Big Brown Bat Eptesicus fuscus (Beauvois, 1796) - College of Forest ...

Big Brown Bat Eptesicus fuscus (Beauvois, 1796) - College of Forest ...

Big Brown Bat Eptesicus fuscus (Beauvois, 1796) - College of Forest ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MAMMALS OF MISSISSIPPI 5:1–8<br />

<strong>Big</strong> brown bat (<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>)<br />

ALISHA A. WORKMAN<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi, 39762, USA<br />

Abstract—<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> (<strong>Beauvois</strong>, <strong>1796</strong>) is a vespertilionine commonly called the big brown bat.<br />

It is sexually dimorphic with the female being slightly larger than the male. Dorsal color ranges from<br />

pinkish tan to rich chocolate and the ventral color ranges from pink to olive buff. It represents one<br />

out <strong>of</strong> twenty four in the genus <strong>Eptesicus</strong>. <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> is distributed through all <strong>of</strong> the United<br />

States except Hawaii, most <strong>of</strong> Central America except the Yucatan Peninsula, and its southern limit is<br />

northwestern South America. <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> generally prefers to live in caves, trees, bridges, and<br />

buildings. <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> is currently not listed as a species <strong>of</strong> special concern.<br />

Published 5 December 2008 by the Department <strong>of</strong> Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University<br />

<strong>Big</strong> <strong>Brown</strong> <strong>Bat</strong><br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> (<strong>Beauvois</strong>, <strong>1796</strong>)<br />

CONTEXT AND CONTENT.<br />

Order Chiroptera, Suborder Microchiroptera,<br />

Family Vespertilionidae, Subfamily<br />

Vespertilioninae, Tribe Vespertilionini.<br />

GENERAL CHARACTERS<br />

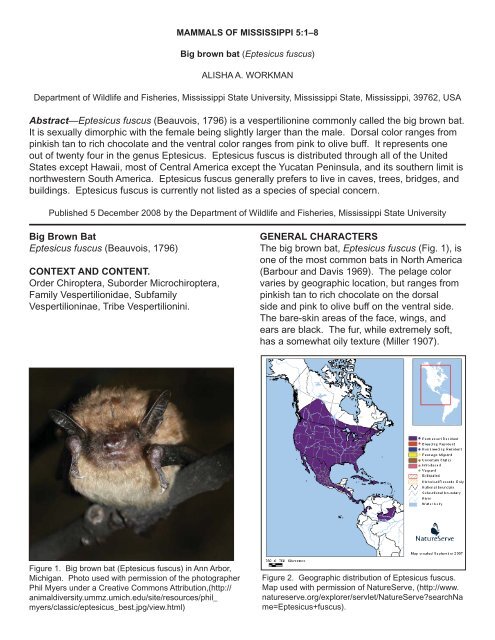

The big brown bat, <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> (Fig. 1), is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the most common bats in North America<br />

(Barbour and Davis 1969). The pelage color<br />

varies by geographic location, but ranges from<br />

pinkish tan to rich chocolate on the dorsal<br />

side and pink to olive buff on the ventral side.<br />

The bare-skin areas <strong>of</strong> the face, wings, and<br />

ears are black. The fur, while extremely s<strong>of</strong>t,<br />

has a somewhat oily texture (Miller 1907).<br />

Figure 1. <strong>Big</strong> brown bat (<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>) in Ann Arbor,<br />

Michigan. Photo used with permission <strong>of</strong> the photographer<br />

Phil Myers under a Creative Commons Attribution,(http://<br />

animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/resources/phil_<br />

myers/classic/eptesicus_best.jpg/view.html)<br />

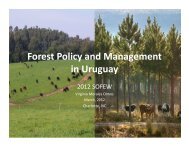

Figure 2. Geographic distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>.<br />

Map used with permission <strong>of</strong> NatureServe, (http://www.<br />

natureserve.org/explorer/servlet/NatureServesearchNa<br />

me=<strong>Eptesicus</strong>+<strong>fuscus</strong>).

DISTRIBUTION<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> occurs throughout a large<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> North and Central America and as far<br />

south as northwestern South America (Fig. 2).<br />

It also resides in Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico<br />

(Hall 1981), and some <strong>of</strong> the Bahama Islands<br />

(Buden 1985). The big brown bat occurs<br />

throughout the United States except Hawaii<br />

(Hall 1981) and in Mexico except the Yucatan<br />

Peninsula (Buden 1985). Although there are 11<br />

subspecies <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>fuscus</strong> (Neubaum et. al 2007),<br />

only E. <strong>fuscus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> occurs in Mississippi (Hall<br />

1981).<br />

Figure 3. Dorsal, ventral and lateral views <strong>of</strong> the skull<br />

and a lateral view <strong>of</strong> the mandible <strong>of</strong> an adult female<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> in Lexington, Massachusetts. Greatest<br />

length <strong>of</strong> the skull is 18.2 mm. Drawings by J. Love.<br />

Measurements (in mm) <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>fuscus</strong> are: total<br />

length, 87–138; length <strong>of</strong> tail vertebrae, 34–57;<br />

length <strong>of</strong> hind foot, 8–14; length <strong>of</strong> ear from<br />

notch, 10–20; length <strong>of</strong> tragus, 6–10; length<br />

<strong>of</strong> forearm, 39-54; length <strong>of</strong> third metacarpal,<br />

43-50; length <strong>of</strong> tibia, 17-21; greatest length<br />

<strong>of</strong> skull, 15.1–23.0 (Fig.3); zygomatic breadth,<br />

11.1–14.2; breadth <strong>of</strong> braincase, 7.5–9.6;<br />

length <strong>of</strong> maxillary toothrow, 7.0–9.8. Adults<br />

typically weigh 11-23g. This species is sexually<br />

dimorphic, with females slightly larger than<br />

males (Burnett 1983a). The big brown bat and<br />

the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) are the only<br />

vespertilionids that produce an audible sound<br />

during fl ight. Wing and skull size is positively<br />

correlated with the amount <strong>of</strong> environmental<br />

moisture (Burnett 1983b).<br />

FORM AND FUNCTION<br />

Form.—Each June, <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> molts by<br />

shedding its winter coat (Phillips 1966). The<br />

dental formula is i 2/3, c 1/1, p 1/2, m 3/3, total<br />

32. The crowns on M1 and M2 are narrower<br />

than those <strong>of</strong> M3. The two pectoral mammae<br />

contain milk that contains 2.5% lactose, 6.2%<br />

protein, and 16.4% fat (Kunz et. al 1983).<br />

This species displays pararhinal glands on<br />

the sides <strong>of</strong> the nose that consist <strong>of</strong> apocrine<br />

tubules (for producing sweat), which set atop<br />

sebaceous units (Dapson et. al 1977). The red<br />

blood cell count is 11.96 x 106/mL (Dunaway<br />

and Lewis 1965). The bones that make up<br />

the right and left appendages weigh the same,<br />

which indicates that E. <strong>fuscus</strong> is ambidextrous<br />

(Dawson 1975). Polydactyly, deformed<br />

vertebrae, and underdeveloped radii are a<br />

few <strong>of</strong> the skeletal anomalies that can occur<br />

in this species (Kunz and Chase 1983). Over<br />

time, this species has lost the ceratohyal <strong>of</strong> the<br />

hyoid (Griffi ths 1983). The baculum is about<br />

0.8 mm long (Hamilton 1949). E. <strong>fuscus</strong> will<br />

defecate within 90–130 minutes <strong>of</strong> eating. It<br />

will completely pass a meal within 24 hours <strong>of</strong><br />

eating (Luckens et. al 1971).<br />

Function.—The big brown bat has a large<br />

heart that can represent 0.9% <strong>of</strong> its fat-free<br />

body mass. The resting heart rate is about 450<br />

beats/min. During fl ight, the heart rate more<br />

than doubles to about 1,022 beats/min (Studier<br />

and Howell 1969). During torpor, the heart<br />

rate dramatically drops between 4–62 beats/<br />

min. After arousal from hibernation, the heart<br />

rate increases from 12–800 beats/min (Rauch<br />

1973).

Rhodopsin and an unidentifi ed molecule are<br />

the two photopigments in the retina (Kurta<br />

and Baker 1990). A few ocular abnormalities<br />

are known to occur, such as an unpigmented<br />

choroid, undifferentiated retina, and<br />

underdeveloped lenses (Kunz and Chase<br />

1983).<br />

When the ambient temperature is 10 years; the oldest recorded age<br />

is 19 years (Paradiso and Greenhall 1967).<br />

Males live longer than females. Males occur at<br />

higher elevations in mountainous regions than<br />

females (Kurta and Baker 1990). Postnatal<br />

mortality before weaning is 7–10%. In adults,<br />

common mortality factors are predation, failure<br />

to store enough fat for hibernation, accidents,<br />

and inclement weather.<br />

Space use.—<strong>Bat</strong>-habitat relationships can<br />

be very complicated due to their high mobility.<br />

Therefore, studies have failed to quantify<br />

habitat requirements <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>.<br />

However, this species occurs in both urban<br />

and rural areas. Night roosts are frequently in<br />

locations that allow it to forage and engage in<br />

social interactions. <strong>Big</strong> brown bats frequently<br />

use buildings as roosts, <strong>of</strong>ten near a light where<br />

insect densities are likely higher. They will also<br />

roost in caves, tunnels, mines, tree cavities,<br />

rock crevices, and under bridges (Agosta,<br />

2002). They seldom move farther than 80 km<br />

between their summer and winter roosts (Kurta<br />

and Baker 1990).

Diet.—<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> is insectivorous<br />

(Agosta 2002). <strong>Big</strong> brown bats are also<br />

generalists and do not have a preference for<br />

over-water versus over-land foraging sites.<br />

They begin foraging within an hour after<br />

sunset and spend an average <strong>of</strong> 100 min/night<br />

foraging. Prey varies by geographic location<br />

but generally consists <strong>of</strong> beetles, moths,<br />

mosquitoes and dragonfl ies (Kurta and Baker<br />

1990).<br />

Diseases and parasites.—There are many<br />

ectoparasites known to affect <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong><br />

including Cimex (bedbugs), Basilia (bat fl ies),<br />

Ornithodoros (s<strong>of</strong>t ticks), Leptotrombidium<br />

(chigger mites), and Myodopsylla (bat fl eas)<br />

(Kurta and Baker 1990). One species <strong>of</strong><br />

rosensteiniid mite,Nycteriglyphus <strong>fuscus</strong>, lives<br />

in the guano <strong>of</strong> E. <strong>fuscus</strong> (Dood and Rockett<br />

1985). To avoid ectoparasites, female big<br />

brown bats may frequently change roost sites<br />

(Agosta 2002).<br />

Many endoparasites are also known to affect<br />

E. <strong>fuscus</strong>, including nematodes from the<br />

genera Allintoshius, Cyrnea, Physocephalus,<br />

and Capillaria. Maseria vespertilionis is a<br />

nematode that only infects the subcutaneous<br />

tissue in the plantar surface <strong>of</strong> the bat’s feet.<br />

Females that roost in colonies are frequently<br />

infected whereas males are not. <strong>Big</strong> brown<br />

bats are also infected with cestodes such<br />

as Hymenolepis (tapeworms). Parasitic<br />

trematodes include Dicrocoelium (liver fl ukes),<br />

Limatulum, and Glyptoporus (Kurta and Baker<br />

1990).<br />

The big brown bat is a vector for St. Louis<br />

encephalitis. A mosquito will bite an infected<br />

bat and then bite a human, which is how the<br />

virus is transmitted (Herbold et. al 1983).<br />

Histoplasma capsulatum, a fungus, is found<br />

in the big brown bat’s tissues and guano.<br />

This fungus causes histoplasmosis (Darling’s<br />

disease) in humans, cats, and dogs, which<br />

affects the lungs (Bartlett et. al 1982).<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> is known to carry rabies<br />

throughout the United States (Trimarchi and<br />

Debbie 1977). However, local epizootics are<br />

rare (Kurta 1979; Pybus 1986). In this species,<br />

rabies infects the brain, brown fat, and salivary<br />

glands (Kurta and Baker 1990) but is not<br />

transmitted across the placenta (Constantine<br />

1986). Incubation <strong>of</strong> the disease has been<br />

observed to last up to 209 days (Moore and<br />

Raymond 1970).<br />

Interspecific interactions.—Common<br />

predators include common grackles, longtailed<br />

weasels, various owl species, house<br />

cats, and bullfrogs. Interspecifi c competition<br />

in foraging areas is known to occur between<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> and Lasionycteris noctivagans<br />

(silver-haired bat), as well as Chordeiles minor<br />

(common night hawk). However, the extent to<br />

which these interactions occur in Mississippi<br />

is not known (Reith 1980). Intraspecifi c<br />

competition occurs at highly aggressive levels<br />

but the signifi cance <strong>of</strong> these events is unknown<br />

(Kurta and Baker 1990).<br />

BEHAVIOR<br />

Infant big brown bats will sound an “isolation<br />

call” that can be heard from about 10 m away<br />

when they are separated from their mothers<br />

or fall from the nest. Females respond with<br />

an ultrasonic chirping noise (Gould 1971).<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> has demonstrates a 24-hr<br />

behavior rhythm that is persistent but inexact<br />

(Twente and Twente 1987). <strong>Big</strong> brown bats<br />

can use olfactory cues to distinguish among<br />

individual colony members as well as between<br />

young in a maternity colony, which may reduce<br />

agonistic interactions (Boss et. al 2002).<br />

Decreasing ambient temperature appears to<br />

trigger hibernation in big brown bats. While<br />

both the males and females will deposit fat in<br />

anticipation <strong>of</strong> hibernation, females deposit fat<br />

about one month earlier than males (Pistole<br />

1988). Although females begin fat deposition<br />

earlier, males enter hibernation fi rst (Phillips<br />

1966). <strong>Big</strong> brown bats typically hibernate at<br />

ambient temperatures below freezing (Barbour<br />

and Davis 1969), using rock crevices, caves,<br />

old buildings, and mines as hibernacula (Mills<br />

et. al 1975). Most big brown bats do not<br />

hibernate in colonies, but small groups are<br />

common (Mumford 1958).

Female big brown bats will usually form<br />

large maternity colonies in trees, caves, and<br />

buildings to give birth and raise their young.<br />

By doing so, thermoregulation costs go down<br />

which is important as stable temperatures are<br />

vital for proper development <strong>of</strong> young (Boss<br />

et. al 2002). They also take advantage <strong>of</strong><br />

cooperative foraging to reduce energy spent<br />

searching for prey. Also, individual predation<br />

risks may be lower in the colonies (Willis and<br />

Brigham 2004).<br />

CONSERVATION<br />

The IUCN lists the big brown bat as a species<br />

<strong>of</strong> least concern which means it is not in<br />

danger <strong>of</strong> becoming threatened or endangered<br />

(IUCN 2007). They are, however, ‘critically<br />

imperiled’ in Louisiana. <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong> are<br />

important members <strong>of</strong> the ecosystems in which<br />

they live. They are primary insect consumers,<br />

which fi lls an important ecological niche. Also,<br />

pesticides and other man-made chemicals<br />

increasingly pose threats to E. <strong>fuscus</strong> (Agosta<br />

2002).<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

I wish to thank my pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr. J. Belant for<br />

his help with this project, as well as my fellow<br />

peers who served as editors. I also wish<br />

to thank the staff <strong>of</strong> the Mitchell Memorial<br />

Library and the <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> Resources<br />

at Mississippi State University for assistance<br />

in gaining access to valuable information and<br />

materials.

LITERATURE CITED<br />

Agosta, S. J. 2002. Habitat use, diet and<br />

roost selection by the big brown<br />

bat (<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>). Mammal Review<br />

32(2):179–198.<br />

Barbour, R. W., and W. H. Davis. 1969. <strong>Bat</strong>s<br />

<strong>of</strong> America. University Press Kentucky,<br />

Lexington 286 pages.<br />

Bartlett, P. C., L. A. Vonbehren, R. P. Tewari, R.<br />

J. Martin, L. Eagleton, M. J. Isaac, and<br />

P. S. Kulkarni. 1982. <strong>Bat</strong>s in the belfry:<br />

an outbreak <strong>of</strong> histoplasmosis. American<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Public Health 72:1369–1372.<br />

Birney, E. C. and D. D. Baird. 1985. Why do<br />

some mammals polyovulate to produce<br />

a litter <strong>of</strong> two The American Naturalist<br />

126:136–140.<br />

Boss, J., T. E. Acree, J. M. Bloss, W. R.<br />

Hood, and T. H. Kunz. 2002. Potential<br />

use <strong>of</strong> chemical cues for colony-mate<br />

recognition in the big brown bat,<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>. Journal <strong>of</strong> Chemical<br />

Ecology 28(4):819–834.<br />

Buden, D. W. 1985. Additional records <strong>of</strong> bats<br />

from the Bahama Islands. Caribbean<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Science 21:19–25.<br />

Burnett, C. D. 1983a. Geographic variation<br />

and sexual dimorphism in the<br />

morphology <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>. Annals<br />

<strong>of</strong> Carnegie Museum 52:139–162.<br />

Burnett, C. D. 1983b. Geographic and<br />

climate correlates <strong>of</strong> morphological<br />

variation in <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Mammalogy 64:437–444.<br />

Burnett, C. D., and T. H. Kunz. 1982. Growth<br />

rates and age estimation in <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong> and comparison with Myotis<br />

lucifugus. Journal <strong>of</strong> Mammalogy<br />

63:33–41.<br />

Constantine, D. G. 1986. Absence <strong>of</strong> prenatal<br />

infection <strong>of</strong> bats with rabies virus.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Wildlife Diseases 22:249–250.<br />

Dapson, R. W., E. H. Studier, J. Buckingham,<br />

and A. L. Studier. 1977. Histology <strong>of</strong><br />

odoriferous secretions from<br />

integumentary glands in three species <strong>of</strong><br />

bats. Journal <strong>of</strong> Mammalogy 58: 531–<br />

535.<br />

Dawson, D. L. 1975. Ambedexterity in bat<br />

wings as evidenced by bone weight.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Anatomy 120: 289–293.<br />

Dood, S. B., and C. L. Rockett. 1985.<br />

Nycteriglyphus <strong>fuscus</strong> (Acari:<br />

Rosensteiniidae), a new species<br />

associated with big brown bats in Ohio.<br />

International Journal <strong>of</strong> Acarology 11:31–<br />

35.<br />

Dunaway, P. B. and L. L. Lewis. 1965.<br />

Taxonomic relation <strong>of</strong> erythrocyte count,<br />

mean corpuscular volume, and body<br />

weight in mammals. Nature 205:481-<br />

484.<br />

Gould, E. 1971. Studies <strong>of</strong> maternalinfant<br />

communication and development<br />

<strong>of</strong> vocalizations in the bats Myotis and<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong>. Communications in<br />

Behavioral Biology 5:263–313.<br />

Griffi ths, T. A. 1983. Comparative laryngeal<br />

anatomy <strong>of</strong> the big brown bat, <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong>, and the mustached bat,<br />

Pteronotus parnellii. Mammalia 47:375–<br />

394.<br />

Hall, E. R. 1981. The mammals <strong>of</strong> North<br />

America. Second ed. John Wiley and<br />

Sons, New York, 1:1–600.<br />

Hamilton, W. J., Jr. 1949. The bacula <strong>of</strong> some<br />

North American vespertilionid bats.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Mammalogy 30:97–102.<br />

Herbold, J. R., W. P. Heuschele, R. L. Berry,<br />

and M. A. Parsons. 1983. Reservoir<br />

<strong>of</strong> St. Louis encephalitis virus in Ohio<br />

bats. American Journal <strong>of</strong> Veterinary<br />

Research 44:1889–1893.<br />

Herreid, C. F., II, and K. Schmidt-Nielsen.<br />

1966. Oxygen consumption,<br />

temperature, and water loss in bats from<br />

different environments. American<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Physiology 211:1108–1112.<br />

International Union for Conservation <strong>of</strong> Nature<br />

and Natural Resources. 2007. 2007<br />

IUCN Red list <strong>of</strong> threatened species.<br />

www.iucnredlist.org, accessed 27<br />

September 2008.<br />

Kluger, M. J., and J. E. Heath. 1970.<br />

Vasomotion in the bat wing: a<br />

thermoregulatory response to internal<br />

heating. Comparative Biochemistry and<br />

Physiology 32:219–226.

Kunz, T. H., and J. Chase. 1983. Osteological<br />

and ocular anomalies in juvenile big<br />

brown bats (<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>).<br />

Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong> Zoology 61:365–<br />

369.<br />

Kunz, T. H., M. H. Stack, and R. Jenness.<br />

1983. A comparison <strong>of</strong> milk composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> Myotis lucifugus and <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong>. Biology <strong>of</strong> Reproduction<br />

28:229–234.<br />

Kurta, A. 1979. <strong>Bat</strong> rabies in Michigan.<br />

Michigan Academician 12:221–230.<br />

Kurta, A. and R. H. Baker. 1990. <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong>. Mammalian Species No. 356.<br />

pp 1–10.<br />

Luckens, M. M., J. Van Eps, and W. H. Davis.<br />

1971. Transit time <strong>of</strong> food through the<br />

digestive tract <strong>of</strong> the bat, <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong>. Experimental Medicine and<br />

Surgery 29:25–28.<br />

Miller, G. S., Jr. 1907. The families and genera<br />

<strong>of</strong> bats. Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the United States<br />

National Museum 57:1–282.<br />

Mills, R. S., G. W. Barrett, and M. P. Farrell.<br />

1975. Population dynamics <strong>of</strong> the big<br />

brown bat (<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>) in<br />

southwestern Ohio. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Mammalogy 56:591–604.<br />

Moore, G. J., and H. Raymond. 1970.<br />

Prolonged incubation period <strong>of</strong> rabies<br />

in a naturally infected bat <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong> (<strong>Beauvois</strong>). The Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Wildlife Diseases 6:167–168.<br />

Mumford, R. E. 1958. Population turnover<br />

in wintering bats in Indiana. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Mammalogy 39:253–261.<br />

Neubaum, M. A., M. R. Douglas, M. E. Douglas,<br />

and T. J. O’Shea. 2007. Molecular<br />

ecology <strong>of</strong> the big brown bat (<strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong>): Genetic and natural history<br />

variation in a hybrid zone. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Mammalogy 88(5):1230–1238.<br />

Paradiso, J. L., and A. M. Greenhall. 1967.<br />

Longevity records for American bats.<br />

The American Midland Naturalist<br />

78:251–252.<br />

Phillips, G. L. 1966. Ecology <strong>of</strong> the big brown<br />

bat in Northeastern Kansas. The<br />

American Midland Naturalist 75:168–<br />

198.<br />

Pistole, D. H. 1988. Sexual differences in<br />

the annual lipid cycle <strong>of</strong> the big brown<br />

bat, <strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>. Canadian Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Zoology 67:1891–1894.<br />

Pybus, M. J. 1986. Rabies in insectivorous<br />

bats <strong>of</strong> western Canada, 1979–1983.<br />

The Journal <strong>of</strong> Wildlife Diseases 22:307–<br />

313.<br />

Rauch, J. C. 1973. Sequential changes in<br />

regional distribution <strong>of</strong> blood in <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong> (big brown bat) during arousal<br />

from hibernation. Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Zoology 51:973–981.<br />

Reith, C. C. 1980. Shifts in times <strong>of</strong> activity<br />

by Lasionycteris noctivagans. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Mammalogy 61:104–108.<br />

Sanderson, M. I., and J. A. Simmons.<br />

2005. Target representation <strong>of</strong><br />

naturalistic echolocation sequences in<br />

single unit responses from the inferior<br />

colliculus <strong>of</strong> big brown bats. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

the Acoustical Society <strong>of</strong> America<br />

118(5):3352–3361.<br />

Studier, E. H. and D. J. Howell. 1969. Heart<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> female big brown bats in fl ight.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Mammalogy 50: 842–845.<br />

Trimarchi, C. V., and J. G. Debbie. 1977.<br />

Naturally occurring rabies virus and<br />

neutralizing antibody in two species <strong>of</strong><br />

insectivorous bats <strong>of</strong> New York State.<br />

The Journal <strong>of</strong> Wildlife Diseases 3:366–<br />

369.<br />

Twente, J. W., and J. Twente. 1987.<br />

Biological alarm clock arouses<br />

hibernating big brown bats, <strong>Eptesicus</strong><br />

<strong>fuscus</strong>. Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong> Zoology<br />

65:1668–1674.<br />

Willis, C. K., and R. M. Brigham. 2004. Roost<br />

switching, roost sharing and social<br />

cohesion: forest-dwelling big brown bats,<br />

<strong>Eptesicus</strong> <strong>fuscus</strong>, conform to the fi ssion–<br />

fusion model. Animal Behavior 68:495–<br />

505.<br />

Contributing editor <strong>of</strong> this account was<br />

Clinton Smith.