Floodplain hay meadows along the river Tisza in Hungary

Floodplain hay meadows along the river Tisza in Hungary

Floodplain hay meadows along the river Tisza in Hungary

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

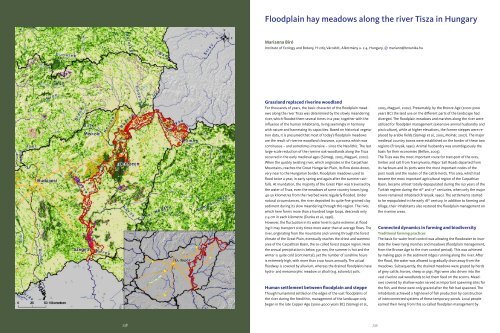

<strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Hungary</strong><br />

Marianna Biró<br />

Institute of Ecology and Botany, H-2163 Vácrátót, Alkotmány u. 2-4, <strong>Hungary</strong>, d mariann@botanika.hu<br />

Grassland replaced <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e woodland<br />

For thousands of years, <strong>the</strong> basic character of <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong><br />

<strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong> was determ<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> slowly meander<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>river</strong>, which flooded <strong>the</strong>m several times <strong>in</strong> a year, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence of <strong>the</strong> human <strong>in</strong>habitants, liv<strong>in</strong>g seem<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong> harmony<br />

with nature and harness<strong>in</strong>g its capacities. Based on historical vegetation<br />

data, it is presumed that most of today’s floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong><br />

are <strong>the</strong> result of <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e woodland clearance, a process which was<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous – and sometimes <strong>in</strong>tensive – s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> Neolithic. The last<br />

large-scale reduction of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e oak woodlands <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong><br />

occurred <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early medieval ages (Sümegi, 2005, Magyari, 2002).<br />

When <strong>the</strong> quickly twist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>river</strong>, which orig<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Carpathian<br />

Mounta<strong>in</strong>s, reaches <strong>the</strong> Great Hungarian Pla<strong>in</strong>, its flow slows down,<br />

very near to <strong>the</strong> Hungarian border. <strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>meadows</strong> used to<br />

flood twice a year, <strong>in</strong> early spr<strong>in</strong>g and aga<strong>in</strong> after <strong>the</strong> summer ra<strong>in</strong>falls.<br />

At <strong>in</strong>undation, <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> Great Pla<strong>in</strong> was traversed by<br />

<strong>the</strong> water of <strong>Tisza</strong>, even <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> of some country towns ly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

40-50 kilometres from <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>bed were regularly flooded. Under<br />

natural circumstances, <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> deposited its quite f<strong>in</strong>e-gra<strong>in</strong>ed clay<br />

sediment dur<strong>in</strong>g its slow meander<strong>in</strong>g through this region. The <strong>river</strong>,<br />

which here forms more than a hundred large loops, descends only<br />

2-4 cm <strong>in</strong> each kilometre (Dunka et al., 1996).<br />

However, <strong>the</strong> fluctuation <strong>in</strong> its water level is quite extreme: at flood<strong>in</strong>g<br />

it may transport sixty times more water than at average flows. The<br />

<strong>river</strong>, orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s and runn<strong>in</strong>g through <strong>the</strong> forest<br />

climate of <strong>the</strong> Great Pla<strong>in</strong>, eventually reaches <strong>the</strong> driest and warmest<br />

area of <strong>the</strong> Carpathian Bas<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> so-called forest steppe region. Here<br />

<strong>the</strong> annual precipitation is below 550 mm, <strong>the</strong> summer is hot and <strong>the</strong><br />

w<strong>in</strong>ter is quite cold (cont<strong>in</strong>ental), yet <strong>the</strong> number of sunsh<strong>in</strong>e hours<br />

is extremely high, with more than 2100 hours annually. The actual<br />

floodway is covered by alluvium, whereas <strong>the</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>ed floodpla<strong>in</strong>s have<br />

hydro- and mesomorphic meadow or alkali (e.g. solonetz) soils.<br />

Human settlement between floodpla<strong>in</strong> and steppe<br />

Though humank<strong>in</strong>d settled on <strong>the</strong> edges of <strong>the</strong> vast floodpla<strong>in</strong>s of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Neolithic, management of <strong>the</strong> landscape only<br />

began <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> late Copper Age (3000-4000 years BC) (Sümegi et al.,<br />

2005, Magyari, 2002). Presumably, by <strong>the</strong> Bronze Age (2000-3000<br />

years BC) <strong>the</strong> land use on <strong>the</strong> different parts of <strong>the</strong> landscape had<br />

diverged. The floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and marshes <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> were<br />

utilized for floodpla<strong>in</strong> management (extensive animal husbandry and<br />

pisciculture), while at higher elevations, <strong>the</strong> former steppes were replaced<br />

by arable fields (Sümegi et al., 2005, Molnár, 2007). The major<br />

medieval country towns were established on <strong>the</strong> border of <strong>the</strong>se two<br />

regions (Frisnyák, 1990). Animal husbandry was unambiguously <strong>the</strong><br />

basis for <strong>the</strong>ir economies (Bellon, 2003).<br />

The <strong>Tisza</strong> was <strong>the</strong> most important route for transport of <strong>the</strong> ores,<br />

timber and salt from Transylvania. Major Salt Roads departed from<br />

its harbours and its ports were <strong>the</strong> most important nodes of <strong>the</strong><br />

post roads and <strong>the</strong> routes of <strong>the</strong> cattle herds. This area, which had<br />

became <strong>the</strong> most important agricultural region of <strong>the</strong> Carpathian<br />

Bas<strong>in</strong>, became almost totally depopulated dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 150 years of <strong>the</strong><br />

Turkish regime dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 16 th and 17 th centuries, when only <strong>the</strong> major<br />

towns rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>habited (Frisnyák, 1990). The settlements started<br />

to be repopulated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 18 th century. In addition to farm<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

tillage, <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>habitants also restored <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> management on<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e areas.<br />

Connected dynamics <strong>in</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g and biodiversity<br />

Traditional farm<strong>in</strong>g practices<br />

The basis for water level control was allow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> floodwater to <strong>in</strong>undate<br />

<strong>the</strong> lower-ly<strong>in</strong>g marshes and <strong>meadows</strong> (floodpla<strong>in</strong> management,<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Bronze Age to <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> control period). This was achieved<br />

by mak<strong>in</strong>g gaps <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sediment ridges runn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>. After<br />

<strong>the</strong> flood, <strong>the</strong> water was allowed to gradually dra<strong>in</strong> away from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>meadows</strong>. Subsequently, <strong>the</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>meadows</strong> were grazed by herds<br />

of grey cattle, horses, sheep or pigs. Pigs were also driven <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong><br />

vast <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e oak woodlands to let <strong>the</strong>m feed on <strong>the</strong> acorns. Meadows<br />

covered by shallow water served as important spawn<strong>in</strong>g sites for<br />

<strong>the</strong> fish, and <strong>the</strong>se were only grazed after <strong>the</strong> fish had spawned. The<br />

<strong>in</strong>habitants achieved a high level of fish production by construction<br />

of <strong>in</strong>terconnected systems of <strong>the</strong>se temporary ponds. Local people<br />

earned <strong>the</strong>ir liv<strong>in</strong>g from this so-called floodpla<strong>in</strong> management by<br />

238 239

extensive cattle farm<strong>in</strong>g, fish<strong>in</strong>g (e.g. of <strong>the</strong> traditional species “csík”<br />

(Barbatula spp.)), catch<strong>in</strong>g crabs and also by trad<strong>in</strong>g crops and livestock<br />

(Andrásfalvy, 2007; Frisnyák, 1990).<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong> local farm<strong>in</strong>g system, transhumance also existed.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> process of extensive livestock farm<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> grey cattle were<br />

driven from <strong>the</strong> summer pastures to <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter pastures of <strong>the</strong><br />

floodpla<strong>in</strong>, which was covered by a more productive sward (Andrásfalvy,<br />

2007). Pigs, liv<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e <strong>meadows</strong> and marshes dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

summer like “semi-wild” boars, spent <strong>the</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> vast oak<br />

woodlands of <strong>the</strong> upper reaches of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>, where <strong>the</strong>y fattened<br />

on <strong>the</strong> acorns to reach <strong>the</strong>ir sell<strong>in</strong>g weight (Bellon, 2003). From <strong>the</strong><br />

neighbour<strong>in</strong>g mounta<strong>in</strong>s, large herds were also transferred to <strong>the</strong><br />

Great Pla<strong>in</strong> after <strong>the</strong> summer.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> 19 th century, <strong>the</strong> need for <strong>the</strong> expansion of<br />

arable land <strong>in</strong>creased as a result of <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>in</strong> crop prices and <strong>the</strong><br />

growth <strong>in</strong> population. This land was <strong>in</strong>itially obta<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> prevention<br />

of regular flood<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and marshes. This led to<br />

<strong>the</strong> dry<strong>in</strong>g out and rapid sal<strong>in</strong>isation of <strong>meadows</strong> <strong>in</strong> many areas. The<br />

vast dra<strong>in</strong>ed marshes and fens were ploughed. A negative effect of<br />

keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> water out of <strong>the</strong>se fields was <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease of <strong>the</strong> annual<br />

floods <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area close to <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>.<br />

Build<strong>in</strong>g high levees<br />

Moreover, because of woodland clearance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s catchments<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Great Pla<strong>in</strong> received a greater volume<br />

of water at a faster rate. To solve <strong>the</strong>se problems, high levees were<br />

built from 1884 onwards, with a f<strong>in</strong>al total length of 3000 km (Dunka<br />

et al., 1996). These embankments divided <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>to a “floodfree”<br />

area (<strong>in</strong>ner-dike area) and <strong>the</strong> “floodway”(outer-dike area),<br />

which is regularly <strong>in</strong>undated. Due to <strong>the</strong> levees be<strong>in</strong>g built close to<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>bed and <strong>the</strong> isolation of <strong>the</strong> former <strong>meadows</strong> and marshes<br />

from <strong>river</strong> floods, numerous habitats became considerably degraded<br />

and, <strong>in</strong> addition, <strong>the</strong> biodiversity of <strong>the</strong>se regions also substantially<br />

decreased. Careless alteration of land use has led to <strong>the</strong> accumulation<br />

of seem<strong>in</strong>gly unsolvable economic and social problems (Mihók et al.,<br />

2006; Rakonczay, 2002). As a result of water management, common<br />

pastures had been parcelled by <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> 19 th century and <strong>the</strong><br />

traditional transhumance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> also ceased. The<br />

extensive farm<strong>in</strong>g us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ancient grey cattle decl<strong>in</strong>ed significantly,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> “semi-wild” pig breeds also disappeared (Andrásfalvy, 2007).<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r dra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>tensification<br />

By <strong>the</strong> 1960’s, even <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>land waters on previous floodpla<strong>in</strong>s<br />

beyond <strong>the</strong> levees had been dra<strong>in</strong>ed. The arid grasslands,<br />

hav<strong>in</strong>g replaced <strong>the</strong> dried-out <strong>meadows</strong>, had been mostly ploughed<br />

by that time. This situation was worsened with <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction of<br />

<strong>the</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-crop system established on vast fields, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>creased use of chemicals and fertilizers. The replacement of <strong>the</strong><br />

floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and native woodlands with plantations of alien<br />

species (hybrids of Populus canadensis, Frax<strong>in</strong>us pennsylvanica and<br />

Acer segundo) and <strong>the</strong> establishment of large-scale cultivation on<br />

<strong>the</strong> floodway also commenced at this time. However, an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

dualism can be observed concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> utilisation of <strong>the</strong> floodway:<br />

on floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and pastures extensive, small-scale peasant<br />

farm<strong>in</strong>g (graz<strong>in</strong>g, mow<strong>in</strong>g, etc.) survived until <strong>the</strong> 1980’s, simultaneously<br />

with <strong>the</strong> socialist large-scale farm<strong>in</strong>g and forestry system. The<br />

reason was that woodlands and wooded <strong>hay</strong>fields smaller than 50<br />

ha were placed under <strong>the</strong> ownership of <strong>the</strong> farmers’ co-operatives<br />

<strong>in</strong>stead of forestry. Thus, <strong>the</strong>ir traditional, extensive utilisation may<br />

have played a significant role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> preservation of <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e species<br />

and biodiversity.<br />

Although <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second half of <strong>the</strong> 20th century most floodpla<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>meadows</strong> ly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> floodway were converted <strong>in</strong>to <strong>hay</strong>fields, grazed<br />

pastures also rema<strong>in</strong>ed until <strong>the</strong> 1980’s. The treeless grasslands, <strong>the</strong><br />

wooded pastures and <strong>hay</strong>fields and even <strong>the</strong> grass layer of <strong>the</strong> sparse<br />

woodlands, were grazed and mown. The graz<strong>in</strong>g and mow<strong>in</strong>g pattern<br />

of <strong>the</strong> grasslands was determ<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> diverse topography, <strong>the</strong><br />

water regime and <strong>the</strong> climatic conditions.<br />

Recent abandonment of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> valley<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early 1990’s <strong>the</strong> socio-economic changes (re-privatisation,<br />

decreased support for animal husbandry) considerably altered <strong>the</strong><br />

use of <strong>the</strong> floodway grasslands. Subsidisation of animal husbandry<br />

reached its m<strong>in</strong>imum level and as a consequence less milk, meat and<br />

wool was produced. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> local market system had not been developed<br />

by that time due to <strong>the</strong> previous central control, <strong>the</strong> number<br />

of livestock dramatically and rapidly decreased <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> settlements<br />

<strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>. The management of <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and wooded pastures<br />

of <strong>the</strong> floodway ceased and this has resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> slow <strong>in</strong>vasion<br />

by shrubs, which is consistent with <strong>the</strong>ir orig<strong>in</strong> from woodland<br />

clearance. At <strong>the</strong> same time, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> abandonment of <strong>the</strong><br />

pastures, <strong>the</strong> cultivation of several arable fields also ceased, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>se areas were <strong>in</strong>vaded <strong>in</strong> a few years by <strong>the</strong> previously <strong>in</strong>troduced<br />

Amorpha fruticosa. The sudden <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> amount of propagules,<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> high-level floods of <strong>the</strong> late 1990’s, led to <strong>the</strong> serious<br />

<strong>in</strong>festation of all <strong>the</strong> grasslands, wooded <strong>hay</strong>fields and woodlands.<br />

The swiftly spread<strong>in</strong>g Amorpha fruticosa destroys <strong>the</strong> natural<br />

vegetation by <strong>the</strong> deep shad<strong>in</strong>g of its dense population as well as by<br />

means of allelopathy (Szigetvári and Tóth, 2002). When <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals<br />

<strong>in</strong>vad<strong>in</strong>g a certa<strong>in</strong> area reach <strong>the</strong> age of 4-5 years, <strong>the</strong>y form a<br />

closed canopy, and <strong>the</strong> grassland becomes featureless, <strong>the</strong> character<br />

species disappear, and only species resistant to shad<strong>in</strong>g can survive.<br />

The floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> of <strong>the</strong> region<br />

Due to flood control, ancient floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>, with a nearnatural<br />

water regime and water supply can only be found with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

floodway of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>. <strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> <strong>meadows</strong> ly<strong>in</strong>g beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

levees have been ei<strong>the</strong>r cultivated or have dried out, thus <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

become sal<strong>in</strong>ified and have changed <strong>in</strong>to Achillea steppes. Accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to recent studies, floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> isolated from <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> totally<br />

dry out and become sal<strong>in</strong>ised with<strong>in</strong> 50-60 years. They are replaced<br />

by dry, short grass-dom<strong>in</strong>ated steppes typically with Achilleo-Festucetum<br />

pseudov<strong>in</strong>ae vegetation (or Lythro-Alopecuraetum <strong>in</strong> regions of<br />

lower elevation), <strong>the</strong> soil of which accumulates alkali salts at depth<br />

(Molnár and Borhidi, 2003).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Pleistocene and lower Holocene, <strong>the</strong> meander<strong>in</strong>g <strong>river</strong>s of <strong>the</strong><br />

Great Pla<strong>in</strong> deposited semi-circular po<strong>in</strong>t bars. These curved ridges<br />

can be observed on <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> anywhere <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>along</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>. The narrow depressions between <strong>the</strong>se ridges, which support<br />

marshes and sedge-dom<strong>in</strong>ated communities, usually had a direct<br />

connection with <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> <strong>in</strong> past centuries. Today, <strong>the</strong>se are covered<br />

by smaller or wider patches of marsh vegetation dom<strong>in</strong>ated by<br />

Glyceria maxima or Phalaris arund<strong>in</strong>acea large sedges such as Carex<br />

gracilis, and beds of Phragmites australis or Typha latifolia. The top of<br />

<strong>the</strong> curved ridges are covered by Peucedanum offic<strong>in</strong>ale dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

meadow-steppes, while on <strong>the</strong>ir slopes and at lower elevations, tall<br />

herb communities and different types of marshes have established.<br />

The <strong>meadows</strong> have properly adapted to <strong>the</strong> rapidly chang<strong>in</strong>g water<br />

supply and, with <strong>the</strong>ir dynamically chang<strong>in</strong>g species composition,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y tolerate both <strong>the</strong> longer humid and dry periods. Nowadays,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are partially under nature conservation management, and <strong>the</strong><br />

authorities try to susta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir current state by mechanized mow<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Under natural conditions, with <strong>the</strong> cessation of mow<strong>in</strong>g or graz<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

<strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> are slowly encroached by <strong>the</strong> native <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e<br />

trees (Salix alba, S. fragilis, S. purpurea, Populus alba, P. nigra, Quercus<br />

robur, Frax<strong>in</strong>us angustifolia ssp. pannonica, Ulmus campestris and U.<br />

laevis) or shrubs (Viburnum opulus, Euonymus europaeus, Sambucus<br />

nigra and Crataegus monogyna), as <strong>the</strong>y orig<strong>in</strong>ated from <strong>the</strong> cleared<br />

woodlands. This tendency was utilised by humank<strong>in</strong>d with <strong>the</strong> development<br />

of wooded pastures and <strong>hay</strong>fields, where some young trees<br />

were left to grow, establish<strong>in</strong>g a special landscape characteristic of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong>. Due to <strong>the</strong> cessation of management, <strong>the</strong> condition<br />

of <strong>the</strong> wooded pastures and <strong>hay</strong>fields gradually decl<strong>in</strong>ed and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are replaced by thickets of <strong>in</strong>troduced species over a relatively<br />

short period of time. Though <strong>the</strong>y have great value as examples of<br />

traditional land-use support<strong>in</strong>g high biodiversity, <strong>the</strong>ir preservation<br />

on <strong>the</strong> non-protected areas has not as yet been resolved.<br />

<strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> mesotrophic <strong>meadows</strong><br />

<strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> mesotrophic <strong>meadows</strong> were once <strong>the</strong> most frequent<br />

meadow type <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>. Even today <strong>the</strong>y serve as a matrix for<br />

<strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>. Under natural conditions, <strong>the</strong>y are wet<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> greater part of <strong>the</strong> year, and often <strong>in</strong>undated. They are<br />

characterised by meadow and marsh species and dom<strong>in</strong>ated by Alopecurus<br />

pratensis, Poa pratensis, Festuca pratensis, Dactylis glomerata<br />

and Carex melanostachya. The average height of <strong>the</strong> sward is about<br />

0,5-1 metre and species composition is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> duration<br />

of water cover. The characteristic species are Clematis <strong>in</strong>tegrifolia,<br />

Galium rubioides, Cardam<strong>in</strong>e pratensis, Galega offic<strong>in</strong>alis, Gratiola offic<strong>in</strong>alis,<br />

Viola elatior, Rumex confertus, Thalictrum flavum, Thalictrum<br />

lucidum, Cirsium canum, Cichorium <strong>in</strong>tibus, Symphytum offic<strong>in</strong>ale, Iris<br />

pseudacorus, Galium palustre, Lysimachia vulgaris, Lythrum virgatum,<br />

L. salicaria, Ranunculus repens, Past<strong>in</strong>aca sativa and Lychnis flos-cucculi.<br />

Sometimes <strong>the</strong>y may have fen characteristics due to water logg<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

This is <strong>in</strong>dicated by <strong>the</strong> presence of species such as Serratula t<strong>in</strong>ctoria,<br />

Ophioglossum vulgatum and Gentiana pneumonan<strong>the</strong>. In <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>,<br />

<strong>the</strong> characteristic colourful species <strong>in</strong>clude those that are often also<br />

typical of <strong>the</strong> willow-poplar woodlands, such as Leucojum aestivum.<br />

240<br />

241

Meadow-steppes<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>, <strong>the</strong> grasslands of <strong>the</strong> highest nature<br />

conservation value are <strong>the</strong> meadow-steppes, established on <strong>the</strong> top<br />

of <strong>the</strong> curved ridges. Today, each of <strong>the</strong>ir stands can be considered<br />

as curiosities. They survive <strong>in</strong> a few places and only a small area<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s, as <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong>m were cultivated due to favourable<br />

site conditions. The term “meadow-steppe” refers to <strong>the</strong>ir species<br />

composition, conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g species of both <strong>meadows</strong> and steppes.<br />

The dom<strong>in</strong>ance of <strong>the</strong> species changes dynamically <strong>in</strong> response to<br />

<strong>the</strong> humid and dry periods. Dry years favour <strong>the</strong> spread of steppe<br />

elements, while <strong>the</strong>se are replaced by meadow species <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> more<br />

humid periods. Under natural conditions, <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e meadow-steppes<br />

were rarely flooded. The characteristic species are Peucedanum offic<strong>in</strong>ale,<br />

Iris spuria, Aster punctatus and Aster l<strong>in</strong>osyris. Steppe elements<br />

are Filipendula vulgaris, Asparagus offic<strong>in</strong>alis, Hypericum perforatum,<br />

Fragaria viridis, Artemisia pontica and V<strong>in</strong>cetoxicum hirund<strong>in</strong>aria.<br />

Dom<strong>in</strong>ant grasses of this community are Festuca pseudov<strong>in</strong>a, Festuca<br />

rupicola, Poa pratensis, Poa angustifolia and Carex praecox. A rare<br />

grass of meadow-steppe is Hierochloe odorata. Sal<strong>in</strong>e forest steppe<br />

<strong>meadows</strong> with tall herbs (Peucedano-Asteretum), which are related to<br />

<strong>the</strong> cool cont<strong>in</strong>ental <strong>meadows</strong> of South-Siberia, also belong to <strong>the</strong><br />

category of floodpla<strong>in</strong> meadow-steppes (Borhidi and Sánta, 1999).<br />

<strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> tall herb communities<br />

Typical transitional communities of <strong>the</strong> <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> on <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

bars are <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> tall herb communities, hav<strong>in</strong>g established<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>cipally on <strong>the</strong> verges of <strong>the</strong> lower ly<strong>in</strong>g marshes and <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>s<br />

of scrubs and groves. On <strong>the</strong> humidity gradient, this habitat of<br />

great conservation value lies between <strong>the</strong> marshes and <strong>meadows</strong>. If<br />

mow<strong>in</strong>g is abandoned for a long period, monocotyledons and marsh<br />

species tend to become dom<strong>in</strong>ant, while regular mow<strong>in</strong>g and burn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

transforms this vegetation type <strong>in</strong>to mesotrophic floodpla<strong>in</strong><br />

meadow. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to our present knowledge, <strong>the</strong> survival of this<br />

vegetation is ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed by episodic management. An example<br />

of its vulnerability is if mow<strong>in</strong>g ceases– even for a few years, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

degradation occurs rapidly due to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasion of Calamagrostis epigeios<br />

and Amoropha fruticosa. Characteristic of this vegetation is <strong>the</strong><br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ance of tall herbs, <strong>the</strong>y form stands of 1-1.5 metres <strong>in</strong> height.<br />

The most characteristic species are <strong>the</strong> Ponto-Pannonian Leucan<strong>the</strong>mella<br />

serot<strong>in</strong>a, <strong>the</strong> endemic Pannonian Armoratia macrocarpa, as<br />

well as Veronica longifolia, Senecio paludosus, Euphorbia lucida and E.<br />

palustris, Thalictrum lucidum and flavum, and Betonica offic<strong>in</strong>alis. Fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

frequent species <strong>in</strong>clude Althaea rosea, Epilobium hirsutum, Lysimachia<br />

vulgaris, Lythrum virgatum, L. salicaria, Stachys palustris and<br />

Symphytum offic<strong>in</strong>ale. In addition, species typical of Phalaris arund<strong>in</strong>acea<br />

beds, reed beds and sedge beds such as Phalaris arund<strong>in</strong>acea,<br />

Calamagrostis pseudophragmites, Carex gracilis, C. acutiformis, Phragmites<br />

australis and Iris pseudacorus may also occur <strong>in</strong> this community.<br />

The dom<strong>in</strong>ant grasses of <strong>the</strong> mesotrophic <strong>meadows</strong> (Alopecurus<br />

pratensis, Agrostis stolonifera and Poa pratensis) are sub-ord<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

among <strong>the</strong> tufts and clones of tall herbs and marsh species. Depend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on land use, sub-dom<strong>in</strong>ant Galium rubioides, G. palustre and Viola<br />

elatior and rarely Poa palustris, Stellaria palustris, Leersia oryzoides and<br />

Lathyrus palustris may also be a component of <strong>the</strong> species pool.<br />

Floristic elements of floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong><br />

Table 1 summarises <strong>the</strong> abundance, <strong>the</strong> “floral element” type and <strong>the</strong><br />

habitat preference of <strong>the</strong> most typical species of floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong><br />

and is based on Horváth et al., 1995 and Király, 2007. More than half<br />

of <strong>the</strong> listed species are Eurasian or Cont<strong>in</strong>ental, some are Pontic<br />

or Pontic Cont<strong>in</strong>ental, while one is Eurosiberian. South-eastern European<br />

and Mediterranean species are also a component of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

<strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>. Among <strong>the</strong> species listed <strong>in</strong> table 1, <strong>the</strong> most valuable<br />

ones are Armoracia macrocarpa, endemic <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Carpathian Bas<strong>in</strong> and<br />

Peucedanum offic<strong>in</strong>ale, which is a typical species of Central European<br />

moist wood-steppe. Though most listed species are characteristic<br />

of Phragmition or Mol<strong>in</strong>io-Arrhena<strong>the</strong>rea, some of <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong>dicate fen<br />

character <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> habitats, such as Senecio paludosus, Serratula t<strong>in</strong>ctoria,<br />

Ophioglossum vulgatum and Gentiana pneumonan<strong>the</strong>.<br />

Aspects of fauna<br />

Before <strong>the</strong>ir dra<strong>in</strong>age, <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>, flooded annually<br />

by <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>, were <strong>the</strong> most important spawn<strong>in</strong>g grounds <strong>in</strong><br />

Middle Europe. Rema<strong>in</strong>s of ancient tools and written records serve<br />

as evidence for <strong>the</strong> fact that fish ponds were already established on<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> before <strong>the</strong> foundation of <strong>the</strong> Hungarian state. These<br />

ponds were utilised with admirable success by <strong>the</strong> descendants of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Scythians (Andrásfalvy, 2007; Molnár, 2003). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong><br />

medieval records, fish of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>, packed among ice and <strong>hay</strong>, were<br />

transported to Wien, or even to <strong>the</strong> markets of Paris. Nowadays,<br />

spawn<strong>in</strong>g by fish – pr<strong>in</strong>cipally <strong>the</strong> common carp (Cypr<strong>in</strong>us carpio) – is<br />

possible only on a few floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>. Thus, <strong>the</strong> former abundance<br />

of fish has also decreased considerably.<br />

Mosquitoes, day-flies, dragon-flies, caddis-flies and beetles, breed <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> water conf<strong>in</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> of <strong>the</strong> floodway. These are a rich<br />

source of food for <strong>the</strong> reptiles, amphibians of this habitat and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

also serve as prey for hunt<strong>in</strong>g bats, e.g. Myotis daubentonii and <strong>the</strong><br />

rare Myotis dasycneme (Lisztes, 2004). These animals all attract <strong>the</strong><br />

birds that nest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> gnarled trees of <strong>the</strong> neighbour<strong>in</strong>g woodlands,<br />

reed beds or scrub. Thus, <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> are often visited by Ciconia<br />

ciconia, C. nigra, Ardea c<strong>in</strong>erea, A. purpurea, Botaurus stellaris, Nycticorax<br />

nycticorax or ibises, such as <strong>the</strong> impressive Platalea leucorodia,<br />

Egretta alba, Egretta garzetta and <strong>the</strong> very rare Plegadis falc<strong>in</strong>ellus.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>sects of <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> are also food for Hirundo rustica, Coracias<br />

garrulus, Falco verpert<strong>in</strong>us and F. t<strong>in</strong>nunculus, Locustella fluviatilis,<br />

Hypollais pallida, Lanius collurio and Saxicola rubetra. Birds of prey,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g owls, which live <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e woodlands and hunt on <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>meadows</strong>, are real specialities of <strong>the</strong>se regions of <strong>the</strong> Great Pla<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>. Such birds are Haliaetus albicilla, Milvus migrans,<br />

Circus aerug<strong>in</strong>osus, Falco subbuteo, Falco cherrug and Asio otus (Varga,<br />

2002; Fekete and Varga, 2006). The most important ground-nest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

birds are Vanellus vanellus, Perdix perdix and Crex crex. The latter species<br />

which nests among <strong>the</strong> tall herbs, now receives special protection<br />

due to its rarity.<br />

Ow<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> regular flood<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>, habitats <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong><br />

collectively form an ecological corridor of outstand<strong>in</strong>g importance,<br />

which is demonstrated by <strong>the</strong> downward dispersion of <strong>the</strong> fauna<br />

from <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s (e.g. <strong>the</strong> Transylvanian grasshoppers, like Leptophyes<br />

discoidalis and Poecilimon schmidtii). The most <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>sects of floodpla<strong>in</strong> mesotrophic <strong>meadows</strong> and Peucedanum offic<strong>in</strong>ale-dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

meadow-steppes are <strong>the</strong> species that have a cool<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ental, Euro-Siberian distribution, while <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> lower course<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn, sub-Mediterranean species occur here at <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost limits of <strong>the</strong>ir range. The most frequent Orthopteras<br />

are Mantis religiosa, Conocephalus and Ruspolia spp., Gampsocleis glabra,<br />

Chrysochraon dispar, Pezotettix giornae, Mecostethus grossus and<br />

Polysarcus denticauda, a characteristic species of <strong>the</strong> sub-montane<br />

<strong>meadows</strong> (Varga, 2002). This region is <strong>the</strong> westernmost part of <strong>the</strong><br />

distribution range of <strong>the</strong> sub-endemic Odontopodissima rubripes.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Carpathian Bas<strong>in</strong>, Gortyna borelli ssp. lunata, which receives<br />

special protection, only feeds on Peucedanum offic<strong>in</strong>ale, while Thalictrum<br />

species are <strong>the</strong> larval food plants of Lamprotes aureum. The<br />

phylogenetically quite ancient Zerynthia polyxena, which reaches <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn and western edges of its range <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Carpathian Bas<strong>in</strong>, is<br />

monophagous on Aristolochia clematitis, a frequent character plant<br />

species of <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> (Varga, 2002). Some o<strong>the</strong>r rare,<br />

protected and impressive butterflies are Lycaena dispar, Papilio machaon<br />

and Vanessa atalanta.<br />

Future and possible way forward<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> flood control, <strong>the</strong> habitats represent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> past<br />

natural vegetation of <strong>the</strong> ancient <strong>Tisza</strong> district have become concentrated<br />

<strong>in</strong> a ra<strong>the</strong>r small area, toge<strong>the</strong>r with those parts that constitute<br />

<strong>the</strong> new, secondary landscape, which established as a result of<br />

<strong>the</strong> control. In <strong>the</strong> floodway, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> flood regulation, <strong>the</strong> area of<br />

grasslands has been substantially reduced, while <strong>the</strong> proportion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> woodlands has <strong>in</strong>creased. Moreover, <strong>in</strong>troduced tree and shrub<br />

species have also appeared (Molnár, 2007).<br />

Problems with alien species<br />

Some of <strong>the</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> of great natural value<br />

are under conservation management. Although <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

district of <strong>the</strong> three National Parks are annually mown, <strong>the</strong> clearance<br />

of some areas <strong>in</strong>vaded by Amorpha fruticosa has still to be tackled.<br />

This process, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> restoration of <strong>the</strong> floodpla<strong>in</strong>s, <strong>the</strong><br />

traditional land use and <strong>the</strong> reconstruction of <strong>the</strong> previous landscape,<br />

is supported by national and <strong>in</strong>ternational grants (like LIFE).<br />

Experiments have been conducted at controll<strong>in</strong>g Amorpha fruticosa<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g grey cattle to graze <strong>the</strong> affected <strong>meadows</strong>. Nowadays, nonprotected<br />

grasslands owned by smallholders are mostly grazed by<br />

cattle or sheep, although some have been gradually abandoned. Almost<br />

none are regularly mown or burnt. Due to a lack of money, <strong>the</strong><br />

owners do not clear Amorpha fruticosa from <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

previously valuable <strong>hay</strong>fields and wooded pastures are relatively<br />

quickly <strong>in</strong>vaded by shrubs.<br />

The cont<strong>in</strong>uous alterations of <strong>the</strong> landscape, as a consequence of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> control, have led to unprecedented environmental change.<br />

This has had an impact on <strong>the</strong> competition between <strong>the</strong> species<br />

242<br />

243

and has caused <strong>the</strong> loss of a number of habitats. The value of <strong>the</strong><br />

landscape is vanish<strong>in</strong>g even more seriously before our very eyes. The<br />

heterogeneity and dynamism of <strong>the</strong> landscape, mentioned <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

previous section, implies that land use will significantly determ<strong>in</strong>e<br />

<strong>the</strong> dest<strong>in</strong>y of this region <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future, just as it did <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past. If <strong>the</strong><br />

grasslands are not mown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future and <strong>the</strong> shrubs <strong>in</strong>vad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m<br />

are not cleared from <strong>the</strong>se areas, <strong>the</strong> grasslands will be replaced by<br />

<strong>the</strong> spontaneously extend<strong>in</strong>g thickets of Amorpha fruticosa. The vast<br />

majority of grasslands will disappear, and most of <strong>the</strong>ir species will<br />

vanish as a result of allelopathy and shad<strong>in</strong>g by Amorpha fruticosa. It<br />

is likely that o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>troduced woody species will also appear, such<br />

as Frax<strong>in</strong>us pennsylvanica and Acer negundo and lianas. In about 20-30<br />

years, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasion of trees and lianas will transform <strong>the</strong> former <strong>hay</strong>fields<br />

and wooded <strong>hay</strong>fields <strong>in</strong>to dense <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e thickets dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

by non-native species. The effects of <strong>the</strong> eradication of Amorpha<br />

Table 1. Characteristics of typical species of floodpla<strong>in</strong> <strong>meadows</strong>.<br />

Typical species<br />

Abundance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Tisza</strong>-valley<br />

IUCN<br />

Categories 2001<br />

Near Threatened<br />

Flora element<br />

fruticosa thickets and <strong>the</strong> mow<strong>in</strong>g of grasslands can be determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

unambiguously <strong>in</strong> advance (Szigetvári and Tóth 2005). The traditional<br />

forms of landscape management have had a long history of<br />

practice <strong>in</strong> <strong>Hungary</strong> with accurately developed methods. Thus <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

precise application might be a suitable approach for <strong>the</strong> future. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y cannot be applied even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> most valuable regions due<br />

to a lack of money.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ancial support<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ancial support and regulation measures of <strong>the</strong> European Union,<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> subsidisation of agrarian nature conservation, <strong>the</strong> support<br />

for <strong>the</strong> development of ecotourism and <strong>the</strong> Environmentally Sensitive<br />

Areas program, are of great importance for preserv<strong>in</strong>g small-scale<br />

peasant farm<strong>in</strong>g and traditional forms of land use. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>habitants of this region reluctantly cont<strong>in</strong>ue to reduce <strong>the</strong> number<br />

Habitat preference<br />

Armoracia macrocarpa rare NT Pannonian Endemic Phragmition australis<br />

Artemisia pontica common - Eurasian - Mediterranean Festucetalia valesiaceae & Artemisio -<br />

Festucetalia pseudov<strong>in</strong>ae<br />

Aster sedifolius frequent - Eurasian - Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Artemisio - Festucetalia pseudov<strong>in</strong>ae<br />

Cardam<strong>in</strong>e pratensis loc. frequent - Circumpolar Mol<strong>in</strong>io - Arrhena<strong>the</strong>rea<br />

Centaurea pannonica common - South-East European Mol<strong>in</strong>io - Arrhena<strong>the</strong>rea<br />

Clematis <strong>in</strong>tegrifolia rare - Eurasian - Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Mol<strong>in</strong>io - Arrhena<strong>the</strong>rea<br />

Eryngium planum rare - Pontic Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Agrostion albae<br />

Euphorbia palustris common - European Magnocaricion<br />

Galium rubioides common - Central European Alopecurion pratensis<br />

Gentiana pneumona<strong>the</strong> rare NT Eurasian Mol<strong>in</strong>io-Juncetea<br />

Iris spuria rare NT West-Mediterranean Mol<strong>in</strong>ietalia<br />

Lathyrus palustris rare NT Circumpolar Phragmitetea & Mol<strong>in</strong>io-Juncetea<br />

Leucan<strong>the</strong>mella serot<strong>in</strong>a loc. frequent NT Cont<strong>in</strong>ental – Pontic Pannonian Phragmition australis<br />

Leucojum aestivum loc. frequent NT Sub-Atlantic - Submediterranean Salicion albae<br />

Peucedanum offic<strong>in</strong>ale frequent NT Central European Cynodonto-Festucion & Aceri tatarico-Quercion<br />

Poa palustris rare - Circumpolar Phragmitetea & Mol<strong>in</strong>io-Juncetea<br />

Rumex confertus loc. frequent NT Eurosiberian Alopecurion pratensis<br />

Scutellaria galericulata common - Circumpolar Phragmitetea & Mol<strong>in</strong>io-Juncetea<br />

Senecio paludosus rare NT Eurasian - Mediterranean Caricion rostratae & Magnocaricion<br />

Serratula t<strong>in</strong>ctoria rare - European - Mediterranean Mol<strong>in</strong>io - Arrhena<strong>the</strong>rea<br />

Thalictrum flavum common - Eurasian Mol<strong>in</strong>ietalia & Magnocaricion<br />

Thalictrum lucidum common - Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Mol<strong>in</strong>ietalia<br />

Veronica longifolia common - Eurasian Agrostion albae<br />

Viola elatior loc. frequent - Eurasian Alno-Padion<br />

Viola pumila loc. frequent NT Pontic Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Deschampsion caespitosae<br />

of livestock, and unfortunately, <strong>the</strong>y are often not <strong>in</strong>formed about<br />

what land management options may be available, or <strong>the</strong>y are unable<br />

to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> aid of <strong>the</strong> government or <strong>the</strong> European Union.<br />

In some parts of <strong>the</strong> region, so extremely severe is <strong>the</strong> level of<br />

poverty that people choose to travel to <strong>the</strong> distant but far cheaper<br />

hypermarkets, while <strong>the</strong> use of shops and services <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> smaller<br />

settlements is alarm<strong>in</strong>gly reduced. The local (ma<strong>in</strong>ly bio-)products<br />

of higher quality are very expensive so that with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region, only<br />

eco-tourists can afford to buy <strong>the</strong>m, and <strong>the</strong>se products can only be<br />

sold <strong>in</strong> distant parts of <strong>the</strong> country. See<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lack of job possibilities,<br />

markets and even schools, more and more people tend to move<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> towns. Thus, it is very important to provide f<strong>in</strong>ancial support<br />

for local food production and <strong>the</strong> trade of local products <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

reta<strong>in</strong> people <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> villages of <strong>the</strong> district.<br />

EU directives, such as <strong>the</strong> Water Framework Directive, help to preserve<br />

<strong>the</strong> waters of <strong>the</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>age bas<strong>in</strong> and wetlands of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>, at<br />

least <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir current state. This regulation system plays an essential<br />

role <strong>in</strong> controll<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> water quality, annually flood<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>meadows</strong><br />

and also <strong>in</strong> susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ponds. However, it may also concern<br />

conceptual questions, such as <strong>the</strong> planned dredg<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong>bed<br />

aimed at mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong> navigable. This might have disastrous<br />

effects on both <strong>the</strong> wildlife of <strong>the</strong> <strong>river</strong> and <strong>the</strong> water regime of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>meadows</strong> with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> floodway.<br />

With its special cuis<strong>in</strong>e and still fish<strong>in</strong>g waters, <strong>the</strong> marvellous and<br />

diverse, but at <strong>the</strong> same time, very calm landscape of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>, has,<br />

for a long time, been a magnet for tourists. Restor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> system of<br />

<strong>the</strong> medieval fish<strong>in</strong>g ponds would provide new opportunities for ecotourism.<br />

This would also mean a chance to reconstruct <strong>the</strong> temporarily<br />

flooded <strong>river</strong><strong>in</strong>e <strong>hay</strong> <strong>meadows</strong> and marshes, on <strong>the</strong> grounds of<br />

<strong>the</strong> EU support. The aforementioned traditional fish<strong>in</strong>g ponds, fill<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with water each year at <strong>in</strong>undation, would give rise to a prosperous<br />

pisciculture. Moreover, <strong>the</strong>y would also reduce <strong>the</strong> damage caused<br />

by <strong>the</strong> floods, which are becom<strong>in</strong>g more and more frequent.<br />

references<br />

Andrásfalvy B. 2007. A Duna mente népének ártéri gazdálkodása. (Historical floodpla<strong>in</strong><br />

management <strong>along</strong> <strong>the</strong> Danube, <strong>Hungary</strong>) Ekvilibrum Kiadó, Budapest.<br />

Bellon T. 2003. A <strong>Tisza</strong> néprajza. Ártéri gazdálkodás a <strong>Tisza</strong>i Alföldön. (The Ethnography<br />

of <strong>Tisza</strong>. <strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> management on <strong>the</strong> Hungarian Pla<strong>in</strong>) Timp Kiadó, Budapest.<br />

Borhidi A., Sánta A. (Eds.) 1999. Vöröskönyv Magyarország növénytársulásairól I.<br />

(Redbook of <strong>the</strong> Hungarian vegetation I.) TermészetBúvár Alapítvány Kiadó, Budapest.<br />

Dunka S., Fejér L., Vágás I. 1996. A verítékes honfoglalás. A <strong>Tisza</strong>-szabályozás története.<br />

(The history of <strong>Tisza</strong> <strong>river</strong>control) KHVM, Budapest.<br />

Fekete G. and Varga Z. (Eds.) 2006. Magyarország tája<strong>in</strong>ak növényzete és állatvilága.<br />

(Vegetation and fauna of <strong>Hungary</strong>) Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest.<br />

Frisnyák S. 1990. Magyarország történeti földrajza. (Historical geography of <strong>Hungary</strong>)<br />

Tankönyvkiadó, Budapest.<br />

Horváth F. et al. 1995. Flóra adatbázis 1.2. Taxonlista és attributum állomány. (Flora<br />

database of <strong>Hungary</strong>, taxonlists and attributs) Institute of Ecology and Botany of <strong>the</strong><br />

Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Vácrátót.<br />

Király G. 2007. Vörös Lista. (Red list of vascular flora of <strong>Hungary</strong>). University of Sopron,<br />

Sopron.<br />

Lisztes J. 2004. Szikra és az Alpári-rét. (Szikra and <strong>the</strong> Alpár-meadow) Boróka Füzetek.<br />

Kiskunság National Park, Kecskemét.<br />

Magyari E. 2002. Climatic versus human modification of <strong>the</strong> Late Quaternary vegetation<br />

<strong>in</strong> Eastern <strong>Hungary</strong>, Ph.D. <strong>the</strong>sis, University of Debrecen.<br />

Mihók B. et al. 2006. The status of <strong>the</strong> South-Borsod <strong>Floodpla<strong>in</strong></strong> from <strong>the</strong> viewpo<strong>in</strong>t<br />

of local people and ecologists. An <strong>in</strong>terdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary research on traditional ecological<br />

knowledge (TEK). – Természetvédelmi Közlemények 12, 79-103.<br />

Molnár G. 2003. A Tiszánál. (By <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong>) Ekvilibrium Kiadó, Budapest.<br />

Molnár Zs. 2007. Történeti tájökológiai kutatások az Alföldön. (Historical landscape<br />

ecological resources on <strong>the</strong> Hungarian Great Pla<strong>in</strong>), Ph.D. <strong>the</strong>sis, University of Pécs.<br />

Molnár Zs. and Borhidi A. 2003. Cont<strong>in</strong>ental alkali vegetation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Hungary</strong>. syntaxonomy,<br />

landscape history, vegetation dynamics, and conservation. Phytocoenologia 21, 235-245.<br />

Rakonczai J. 2002. A <strong>Tisza</strong> vízgyűjtője, m<strong>in</strong>t komplex vizsgálati és fejlesztési régió.<br />

(The waterbase of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Tisza</strong> as a comlex study and development area). <strong>Tisza</strong> Vízgyűjtő<br />

Programrégió, Szeged.<br />

Sümegi P. 2005. Loess and Upper Paleolithic environment <strong>in</strong> <strong>Hungary</strong>. Aurea Kiadó,<br />

Nagykovácsi.<br />

Sümegi P., Csökmei B., Persaits G. 2005. The evolution of Polgár Island, A loess-covered<br />

lag surface and its <strong>in</strong>fluences on he subsistence of settl<strong>in</strong>g human cultural groups, <strong>in</strong>:<br />

Hum L., Gulyás S., Sümegi P. (Eds.). Environmental Historical Studies from <strong>the</strong> Late<br />

Tertiary and Quaternary of <strong>Hungary</strong>. University of Szeged, Szeged, 141-163.<br />

Szigetvári Cs. and Tóth T. 2002. A gyalogakác. (The Amorpha fruticosa), <strong>in</strong>: Botta-Dukát<br />

Zoltán (Ed.). Az <strong>in</strong>váziós növényfajok magyarországi terjedése és visszaszorításuk<br />

természetvédelmi stratégiája (Alien species <strong>in</strong> <strong>Hungary</strong>). TermészetBÚVÁR Alapítvány<br />

Kiadó, Budapest.<br />

Varga Z. 2002. Ők élnek Pannóniában. (They live <strong>in</strong> <strong>Hungary</strong>) Well-Press Kiadó, Miskolc.<br />

Király G. 2007. Vörös Lista. (Red list of vascular flora of <strong>Hungary</strong>). University of Sopron,<br />

Sopron.<br />

244 245