Chapter 3 Reading the Rocks - Saudi Aramco

Chapter 3 Reading the Rocks - Saudi Aramco

Chapter 3 Reading the Rocks - Saudi Aramco

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

72 energy to <strong>the</strong> world : Volume one<br />

reading <strong>the</strong> rocks 73<br />

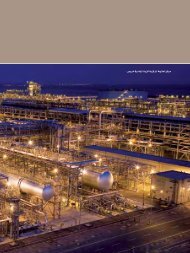

golden corridor<br />

More than 60 percent of <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

proven crude oil reserves and 40 percent<br />

of proven natural gas reserves lie in a<br />

2,700-kilometer-long swath of <strong>the</strong> Middle<br />

East, which runs from eastern Turkey<br />

down through <strong>the</strong> Arabian Gulf to <strong>the</strong><br />

Arabian Sea.<br />

senior Socal geologist, Max Steineke. Steineke, who had graduated from Stanford University in<br />

1921 and had spent <strong>the</strong> previous 13 years working for Socal in a variety of remote locations, had<br />

asked to be transferred to <strong>the</strong> new operation in <strong>Saudi</strong> Arabia. He joined <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r geologists in<br />

Bahrain, where <strong>the</strong>y met to be ferried over to Jubail. Steineke was to lead a new third team of<br />

geologists in <strong>the</strong> field.<br />

Steineke’s colleagues soon recognized his acumen in understanding <strong>the</strong> sort of big-picture geology<br />

that was called for in exploring <strong>the</strong> huge concession. He was also a natural outdoorsman and expert<br />

marksman, which helped him earn <strong>the</strong> respect of <strong>the</strong> Bedouin soldiers and guides who accompanied<br />

<strong>the</strong> geological parties in <strong>the</strong> field. He was a rough-and-tumble “man’s man” with a face as wea<strong>the</strong>red<br />

as a limestone outcropping, and hardly a stickler for details or a fancier of civilized ways.<br />

Steineke doggedly pursued evidence of a geological trend that might as well have been<br />

invisible as far as many of <strong>the</strong> geologists were concerned. Philip McConnell, who joined <strong>the</strong><br />

production crews in <strong>Saudi</strong> Arabia in 1938, recalled that “Steineke knew <strong>the</strong> outlines of <strong>the</strong> great<br />

[al-Na‘lah or En Nala, as it was listed in geological records] anticline (<strong>the</strong> ‘Ghawar’ field) very early,<br />

and knew it might be one of <strong>the</strong> mightiest oil traps in <strong>the</strong> world. But he had a lot of German<br />

caution, almost to a fault—refused to commit himself in judgment until pushed.”<br />

Indeed, as early as <strong>the</strong> end of his first season in <strong>the</strong> field (spring 1935), Steineke and his<br />

partner, Tom Koch, had seen tantalizing hints in <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> concession area of what turned<br />

out to be <strong>the</strong> biggest oil field ever discovered—not just in <strong>Saudi</strong> Arabia but anywhere. “They<br />

described four o<strong>the</strong>r … highlands areas, at least one of which was definitely domed,” Casoc<br />

company records state, on which <strong>the</strong>y said fur<strong>the</strong>r work would be justified, but only if drilling<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Dammam Dome found oil in commercial quantities.<br />

mediterranean<br />

sea<br />

jordan<br />

iraq<br />

caspian<br />

sea<br />

While <strong>the</strong>ir recommendations for continued work in <strong>the</strong> region zeroed in on areas and<br />

structures that eventually were recognized as overlying <strong>the</strong> giant oil fields of Abqaiq, Qatif and<br />

Ghawar, marking a structure as worthy of study is far from finding firm evidence of oil. It took at<br />

least 15 years before company geologists fully appreciated <strong>the</strong> underground structures hinted at<br />

by <strong>the</strong> surface features Steineke and Koch identified and marked for fur<strong>the</strong>r study in <strong>the</strong> spring<br />

of 1935 on <strong>the</strong>ir “to-do” list:<br />

1. Drill a test on <strong>the</strong> El ‘Alat Dome.<br />

2. Map Edh Duraiya, el Abqaiq and Qurain in detail.<br />

3. Drill core holes or carry a seismograph survey across Tarut Island.<br />

4. Investigate <strong>the</strong> highland southwest of Abqaiq.<br />

5. Follow <strong>the</strong> En Nala monoclinal fold, lying west of Hofuf to <strong>the</strong> south and northwest<br />

to determine its origin.<br />

6. Investigate <strong>the</strong> Ghawar area, lying west of Hofuf.<br />

7. Introduce subsurface means of investigation to give geological information beneath<br />

<strong>the</strong> sand areas and <strong>the</strong> overlapping Miocene in certain localities.<br />

Casoc geologists Max Steineke and<br />

Bert Miller, drilling foreman Guy<br />

“Slim” Williams, construction foreman<br />

Walt Haenggi, left to right, and three<br />

unidentified colleagues pause as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y look for <strong>the</strong> best site for <strong>the</strong> first<br />

well on <strong>the</strong> Dammam Dome. The well<br />

was “spudded” on April 30, 1935.<br />

key<br />

golden corridor<br />

Gas field<br />

oil field<br />

r e d s e a<br />

kuwait<br />

saudi arabia<br />

yemen<br />

united arab<br />

emirates<br />

a r a b<br />

g u l f o f o m a n<br />

oman<br />

i a n s e a<br />

Focusing on Dammam With geologists in <strong>the</strong> field and at headquarters in San Francisco agreeing<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Dammam Dome was <strong>the</strong> most promising site for drilling, plans for moving drilling<br />

materials and crews into <strong>Saudi</strong> Arabia began by late September 1934. With some pride, company<br />

officials noted <strong>the</strong> date <strong>the</strong>y formally notified King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz of <strong>the</strong>ir drilling plans—only one<br />

year to <strong>the</strong> day after <strong>the</strong> first geologists had splashed ashore in <strong>Saudi</strong> Arabia.<br />

Mobilizing for <strong>the</strong> drilling program was not just a question of floating a rig across <strong>the</strong> Gulf<br />

from Bahrain and <strong>the</strong>n hauling it through <strong>the</strong> sand and salt flats to <strong>the</strong> Dammam Dome site, as<br />

formidable as those challenges proved to be. Fred Davies, acting foreman of Bapco operations in<br />

Bahrain at <strong>the</strong> time, argued that <strong>the</strong> isolation of <strong>the</strong> site and <strong>the</strong> extreme summer heat required<br />

that <strong>the</strong> company undertake a dramatic housing program—a small town in <strong>the</strong> desert—far<br />

more elaborate than <strong>the</strong> bare minimum that might be <strong>the</strong> norm for such camp facilities. The<br />

initial community was to consist of living quarters, a cookhouse, a mess hall and a recreation<br />

room. In addition to <strong>the</strong>se living and recreational quarters, an adequate number of offices and<br />

a geological laboratory were required. Finally, Casoc would also have to drill water wells, install<br />

its own plumbing system and build a power plant.