BP - Health Care Compliance Association

BP - Health Care Compliance Association

BP - Health Care Compliance Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume Eleven<br />

Number Three<br />

March 2009<br />

Published Monthly<br />

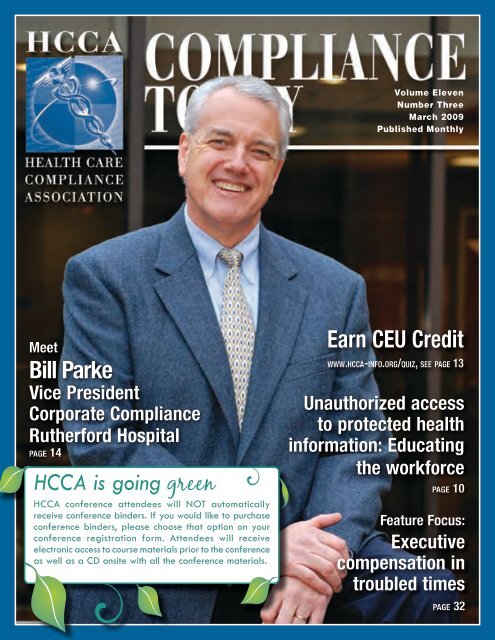

Meet<br />

Bill Parke<br />

Vice President<br />

Corporate <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

Rutherford Hospital<br />

page 14<br />

HCCA is going green<br />

HCCA conference attendees will NOT automatically<br />

receive conference binders. If you would like to purchase<br />

conference binders, please choose that option on your<br />

conference registration form. Attendees will receive<br />

electronic access to course materials prior to the conference<br />

as well as a CD onsite with all the conference materials.<br />

Earn CEU Credit<br />

w w w.h c ca-i n f o.org/quiz, see page 13<br />

Unauthorized access<br />

to protected health<br />

information: Educating<br />

the workforce<br />

page 10<br />

Feature Focus:<br />

Executive<br />

compensation in<br />

troubled times<br />

page 32

What’s Your Ethical Climate?<br />

Organizational climates change as<br />

organizations grow and evolve. So, how can<br />

you ensure attitudes and behaviors remain<br />

consistent with core values? Look to Global<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong>, the single provider offering a<br />

comprehensive framework to protect your<br />

organization from financial, legal, and<br />

reputational harm.<br />

• Ethics and compliance risk<br />

assessment<br />

• Code of conduct<br />

• Communication campaigns<br />

• Online, computer-based, and<br />

instructor-led training<br />

• Hotlines/Helplines<br />

• Case management<br />

• Investigations<br />

• Data analytics<br />

• Mystery shopping<br />

• Ethics and compliance evaluations<br />

• Employee exit interviews<br />

Contact the ethics and compliance leader<br />

that is already serving over one-half of<br />

America’s Fortune 100 and one-third of<br />

America’s Fortune 1000 along with colleges,<br />

universities, and government entities. And,<br />

we’re proud to claim greater than 450<br />

health care organizations as clients.<br />

With 27 years of experience and the most<br />

comprehensive product and service offering<br />

in the industry, Global <strong>Compliance</strong> can<br />

help you develop and maintain an ethical<br />

climate that’s appealing to employees,<br />

patients, and stakeholders.<br />

Making the world a better workplace TM<br />

13950 Ballantyne Corporate Place • Charlotte, NC, USA 28277<br />

866-434-7009 • contactus@globalcompliance.com<br />

www.globalcompliance.com<br />

© 2008 Global <strong>Compliance</strong>. All Rights Reserved.

Publisher:<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong>, 888-580-8373<br />

Executive Editor:<br />

Roy Snell, CEO, roy.snell@hcca-info.org<br />

Contributing Editor:<br />

Gabriel Imperato, JD, CHC, 888-580-8373<br />

Managing Editor/Articles and Advertisements:<br />

Margaret R. Dragon, 781-593-4924, margaret.dragon@hcca-info.org<br />

Communications Editor:<br />

Patricia Mees, CHC, CCEP, 888-580-8373, patricia.mees@hcca-info.org<br />

Layout:<br />

Gary DeVaan, 888-580-8373, gary.devaan@hcca-info.org<br />

HCCA Officers:<br />

Rory Jaffe, MD, MBA, CHC<br />

HCCA President<br />

Executive Director, California Hospital<br />

Patient Safety Organization (CHPSO)<br />

Julene Brown, RN, MSN, BSN, CHC, CPC<br />

HCCA 1st Vice President<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Officer<br />

Merit<strong>Care</strong> <strong>Health</strong> System<br />

Jennifer O’Brien, JD, CHC<br />

HCCA 2nd Vice President<br />

Shareholder<br />

Halleland Lewis Nilan & Johnson PA<br />

Urton Anderson, PhD, CCEP<br />

HCCA Treasurer<br />

Chair, Department of Accounting and<br />

Clark W. Thompson Jr. Professor in<br />

Accounting Education<br />

McCombs School of Business<br />

University of Texas<br />

Gabriel Imperato, Esq, CHC<br />

HCCA Secretary<br />

Managing Partner<br />

Broad and Cassel<br />

Shawn Y. DeGroot, CHC-F, CCEP<br />

Non-Officer Board Member of<br />

Executive Committee<br />

Vice President Of Corporate Responsibility<br />

Regional <strong>Health</strong><br />

Steven Ortquist, JD, CHC-F, CCEP, CHRC<br />

HCCA Immediate Past President<br />

Partner<br />

Meade & Roach<br />

CEO/Executive Director:<br />

Roy Snell, CHC, CCEP<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

Counsel:<br />

Keith Halleland, Esq.<br />

Halleland Lewis Nilan & Johnson PA<br />

Board of Directors:<br />

Marti Arvin, JD, CHC-F, CPC, CCEP, CHRC<br />

Privacy Officer<br />

University of Louisville<br />

Angelique P. Dorsey, JD, CHRC<br />

Research <strong>Compliance</strong> Director<br />

MedStar <strong>Health</strong><br />

Dave Heller<br />

Chief Ethics & <strong>Compliance</strong> Officer<br />

Qwest Communications<br />

Joseph Murphy, JD, CCEP<br />

Co-Founder Integrity Interactive<br />

Co-Editor ethikos<br />

Karen A. Murray, MBA, FACHE, CHC, CHA<br />

Corporate <strong>Compliance</strong> Officer<br />

Yale New Haven Hospital<br />

F. Lisa Murtha, JD, CHC<br />

Managing Director<br />

Huron Consulting Group<br />

Daniel Roach, Esq.<br />

Vice President <strong>Compliance</strong> and Audit<br />

Catholic <strong>Health</strong>care West<br />

Frank Sheeder, JD, CCEP<br />

Partner<br />

Jones Day<br />

Debbie Troklus, CHC-F, CCEP, CHRC<br />

Assistant Vice President<br />

for <strong>Health</strong> Affairs/<strong>Compliance</strong><br />

University of Louisville<br />

Sheryl Vacca, CHC-F, CCEP, CHRC<br />

Senior Vice President/Chief <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

and Audit Officer<br />

University of California<br />

Greg Warner, CHC<br />

Director for <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

Mayo Clinic<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Today (CT) (ISSN 1523-8466) is published by the <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong> (HCCA), 6500 Barrie Road, Suite 250, Minneapolis, MN 55435. Subscription<br />

rate is $295 a year for nonmembers. Periodicals postage-paid at Minneapolis, MN<br />

55435. Postmaster: Send address changes to <strong>Compliance</strong> Today, 6500 Barrie Road,<br />

Suite 250, Minneapolis, MN 55435. Copyright 2009 <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

All rights reserved. Printed in the USA. Except where specifically encouraged, no part of this<br />

publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means without prior written consent<br />

of the HCCA. For subscription information and advertising rates, call Margaret Dragon<br />

at 781-593-4924. Send press releases to M. Dragon, PO Box 197, Nahant, MA 01908.<br />

Opinions expressed are not those of this publication or the HCCA. Mention of products and<br />

services does not constitute endorsement. Neither the HCCA nor CT is engaged in rendering<br />

legal or other professional services. If such assistance is needed, readers should consult<br />

professional counsel or other professional advisors for specific legal or ethical questions.<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

INSIDE<br />

4 New developments in payment and public reporting<br />

of quality of care By Janice Anderson, Cheryl Wagonhurst,<br />

and Anil Shankar<br />

Penalties and incentives are steps toward pay for performance<br />

in Medicare reimbursements.<br />

10 CEU: Unauthorized access to protected health<br />

information: Educating the workforce By Mark C. Rogers<br />

Best practices to implement now to prevent fines, civil<br />

lawsuits, and adverse publicity later.<br />

14 Meet Bill Parke, Vice President, Corporate <strong>Compliance</strong>,<br />

Rutherford Hospital An interview by Greg Warner<br />

18 Letter from the CEO By Roy Snell<br />

Ethics works if everybody is ethical<br />

21 RAC demonstrations and inpatient rehabilitation—<br />

Vision of things to come? By Jane Snecinski<br />

Documenting “medical necessity” is key to avoiding RAC<br />

denial of payment for inpatient rehab facilities.<br />

25 Ask Leadership By John Falcetano<br />

Red Flag identity theft rules<br />

27 Newly Certified CHCs<br />

28 Physician office compliance—Are you monitoring your<br />

auditing and monitoring program? By Melissa Morales<br />

Opportunities to identify needed changes and corrective<br />

actions may be hiding just out of sight.<br />

32 CEU: Feature focus: Executive compensation in troubled<br />

times—Part 1 By Gerald M. Griffith<br />

Economic pressures, increased transparency, fiduciary duties,<br />

and stakeholder interests make compensation decisions more<br />

than a numbers game.<br />

38 <strong>Compliance</strong> 101: I just received a subpoena - Now<br />

what? By Andrea Ebreck and Karen Cincione<br />

State and federal privacy laws affect the appropriate response to<br />

requests for protected health information.<br />

40 Go Local<br />

42 Standing at the crossroads By Michael Spake<br />

Combining rules-based compliance with ethical and moral<br />

decisions to form an integrated operations model for excellence.<br />

46 Cyber Doctors By Sonya Burtner<br />

Electronic communications facilitate telemedicine, but also<br />

raise legal and compliance issues.<br />

51 Mandatory Stark reporting: Is a denouement nigh, or<br />

just another chapter in the saga?<br />

By Edwin Rauzi and Lisa Hayward<br />

CMS wants 400 hospitals to respond to its request for information.<br />

53 CEU: Charge Description Master compliance<br />

assessments By Joel W. Lipin<br />

Tips for assessing the accuracy of your CDM.<br />

55 Increased government oversight of managed care<br />

plans— Are you ready? By Steven E. Skwara<br />

Governmental requirements for detecting, investigating,<br />

and reporting fraud and abuse by “downstream” entities.<br />

61 New HCCA Members<br />

3<br />

March 2009

Affinity Group<br />

Meetings<br />

Hold your own<br />

meeting in conjunction<br />

with HCCA’s 2009<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Institute!<br />

Planning on attending the<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Institute? Need to<br />

hold a meeting of your own?<br />

Affinity group meetings are now<br />

available in conjunction with the<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Institute.<br />

Not only do you get the benefit<br />

of holding your meeting alongside<br />

the most comprehensive<br />

compliance conference for<br />

compliance professionals, but<br />

you also receive complimentary<br />

meeting room space at the<br />

conference site, your choice of<br />

a complimentary continental<br />

breakfast or an a m or pm<br />

break, and registration at the<br />

HCCA Member rate for your<br />

attendees.<br />

Affinity Group Meetings may be<br />

held on one of the following days:<br />

Saturday, April 25, 2009<br />

Wednesday, April 29,<br />

2009 (afternoon)<br />

Thursday, April 30, 2009<br />

To apply, please visit<br />

www.compliance-institute.org<br />

(conference tab) and fill out the<br />

Affinity Group Meeting form.<br />

Please return the completed<br />

form to the HCCA office.<br />

Questions? Contact<br />

Jodi Erickson Hernandez at<br />

952.405.7926 or email her at<br />

jodi.ericksonhernandez<br />

@hcca-info.org<br />

New developments in<br />

payment and public<br />

reporting of quality of<br />

care<br />

By Janice Anderson, Cheryl Wagonhurst, and Anil Shankar<br />

Editor’s note: Janice A. Anderson is a partner<br />

in Foley and Lardner, LLP in Chicago. She is a<br />

member of the <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Industry Team with<br />

25 years’ experience focusing on health regulatory<br />

and compliance issues and over 30 years’<br />

experience working in the health care industry.<br />

She may be contacted by e-mail at janderson@<br />

foley.com or by phone at 312/832-4500.<br />

Cheryl L. Wagonhurst is a partner with the Los<br />

Angeles office of Foley & Lardner LLP and a<br />

member of the firm’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Industry Team<br />

and White Collar Defense & Corporate <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

Practice. Ms. Wagonhurst is a former member<br />

of the board of directors of the <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong><br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> and currently serves on<br />

the advisory board of the Society of Corporate<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> and Ethics. She may be reached by<br />

telephone at 213/972-4681 and by e-mail at<br />

CWagonhurst@Foley.com.<br />

Anil Shankar is an associate with Foley &<br />

Lardner LLP in Los Angeles, California, and is a<br />

member of the firm’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Industry Team.<br />

He may be reached by phone at 213/972-4584<br />

or by e-mail at ashankar@foley.com.<br />

The long-term plan of Congress<br />

and the Center for Medicare and<br />

Medicaid Services (CMS) to tie<br />

health care reimbursement to the quality<br />

of health care services has been well-documented.<br />

CMS recently issued final rules that<br />

extend quality initiatives beyond inpatient<br />

hospitals to health care professionals and hospital<br />

outpatient departments. Authorized by<br />

the Medicare Improvements for Patients and<br />

Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA), CMS has<br />

now created incentive programs that affect<br />

the reimbursement of certain healthcare<br />

professionals and outpatient departments of<br />

hospitals.<br />

As a result of changes authorized by MIPPA<br />

and implemented through the 2009 Physician<br />

Fee Schedule Final Rule (PFS Final Rule),<br />

physicians and other eligible professionals<br />

may earn a 2% bonus for the reporting of<br />

quality data specified by the Secretary of the<br />

Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Human Services<br />

(Secretary-HHS), and a separate 2% bonus<br />

for successfully transitioning to an electronic<br />

prescription system. The 2009 Outpatient<br />

Prospective Payment System Final Rule<br />

(OPPS Final Rule) implements a similar<br />

quality data reporting incentive that applies<br />

to hospital outpatient departments. The<br />

OPPS Final Rule authorizes a 2% payment<br />

reduction for outpatient departments that fail<br />

to meet certain outpatient reporting requirements<br />

during FY 2009. Finally, three recently<br />

published National Coverage Determinations<br />

from CMS will make certain “never events”<br />

non-covered services.<br />

The onset of “pay for reporting” incentives<br />

can affect the pocketbook of professionals and<br />

entities which treat Medicare patients, but<br />

the incentives are also significant as a signal<br />

of CMS’ continued commitment to tying<br />

payment to the quality of services provided.<br />

The long-term move toward a “pay for quality”<br />

system (called a “value based purchasing<br />

plan” by CMS) has been implemented<br />

March 2009<br />

4<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org

incrementally, and CMS has made clear that<br />

the programs discussed below are intended<br />

as steps toward that goal. Many of the pay<br />

for reporting initiatives began as voluntary<br />

programs, designed to familiarize providers<br />

with the process of reporting and allow CMS<br />

to receive data on quality issues around the<br />

country. Under the new incentive programs,<br />

reporting remains voluntary, but there are<br />

now significant financial implications for<br />

reporting quality data. CMS makes clear that<br />

future programs may make reporting mandatory,<br />

and that payment may be tied to how<br />

well a provider performs on reported quality<br />

measures, rather than just on reporting.<br />

Physician Quality Reporting Initiative<br />

The Physician Quality Reporting Initiative<br />

(PQRI) began with the passage of the<br />

Tax Relief and <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Act of 2006<br />

(TRHCA), which directed the Secretary-<br />

HHS to implement a system for certain<br />

healthcare professionals to report data on<br />

selected quality measures. 1 Reporting began<br />

in July 2007. (Previously, physician’s could<br />

choose to participate in a Physician Voluntary<br />

Reporting Program.) Reports were not<br />

mandatory, but submission of the data in<br />

accordance with prescribed standards generated<br />

a bonus payment of 1.5% of the amount<br />

paid to the eligible professional for covered<br />

professional services during the reporting<br />

period. In July, 2008, MIPPA extended<br />

PQRI indefinitely and raised the bonus for<br />

years 2009 and 2010 to 2%. 2 The eligible<br />

professionals who can submit PQRI and<br />

receive the reporting bonus include certain<br />

midlevel practitioners, physicians, occupational<br />

therapists, qualified speech-language<br />

pathologists, and (starting in 2009) qualified<br />

audiologists. 3<br />

The importance of PQRI for physicians<br />

and other eligible professionals should not<br />

be underestimated. CMS has made clear<br />

that “pay for reporting” programs are a step<br />

toward a “pay for performance” or “pay<br />

for quality” reimbursement model (called<br />

a “value-based purchasing plan” by CMS).<br />

MIPPA directs the Secretary-HHS to submit<br />

to Congress a plan for the transition to<br />

pay for performance (P4P) with regard to<br />

physicians and other practitioners by May<br />

1, 2010. 4 On November 26, 2008, CMS<br />

presented an issues paper which outlines<br />

the initial framework for such a plan, and<br />

conducted a day-long listening session to<br />

discuss the anticipated transition. 5<br />

The incremental movement toward P4P<br />

mirrors the approach taken with regard to<br />

hospitals. The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005<br />

(DRA) established a 2% penalty for hospitals<br />

(referred to as subsection (d) hospitals) 6<br />

that fail to report quality data, and directed<br />

the Secretary-HHS to develop a plan for<br />

implementing P4P for these hospitals for<br />

2009. 7 That plan was submitted to Congress<br />

in November of 2007, but legislation has<br />

not yet been enacted in response. Subsection<br />

(d) hospitals are hospitals in the 50 States,<br />

Washington DC, and Puerto Rico, except for<br />

psychiatric hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals,<br />

hospitals whose inpatients are predominantly<br />

under 18 years old, and hospitals whose<br />

average inpatient length of stay exceeds 25<br />

days. A current bill drafted by Senator Baucus<br />

(D-Montana) and Senator Grassley (R-Iowa)<br />

would implement P4P for subsection (d)<br />

hospitals starting in 2012, and phase in<br />

over a five year period until 2016. 8 Similar<br />

legislation, or an expansion of the current bill,<br />

which extends P4P to physicians and other<br />

healthcare professionals should be anticipated.<br />

The ability to measure the quality of health<br />

care services accurately and efficiently is at<br />

the heart of CMS’ vision of a value-based<br />

purchasing plan. When PQRI was first<br />

implemented in 2007, the data tracked 74<br />

quality measures. The PFS Final Rule expands<br />

PQRI to include 153 quality measures for<br />

2009, up from 119 measures in 2008, but less<br />

than the 175 measures originally proposed by<br />

CMS. MIPPA requires the Secretary-HHS<br />

to ensure that the affected professionals have<br />

an opportunity to provide input during the<br />

development or selection of quality measures,<br />

and CMS has invited comments on the measures<br />

both for PQRI and for the anticipated<br />

transition to P4P.<br />

The 2009 quality measures include the<br />

2008 PQRI measures plus certain measures<br />

endorsed by the National Quality Forum<br />

(NQF) and/or the AQA (formerly the Ambulatory<br />

<strong>Care</strong> Quality Alliance). The 2009<br />

PQRI program also divides certain measures<br />

into seven measure groups, which are subsets<br />

of PQRI measures that have a particular clinical<br />

condition or focus in common. Details<br />

regarding the specific measures and measure<br />

groups included in PQRI for 2009 can be<br />

found at www.cms.hhs.gov/pqri. Technical<br />

specifications for reporting the measures and<br />

measure groups in the 2009 final listing can<br />

be found in the “Measures/Codes” tab of the<br />

PQRI section of CMS’ website.<br />

In addition to the quality measures which can<br />

be reported, the PFS Final Rule contains the<br />

criteria for submission which must be met to<br />

qualify for the incentive payment. In the past,<br />

reporting has encountered numerous hiccups.<br />

CMS data reveal that in 2007, just over half<br />

of those who participated successfully met<br />

the program and reporting requirements<br />

and received the reporting bonus. 9 In<br />

addition, many participants had difficulty<br />

accessing the confidential feedback reports<br />

CMS provided. These reports contained<br />

information as to whether the participant<br />

had met the criteria for satisfactory reporting,<br />

the amount of the incentive earned, and<br />

Continued on page 7<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

5<br />

March 2009

AUTOMATE YOUR COMPLIANCE AND RISK MANAGEMENT PROGRAM<br />

•<br />

Enforce Consistency<br />

Cost<br />

Streamline Processes<br />

•<br />

Mitigate Risk<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Reduce<br />

Policy Management<br />

Contract Management<br />

Remediation Projects<br />

Enterprise Risk Management<br />

Incident Management & Reporting<br />

Audit Management<br />

Regulation Management<br />

Surveys<br />

Liability<br />

Where <strong>Compliance</strong> Comes Full Circle<br />

•<br />

• Increase Productivity<br />

Decrease<br />

•<br />

Drive Accountability<br />

Enhance <strong>Compliance</strong> Visibility<br />

•<br />

Contact us today to view a free demo.<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> 360 assists <strong>Health</strong>care Organizations comply with:<br />

CMS<br />

OIG’s Annual Work Plan<br />

US Sentencing Commission Guidelines<br />

Stark Law<br />

Medicare Part D<br />

HIPAA<br />

Integrity Agreements<br />

March 2009<br />

6<br />

www.compliance360.com<br />

678.992.0262

New developments in payment and public reporting of quality of care ...continued from page 5<br />

their measure performance rates. CMS has<br />

worked to streamline the process and educate<br />

eligible professionals about how to meet the<br />

requirements and is seeking ways to make<br />

accessing the feedback reports easier, but<br />

these difficulties emphasize the importance<br />

of becoming familiar with the system prior to<br />

the anticipated transition to a P4P reimbursement<br />

scheme.<br />

Eligible professionals have several options<br />

available for reporting the data and qualifying<br />

for the 2% bonus. The options differ<br />

based on whether the professional chooses a<br />

claims-based or registry-based approach and<br />

whether the reporting pertains to individual<br />

measures or measure groups. The options<br />

available for claims-based submission of<br />

individual measures are the most restrictive.<br />

Registry-based reporting permits a physician<br />

to report through an authorized outside<br />

organization, such as certain trade associations.<br />

Registry-based submission using several<br />

different options is permitted and, for 2008<br />

PQRI, there are 32 registries qualified to<br />

submit quality measures on behalf of eligible<br />

professionals. The PFS Final Rule sets forth<br />

the process that registries must go through<br />

in order to be qualified to submit data for<br />

eligible professionals for the 2009 PQRI<br />

program. There are six options available to a<br />

professional reporting on measure groups.<br />

CMS does not, at this time, accept quality<br />

data through electronic health record (EHR)<br />

submission; however, it intends to test EHR<br />

vendors and their products during 2009 to<br />

determine if EHR reporting can be used<br />

in the future. If EHR vendors meet CMS’<br />

qualifications to participate in the PQRI testing<br />

process, their systems can submit quality<br />

measure data to CMS for PQRI on behalf of<br />

eligible professionals who use the systems.<br />

In addition, MIPPA directs CMS to publicly<br />

report the names of eligible professionals who<br />

satisfactorily report quality data for 2009. 10<br />

This marks a significant departure from the<br />

PQRI programs of 2007 and 2008, and is<br />

another of CMS’ strategies for improving the<br />

quality of health care services. The names of<br />

successful reporters will be posted in 2010 on<br />

a “Physician and Other <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Professional<br />

Compare” website. 11 Although the<br />

individual quality data will not be posted, the<br />

PFS Final Rule responded to comments about<br />

publishing the data and stated that CMS’<br />

goal was to “eventually make performance<br />

information available.” 12 The public posting<br />

of successful reporters should be regarded as<br />

the first step toward this process, and will lead<br />

to a website for physicians and other eligible<br />

professionals comparable to http://hospitalcompare.hhs.gov.<br />

E-Prescribing incentive program<br />

MIPPA and the PFS Final Rule also enact<br />

a separate incentive payment program for<br />

health care professionals who transmit a<br />

majority of their prescriptions electronically<br />

(e-prescribe). As with PQRI, the e-prescription<br />

incentive program is the next step in<br />

a long-term plan to improve the quality<br />

of care in the United States. Congress, in<br />

response to findings that e-prescription<br />

could prevent a significant number of<br />

medical errors, enacted a law in 2003 to help<br />

develop the infrastructure for its wider use. 13<br />

The law made drug plans’ acceptance of<br />

e-prescriptions a requirement for participation<br />

in the part D prescription drug benefit<br />

under Medicare, beginning in 2006, and<br />

CMS proclaimed the measure to be “one<br />

of the key action items in the government’s<br />

plan to expedite the adoption of electronic<br />

medical records and build a national<br />

electronic health information infrastructure<br />

in the United States.” 14 MIPPA takes the<br />

next step toward greater use of e-prescribing<br />

by creating significant financial incentives<br />

for physicians and other professionals who<br />

qualify as successful e-prescribers.<br />

Under MIPPA, a successful e-prescriber is an<br />

eligible professional who, for a given reporting<br />

period, reports all the quality measures<br />

specified by the Secretary-HHS that relate to<br />

e-prescribing in at least 50% of the instances<br />

in which the measure could be reported by<br />

the professional. However, the PFS Final<br />

Rule included only one quality measure to<br />

be reported in the e-prescribing program,<br />

which relates to the capacity for and use of<br />

e-prescribing measures. In 2008, this quality<br />

measure was included in the PQRI, but was<br />

removed by MIPPA and made part of the<br />

separate e-prescribing incentive program for<br />

2009. Although there is only one measure for<br />

the 2009 reporting period, CMS has said that<br />

it intends to consider the use of additional<br />

prescribing events as the basis of the incentive<br />

payment in future years. 15<br />

The reporting of e-prescription occurs through<br />

Medicare billing codes. To report one of the<br />

available codes for e-prescriptions, professionals<br />

must have a qualified e-prescribing<br />

system in place, and must have: (1) used it<br />

for all the prescriptions; (2) not generated any<br />

prescriptions during the encounter; or (3)<br />

been prevented from using the system by law,<br />

request of the patient, or the inability of the<br />

pharmacy system to receive e-prescriptions.<br />

CMS compares reported e-prescribing billing<br />

codes against the events reported to determine<br />

whether the professional qualifies as a successful<br />

e-prescriber. 16 Professionals have discretion<br />

in choosing the system they wish to use for<br />

e-prescribing; however, the system chosen<br />

must have the functionality established by the<br />

Medicare Part D e-prescribing standards. 17<br />

The financial incentives authorized by MIPPA<br />

take two forms. Starting in 2009, successful<br />

Continued on page 9<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

7<br />

March 2009

March 2009<br />

8<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org

New developments in payment and public reporting of quality of care ...continued from page 7<br />

e-prescribers will receive an incentive<br />

payment. The bonus begins at 2% for years<br />

2009 and 2010, but decreases in subsequent<br />

years and is eliminated entirely by 2014.<br />

The payment is separate from the incentive<br />

payments made under the PQRI, meaning<br />

eligible professionals could receive incentive<br />

payments of up to 4% in 2009. Second,<br />

beginning in 2012, a payment differential<br />

takes effect which penalizes prescribers<br />

by 1% if they do not qualify as successful<br />

e-prescribers. The amount of this differential<br />

increases in subsequent years to a maximum<br />

reduction of 2% by 2014. Thus, eligible professionals<br />

are offered incentives to transition<br />

to e-prescribing in the short-term, but these<br />

incentives steadily transition into penalties<br />

for failure to adopt and use an e-prescribing<br />

system in the future.<br />

The definition of “eligible professionals” for<br />

the e-prescribing initiative is the same as for<br />

the PQRI, and includes physicians as well as<br />

physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners<br />

(NPs), clinical psychologists, registered<br />

dietitians, physical therapists, and qualified<br />

audiologists. However, eligibility is restricted<br />

to only those professionals who have prescribing<br />

authority, which may vary from state to<br />

state for certain types of practitioners, based<br />

on the scope of their practice. Moreover,<br />

to qualify for the incentive, the reported<br />

code for e-prescribing must constitute at<br />

least 10% of the professional’s total Part B<br />

allowed charges. This limitation was enacted<br />

by Congress so that only those physicians<br />

or other eligible professionals who have the<br />

opportunity to prescribe a sufficient number<br />

of prescriptions can receive the incentive.<br />

CMS will publish the names of successful<br />

electronic prescribers for the 2009 E-Prescribing<br />

Incentive Program on the Physician and<br />

Other <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Professional Compare<br />

Website (http://www.medicare.gov/Physician/<br />

Home.asp?bhcp=1). This means that both<br />

successful PQRI reporters and successful<br />

electronic prescribers now will be publicly<br />

reported by 2010.<br />

Hospital outpatient quality data reporting<br />

program<br />

The OPPS Final Rule, released November 18,<br />

2008, implements another incentive program<br />

designed to encourage reporting quality<br />

data. 18 The rule expands upon existing<br />

hospital reporting requirements for outpatient<br />

services and implements the Hospital<br />

Outpatient Quality Data Reporting Program<br />

(HOP QDRP), which reduces hospital<br />

outpatient payment rates by up to 2% if the<br />

hospital fails to meet the outpatient reporting<br />

requirements.<br />

HOP QRDP was authorized by the Tax<br />

Relief and <strong>Health</strong>care Act (TRCHA) in 2006,<br />

to begin operating in 2009. 19 The 2008<br />

OPPS Final Rule established seven quality<br />

measures relating to outpatient services,<br />

which were to be reported beginning in<br />

April, 2008. 20 Five of these measures apply<br />

to emergency departments and relate to acute<br />

myocardial infarction treatment, and two<br />

relate to outpatient surgery and the prevention<br />

of surgical infection. This year’s OPPS<br />

Final Rule adds four new quality measures for<br />

FY 2009, focused on MRI of lumbar spine,<br />

mammography, abdominal CT, and thoracic<br />

CT. The adequate reporting of these measures<br />

will be used to determine if a hospital should<br />

be subject to the 2% reduction for FY 2010.<br />

The OPPS Final Rule also lists 18 different<br />

measures in nine measure sets from which<br />

additional quality measures could be selected<br />

for inclusion in HOP QDRP for FY 2011<br />

and beyond.<br />

The OPPS Final Rule explains the manner by<br />

which CMS will apply the 2% reduction in<br />

OPPS payment rates if a hospital fails to meet<br />

reporting requirements under HOP QDRP.<br />

The national unadjusted payment rates for<br />

many services paid under OPPS equal the<br />

product of the OPPS conversion factor and<br />

the scaled relative weight for the ambulatory<br />

payment classification (APC) to which the<br />

service is assigned. The OPPS conversion<br />

factor is updated annually, and CMS proposes<br />

to apply the 2% reduction to the conversion<br />

factor for purposes of implementing the<br />

HOP QDRP payment adjustment. This<br />

means that the payment reduction for failing<br />

to report under HOP QDRP will only apply<br />

to those OPPS services which are adjusted<br />

annually based on the conversion factor. For<br />

CY 2009, the reduction would be determined<br />

by multiplying the full national unadjusted<br />

payment rate for the applicable CPT code by<br />

0.981.<br />

Like the “Reporting Hospital Quality Data<br />

Annual Payment Update” program, CMS<br />

intends that reporting under HOP QDRP<br />

will be made public and has stated that the<br />

data will be posted to the CMS website by<br />

2010. Hospitals will have an opportunity to<br />

review the data prior to publication. CMS is<br />

exploring whether Hospital Compare or other<br />

sites might be used for reporting of hospital<br />

outpatient quality data.<br />

<strong>Health</strong> care-associated conditions and<br />

“never” events<br />

Part of the value-based purchasing program<br />

already implemented by CMS has been a<br />

denial of payment for certain conditions considered<br />

to be preventable. In October 2008,<br />

CMS implemented its Hospital-Acquired<br />

Condition payment penalty to further that<br />

initiative. 21 Applicable to inpatient services<br />

only, the penalty denies any additional DRG<br />

payment for certain preventable complications<br />

that were not present on admission.<br />

Examples of hospital-acquired conditions<br />

Continued on page 52<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

9<br />

March 2009

Unauthorized access<br />

to protected health<br />

information: Educating<br />

the workforce<br />

By Mark C. Rogers, Esq.<br />

Editor’s note: Mark C. Rogers is a member of the more likely to encounter this problem in the<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> and Corporate Practice Groups at context of a workforce member inappropriately<br />

accessing the medical record of either<br />

The Rogers Law Firm (www.therogerslawfirm.<br />

com) in Boston, Massachusetts. He is also a a co-worker or a family member or friend.<br />

member of the firm’s Consulting Division (www. Beyond the consequences to the workforce<br />

trcgsolutions.com). Mark is Co-Editor of The member who commits the violation, the<br />

Boston <strong>Health</strong> Law Reporter and is an adjunct health care entity also faces exposure to fines,<br />

faculty member at New England School of Law, civil lawsuits, and adverse publicity. This<br />

where he teaches <strong>Health</strong> Law. Mr. Rogers may be article looks at the issue of unauthorized<br />

reached by e-mail at mrogers@therogerslawfirm. access to PHI by workforce members and<br />

com or by telephone at 617/723-1100, ext. 229. what health care entities can do to address<br />

this growing problem.<br />

<strong>Health</strong> care entities have come a long<br />

way in terms of health information<br />

privacy since the enactment Over the last two years, there has been an<br />

Increasing number of incidents<br />

of the HIPAA [<strong>Health</strong> Insurance Portability increase in the number of workers within<br />

and Accountability Act] Privacy and Security health care entities who inappropriately<br />

Rules. The overwhelming majority of health access, and in some cases disclose, the PHI<br />

care entities have worked to create a culture of celebrities. Britney Spears, Maria Shriver,<br />

of commitment to protecting the health and George Clooney are just a few of the<br />

information of their patients. Nevertheless, celebrities who have reportedly had their<br />

despite this commitment to privacy, health PHI inappropriately accessed in a health care<br />

care entities continue to face violations of the entity setting. 1 Recently, Richard Collier, an<br />

HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules by members<br />

of their workforce--including physicians, League’s Jacksonville Jaguars, had his PHI<br />

offensive tackle with the National Football<br />

nurses, technicians, aides, administrative inappropriately accessed while he was recovering<br />

from surgery at a Jacksonville, Florida<br />

assistants, managers, and executives. One of<br />

the more common of these violations, and hospital. According to reports of the media,<br />

certainly one of the most well-publicized, is twenty hospital employees accessed Collier’s<br />

online medical file using the hospital’s<br />

unauthorized access to protected health information<br />

(PHI). In layman’s terms: looking at computer system. 2<br />

other people’s medical records when there is<br />

no legitimate reason to be doing so.<br />

Perhaps the most well-best known incident<br />

of a celebrity’s PHI being inappropriately<br />

Although there are well-publicized incidents accessed is that of Hollywood actress, Farrah<br />

of this occurring with the medical records Fawcett. In February of 2008, Lawanda<br />

of celebrities, a health care entity is much Jackson, a former administrative specialist for<br />

the UCLA <strong>Health</strong> System, was indicted by a<br />

federal grand jury for illegally accessing the<br />

PHI of Fawcett and selling it to the National<br />

Enquirer for $4,600. Jackson faces up to<br />

ten years in prison if she is convicted. It is<br />

also possible the National Enquirer could be<br />

charged as a result of the ongoing investigation<br />

by the U.S. Attorney’s Office. 3 The<br />

indictment of Lawanda Jackson was the result<br />

of an investigation by the State of California<br />

into unauthorized access to PHI within<br />

the UCLA <strong>Health</strong> System. The investigation<br />

showed that in addition to celebrities,<br />

workforce members had inappropriately<br />

accessed the PHI of over 1,000 other patients<br />

since 2003. 4<br />

The problem with unauthorized access to<br />

PHI is, of course, not unique to the UCLA<br />

<strong>Health</strong> System. <strong>Health</strong> care entities across<br />

the country face this problem on an ongoing<br />

basis. For the most part, unauthorized access<br />

to PHI within a health care entity is most<br />

likely to occur in the context of a workforce<br />

member inappropriately accessing the PHI<br />

of a fellow co-worker, friend, neighbor, or<br />

relative who was a patient at the facility.<br />

Potential consequences<br />

The unauthorized access of PHI by a workforce<br />

member of a health care entity presents<br />

a liability exposure to both the workforce<br />

member and the entity. The workforce member<br />

faces:<br />

n Disciplinary action by the covered entity,<br />

from a verbal warning to termination of<br />

employment. If the individual is a member<br />

of the health care entity’s medical staff, he/<br />

she also faces disciplinary action under the<br />

entity’s Medical Staff Bylaws.<br />

n A potential civil lawsuit from the individual<br />

whose PHI is the subject of the<br />

unauthorized access. Depending upon the<br />

circumstances of the underlying incident,<br />

this can include such claims as invasion<br />

March 2009<br />

10<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org

of privacy and infliction of emotional<br />

distress.<br />

n Criminal fines and/or penalties under<br />

both state and federal laws. An individual<br />

who knowingly obtains or discloses PHI in<br />

violation of HIPAA faces a fine of $50,000<br />

and up to one year in prison. The criminal<br />

penalties increase to $100,000 and up<br />

to five years in prison if the wrongful<br />

conduct includes false pretenses, and up<br />

to $250,000 and ten years in prison if the<br />

wrongful conduct includes the intent to<br />

sell, transport, or use individually identifiable<br />

health information for commercial<br />

advantage, personal gain, or malicious<br />

harm. 5 In addition, the workforce member<br />

likely will face state criminal charges as<br />

there have been a number of states that<br />

have recently strengthened their criminal<br />

laws pertaining to the privacy of personal<br />

information.<br />

The health care entity also faces a significant<br />

potential liability exposure as a result of a<br />

workforce member’s unauthorized access to<br />

PHI. First, the entity faces an investigation<br />

by both the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) of<br />

the United States Department of <strong>Health</strong> and<br />

Human Services (HHS) which is the agency<br />

that enforces the HIPAA Privacy Rule, and<br />

the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services<br />

(CMS) which is the agency that enforces<br />

the HIPAA Security Rule. Such investigations<br />

could lead to a potential fine of $100 per<br />

failure to comply with each HIPAA Privacy or<br />

Security Rule requirement. 6 Second, as with<br />

a workforce member, the entity also faces a<br />

lawsuit from the individual whose PHI is the<br />

subject of the unauthorized access. The lawsuit<br />

would likely include claims of negligence,<br />

negligent supervision and negligent infliction<br />

of emotional distress. Third, the entity faces<br />

civil fines and penalties under state law.<br />

Finally, workforce members’ unauthorized<br />

access to PHI can result in adverse publicity<br />

for the entity which has the potential to affect<br />

patient volume and in turn, revenues.<br />

All of this leads to the question as to how it is<br />

that incidents of unauthorized access to PHI<br />

are discovered. Certainly, audits performed by<br />

the entity which are mandated by the HIPAA<br />

Security Rule are a source of these discoveries.<br />

7 However, it is more likely that the audits<br />

are simply confirming what is already a<br />

rumor within the halls of the entity. Just as<br />

some may argue that it is human nature for<br />

a workforce member to “snoop” into another<br />

individual’s medical record, it is also human<br />

nature for that workforce member to discuss<br />

the contents of the medical record with others<br />

within the entity. This “water-cooler effect”<br />

necessitates that an entity undertake an<br />

investigation to determine whether there was<br />

indeed an incident of unauthorized access to<br />

PHI. A covered entity must mitigate, to the<br />

extent practicable, any harmful effect it learns<br />

was caused by the use or disclosure of PHI<br />

by its workforce in violation of the HIPAA<br />

Privacy Rule. 8 If an entity has confirmed<br />

through an investigation that an incident<br />

of unauthorized access to PHI occurred, an<br />

often overlooked provision of the HIPAA<br />

Privacy Rule requires the entity to list the<br />

incident and the name of the workforce<br />

member who committed the violation<br />

on the patient’s accounting of disclosures<br />

maintained by the entity. 9 Thus, by reviewing<br />

the accounting of disclosures, the patient will<br />

know who accessed their PHI and under what<br />

circumstances.<br />

Addressing the problem<br />

Even with the continued advancement of<br />

health information technology, it is unlikely<br />

that health care entities will ever be able to<br />

eradicate the problem of unauthorized access<br />

to PHI by members of their workforce. The<br />

temptation by certain individuals to view the<br />

PHI of others will, on occasion, overcome<br />

the compliance efforts by health care entities.<br />

Nevertheless, the response by health care<br />

entities to this inevitable truth cannot be<br />

to ignore the problem. To do so creates a<br />

significant potential liability exposure in<br />

an environment of increasing compliance<br />

enforcement. The Office of Inspector General<br />

of HHS recently criticized CMS for its failure<br />

to oversee and enforce the HIPAA Security<br />

Rule. 10 Such a public rebuke is likely to spur<br />

an increase in HIPAA enforcement by both<br />

CMS and OCR. Therefore, now is the time<br />

for health care entities to address the issue of<br />

unauthorized access to PHI by members of<br />

their workforce.<br />

Preventive measures<br />

The first step for a health care entity to effectively<br />

address the problem of unauthorized<br />

access to PHI is to undertake an assessment of<br />

its current HIPAA Privacy and Security policies<br />

and procedures. At the time the HIPAA<br />

Privacy and Security Rules became effective,<br />

many health care entities rushed to promulgate<br />

the required policies and procedures to<br />

meet the government-imposed deadlines. In<br />

doing so, they created the potential for generating<br />

inaccurate or inappropriate policies and<br />

procedures. Furthermore, the assessment and<br />

evaluation of a health care entity’s HIPAA<br />

Privacy and Security policies and procedures<br />

presents an opportunity to incorporate the<br />

best practices that have developed over the<br />

last several years with respect to HIPAA<br />

compliance. This includes best practices for<br />

detecting and preventing unauthorized access<br />

to PHI by a health care entity’s workforce<br />

members.<br />

This, in turn, leads to the second step a<br />

health care entity should undertake to effectively<br />

address the problem of unauthorized<br />

access to PHI by members of its workforce<br />

-- adoption of best practices. Obviously, a<br />

Continued on page 13<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

11<br />

March 2009

Enhance Quality of <strong>Care</strong> and Reimbursement Processing with:<br />

A Compelling Case for Clinical<br />

This one kit offers a handbook, strategy guide and<br />

training system to improve your organization’s<br />

clinical documentation quality.<br />

A Compelling Case for Clinical Documentation introduces the CAMP Method for<br />

Clinical Documentation Training – scientifically proven to substantially improve clinical<br />

documentation quality. Nominated for the Best Theory to Practice Award by the Academy<br />

of Management, this kit offers the most comprehensive guide on clinical documentation<br />

training every published. The kit includes:<br />

3 a two-volume strategy guide:<br />

1. Use Clinical Documentation to Achieve Strategic<br />

Alignment With Your Medical Staff<br />

2. Use the CAMP Method to Improve Clinical<br />

Documentation Quality<br />

3 the CAMP Method Overview training DVD<br />

3 the training system resource CD<br />

Documentation<br />

What is CAMP Method Training?<br />

Developed by Ruthann Russo, PhD, JD, MPH, RHIT, a lawyer with more than<br />

20 years of experience consulting for health care organizations, the CAMP Method is<br />

based on the established theories and practices of self-efficacy education. It relies on four<br />

components to increase participant self-efficacy: Coaching, Asking, Mastering, and Peer learning.<br />

The CAMP training system gives physicians the tools needed to consistently produce high quality clinical<br />

documentation and the conviction needed to do so.<br />

A Compelling Case for Clinical Documentation offers a complete, scientifically tested training system you<br />

can put to work, starting today. You are provided with a DVD that overviews the CAMP training system, as well as a resource<br />

CD with the precise training sequence and all the needed testing forms. For more information, visit www.hcca-info.org/books/.<br />

Qty<br />

Cost<br />

________ HCCA Member Price ...$355 $ _________<br />

________ Non-member Price........$395 $ _________<br />

________ Join HCCA!...................$200 $ _________<br />

Non-members, add $200 to join HCCA, and pay<br />

member prices for your order (regular dues $295/year)<br />

Bulk discounts available for HCCA members only. See<br />

chart at left to figure cost. All purchases receive free FedEx<br />

Ground shipping within continental U.S.<br />

Please make your check payable to HCCA.<br />

For more information, call 888-580-8373.<br />

Mail check to: 6500 Barrie Road, Suite 250<br />

Minneapolis, MN 55435<br />

Fax order to: 952-988-0146<br />

Total: $<br />

Please type or print:<br />

HCCA Member ID<br />

First Name M.I. Last Name<br />

Title<br />

Organization<br />

Street Address<br />

City State Zip<br />

Telephone<br />

Fax<br />

E-mail<br />

My organization is tax exempt<br />

Check enclosed<br />

Invoice me PO #<br />

Charge my credit card:<br />

Mastercard VISA American Express<br />

Account number<br />

Expiration date<br />

Cardholder’s name<br />

Cardholder’s signature<br />

Federal Tax ID: 23-2882664<br />

Prices subject to change without notice. HCCA is required to<br />

charge sales tax on purchases from Minnesota and Pennsylvania.<br />

Please calculate this in the cost of your order. The required sales<br />

tax in Pennsylvania is 7% and Minnesota is 6.5%.

Unauthorized access to protected health information: ...continued from page 11<br />

health care entity needs to approach the issue<br />

with a mindset that not all of the practices<br />

are best suited for their entity. A health<br />

care entity needs to go through the exercise<br />

of what best practices work for them. The<br />

following are just a handful of those best<br />

practices which health care entities have<br />

adopted in an attempt to detect and prevent<br />

unauthorized access to PHI by members of<br />

their workforce:<br />

n Auditing, auditing, auditing: <strong>Health</strong> care<br />

entities should enhance their auditing of<br />

electronic health records to ensure that<br />

members of their workforce are accessing<br />

only those records to which access is appropriate.<br />

Also, health care entities should<br />

communicate this enhancement and auditing<br />

to their workforce members.<br />

n VIPs/Workforce members: <strong>Health</strong> care<br />

entities should engage in targeted auditing of<br />

the electronic health records of workforce<br />

members and VIPs (celebrities, politicians,<br />

sports figures, trustees, donors, etc.) to<br />

assess for unauthorized access.<br />

n Reminders: <strong>Health</strong> care entities should<br />

consistently remind its workforce members<br />

that they are prohibited under federal law<br />

(and in some instances state law) from unauthorized<br />

access to PHI. These reminders<br />

should come in varying forms, including<br />

e-mails and mailings to their departments,<br />

offices, and homes. Also, it is worthwhile<br />

to have the compliance and/or privacy officer<br />

make these reminders in person (such<br />

as at departmental meetings).<br />

n Honeypots: <strong>Health</strong> care entities should<br />

consider using “honeypots” —which is the<br />

practice of creating a fictitious electronic<br />

health record (oftentimes using the name<br />

of a celebrity or VIP) and then monitoring<br />

that electronic health record to see if it is<br />

inappropriately accessed by a workforce<br />

member. Honeypots can be used as a<br />

general compliance tool or in instances<br />

where there is a suspicion that a specific<br />

workforce member or department is inappropriately<br />

accessing electronic health<br />

records.<br />

n Disciplinary actions: Perhaps the best<br />

method for a health care entity to demonstrate<br />

to its workforce how serious it takes<br />

the use of unauthorized access to PHI is to<br />

take strong disciplinary action in response<br />

to an incident. It is now common to<br />

suspend or terminate a workforce member<br />

who engages in this activity. A health<br />

care entity can get the attention of its<br />

workforce by publicizing these disciplinary<br />

actions (without identifying the specific<br />

workforce member involved).<br />

The final and perhaps most important step<br />

for a health care entity to take to effectively<br />

address the issue of unauthorized access to<br />

PHI is education. <strong>Health</strong> care entities need<br />

to educate their workforce about this topic<br />

and the consequences they face as individuals<br />

as a result of engaging in this type of activity.<br />

This education should take place at the time<br />

the individual enters the entity’s workforce<br />

(as part of a more comprehensive HIPAA<br />

training program) and should be mandatory.<br />

Continuing education programs should also<br />

reinforce the importance of this issue and<br />

should be mandatory. Again, it is critical that<br />

workforce members be educated about the<br />

potential consequences they face as a result of<br />

unauthorized access to PHI.<br />

Conclusion<br />

<strong>Health</strong> care entities face a significant liability<br />

exposure as a result of unauthorized access<br />

to PHI by members of their workforce. The<br />

most effective way for a health care entity to<br />

address this serious problem is to undertake<br />

(and follow through with) a comprehensive<br />

assessment and education plan. Although it<br />

is unlikely that a health care entity will be<br />

able to completely eliminate incidents of<br />

unauthorized access to PHI through such a<br />

course of action, it will nevertheless serve to<br />

minimize the entity’s liability exposure and<br />

demonstrate its commitment to protecting<br />

the health information of its patients. n<br />

1 Orenstein, Charles, Ex-worker indicted in celebrity patient leaks, Los Angeles<br />

Times (April 30, 2008); Orenstein, Charles, UCLA worker snooped<br />

in Spears’ medical records, Los Angeles Times (March 15, 2008).<br />

2 20 hospital workers fired for viewing Collier’s medical records, News-<br />

4JAX.com (November 17, 2008).<br />

3 Orenstein, Charles, Ex-worker indicted in celebrity patient leaks, Los<br />

Angeles Times (April 30, 2008); United States of American v. Lawanda<br />

Jackson, February 2008 Grand Jury Indictment.<br />

4 AP News, Not-guilty plea in celebrity medical snooping case, (November<br />

3, 2008).<br />

5 42 U.S.C. § 1320d-6.<br />

6 42 U.S.C. § 1320d-5.<br />

7 45 C.F.R. § 164.312(b).<br />

8 45 C.F.R. § 164.530(f).<br />

9 45 C.F.R. 164.528.<br />

10 Memorandum from Daniel R. Levinson, Inspector General of the<br />

United States Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Human Services to Kerry<br />

Weems, Acting Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid<br />

Services, regarding “Nationwide review of the Centers for Medicare and<br />

Medicaid Services <strong>Health</strong> Insurance Portability and Accountability Act<br />

of 1996 oversight” (A-04-07-05064) (October 27, 2008).<br />

Be Sure to Get Your<br />

CHC CEUs<br />

The CEU quiz will no longer be mailed<br />

with each issue of <strong>Compliance</strong> Today.<br />

To take the quiz and obtain credit,<br />

please go to www.hcca-info.org/quiz<br />

and select a quiz. Fill in your contact<br />

information and answer the questions.<br />

Print the completed form and FAX or<br />

MAIL it to Liz Hergert at HCCA.<br />

Articles related to the quiz in this issue of<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Today:<br />

n Unauthorized access to protected<br />

health information: Educating the<br />

workforce — By Mark C. Rogers,<br />

page 10<br />

n Feature focus: Executive<br />

compensation in troubled times—<br />

Part 1 — By Gerald M. Griffith,<br />

page 32<br />

n Charge Description Master<br />

compliance assessments —<br />

By Joel W. Lipin, page 53<br />

Questions? Please call Liz Hergert at<br />

888/580-8373.<br />

Please note that credit will be given only<br />

for quizzes received before the expiration<br />

date indicated on the quiz.<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

13<br />

March 2009

feature article<br />

Meet Bill Parke<br />

Vice President, Corporate <strong>Compliance</strong>, Rutherford Hospital<br />

March 2009<br />

14<br />

Editor’s note: This interview with Bill Parke<br />

was conducted by Greg Warner, Director for<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong>, Mayo Clinic and a member of the<br />

HCCA Board of Directors. Greg may be reached<br />

by telephone at 507/284-9029. Bill Parke may<br />

be reached in North Carolina by telephone at<br />

828/286-5360.<br />

GW: I always find it interesting to learn<br />

how others found their way into <strong>Compliance</strong>.<br />

Would you share a little of your background<br />

and how you ended up in <strong>Compliance</strong>?<br />

<strong>BP</strong>: I came to the health care field later,<br />

rather than sooner. I graduated with a degree<br />

in Economics from SUNY Cortland and<br />

spent several years trying my hand at a variety<br />

of “opportunities” in other industries. At<br />

the encouragement of a former professor, I<br />

interviewed for a position in administration<br />

at a small nursing home in rural Ohio. It was<br />

there that I started what has proven to be a<br />

very fulfilling career in health care administration.<br />

After doing some coursework at Ohio<br />

State University, I obtained my nursing home<br />

administrator license and worked for several<br />

years in the long-term care industry. Moving<br />

to western North Carolina, I eventually<br />

became the administrator of a hospital-based<br />

nursing home run by Rutherford Hospital,<br />

Inc. (RHI), a position I held for several years.<br />

As often happens in smaller hospital<br />

systems, you end up wearing more than one<br />

hat and that was my experience; I ended up<br />

being one of the corporate vice presidents<br />

with additional operational responsibilities. In<br />

1998, our then-CEO called me into his office<br />

for a chat. He said that there was a new push<br />

in the industry to establish something called<br />

a compliance program. Our CFO had been<br />

putting the program together, but now he had<br />

been informed that having a CFO heading<br />

up a compliance program was not going to be<br />

viewed as “a good thing.” That’s when I was<br />

asked to take over the task of getting a compliance<br />

program up and running across the<br />

various divisions of the hospital. He assured<br />

me that this was a time-limited project—that<br />

once the program was in place, it would pretty<br />

much take care of itself. Ten years later, as the<br />

Vice President of Corporate <strong>Compliance</strong>, I’m<br />

still trying to figure out how to finish the job!<br />

GW: Please describe the scope of your<br />

compliance responsibilities and your<br />

reporting process – both management and<br />

programmatically.<br />

<strong>BP</strong>: As Vice President of Corporate<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong>, I have a dual reporting relationship<br />

- as a member of senior management, I<br />

report directly to our CEO and I also have<br />

the authority to report directly to our Board<br />

of Trustees. Along with my compliance<br />

officer duties, I still have responsibilities over<br />

a couple of support services departments. In<br />

addition, I serve as our Privacy Officer and I<br />

oversee our contract management program.<br />

With the addition of a <strong>Compliance</strong> Assistant<br />

last spring, our <strong>Compliance</strong> department<br />

is now a two-person shop. It goes without<br />

saying that I rely heavily on the efforts of the<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

other members of our senior management<br />

team to make compliance work at RHI.<br />

Having such a strong leadership team to<br />

work with, a team that has truly taken the<br />

compliance discipline to heart, has been an<br />

amazing help to me. They carry a substantial<br />

part of the responsibility for the day-to-day<br />

maintenance of the compliance program, and<br />

without their support and assistance, my job<br />

would be impossible.<br />

Early on, our senior management team<br />

decided to emphasize the link between quality<br />

issues and compliance, so we’ve had quality<br />

elements as part of our annual <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

Work Plan for several years. That linkage was<br />

carried over to our governing body as well.<br />

The board formed a separate committee called<br />

the Personnel, <strong>Compliance</strong>, and Quality<br />

Committee (PCQ) to oversee those three<br />

areas. This has proven to be one of the more

prescient steps we’ve taken. When the emphasis<br />

on issues of quality intensified nationally,<br />

we were already well positioned at the governance<br />

level with a well-informed board committee<br />

that was ready and able to manage their<br />

increasing oversight responsibilities.<br />

I’m fortunate to have the opportunity to<br />

have significant levels of personal interaction<br />

with our board. I am chairman of our<br />

<strong>Compliance</strong> Committee and there is board<br />

representation on that committee. I make<br />

regular compliance reports to the PCQ<br />

Committee every month, and I attend the<br />

monthly board meetings, having scheduled<br />

time on their agenda quarterly to discuss<br />

compliance issues. Being allowed to have<br />

this amount of face time with our board is<br />

a reflection of just how committed they are<br />

to having a compliance program that is well<br />

grounded and effective. Whenever there is<br />

something new to be implemented or there<br />

is an evolving issue that RHI is confronting,<br />

getting the board’s support early on goes a<br />

long way to keeping things moving forward.<br />

GW: I understand Rutherford Hospital<br />

participated in the OIG Roundtable discussion<br />

regarding dashboards and quality indicators.<br />

Tell us a little about your journey to<br />

developing your dashboard and how you and<br />

your organization are using the information.<br />

<strong>BP</strong>: One of the unintended consequences<br />

of developing the PCQ reporting channel<br />

was the increasing amount of data that was<br />

being reported to that committee. When you<br />

consider all the regulatory requirements that<br />

have been added to the compliance umbrella<br />

in the last several years, add on all the issues<br />

related to quality and patient safety, and<br />

then mix in personnel matters and physician<br />

credentialing, the PCQ members ended up<br />

in the proverbial position of “drinking from<br />

a fire hose.” There is only so much information<br />

that can be taken in, and we found that<br />

the PCQ members were being overwhelmed<br />

with data. Ultimately, some sort of filtering<br />

process had to be put into place and that’s<br />

where the dashboard came into play.<br />

We had already developed a basic dashboard<br />

format for tracking issues reported to our<br />

Quality Management Committee, so that<br />

model served as the starting point for what later<br />

became our corporate dashboard. Our CFO has<br />

been instrumental in championing this effort<br />

over the last 18 months, and it has proven to be<br />

a much more complex process than one would<br />

imagine. Identifying what information should<br />

be on the dashboard was just the tip of the<br />

iceberg. We then had to identify what objective<br />

comparative benchmarks would be used, what<br />

reporting thresholds would be established,<br />

what sources of data would be used, what the<br />

reporting period intervals would be, who would<br />

be responsible for compiling the data, how<br />

would the accuracy of the data be ensured, how<br />

would differing lag times in data availability<br />

be handled, etc. But in the end, the dashboard<br />

is serving its purpose; it is focusing the PCQ<br />

member’s attention on not only our current<br />

status on important issues, but it is also allowing<br />

them to monitor trending over time – something<br />

that is critical when making decisions on<br />

the appropriate allocation of finite resources.<br />

GW: Tell us about the resources you find<br />

helpful for moving your program forward.<br />

<strong>BP</strong>: During my years as a nursing home<br />

administrator, I looked to national and state<br />

professional associations as my primary<br />

resources for information and education.<br />

When I became a compliance officer in 1998,<br />

the first thing I did was try to find a comparable<br />

professional organization that I could<br />

look to for help. That’s when I first became<br />

aware of HCCA, and I’ve depended on them<br />

ever since for resources that would help me be<br />

successful in my new role. I still have a well<br />

worn copy of The <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

Professional’s Manual sitting on my office shelf.<br />

It served me well when I was just getting<br />

Greg Warner<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Compliance</strong> <strong>Association</strong> • 888-580-8373 • www.hcca-info.org<br />

started and it served me well when I was preparing<br />

for my CHC credential.<br />

I‘ve attended at least one HCCA conference<br />

every year since 1998 and they have provided<br />

more than just food for thought. There is<br />

a real and obvious value in hearing what<br />

the leaders in our industry have to say<br />

about properly building and maintaining a<br />

compliance program. But to also hear directly<br />

from leaders of regulatory and enforcement<br />

agencies - to actually hear first hand their<br />

thoughts, concerns, and ideas – has provided<br />

just so much more value. The conferences also<br />

serve as my “early warning system” when new<br />

things are coming down the pipeline. RHI<br />

has a history of being an early adopter and<br />

that has proven to be true for our compliance<br />

program as well – thanks in large part to the<br />

contacts I’ve made through HCCA.<br />

GW: How do you see <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

evolving? That is, will we continue to integrate<br />

with Quality, Accreditation, Safety, etc.<br />

or should we be more stand–alone?<br />

<strong>BP</strong>: When I started in this field, <strong>Compliance</strong><br />

was truly only about coding and billing, and<br />

there was enough regulatory risk there (and<br />

still is) to go around. But now we all know<br />

that it’s not just coding and billing that can<br />

land your organization in the hot seat. A<br />

groundskeeper improperly disposing of excess<br />

Continued on page 16<br />

15<br />

March 2009

Meet Bill Parke ...continued from page 15<br />

pesticides can get you into an awful lot of<br />

difficulty, too. In an increasingly complex<br />

regulatory environment, the <strong>Compliance</strong> discipline<br />

we have honed over the years with its<br />

metrics of clear standards – responsible leadership,<br />

adequate training, internal controls,<br />

reporting mechanisms, and corrective action<br />

– are applicable across the entire enterprise.<br />

Our philosophy is to make our compliance<br />

program a resource for helping stakeholders<br />

manage regulatory risk wherever it is found<br />

– from EMTALA to disaster preparedness,<br />

from HIPAA to wage and hour laws.<br />

That doesn’t mean we “own” those operational<br />

processes, only that we assist those<br />

who do own them to manage them in a more<br />

consistent manner. For example, in the last<br />

couple years we found ourselves assisting in<br />

matters related to governance. Specifically,<br />

we helped our board incorporate certain<br />

elements of Sarbanes Oxley into their committee<br />

processes and we also helped establish<br />

a rebuttable presumption process to protect<br />

against excess benefit transactions. This year<br />

we’ll be keeping up with the work being<br />

done to comply with the new IRS Form 990<br />

reporting requirements and, relatedly, assisting<br />

in the refinement of the processes for the<br />

gathering and compiling of information that<br />