- Page 1 and 2: Absolute PC Security and Privacy Mi

- Page 3 and 4: infected files from his system. Som

- Page 5 and 6: You don’t have to read Absolute P

- Page 7: Unfortunately, this problem doesn

- Page 11 and 12: Some computer viruses are created w

- Page 13 and 14: Unfortunately, that’s a bit of a

- Page 15 and 16: Note In reality, you can create a v

- Page 17 and 18: The right tools include one of the

- Page 19 and 20: There’s still a danger of receivi

- Page 21 and 22: If your e-mail program is configure

- Page 23 and 24: The list starts with executable fil

- Page 25 and 26: .exe, you think you’re dealing wi

- Page 27 and 28: elatively easy to track down—and

- Page 29 and 30: You also increase your risk if you

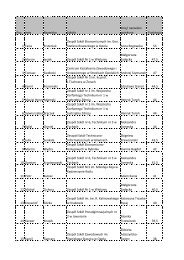

- Page 31 and 32: Table 2.2: Virus Risk Potential for

- Page 33 and 34: If you’ve ever been hit by a comp

- Page 35 and 36: Overview The two earliest forms of

- Page 37 and 38: Figure 3.2: The boot process as aff

- Page 39 and 40: Your PC is now Stoned! Further evid

- Page 41 and 42: OBJ, LIB, and Source Code Viruses A

- Page 43 and 44: Magistr This is a memory-resident p

- Page 45 and 46: While boot sector viruses are relat

- Page 47 and 48: • Microsoft Excel (XLS and XLW fi

- Page 49 and 50: For a period of time in the mid- to

- Page 51 and 52: exit the program. Since many macro

- Page 53 and 54: Overview As you learned in Chapter

- Page 55 and 56: Different Types of Script Viruses I

- Page 57 and 58: Does your name add up to 666 Enter

- Page 59 and 60:

Links This VBS worm sends itself as

- Page 61 and 62:

Win95.SK Win95.SK is a virus that,

- Page 63 and 64:

Figure 5.2 : Configuring Outlook Ex

- Page 65 and 66:

administrator. Disabling Scripting

- Page 67 and 68:

Attach the file to an e-mail from a

- Page 69 and 70:

situation. Indeed, most attackers u

- Page 71 and 72:

FREE SURF fwd: Joke Hello Kitty I C

- Page 73 and 74:

Figure 6.1 : The contents of a typi

- Page 75 and 76:

• PestPatrol (www.safersite.com)

- Page 77 and 78:

Common Worms The number of worms in

- Page 79 and 80:

Nimda Nimda was briefly discussed i

- Page 81 and 82:

type of worm from your computer sys

- Page 83 and 84:

(typically using Trojan techniques,

- Page 85 and 86:

(As you can see, HTML e-mail is ide

- Page 87 and 88:

If you never open any e-mail attach

- Page 89 and 90:

Virus Protection in Outlook Express

- Page 91 and 92:

Figure 7.6 : Disabling the Preview

- Page 93 and 94:

chat session, all other infected us

- Page 95 and 96:

In addition, most antivirus program

- Page 97 and 98:

You are infected with a virus that

- Page 99 and 100:

How to Remove an Instant Messaging

- Page 101 and 102:

when an individual takes an existin

- Page 103 and 104:

New Pictures of Family This virus h

- Page 105 and 106:

For example, the Naked Wife worm re

- Page 107 and 108:

This chapter also provides a look a

- Page 109 and 110:

Program Approx. Price Manual Disk &

- Page 111 and 112:

F-Prot Antivirus contains one of th

- Page 113 and 114:

Note Panda Antivirus Platinum is av

- Page 115 and 116:

Note Command on Demand is available

- Page 117 and 118:

Figure 9.2 : Scanning for viruses w

- Page 119 and 120:

Figure 9.5 : Configuring Norton's A

- Page 121 and 122:

6. When the Scan And Deliver Wizard

- Page 123 and 124:

Figure 9.8 : The results of a Virus

- Page 125 and 126:

Figure 9.10 : Configuring VirusScan

- Page 127 and 128:

Continue Scanning Records any infec

- Page 129 and 130:

To understand how new viruses show

- Page 131 and 132:

Figure 10.2 : How integrity checkin

- Page 133 and 134:

Figure 10.4 : How sandboxing identi

- Page 135 and 136:

obsessive about this sort of thing,

- Page 137 and 138:

look at a list of files in My Compu

- Page 139 and 140:

software is more deliberate, and it

- Page 141 and 142:

Your antivirus program will also sc

- Page 143 and 144:

Update Your E-mail Program Everythi

- Page 145 and 146:

• Virus Alerts Mailing List (www.

- Page 147 and 148:

While we're on the topic of switchi

- Page 149 and 150:

To further reduce your risk of infe

- Page 151 and 152:

4. Go online to your antivirus soft

- Page 153 and 154:

General File Cleaning When you run

- Page 155 and 156:

Once you know which files you need

- Page 157 and 158:

Reinstalling System Files Unfortuna

- Page 159 and 160:

of the attacker to do specific harm

- Page 161 and 162:

One reason for the recent increase

- Page 163:

How to Initiate a Computer Attack H

- Page 166 and 167:

On the morning of February 7th, the

- Page 168 and 169:

It's likely that you'll first notic

- Page 170 and 171:

• Activate password protection to

- Page 172 and 173:

The people who attack computers in

- Page 174 and 175:

impersonation attack is always limi

- Page 176 and 177:

Note The following are relatively t

- Page 178 and 179:

data stream and 'becoming' one of t

- Page 180 and 181:

As you learned in Chapter 11, 'Prev

- Page 182 and 183:

That's because the longer you're on

- Page 184 and 185:

Start by reconfiguring Windows for

- Page 186 and 187:

If this is too extreme a measure, y

- Page 188 and 189:

Computer theft is a particular prob

- Page 190 and 191:

typical P2P connection. No servers,

- Page 192 and 193:

and search for 'Weezer.' You then s

- Page 194 and 195:

Instant messaging presents a unique

- Page 196 and 197:

And that's not the only security pr

- Page 198 and 199:

your permission if you accept the '

- Page 200 and 201:

Security Risks-On the Other End Unl

- Page 202 and 203:

• Firewall software • Firewall

- Page 204 and 205:

either inside the firewall or repla

- Page 206 and 207:

crackers on drive-by "war runs" to

- Page 208 and 209:

Figure 18.3 : Filtering incoming tr

- Page 210 and 211:

80. Your firewall, then, can be con

- Page 212 and 213:

state, recorded during installation

- Page 214 and 215:

distributes ZoneAlarm Pro, for abou

- Page 216 and 217:

Figure 18.7 : Configuring the Inter

- Page 218 and 219:

Figure 18.10 : Viewing recent attac

- Page 220 and 221:

Figure 18.13 : Configuring firewall

- Page 222 and 223:

Despite your best precautions, you

- Page 224 and 225:

Figure 19.1 : Using Windows XP's Se

- Page 226 and 227:

the signatures of known intrusion t

- Page 228 and 229:

We Americans value our privacy. We

- Page 230 and 231:

It also reinforces the general warn

- Page 232 and 233:

User Profiling What good is all thi

- Page 234 and 235:

Tip If you can't find a site's priv

- Page 236 and 237:

Yahoo! automatically receives and r

- Page 238 and 239:

Figure 20.1 : Look for these seals

- Page 240 and 241:

Whether these activities are permis

- Page 242 and 243:

Of course, if you're one of the cor

- Page 244 and 245:

• Buy personal information from '

- Page 246 and 247:

• For any credit card, loan, or b

- Page 248 and 249:

• Any U.S. attorney or state atto

- Page 250 and 251:

When you want to protect your priva

- Page 252 and 253:

There are many ways you can be defr

- Page 254 and 255:

situation. The simple fact is that

- Page 256 and 257:

Another potential area of online fr

- Page 258 and 259:

feedback. You can also read the ind

- Page 260 and 261:

Money Orders and Cashier's Checks A

- Page 262 and 263:

The Nigerian Letter scam started ou

- Page 264 and 265:

• If you think your bank accounts

- Page 266 and 267:

And stalking can lead to worse offe

- Page 268 and 269:

It can also be dangerous. Many stal

- Page 270 and 271:

How to Protect Your Children Online

- Page 272 and 273:

Spyware is like a Trojan horse, in

- Page 274 and 275:

visited. This information is then r

- Page 276 and 277:

In many ways, this is like a tradit

- Page 278 and 279:

Using Antispy Software An easier wa

- Page 280 and 281:

Spyware that is installed and used

- Page 282 and 283:

Cookie Management The reason you pr

- Page 284 and 285:

You can also adjust the privacy lev

- Page 286 and 287:

Figure 24.5 : Removing stored cooki

- Page 288 and 289:

Read on to learn more about these r

- Page 290 and 291:

they’re easier to remember. If yo

- Page 292 and 293:

Note The RSA cryptography algorithm

- Page 294 and 295:

Fortunately, Outlook Express automa

- Page 296 and 297:

Fortunately, we can use digital tec

- Page 298 and 299:

Personal Digital IDs for e-mail can

- Page 300 and 301:

Some possible forms of biometric id

- Page 302 and 303:

Figure 26.1 : Making Web page reque

- Page 304 and 305:

• Stealther (www.photono-software

- Page 306 and 307:

“dummy” IDs, messages can still

- Page 308 and 309:

communities, if you will. These fre

- Page 310 and 311:

subscribe to on a regular basis. Tw

- Page 312 and 313:

Figure 27.1 : A plain-text spam mes

- Page 314 and 315:

The problems posed by these types o

- Page 316 and 317:

So all those e-mails you get from L

- Page 318 and 319:

as to be virtually unusable.) Spamm

- Page 320 and 321:

For this reason, many individuals a

- Page 322 and 323:

Probably the easiest way to obtain

- Page 324 and 325:

Don’t Unsubscribe You should also

- Page 326 and 327:

o o 4. Click Summary. 5. Click Save

- Page 328 and 329:

If you’re resigned to the fact th

- Page 330 and 331:

At the same time, create a second,

- Page 332 and 333:

On the national level, the FTC has

- Page 334 and 335:

But in an age where too many Intern

- Page 336 and 337:

Ms. Fonda did visit North Vietnam i

- Page 338 and 339:

which exploded and burned down her

- Page 340 and 341:

Nigerian Letter Scam Probably the m

- Page 342 and 343:

typical Web page. In addition, the

- Page 344 and 345:

(You can change the width and heigh

- Page 346 and 347:

4. Scroll down to the Scripting sec

- Page 348 and 349:

Because banner ads are just graphic

- Page 350 and 351:

Sometimes you open e-mail ads witho

- Page 352 and 353:

Of course, forced frames aren’t t

- Page 354 and 355:

To this end, there are several orga

- Page 356 and 357:

to filter out some degree of legiti

- Page 358 and 359:

Figure 31.3 : Configuring Internet

- Page 360 and 361:

OneKey OneKey (www.onekey.com) is a

- Page 362 and 363:

authentication The process of deter

- Page 364 and 365:

An electronic credential that confi

- Page 366 and 367:

IP half scan A type of pre-attack p

- Page 368 and 369:

A secret key that can be used, eith

- Page 370:

An attack resulting from the attack