by Catherine Madsen - Yiddish Book Center

by Catherine Madsen - Yiddish Book Center

by Catherine Madsen - Yiddish Book Center

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

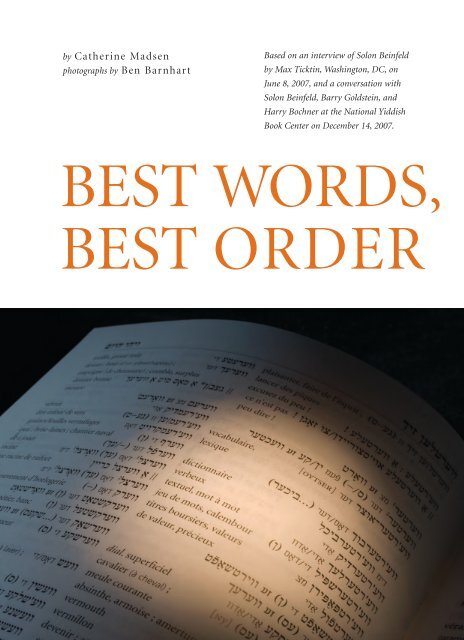

y <strong>Catherine</strong> <strong>Madsen</strong><br />

photographs <strong>by</strong> Ben Barnhart<br />

Based on an interview of Solon Beinfeld<br />

<strong>by</strong> Max Ticktin, Washington, DC, on<br />

June 8, 2007, and a conversation with<br />

Solon Beinfeld, Barry Goldstein, and<br />

Harry Bochner at the National <strong>Yiddish</strong><br />

<strong>Book</strong> <strong>Center</strong> on December 14, 2007.<br />

BEST WORDS,<br />

BEST ORDER

In 1908, a group of eminent <strong>Yiddish</strong>ists assembled in Czernowitz, Bukovina (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now in<br />

Ukraine) to argue about the spelling, grammar, vocabulary, status, and future of the <strong>Yiddish</strong> language. Among the items on their<br />

agenda was the production of a dictionary.<br />

A hundred years later, we are about to have the first comprehensive dictionary of modern <strong>Yiddish</strong>. Thanks to a handful of intrepid<br />

scholars and programmers, the Yidish-English verterbukh/<strong>Yiddish</strong>-English Dictionary is taking shape.<br />

Actually, the book will be a reworking of a <strong>Yiddish</strong>-French dictionary. In 2002, the Bibliothèque Medem in Paris published Yitskhok<br />

Niborski and Bernard Vaisbrot’s Yidish-Frantseyzish verterbukh/Dictionnaire <strong>Yiddish</strong>-Français, an exemplary work that was immediately<br />

adopted <strong>by</strong> English-speaking <strong>Yiddish</strong>ists as well. It listed so many words not represented in previous dictionaries that the extra step of<br />

translating from French to English was worth the trouble. Solon Beinfeld, director of the new dictionary project, aims to make that extra<br />

step unnecessary. The process of compiling the dictionary will be relatively quick: starting from Niborski’s abundant (and electronically<br />

stored!) lexical base, the time involved in producing an English version will be substantially less than starting from scratch.<br />

The story of <strong>Yiddish</strong> lexicography is complex, contentious, occasionally comic, and sometimes tragic. The first glossaries of<br />

<strong>Yiddish</strong> appeared in the 17th century, for the use of German merchants – and policemen: <strong>Yiddish</strong> words had entered the argot of the<br />

criminal underworld. Lexicography was just beginning to evolve in those days (Samuel Johnson’s English dictionary was not published<br />

till 1755), and there were wide variations among dictionaries in length, format, and purpose. Not until the end of the 19th<br />

century – <strong>by</strong> which time the first fascicles of the Oxford English Dictionary were being published – did the first major <strong>Yiddish</strong>-English<br />

dictionaries appear. They were written in New York <strong>by</strong> the great Alexander Harkavy, an immigrant from a learned Lithuanian family<br />

who also wrote a number of home-study manuals for <strong>Yiddish</strong> speakers learning English.<br />

Harkavy not only documented but championed the <strong>Yiddish</strong> language, at a time when most educated Jews were focused on the<br />

revival of Hebrew. His dictionaries were invaluable to their intended audience of immigrants and remain so for contemporary students<br />

in search of a broader <strong>Yiddish</strong> vocabulary. His entries are very brief, providing simply the <strong>Yiddish</strong>, the English, the part of speech, and<br />

sometimes an idiomatic usage. (Hakn, for example, is defined as “to cut, chop; to knock; to talk (fig.),” and hakn a morde is “to knock<br />

a person on the jaw.”) Harkavy did not supply grammatical particulars like the genders of nouns, nor the pronunciations<br />

of Hebrew and Aramaic imports, features that would be useful nowadays. But he had an eclectic sense of the<br />

Yitskhok Niborski <strong>Yiddish</strong> vocabulary, and his dictionaries are the best existing guide to actual usage in prewar <strong>Yiddish</strong> literature and<br />

and Bernard<br />

culture. His last dictionary, the trilingual 1928 <strong>Yiddish</strong>-English-Hebrew, has been reprinted twice <strong>by</strong> the YIVO Institute<br />

Vaisbrot’s 2002 and is still one of the primary <strong>Yiddish</strong> reference works.<br />

<strong>Yiddish</strong>-French<br />

But the rapid evolution of <strong>Yiddish</strong> did not stop in1928. Poets, writers, and ordinary speakers continued to push the<br />

dictionary. Right, boundaries of the language: adopting words from other languages, bending the meanings of existing words for new purposes,<br />

inventing new slang and bilingual puns. Snippets of non-Jewish dialect continued to attach themselves to adjacent<br />

Uriel Weinreich’s<br />

1968 <strong>Yiddish</strong>- <strong>Yiddish</strong> dialects; modern translators regularly consult Polish, Ukrainian or Russian dictionaries when translating as<br />

English dictionary. simple a thing as a letter. Decades of intense social and literary activity – to say nothing of the upheavals and terrible<br />

losses of a world war – worked major changes in <strong>Yiddish</strong> vocabulary and usage.<br />

Uriel Weinreich, who next took up the challenge, was more concerned to limit than to expand lexical <strong>Yiddish</strong>.<br />

His father, the linguist Max Weinreich, had founded the YIVO Institute in Vilna (now in New York) for the study and<br />

preservation of <strong>Yiddish</strong> cultural materials. Uriel Weinreich worked at Columbia University just as the field of <strong>Yiddish</strong><br />

studies was taking shape, and aimed to define the boundaries of the language. His 1968 Modern English-<strong>Yiddish</strong>,<br />

<strong>Yiddish</strong>-English Dictionary was a milestone in the establishment of correct usage. Whereas Harkavy was inclusive<br />

to the point of whimsy (among many other anglicisms, his 1928 dictionary includes sanovegon, “son of a gun”),<br />

Weinreich was austerely prescriptive, excising common German, Slavic and English imports as insufficiently authentic.<br />

He did coin words, notably for technological innovations, though not all of these have taken root in the language.<br />

His impeccable scholarship nevertheless produced a masterful dictionary, thorough<br />

and helpful in including many idioms that would otherwise confound the beginner.<br />

Tragically, Weinreich died at the age of 40, while his dictionary was still in proof.<br />

His family and friends saw it through publication under YIVO’s auspices. The book<br />

remains in print and is still indispensable for <strong>Yiddish</strong> readers at all levels, but it has<br />

never been revised. One can only wonder how Weinreich’s thinking and methods might<br />

have changed over the course of 30 or 40 more years.

Nahum Stutchkoff’s 900-page thesaurus,<br />

Der oytser fun der Yidisher<br />

shprakh (The Treasury of the <strong>Yiddish</strong><br />

Language, 1950), provides a rich supplement<br />

to the standard dictionaries.<br />

Stutchkoff was a <strong>Yiddish</strong> actor, playwright,<br />

and radio announcer noted<br />

for his eloquence who also compiled<br />

the only <strong>Yiddish</strong> rhyming dictionary.<br />

However, as generations of Englishspeaking<br />

students have found with<br />

Roget ’s, it is dangerous to try and<br />

extrapolate definition and usage from<br />

a thesaurus; the unwary writer can<br />

make really embarrassing mistakes. As<br />

Nokhem Stutchkoff’s a source of vocabulary the Oytser is<br />

Der oytser fun der splendid, but the nuances of meaning<br />

Yidisher shprakh. must be filled in from other sources.<br />

Yudl Mark, a major figure in <strong>Yiddish</strong> linguistics and education<br />

and author of the invaluable 1978 textbook Gramatik fun<br />

der Yidisher klal-shprakh (Grammar of Standard <strong>Yiddish</strong>),<br />

worked for many years on the <strong>Yiddish</strong>-<strong>Yiddish</strong> Groyser verterbukh<br />

fun der Yidisher shprakh (Great Dictionary of the <strong>Yiddish</strong><br />

Language). Four volumes, covering only the letter alef, were<br />

published between 1961 and 1980. This is a much larger<br />

achievement than English speakers might guess, since a<br />

number of common <strong>Yiddish</strong> prefixes (and the vast majority of<br />

words beginning with vowel sounds) have an initial alef :<strong>by</strong><br />

stripping away the prefixes one can identify verb roots for the<br />

whole alphabet. Fifteen or so prefixes – among them oys, oyf,<br />

on, op, arum, avek, aroyf, aroys, arayn, arop, ariber – can attach<br />

themselves to the verb geyn,“to go”; the prefixes yield various<br />

subtleties of expression, but the underlying root geyn is easy to<br />

spot. When this factor is taken into account, the four alef volumes<br />

cover about one-third of the <strong>Yiddish</strong> lexicon.<br />

Yudl Mark died in 1975. A group of his colleagues<br />

attempted to continue his work, with ambitious plans –<br />

beyond the capacity of the software then available – but did<br />

not manage to complete any subsequent volumes. The project<br />

eventually lost its funding and was never revived, again<br />

an immense loss to the <strong>Yiddish</strong> world. Rumors (and recriminations)<br />

still circulate about the failure of the project and the<br />

location and extent of the remaining materials.<br />

For many years, Mordkhe Schaechter was the man to contact<br />

for the meanings of obscure <strong>Yiddish</strong> words and for new<br />

coinages. Born in Czernowitz in 1927, he came to New York<br />

in 1951, had a long association with YIVO, and taught in the<br />

YIVO/Columbia Weinreich summer program in <strong>Yiddish</strong><br />

from its inception in 1968 until 2004. After Schaechter’s<br />

death in 2007, an obituary in the Forward described him as a<br />

“one-man Academy of the <strong>Yiddish</strong> Language.”<br />

Schaechter was fascinated <strong>by</strong> minutiae, and published a<br />

substantial list of <strong>Yiddish</strong> botanical terminology as well as a<br />

book of terms relating to pregnancy, birth, and early childhood.<br />

Among the work he left behind is an enormous card<br />

file of the sexual terminology in use among yeshiva students<br />

(needed for – among other purposes, one supposes –<br />

Talmudic debate). Schaechter was associate editor of the<br />

Groyser verterbukh in the 1980s, and not surprisingly was at<br />

work on his own dictionary. His descendants are organizing<br />

his materials into an English-<strong>Yiddish</strong> dictionary that will<br />

undoubtedly be a magnificent counterpart to Beinfeld’s<br />

<strong>Yiddish</strong>-English.<br />

Yitskhok Niborski, compiler of the <strong>Yiddish</strong>-French dictionary<br />

from which Beinfeld’s group is working, was born in<br />

1947 in Argentina – the Library of Congress lists him as<br />

Isidoro – and attended the excellent <strong>Yiddish</strong> day schools of<br />

Buenos Aires, whose students spoke <strong>Yiddish</strong> even on the<br />

playground. As an adult he taught in those same schools, and<br />

co-authored a <strong>Yiddish</strong>-Spanish, Spanish-<strong>Yiddish</strong> dictionary.<br />

Gradually it became clear that the schools were being compelled<br />

to shift from <strong>Yiddish</strong> to Hebrew education. Niborski<br />

moved to Paris to work at the Bibliothèque Medem, a vibrant<br />

center of <strong>Yiddish</strong> activity and the largest <strong>Yiddish</strong> library in<br />

Europe. His 1997 Verterbukh fun loshn-koydesh-shtamike<br />

verter in yidish (Dictionary of Words of Hebrew and Aramaic<br />

Origin in <strong>Yiddish</strong>) is an invaluable tool for decoding the often<br />

difficult Hebrew spellings and sometimes surprising <strong>Yiddish</strong><br />

usages of Hebraic elements. Niborski’s <strong>Yiddish</strong>-French dictionary<br />

contains roughly 37,000 words to Weinreich’s 20,000,<br />

restoring the German and Slavic imports and introducing<br />

many dialectal forms.<br />

Niborski’s dictionary stands in Harkavy’s descriptive tradition<br />

rather than Weinreich’s normative one. The expansion of<br />

the field of <strong>Yiddish</strong> studies since Weinreich’s time made such a<br />

dictionary imperative. Scholars from many specialties now<br />

use <strong>Yiddish</strong> books and documents in their research. Serious<br />

students and translators of <strong>Yiddish</strong> fiction and poetry have<br />

been handicapped for a long time <strong>by</strong> the lack of a dictionary<br />

that draws from the full range of post-1928 literary sources.<br />

Political and social historians of Eastern European Jewry and<br />

the Holocaust need much better access to the range of dialects<br />

represented in memoirs, personal papers, and yisker-bikher<br />

(memorial books for destroyed communities). Few of these<br />

scholars are native <strong>Yiddish</strong> speakers, and the potential for misunderstanding<br />

and mistranslation is enormous.<br />

Solon Beinfeld, who is a native <strong>Yiddish</strong> speaker as well as<br />

the son of a teacher in the Workmen’s Circle schools, is a historian<br />

of modern Europe, specializing most recently in the<br />

Holocaust in the Kovno and Vilna ghettos. Based in Boston, he<br />

has made frequent research trips to the Medem, and met<br />

Niborski there. When Niborski’s dictionary appeared, Beinfeld<br />

24 SPRING 2008

told him how deeply appreciated it was in America. It would<br />

make sense, he added, given the much wider reach of English<br />

in the Jewish world, to have an English version. (“In Israel<br />

French is not a language,” an Israeli had remarked to him.)<br />

Such a version would have to be prepared, Beinfeld continued,<br />

<strong>by</strong> a native speaker of both <strong>Yiddish</strong> and English who was also<br />

fluent in French. Niborski looked at him and said, “Nu?”<br />

Thus are vocations discovered and fates sealed. Beinfeld<br />

knew that he would need collaborators with professional linguistic<br />

expertise and high-level programming skills. From his<br />

<strong>Yiddish</strong> group in the Boston area, the Khalyastre (“the Gang,”<br />

version), more words can be added at any time, and it is theoretically<br />

possible to produce dictionaries for other languages<br />

from the same database as demand and expertise arise. The<br />

English version will appear in hard copy first – a number of<br />

university presses have expressed interest – but subsequently it<br />

will be posted in full on the Web, where it can continue to<br />

expand in cyberspace as new entries are approved.<br />

The question in everyone’s mind is, When will the dictionary<br />

appear? As always, the answer depends partly on funding.<br />

Beinfeld and other retirees are donating their time, but<br />

younger contributors are not in a position to do so. After initial<br />

named for a group of avant-garde <strong>Yiddish</strong> writers in 1920s<br />

Warsaw), he drafted linguist Harry Bochner and writer Barry<br />

Goldstein, both of whom are professional programmers.<br />

Other colleagues include Michael Rosenbush, another Medem<br />

visitor who was born in Lublin and is a retired professor of<br />

Slavic languages, and project manager Elizabeth Berman.<br />

Harry Bochner has created a clear, comprehensible format<br />

for entering definitions – no easy task when dealing with two<br />

languages that read in opposite directions. The screen displays<br />

an entry with the <strong>Yiddish</strong> word, grammatical information, the<br />

French definition, and fields for entering the English definition<br />

and any comments or questions for further consideration.<br />

Once the work of the various contributors has been combined<br />

into one file <strong>by</strong> a separate program, this program allows the<br />

editor to compare the versions, word <strong>by</strong> word, and edit them as<br />

necessary for the final version.<br />

Besides the streamlining of the compilation process, the<br />

great advantage of having the dictionary in a standard computerized<br />

form (XML, for the technically minded), is that the<br />

database is infinitely expandable. The original French information<br />

is still there (though it will not appear in the English<br />

grants from the Schaechter Foundation, Yudl Mark’s <strong>Yiddish</strong>-<br />

London <strong>Yiddish</strong>ist Hirsh Perloff, and the <strong>Yiddish</strong> Groyser<br />

Hanadiv Foundation in Britain, the project<br />

received a generous grant from the<br />

verterbukh fun der<br />

Yidisher shprakh<br />

(Great Dictionary of<br />

Forward Foundation, and most recently<br />

the <strong>Yiddish</strong> Language).<br />

the David and Barbara B. Hirschhorn<br />

Foundation has contributed. The most critical stage will be the<br />

process of reconciling and editing the final entries; this really<br />

needs to be under one person’s supervision, and will need substantial<br />

and focused blocks of time. It would be a wonderful<br />

goal to finish the work in 2008, a hundred years after the<br />

Czernowitz conference, but at present it looks as if there is<br />

more than a year’s work left.<br />

The latest news on the project can be found at www.verterbukh.org,<br />

and donations can be made at www.afmedem.org.<br />

The <strong>Yiddish</strong> world will be watching with all the solicitous<br />

care, well-meaning interference, and anxious superstition<br />

with which a family watches a long-awaited pregnancy. <br />

<strong>Catherine</strong> <strong>Madsen</strong> is a contributing editor to Pakn Treger.<br />

Her most recent book is In Medias Res: Liturgy for the Estranged.<br />

25 PAKN TREGER