is published four times per year.<br />

ISSN 0890-6076<br />

©2005 by the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> System, Inc. No part of<br />

this publication may be reproduced by any mechanical,<br />

photographic, or electronic process without the express<br />

written permission of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> System, Inc.<br />

Opinions presented in <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine are those of the<br />

individual authors and do not necessarily represent the<br />

opinions or policies of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> System, Inc.<br />

CHANGE OF ADDRESS<br />

Address changes and inquiries regarding subscriptions<br />

should be sent to <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine, 133 S. Van Gordon<br />

St., Suite 100, Lakewood, CO 80228-1700. Address changes<br />

must include the NSP membership I.D. number, and it is<br />

helpful to reference the old address and ZIP code as well as<br />

the new. Association members can also indicate a change<br />

of address online through the member services site at<br />

www.nsp.org. The post office will not forward copies to<br />

you unless you provide additional postage. Replacement<br />

copies cannot be guaranteed.<br />

MANUSCRIPTS AND ART<br />

<strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine invites the submission of manuscripts,<br />

photos, art, and letters to the editor from its readers. All<br />

material submitted becomes the property of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong><br />

<strong>Patrol</strong>, unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed<br />

mailing container. Send submissions to <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine,<br />

133 S. Van Gordon St., Suite 100, Lakewood, CO 80228-1700,<br />

or via e-mail at spm@nsp.org. For more information, call<br />

(303) 988-1111.<br />

NSP WEBSITE: www.nsp.org<br />

50% TOTAL RECOVERED FIBER<br />

20% POST-CONSUMER WASTE<br />

<strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine is printed on paper with 50% recycled<br />

fibers that contain 20% post-consumer waste. Inks used<br />

contain a percentage of soy base. Our printer meets or<br />

exceeds all federal Resource Conservation Recovery Act<br />

(RCRA) standards.<br />

NSP MISSION: NSP provides quality focused education<br />

and training in safety, credentialed outdoor emergency<br />

care, and transportation services. This enables members<br />

and other stakeholders to serve the outdoor recreation<br />

community. NSP continually explores new opportunities<br />

for membership and association enhancement.<br />

NSP CORE VALUES: Excellence, service, camaraderie,<br />

leadership, integrity, responsiveness<br />

NATIONAL CHAIRMAN<br />

Bill Sachs<br />

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR<br />

Stephen M. Over<br />

NATIONAL TREASURER<br />

Ron Plumer<br />

NSP BOARD OF<br />

DIRECTORS<br />

Bill Sachs<br />

Michael Adams<br />

Bob Black<br />

John Kretschmann<br />

Nici Singletary<br />

Pamm Ferguson<br />

Bob McLaughlin<br />

Ron Plumer<br />

Julie Rust<br />

Dick Everett<br />

Larry Acord<br />

Terry LaLiberte<br />

Jessica Simpson<br />

LEGAL COUNSEL<br />

Bruce Ries<br />

GOVERNANCE<br />

COMMITTEE<br />

Bob Black, Chair<br />

Larry Acord<br />

John Kretschmann<br />

Jessica Simpson<br />

FINANCE<br />

COMMITTEE<br />

Ron Plumer, chair<br />

Michael Adams<br />

Pamm Ferguson<br />

Terry LaLiberte<br />

PLANNING<br />

COMMITTEE<br />

Dick Everett, chair<br />

Bob McLaughlin<br />

Julie Rust<br />

Nici Singletary<br />

CPM Number 40065056<br />

NATIONAL PROGRAM<br />

DIRECTORS<br />

AVALANCHE<br />

Mike Baker<br />

INSTRUCTOR DEVELOPMENT<br />

Ed Riggs<br />

OUTDOOR EMERGENCY CARE<br />

Larry Bost<br />

SKI AND TOBOGGAN<br />

Cliff Chewning<br />

MOUNTAIN TRAVEL<br />

AND RESCUE<br />

Monica Spicker<br />

SKILL DEVELOPMENT<br />

Ron Clark<br />

NSP MEDICAL<br />

DIRECTOR<br />

David Johe, M.D.<br />

NATIONAL AWARDS<br />

COORDINATOR<br />

Myer Avedovech<br />

NSP HISTORIAN<br />

Gretchen R. Besser, Ph.D.<br />

PAST NATIONAL<br />

CHAIRMEN<br />

John J. Clair<br />

(1996–2000)<br />

Jack Mason<br />

(1992–96)<br />

Marlen Guell<br />

(1986–92)<br />

Ronald L. Ricketts<br />

(1982–86)<br />

Donald C. Williams<br />

(1978–82)<br />

Charles W. Haskins<br />

(1976–78)<br />

Harry G. Pollard<br />

(1968–76)<br />

Charles W. Schobinger<br />

(1962–68)<br />

William R. Judd<br />

(1956–62)<br />

Edward F. Taylor<br />

(1950–56)<br />

Charles M. Dole<br />

(1938–50)<br />

2 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

commentary<br />

BY BILL SACHS, NSP NATIONAL CHAIR<br />

upping the<br />

quality quotient<br />

“Success is not the result of spontaneous<br />

combustion. You must set yourself on fire.”<br />

—Reggie Leach (former player for the<br />

Philadelphia Flyers hockey team)<br />

I<br />

I drove an old Buick in high school, hoping<br />

against hope that my folks would<br />

present me with a brand-new car some<br />

day. Eventually I realized it wasn’t going<br />

to happen, so I got a job and started saving<br />

for a Corvette. I never did get the convertible<br />

of my dreams, but I did learn an<br />

important lesson: Don’t let wishful thinking<br />

cloud your grasp on reality. The NSP<br />

board has demonstrated the same wisdom<br />

by committing to quality assurance<br />

efforts in all education programs.<br />

<strong>Patrol</strong>ling requires us to be disciplined;<br />

to constantly learn, re-learn, and<br />

fine-tune our patrolling skills and knowledge<br />

so we can continue to provide value<br />

to area management and the general public.<br />

It is incumbent upon us to instill in<br />

them the confidence that we can and will<br />

meet expectations. If our programs aren’t<br />

known for their quality, however, we cannot<br />

assure area management, the general<br />

public, or anyone else of our worth.<br />

“Average” doesn’t suffice in the realm of<br />

emergency care, and that’s why the NSP<br />

must provide outstanding programs and<br />

products to help its members be successful.<br />

We are challenged to do so in our<br />

vision statement: “. . . to be the premier<br />

provider of outstanding programs and<br />

services benefiting the global outdoor<br />

recreation community.”<br />

In accordance with that mandate, the<br />

national board has resolved to focus its<br />

education programs on giving members<br />

the tools they need to be successful<br />

patrollers. This is not a new philosophy<br />

for the NSP. Educational excellence has<br />

long been a standard for the organization,<br />

and we constantly work to invigorate<br />

our various programs with the most<br />

up-to-date information available. NSP’s<br />

leaders fully realize that when you are<br />

confident in your knowledge and skills,<br />

you can be confident in your actions,<br />

and that makes you a tremendous asset to<br />

the area.<br />

Although the focus on quality is not<br />

unprecedented, the snowsport consumer’s<br />

expectations continue to rise. To<br />

address those expectations (and remain<br />

in business), resorts must constantly<br />

work to improve the quality of their main<br />

product—the skiing/snowboarding experience—which<br />

obviously includes patrol<br />

services. Resorts cannot be isolated from<br />

the things that make their patrols successful,<br />

and neither can the patrollers. We<br />

have a duty to become trained so that<br />

what we do is in accordance with standards<br />

of care set by the resort.<br />

So, the NSP must zero in on the practical<br />

aspects of developing and delivering<br />

high-quality educational services. If we do<br />

this well, we will attract the interest of<br />

other outdoor groups, lending further<br />

value to NSP training and increasing the<br />

demand for NSP-trained people.<br />

The NSP’s role in training patrollers<br />

is indisputable, hence the need to assure<br />

that in all cases, our courses are of such<br />

high quality that they consistently engage<br />

and educate patrollers. The organization<br />

must address any and all weaknesses in<br />

the process, regardless of whether the<br />

course material, the instructor, or even<br />

the course setting is to blame. The lines of<br />

accountability in our organization occasionally<br />

get skewed and, unfortunately,<br />

our programs and courses suffer as a<br />

result. To keep things in better focus, the<br />

NSP board has taken on the direct<br />

accountability of the Outdoor Emergency<br />

Care Program. In December the organization<br />

sponsored a meeting that brought<br />

together division directors, national program<br />

directors, and OEC division supervisors.<br />

The meeting—the first of its<br />

kind—had one purpose: to unite the various<br />

groups in meeting member needs.<br />

Our hopes are high for the outcome of<br />

those discussions.<br />

We have direct responsibility for the<br />

material and courses offered, and to instill<br />

quality assurance in those areas, the<br />

national level will have direct control over<br />

the instructors too. Beginning with<br />

OEC—and eventually with other programs—the<br />

national organization will<br />

directly oversee the instructors. As delegated<br />

by the NSP board, the delivery of<br />

NSP programs will remain the purview of<br />

the divisions and the individual patrol<br />

representatives, but instructor accountability<br />

to the national level will increase the<br />

chances of maintaining excellence in<br />

NSP’s educational offerings.<br />

The board of directors is charged<br />

with making the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> a<br />

premier provider of outstanding programs<br />

and services, for each and every<br />

member. The organization must be<br />

accountable, flexible, and inventive in all<br />

things, and yet individual patrollers must<br />

also do their part to remain well-trained<br />

and current in their knowledge and skills.<br />

I am truly optimistic that our collective<br />

efforts will heighten our commitment as<br />

much as our perceptions of what we must<br />

do. <strong>Patrol</strong>lers have never been known to<br />

shy away from hard work. The fact is, our<br />

organization and our members are highly<br />

valued in their respective roles, but we<br />

know we have to earn it. ✚<br />

4 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

letters<br />

spm@nsp.org<br />

<strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine welcomes your views.<br />

Letters to the editor should be typed and must include your full name, address, and daytime telephone<br />

number. (<strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine does not publish anonymous letters.) Submit correspondence by fax to<br />

800-222-4754 or 303-988-3005, by e-mail to spm@nsp.org, or by conventional mail to <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong><br />

Magazine, 133 South Van Gordon Street, Suite 100, Lakewood, CO 80228-1700. Letters will be published<br />

as space permits and may be edited for clarity, style, and length.<br />

AVERTING DISASTER<br />

Iread with great interest your article on adaptive<br />

skiers and the challenge of evacuating<br />

adaptive equipment from a stalled chairlift (“Lift<br />

Evacuation: Adapting to the Adaptive <strong>Ski</strong>er,” fall<br />

2004). Some years ago we gave this very issue<br />

considerable thought during our annual chairlift<br />

evacuation training and came to one major conclusion<br />

that was not cited in the SPM article.<br />

We do not yet have a substantial number of<br />

adaptive skiers at the four resorts we serve on<br />

Mount Hood, and most of those who do visit us do<br />

not own their equipment. Loaner programs at<br />

local hospitals allow adaptive athletes to try various<br />

sports using borrowed equipment. This means<br />

that an adaptive device may not be a perfect fit<br />

for the individual.<br />

This fact caused us to think seriously about<br />

lowering adaptive guests some 20 to 50 feet from<br />

a chairlift. Our conclusion was to always make sure<br />

that both the guest and the adaptive device are<br />

securely attached to our rescue rope. The last<br />

thing we would want is for an adaptive athlete to<br />

lose his or her grip on or balance in the adaptive<br />

device and fall out of it during descent. In theory<br />

the harness provided with the adaptive equipment<br />

should keep the athlete right-side-up, but if<br />

weight shifts or our guest panics, we want to be<br />

sure to have a secure tether to the person as well<br />

as the adaptive device, so neither one falls.<br />

Thankfully, the lifts on Mount Hood rarely<br />

experience serious malfunctions and chairlift evacuation<br />

is seldom necessary, but as patrollers we<br />

need to be prepared to assist all of our guests,<br />

including those adapting to a sport that’s long been<br />

exclusive to able-bodied athletes.<br />

Thank you for the informative and often brilliant<br />

articles you bring to the patrolling community.<br />

MAC SHELDON<br />

MOUNT HOOD SKI PATROL, OR<br />

CORRECTION<br />

Due to an editing error, Lee T. Wittman’s article<br />

“Lift Evacuation: Adapting to the<br />

Adaptive <strong>Ski</strong>er” (fall 2004) implied that the<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> recruited members of the Tenth<br />

Mountain Division upon their return from World War<br />

II.<br />

Some, but not all, of the original members of<br />

the Tenth were early patrollers. Many of the<br />

returning soldiers-on-skis did in fact swell the<br />

ranks of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> after they were<br />

demobilized. However, there was no active<br />

recruitment on the part of the NSP. <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong><br />

NSP <strong>National</strong> Office<br />

133 S. Van Gordon St.<br />

Lakewood, CO 80228<br />

303-988-1111<br />

US-6<br />

Van Gordon St<br />

Union Blvd<br />

2nd Ave<br />

Simms St<br />

4th Ave<br />

How to find us Next time you’re in the area, stop by and visit the national office.<br />

93<br />

To Boulder<br />

To Boulder<br />

US-36<br />

To Fort Collins<br />

I-76<br />

I-270<br />

N<br />

DIA<br />

Airport Blvd<br />

IDAHO<br />

SPRINGS<br />

Cedar Dr<br />

Zang Way<br />

Alameda Pkwy<br />

ROCKY<br />

MOUNTAINS<br />

EVERGREEN<br />

US-6<br />

To snowsports<br />

I-70<br />

To snowsports<br />

58<br />

GOLDEN<br />

To snowsports<br />

US-285<br />

US-6<br />

Union Blvd<br />

Kipling St<br />

LAKEWOOD<br />

Wadsworth Blvd<br />

Alameda Ave<br />

38th Ave<br />

Sheridan Blvd<br />

Federal Blvd<br />

Santa Fe<br />

I-25<br />

DOWNTOWN<br />

DENVER<br />

Speer<br />

Broadway<br />

Blvd<br />

University Blvd<br />

Colorado Blvd<br />

Colfax Ave<br />

6th Ave<br />

1st Ave<br />

Belleview Ave<br />

Mississippi Ave<br />

Hampden Ave<br />

I-25<br />

Havana St<br />

I-70<br />

I-225<br />

DENVER<br />

TECH CENTER<br />

Peña Blvd<br />

E470<br />

US-85<br />

County Line Rd<br />

To Colorado Springs<br />

C470<br />

C470<br />

6 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

June Mountain<br />

<strong>Patrol</strong> A Quality Crew<br />

By Ingrid Tistaert<br />

in the <strong>Sierra</strong>s<br />

There’s nothing unusual about the gravitational pull at<br />

June Mountain, a 550-acre snowsports area that sits high<br />

in California’s Eastern <strong>Sierra</strong> Nevada. And the gold that<br />

once drew prospectors to these hills is largely tapped out. So<br />

there must be some other explanation for why many of June’s<br />

patrollers gladly commute upwards of seven hours—one-way—<br />

from the Los Angeles Basin to ply their skills here each weekend.<br />

Well, it could be the snow (more than 20 feet per year) or the<br />

diversity of terrain (chutes, steeps, and what is considered one of<br />

the biggest and best terrain parks in the region). But ask any of<br />

the area’s 34 patrollers, and they’ll tell you a major draw is the<br />

caliber of their colleagues.<br />

Garry Larson, a 20-year patrolling veteran from Southern<br />

California, joined the June Mountain gang five years ago, and<br />

he’s happy he made that choice. Larson commits to a 320-mile<br />

drive from San Dimas because he appreciates “the professional<br />

environment in the June patrol room.” Of course, he can’t help<br />

but add, “The benefits of working at a challenging mountain<br />

with lots of snow far outweigh the long drives.”<br />

“June is one of those patrols where you don’t want to let anybody<br />

down, so everybody just works harder and harder,” explains<br />

June Mountain patroller (and NSP board member) Larry Acord.<br />

“This is an unusual group of people; I’ve only seen one or two<br />

other groups with such amazing synergy.”<br />

You’ll get no argument on that point from <strong>Patrol</strong><br />

Representative Steve Francisco. “This tight-knit group works<br />

together as a team with seamless integration between the paid<br />

and volunteer patrollers,” he says proudly. “The volunteers willingly<br />

travel over 600 miles on weekends, and the paid patrollers<br />

have all become active NSP members in the past two years,<br />

demonstrating a high level of dedication.”<br />

With this kind of camaraderie and devotion to purpose, it<br />

should come as no surprise that the June Mountain <strong>Patrol</strong> won the<br />

NSP’s <strong>National</strong> Outstanding Small Alpine <strong>Patrol</strong> Award for the<br />

2003–04 season. What is somewhat unusual is the speed with<br />

which the patrol put together such a remarkable crew. Up until<br />

four years ago, the June Mountain <strong>Patrol</strong> was a much smaller paid<br />

team that filled all of its shifts by rotating patrollers from June’s sister<br />

area, Mammoth Mountain. Then in 2001, <strong>Patrol</strong> Director Eric<br />

Diem and Carl Williams—who’d recently come on board as<br />

mountain manager—reached the conclusion that it might be a<br />

good idea to have a consistent cadre of patrollers every weekend.<br />

Enter Stan Kelley.<br />

Kelley, a longtime NSP member from Southern California,<br />

was on his way to Tahoe a few years back when he decided to stop<br />

for the day and ski at June Mountain. While he was on the hill,<br />

he struck up a conversation with Diem, who mentioned that<br />

June was interested in taking on some volunteer patrollers to<br />

share on-hill duties on the weekends. Kelley called up long-time<br />

friend (and Southern California Region Director) Mark Giebel.<br />

To make a long story short, the three men met with mountain<br />

manager Williams, and in 2001 June Mountain welcomed NSP<br />

patrollers, one of whom was Kelley—destined to become the<br />

area’s first patrol representative. (He’s still one of the patrol’s goto<br />

guys, handling everything from collecting patrol dues to lining<br />

up lodging for those commuting patrollers.)<br />

Thus began a beautiful relationship between the volunteers<br />

and paid staff at June. The numbers now stand at 23 volunteer<br />

and 11 paid patrollers. And, as Francisco points out, every one<br />

of them is now a member of the NSP, making June Mountain<br />

the only patrol in the region in which all of the paid and volunteer<br />

patrollers are affiliated with the NSP.<br />

Says June Mountain patroller Cirina Catania,“It’s a continuing<br />

source of pride for all of us to see the NSP logo on each and every<br />

patrol jacket and proudly visible on the signage at the resort.”<br />

The success of the June patrol is bolstered by its healthy relationship<br />

with the mountain manager. Francisco and Williams<br />

CONTINUED<br />

8 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

ERIC DIEM<br />

CALIFORNIA<br />

Sacramento<br />

San Francisco<br />

June<br />

Mountain<br />

Pacific Ocean<br />

Santa Barbara<br />

Los Angeles<br />

ERIC DIEM<br />

VITAL STATISTICS<br />

Above right: During a Senior toboggan training run, Ian Doleman<br />

(front operator) and Reeve Colfesh (tail rope operator) transport<br />

visiting patroller Keith Tatsukawa down a steep, powdery bump<br />

field. Above: Members of the June patrol practice a probe line<br />

during a spring avalanche training course.<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

June Mountain’s average<br />

snowfall is 250 inches.<br />

The average percentage<br />

of sunny days per season<br />

is 70 percent.<br />

The area’s vertical drop is<br />

2,590 feet, with a 10,090-foot<br />

summit and a 7,545-foot<br />

base.<br />

Located 20 miles north<br />

of Mammoth, California,<br />

June Mountain has 35<br />

trails serviced by seven<br />

quads, four doubles, and<br />

one rope tow. The terrain<br />

is 20 percent advanced,<br />

45 percent intermediate,<br />

and 35 percent beginner.<br />

The area’s terrain park,<br />

affectionately known as<br />

JM2, has been open for<br />

three seasons and boasts<br />

a superpipe and three<br />

terrain-enhanced areas<br />

with features for athletes<br />

of all abilities.<br />

The mountain officially<br />

opened on February 12, 1961<br />

(Lincoln’s birthday).<br />

W inte r 2005 | <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine 9

❚ CONTINUED FROM PAGE 8<br />

speak on a regular basis and, according to Francisco, both<br />

the patrol and area management share NSP’s vision of safety<br />

and service.<br />

June Mountain is no behemoth like the aptly named<br />

Mammoth Mountain just down the road, but patrollers still have<br />

plenty of gnarly terrain to master and lots of patients to transport<br />

down the mountain. With a vertical drop of 2,590 feet and<br />

a terrain distribution of 20 percent advanced, 45 percent intermediate,<br />

and 35 percent beginner, June Mountain is no<br />

pushover. Neither are its patrollers.<br />

When asked to name patrollers who were particularly noteworthy<br />

at June Mountain, Francisco hems and haws. It’s not<br />

because he has a hard time finding extraordinary patrollers, it’s<br />

because everyone puts extraordinary effort into making this<br />

patrol what it is, says Francisco. “It’s very difficult to choose,<br />

because everyone on this patrol contributes so much,” he<br />

explains. Obviously, Francisco, as a good leader, places importance<br />

on every member of his patrol, not just the best skier or the<br />

most experienced OEC provider. He’s a leader who treats patrol<br />

members with fairness and shows his appreciation for the duties<br />

they perform.<br />

A Senior patroller and winner of the NSP’s <strong>National</strong><br />

Outstanding Administrator Award in 2003, Francisco has<br />

upwards of 30 years of patrol experience, having spent time at<br />

eight different areas on both the East and the West Coasts—and<br />

he says he feels that the June Mountain patrol is one of the<br />

strongest groups with which he’s worked. He is quick to bestow<br />

credit upon <strong>Patrol</strong> Director Diem, who has accumulated 22 years<br />

of experience, 17 of which have been as June Mountain’s patrol<br />

director. “Eric is the spark that lights the fire and gets everyone<br />

pumped up,” Francisco says. “He is the inspiration of the patrol.<br />

He leads by example and expects excellence.”<br />

Diem takes ski runs with everyone, and, according to<br />

Francisco, “watching him just inspires you to work hard and<br />

improve. He makes you want to be the best patroller you can be.”<br />

Fellow patroller Acord clearly agrees. “Eric’s number one mission<br />

is to get the patrol fired up,” he says. “You can’t wait to go<br />

out there and work hard for the guy. The best analogy I can think<br />

of is ‘Top Gun School.’”<br />

Diem—an NSP Certified patroller—concedes that he’s a<br />

“high energy person by nature” and that he consciously “sends a<br />

positive message to the other patrollers.” He feels that this gives<br />

them the confidence necessary to perform in critical situations.<br />

(In addition to being a driving force behind the patrol’s success<br />

and subsequent national award, Diem picked up a little hardware<br />

of his own in 2004 when he was named <strong>National</strong><br />

Outstanding Paid <strong>Patrol</strong>ler.)<br />

Together, Francisco and Diem make an excellent team, which<br />

is probably why patrol members sometimes refer to the representative<br />

and director collaboratively as “The Steve and Eric<br />

Show.” In addition to their administrative duties, they spend a<br />

fair amount of time leading classes and clinics. Francisco is an<br />

instructor and instructor trainer in the OEC, Alpine Toboggan,<br />

and Instructor Development disciplines, and Diem teaches OEC,<br />

Avalanche, and Alpine Toboggan classes. The men are in good<br />

company as June Mountain’s patrol also boasts nine Senior evaluators,<br />

five Certified evaluators, three OEC instructor trainers,<br />

thirteen OEC instructors, and four <strong>Ski</strong> and Toboggan instructors<br />

(one of whom is a <strong>Ski</strong> and Toboggan instructor trainer).<br />

Approximately 20 percent of the patrol has attained NSP’s<br />

Certified classification with another 20 percent registered as<br />

Seniors. Oh, and seven of the 34 patrol members (more than<br />

20 percent) have <strong>National</strong> Appointments.<br />

When it comes to training, Diem pursues a creative and<br />

active curriculum from which June Mountain patrollers greatly<br />

benefit. Every Saturday and Sunday morning he conducts training<br />

sessions to enhance the skills of the patrollers. These hourlong<br />

sessions cover everything from OEC proficiency to<br />

avalanche awareness, lift evacuation, and toboggan handling. He<br />

also holds regular enhancement clinics in the evenings to help<br />

the crew brush up on their overall patrolling knowledge. Diem<br />

frequently brings in guest lecturers too. For instance, local EMS<br />

doctors have led training clinics about head injuries and bone<br />

fractures, hydrologists have taught snow science, and meteorologists<br />

have lectured on the various nuances of weather in the<br />

mountain environment.<br />

With this attention to training, June Mountain patrollers are<br />

clearly mindful of the need to be skillful, prepared, and versatile.<br />

And they seem to thrive on their roles as caregivers, from the<br />

longest-tenured veteran to the new recruits.<br />

Among those with considerable time invested in patrolling are<br />

Steve Reneker, a volunteer, and Chris Lizza, a paid patroller. Having<br />

patrolled at four different areas over the past 27 years, Reneker says<br />

he feels a certain obligation to share knowledge he’s gained from<br />

others. He serves as an inspiration for fellow patrollers—and with<br />

good reason, for he tends to be successful at whatever he sets his<br />

mind to. There was, for example, that climb up Mount Everest in<br />

1995. After spending two years in strict training for the endeavor,<br />

Reneker then bid his family a bittersweet adieu and spent three<br />

months in the Himalayas, hauling some six tons of gear up and<br />

down between six camps on the north side of Everest.<br />

Reneker compares mountain climbing to patrolling and<br />

emphasizes the importance of having a strong team in either<br />

endeavor. “You are only as good as those who surround you,” he<br />

says, noting that in the case of Mount Everest, he was successful<br />

only because of his fellow team members, good health, and<br />

agreeable weather.“Although I’ve been patrolling for a long time,<br />

I still get an adrenaline rush from helping skiers and ’boarders<br />

and learning new techniques to better myself and others around<br />

me,” he adds.<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 14<br />

10 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

ERIC DIEM<br />

ERIC DIEM<br />

Above: Proud patrollers at June<br />

pose atop their beloved <strong>Sierra</strong><br />

<strong>Ski</strong> Hill with a trophy awarded by<br />

the southern california Region.<br />

Left: Evening lift evac training<br />

at June is a regular occurrence.<br />

<strong>Patrol</strong> director Eric Diem and<br />

patrol Representative Steve<br />

Francisco insist their team stay<br />

up-to-date and fresh on all rescue<br />

procedures. Below: patrol director<br />

Eric diem (right) and June’s unsung<br />

hero chris Lizza exchange ideas<br />

at a summer OEC refresher course.<br />

STEVE FRANCISCO<br />

W inte r 2005 | <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine 11

❚ CONTINUED FROM PAGE 10<br />

He also says his experience as a mountaineer assists him in<br />

his patrolling, because it provides a level of confidence in his<br />

skills and allows him to understand his limitations. “<strong>Ski</strong><br />

patrolling has also taught me how to travel safely in a winter<br />

environment and to be able to survive the coldest of nights with<br />

minimal gear,” he points out.<br />

When asked to share what inspires him about his fellow<br />

patrollers, Reneker explains that patrolling with volunteers with<br />

different backgrounds is very rewarding. “Seeing people give up<br />

their weekends to help ensure a safe and fun experience for the<br />

public has given me an appreciation for everyone in NSP,” he<br />

says. “My best friends are those I have gained in the ski patrol,<br />

and I consider them to be part of my extended family.”<br />

If there’s an unsung hero on the patrol, it is probably Lizza,<br />

who’s called patrolling a profession for more than 20 years (five<br />

at June, 15 at Mammoth, and a few years tossed in at Crystal<br />

Mountain in Washington and Las Leñas in Argentina). Diem<br />

speaks highly of him, saying Lizza has the ability to look at the<br />

big picture instead of what’s in front of him, which gives him a<br />

great eye for risk management—a key characteristic of a good<br />

patroller. Lizza grew up in the Central <strong>Sierra</strong>s and was a junior<br />

racer at Mammoth Mountain. He nonchalantly points out that<br />

he “knows June Mountain pretty well and can get anywhere<br />

pretty quick.” Translation: This guy is a great skier. But the<br />

impressive qualities don’t stop there. If you happen to have a<br />

copy of his book, The South American <strong>Ski</strong> Guide, you might<br />

know that this patroller with a penchant for ski history is also a<br />

skillful writer.<br />

Some might say that the majority of ski and snowboard<br />

patrollers are determined—after all, these people have a great<br />

deal of responsibility on the hill and in the aid room. But every<br />

so often a patroller demonstrates such “stick to it-ness” that he<br />

or she accomplishes remarkable feats in the face of insurmountable<br />

odds. Meet Patty Giebel, a 25-year patrolling veteran and<br />

prime example of a patroller who goes above and beyond the<br />

usual levels of determination.<br />

Take, for instance, the time she was attending Certified-level<br />

evaluations at Mammoth Mountain. During one of the clinics<br />

Giebel developed appendicitis and was whisked immediately<br />

down the hill to the hospital. Doctors removed her appendix that<br />

day, but instead of begging off on the clinic—as most people<br />

would do after surviving this experience—she returned to the hill<br />

the next day and passed her avalanche exam with flying colors.<br />

As if this scenario doesn’t prove the point, there are others<br />

that are perhaps even more impressive. In early 2004 Giebel was<br />

in a serious bike accident in which she sustained a broken nose<br />

and neck and stopped breathing. Fortunately her husband,<br />

Mark, happened to be with her, and was able to maintain her<br />

spinal alignment and keep her airway clear until more help could<br />

arrive. After the accident Giebel was placed in a halo to support<br />

her neck. Two weeks later, instead of calmly recuperating at<br />

home, she went to Squaw Valley, California, to attend yet another<br />

Certified clinic.<br />

One of Giebel’s passions outside of patrolling is endurance<br />

running, and nothing seems to get in the way of that rigorous<br />

pursuit. Despite her condition she decided to train for a big race<br />

from Agoura, California, to San Diego, California, a 60-mile,<br />

12-hour run. While still in her halo, Giebel worked out as she<br />

normally would—running, trail running, and doing strength<br />

training. Doctors eventually let her graduate from the halo to a<br />

hard C-collar. Two weeks later she entered the race and not only<br />

completed the run but won first place in the woman’s field and<br />

second place overall in both the mens’ and women’s divisions, a<br />

rare feat for a woman in prime condition (let alone one with a<br />

broken neck).<br />

With folks like Francisco, Diem, Reneker, Lizza, and Giebel<br />

around, it’s not difficult to imagine that new patrollers at June<br />

Mountain have good mentors. Then again, some just take to<br />

patrolling naturally. One such newbie is Tony Golden. The<br />

2003–04 season was his first as a patroller, but you wouldn’t<br />

guess it from accolades he receives from Francisco: “Tony is a<br />

self-starter who tackles projects with enthusiasm and completes<br />

them competently, requiring little or no direction.” Golden<br />

shrugs off his hard work, saying “I’m just into it.”<br />

That much is clear. Golden completed his candidate training<br />

within his first month of patrolling at June, spending 12 days on<br />

the mountain in the first 20 days the area was open. Overall, during<br />

the 2003–04 season, he devoted more than 400 hours to the<br />

June Mountain <strong>Patrol</strong> in on-hill and off-hill duty time.<br />

Golden asserts that his experience at June Mountain has<br />

taught him a lot in just a short time.“From the beginning I’ve been<br />

placed in the ‘deep end,’ working scenes right from the get-go.”<br />

Originally from the East Coast, where he grew up skiing in<br />

the ’60s at a small resort with a strong family atmosphere,<br />

Golden says he is looking to recreate this feeling with his family,<br />

and June Mountain is just the place to do it. Hence, he had a<br />

hand in recruiting his wife, Lynn, to also help out at the area. Full<br />

of positive energy and a real go-getter in her own right, Lynn<br />

helped initiate June’s mountain host program and served as one<br />

of the area’s four original mountain hosts during the 2003–04<br />

season.“June is special because they care about every person who<br />

comes to the mountain,” she says.<br />

Clearly, they’re doing something right at June Mountain.<br />

Between the camaraderie, training, and downright dedication to<br />

making a safer go of the slopes they love, area management and<br />

this small group of patrollers work magic in the shadows of<br />

Mammoth. And while big sister might be more well-known,<br />

little sister June is no wallflower. ✚<br />

Ingrid Tistaert, former assistant editor for <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine, now works as a<br />

freelance writer and editor. She lives in Tahoe City, California.<br />

14 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

Right: Patrick Wood<br />

(left), and Steve<br />

Francisco (right) carry<br />

fellow patroller Dave<br />

Green on a spineboard<br />

during a training clinic.<br />

Below left: The June<br />

Mountain <strong>Patrol</strong> will<br />

now need to make room<br />

alongside its region<br />

trophy for the <strong>National</strong><br />

Outstanding Small<br />

<strong>Patrol</strong> Award. Below<br />

right: Long-time<br />

patroller and mountaineer<br />

steve reneker<br />

on the summit of<br />

Mt. Everest in 1995.<br />

ERIC DIEM<br />

PHOTO CREDIT<br />

Above: need caption need caption<br />

need caption need caption need<br />

caption need caption. Right: need<br />

caption need caption need caption<br />

need caption need caption<br />

need caption need caption need<br />

caption need caption. Below:<br />

<strong>Patrol</strong> director Eric Diem caption.<br />

ERIC DIEM<br />

COURTESY OF STEVE RENEKER<br />

W inte r 2005 | <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine 15

B R A C<br />

<strong>Ski</strong>s? CHECK!<br />

Boots? CHECK!<br />

Poles? CHECK!<br />

Tension strain-reduction<br />

knee brace? CHECK!<br />

F<br />

Knee Injuri<br />

or millions of skiers and other sports enthusiasts,<br />

the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is<br />

as vulnerable as Achilles’ heel. As a patroller, you’ve<br />

probably seen a fair number of knee injuries in your<br />

time.You may have even been the victim of knee problems<br />

yourself, collapsing to the snow and writhing<br />

in pain after the telltale “pop” heard ’round the mountain<br />

tells you, unmistakably, that you’ve joined the<br />

ranks of the nearly<br />

176,000 people in<br />

the United States<br />

who suffer ACL ruptures<br />

each year. And<br />

if you aren’t one of<br />

those people, is it<br />

just a matter of time<br />

before you are?<br />

By Michael Patmas, MD<br />

What The Experts Say<br />

hese days, roughly 50,000 ACL<br />

T<br />

reconstructions are performed each<br />

year. With good rehabilitation, 85 to 92<br />

percent of people who undergo surgery<br />

will recover fully and eventually return to<br />

full sports participation, according to the<br />

American Association of Orthopedic<br />

Surgeons. Few would disagree that bracing<br />

the knee after injury and surgery can<br />

aid the recovery process by offering structural<br />

support, at least until the ligament<br />

heals and surrounding leg muscles are<br />

strengthened through rehabilitation.<br />

But, is there a way to prevent a recurrence<br />

of the injury—or even keep it from<br />

happening the first time? By adding a knee<br />

brace to our regular arsenal of equipment<br />

and mountain gear, such as custom-fit<br />

boots and top-of-the-line bindings, can we<br />

16 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

E YOURSELF<br />

s May Be Preventable<br />

lower our risks of ACL injury? Most doctors<br />

and athletic coaches say no, that wearing<br />

a brace after rehab only encourages the<br />

muscles to slack off and become dependent<br />

on the brace. After two ACL tears and<br />

subsequent surgeries, however, I began to<br />

wonder if maybe conventional wisdom<br />

was missing something that poor luck and<br />

experience understood all too well.<br />

A Few Days In The Life<br />

fter my first ACL injury and subsequent<br />

reconstructive surgery in the<br />

A<br />

spring of 1999, I wore a DonJoy<br />

“Defiance” knee brace while skiing for<br />

two seasons. The brace is designed to prevent<br />

the femur from moving excessively<br />

in a fore/aft plane on top of the tibia. That<br />

type of movement puts strain on the ACL<br />

and, during a fall, collision, or simple<br />

twisting movement, can be the cause of a<br />

ligament rupture. In effect, the brace does<br />

what the leg muscles are supposed to do,<br />

which is reduce strain on the ligament.<br />

Eventually, after I regained leg strength<br />

and completed rehabilitation, my ski buddies<br />

told me to stop wearing the brace<br />

lest I grow too dependent on it. They said<br />

that wearing the brace too long would<br />

keep my muscles from getting strong<br />

enough to support the knee on their own.<br />

So, I retired the brace to the back of my<br />

cluttered equipment closet and skied well<br />

and mostly pain-free for another year and<br />

a half. I figured my leg muscles were doing<br />

their job to reduce any harmful strain on<br />

the ACL. As a ski instructor, I have a passion<br />

for being on the snow, and didn’t<br />

want to stay off it any longer than I had to.<br />

Then one day, doing an otherwise<br />

ordinary turn, I glanced back over my<br />

shoulder to be sure my class was behind<br />

me and got just a little off balance.<br />

Suddenly I felt a definite, uncomfortable<br />

tearing sensation. It was certainly not the<br />

loud pop with explosive pain that I experienced<br />

the first time I injured my ACL,<br />

and I was able to continue skiing. I<br />

assumed I hadn’t completely torn the ligament<br />

again, though I knew I had done<br />

something. My knee didn’t hurt; it just<br />

felt slightly wobbly.<br />

The following day I saw Dr. Stephan<br />

Tarlow, a Portland knee surgeon, who<br />

ordered an MRI. Both Dr. Tarlow and the<br />

radiologist indicated that I had torn the<br />

ACL graft, and they recommended taking<br />

some time off. They obviously did not<br />

know me and didn’t realize that the words<br />

“time off” aren’t in my vocabulary. I<br />

should have listened, but I’m admittedly<br />

stubborn and slow to learn. I actually<br />

convinced myself that my doctor was<br />

wrong, that it wasn’t as bad as he said it<br />

was. This deep sense of denial was probably<br />

rooted in the fact that, at that time, I<br />

was already registered for the PSIA Alpine<br />

Level III exam and did not want to cancel.<br />

Still convinced I had only sustained a<br />

bad knee “sprain,” I put the brace back on,<br />

looking for a little extra support, and went<br />

about my season. Even with the brace, I<br />

had some pain and felt limited, not by the<br />

brace itself but by my insecurities. Ironically,<br />

I found myself skiing more accurately<br />

because I was more aware of my fore/aft<br />

stance and balance. I was skiing better and<br />

cleaner, though less aggressively. I even<br />

passed the Level III exam a few months<br />

later, although my knee did hurt after a full<br />

day of skiing.“Who needs an ACL anyway,”<br />

I chuckled to myself. “It’s a highly overrated<br />

ligament.” My success only further<br />

convinced me that I had been right and my<br />

doctors wrong. Perhaps I had torn the<br />

graft, but there must have at least been a<br />

few fibers left holding everything together.<br />

The following autumn I fulfilled a<br />

dream by participating in a fantasy baseball<br />

camp with retired World Series slugger<br />

Dave Henderson. That was huge fun!<br />

But while playing second base I fielded a<br />

CONTINUED<br />

W inte r 2005 | <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine 17

A bracing thought: Would the author have<br />

avoided a second ACL tear if he hadn’t retired<br />

his brace to the back of the closet after rehab<br />

got him back on skis?<br />

PHOTOS COURTESY OF MICHAEL PATMAS, MD<br />

❚ CONTINUED FROM PAGE 17<br />

ground ball and pivoted on my left leg to<br />

throw out a runner at home. My knee<br />

buckled like a sapling in gale force winds.<br />

I wasn’t wearing my brace at the time, and<br />

I knew at that moment that a second ACL<br />

reconstruction was inescapable. Whatever<br />

fibers might have been left after the tear<br />

the previous winter were certainly gone<br />

now. But by then I had lost my window of<br />

opportunity to have surgery before the<br />

ensuing ski season.<br />

As if possessed by the voice of folly, I<br />

actually opted to ignore the injury yet<br />

again. I knew that during the previous<br />

season the brace served as a great “external<br />

ACL” to make up for my damaged internal<br />

one. So, after going back to the closet to<br />

retrieve the brace, I completed the entire<br />

season without the ligament. My skiing<br />

did suffer, though. I found myself up<br />

against a psychological barrier: I couldn’t<br />

“let it rip,” so to speak.<br />

The doctors admitted that I could,<br />

conceivably, ski on my bad knee longer<br />

without having surgery, but I would eventually<br />

develop accelerated degenerative<br />

arthritis, which might limit me even more<br />

than the injury itself. So, I made the decision<br />

to have surgery one more time at the<br />

end of the season. I’m only 52 . . . a kid;<br />

I’m not ready to stop playing.<br />

My second surgery was a breeze. The<br />

doctor told me that, amazingly, all that<br />

was left of the first graft were a few hairlike<br />

fronds. The graft hadn’t torn, it had<br />

completely dissolved. What was even<br />

more amazing was that my meniscus was<br />

totally intact and unharmed. For the past<br />

season and a half, I had truly been skiing<br />

without an ACL. Typically, in such a situation<br />

the other knee structures will suffer<br />

additional damage, but I had none, most<br />

likely because the brace prevented the<br />

bones and other ligaments from rubbing<br />

against one another.<br />

Using a piece of my own hamstring,<br />

the doctors created and attached an ACL<br />

graft. Hopeful that the new graft would<br />

survive, they gave me a good prognosis<br />

after the second surgery. I was walking<br />

without crutches within a week, and after<br />

two weeks I was back in the gym and have<br />

been working out everyday since. I took<br />

classes—step, powerflex, running, spinning,<br />

weight training—effectively conducting<br />

my own physical therapy.<br />

The specter of another ACL reconstruction<br />

got me thinking about what I<br />

could do to avoid having to go through<br />

this a third time. My brace had served me<br />

well during two seasons without an ACL.<br />

Maybe I should never have taken it off,<br />

despite what the “experts” said. If I had<br />

been wearing it that day on the mountain<br />

and later at the baseball camp, maybe this<br />

wouldn’t have happened again. I found<br />

myself wondering, Is there any evidence<br />

that bracing can prevent re-rupturing<br />

the ACL? If so, why did all the experts<br />

and literature advise against it? I stopped<br />

wearing the brace after the first injury<br />

because conventional wisdom said I<br />

would become dependent on it. As it turns<br />

out, dependency might have been a better<br />

alternative. Had I done some more research<br />

back then, I might have continued wearing<br />

the brace.<br />

What The Researchers Say<br />

y quest for more information didn’t<br />

M take long at all, and what I found<br />

was quite interesting. This is a very controversial<br />

area with deeply held opinions<br />

and conflicting studies. What follows is an<br />

overview of the current evidence on the<br />

role of functional bracing in protecting<br />

the ACL-reconstructed knee, with particular<br />

emphasis on the skier.<br />

Despite more than 20 years of<br />

research, the role of knee bracing remains<br />

the subject of intense debate. Some doctors<br />

believe the brace should be worn while skiing<br />

for about one year after ACL reconstructive<br />

surgery to allow the ligament<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 20<br />

18 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

The researchers fou<br />

❚ CONTINUED FROM PAGE 18<br />

graft to “mature.” The brace prevents<br />

excessive strain and allows the injured person<br />

to continue participating in sports.<br />

Others feel that the sooner a patient retires<br />

the brace the better, so the leg muscles surrounding<br />

the knee don’t weaken further<br />

from nonuse and then become dependent<br />

on the brace for strength.<br />

Eric Schlopy, a top American ski racer<br />

now back on the race scene after ACL<br />

reconstruction, put it this way when I<br />

asked his opinion. “I’m looking at the top<br />

30 skiers out there . . . nearly all have had<br />

an ACL injury, and there’s not a brace<br />

among them. My leg muscles are my<br />

brace,” he says.<br />

Schlopy’s is the dominant view, and if<br />

you’ve ever seen a racer’s thighs, you’d<br />

understand where that confidence comes<br />

from. Competitive skiers strive to rehabilitate<br />

their injuries to full working order so<br />

they can count on their bodies to win<br />

races for them rather than depend on<br />

equipment that might jeopardize their<br />

form and technique. By bringing their leg<br />

muscles back to pre-injury strength, they<br />

hope to ensure their ACLs are protected<br />

without relying on support from braces,<br />

which can be restricting and cumbersome.<br />

However, regardless of whether or<br />

not a skier is a professional athlete, if he or<br />

she ruptured an ACL the first time while<br />

in good shape, he or she is certainly at the<br />

same or better risk of doing it again, even<br />

after rehabilitating completely.<br />

So what about the rest of us mere<br />

mortals who lack the benefit of worldclass<br />

racer training and giant sequoia-like<br />

thighs? Does bracing offer us any protection<br />

against first or subsequent injuries?<br />

Interestingly, I discovered that many college<br />

football players are wearing ACL<br />

braces prophylactically. More than 80<br />

percent of linemen and 50 percent of<br />

linebackers in the Big Ten athletic conference<br />

wear braces during games and practice.<br />

Bracing reduced knee injuries from<br />

3.4 to 1.4 per thousand athletic encounters<br />

(i.e., games, practices, scrimmages)<br />

among college football players, according<br />

to one large study. The popularity of prophylactic<br />

bracing in college football is<br />

rapidly growing as more players and<br />

coaches become convinced by declining<br />

rates of injury.<br />

But in the snowsports realm, skiers<br />

may be a few turns behind. In 1997, Dr.<br />

Peter Nemeth and colleagues from the<br />

University of Ottawa published a study<br />

involving six expert ski racers with ACL<br />

injuries for whom they measured leg<br />

muscle contraction patterns while the<br />

athletes were braced and unbraced. The<br />

researchers found a clear difference indicating<br />

that bracing increased knee stability<br />

both subjectively (how it felt to the<br />

athlete wearing the brace) and objectively<br />

(the measurable strain/pressure on the<br />

joint) as suggested by the pattern and<br />

timing of muscle contraction during skiing.<br />

The study shows that bracing<br />

increases knee stability, regardless of the<br />

state of the ACL.<br />

Perhaps the most interesting data<br />

comes from the work of Dr. Bruce<br />

ACL ACL strain (%) (%)<br />

10<br />

10<br />

standing at 30° unbraced<br />

standing at 30° unbraced<br />

5<br />

standing at 30° braced<br />

standing at 30° braced<br />

0<br />

seated at 30° unbraced<br />

-5<br />

seated at 30° unbraced<br />

-5<br />

seated at 30° braced<br />

-10<br />

seated at 30° braced<br />

-10<br />

20 40 60 80 100 120 140<br />

0<br />

Anterior<br />

20<br />

load<br />

40<br />

applied<br />

60 80<br />

to tibia<br />

100<br />

(in<br />

120<br />

newtons)<br />

140<br />

Anterior load applied to tibia (in newtons)<br />

Beynnon, at the University of Vermont,<br />

who placed a strain measurement transducer<br />

directly into an ACL at surgery and<br />

tested the effect of the brace on the graft<br />

(fig.1). As was clearly shown, bracing substantially<br />

reduces strain on the ACL when<br />

loads are applied anteriorly (forward).<br />

This is the same type of strain that might<br />

cause a skier to rupture the ACL. While a<br />

brace won’t prevent a skier from falling or<br />

tweaking the knee, the research does suggest<br />

that it could share the knee’s burden<br />

and make those anteriorly directed loads<br />

less threatening.<br />

This is considered important during<br />

the rehabilitation phase after ACL reconstruction.<br />

When the new graft is placed in<br />

the knee the body reacts by breaking it<br />

down, making it vulnerable to re-injury<br />

and stretching. The graft actually weakens<br />

during the first six weeks after surgery<br />

and then begins to slowly strengthen. At<br />

the six-month mark, the graft returns to<br />

about 50 percent of its original strength. It<br />

continues to strengthen for one to two<br />

years, while it is “vascularized” and incorporated<br />

by the knee (fig. 2).<br />

If a brace can reduce strain on the<br />

reconstructed ACL, is it possible that it<br />

Figure 1 ACL Strain Produced by Anterior Tibial Loading (After Beynnon et al. 1995)<br />

Figure 2 ACL Graft After Surgery (After Blickenstaff et al. 1977)<br />

100<br />

100<br />

80<br />

80<br />

60<br />

60<br />

40<br />

40<br />

20<br />

20<br />

0<br />

12 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 36<br />

0<br />

Weeks<br />

3<br />

after<br />

6<br />

surgery<br />

9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 36<br />

Weeks after surgery<br />

Graft strength (%) (%)<br />

20 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

d a clear difference indicating that bracing increased knee stability.<br />

may also protect the native ACL?<br />

Unfortunately, that question has not been<br />

directly studied among skiers as it has<br />

been among college football players.<br />

While there really isn’t enough data to say<br />

for sure, my own experience would suggest<br />

that it’s likely.<br />

So we are left with many more questions<br />

than answers. What we do know is<br />

that 1) ACL tears are extremely common<br />

among many professional athletes and<br />

weekend warriors, especially skiers; 2)<br />

ACL reconstruction is a highly effective<br />

but painful intervention with a 16-week<br />

or longer rehabilitation period; 3) temporary<br />

ACL bracing is generally recommended<br />

after surgery to protect the graft<br />

during its most vulnerable phase; 4)<br />

reconstructed ACLs can be re-ruptured;<br />

and 5) there is solid experimental evidence<br />

that bracing reduces strain on the<br />

ACL graft during the healing process.<br />

What we don’t know for sure is<br />

whether bracing will reduce the risk of rerupturing<br />

the ACL or even prevent ACL<br />

tears in the first place or well after rehab.<br />

One brace manufacturer, DonJoy, is so<br />

confident that its top-of-the-line brace<br />

can prevent re-rupture of the ACL that<br />

the company says it will actually pay a<br />

portion of the bill if you re-rupture the<br />

ACL graft while wearing the brace.<br />

Clearly we need more data to answer<br />

this central question. In the interim, as I<br />

continue to recover from what my wife<br />

insists had better be my last ACL reconstruction,<br />

I’m left to ponder the fate of my<br />

brace. Certainly, being able to pass the<br />

PSIA Level III exam without an ACL and<br />

while braced has endeared the device to<br />

me. I feel a subjective sense of support<br />

and security when I wear it, and studies<br />

would indicate that I also experience an<br />

objective increase in support. What little I<br />

lose in range of motion because of the<br />

brace I more than make up for knowing<br />

that the strain on the knee is relieved<br />

while wearing it. Without the brace, I<br />

would not have been able to ski at all.<br />

For Eric Schlopy, even the slight<br />

weight, drag, and movement restriction<br />

of a brace can mean the difference<br />

between winning and losing. But I’m not<br />

Eric Schlopy. I want to ski and ski well,<br />

but I hardly notice drawbacks from the<br />

brace. What I do notice is my increased<br />

sense of stability and confidence. I might<br />

be weak-kneed, but I’m no wimp, and I’m<br />

not ready to succumb just yet. ✚<br />

References<br />

Boughton, B. “Prophylactic: Football Linemen<br />

Experience the Greatest Benefit.” The<br />

Magazine of Body Movement and Medicine<br />

June 2000: 21–25.<br />

Nemeth, G. et al. “Electromyographic Activity in<br />

Expert Downhill <strong>Ski</strong>ers Using Functional<br />

Knee Braces After Anterior Cruciate Ligament<br />

Injuries.” The American Journal of Sports<br />

Medicine 25, no. 5 (1997): 635–641.<br />

Beynnon, B.D. et al. “The Effect of Functional Knee<br />

Bracing on the Anterior Cruciate Ligament in<br />

the Weightbearing and Non-weightbearing<br />

Knee.” The American Journal of Sports<br />

Medicine 25, no. 3 (1997): 353–359.<br />

Beynnon, B.D. et al. “An In-vivo Investigation of<br />

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Strain: The Effect<br />

of Functional Knee Bracing and Attachment<br />

Strap Tension.” Paper presented at the annual<br />

meeting of the Orthopedic Research Society,<br />

Orlando, FL.<br />

Blickenstaff, K.R. et al. “Analysis of a Semitendinosus<br />

Autograph in a Rabbit Model.”<br />

American Journal of Sports Medicine 25, no. 4<br />

(1997): 554–559.<br />

Dr. Michael Patmas is the medical director of<br />

the Providence Ambulatory Care and Education<br />

Center in Portland, Oregon. He is a PSIA-certified<br />

Level III alpine ski instructor at Mount Hood<br />

Meadows, Oregon.<br />

W inte r 2005 | <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine 21

NUTRITION<br />

on the Slopes<br />

solutions for the fast food blues<br />

BY ROBIN PEGLOW<br />

Have you ever found yourself choking down an $8 burger, gnawing through a slightly<br />

frozen, less-than-tasty protein bar, or skipping meals altogether only to collapse into a<br />

useless, exhausted pile at the end of your shift? Amid the pressures and quick pace of<br />

patrolling the slopes and tending to skiers and snowboarders, proper nutrition is often the first<br />

thing that falls by the wayside.<br />

But the trade-off might be worse than you imagine. A lack of sustenance can definitely spoil<br />

more than your day; it can adversely affect your response time, your decision making, and even<br />

your ability to empathize with your patients.<br />

As a holistic health counselor, I spend my days talking to<br />

people about how nutrition can either enhance your<br />

daily experience or detract from it. Getting the nutrients<br />

you need doesn’t have to be a challenge, and this article<br />

explains how even the busiest among us can sustain the energy<br />

required to get through the day without fading and fizzling<br />

before noon or a couple hours after lunch.<br />

The key to good eating, as you might have guessed, is moderation.<br />

If you really love fries, go ahead and eat them on occasion.<br />

Have a burger now and then. But whatever you do, don’t<br />

rely on these things for nutrition.<br />

What then, you ask, should I eat? It doesn’t have to be complicated,<br />

and it is essentially a matter of getting back to the<br />

basics. “The basics” is shorthand for whole grains, fruits, vegetables,<br />

legumes (i.e., beans, lentils, and nuts), and healthy proteins<br />

such as tofu, salmon or tuna, and antibiotic- and hormone-free<br />

meats. Due to the nature of my training in nutrition I recommend<br />

choosing organic vegetables and “clean” meats or proteins.<br />

While scientists may argue over the benefits of organic and<br />

unmodified foods, I suggest them because I believe natural fuel<br />

burns cleaner than fuel that contains “additives.”<br />

I also tell people to try to stay away from obviously sugary or<br />

processed foods on the hill mainly because they tend to sap your<br />

energy rather than add to it. Eating healthy should give you the<br />

power you need when duty calls.<br />

MOM KNEW BEST<br />

Aside from the substantial financial toll that on-mountain<br />

“convenience food” can have on your wallet, you’d be wise<br />

to consider pizza or a burger and fries as a bad nutritional<br />

transaction as well. Such items provide little benefit for<br />

your body in terms of quality energy. You may crave fat to satisfy<br />

a raging hunger, but consuming greasy foods like these will leave<br />

you devoid of valuable nutrients. And, no, just taking a vitamin<br />

tablet or eating half a dozen protein bars isn’t the answer either.<br />

Your body functions best when it gets its nutrients from fresh<br />

sources. That’s right, your mom wasn’t just perpetuating some<br />

myth by telling you that eating fruits and vegetables would make<br />

you grow healthy and strong.<br />

Eating right is about far more than simply putting calories<br />

down the hatch, and the purpose of consuming nutrient-rich<br />

foods is that they provide energy for the vital functions that<br />

occur within your body on an ongoing basis. For example, the B<br />

vitamins found in foods such as black beans, meat, eggs, nuts,<br />

and dairy products support energy production, nervous system<br />

function, stress responses, and muscle tone. The folic acid you<br />

24 <strong>Ski</strong> <strong>Patrol</strong> Magazine | Winter 2005

get from barley, brown rice, dates, and salmon helps with energy<br />

production and protects you against sunburn and skin cancer.<br />

The vitamin A you assimilate by eating asparagus, sweet potatoes,<br />

cantaloupe, and beet greens supports vision and prevents<br />

fatigue. The vitamin C you get from an orange or a helping of<br />

broccoli will aid tissue repair, improve adrenal gland function,<br />

and enhance your immune system. And these are just a few of<br />

the nutrients your body needs to function properly! Only a small<br />

amount of your daily requirements of each of these nutrients are<br />

provided by fries, soda, or even protein shakes and energy bars.<br />

Basic nutritive needs aside, the combination of intense exercise,<br />

long work hours, and stress that is part and parcel of<br />

patrolling means that you probably need to take in more than the<br />

recommended daily allowance of vitamins and minerals. In her<br />

book, Your Body Knows Best, nutritionist Ann Louise Gittleman<br />

points out that stress alone can act as a nutrient-vampire that<br />

leaches precious magnesium, calcium, zinc, potassium, sodium,<br />

and copper from the body’s tissues.<br />

Living off junk food just won’t cut it. Nutrients are essential<br />

if you want to be your best.<br />

THE MOST IMPORTANT<br />

MEAL<br />

Your mom was right about something<br />

else: You need a good breakfast<br />

every day. <strong>Ski</strong>pping your morning<br />

meal is a giant mistake. Not only does your<br />

metabolism function 25 percent better<br />

when you eat within 1 hour of waking,<br />

your body simply needs the fuel.<br />

For example, let’s say you go home at<br />

night, have dinner at 7 p.m., and then don’t<br />

eat until lunch at noon the next day. You’ve<br />

been without food, essentially “fasting,” for<br />

17 hours! That’s a surefire recipe for disrupting your metabolism<br />

and blood glucose levels. Your body uses glucose, a simple<br />

sugar, throughout the day to provide you with energy, but a<br />

blood-sugar imbalance can turn your thinking “foggy” and<br />

leave you feeling sleepy, weak, or irritable. These are all signs<br />

that you’re running on empty.<br />

Therefore, when you roll out of bed, give your body fiber,<br />

protein, and nutrients pronto. If you’re one of those people who<br />

wake up and say, “I’m just not hungry,” you have to train your<br />

brain and body to think differently in the morning. The best way<br />

to get into the habit of having breakfast is to start small in terms<br />

of adding a new dietary ritual.<br />

Chances are that the first item I’m going to recommend for<br />

your morning menu is something you used to have as a kid: Hot<br />

cereal was good for you then and it’s great for you now.<br />

Oatmeal, the old standby, is still popular with many athletes,<br />

and I’d recommend steel-cut or regular oats even though they<br />

<strong>Ski</strong>pping your morning meal<br />

is a giant mistake. Not only<br />

does your metabolism function<br />

25 percent better when you<br />

eat within 1 hour of<br />

waking, your body simply<br />

needs the fuel.<br />

take longer to prepare than the “instant” kind. (Instant packaged<br />

oatmeal is stripped of nutrients to speed up the cooking time.)<br />

Another excellent choice is a seven- or eight-grain cooked<br />

cereal, and there are a number of these whole-grain combinations<br />

for sale in the natural food aisles of most grocery stores<br />

nowadays. Whole-grain hot cereals are filling, hearty, and will<br />

provide you with fuel well into late morning.<br />

If you’re concerned about the extra time it takes to cook hot<br />

cereal, you can prepare it the night before and briefly reheat it<br />

before you run out the door or eat it cold on the road. Filled with<br />

fiber, protein, essential fatty acids (the “good fats”), and B vitamins,<br />

oatmeal and whole-grain cereals can provide a great beginning<br />

to your day. Throw in a sliced banana for potassium and<br />

some almonds for protein, and you’ve got one winner of a complete<br />

morning meal.<br />

If you’re a devotee of eggs and toast in the morning, that’s okay<br />

too. Just make sure that you use whole-grain bread for the toast,<br />

and when it comes to cooking the eggs be sure to cook them with<br />

little or no oil in a nonstick skillet. Really, folks, the yolks are not the<br />

fat culprit for clogged arteries; instead, it’s<br />

the hydrogenated fat in your Danish or the<br />

margarine you’re using on your toast that’s<br />

the problem. (For more on hydrogenation,<br />

check out the entry titled “Overconsumption<br />

of Processed Foods” in the “Top<br />

Ten Nutrition Mistakes” sidebar on page<br />

26.) Of course, moderation is also important<br />

in terms of the fats you consume with<br />

poultry, dairy, or meat. Although people<br />

have short-term success with high<br />

protein/low carb diets, these regimens aren’t<br />

necessarily well-balanced and eventually can<br />

lead to problems in the long run. A good<br />

rule of thumb is to have several meals each<br />

week that incorporate protein from vegetable sources (e.g., from<br />

soy or nuts) or fish rather than three daily doses of animal protein.<br />

When it comes to the nutritional value of toast, whole-grain<br />

bread is the gold standard. Whole-grain breads (and whole<br />

wheat tortillas) contain vitamins, fiber, and essential fatty acids.<br />