104 TOTAL REWARDS FOR TECHNICAL WORKERS

104 TOTAL REWARDS FOR TECHNICAL WORKERS

104 TOTAL REWARDS FOR TECHNICAL WORKERS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ASAC 2005,<br />

Toronto, Canada<br />

John W. Medcof<br />

Steven Rumpel<br />

McMaster University<br />

<strong>TOTAL</strong> <strong>REWARDS</strong> <strong>FOR</strong> <strong>TECHNICAL</strong> <strong>WORKERS</strong><br />

Research on rewards for high technology workers is reviewed using the Total<br />

Rewards framework and a theoretical analysis of Total Rewards performed.<br />

Suggestions for more effective practice and further research follow.<br />

Introduction<br />

Firms in industries whose fundamental driver is the creation of value from science and<br />

technology continue to face enormous challenges in environments marked by unrelenting<br />

technical change and global competition (Boutellier, Gassmann and von Zedtwitz, 2000; Serapio<br />

and Hayashi, 2004). Firms with the edge in attracting, retaining, motivating, and rewarding top<br />

technical people have the edge in these technological races. But high technology workers present<br />

unique challenges when it comes to rewards (Balkin, Markman and Gomez-Mejia, 2000) and<br />

those challenges arise from the distinct nature of high technology firms and R&D workers. There<br />

is a need for innovative practice, empirical research and conceptual development on issues related<br />

to rewards for R&D workers. This paper will focus on such workers, their reward preferences,<br />

and the reward arrangements that work best for them, using the Total Rewards framework.<br />

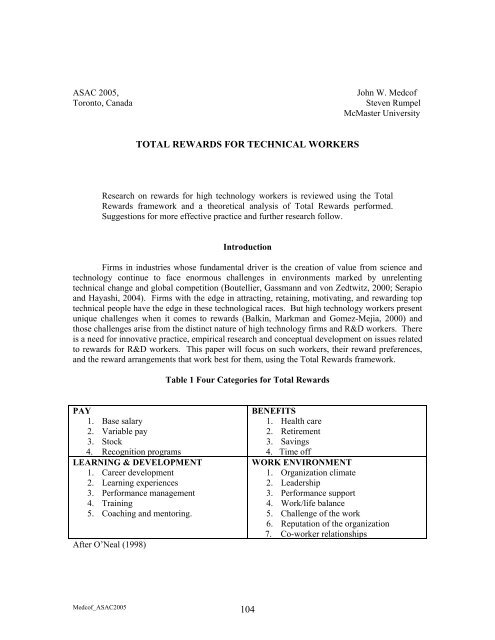

Table 1 Four Categories for Total Rewards<br />

PAY<br />

1. Base salary<br />

2. Variable pay<br />

3. Stock<br />

4. Recognition programs<br />

LEARNING & DEVELOPMENT<br />

1. Career development<br />

2. Learning experiences<br />

3. Performance management<br />

4. Training<br />

5. Coaching and mentoring.<br />

After O’Neal (1998)<br />

BENEFITS<br />

1. Health care<br />

2. Retirement<br />

3. Savings<br />

4. Time off<br />

WORK ENVIRONMENT<br />

1. Organization climate<br />

2. Leadership<br />

3. Performance support<br />

4. Work/life balance<br />

5. Challenge of the work<br />

6. Reputation of the organization<br />

7. Co-worker relationships<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

<strong>104</strong>

Total Rewards is a promising approach to employee rewards that has recently emerged<br />

from human resource management practice (Fischer, Gross and Friedman, 2003; Gross and<br />

Friedman, 2004; Kantor and Kao, 2004; Lyons and Ben-Ora, 2002; O’Malley and Dolmat-<br />

Connell, 2003; O’Neal, 1998; Petruniak and Saulnier, 2003; Pfau and Kay, 2002; Platt, 2000;<br />

Poster and Scanella, 2001; Thanasse, 2003; Watson, 2003; Zingheim and Schuster, 2001). It is an<br />

approach to rewards management which attempts a comprehensive inclusion of all the rewards<br />

people receive in the workplace. It embraces the “complete employee value proposition”;<br />

including financial rewards such as pay, stock options and benefits; and non-financial rewards<br />

such as training opportunities, interesting work, and support for work/life integration. Total<br />

Rewards has promise for the management of technical people as demonstrated by its application<br />

at IBM (Platt, 2000), Ethicon (Thanasse, 2003) and AstraZeneca (AstraZeneca, 2004). However,<br />

there has been no systematic consideration of Total Rewards in the R&D management literature.<br />

Currently, most thinking about rewards confines itself to “compensation”, which focuses<br />

almost entirely on pay and benefits as the principal rewards an organization can offer workers.<br />

Total Rewards goes beyond that and considers a wide array of other positive results of working<br />

(intrinsic and extrinsic) such as the social stimulation which people receive at work, the<br />

satisfaction they receive from doing their jobs well and the opportunity for learning and<br />

advancement at work. The assumption is that by thinking about rewards in this broader way we<br />

will understand them all, and their relationships to each other, in a more effective way, and this<br />

will lead to more effectively managed organizations. If the full spectrum of rewards and their<br />

real value to employees can be identified, optimal mixes of rewards for those employees can be<br />

designed and offered. For example, in some circumstances spending X dollars to increase<br />

employees’ pay may not be as effective an alternative as investing the X dollars in a much more<br />

effective career progression program that gives workers a strong sense that they are growing and<br />

developing in the organization and that they have a bright future there. Under the Total Rewards<br />

framework we thus can envision trading off pay against career growth opportunities. This tradeoff<br />

might not have been thought of if pay were considered a reward and career growth a part of<br />

training. Total Rewards thus promises to overcome some of the sticking points that are created<br />

by the current set of silos used in human resource management practice.<br />

O’Neal (1998) and Kantor and Kao (2004) divide Total Rewards into four categories as<br />

shown in Table 1. For efficiency of presentation we will use this widely accepted four category<br />

model in this paper. From this we can see the comprehensive nature of Total Rewards.<br />

Proponents of Total Rewards emphasize its value for attracting and retaining workers. If<br />

the full spectrum of rewards offered by an organization is presented to recruits in a structured<br />

way, the organization will be more attractive than will firms which emphasize only pay and<br />

benefits. If the current employees of a firm are kept apprised of the complete set of rewards they<br />

are currently receiving, they will be less likely to find other firms to be attractive alternatives. It<br />

is important to effectively communicate to employees all the rewards they receive from their<br />

work as this cultivates the sense that this set of rewards is not available elsewhere and that this<br />

firm is an “employer of choice”.<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

105

Proponents of Total Rewards have paid less attention to the ways in which Total Rewards<br />

could be used to influence organizational practices that directly impact work performance.<br />

However, the potential is there to do just that. For example, Total Rewards encompasses the<br />

intrinsic rewards employees receive from working. The framework thus has a conceptual link to<br />

job design, which can be used to ensure that employees do get intrinsic rewards from their tasks.<br />

Job design has long been considered to be an important mechanism for improving individual and<br />

organizational performance. Total Rewards offers the prospect of using job design even more<br />

effectively, by thinking of it as a reward delivery mechanism, in the same context as pay,<br />

benefits, social rewards, and others.<br />

There is no “one best way” to implement Total Rewards. Every firm is unique and,<br />

although organizations can learn from each other, each should develop its own solution. In short,<br />

Total Rewards is a strategy to meet the needs of both the organization and the employee in a way<br />

that helps employees understand the full value proposition they work under.<br />

Comparisons of Reward Categories<br />

Our literature review of rewards for R&D staff found only one study which compared<br />

rewards from all four Total Rewards categories. Three others compared more than one category<br />

but not all four. These papers will now be reviewed.<br />

Kochanski and Ledford (2001) studied the importance of various rewards in the turnover<br />

decisions of 210 high technology workers using five reward types: work content, affiliation,<br />

indirect financial, direct financial and career. Work content and affiliation were the most<br />

important, with 75% and 72% of respondents, respectively, saying they are “very important” or<br />

“extremely important” in the decision. Career development, indirect financial and direct financial<br />

rewards were judged “very” or “extremely important” by 62%, 65% and 64%, respectively. The<br />

rewards of Kochanski and Ledford can be aligned with O’Neal’s (1998) four types. Work<br />

content and affiliation from Kochanski and Ledford fit under O’Neal’s Work Environment.<br />

Indirect financial corresponds to Benefits. Direct financial with Pay. Career with Learning and<br />

Development. The ranking is shown in Table 2.<br />

Table 2 Ranking of Importance of Total Rewards in Various Studies<br />

Research Studies<br />

Rewards Rankings<br />

Work<br />

Environment<br />

Benefits Pay Learning and<br />

Development<br />

Kochanski & Ledford (2001) 1 2 2 2<br />

Kochanski, et al (2003) 1 - 3 2<br />

Chen et al (1999) 1 - 2 -<br />

Keller et al (1996) 1 - 2 -<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

106

Kochanski, Mastropolo and Ledford (2003) were also concerned with retention issues in<br />

their survey of 1999 R&D unit leaders. Respondents were asked which factors are most<br />

important for attracting and retaining R&D workers. The work itself was ranked most important,<br />

followed by long term career opportunities and a unique work culture. Cash compensation<br />

followed distantly. Aligning these with the Total Rewards framework: work itself fits with Work<br />

Environment; career opportunities with Learning and Development; unique work culture with<br />

Work Environment; and cash compensation with Pay. No facets of Benefits were included in the<br />

study. These results are also shown in Table 2.<br />

Chen, Ford and Ferris (1999) did a questionnaire study of 1109 technical workers in<br />

R&D units. Respondents were asked to rate the degree to which various reward types benefited<br />

the organization. The ranking of their rewards was: intrinsic, individual fixed, socioemotional,<br />

collective variable and individual variable. The correspondences with Total Rewards have<br />

intrinsic and socioemotional fitting under Work Environment; while individual fixed, collective<br />

variable and individual variable fit under Pay. Thus, their finding was that Work Environment<br />

rewards have greater benefits for the organization than does Pay, as seen in Table 2.<br />

Keller, Julian and Kedia (1996) studied the effect of a number rewards-related variables<br />

on the performance of 658 industrial and 1033 academic R&D teams. Independent variables<br />

included the degree of participation and cooperation in the team; the scientific and social<br />

importance of the work being performed by the team; and the satisfaction of team members with<br />

remuneration, opportunities for advancement, and supervision. The dependent variable was team<br />

performance. Work importance had the strongest effect upon productivity, followed by<br />

participation and cooperation. The three satisfaction variables had no consistent effect. Aligning<br />

these results with Total Rewards: Work Environment (importance of the work,<br />

participation/cooperation) clearly affects the productivity of R&D workers. There is minimal<br />

support for an effect of pay satisfaction on productivity, as shown in Table 2.<br />

Four papers comparing multiple rewards in the R&D context have now been reviewed<br />

and the results summarized in Table 2. They show that all four rewards categories are important<br />

to R&D workers and that Work Environment is the most important. A number of different<br />

rewards under Work Environment are individually important to R&D workers. There is little<br />

empirical work which bridges all four categories and more such research should be done. Now to<br />

papers focussing on only one reward category, starting with Learning and Development.<br />

Learning and Development<br />

Cordero, DiTomaso and Farris (1994) studied job satisfaction, turnover and career<br />

development opportunities in 3163 R&D professionals and found a positive relationship between<br />

managerial development opportunities and job satisfaction, but no relationship between technical<br />

development opportunities and job satisfaction. They also found that those with technical<br />

development opportunities were more likely to leave the employer but less likely to leave R&D<br />

for other areas of the firm. Those with managerial development opportunities were more likely to<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

107

leave R&D for other parts of the firm, but less likely to leave the employer. This shows career<br />

development opportunities have value for R&D workers but that assessing the benefits of<br />

providing such opportunities is not straightforward. For example, is turnover in the R&D unit a<br />

good measure of the effectiveness of reward practices? Providing managerial development<br />

opportunities does contribute to job satisfaction but also leads to higher turnover in R&D units.<br />

But at least some of that turnover results from technical people moving into management, which<br />

may be desirable. Career development programs for R&D employees need to be matched to their<br />

career development needs. Chen, Chang and Yeh (2003) argue that the career development<br />

programs provided to R&D employees need to be matched to their career development needs and<br />

at different career stages technical workers have different career development needs.<br />

In summary, Learning and Development rewards are important to R&D workers and<br />

should be included in Total Rewards programs for them. R&D workers have different career<br />

development needs depending upon their ages and their career aspirations. The use of turnover as<br />

a measure of the effectiveness of human resource practices has some subtleties which need to be<br />

addressed when it is used for that purpose.<br />

Work Environment<br />

Kim and Oh (2002) quantified the value of the Work Environment in their study of the<br />

economic and “intrinsic” compensation preferences of 1,214 scientists and engineers. Intrinsic<br />

compensation included feelings of achievement, personal growth and social status, which fall into<br />

the Work Environment category. Overall 37% of the sample said they received intrinsic rewards<br />

from their work. Respondents who said they got intrinsic rewards were asked to give the<br />

monetary value of those rewards as a percentage of their economic compensation. The average<br />

was 26.8%. This low value is not consistent with the importance of Work Environment found in<br />

the studies cited above. The difference may arise from Kim and Oh’s distinctive methodology for<br />

measuring the importance of intrinsic rewards. James (2002) advocates more attention to work<br />

environment variables based on some published data and his experience. His view is that the<br />

work itself is a very strong motivator for technical people. He states that research scientists and<br />

engineers have a deep-seated need for professional recognition and recommends a dual ladder<br />

recognition system. Mannheim, Baruch and Tal (1997) studied work centrality in a sample 727<br />

people employed by high technology firms in Israel. Although the sample included non-technical<br />

people as well as technical, their results are relevant here because the sampled firms were selected<br />

for their above average numbers of technical people. By Mannheim et al‘s definition, work<br />

centrality is the degree to which an individual is cognitively and attitudinally involved in the<br />

work role. They found work centrality significantly related to organizational commitment, career<br />

planning and wages, and weakly but positively related to work performance. This is yet more<br />

evidence of the importance of Work Environment. Harpaz and Meshoulam (2004) compared the<br />

“work centrality” of 461 technical, professional and managerial workers in high technology firms<br />

to that of 942 workers from traditional industries. Here again the “high technology” sample is not<br />

pure. The high tech group saw work as more central and had a more expressive work orientation<br />

than the other sample. The importance of interpersonal relationships did not differ significantly.<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

108

Overall, the empirical data on the Work Environment suggest that it is very important for<br />

R&D workers and deserves more research attention than it has received to date. This suggests<br />

that Total Rewards programs for R&D workers should give it more importance than it might have<br />

in programs for others. There are many facets of Work Environment included in these studies<br />

which suggests that Total Rewards programs for R&D workers might usefully divide it into<br />

multiple categories that have equal status with Pay, Benefits and Learning and Development. The<br />

work itself and the social milieu of work are good candidates to be additional principal categories.<br />

Pay<br />

Kim and Oh (2002) studied the compensation preferences of 1,214 scientists and<br />

engineers in basic, applied and commercial R&D, asking them to state what percentage of their<br />

compensation they would like to receive in each of three forms: fixed salary, individual<br />

performance-based, and team performance-based. All three groups had the strongest preference<br />

for fixed salary, with individual-based incentives a distant second, and team-based incentives a<br />

close third. Those in basic R&D had a stronger preference for fixed salary and less for teambased<br />

incentives than the other groups, which were not significantly different from each other.<br />

Risher (2000) studied current and emergent pay practices for R&D workers in the R&D<br />

organizations of 41 large companies well regarded for their R&D. He interviewed senior HR and<br />

compensation executives and found new approaches to compensation emerging. Although these<br />

new practices are still not widely adopted, Risher argues that they are well suited for R&D<br />

workers. The unique nature of R&D and the people who practice it justify the adoption of these<br />

practices, even if they are not used in the rest of the organization. The five “new” practices most<br />

commonly adopted are: (1) Broad banding of compensation categories, (2) Competency based<br />

pay emphasised over job based pay, (3) Market alignment of pay emphasized over internal equity,<br />

(4) Cash incentives such as profit sharing, (5) Recognition/reward practices (e.g. Award prize and<br />

ceremony). As Risher describes them, the compensation strategies of the firms he studied are<br />

consistent with Total Rewards. They see compensation as a tool for achieving firm goals and<br />

believe that compensation practices should be tailored to employees.<br />

This brings us to a series of studies that look at the relationship between Pay practices and<br />

organizational effectiveness in firms in which R&D workers are an important group of<br />

employees. These are studies of high technology companies defined as those which expend a<br />

high proportion of resources on R&D. Although technical people are not the only type of<br />

employees in such organizations they are a key group and effective management of them is<br />

critical to the success of the firm. In these studies the rewards preferences of R&D workers are<br />

not directly studied. Instead, the pay practices at the firm level are examined to see if they affect<br />

the performance of the firm. These studies provide a complementary perspective to those which<br />

look only at the preferences of employees. Two studies taking this approach are those of Diaz<br />

and Gomez-Mejia (1997) and of Tremblay and Chenevert (2004). Both papers argue that pay<br />

practices should be different in high technology firms because of their distinctive nature. Across<br />

the two papers, the practices that are predicted to be more prevalent and more effective in high<br />

technology firms are as follow. Pay levels will be more influenced by the characteristics of the<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

109

person rather than by the job. Pay includes elements of risk sharing (e.g. performance-based<br />

bonuses). Pay levels are set with more emphasis upon external equity than internal equity.<br />

Managers have significant discretion in setting their subordinates’ pay, as opposed to having a<br />

centralized pay-setting. Aggregate incentives are used whereby team and organization<br />

performance influences the individual’s pay. There is a long term orientation in pay policy. The<br />

firm takes a leader strategy by offering the best compensation levels in its sector. Individual<br />

incentives are offered. With somewhat different methodologies the two studies collected data<br />

from both high technology and low technology firms. They performed statistical analyses to see<br />

if there was any relationship between the prevalence of these pay practices and firm high/low<br />

technology status. They also analysed the degree to which these practices were more effective for<br />

high technology firms than for low. The results are summarized in Table 3.<br />

In Table 3 we see that four practices were included in both studies but only two of these<br />

were found in both to be more prevalent in high technology firms than in low; risk sharing and<br />

external equity. All the mechanisms that were included in only one study (person emphasis, long<br />

term orientation, leader strategy and individual incentives) were found to be more prevalent in<br />

high technology firms than low. Although the general thrust of these data is that high technology<br />

firms compensate differently from others, there is a need for more research in areas of ambiguity.<br />

The data on the relative effectiveness of the pay strategies was also mixed. Of the four practices<br />

included in both studies, only two (risk sharing and aggregate incentives) gave positive results in<br />

both. In addition, external equity was found by both studies not to be more effective for high<br />

technology firms. These data suggest that some compensation practices are more effective for<br />

high technology firms than for low, but further research is needed. There are several other studies<br />

whose findings are consistent with these two but which did not focus on high technology workers<br />

closely enough to be presented here (Balkin and Bannister, 1993; Balkan and Gomez-Mejia,<br />

1990; Balkin, Markman and Gomez-Mejia, 2000).<br />

Table 3 The Prevalence and Effectiveness of Pay Practices in High Technology Firms<br />

Pay Practices Prevalence Effectiveness<br />

D&G T&C D&G T&C<br />

1. Person, not job, emphasis yes - yes -<br />

2. Risk sharing yes yes yes yes<br />

3. External equity yes yes no no<br />

4. Discretion yes no yes no<br />

5. Aggregate incentives yes no yes no<br />

6. Long term orientation yes - yes no<br />

7. Leader strategy yes - no<br />

8. Individual incentives - yes - no<br />

This table compares the data of Diaz & Gomez-Mejia, 1997 (D&G) and Tremblay &<br />

Chenevert, 2004 (T&C). Both examined the degree to which compensation practices were more<br />

prevalent in high tech firms than in low (shown in columns labelled “Prevalence”). Both also<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

110

examined the degree to which the practices were more effective in high tech firms than in low<br />

(shown in columns labelled “Effectiveness”). In the columns, “yes” indicates that the study<br />

found the practice more prevalent or more effective in high technology firms, “no” indicates no<br />

significant difference, and “-“ indicates the practice was not included in the study.<br />

These studies suggest several conclusions. R&D workers do not value pay as highly as<br />

do other workers. R&D workers prefer most of their pay to be fixed, but believe that some<br />

should be in the form of individual and team incentives. In firms for which R&D is of high<br />

strategic importance, risk sharing and an emphasis upon personal capabilities are the two pay<br />

practices most consistently found to be related to firm performance. Discretion for managers,<br />

individual incentives and long term orientation also receive some support. These results support<br />

the proposition that R&D workers should be compensated differently to achieve worker<br />

satisfaction and firm performance.<br />

Benefits<br />

Only two papers have empirical data on the role of benefits. O’Neal (1998) reports that,<br />

for workers in general, benefits rank just after pay in the order of reward importance. Kochanski<br />

and Ledford (2001) found Benefits ranked behind Work Environment and tied with Pay and<br />

Learning and Development in ratings of reward importance. This suggests that Benefits should<br />

be receiving more empirical attention than has hitherto been the case.<br />

Conclusions from the Literature Review<br />

This review of the empirical research on reward importance and practices in R&D shows<br />

the literature to be rather thin, but it does suggest a number of conclusions and directions for<br />

future work. The following seem warranted.<br />

1. All four rewards categories are important to R&D workers and should be<br />

systematically included in rewards programs for them, and a Total rewards<br />

framework is a promising approach to doing so.<br />

This is shown in Table 2 which summarizes the studies which compared more than one<br />

reward category. It is also seen in the studies looking at only one reward at a time. R&D workers<br />

consistently rated all categories of rewards to be important. However, there is a paucity of<br />

research that includes all four categories in the same study. Such research is necessary if the<br />

rewards are to be systematically compared and the complete employee value proposition for<br />

R&D workers is to be understood. The relationships of these different rewards to organizational<br />

performance should be explored empirically, as has been done for pay.<br />

2. Work environment is more important to R&D workers than it is for most other<br />

workers and accordingly should be given more emphasis in rewards management<br />

programs for them.<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

111

In the comparative empirical studies summarized in Table 2 Work Environment is<br />

consistently rated as the most important reward category for R&D workers. Although it can be<br />

argued that this may not indicate that Work Environment is ultimately more important than<br />

competitive Pay and Benefits, it surely indicates the high importance of Work Environment.<br />

The Job Characteristics Model (Hackman and Oldham, 1980) focuses upon the work<br />

itself, one important component of the Work Environment. That model proposes that workers<br />

with high growth need strength respond better to enriched jobs than do workers with low growth<br />

need strength. Hackman and Oldham’s data show that “Professional or Technical” workers have<br />

a very high growth need strength compared to most of the other job categories they studied. This<br />

is consistent with the studies reviewed above showing that intrinsic rewards from the job itself are<br />

very important to R&D workers, more important than they are to most other categories of<br />

workers.<br />

3. Work Environment should not be treated as a single reward category for R&D<br />

workers but should be divided into several rewards which are treated separately in<br />

Total Rewards programs.<br />

For example, quality and importance of the work itself, quality of relationships with coworkers<br />

and recognition of work accomplishments have been found to be separately important to<br />

R&D workers. Given the overall importance of the Work environment category and the<br />

empirically demonstrated importance of these sub-categories, their individual importance should<br />

be acknowledged, included in Total Rewards plans, and articulated to R&D workers.<br />

4. Pay is an important category of rewards for R&D workers and should be<br />

prominently included in Total Rewards programs for them.<br />

Despite the results shown in Table 2, Pay practices have an important effect upon<br />

organizational performance, as shown in Table 3. However, overestimation of the importance of<br />

Pay is a temptation to be avoided. Research shows that Pay practices for R&D workers are, and<br />

should be, different from those for others. Risk sharing, person emphasis, aggregate incentives,<br />

discretion, individual incentives and long term orientation are practices that work in R&D.<br />

Evidence on others is mixed and more research is needed.<br />

5. Organizational circumstances can have a significant effect upon the effectiveness of<br />

Total Rewards programs.<br />

There is a number of situational variables that can affect Total Rewards and the growth<br />

and evolution of high technology firms provides a good example. When Microsoft was young the<br />

value of its stock rose at a phenomenal rate over a number of years. During that period the lure of<br />

company stock and the huge amount of money it could bring could easily overshadow the effect<br />

that any other rewards might have upon employees. Now that Microsoft is large and has a more<br />

stable stock value the monetary gains available through stock options are no longer as spectacular<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

112

and the role of other rewards has become more prominent. This completes the review of the<br />

empirical work on rewards for R&D workers. We now turn to a consideration of its theoretical<br />

basis.<br />

A Theoretical Basis for Total Rewards<br />

To date, a sound, broadly accepted, theoretical base for the Total Rewards has not been<br />

presented, but some beginnings have been suggested. For example, O’Malley and Dolmat-<br />

Connell (2003) argue that three facets of commitment (organizational, occupational and<br />

beneficial) can form the basis of a “total relationship strategy” with employees. They<br />

demonstrate how the concept of commitment can underlie various management strategies that<br />

have to do with rewards. In another example, Kantor and Kao (2004) suggest that Total<br />

Rewards’ attention to a spectrum of rewards is consistent with long traditions of psychological<br />

and organizational theorizing going back through Lawler, Drucker and Maslow. The rewards<br />

included in Total Rewards run the gamut from personal and career growth (Maslow’s selfactualization<br />

need), through recognition and promotion (esteem needs), to benefits (security<br />

needs) and salary (to satisfy physiological and other needs). These approaches have some<br />

promise as avenues for providing a stronger conceptual basis for Total Rewards.<br />

However, Expectancy Theory (Vroom, 1964), given its good empirical support (Van<br />

Eerde and Thierry, 1996), can probably provide a more solid theoretical base. Expectancy theory<br />

proposes that workers will be motivated to exert a high level of effort in their work if they<br />

perceive that their efforts will lead to good performance (expectancy), that that performance is<br />

instrumental in obtaining the rewards offered by the organization (instrumentality), and that those<br />

rewards have significant positive valence (value) to the worker. These constructs can encompass<br />

Total Rewards concepts.<br />

Total Rewards proposes that organizations should offer their employees a number of<br />

rewards (not just pay and benefits) and should ascertain the relative values of those rewards to<br />

their workers so they can offer the most cost effective mix. In expectancy theory the value of<br />

rewards is called valence. The ascertaining of the value of rewards would, then, involve<br />

measuring the valences of the rewards which the organization might offer to workers. This could<br />

be done using the measuring techniques developed for the study of Expectancy Theory.<br />

Expectancy Theory is flexible in this consideration for it does not pre-specify any particular<br />

number or type of rewards but does specify that the more rewards there are of positive valence<br />

(assuming expectancy and instrumentality), the more motivated will be the workers. Expectancy<br />

Theory proposes the inclusion of as many rewards, and as many types of rewards, as the<br />

organization may wish to include, as does Total Rewards.<br />

Expectancy Theory, however, leads us beyond this prescription from the proponents of<br />

Total Rewards. Those proponents suggest that the value of rewards be measured and that the<br />

most valued rewards be offered (subject to a cost effectiveness consideration). They do not<br />

consider some of the subtleties suggested by Expectancy Theory. Expectancy Theory states that<br />

for motivation to occur employees must perceive expectancy and instrumentality while Total<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

113

Rewards does not mention these considerations. The implication is that, for Total Rewards to<br />

work, the organization must make it clear to employees what rewards are offered and also how<br />

employees can access those rewards. The organization must also ensure that mechanisms are in<br />

place to ensure that employees who work hard and well actually get the rewards. Expectancy<br />

Theory shows that there is more to deploying Total Rewards than telling employees about the<br />

rewards available. For its part, Total Rewards introduces the idea of the cost effective rewards<br />

mix. Expectancy Theory provides no place in its framework for this consideration.<br />

This conceptual link between Expectancy Theory and Total Rewards suggests a<br />

broadening of the scope of both models. Expectancy theory has largely been applied to the<br />

question of how to motivate workers to work harder on their jobs. By linking it to total Rewards<br />

we open up the possibility of applying it to the question of how to motivate workers to choose<br />

one firm over another when seeking a job, and choosing to stay with a firm rather than moving to<br />

another. Since Expectancy theory is a theory about choice, it easily encompasses this particular<br />

set of choices. In choosing an organization, the worker, implicitly or explicitly, considers the<br />

valences of the rewards available from each, the expectancies and instrumentalities attached to<br />

each, and, therefore, the likelihood that those rewards will actually be attained. On the other<br />

hand, attaching Total Rewards to Expectancy Theory opens up the possibility of applying Total<br />

Rewards to questions of individual worker motivation to work hard. The conceptual route is now<br />

opened to consider how to add expectancies and instrumentalities to the Total Rewards package<br />

so that workers will do more than just join organizations, and stay with them, they will work hard<br />

at their jobs to continue to get their rewards.<br />

This discussion shows that although Total Rewards was conceived by practitioners who<br />

were primarily concerned with recruiting and retention issues, it can be given a sound theoretical<br />

basis in Expectancy Theory and shows promise for an extension into work motivation challenges.<br />

Implicit in these considerations is the need for further research on these possibilities.<br />

Conclusions<br />

The literature review in this paper suggests that a Total Rewards strategy should have<br />

business value in R&D. Most firms already offer rewards in all four categories, but most do not<br />

manage them optimally. This is of particular concern in R&D settings where data clearly indicate<br />

that career, personal development and the work itself are more important to R&D workers than to<br />

most others. R&D rewards strategy should give serious consideration to all four quadrants. A<br />

Total Rewards strategy has great potential to help improve the high turnover among technical<br />

workers that has been signalled by a number of authors (e.g. Cordero, DiTomasso and Farris,<br />

1994; Kochanski and Ledford, 2001; Kochanski et al, 2003). A number of suggestions for the<br />

implementation of Total Rewards, based upon the literature review, have been provided.<br />

The linking of Total Rewards to Expectancy Theory introduced several considerations.<br />

Attention to expectancy and instrumentality in the implementation of total rewards was suggested<br />

as well as the application of Total Rewards to issues of individual work motivation.<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

114

However, the literature review found no studies that rigorously evaluated the efficacy of<br />

any implemented Total Rewards program in R&D or elsewhere, although there is a report that<br />

IBM’s program is working well (Platt, 2000) and that Ethicon is pleased with its program<br />

(Thanasse, 2003). It is to be hoped that, if Total Rewards strategies are now being implemented,<br />

rigorous evaluations of their efficacy will soon appear in the literature.<br />

Total Rewards is an approach that makes pragmatic good sense. The empirical literature<br />

suggests that it is a viable strategy for R&D workers. The idea of articulating the complete<br />

employee value proposition holds much promise as a way to approach human resources issues.<br />

Total Rewards has the potential to guide research programs and to aid human resource managers<br />

in developing effective programs that support and fuel the strategic initiatives of organizations.<br />

References<br />

3M website, 2004. www.3M.com/profile/careers/comp.jhtml, accessed October 30, 2004.<br />

AstraZeneca website. www.astrazeneca-us.com/content/careers/benefits/totalrewards.asp,<br />

accessed October 30, 2004.<br />

Balkin, D.B. and Bannister, B.D. “Explaining pay forms for strategic employee groups in<br />

organizations”. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,. 66, (1993), 139-151.<br />

Balkin, D.B. and Gomez-Mejia, L.R. “Matching Compensation and Organizational Strategies.”<br />

Strategic Management Journal, 11(2), (1990) 153-169.<br />

Balkin, D.B., Markman, G.D. and Gomez-Mejia, L.R.. “Is CEO pay in high-technology firms<br />

related to innovation?” Academy of Management Journal, 43(6), (2000), 1118-1129.<br />

Boutellier, R., Gassmann, O., and von Zedtwitz, M., Managing Global Innovation: Uncovering<br />

the Secrets of Future Competitiveness. New York. (2000) Springer.<br />

Chen, C.C., Ford, C.M, and Farris, G.F. “Do rewards benefit the organization? The effects of<br />

reward types and the perceptions of diverse R&D professionals.” Transactions on Engineering<br />

Management, 46(1), (2000), 47-55.<br />

Chen, T.Y., Chang P.L. and Yeh, C.W. “Square of correspondence between career needs and<br />

career development programs for R&D personnel.” Journal of High Technology Management<br />

Research, 14, (2003) 189-211.<br />

Cordero, R., DiTomaso, N. and Farris, F. “Career development: Opportunities and likelihood of<br />

turnover among R&D Professionals.” Transactions on Engineering Management, 41(3), (1994).<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

115

Diaz, M.D.S. and Gomez-Mejia, L.R. :The effectiveness of organization-wide compensation<br />

strategies in technology intensive firms.” Journal of High Technology Management Research,<br />

8(2), (1997), 301-315.<br />

Fischer, K., Gross, S. E., and Friedman, H. M., “Marriott makes the business case for an<br />

innovative total rewards strategy.” Journal of Organizational Excellence, spring, (2003) 19-24.<br />

Gross, S. E., and Friedman, H. M., “Creating an effective total rewards strategy: holistic approach<br />

better supports business success.” Benefits Quarterly, 20(3), (2004), 7-12.<br />

Hackman, J. R., and Oldham, G. R., Work Redesign. Addison-Wesley, Don Mills, 1980.<br />

Harpaz, I. and Meshoulam, I. “Differences in the meaning of work in Israel: Workers in high-tech<br />

versus traditional work industries”. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 15,<br />

(2004) 163-182.<br />

James, W.M. “Best HR practices for today’s innovation management”. Research Technology<br />

Management, January-February, (2002), 57-60.<br />

Kantor, R. and Kao, T. “Total Rewards, Clarity from confusion and chaos.” World at Work<br />

Journal, 3 rd quarter, (2004), 7-15.<br />

Keller, R.T., Julian, S.D. and Kedia B.L. 1996. “A multinational study of work climate, job<br />

satisfaction, and the productivity of R&D teams.” Transactions on Engineering Management,<br />

42(1), (1996), 48-55.<br />

Kim, B. and Oh, H. “Economic compensation compositions preferred by R&D personnel of<br />

different R&D types and intrinsic values.” R&D Management, 32 (1), (2002), 47-59.<br />

Kochanski, J. and Ledford, G. “How to keep me” – retaining technical professionals.” Research<br />

Technology Management, May-June, (2001) 31-38.<br />

Kochanski, J., Mastropolo, P. and Ledford, G. “People solutions for R&D.” Research Technology<br />

Management, January-February, (2003) 59-61.<br />

Lyons, F. H., and Ben-Ora, D., “Total rewards strategy: The best foundation of pay for<br />

performance.” Compensation and Benefits Review, 34(2), (2003) 34-40.<br />

Mannheim, B., Baruch, Y. and Tal, J. “Alternative models for antecedents and outcomes of work<br />

centrality and job satisfaction of high-tech personnel.” Human Relations, 50(12), (1997) 1537.<br />

O’Malley, M. and Dolmat-Connell, J. “From total rewards to total relationship. A ‘committed’<br />

approach to compensation and benefits strategy.” World at Work Journal, second quarter, (2003).<br />

O’Neal, S. “The phenomenon of total rewards.” ACA Journal, Autumn, (1998), 6-18.<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

116

Petruniak, J. and Saulnier, P. “The total rewards sweet spot”. Workspan, 46(8), (2003), 38-41.<br />

Pfau, B. N., and Kay, I. T., “The five key elements of a total rewards and accountability<br />

orientation.” Benefits Quarterly, 18(3), (2002), 7-15.<br />

Platt, R.K. 2000. “The big picture at big blue: Total rewards at IBM.” Workspan, 43(8), (2000).<br />

Poster, C. Z., and Scannella, J. “Total rewards in an iDeal World.” Benefits Quarterly, 17(3),<br />

(2001), 23-28.<br />

Risher, H. “Compensating today’s technical professional.” Research Technology Management,<br />

January-February, (2000) 50-56.<br />

Serapio, M. G., and Hayashi, T., “Internationalization of Research and Development and the<br />

Emergence of Global R&D Networks.” Volume 8 in the series Research in International<br />

Business. (2004), Elsevier, Amsterdam.<br />

Thanasse, L. “Living by the Johnson & Johnson Credo: ETHICON thrives in a total rewards<br />

environment”. World at Work Journal, second quarter, (2003) 8-15.<br />

Tremblay, M. and Chenevert, D. “Effectiveness of compensation strategies in Canadian<br />

technology-intensive firms.” ASAC Quebec, (2004), 1-18.<br />

Van Eerde, W., and Thierry, H., “Vroom’s Expectancy Models and work-related criteria: A metaanalysis.”<br />

Journal of Applied Psychology, 10, (1996) 575-189.<br />

Vroom, V. H., Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley, 1964.<br />

Watson, S. 2003. “Building a better employment deal.” Workspan, 46(12) (2003), 48-51.<br />

Zingheim, P. Z., and Schuster, J. R., “Winning the talent game: Total rewards and the better<br />

workforce deal!” Compensation and Benefits Management, 17(3), (2001) 33-39.<br />

Medcof_ASAC2005<br />

117