PEDIATRICIAN Spring 2003 - AAP-CA

PEDIATRICIAN Spring 2003 - AAP-CA

PEDIATRICIAN Spring 2003 - AAP-CA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

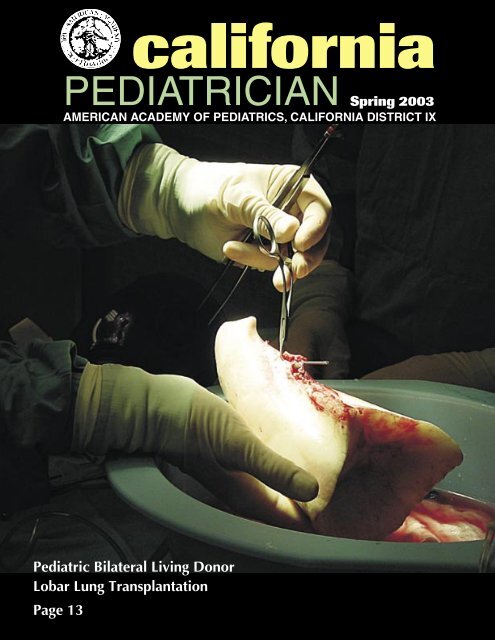

california<br />

<strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong><br />

AMERI<strong>CA</strong>N A<strong>CA</strong>DEMY OF PEDIATRICS, <strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA DISTRICT IX<br />

Pediatric Bilateral Living Donor<br />

Lobar Lung Transplantation<br />

Page 13

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF<br />

Jeffrey S. Penso, M.D.<br />

9696 Culver Blvd., #108<br />

Culver City, <strong>CA</strong> 90232<br />

(310) 204-6897<br />

jpenso@ucla.edu<br />

ASSISTANT EDITOR<br />

Marianne Hockenberry<br />

aapmarianne@aol.com<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

Stuart A. Cohen, M.D.<br />

6699 Alvarado Rd., #2200<br />

San Diego, <strong>CA</strong> 92120<br />

(619) 265-3400<br />

scohen98@ipninet.com<br />

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION<br />

Rosalie Blazej<br />

50 Laidley St.<br />

San Francisco, <strong>CA</strong> 94131<br />

(415) 695-0264 FAX (415) 641-5409<br />

rblazej@pacbell.net<br />

DISTRICT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR<br />

Kris Calvin, MA<br />

853 Ramona Ave.<br />

Albany, <strong>CA</strong> 94706<br />

(510) 559-8383 FAX (510) 559-8464<br />

aapcalifornia@aol.com<br />

Marianne Hockenberry<br />

Associate Director<br />

EDITORIAL BOARD<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Lewis Nerenberg, M.D.<br />

Chapter 2<br />

Joan E. Hodgman, M.D.<br />

Chapter 3<br />

Howard Taras, M.D.<br />

Chapter 4<br />

Stanley Galant, M.D.<br />

CHAPTER OFFICES<br />

Chapter 1 Executive Director<br />

Beverly Busher<br />

900 Fifth Ave. #204<br />

San Rafael, <strong>CA</strong> 94901<br />

(415) 459-4775<br />

aapbev@aol.com<br />

www.aapca1.org<br />

Chapter 2 Executive Director<br />

Kathleen Shematek, MPH<br />

6233 East Allison Circle<br />

Orange, <strong>CA</strong> 92869<br />

(714) 744-8245<br />

aapca2kshematek@socal.rr.com<br />

www.aapca2.org<br />

Chapter 2 Chapter Administrator<br />

Eve Black<br />

P.O. Box 2134<br />

Inglewood, <strong>CA</strong> 90305<br />

(323) 757-1198<br />

aapcach2@aol.com<br />

Chapter 3 Executive Director<br />

Erika Kalter<br />

3020 Children’s Way<br />

MC 5073<br />

San Diego, <strong>CA</strong> 92123<br />

(858) 569-8816<br />

sdpeds@chsd.org<br />

www.aapca3.org<br />

Chapter 4 Executive Director<br />

Debbie Monfea<br />

12377 Lewis Street, #103<br />

Garden Grove, <strong>CA</strong> 92840<br />

(714) 971-0695<br />

ca4aap@sbcglobal.net<br />

www.aapca4.org<br />

Address comments and questions to<br />

Jeffrey S. Penso, M.D.<br />

jpenso@ucla.edu<br />

2 District Report<br />

Burton Willis, M.D. and Kris Calvin, M.A.<br />

3 Childhood Cancer Survivors Report Life Changes<br />

Brad J. Zebrack, Ph.D., M.S.W., and Mark A. Chesler, Ph.D.<br />

Today 75% of children diagnosed with various forms of cancer in the<br />

United States are expected to survive their disease and treatment. But<br />

what of their quality of life expected, enjoyed, or endured?<br />

4 Tandem Mass Spectrometry in Newborn Screening<br />

George C. Cunningham, M.D., M.P.H.<br />

The Department of Health Services keeps us current on neonatal<br />

screening.<br />

5 Culturally Appropriate Communication Is<br />

Good Medical Practice<br />

Allan Lieberthal, M.D., F<strong>AAP</strong><br />

Poor communication results in inferior medical care, and is not in<br />

compliance with federal government standards. Can we improve<br />

compliance?<br />

6 CMA House of Delegates Report<br />

Paul Y. Qaqundah, M.D.<br />

State budget concerns were key but access to the care and employer<br />

mandate proposals were issues we wrestled with in San Francisco.<br />

7 Weighing the Radiation Risks of CT Scans<br />

Nikta Forghani, M.D., Ronald A. Cohen, M.D., Myles B. Abbott,<br />

M.D.<br />

CT scans expose children to high doses of ionizing radiation. What<br />

are the best ways to use CT scans?<br />

8 Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis<br />

Robert M. Bernstein, M.D.<br />

What is the natural history of scoliosis, which cases need to be<br />

referred? What are the treatment options?<br />

9 Preventing Ear Infections in Children<br />

Harry Pellman, M.D.<br />

AOM is the most common bacterial infection diagnosed in children.<br />

What is known to reduce the frequency of middle ear problems?<br />

10 A Low-Glycemic Index Diet in the<br />

Treatment of Pediatric Obesity<br />

David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD, et. al.<br />

Obesity is arguably the most prevalent medical problem in the<br />

United States today. Weight loss on current reduced-fat diets is<br />

characteristically modest and transient. Can a novel treatment, the<br />

low-glycemic index diet, be the breakthrough we need?<br />

12 Why California’s MICRA Is Good for the Nation<br />

Ron Bangasser, M.D.<br />

We face a national medical liability crisis. The solution is California’s<br />

MICRA.<br />

13 Ten-Year Experience with Pediatric<br />

Bilateral Living Donor Lobar Lung Transplantation<br />

Marlyn S. Woo, M.D. and Vaughn A. Starnes, M.D.<br />

The medical team had exhausted all conventional medical and surgical<br />

options. What about lung transplantation for this dying patient?<br />

14 The Tao of Pediatrics and Chinese Medicine<br />

Wendy Yu, M.S., L.Ac., Jeffrey I. Gold, Ph.D.,<br />

Michael H. Joseph, M.D.<br />

Health is not just about a disease factor, it’s about the whole<br />

environment.<br />

17 In Memoriam — Joseph H. Davis<br />

A beloved pediatrician is recalled by his son.<br />

18 Chronic Pain in Children: A Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial<br />

Treatment Approach (Part III)<br />

Michael H. Joseph, M.D. and Jeffrey I. Gold, Ph.D.<br />

we must decrease all ongoing nociceptive pain and support,<br />

encourage, and reinforce the child in working through chronic pain<br />

symptomatology.<br />

21 Twenty-Five-Years of Home Mechanical Ventilation in Children:<br />

The Program at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles<br />

Manisha Witmans, M.D., Sheila S. Kun, R.N., M.S., and<br />

Thomas G. Keens, M.D.<br />

The last 25 years has witnessed enormous improvement in home<br />

mechanical ventilation. Since the inception of the home ventilator<br />

program in 1977, the program at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles<br />

CHLA has grown to include over 375 children.<br />

CONTENTS<br />

<strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>/ 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS continued<br />

District Report<br />

<strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> Advocacy in Hard Times:<br />

Multiple Strategies to Success<br />

Burton Willis, M.D. and Kris Calvin, M.A.<br />

Despite the flowering trees around the majestic Capitol dome, Sacramento<br />

offers few pretty pictures this year. Take a shot of the full landscape: an<br />

unprecedented $30 billion dollar-plus state deficit looms. Zoom in for a<br />

family portrait? Democrats, Republicans and the Governor’s office seem trapped on<br />

their own limited platforms, with no real solution in sight. Worse yet for pediatrics,<br />

snapshot photos of the health budget show only shrinking dollar signs. This is because<br />

health dollars are largely unprotected in an era of budget “lock-ins” in other areas due<br />

to initiatives or other mandates.<br />

The California District of the American Academy of Pediatrics (<strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong>), representing<br />

all four California <strong>AAP</strong> Chapters, has developed a pragmatic, yet hopeful<br />

approach to this state crisis. Strategies include:<br />

• Increased <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> leadership and participation in coalitions to ensure that<br />

children’s health advocates are heard above the din in the budget debates in<br />

Sacramento. This includes intense advocacy with 70 other groups to oppose<br />

proposed cuts to Medi-Cal physician reimbursment.<br />

• Build on successes. Last year <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> and our allies were successful in saving<br />

and expanding the Child Health and Disability Prevention (CHDP) state-only<br />

program. If state-only CHDP had been eliminated these children would have<br />

fallen into the ranks of the uninsured and an important source of pediatric revenue<br />

to sustain their care would have been eliminated. This year <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> has<br />

worked closely with the state to protect the program and improve it. Starting<br />

July 1, <strong>2003</strong> CHDP providers will be able to pre-enroll children into the Medi-<br />

Cal program through the Internet or new Point of Service devices. For more<br />

information go to www.medi-cal.ca.gov/new_chdp.asp.<br />

• “Back-end” involvement in implementation of children’s programs. Programs<br />

are best protected in the budget if they are fully implemented and working well<br />

for both physicians and children. For example, <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> “Chapter Champions”<br />

are working with the state to ensure that the already enacted Newborn Hearing<br />

Screening Program is fully implemented with appropriate reimbursement.<br />

• Prevent budget problems before they start. This includes careful legislative monitoring<br />

and intervention to ensure that only those bills whose benefits outweigh<br />

their costs are enacted. This requires <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> to be available to legislators and<br />

their staff as an expert resource on a wide range of issues, including vision<br />

screening, early brain development anticipatory guidance and HMO contracting<br />

issues. We have already had great success this year in this regard.<br />

• Engage legislators and policymakers by utilizing credible pediatrician advocates.<br />

Legislators and other policymakers prefer to hear from you, practicing<br />

pediatricians with first-hand experience with children and families, rather than<br />

from lobbyists and staff. Something as simple as a “form” letter from you to<br />

your legislator on a priority <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> issue matters. Those of you with a flair for<br />

public comment can make a tremendous difference by testifying for <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong><br />

on a bill or budget item in Sacramento. Building an ongoing trust relationship<br />

with your local legislator in his or her home office is invaluable. If you have<br />

not already completed the brief <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> Grass Roots Advocacy Survey please<br />

request one from aapcalifornia@aol.com.<br />

Improving the state child health picture in California this year will take more<br />

than just a pretty new frame. <strong>AAP</strong>-<strong>CA</strong> will continue to work towards real change for<br />

pediatricians and the children and families that you serve.<br />

22 Childcare Health Linkages Program: How<br />

Pediatricians Can Collaborate with Local<br />

Childcare Health Consultants<br />

Robin Calo, R.N., M.S., P.N.P. and<br />

Karen Sokal-Gutierrez, M.D., M.P.H.<br />

When you think about the young children in your<br />

practice, who besides their parents takes care of<br />

them? Is a childcare consultant coming to your<br />

neighborhood?<br />

23 Eve Black Honored<br />

24 Annual Las Vegas Seminars —<br />

25 Years of District Education and Support<br />

Rosalie Blazej and Milton Arnold, M.D.<br />

For 25 years, pediatricians have flocked to Las Vegas<br />

to learn and relax.<br />

25 Selling Tobacco Products as a<br />

Public Health Issue<br />

Trisha Roth, M.D.<br />

At the urging of the California Medical Association<br />

and with the help of the Preventing Tobacco Addiction<br />

Foundation, a proposal is on the table to increase the<br />

minimum age for purchasing tobacco to 21.<br />

26 Early Hearing Detection and Intervention<br />

Sudeep Kukreja, M.D.<br />

To be successful, California needs to address several<br />

issues in the Newborn Hearing Screening Program.<br />

29 SED — California Region<br />

Leonard Kutnik, M.D.<br />

One in 10 children suffer from a mental health<br />

illness but only one in five children receive specialty<br />

services. Unfortunately, even this rate of treatment is<br />

not achieved in the Healthy Families Program.<br />

29 California Surgeon General Needed to<br />

Protect Californians<br />

31 Retirement Options for Pediatricians<br />

Joan E. Hodgman, M.D.<br />

Retirement should not be dull or boring. With the<br />

increase in the average life expectancy, more and<br />

more of us can look forward to years of active life<br />

after retirement.<br />

32 Last Word: After the Iraq War<br />

Jeffrey S. Penso, M.D.<br />

Even with victory an implacable worldwide enemy<br />

will remain. While physicians are aware of the<br />

continued threat of bioterrorism, we have yet to<br />

recognize that bioterror will change relationships<br />

between physicians and the community.<br />

33 President-Elect Candidates<br />

33 Contributors<br />

35 Officers and Committees<br />

California Pedatrician does not<br />

assume responsibility for authors’<br />

statements or opinions. Opinions<br />

expressed are not necessarily those<br />

of California Pediatrician or the California<br />

District, American Academy<br />

of Pediatrics.<br />

Vol. 19 No. 1 <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong><br />

California Pediatrician [ISSN 0882-3421] is<br />

the official publication of the American Academy<br />

of Pediatrics, California District IX.<br />

Copyright © <strong>2003</strong> American Academy of<br />

Pediatrics, California District IX<br />

2 / <strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>

Childhood Cancer Survivors Report Life Changes<br />

Brad J. Zebrack, Ph.D., M.S.W., and Mark A. Chesler, Ph.D.<br />

“I used to get really depressed<br />

on the anniversary when I got<br />

sick, August 4. I used to get really<br />

upset; I even wore black to work.<br />

You know, this is the day my life<br />

changed... Like this is really weird,<br />

I see a grave, and that’s the person<br />

that died, on August 4, 1985. She’s<br />

gone. Because you know, my life<br />

had to change, I had cancer and<br />

I can’t go back there, I can’t go in<br />

the past, so it’s like, she’s gone.<br />

(24-year old survivor of childhood<br />

cancer).”<br />

Prior to the 1970s and the advent and use of<br />

multi-modal chemotherapy, survival rates<br />

for children diagnosed with leukemia and<br />

other forms of cancer were dismal. Today,<br />

advances in treatment and the coordination of<br />

pediatric treatment through clinical trials have<br />

greatly increased the long-term life chances<br />

of these young people. Indeed, recent reports<br />

indicate that 75% of children diagnosed with<br />

various forms of cancer in the United States<br />

are expected to survive their disease and treatment.<br />

As we witness increasing lengths of survival<br />

for individuals diagnosed with cancer as<br />

children and a growing number of long-term<br />

survivors there is no indication of their quality<br />

of life expected, enjoyed, or endured. In<br />

1998, the American Cancer Society Task Force<br />

on Children and Cancer reported that “(T)he<br />

progress achieved in attaining 80% survival<br />

among children and adolescents and young<br />

adults with cancer can be justified only if their<br />

physical, emotional, and social quality of life<br />

also are protected.” Thus, success in pediatric<br />

oncology requires researchers and health care<br />

professionals to attend to the psychosocial and<br />

behavioral consequences of treatment and to<br />

the quality of life of these survivors.<br />

Cancer Survivorship<br />

Research literature on cancer survivors consistently<br />

refers to the notion that experiencing<br />

cancer can lead to changes in people’s lives.<br />

While many studies of cancer survivors document<br />

long-term sequelae as having deleterious<br />

effects on psychological well-being and social<br />

functioning, relatively few have investigated<br />

positive adaptation and factors associated with<br />

the potentials for positive life changes which<br />

survivors attribute to cancer.<br />

People often report that they have made<br />

positive changes in themselves and their lives<br />

after a negative event or trauma. Several scholars<br />

have described such changes as part of a<br />

process of cognitive reappraisal in the face<br />

of, or aftermath of, trauma. People thus may<br />

reframe or reinterpret their illness experience<br />

or themselves (e.g., from “victim to victor”),<br />

making new meaning out of their situation.<br />

Seminal work by Taylor indicated that a sizable<br />

proportion of women experienced positive<br />

life changes following their experiences<br />

with breast cancer. Similarly, in a comparison<br />

of adult bone marrow transplant patients to<br />

a matched control group without a history<br />

of cancer, the patients equaled or exceeded<br />

controls in the likelihood of reporting positive<br />

psychosocial changes in life.<br />

Some investigators, however, caution<br />

against such interpretations in that reports of<br />

positive outcomes may be “illusions,” “repressive<br />

denial,” or self-serving distortions that are<br />

more typical of poor mental health rather than<br />

positive adaptation. Our own view, based on<br />

empirical work as well as on our own personal<br />

and clinical experiences, is that cancer and<br />

other trauma should not be viewed as a stressor<br />

with uniformly negative outcomes but rather as<br />

transitional events that create the potential for<br />

both positive and negative change.<br />

Life changes for survivors of<br />

childhood cancer<br />

These issues are beginning to surface in<br />

recent research with survivors of childhood<br />

cancer. There is general agreement that many<br />

adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood<br />

cancer have lasting physical deficits and<br />

that some experience negative psychological<br />

changes as a result of their illness. At the same<br />

time, several scholars argue from empirical<br />

findings that demonstrate that a sizable portion<br />

of this population is coping more positively<br />

than their peers and that they have changed<br />

their psychologic orientations and outlooks<br />

for the better. These positive outcomes are not<br />

necessarily unrealistic or naïve “halo effects”<br />

because often they are accompanied simultaneously<br />

by details of how cancer has had deleterious<br />

effects. Furthermore, these results mirror<br />

findings and interpretations reported in the<br />

literature about gains in “secondary benefits”<br />

such as enhanced relationships with family<br />

members, emotional maturity, and greater life<br />

appreciation.<br />

Young adult survivors’ own words illuminate<br />

the changes they attribute to having had<br />

cancer as children.<br />

“I feel I’ve learned good lessons<br />

from it (my cancer). I realize what’s<br />

important in life and I don’t take<br />

everything for granted. I want to<br />

live life to the fullest.”<br />

“I think I’m stronger. I am very<br />

independent now. I set my mind<br />

to doing something and I do it. I<br />

think a part of me has definitely<br />

been impacted by the fact that<br />

I’ve had cancer. There are a lot<br />

of go-getters out there, but when<br />

you’ve accomplished something<br />

like surviving the cancer and<br />

treatments, when you’ve gotten<br />

through something like that, it just<br />

gives you a determination, a drive,<br />

to achieve well in school and to do<br />

well in life.”<br />

In addition, many long-term survivors of<br />

pediatric malignancies indicate that there is<br />

something inherent to the cancer experience<br />

that makes dealing with the “normal” challenges<br />

of every day life different from a life<br />

without cancer.<br />

“You know, it’s definitely a huge<br />

adjustment getting married, and<br />

having a child, so that’s adjustment<br />

<strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>/ 3

in and of itself, but I think you<br />

throw a whole other element in<br />

that, you know, like going through<br />

what I went through [cancer],<br />

and you need to try to fit that in<br />

somewhere. And you don’t know<br />

where it fits.”<br />

These statements above are consistent<br />

with what Tedeschi & Calhoun refer to as<br />

“philosophical outcomes” or “new priorities”<br />

in life. They reflect an internal process of<br />

“meaning making,” whereby many of these<br />

survivors (with help from external supports,<br />

no doubt) have reframed or reinterpreted their<br />

initial trauma, placed their current worries or<br />

negative effects in context, and made new and<br />

positive meaning out of their cancer experience.<br />

Complementing recent concern about<br />

evidence of a “post-traumatic stress syndrome”<br />

among childhood cancer survivors, some<br />

survivors may experience “post-traumatic<br />

growth” or a sense of “thriving.” The need for<br />

further research on these issues, and resultant<br />

estimates of the proportion of the childhood<br />

cancer survivor population falling into either<br />

category, is vital.<br />

Implications for intervention<br />

Evaluating reports of positive change and<br />

enhanced quality of life associated with cancer<br />

is important for two reasons: (1) it challenges<br />

us to try to understand the reality and validity<br />

of such reports; and (2) it suggests the need<br />

for psychosocial interventions that not only<br />

prevent or alleviate negative sequelae but also<br />

promote positive outcomes and increase longterm<br />

survivors’ opportunities for expressing<br />

and experiencing cancer as a potentially transformative<br />

experience. Such interventions may<br />

start with the subtle positive messages often<br />

presented at diagnosis (“you will survive this<br />

illness”), then subsesquently include the mobilization<br />

of family and friends’ supports, and<br />

skilled peer (“let me tell you what I learned”)<br />

or professional counseling.<br />

In the current context, where medical<br />

survival from childhood cancer is no longer a<br />

singular or rare phenomenon, the possibilities<br />

of full psychological survival and even growth<br />

have enormous theoretical and practical implications.<br />

The long term impact of experiencing<br />

or recognizing positive change is yet to be fully<br />

explored, but theoretically it has additional<br />

implications for the construction, or re-construction,<br />

of personal and social identity for<br />

adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.<br />

Tandem Mass Spectrometry in<br />

Newborn Screening<br />

George C. Cunningham, M.D., M.P.H.<br />

The state is currently conducting a legislatively mandated demonstration project to<br />

evaluate the most efficient way to add the Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS)<br />

technology to our newborn screening for metabolic disease. This technology measures<br />

47 different analytes in a blood specimen and can detect over 25 different disorders.<br />

This report is to inform pediatricians generally about the progress and future of this proposed<br />

expansion. Since starting in January 2002, 221,913 newborns have participated in this voluntary<br />

MS/MS screening. The Genetic Disease Branch classified 349 as initially positive and<br />

referred them to metabolic centers for diagnostic evaluation, leading to a definite diagnosis<br />

in 33 newborns. Participation in the pilot is only being offered in 60% of maternity hospitals,<br />

but is accepted by 90% of the mothers when offered. The initial referred rate at this time is<br />

about 8 of every 10,000 newborns screened and approximately 1 in 10 of the referred newborns<br />

have a disorder. The disorders are serious and with a few exceptions can be prevented<br />

or ameliorated by treatment. (See Chart)<br />

The project has demonstrated that the cost of case detection will be $60 to $80,000 per<br />

case, which is offset by the benefits of lives saved and costly hospitalization for treatment<br />

averted. We appreciate the cooperation received from pediatricians in making this project a<br />

success. There are 24 states that are implementing or using MS/MS to expand their programs<br />

at this time. Unfortunately, there are no funds in the current budget to continue this project and<br />

unless funds are added during the budget process, the project will terminate in June <strong>2003</strong>.<br />

Category Description Example Number<br />

Diagnosed<br />

Amino Acid<br />

Disorders<br />

Organic Acid<br />

Disorders<br />

Fatty Acid<br />

Oxidation<br />

Disorders<br />

Caused by the<br />

accumulation of<br />

amino acids in the<br />

blood (e.g. arginine)<br />

Caused by the toxic<br />

buildup of organic<br />

acids in the blood<br />

(e.g., proprionic acid<br />

or methylmalonic<br />

acid).<br />

Caused by a defect<br />

in the conversion of<br />

fats into fatty acids<br />

for use as an energy<br />

source<br />

Arginemia 1<br />

Methylmalonic acidemia<br />

(MMA)<br />

Propionic acidemia (PA) 2<br />

3-methylcrotonyl-CoA<br />

carboxylase deficiency<br />

(3MCC)<br />

Medium chain acyl-CoA<br />

dehydrogenase deficiency<br />

(M<strong>CA</strong>DD)<br />

Short chain acyl-CoA<br />

dehydrogenase deficiency/<br />

Ethyl malonic aciduria<br />

(S<strong>CA</strong>DD/EMA)<br />

Multiple acyl-CoA<br />

dehydrogenase deficiency<br />

(MADD or GA-2)<br />

Total 33<br />

7<br />

1<br />

11<br />

10<br />

1<br />

4 / <strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>

Culturally Appropriate Communication Is<br />

Good Medical Practice<br />

Allan Lieberthal, M.D., F<strong>AAP</strong><br />

California is the most culturally<br />

diverse state in the country. Fortyseven<br />

percent of the population<br />

is white, 32 % Hispanic, 12 % Asian and<br />

Pacific Islander, 7 % African American, and<br />

1% Native-American. As many as 46% of<br />

the population has Limited English Proficiency<br />

(LEP). Over 100 languages are spoken<br />

including, in addition to English and Spanish,<br />

Tagalog, Armenian, Chinese, Thai, Korean,<br />

Arabic, Vietnamese, Hebrew, Russian, Farsi,<br />

and Hindi. We, as pediatricians, face a constant<br />

challenge to communicate with our patients<br />

and parents effectively. Many of us speak<br />

Spanish or another language, in addition to<br />

English. Some of us are fluent in that language<br />

while others try to get by with limited fluency.<br />

We are used to getting by with interpretation<br />

by children, friends, other parents, or a combination<br />

of the parent’s limited English and what<br />

little we may know of their primary language.<br />

The consequence may be that important information<br />

is miscommunicated or omitted during<br />

the medical encounter.<br />

A recent article in Pediatrics 1 points out<br />

the pitfalls of inadequate interpretation. In a<br />

sample of 13 encounters, six with a hospital<br />

interpreter, six with ad-hoc interpreters and one<br />

with an 11-year-old child interpreting, there<br />

were an average of 31 errors per encounter.<br />

Seventy-seven precent of errors made by the<br />

ad hoc interpreters and the child had clinical<br />

significance. This was significantly more than<br />

the 53% of clinically important errors made by<br />

the hospital interpreters. Errors included omission,<br />

false fluency, substitution, and addition.<br />

Recognizing that poor communication<br />

results in inferior medical care, the federal government<br />

has set standards for Culturally and<br />

Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS)<br />

(www.hhs.gov/ocr/lepfinal.htm). Standards<br />

published by the Department of Health and<br />

Human Services (HHS), Office of Civil Rights<br />

(OCR) apply to covered entities that include<br />

“any state or local agency, private institution<br />

or organization, or any public or private individual<br />

that operates, provides or engages in<br />

health, medical or social service programs that<br />

receive or benefit from HHS assistance.” The<br />

federal CLAS standards require covered entities<br />

to identify the language needs of patients<br />

and to provide proficient interpretation in a<br />

timely manner. At the state level, Assembly<br />

Bill 292 (Yee) has been introduced and, if<br />

passed and signed into law, would prohibit the<br />

use of children as interpreters.<br />

There are many approaches to providing<br />

adequate interpreter services. Kaiser-Permanente<br />

in Panorama City has introduced a prototype<br />

program to comply with the standards.<br />

Employees who serve as interpreters must pass<br />

the language proficiency test for interpretation.<br />

These are mostly Spanish speakers. We rarely<br />

have interpreters available for the many other<br />

languages we encounter in our multi-ethnic<br />

practice. In order to meet the needs of all of<br />

our LEP patients, patients are identified as<br />

needing interpretation at the time of making<br />

an appointment and at check-in. A printed<br />

area on the registration papers indicates the<br />

preferred language of the patient and whether<br />

interpretation services are needed. If there is no<br />

interpreter available, we are using Language<br />

Line Services (www.languageline.com), a<br />

telephone-based service that can provide interpretation<br />

in over 140 languages. This can be<br />

done in the exam room using a pair of portable<br />

phone extensions, one for the patient/parent<br />

and one for the physician. The process requires<br />

only a small increase in time as compared to<br />

having an interpreter on site.<br />

Shortly after the Language Line Service<br />

was in place, I was seeing one of my Armenian<br />

patients whose mother speaks very limited<br />

English. It appeared to be a routine sick visit.<br />

Through halting English, I understood the<br />

symptoms of a common cold, but felt a little<br />

uneasy because the mother did not appear to<br />

understand my English instructions. I tried the<br />

Language Line and soon found out that I had<br />

totally misunderstood the illness. In fact the<br />

child had a history consistent with cough variant<br />

asthma. Had I been forced to communicate<br />

in English, I am sure the mother would not<br />

have understood my explanation and instructions.<br />

Using the Language Line it was easy<br />

Over 100 languages are spoken including, in addition to English<br />

and Spanish, Tagalog, Armenian, Chinese, Thai, Korean, Arabic,<br />

Vietnamese, Hebrew, Russian, Farsi, and Hindi.<br />

to get a good history and to explain what her<br />

child had since she was hearing it in her own<br />

language. The mother, who I had seen on several<br />

previous occasions without interpretation<br />

services, was effusive in thanking me and telling<br />

me how happy she was with the visit. From<br />

initial skepticism, I became a convert.<br />

Unlike pediatricians in private practice<br />

or in network managed care practices, I do not<br />

have to deal directly with the cost and reimbursement<br />

for interpretation services. This is<br />

especially important for doctors practicing in<br />

poor communities with a high percentage of<br />

ethnic minorities. Use of the Language Line<br />

may cost as much as $15 for a 10 minute visit.<br />

If a practice has a large number of patients<br />

requiring interpretation by a nurse, workflow<br />

may be impaired or additional personnel may<br />

be needed. This should be recognized as an<br />

additional expense and must be reimbursed<br />

appropriately.<br />

Even consistent professional interpreter<br />

service will not bring us to a single standard<br />

of medical care. The reality is that there is a<br />

severe shortage of qualified health professionals<br />

in all minority groups. Until our patients<br />

can receive competent care from clinicians<br />

who share their culture and language, we must<br />

do our best to be sensitive and responsive to<br />

their needs.<br />

REFERENCE<br />

1. Flores G, Laws B, Mayo SJ, et. al. Errors<br />

in medical interpretation and their potential<br />

clinical consequences in pediatric emergencies<br />

Pediatrics <strong>2003</strong>(1):111:6-14<br />

<strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>/ 5

CMA House of Delegates Report<br />

Paul Y. Qaqundah, M.D.<br />

The 132nd CMA House of Delegates met at the<br />

Hilton Towers in San Francisco on March 22-<br />

25 <strong>2003</strong>. This year, the California <strong>AAP</strong> hosted<br />

its tenth annual breakfast for pediatrician delegates. Your<br />

three specialty representatives, Alan Burkin, Stuart Cohen,<br />

and myself, together with our State Executive Director of<br />

the Academy, Kris Calvin, provided an important opportunity<br />

for county medical society pediatric delegates to dialogue<br />

and coordinate a strategy to influence CMA policy<br />

through the house. Issues discussed included:<br />

1. Extended access to the uninsured, including review of<br />

employer mandate proposals.<br />

2. Medi-Cal physician reimbursement and other state<br />

budget concerns.<br />

3. Options for tapping mental health funds to support<br />

pediatric practice.<br />

4. Coordinated support for resolutions including those<br />

related to reimbursement, obesity, soda sales and junk<br />

foods. Approval of school lunch options, physical<br />

education in schools and Medicaid block grants to<br />

states.<br />

I will highlight the actions of the House on issues that<br />

pertain to pediatrics.<br />

Science and Public Health<br />

The house supported our resolution on childhood obesity<br />

to encourage inclusion of obesity prevention in public<br />

school curricula, support collaborative efforts among<br />

health organizations, promote education, treatment<br />

of obesity, and develop regional centers for comprehensive<br />

treatment of morbid childhood obesity to be<br />

financed through private and public sources.<br />

On our resolution to improve school physical education,<br />

the CMA supported measures that mandate increased<br />

physical activity in schools and explore methods to<br />

protect schools from litigation when school facilities<br />

are made available to communities for after hours<br />

physical activity.<br />

CMA supported <strong>AAP</strong>’s resolution on sale of soda and fast<br />

foods in schools, i.e. to work with health organizations<br />

to strengthen existing standards established by<br />

the “Pupil Nutrition, Health and Achievement Act” of<br />

2001 that all foods provided in public schools (K-12)<br />

meet national government nutritional standards. CMA<br />

urges physicians and local medical societies to work<br />

with local schools to implement these standards.<br />

CMA supported our resolution on Epi-Pen administration<br />

in schools to allow non-CPR certified school personnel<br />

to administer Epi-Pen for anaphylactic reactions<br />

if a CPR certified person is not available. This will<br />

protect schools against litigation.<br />

Emergency contraception. To assist appropriate use of<br />

contraception, CMA supports legislation to prohibit<br />

pharmacists from charging consultation fees when<br />

dispensing emergency contraceptives.<br />

Insurance and physician reimbursement. In 2002 CMA<br />

adopted “Fair Vaccine Payment Resolution” and<br />

requested a report back this year. CMA calls for all<br />

California health plans and Medicare to reimburse<br />

physicians at the average wholesale cost (AWC) of<br />

vaccines plus 10%. CMA also insists on reimbursement<br />

for costs of vaccine administration, at least at the<br />

rate presently paid by Medi-Cal- $9.51.<br />

Child protective services — CMA endorses review of<br />

policies of California Child Protective Services. We<br />

demand that CCPS give substantial weight to recommendations<br />

of treating physicians in the disposition of<br />

any at risk child.<br />

CMA is advocating nationally to fix the absurdities of<br />

HIPAA rules.<br />

The House will work with insurance companies to maintain<br />

a single mailing address for the submission of<br />

claims, the address to be clearly printed on patient<br />

insurance cards. All payers should maintain a single<br />

electronic address and notify physicians of any<br />

changes of addresses.<br />

Newborns who test positive on toxicity screening. CMA<br />

supports immediate entry of the mother into a chemical<br />

dependency treatment program. CMA supports<br />

legislation to increase the number of chemical<br />

dependency treatment and rehabilitation programs<br />

in California.<br />

Jack Levin M.D., CMA’s C.E.O. noted that, “Our<br />

nation remains in a 3 year recession. Our state is broke.<br />

The events of 9/11 made all of that worse. The stress on<br />

health executives from these combined factors have been<br />

horrendous and now we are a nation at war.”<br />

Nevertheless, CMA has fought to protect further<br />

erosion of medical practice by reversing RBRVS cuts<br />

and blocking the impending 4.4% additional cuts in the<br />

<strong>2003</strong> budget. AMA and CMA have saved each physician<br />

involved in Medicare and Medicaid over $15000 in<br />

income. This amounts to the equivalent of CMA dues for<br />

all of a physician’s practice life. When Gov. Davis proposed<br />

$1.6 billion in Medi-Cal cuts the CMA engineered a<br />

complete reversal of those cuts.<br />

CMA has preserved its malpractice rules (MICRA)<br />

despite constant assault by trial lawyers. Thanks to CMA,<br />

California MICRA remains the national gold standard for<br />

malpractice reform. To preserve this, I suggest that you<br />

give generously to <strong>CA</strong>LPAC, the CMA political action<br />

committee.<br />

CMA has additional accomplishments too lengthy<br />

for this report. See www.cmanet.org. President Bush has<br />

stated that it is time to take control of medicine back from<br />

bureaucrats, trial lawyers and HMOs and give it back to<br />

physicians and patients. Don’t believe that anybody will<br />

give you anything. We have to support and join our professional<br />

organizations and take charge of medicine for the<br />

sake of our patients.<br />

6 / <strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>

Weighing the Radiation Risks of CT Scans<br />

Nikta Forghani, M.D., Ronald A. Cohen, M.D., and Myles B. Abbott, M.D.<br />

Computed tomographic (CT) scanning<br />

is a valuable imaging modality<br />

on which pediatricians increasingly<br />

rely. However, pediatricians may not realize<br />

that CT scans expose children to high amounts<br />

of ionizing radiation that may have detrimental<br />

long-term consequences. Recent data from<br />

studies of survivors exposed to low-dose radiation<br />

from the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and<br />

Nagasaki 1 , and the increased risk of leukemia<br />

in children who have two or more radiologic<br />

procedures 2 , suggest that pediatricians should<br />

be more circumspect when ordering CT scans.<br />

More than two million CT scans are done<br />

on children each year in the United States. 3 The<br />

use of CT imaging in both adults and children<br />

has increased by 700% over the past ten years 3 ,<br />

although it has been estimated that 40% of CT<br />

scans performed on children are unnecessary. 4<br />

This increase is in large part due to the fact that<br />

CT imaging has been more widely recognized<br />

as a superior imaging modality for many clinical<br />

problems. While CT imaging has enormous<br />

diagnostic benefit, its widespread use is a<br />

source of potential harm, especially to pediatric<br />

patients. The National Research Council’s<br />

Factors and Procedures<br />

Yearly exposure at sea level 3<br />

Living in Denver (high altitude) 6<br />

Transcontinental flight 0.25<br />

Committee on the Biological Effects of Ionizing<br />

Radiation on Children has determined<br />

that children under 10 years of age are several<br />

times more sensitive to ionizing radiation than<br />

middle-aged adults. 5 In addition, since children<br />

have a longer life span, their potential longterm<br />

risk of radiation damage is increased.<br />

Furthermore, some of the new advances in<br />

CT technology make the scans faster and<br />

more accurate (and therefore more appealing<br />

in the context of pediatric radiology), but may<br />

come with a price of higher ionizing radiation<br />

exposure.<br />

To appreciate the amount of radiation<br />

in a CT scan, it may be helpful to compare<br />

CT radiation with both a standard chest X-<br />

ray and the background radiation to which<br />

we are all exposed in the environment. The<br />

exposure from an abdominal CT scan is 5 to<br />

10 millisieverts (mSv) 1 , which is 250 to 500<br />

times greater radiation than a standard chest<br />

radiograph (which is .02 mSv). The amount of<br />

background radiation varies in different locations,<br />

but the average background radiation in<br />

the United States (excluding medical sources)<br />

is about 3 mSv per year. The table shows the<br />

Table: Representative Values of Effective Radiation Doses Associated with<br />

Various Environmental Factors and Medical Procedures 7, 8<br />

Chest X-ray 0.02 – 0.05<br />

Skull X-ray<br />

Abdominal X-ray<br />

Intravenous pyelogram<br />

Upper gastrointestinal series<br />

Barium Enema<br />

Head CT<br />

Chest CT<br />

Abdominal CT<br />

Ultrasonography 0<br />

Magnetic Resonance Imaging 0<br />

Effective dose in mSv<br />

0.1– 0.2<br />

0.5 – 1.5<br />

2.5 – 5.0<br />

3.0<br />

3.0 – 7.0<br />

2.0 – 4.0<br />

5.0 – 15.0<br />

5.0 – 15.0<br />

approximate amount of radiation associated<br />

with various environmental factors, medical<br />

procedures involving ionizing radiation, and<br />

medical procedures that do not expose patients<br />

to radiation.<br />

Much of the current concern about the<br />

effects of ionizing radiation on children stems<br />

from recently published research about cancer<br />

risk in atomic bomb survivors. Today, more<br />

than 50 years after their initial exposure,<br />

individuals have been identified who received<br />

radiation doses that are similar to doses<br />

achieved with modern CT scans (8-30 mSv).<br />

The research shows that these individuals have<br />

a small but statistically significant increased<br />

mortality risk from cancer.<br />

Pediatricians and pediatric radiologists<br />

ought to work collaboratively to determine the<br />

best imaging technique for each patient. When<br />

non-radiation modalities (ultrasonography or<br />

MRI) are as diagnostic as CT for the child’s<br />

condition, they should be preferred. However,<br />

CT scans are often the most appropriate imaging<br />

modality. When CT is used, there are ways<br />

to reduce the exposure to radiation:<br />

• Reduce CT settings, which can be<br />

done without significantly compromising<br />

image quality. In one recent trial, ionizing<br />

radiation exposure in children was reduced by<br />

75% while quality was maintained. 6<br />

• Utilize more focused or limited CT<br />

scans to minimize the extent of radiation exposure.<br />

For example, when trying to identify a<br />

hepatic abnormality, CT can focus on the liver<br />

rather than the entire abdomen and pelvis.<br />

• Perform only the minimum number<br />

of CT scans necessary for the diagnosis. There<br />

are very few circumstances when multiple CT<br />

scans are necessary.<br />

• Be judicious in repeating CT scans<br />

to follow a pathologic process. Consider other<br />

imaging modalities to follow the process.<br />

REFERENCES:<br />

1. Pierce DA, Preston DL. Radiation-related<br />

cancer risks at low doses among atomic<br />

bomb survivors. Radiation Research. 2000;<br />

154:178-186.<br />

2. Infante-Rivard C, Mathonnet G, Sinnett D.<br />

Risk of childhood leukemia associated with<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 28<br />

<strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>/ 7

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis<br />

While it is normal for the spine<br />

to have curvatures in the lateral<br />

plane (lordosis in the lumbar and<br />

cervical regions and kyphosis in the thoracic<br />

region), the spine is normally straight when<br />

viewed from the frontal plane. Scoliosis is a lateral<br />

curvature of the spine, and is always abnormal.<br />

The term scoliosis is derived from the<br />

Greek term ‘scolio’ (curved or bent). There are<br />

many causes of scoliosis but the most common<br />

is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), which<br />

accounts for a great majority of cases. This is<br />

a structural (stiff) curve with rotation of the<br />

spine that occurs at or near the onset of puberty<br />

without an established cause. A variety of possible<br />

etiological factors have been implicated,<br />

including hormones, genetic predisposition,<br />

muscular imbalance and neurologic abnormalities.<br />

However, no direct link between these factors<br />

and the development of scoliosis have been<br />

established in this population.<br />

The diagnosis of AIS is suspected by the<br />

presence of asymmetry on the Adams forward<br />

bend test. However, some children may have<br />

muscular asymmetry without a true scoliosis.<br />

In addition, care should be taken to account<br />

for any leg-length discrepancy (LLD) as this<br />

can also produce asymmetry of the spine and<br />

a lateral curvature. If scoliosis is suspected,<br />

a standing postero-anterior (PA) radiograph<br />

should be obtained. A curve of 10 degrees or<br />

greater confirms the diagnosis of scoliosis. The<br />

prevalence in the adolescent population (10 to<br />

16 yrs) is approximately 2 to 3%. The female:<br />

male ratio for smaller curves is almost equal,<br />

whereas the female:male ratio for larger curves<br />

is 3.6:1.<br />

The history should include any family<br />

history of scoliosis or other back problems,<br />

prior lower extremity fracture, any neurologic<br />

complaints (including bowel and bladder<br />

function) as well as any history of back pain.<br />

Pain is not normally associated with AIS,<br />

whereas painful scoliosis may be the result of<br />

a herniated disk or tumor. A careful physical<br />

examination should include an evaluation for<br />

LLD and inspection of the back and skin for<br />

any abnormal skin markings, dimples or hairy<br />

patches that may indicate an underlying spinal<br />

cord abnormality. The entire body should be<br />

inspected for the presence of cafe au lait spots<br />

or other manifestations of neurofibromatosis.<br />

Finally, a detailed neurologic examination<br />

including upper and lower extremity motor<br />

Robert M. Bernstein, M.D.<br />

strength, sensation, and reflexes should be<br />

undertaken. Abdominal reflexes (stroking each<br />

side of the umbilicus gently with a blunt object<br />

should result in equal movement of the umbilicus<br />

toward the stimulated side) should also<br />

be checked as asymmetry of this reflex may<br />

indicate intra-spinal pathology.<br />

Pain, asymmetry of abdominal reflexes,<br />

or any abnormal neurologic finding may indicate<br />

an underlying spinal cord abnormality and<br />

should be investigated. The incidence of spinal<br />

cord abnormality (syrinx or chiari malformation)<br />

is extremely low in AIS, and in general,<br />

only a plain radiograph (PA) need be obtained.<br />

PA radiographs are preferred over anteroposterior<br />

radiographs because the radiation<br />

exposure of the breast is minimized. Curves<br />

measuring less than 10 0 should be considered<br />

a normal variant and do not require further<br />

evaluation. In addition, it should be kept in<br />

mind that labeling the child with a diagnosis of<br />

scoliosis may have implications with respect to<br />

future insurability.<br />

The majority of children with AIS will<br />

never require active treatment (less than 10%).<br />

The natural history is related to a number of<br />

factors: the age (maturity) of the patient, the<br />

location of the curve, the curve pattern, and the<br />

size of the curve. Younger patients have more<br />

potential growth and thus have a greater risk<br />

of curve progression. Curves in the thoracic<br />

region are stabilized by the ribs and thus are<br />

less likely to progress than lumbar and thoraco-lumbar<br />

curves. Double curves are more<br />

likely to progress than single curves, and larger<br />

curves are more likely to progress than smaller<br />

ones.<br />

Once the patient reaches skeletal maturity,<br />

curve progression slows dramatically or stops.<br />

Thoracic curves under 30 0 don’t progress after<br />

skeletal maturity. Those curves between 30 0<br />

and 50 0 may progress but do so very slowly.<br />

However, thoracic curves between 50 0 and 75 0<br />

have the greatest risk of progression and may<br />

do so at up to 1 0 per year. The biggest concern<br />

with thoracic curves is the loss of normal<br />

thoracic kyphosis. Loss of kyphosis with progression<br />

of the curve can result in a decrease<br />

in pulmonary function. This loss of function<br />

is measurable when the curve reaches 60 0 to<br />

70 0 , but will not be noticeable to the patient<br />

until the curve reaches over 100 0 . Lumbar<br />

and thoraco-lumbar curves under 30 0 tend not<br />

to progress after maturity. Those greater than<br />

30 0 will progress but the extent of progression<br />

is difficult to predict. They may result in a<br />

significant trunk asymmetry that is cosmetically<br />

displeasing to the patient and family. The<br />

association between curve magnitude and a<br />

decrease in pulmonary function only occurs<br />

with thoracic curves and does not apply to<br />

lumbar and thoraco-lumbar curves.<br />

Treatment may involve simple observation,<br />

bracing, or surgery. While exercises and<br />

electrical stimulation have been utilized in the<br />

past, there is no evidence that these modalities<br />

affect curve progression. In addition, recent<br />

literature has not shown any benefit from<br />

chiropractic manipulation. As the majority<br />

of AIS curves are small and thus have a low<br />

likelihood of progression, most patients will<br />

simply require regular follow-up visits with<br />

radiographs to look for curve progression.<br />

Bracing is instituted in skeletally immature<br />

patients in order to prevent the curve<br />

from achieving a magnitude that will continue<br />

to progress after maturity. Once the brace is<br />

removed, the curve usually returns to its prebrace<br />

magnitude. A brace is recommended<br />

when progression has been documented in<br />

curves under 30 0 , for those curves measuring<br />

30 0 -40 0 on initial presentation, and occasionally<br />

for somewhat larger curves. Curves over<br />

50 0 are likely to progress even after maturity<br />

and thus are generally not brace candidates.<br />

The current surgical treatment for scoliosis<br />

is spinal fusion, usually with instrumentation.<br />

The primary goal of fusion is to<br />

prevent further progression of the curve, and a<br />

secondary goal is to improve cosmetic appearance,<br />

usually by decreasing the size of the<br />

curve using rods, hooks, wires, and/or screws.<br />

Reducing the curve size is only important to<br />

the patient in how it affects their appearance,<br />

and this must be balanced with the risk of<br />

neurologic injury. As a general rule, the curve<br />

can safely be reduced by about 50% its original<br />

size. The indications for surgery vary and are<br />

related to curve magnitude, progression, curve<br />

pattern, and cosmetic appearance. Once a thoracic<br />

curve has reached 50 0 , the risk of progression<br />

after skeletal maturity is high and most of<br />

these patients should undergo fusion. Curves<br />

over 40 0 that progress in spite of bracing are<br />

also fusion candidates. The indications for surgery<br />

in the lumbar and thoraco-lumbar spine<br />

is more controversial. If little trunk imbalance<br />

is present, no intervention may be the best<br />

approach, as fusing into the lumbar spine significantly<br />

affects mobility and may increase the<br />

risk of back pain. However, curves that create<br />

significant trunk imbalance may be candidates<br />

for surgery from a cosmetic standpoint.<br />

The choice between posterior spinal<br />

fusion, anterior spinal fusion, or both is somewhat<br />

surgeon dependant and is also related to<br />

the location of the curve, risk factors for non-<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 26<br />

8 / <strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>

Preventing Ear Infections in Children<br />

Harry Pellman, M.D.<br />

Acute Otitis Media (AOM) is the<br />

most common bacterial infection<br />

diagnosed in children and the most<br />

common reason antibiotics are prescribed in<br />

this age group. Despite these facts, there is still<br />

quite a bit of controversy on how to best make<br />

the diagnosis of AOM and a good strategy for<br />

treating these infections. The American Academy<br />

of Pediatrics is intently working on new<br />

guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of<br />

acute otitis media (AOM) in children.<br />

There are a variety of strategies known to<br />

reduce the frequency of middle ear problems.<br />

Implementing as many of these strategies as<br />

possible may be like closing the barn door<br />

before the cows get out.<br />

Breast feeding has been clearly shown to<br />

reduce both the incidence of AOM and<br />

otitis media with effusion (OME) in<br />

multiple studies. The protective effect is<br />

related to the duration and exclusivity of<br />

breast feeding and is most prevalent in<br />

infancy.<br />

Avoid environmental tobacco poisoning<br />

(aka cigarette smoking). This type of air<br />

pollution is clearly related to more AOM<br />

and OME.<br />

When bottle feeding, use fully vented bottles.<br />

Fully vented bottles allow air inflow<br />

as the milk exits the bottle and prevents<br />

negative middle ear pressure. Negative<br />

pressure in the middle ear promotes the<br />

entrance of nasopharyngeal contents into<br />

the middle ear chamber. Children using<br />

fully vented bottles have middle ear pressures<br />

that appear to be similar to infants<br />

breast feeding.<br />

Use of pacifiers beyond 18-24 months of age<br />

has been associated with more middle ear<br />

disease. The reason for this association is<br />

not clear. Whether this occurs because<br />

of abnormal pressures generated in the<br />

middle ear, more viral infections associated<br />

with pacifier use, or another mechanism<br />

is unknown.<br />

There are a variety of strategies known to reduce the frequency<br />

of middle ear problems. Implementing as many of these<br />

strategies as possible may be like closing the barn door before<br />

the cows get out.<br />

There is a suggestion that babies that have gastroesophageal<br />

reflux disease (GERD)<br />

have a higher incidence of middle ear<br />

disease. In one study, middle ear fluid<br />

obtained from children having myringotomy<br />

and tube insertion revealed pepsin<br />

and pepsinogen levels 1000 times higher<br />

than serum levels in more than 80% of<br />

children. Ongoing investigations will help<br />

clarify this issue.<br />

Daycare is associated with both an increased<br />

incidence of middle ear disease and the<br />

presence of more resistant bacteria when<br />

infections occur. Of course, daycare<br />

is essential for many working parents.<br />

Training daycare workers to wash hands<br />

frequently and employ hygienic measures<br />

is a Herculean task.<br />

Vaccines will have a dramatic impact on<br />

AOM. Prevnar vaccine provides significant<br />

protection against the seven strains of<br />

streptococcus pneumonia (in the past, the<br />

most common bacteria isolated in AOM)<br />

in the vaccine plus five cross-reacting<br />

strains. The vaccine has only reduced the<br />

overall incidence of AOM about 5-10%.<br />

However, the serotypes of streptococcus<br />

pneumonia present in the vaccine are both<br />

some of the most common bacteria present<br />

in AOM and the most resistant and<br />

difficult to treat bacteria we encounter.<br />

This vaccine has reduced the necessity<br />

for ear tubes about 20%, the frequency<br />

of having multiple episodes of AOM in<br />

an infection-prone child up to 20%, and<br />

changed the bacteriology of AOM so that<br />

non-typable hemophilus influenza bacteria<br />

is now the most common bacteria isolated<br />

in AOM in children vaccinated with<br />

prevnar. Work is presently being done<br />

on a nine-valent pneumococcal vaccine<br />

and a non-typable hemophilus influenza<br />

vaccine. Their impact on reducing AOM<br />

remains to be seen.<br />

Since most episodes of AOM follow viral<br />

respiratory illnesses, it appears that<br />

reducing these illnesses will lessen the<br />

frequency of AOM. Influenza vaccine,<br />

especially the newly released coldadapted<br />

live influenza vaccine, has been<br />

shown to effectively lessen the incidence<br />

of AOM. If a safe, effective RSV vaccine<br />

is ever approved by the FDA, we should<br />

expect a further reduction in AOM episodes.<br />

Xylitol is a natural, non-absorbable sugar most<br />

commonly harvested from birch trees.<br />

Xylitol chewing gum has been used in<br />

Finland for many years to reduce the<br />

incidence of dental caries, an infectious<br />

disease caused by strep mutans. Children<br />

on long term xylitol chewing gum were<br />

found to have as much as 40% fewer<br />

episodes of AOM. However, if used only<br />

during a high risk period, such as a viral<br />

respiratory infection, xylitol may not be<br />

protective. The usefulness of xylitol in<br />

other forms (syrup, lozenges, etc.) is still<br />

being investigated.<br />

There is a suggestion that iron deficiency<br />

anemia may be associated with an<br />

increased risk of AOM.<br />

It sounds like the ideal situation for maximum<br />

middle ear health is an infant exclusively<br />

breast fed for at least six months, living in a<br />

healthful environment without daycare, no<br />

pacifiers, bottles (if used) should be fully<br />

vented, kept on an iron rich diet, fully vaccinated,<br />

properly positioned to lessen GERD,<br />

and chewing xylitol chewing gum when old<br />

enough to do so.<br />

If employing the above strategies fails to<br />

reduce the incidence of ear infections, since<br />

frequent AOM seems to have some kind of<br />

genetic link, the child should consider choosing<br />

different parents!<br />

<strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>/ 9

A Low-Glycemic Index Diet in the<br />

Treatment of Pediatric Obesity<br />

Leshe E. Spieth, PhD; Jennifer D. Harnish, PhD; Carine M. Lenders, MD, MS; Lauren B. Raezer, PhD;<br />

Mark A. Pereira, PhD; S. Jan Hangen, MS, RD; David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD<br />

This article has been excerpted from one<br />

printed in Archives of Pediatric Adolescent<br />

Medicine, September 2000, pages 47-51.<br />

Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2000,<br />

American Medical Association.<br />

EXCESSIVE BODY weight is arguably<br />

the most prevalent medical problem<br />

in the United States today. Approximately<br />

25% of children and more than 50% of<br />

adults are considered overweight according to<br />

data from the most recent National Health and<br />

Nutrition Examination Survey. 1,2 Overweight<br />

and obesity in childhood contribute to a range<br />

of immediate and long-term problems, including<br />

diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension,<br />

sleep apnea, musculoskeletal problems,<br />

gastrointestinal disease, and psychosocial<br />

difficulties. Overweight children, especially<br />

those older than seven years, are at increased<br />

risk for obesity and cardiovascular disease in<br />

adulthood.<br />

The standard approach to the treatment<br />

of obesity involves the reduction of dietary<br />

fat, the most energy-dense nutrient. The US<br />

Department of Agriculture, the American<br />

Heart Association (Dallas, Tex), and the<br />

American Diabetes Association (Alexandria,<br />

VA) currently recommend reduced-fat diets in<br />

the prevention and treatment of obesity. However,<br />

weight loss on reduced-fat diets is characteristically<br />

modest and transient. Moreover,<br />

prevalence rates of overweight and obesity<br />

have risen dramatically in recent years, despite<br />

decreases in dietary fat as a percentage of total<br />

energy to near recommended levels.<br />

Recently, a low-glycemic index (GI) diet<br />

has been proposed as a novel treatment for<br />

obesity. Glycemic index refers to the relative<br />

rise in blood glucose occurring after consumption<br />

of a food containing a standard amount of<br />

carbohydrate. Most refined grain products and<br />

potatoes have a high GI, whereas nonstarchy<br />

vegetables, legumes, and fruits generally have<br />

a low GI. The glycemic response to a meal<br />

increases with the carbohydrate content and<br />

GI of the component foods, but decreases with<br />

fiber, protein, and fat content. 19-22 Glycemic<br />

index may affect hunger through effects on<br />

pancreatic hormone secretion that, in turn,<br />

alter availability of metabolic fuels after a<br />

meal. Of 16 studies published to date relating<br />

GI to hunger, satiety, or voluntary food<br />

intake, 15 demonstrated beneficial effects of<br />

low-compared with high-GI meals. However,<br />

the effects of GI on body weight have not been<br />

examined.<br />

The purpose of this study was to evaluate<br />

the effects of a low-GI diet in a pediatric outpatient<br />

setting. Specifically, we sought to test the<br />

hypothesis that a low-GI diet would result in<br />

greater weight loss compared with a reducedfat<br />

diet among obese children remaining in<br />

outpatient treatment for at least one month.<br />

Participants and Methods<br />

STUDY DESIGN<br />

During the period between September 1, 1997<br />

and August 31, 1998, children attending the<br />

Optimal Weight for Life Program at Children’s<br />

Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, for treatment<br />

of obesity were assigned by the program<br />

administrator, based on schedule availability,<br />

to one of two teams, each composed of a subspecialty-trained<br />

pediatrician, a dietitian, and<br />

at times a pediatric nurse<br />

practitioner. One team<br />

prescribed a low-GI diet,<br />

the other a reduced-fat<br />

diet. Except for specific<br />

dietary recommendations,<br />

each team provided similar<br />

diagnostic evaluation and<br />

treatment. To estimate the<br />

effects of dietary treatment<br />

on body fatness, we<br />

retrospectively examined<br />

the changes in body mass<br />

index (BMI [calculated<br />

as weight in kilograms<br />

divided by the square of<br />

height in meters]) and<br />

body weight from the participant’s<br />

initial visit to last<br />

visit before December 31,<br />

1998, according to dietary<br />

treatment assignment.<br />

PARTICIPANTS<br />

A total of 190 patients<br />

(excluding those with<br />

Cushing syndrome, hypothyroidism,<br />

hypothalamic<br />

disease, diabetes mellitus or an obesity-associated<br />

genetic syndrome, or those currently<br />

following a very low-energy diet) were<br />

evaluated during the study period. We further<br />

excluded 83 individuals for lack of follow-up<br />

(< 1 month) and/or incomplete data, leaving a<br />

cohort of 107. Descriptive characteristics of<br />

this cohort are presented in Table 1.<br />

STANDARD TREATMENT COMPONENTS<br />

All patients received a comprehensive medical<br />

evaluation (medical history, physical examination,<br />

and laboratory investigation), dietary<br />

counseling, and lifestyle counseling (recommendations<br />

were based on decreasing physical<br />

inactivity and increasing physical activity).<br />

Counseling sessions included the child and<br />

at least one parent, when possible, according<br />

to established practice. Specific goals were<br />

individualized, with consideration given to the<br />

patient’s developmental level and readiness to<br />

change. Follow-up appointments were generally<br />

recommended to occur on a monthly basis for<br />

the first four months, and then as needed.<br />

10 / <strong>CA</strong>LIFORNIA <strong>PEDIATRICIAN</strong> — SPRING <strong>2003</strong>

In addition, problem-focused behavior<br />

therapy was provided by the program psychologist<br />

on an individual basis when referred<br />

by a team member. Within these sessions, a<br />

particular nutritional or physical activity goal<br />

was identified as a primary treatment target. A<br />

behavioral program was then developed, using<br />

positive reinforcement for meeting the specified<br />

goal. Specifics of treatment were adapted<br />

according to the patient’s age and developmental<br />

stage.<br />

DIETARY TREATMENTS<br />

One team prescribed a standard balanced,<br />

hypoenergetic reduced-fat diet because of<br />

research demonstrating improvements in<br />

adiposity on this diet when combined with<br />

behavioral modification and exercise. 26, 27 The<br />

diet followed US Department of Agriculture<br />

recommendations for intake of specific food<br />

types, as depicted by the Food Guide Pyramid.<br />

Particular emphasis was placed on limiting<br />

intake of high-fat, high-sugar, and energydense<br />

foods, and increasing intake of grain<br />

products, vegetables, and fruit.<br />

Recommendations were tailored on an<br />

individual basis to incorporate an energy<br />

restriction of approximately 1042 kJ (250<br />

kcal) to 2084 kj (500 kcal) per day compared<br />

with usual energy intake. Specific macronutrient<br />

goals were 55% to 60% carbohydrate, 15%<br />

to 20% protein, and 25% to 30% fat.<br />

The other team prescribed a low-GI diet<br />

because of preliminary research suggesting<br />

a physiologic mechanism relating GI to<br />

body weight regulation. 16,17 The low-GI diet<br />

was designed to obtain the lowest glycemic<br />

response possible while providing adequate<br />

dietary carbohydrates, satisfying all nutritional<br />

recommendations for children, and maintaining<br />

palatability. This diet differed from the<br />

standard diet not just in the GI of the component<br />

carbohydrates foods, but also in the macronutrient<br />

ratio. Emphasis was placed on food<br />

selection, not energy restriction: patients were<br />

instructed to eat to satiety and snack when<br />

hungry. Specifically, patients were told to<br />

combine low-GI carbohydrate, protein, and fat<br />

at every meal and snack. A “Low-GI Pyramid,”<br />

modeled after the Food Guide Pyramid, was<br />

used as a teaching tool. This modified pyramid<br />

placed vegetables, legumes, and fruits at the<br />

base, lean proteins and dairy products on the<br />

second level, whole-grain products on the third<br />

level, and refined grain products, potatoes, and<br />

concentrated sugars at the top. Specific macronutrient<br />

goals were 45% to 50% carbohydrate,<br />

20% to 25% protein, and 30% to 35% fat.<br />

Results<br />

Characteristics of the cohort are described in<br />

Table 1 according to dietary treatment group.<br />

Mean age, length of follow-up, number of<br />

visits, and sex were similar between the two<br />

treatment groups. Baseline BMI and body<br />

weight were slightly greater in the reduced-fat<br />

group compared with the low-GI group, but<br />

the difference was not statistically significant.<br />

Ethnicity differed in the study cohort primarily<br />

owing to different follow-up rates (of the 190<br />

patients before exclusion for lack of follow-up,<br />

white subjects comprised 71% of 118 individuals<br />

assigned to the low-GI group vs. 67% of 72<br />

individuals assigned to the reduced fat group).<br />

The figure depicts the mean change in<br />

BMI from the participant’s first to last clinic<br />

visit according to dietary treatment and baseline<br />

BMI tertile. For each BMI tertile, the low-<br />

GI group had a significantly larger decrease in<br />

BMI than the reduced-fat group. Compared<br />

with the reduced-fat group, a larger percentage<br />

of patients in the low-GI group experienced a<br />

decrease in BMI of at least -3 kg/m2 (11 participants<br />

[17.2%] vs. one participant [2.3%]. As<br />

presented in Table 2, the overall mean change<br />

in BMI for the low-GI group was -1.53 kg/m2,<br />

compared with -0.06 kg/m2 for the reducedfat<br />

group (P

Why California’s MICRA Is Good for the Nation<br />

Ron Bangasser, M.D.<br />

The National Medical<br />

Liability Crisis<br />

It is upsetting to watch physicians walk<br />

off their jobs to protest the cost of medical<br />

liability insurance in New Jersey, Nevada,<br />

Mississippi, West Virginia and Florida. But it<br />

would be far more upsetting if there were no<br />

doctors at all to provide surgery, trauma care,<br />

diagnose illnesses and deliver babies. Some<br />

of these physicians are being charged up to<br />

$200,000 annually for their liability coverage,<br />

and like the proverbial canary in the coalmine,<br />

these physicians are trying to warn us about a<br />

coming national health care crisis.<br />

California faced a similar calamity in the<br />

1970s. Malpractice insurance was soaring with<br />

some physicians expecting 400% premium<br />