FSLG Annual Review - Senate House Libraries - University of London

FSLG Annual Review - Senate House Libraries - University of London

FSLG Annual Review - Senate House Libraries - University of London

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

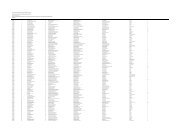

Compilation <strong>of</strong> the Bibliography<br />

Mylne is best remembered for two works: The eighteenth-century French novel:<br />

techniques <strong>of</strong> illusion (1965) and for the work on which she collaborated with Angus<br />

Martin and Richard Frautschi Bibliographie du genre romanesque français, 1751-<br />

1800 (1977). It would seem that the compilation <strong>of</strong> the latter went hand-in-hand<br />

with the building up <strong>of</strong> the collection now known as the Mylne Collection. The<br />

Bibliographie du genre romanesque français, 1751-1800 follows on from an earlier<br />

bibliography by Silas P. Jones which covers the first half <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century,<br />

entitled A list <strong>of</strong> French prose fiction from 1700 to 1750: with a brief introduction by<br />

S. Paul Jones (1939). Jones’s bibliography was however only to bear fruit in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

critical output several decades later in the 1960s and 1970s. Creative stagnation was<br />

thought to have set in with the French novel in the second half <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth<br />

century. Vivienne Mylne was not convinced by this view. She was sure that the<br />

originality and special character <strong>of</strong> the French novel during this period <strong>of</strong> sensibility,<br />

combined with its interest in moral questions, would be revealed if the totality <strong>of</strong><br />

this literature was better known. This provided a motivation for the compilation <strong>of</strong><br />

the bibliography.<br />

The definition <strong>of</strong> ‘genre romanesque’ is wider than that <strong>of</strong> a mere novel. Contes for<br />

instance, or indeed anything with a narrative element (unless in verse) were<br />

included. As the 18 th century advanced, translations grew in number and so they too<br />

were included in this bibliography <strong>of</strong> the second half <strong>of</strong> the 18 th century. Unlike<br />

Jones, the trio attempted to enumerate all editions <strong>of</strong> a particular work and unlike<br />

Jones they also included brief information about the content <strong>of</strong> each work. The main<br />

libraries used were the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale and the<br />

Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, although they also made use <strong>of</strong> the volumes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

National Union Catalog which started to issue its printed volumes after they had<br />

commenced work. As these volumes began to appear in 1968 and their project was<br />

well under way by this time we can infer that the three <strong>of</strong> them began work on the<br />

bibliography in the mid-sixties which would have been just after Vivienne Mylne<br />

completed her book on the eighteenth-century French novel. They also made use <strong>of</strong><br />

what Vivienne Mylne terms ‘auxiliary libraries’ including those <strong>of</strong> Leningrad and<br />

Moscow and the Chateau d’Oron in Switzerland (invaluable for novels in the latter<br />

years <strong>of</strong> the 18 th century).<br />

The achievement <strong>of</strong> this bibliography is all the more remarkable when one considers<br />

that the three <strong>of</strong> them were living on different continents – Angus Martin in<br />

Australia (Macquarie <strong>University</strong>), Richard Frautschi in the USA (Pennsylvania State<br />

<strong>University</strong>) and Vivienne Mylne in the UK, before the advent <strong>of</strong> email and OCLC<br />

FirstSearch and computers in general. One stumbling-block mentioned in the<br />

extensive introduction to the bibliography was that the French revolutionary<br />

calendar does not neatly fit with the Gregorian calendar as its year begins and ends<br />

with the month <strong>of</strong> Vendémiaire which begins on 22, 23 or 24 September. As one<br />

rarely knows in which month a book is published, they decided to adopt the arbitrary<br />

but necessary expedient <strong>of</strong> nominating the Gregorian year which had the most<br />

months in common with the revolutionary one – thus Year 1 became 1793, Year 2<br />

1794 and so on.<br />

27