Byron Flora and Fauna Study 1999 - Byron Shire Council

Byron Flora and Fauna Study 1999 - Byron Shire Council

Byron Flora and Fauna Study 1999 - Byron Shire Council

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

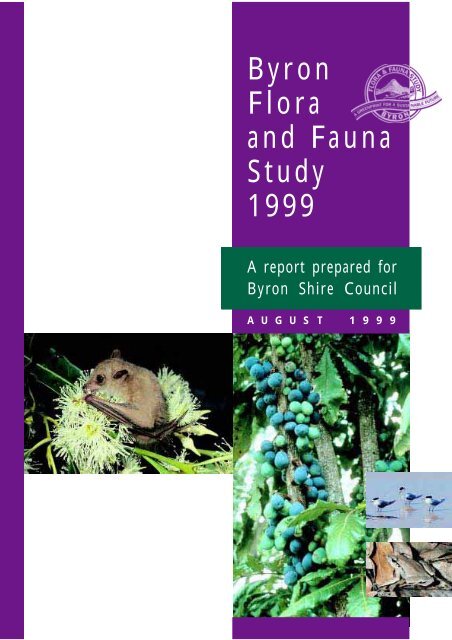

<strong>Byron</strong><br />

<strong>Flora</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong><br />

<strong>Study</strong><br />

<strong>1999</strong><br />

A report prepared for<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

A U G U S T 1 9 9 9

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

<strong>Byron</strong><br />

<strong>Flora</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong><br />

<strong>Study</strong><br />

<strong>1999</strong><br />

A U G U S T 1 9 9 9<br />

A report prepared for<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong> by:<br />

L<strong>and</strong>mark Ecological Services Pty Ltd<br />

(A.C.N. 064 548 876)<br />

PO Box 100<br />

Suffolk Park, NSW 2480<br />

Phone/fax: 02 6685 4430 or 02 6684 0127<br />

email: l<strong>and</strong>mark@nrg.com.au<br />

Ecograph<br />

Ecological <strong>and</strong> Geographical Information<br />

Systems Consultants<br />

Limpinwood Valley Rd<br />

Limpinwood via Murwillumbah NSW 2484<br />

Phone: 02 6679 3479<br />

Fax: 02 6679 3419<br />

email: info@ecograph.com.au<br />

Terrafocus Pty Ltd<br />

PO Box 694<br />

Mullumbimby NSW 2482<br />

Phone: 02 6684 0073<br />

email: terrafocus@bigpond.com.au<br />

1

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>1999</strong><br />

August <strong>1999</strong><br />

ISBN: 0 9588294 8 9<br />

© <strong>1999</strong> <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

PO Box 219, Mullumbimby NSW Australia 2482<br />

Phone: +61-2-6626 7000 Fax: +61-2-6684 3018<br />

E-mail: council@byron.nsw.gov.au<br />

This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part may be<br />

reproduced without permission from <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong>.<br />

Copyright to photographs remains with the photographers.<br />

Produced by Environmental Planning Services, <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Designed <strong>and</strong> typeset in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> by Gatya Kelly, Doric Order, The Pocket<br />

Imageset in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> by Graphic Expressions, <strong>Byron</strong> Bay<br />

Printed in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> by Keith Dubber Printing, Mullumbimby<br />

Cover photography of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> flora <strong>and</strong> fauna:<br />

Common Blossom-bat Syconycteris australis by: D.R. Milledge<br />

Davidson’s Plum Davidsonia pruriens var. jerseyana by: H.R.W. Nicholson<br />

Crested Tern Sterna bergii by: D.R. Milledge<br />

Fletcher’s Frog Lechriodus fletcheri by: D.R. Milledge<br />

Copies of this document may be purchased from <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong> at the above address<br />

Disclaimer<br />

Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, expressed or implied in this publication is made in good<br />

faith but on the basis that <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong>, its agents, consultants <strong>and</strong> employees are not liable (whether<br />

by reason of negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person for damage or loss whatsoever which has<br />

occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking (as the case may be) action in respect<br />

of any representation, statement or advice referred to above.<br />

2

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

Contents<br />

List of appendices 6<br />

List of tables 6<br />

List of maps 7<br />

List of figures 7<br />

List of photographs 8<br />

The project team 9<br />

Acknowledgements 10<br />

Mayor’s foreword 11<br />

Director’s comments 12<br />

Executive summary 13<br />

1 Introduction 17<br />

1.1 Background 17<br />

1.2 <strong>Study</strong> area 17<br />

1.3 On-going processes 18<br />

2 The environment of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 19<br />

2.1 Location <strong>and</strong> physiography 19<br />

2.1.1 Coastline 19<br />

2.1.2 Coastal Plain 19<br />

2.1.3 Coastal ridges 19<br />

2.1.4 Undulating volcanic plateau 20<br />

2.1.5 Mountain ranges <strong>and</strong> valleys 20<br />

2.2 Climate, temperature, rainfall <strong>and</strong> seasonality 20<br />

2.3 L<strong>and</strong> tenure, protected areas 20<br />

2.4 Geology <strong>and</strong> soils 21<br />

2.5 <strong>Flora</strong> 22<br />

2.6 <strong>Fauna</strong> 22<br />

3 Databases <strong>and</strong> GIS as basis for data management 24<br />

3.1 Introduction 24<br />

3.2 Geographical Information Systems (GIS) 24<br />

3.3 Field survey database 25<br />

3.4 <strong>Study</strong> outcomes 25<br />

3.5 Database management 25<br />

3.6 Future directions 25<br />

4 Vegetation mapping 27<br />

4.1 Introduction 27<br />

4.2 Previous studies 28<br />

4.3 Recommendations for <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> 28<br />

4.4 Methods 28<br />

4.4.1 Aerial Photographic Interpretation 28<br />

Photography 29; Photo preparation 29; API pathway 29; Minimum polygon size 30;<br />

Vegetation communities <strong>and</strong> associations 30; Crown Cover Percentage 30; Percentage of<br />

(soft) weed <strong>and</strong> pasture 30; Senescence in eucalypt species 30; Verification 30; Figs 31<br />

3

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

4<br />

4.4.2 Ground-truthing 34<br />

4.4.3 Incorporation into GIS databases 34<br />

4.4.4 Plot-based vegetation survey 34<br />

Site selection 34; Survey methods 34<br />

4.5 Limitations 35<br />

4.6 Results <strong>and</strong> discussion 35<br />

4.6.1 Representation of vegetation mapping units 35<br />

4.6.2 Distribution of vegetated l<strong>and</strong> 39<br />

4.6.3 Abundance <strong>and</strong> distribution of Camphor Laurel 39<br />

4.6.4 Abundance <strong>and</strong> distribution of old growth eucalypt forest 40<br />

4.6.5 Figs 41<br />

4.6.6 Other vegetation attributes 41<br />

4.7 Description of the vegetation units 41<br />

4.7.1 Rainforest (minimal Camphor Laurel presence) 41<br />

Rainforest

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

5.3 <strong>Flora</strong> species of conservation significance – definitions 62<br />

5.4 Methods 65<br />

5.5 Results <strong>and</strong> discussion 67<br />

5.5.1 Threatened <strong>and</strong> ROTAP species 67<br />

5.5.2 Regionally significant species 67<br />

5.5.3 Reservation adequacy 68<br />

5.5.4 Threats 72<br />

5.5.5 Conclusion 72<br />

6 <strong>Fauna</strong> 73<br />

6.1 Introduction 73<br />

6.1.1 Rainforest <strong>and</strong> wet sclerophyll forest species 73<br />

6.1.2 Dry sclerophyll forest species 73<br />

6.1.3 Swamp sclerophyll forest, woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> coastal scrub species 74<br />

6.1.4 Freshwater species 74<br />

6.1.5 Ephemeral habitat species 74<br />

6.1.6 Saltmarsh, mangrove, estuaries <strong>and</strong> marine shore species 74<br />

6.1.7 Ecological guilds 74<br />

6.1.8 Migration 75<br />

6.2 Methods 75<br />

6.2.1 Collection <strong>and</strong> verification of existing information 75<br />

6.2.2 Field surveys 76<br />

6.3 Results 77<br />

6.3.1 Vertebrate species occurring in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 77<br />

6.3.2 <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> Threatened <strong>Fauna</strong> Species Database 78<br />

7 Threats <strong>and</strong> amelioration 82<br />

7.1 Vegetation clearing 82<br />

7.2 Vegetation connectivity <strong>and</strong> fragmentation 83<br />

7.3 Environmental weeds 84<br />

7.4 Fire 86<br />

7.5 Grazing 88<br />

7.6 Predation by introduced animals 88<br />

7.7 Development 89<br />

8 Ecological assessment 90<br />

8.1 Introduction 90<br />

8.2 Methods 90<br />

8.3 Results <strong>and</strong> discussion 90<br />

9 References 93<br />

5

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

List of appendices<br />

Appendix 1 Soil l<strong>and</strong>scape mapping units, with definitions <strong>and</strong> areas 101<br />

Appendix 2 Plot-based vegetation survey – survey data form 103<br />

Appendix 3 Plot-based vegetation survey – computer database record form 105<br />

Appendix 4 Plot-based vegetation survey – summary of site data 106<br />

Appendix 5 List of plant species referred to in the <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> or in the database 112<br />

Appendix 6 Questionnaire sent to public after media advertisement of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> 130<br />

Appendix 7 Threatened flora species profiles <strong>and</strong> maps showing locations of records within <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 133<br />

Appendix 8 References to other sources of information used to compile the <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> Threatened<br />

<strong>Fauna</strong> Database 194<br />

Appendix 9 A call survey of bats of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong>, NSW 197<br />

Appendix 10 Terrestrial vertebrate species recorded in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 205<br />

Appendix 11 Examples of profiles of Threatened fauna species recorded in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 213<br />

Appendix 12 List of plant species which are known or potential environmental weeds in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 228<br />

Appendix 13 Notes on ecological significance of the l<strong>and</strong> units delineated by ecological assessment 230<br />

6<br />

List of tables<br />

Table 4.1 Vegetation mapping in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> prior to current study 27<br />

Table 4.2 Data sources used to complement the plot-based vegetation survey 35<br />

Table 4.3 Areal extent of vegetation mapping units (including plantations <strong>and</strong> unassessed l<strong>and</strong>s) 36<br />

Table 4.4 Areal extent of vegetation associations (excluding plantations <strong>and</strong> unassessed l<strong>and</strong>s) 37<br />

Table 4.5 Areal occurrence of vegetation mapping units <strong>and</strong> associations by geology/soil type 38<br />

Table 4.6 Old growth eucalypt forest – % of eucalypt crowns showing senescence 40<br />

Table 4.7 Conservation status of the vegetation associations 57<br />

Table 5.1 Definitions – TSC Act status (Threatened Species Conservation Act, 1995) 63<br />

Table 5.2 Definitions – ROTAP status (Rare or Threatened Australian Plants after Briggs <strong>and</strong> Leigh<br />

(1996) 63<br />

Table 5.3 Definitions – regionally significant species after Sheringham <strong>and</strong> Westaway (1995) 64<br />

Table 5.4 Example page from <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> Threatened <strong>Flora</strong> Database 66<br />

Table 5.5 Summary of records of Rare or Threatened flora species 67<br />

Table 5.6 Summary of characteristics of Threatened flora species of the <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 69<br />

Table 5.7 Summary of records of TSC Act scheduled flora species 71<br />

Table 6.1 Threatened fauna species recorded in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>and</strong> analysis of records from the <strong>Byron</strong><br />

<strong>Shire</strong> Threatened fauna database 79<br />

Table 6.2 Example of Threatened vertebrate database used to produce maps of Threatened vertebrate<br />

fauna distribution in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> 81<br />

Table 8.1 Summary of ecological assessment 92

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

List of maps (located between pages 16 <strong>and</strong> 17)<br />

Map 1<br />

Map 2<br />

Map 3<br />

Map 4<br />

Map 5<br />

Map 6<br />

Map 7<br />

Location of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> study area<br />

Soil l<strong>and</strong>scapes of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong><br />

Vegetation of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong><br />

Distribution of Camphor Laurel in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong><br />

Old growth eucalypt forest<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> ecological assessment – areas of high ecological significance<br />

Locations of native fig trees in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong><br />

List of figures<br />

Figure 4.1 Aerial photo with overlay marked with polygon boundaries <strong>and</strong> vegetation classification codes 31<br />

Figure 4.2 Example of aerial photo overlay 32<br />

Figure 4.3 Aerial Photographic Interpretation (API) pathway 33<br />

7

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

8<br />

List of photographs (located between pages 72 <strong>and</strong> 73)<br />

Photo 1 Subtropical rainforest, Wanganui Gorge. Photo D. Milledge i<br />

Photo 2 Brush Box forest, Broken Head. Photo A. McKinley i<br />

Photo 3 Scribbly Gum forest, Taylors Lake. Photo A. McKinley ii<br />

Photo 4 Blackbutt forest, west of Taylors Lake. Photo A. McKinley ii<br />

Photo 5 Clay heath, Patersons Hill. Nominated as an Endangered Ecological Community (TSC Act,<br />

1995). Photo P. Hamilton iii<br />

Photo 6 Coastal mosaic, Cibum Margil Swamp, including (foreground to back) clay heath, Paperbark<br />

forest, sedgel<strong>and</strong>, Wallum Banksia heathl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Horse-tail She-oak. Photo P. Hamilton iii<br />

Photo 7 Paperbark forest, north Ocean Shores. Photo D. Milledge iv<br />

Photo 8 Camphor Laurel-dominated forest (yellow-green foliage), Wilsons Creek. Photo B. Stewart<br />

(inset) Camphor Laurel foliage <strong>and</strong> fruit. Photo H. Nicholson iv<br />

Photo 9 Blackwood regrowth with lantana understorey, Upper Wilsons Creek. Photo B. Stewart v<br />

Photo 10 Sedgel<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> mangrove forest, Marshalls Creek. Photo D. Milledge v<br />

Photo 11 Ball Nut Floydia praealta, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo H. Nicholson vi<br />

Photo 12 Spiny Gardenia R<strong>and</strong>ia moorei, Endangered (TSC Act, 1995). Photo H. Nicholson vi<br />

Photo 13 Durobby Syzygium moorei, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo D. Milledge vi<br />

Photo 14 Isoglossa Isoglossa eranthemoides, Endangered (TSC Act, 1995). Photo H. Nicholson vii<br />

Photo 15 Red Boppel Nut Hicksbeachia pinnatifolia, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo H. Nicholson vii<br />

Photo 16 Smooth Davidsonia Davidsonia sp. A, Endangered (TSC Act, 1995). Photo H. Nicholson vii<br />

Photo 17 Wallum Tree Frog Litoria olongburensis, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo D. Milledge viii<br />

Photo 18 Loveridge’s Frog Philoria loveridgei, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo D. Milledge viii<br />

Photo 19 Blue Speckled Forest Skink Eulamprus murrayi, rainforest skink. Photo D. Milledge ix<br />

Photo 20 Southern Forest Dragon Hypsilurus spinopes. Photo H. Bower ix<br />

Photo 21 Stephen’s B<strong>and</strong>ed Snake Hoplocephalus stephensii, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo P.<br />

German<br />

x<br />

Photo 22 Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus, protected by international treaties for migratory birds. Photo<br />

D. Milledge x<br />

Photo 23 Rose-crowned Fruit-dove Ptilinopus regina, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo G. Threlfo xi<br />

Photo 24 Albert’s Lyrebird Menura alberti, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo G. Threlfo xi<br />

Photo 25 Wompoo Fruit-dove Ptilinopus magnificus, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo G. Threlfo xii<br />

Photo 26 Marbled Frogmouth Podargus ocellatus, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo D. Milledge xii<br />

Photo 27 Golden-tipped Bat Kerivoula papuensis, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo P. German xii<br />

Photo 28 Common Planigale Planigale maculatus, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo D. Milledge xiii<br />

Photo 29 Koala Phascolarctos cinereus, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo H. Bower xiii<br />

Photo 30 Eastern Tube-nosed Bat Nyctimene robinsoni, Vulnerable (TSC Act, 1995). Photo P. German xiii<br />

Photo 31 Large-leaved Privet Ligustrum lucidum, environmental weed. Photo H. Nicholson xiv<br />

Photo 32 Mickey Mouse Plant Ochna serrulata, environmental weed. Photo H. Nicholson xiv<br />

Photo 33 Ground Asparagus Protasparagus aethiopicus <strong>and</strong> Fish-bone Fern Nephrolepis cordifolia,<br />

environmental weeds. Photo A. McKinley. xv<br />

Photo 34 Madeira Vine Anredera cordifolia, environmental weed, in flower, vine smothering a rainforest<br />

tree <strong>and</strong> (inset) aerial tubers. Photo H. Nicholson. xv<br />

Photo 35 Booyong <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> Reserve, internally fragmented rainforest remnant. Photo D.<br />

Milledge<br />

xvi<br />

Photo 36 Riparian vegetation fringing Mullumbimby Creek, with Mt Chincogan in background. Photo B.<br />

Stewart<br />

xvi

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

The project team<br />

The project was managed by L<strong>and</strong>mark Ecological Services Pty Ltd (Annette McKinley, David Milledge,<br />

Hugh Nicholson, Nan Nicholson <strong>and</strong> Barbara Stewart).<br />

The flora component of the study (including vegetation surveys, Threatened species searches,<br />

interpretation of vegetation mapping <strong>and</strong> description of vegetation units, Threatened flora profiles<br />

<strong>and</strong> database, ecological assessment <strong>and</strong> flora report) was undertaken by Barbara Stewart <strong>and</strong> Annette<br />

McKinley. The fauna component of the study (including fauna survey, fauna species profiles <strong>and</strong> fauna<br />

report) was managed by David Milledge. Harry Parnaby carried out bat surveys. Alistair Stewart <strong>and</strong><br />

Tom Milledge assisted in the office <strong>and</strong> in the field.<br />

Peter Hall, Sunniva Boulton <strong>and</strong> Mark Kingston from Ecograph managed the GIS <strong>and</strong> data management<br />

component of the study including design of the GIS <strong>and</strong> vegetation survey databases, digitising, map<br />

production <strong>and</strong> reporting for Section 3.<br />

Marg East <strong>and</strong> Chris Carson from Terra Focus Pty Ltd undertook the aerial photo interpretation <strong>and</strong> groundtruthing<br />

<strong>and</strong> prepared Sections 4.4.1-4.4.3 of this report.<br />

Sue Walker co-ordinated the project <strong>and</strong> Hank Bower managed the final report production.<br />

9

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Many people contributed to this study, including an overwhelming majority of enthusiastic l<strong>and</strong>holders who<br />

allowed access to their properties <strong>and</strong> provided information on local fauna <strong>and</strong> flora.<br />

Thanks are also due to the people who assisted with the project by providing information on Threatened<br />

flora <strong>and</strong> fauna species, including Andrew Benwell, Glenn Hoye, Andrew Murray, Brad McDonald, Charlie<br />

Ohle, Dave Stewart, Di Mackey, Glenn Holmes, Hank Bower, Harry Parnaby, Jack Willows, Jan Oliver,<br />

Jenny Holmes, Justin Miller, Mort Kaveney, Mark Fitzgerald, Rob Doolan, Rob Kooyman, Bob Oehlman,<br />

Peter Parker, S<strong>and</strong>y Gilmore, Stan Scanlon, Bob Gray, Liz Gray, Gary Opit, Steve Phillips, Sue Bower, Val<br />

Scanlon, Merv Whicker <strong>and</strong> other residents of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> who responded to the Threatened Species<br />

Questionnaire. Andrew Murray, Andrew Benwell, S<strong>and</strong>y Gilmore <strong>and</strong> Peter Parker provided information<br />

on previously mapped areas of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> (in particular Broken Head, Jones Rd, Cape <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>and</strong> Ewingsdale).<br />

Andrew Benwell, Andrew Murray, Hank Bower <strong>and</strong> Sue Bower contributed site data.<br />

10

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

Mayor’s foreword<br />

The <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> was initiated in response to a strong community desire to preserve flora<br />

<strong>and</strong> fauna through the promotion of ecologically sustainable l<strong>and</strong> use planning <strong>and</strong> decision making. The<br />

<strong>Study</strong> provides detailed ecological information, including the occurrence <strong>and</strong> distribution of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s<br />

vegetation associations <strong>and</strong> flora <strong>and</strong> fauna species (with particular regard to Threatened <strong>and</strong> significant<br />

species). The <strong>Study</strong> relied on the involvement of the community, environmental consultants <strong>and</strong> government<br />

agencies. L<strong>and</strong>owners were particularly helpful in providing access to their properties for the collection <strong>and</strong><br />

verification of field <strong>and</strong> mapping data. I am grateful to everyone who was involved in its preparation.<br />

The <strong>Study</strong> shows that much of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s vegetation has been heavily impacted by rural <strong>and</strong> urban development<br />

over the past 100 years. This has resulted in a matrix of fragmented patches of remnant vegetation <strong>and</strong> the<br />

establishment of large areas of regrowth forests, many of which are dominated by environmental weeds,<br />

particularly the exotic tree Camphor Laurel. Despite this the <strong>Shire</strong> remains an area of extremely high<br />

biodiversity, with amongst the highest number of Threatened flora <strong>and</strong> fauna species in NSW. The sort of<br />

knowledge gained through this <strong>Study</strong> places a great obligation on the <strong>Council</strong>, l<strong>and</strong>holders <strong>and</strong> the community<br />

to protect remaining habitats outside of conservation reserves <strong>and</strong> develop appropriate strategies <strong>and</strong> priorities<br />

for the restoration <strong>and</strong> enhancement of degraded l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> species habitats.<br />

If the ‘green image’ of the <strong>Shire</strong> is to survive actions are needed to incorporate specific ecological requirements<br />

for species, populations <strong>and</strong> ecological communities into l<strong>and</strong> management <strong>and</strong> development processes.<br />

The challenge ahead is to protect, restore <strong>and</strong> manage our biodiversity in a manner that enhances the social,<br />

economic <strong>and</strong> ecological attributes of our community <strong>and</strong> the lifestyles it supports. The <strong>Study</strong> provides a<br />

benchmark by which future generations can measure how well today’s generation met this challenge.<br />

Tom Wilson,<br />

Mayor<br />

February 2000<br />

11

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

Director’s comments<br />

The <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> provides the foundation for preparing the <strong>Byron</strong> Biodiversity Conservation<br />

Strategy, the Wildlife Corridor <strong>and</strong> Environmental Repair <strong>and</strong> Enhancement Local Environmental Plan<br />

Amendment, a <strong>Shire</strong>-wide Vegetation Plan <strong>and</strong> a <strong>Shire</strong>-wide Koala Management Plan. I also hope this <strong>Study</strong><br />

will prove useful for l<strong>and</strong>holders, community groups, private consultants, students, government agencies<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Council</strong> staff in assessing the conservation significance of areas <strong>and</strong> in the implementation of restoration<br />

actions throughout the <strong>Shire</strong>. The <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> is your <strong>Study</strong> so please use it to help the community<br />

develop its pathway to an ecologically sustainable future.<br />

David Kanaley,<br />

Director<br />

Environmental Planning Services<br />

12

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

Executive summary<br />

STUDY OUTCOMES<br />

4 Major outcomes from the study include:<br />

• Vegetation mapping<br />

• Senescent old growth eucalypt mapping<br />

• <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> fauna species records<br />

• Camphor Laurel mapping<br />

• Location of native fig trees<br />

• Vegetation communities <strong>and</strong> associations descriptions<br />

• Area of each vegetation association<br />

• Level of verification/field assessment<br />

• Percentage <strong>and</strong> description of Camphor Laurel<br />

• Percentage <strong>and</strong> description of weed <strong>and</strong> pasture<br />

• GIS databases<br />

• Field Survey Database<br />

• Rare or Threatened <strong>Flora</strong> Species Database<br />

• Threatened <strong>Fauna</strong> Species Database<br />

The <strong>Study</strong> provides excellent information for <strong>Shire</strong>-wide planning. However, at the property level further<br />

field validation by expert practitioners is required to validate vegetation mapping <strong>and</strong> to undertake targeted<br />

flora <strong>and</strong> fauna surveys. Information from such assessments should be provided for inclusion into <strong>Council</strong>’s<br />

database. Minimum st<strong>and</strong>ards for survey methodology will be set by <strong>Council</strong> to ensure data is acceptable for<br />

inclusion into <strong>Council</strong>’s database.<br />

OVERALL<br />

4 <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> is an area of extremely high biodiversity (ecosystems, species <strong>and</strong> genetic diversity).<br />

4 Many plant <strong>and</strong> animal species with origins in the tropics <strong>and</strong> temperate zones occur in the <strong>Shire</strong>.<br />

That is, many species are at their southern limit of distribution (tropical species) while others are<br />

at their northern limit (temperate species). Additionally, the <strong>Shire</strong> provides important relictual<br />

habitat for subtropical rainforest species.<br />

4 Several primitive rainforest plant species which are related to ancient families are found here.<br />

4 The <strong>Shire</strong> has one of the highest numbers of Threatened flora <strong>and</strong> fauna species in NSW.<br />

VEGETATION<br />

4 17,720 ha, representing 34% of the <strong>Shire</strong> study area, is vegetated with native or introduced trees<br />

<strong>and</strong> shrubs <strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong> plants. The native vegetation has been extensively depleted, fragmented,<br />

largely disturbed <strong>and</strong> degraded <strong>and</strong> in some localities is dominated by exotic species.<br />

13

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

4 Some types of native vegetation have been more heavily impacted than others. Vegetation growing<br />

on prime agricultural l<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> favoured for settlement <strong>and</strong> coastal development, has been<br />

targeted for development to a greater extent than vegetation on soils of low fertility, on steep slopes<br />

<strong>and</strong> in the less accessible hinterl<strong>and</strong>. As a result, vegetation types such as lowl<strong>and</strong> rainforest are<br />

now scarce in the <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>and</strong> in the Northern Rivers region when compared to their previous<br />

distribution.<br />

4 The remaining native vegetation is distributed unevenly, with the hinterl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the less fertile<br />

coastal areas containing the most extensive cover <strong>and</strong> the coastal plains <strong>and</strong> ridges being<br />

predominantly cleared.<br />

4 The coastal plain is severely denuded of tree cover, <strong>and</strong> the remaining native vegetation is present<br />

as small fragments.<br />

4 The most abundant vegetation association involves the introduced tree, Camphor Laurel Cinnamomum<br />

camphora, which occupies more than one quarter of the vegetated area of the <strong>Shire</strong>. Blackbutt<br />

Eucalyptus pilularis <strong>and</strong> rainforest are the next most abundant, while only tiny amounts of other<br />

vegetation types such as Pink Bloodwood Corymbia intermedia, Scribbly Gum Eucalyptus signata-Red<br />

Bloodwood Corymbia gummifera <strong>and</strong> Black She-oak Allocasuarina littoralis occur.<br />

4 Camphor Laurel dominated forests now cover 4,696 ha. Of these 1,532 ha are forest with Camphor<br />

Laurel comprising more than 81% of the canopy cover. Camphor Laurel was mainly recorded on<br />

basalt derived soils.<br />

4 Big Scrub rainforest remnants are located in small fragments on the <strong>Shire</strong>’s basalt plateau.<br />

4 Rainforest provides habitat for a high number of Threatened plant species.<br />

4 A number of the vegetation associations are of high conservation significance. Most exist as small<br />

percentages of their estimated pre-1750 areas in north-east NSW. Many are poorly reserved,<br />

e.g. Forest Red Gum Eucalyptus tereticornis, Scribbly Gum, Swamp Oak Casuarina glauca <strong>and</strong> Black<br />

She-oak.<br />

4 Most of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s eucalypt-dominated forest has little or no old growth component, reflecting a<br />

history of logging, clearing or inappropriate fire regimes. Old growth eucalypt is important habitat<br />

for Threatened fauna species.<br />

4 Only 510 ha (1% of the study area) has a high proportion of old (senescing) eucalypt trees <strong>and</strong><br />

these areas are located only in the forested hinterl<strong>and</strong> of the <strong>Shire</strong>. No areas with a high proportion<br />

of old eucalypts were found on the coastal plains. A further 772 ha (1.5% of study area) has an<br />

intermediate proportion of old trees <strong>and</strong> these areas are also found in the forested hinterl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

However, importantly, small coastal areas of eucalypt old growth are found at North Ocean Shores,<br />

near the Brunswick River west of Mullumbimby, Tyagarah, Skinners Shoot, south of Suffolk Park<br />

<strong>and</strong> south of the Broken Head Beach Road. A further 2,547 ha has a low proportion of old (senescing)<br />

eucalypt trees.<br />

FLORA<br />

4 Important timber <strong>and</strong> bush food species are native to the <strong>Shire</strong>, as well as many other species with<br />

actual <strong>and</strong> potential economic value.<br />

4 38 plant species recognised as Threatened (listed as Endangered or Vulnerable under the TSC Act,<br />

1995) have been recorded in the <strong>Shire</strong>.<br />

4 With two exceptions, all the <strong>Shire</strong>’s Threatened plant species are considered to be inadequately<br />

reserved in formal conservation reserves. Adequate reservation for many of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s Threatened<br />

species is often not possible, due to the extensive clearing of their habitat on the coastal lowl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

14

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

4 Some Threatened plant species are actually locally common in some areas in the <strong>Shire</strong>; however,<br />

their distribution outside the <strong>Shire</strong> is extremely limited. That is, the <strong>Shire</strong> provides the core habitat<br />

for these plants <strong>and</strong> it is essential that their populations are maintained in the <strong>Shire</strong>.<br />

4 Environmental weeds are a major threat to Threatened plant species.<br />

4 Some of the listed Threatened plant species are ‘ecologically extinct’; meaning that they have<br />

regeneration failure <strong>and</strong> an inability to disperse seeds effectively. This will lead to the decline of the<br />

species as existing plants senesce. Smooth Davidsonia Davidsonia sp. A <strong>and</strong> Hairy Qu<strong>and</strong>ong Elaeocarpus<br />

williamsianus are species that never or rarely reproduce by seed <strong>and</strong> they rely on root suckers. The<br />

future survival of such species is in jeopardy, as they cannot disperse to new sites. Habitat<br />

rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> active management is required to conserve these species effectively in the long term.<br />

FAUNA<br />

4 The <strong>Shire</strong> is part of a region which is one of the richest <strong>and</strong> most diverse in Australia. Habitats are<br />

diverse <strong>and</strong> there is a particularly wide variety of niches for animals. The ranges of many tropical<br />

<strong>and</strong> temperate species overlap here.<br />

4 420 terrestrial vertebrate species (30 amphibians, 45 reptiles, 283 birds <strong>and</strong> 62 mammals) are<br />

known from the <strong>Shire</strong>. One amphibian, five birds <strong>and</strong> six mammals are naturalised exotic species.<br />

70 species or 17% are regarded as Threatened (listed as Endangered or Vulnerable under the TSC<br />

Act, 1995).<br />

4 Targeted surveys were carried out for poorly known Threatened species (Loveridge’s Frog Philoria<br />

loveridgei, Stephen’s B<strong>and</strong>ed Snake Holocephalus stephensii, Square-tailed Kite Lophoictinia isura,<br />

Comb-crested Jacana Irediparra gallinacea, Powerful Owl Ninox strenua, Masked Owl Tyto<br />

novaeholl<strong>and</strong>iae, Marbled Frogmouth Podargus ocellatus, Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, Barred<br />

Cuckoo-shrike Coracina lineata).<br />

4 Bats are widely distributed in the <strong>Shire</strong>. Significant bat assemblages are present <strong>and</strong> Vulnerable<br />

species (e.g. Eastern Tube-nosed Bat Nyctimene robinsoni, Yellow-bellied Sheathtail Bat Saccolaimus<br />

flaviventris, Golden-tipped Bat Kerivoula papuensis, Large-eared Pied Bat Chalinolobus dwyeri, Greater<br />

Broad-nosed Bat Scoteanax rueppellii) were detected during the surveys.<br />

4 Surveys were carried out for microchiropteran bats, using ultrasonic detection methods, <strong>and</strong><br />

targeting nine Vulnerable species at 52 sites.<br />

4 Distribution maps were generated for all 70 Threatened fauna species from the database <strong>and</strong> are<br />

stored on <strong>Council</strong>’s GIS.<br />

HABITAT BLOCKS<br />

4 Core areas of native vegetation with major importance as fauna habitat blocks are located mainly in<br />

the north <strong>and</strong> north-west of the <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>and</strong> along the coastal strip. These areas should be given<br />

priority for revegetation <strong>and</strong> rehabilitation.<br />

WILDLIFE CORRIDORS<br />

4 A severance of the hinterl<strong>and</strong> forests from the coastal vegetation systems has resulted from large<br />

scale clearing of the coastal plain <strong>and</strong> the basalt plateau. A tenuous connection remains in the<br />

Marshalls Ridge area in the north of the <strong>Shire</strong> linking Billinudgel Nature Reserve at North Ocean<br />

Shores to Inner Pocket Nature Reserve <strong>and</strong> through Tweed <strong>Shire</strong> to Mt Warning National Park.<br />

Other connections consist of a series of ‘isl<strong>and</strong>s’ of vegetation.<br />

4 A narrow coastal corridor exists but it is interrupted by settlements <strong>and</strong> clearings.<br />

15

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

4 Corridors do not necessarily consist of continuous vegetation as some animals (particularly the<br />

more mobile species) are capable of ‘isl<strong>and</strong> hopping’ between patches of vegetation <strong>and</strong> isolated<br />

trees. It should be a priority to establish links between vegetation patches within a functioning<br />

wildlife corridor.<br />

4 Consolidation <strong>and</strong> expansion of habitat patches may sometimes be a better use of resources than<br />

the creation of a corridor. However, this needs to be considered on a site by site basis <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

context needs to be taken into consideration.<br />

WEEDS AND REHABILITATION<br />

4 Environmental weeds seriously threaten the <strong>Shire</strong>’s biodiversity. A large number of environmental<br />

weeds are known in the <strong>Shire</strong>. To guide management, further ground-based surveys are required<br />

to determine their distribution <strong>and</strong> abundance.<br />

4 Education of the community <strong>and</strong> the horticultural industry is needed to prevent planting of<br />

ecologically damaging species, <strong>and</strong> to prevent dumping of garden refuse.<br />

4 Some weed species, which are problematic in the region, are absent or in small localised infestations<br />

within the <strong>Shire</strong>. An opportunity exists to eliminate or contain them.<br />

4 Integrated rehabilitation techniques that aim to restore important ecosystem functions are<br />

recommended as they will improve an ecosystem’s ability to naturally regenerate <strong>and</strong> promote<br />

conditions that will disadvantage the establishment of exotic species. Weed removal strategies that<br />

target single species are only recommended where early intervention of a serious weed will prevent<br />

the spread or establishment of a more serious infestation. In these instances the removal of seed<br />

sources (propagules) is a primary aim.<br />

4 The value of some weeds for fauna food resources <strong>and</strong> shelter must be considered in any strategy.<br />

THE FUTURE<br />

4 Despite some areas of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s vegetation being in a degraded condition, they still possess high<br />

conservation values for fauna habitat attributes <strong>and</strong> the presence of Rare or Threatened plant<br />

species, <strong>and</strong> excellent potential for consolidation <strong>and</strong> rehabilitation.<br />

4 As native vegetation cover is already severely depleted in the <strong>Shire</strong>, it is now essential to retain <strong>and</strong><br />

enhance the remaining native vegetation <strong>and</strong> revegetate to the extent that other l<strong>and</strong> uses <strong>and</strong><br />

available resources will allow. Measures required include:<br />

16<br />

• protection of remaining vegetation<br />

• rehabilitation of degraded vegetation<br />

• enrichment of species-poor regrowth<br />

• natural regeneration, with management where necessary<br />

• direct seeding<br />

• planting<br />

4 There is a strong need to protect <strong>and</strong> manage the rainforest remnants <strong>and</strong> small forested areas with<br />

old trees, particularly those remnant areas on the coastal plain.<br />

4 Protection <strong>and</strong> enhancement of vegetation, flora <strong>and</strong> fauna on private l<strong>and</strong> is a special responsibility<br />

for l<strong>and</strong>owners <strong>and</strong> managers in this biologically important region. Conservation agreements <strong>and</strong><br />

co-operative local strategies, coupled with liaison with NSW NPWS where management of<br />

Threatened species <strong>and</strong> their habitats is involved, are suggested.<br />

4 Existing GIS <strong>and</strong> databases are in a form which can readily be built on to assist management on<br />

<strong>Shire</strong>-wide or local scales.

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

1<br />

Introduction<br />

1.1 BACKGROUND<br />

L<strong>and</strong>mark Ecological Services Pty Ltd were engaged by <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong> to conduct a study of the flora<br />

<strong>and</strong> fauna of the <strong>Shire</strong>. Terrafocus Pty Ltd was sub-contracted to undertake Aerial Photo Interpretation <strong>and</strong><br />

Ecograph Pty Ltd was sub-contracted to design <strong>and</strong> construct a field survey database <strong>and</strong> GIS databases,<br />

digitise mapping <strong>and</strong> undertake tasks associated with map layout <strong>and</strong> production.<br />

The aim of the study was:<br />

to provide <strong>Council</strong> with information on the distribution of plant communities <strong>and</strong> associations, <strong>and</strong><br />

Threatened <strong>and</strong> significant flora <strong>and</strong> fauna species throughout the <strong>Shire</strong>.<br />

This information is important to enable <strong>Council</strong> to be appropriately advised in its decision making <strong>and</strong> to<br />

ensure it achieves its goal of ecologically sustainable development, particularly the principle of the conservation<br />

of biological diversity.<br />

The <strong>Study</strong> Brief states:<br />

The <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Study</strong> entails the systematic collation of existing records, vegetation mapping<br />

<strong>and</strong> flora <strong>and</strong> fauna surveys. The <strong>Study</strong> places an emphasis on Threatened species of flora <strong>and</strong> fauna<br />

<strong>and</strong> significant plant associations. The results will be collected in a format suitable for analysis in<br />

<strong>Council</strong>’s Geographical Information System.<br />

The outcomes of the <strong>Study</strong> are intended to provide comprehensive information on species<br />

distributions <strong>and</strong> biodiversity management issues. This information is essential to achieve ecological<br />

sustainability, a cornerstone of which is biodiversity conservation <strong>and</strong> management. Ecologically<br />

sustainable use of natural resources can only be achieved by incorporating detailed biological resource<br />

information <strong>and</strong> sound ecological principles into l<strong>and</strong> use planning.<br />

The study was carried out by L<strong>and</strong>mark Ecological Services Pty Ltd, Ecograph <strong>and</strong> Terrafocus Pty Ltd over<br />

two years from January 1997 to December <strong>1999</strong>. Data collection <strong>and</strong> compilation essentially ceased in<br />

August 1998, though some modifications <strong>and</strong> additions were made during the draft preparation, public<br />

exhibition period <strong>and</strong> finalisation of the report (see also Section 1.3).<br />

Subsequent to public exhibition <strong>Council</strong> in collaboration with L<strong>and</strong>mark Ecological Services Pty Ltd made<br />

further amendments to the <strong>Study</strong> in response to the public submissions. <strong>Council</strong> made these amendments<br />

in recognition of the planning process currently underway on the proposed Wildlife Corridor <strong>and</strong><br />

Environmental Repair <strong>and</strong> Enhancement Zone <strong>and</strong> the proposed Biodiversity Conservation Strategy.<br />

1.2 STUDY AREA<br />

The study area defined for the purposes of this document includes all private l<strong>and</strong>, Crown l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Council</strong>owned<br />

l<strong>and</strong> within <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> (as at August 1998). The study area occupied 51,453 ha of the <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong>’s<br />

total area of 56, 642 ha. Information about the flora <strong>and</strong> fauna of l<strong>and</strong>s outside the study area (State Forests,<br />

17

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

National Parks, Nature Reserves <strong>and</strong> other reserves) was usually held by the relevant l<strong>and</strong> managers, <strong>and</strong><br />

vegetation mapping for State Forests <strong>and</strong> the National Parks estate was in progress during the study period.<br />

Therefore, these public l<strong>and</strong>s were not included in the study area. However, these additional l<strong>and</strong>s provide<br />

context for the study of biodiversity elsewhere in the <strong>Shire</strong>, <strong>and</strong> inevitably required consideration. Generally,<br />

public l<strong>and</strong>s were considered during the study but were usually treated differently from the study area<br />

(described in each relevant section).<br />

At the commencement of the study, terrestrial vascular flora <strong>and</strong> terrestrial vertebrate fauna were the only<br />

groups of species occurring within <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> that were represented on the Schedules of the TSC Act,<br />

1995. Consultation with <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>Council</strong> resulted in a decision to restrict the study to these groups.<br />

1.3 ON-GOING PROCESSES<br />

Changes to l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong> assessment of conservation status are on-going <strong>and</strong> have taken place during the<br />

study period. Major changes to l<strong>and</strong> tenure, involving the transfer of the bulk of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s State Forests <strong>and</strong><br />

Crown L<strong>and</strong> to the National Parks estate took place at the end of the study period. These changes will alter<br />

the areas of some vegetation mapping units, the reservation status of some species, vegetation communities<br />

<strong>and</strong> associations, <strong>and</strong> will decrease some threats to some species.<br />

Schedules of the TSC Act, 1995 have been modified <strong>and</strong> extended during the study period. The status of<br />

two Threatened flora species that occur in the <strong>Shire</strong> has changed whilst an invertebrate fauna species (the<br />

l<strong>and</strong> snail Thersites mitchelliae, known from the Cumbebin Swamp area) has been listed as Endangered. Two<br />

new Key Threatening Processes have been declared, being the Invasion of Native Plant Communities by<br />

Bitou Bush Chrysanthemoides monilifera <strong>and</strong> Predation by the Plague Minnow (or Mosquito Fish) Gambusia<br />

holbrooki. In addition Lowl<strong>and</strong> Rainforest on Floodplain has been declared an Endangered Ecological<br />

Community <strong>and</strong> aquatic vertebrate species have been listed as Threatened under the Fisheries Management<br />

Act, 1994.<br />

These changes have been incompletely incorporated into this report <strong>and</strong> associated databases <strong>and</strong> maps, as<br />

noted in the relevant sections.<br />

18

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

2<br />

The environment of<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong><br />

2.1 LOCATION AND PHYSIOGRAPHY<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> is located in the far north-eastern corner of NSW between Tweed <strong>Shire</strong> in the north, City of<br />

Lismore to the west <strong>and</strong> Ballina <strong>Shire</strong> to the south (Map 1). The north-eastern corner of the <strong>Shire</strong> is located<br />

approximately 2 km south of Wooyung <strong>and</strong> the north-western corner extends into the upper catchment of<br />

the Brunswick River. The western boundary runs through Mount Jerusalem <strong>and</strong> Nightcap National Parks,<br />

follows Coopers Creek <strong>and</strong> then continues south to, but not including the village of Clunes, <strong>and</strong> then to the<br />

Wilson River. The southern boundary follows the Wilson River upstream to Skinners Creek, to the headwaters<br />

of Skinners Creek across to Piccadilly Hill, Newrybar, Broken Head <strong>and</strong> the coast.<br />

The <strong>Shire</strong> comprises five l<strong>and</strong> form units - coastline, coastal lowl<strong>and</strong>s, coastal ridges, the undulating volcanic<br />

plateau <strong>and</strong> mountain ridges <strong>and</strong> valleys (Planning Workshop 1983).<br />

2.1.1 Coastline<br />

The coastline north of Cape <strong>Byron</strong> has been formed by the dominant south-easterly swell conditions, which<br />

refract around Cape <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>and</strong> Julian Rocks producing a hooked region in the south which smooths out to<br />

the north (Planning Workshop 1983).<br />

Between Cape <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>and</strong> Brunswick Heads lies an extensive system of shoreline parallel ridges spaced from<br />

150 metres to 180 metres apart. These were formed during a rise in sea level when barrier-building s<strong>and</strong>s<br />

were moved onshore (Planning Workshop 1983). To the north of Brunswick Heads, the ridge system<br />

becomes narrow <strong>and</strong> discontinuous, generally varying in height from 3 metres to 9 metres above sea level.<br />

An eroded dune scarp 2 metres to 6 metres high backs the present-day beach. At Brunswick Heads, a low<br />

but well-developed fore-dune extends 2 kilometres to the south. This dune is the result of localised accretion<br />

behind the breakwater (Planning Workshop 1983).<br />

2.1.2 Coastal plain<br />

The coastal plain is a low-lying area situated between the base of the escarpment, coastal ridges <strong>and</strong> the<br />

coastal dune system. The plain has an upper elevation of 10 to 20 metres <strong>and</strong> slopes varying from 0 - 5%<br />

<strong>and</strong> is comprised of stream alluvium <strong>and</strong> s<strong>and</strong> deposited over time from offshore. The l<strong>and</strong> is low lying with<br />

several areas of surface water, e.g. Cumbebin Swamp <strong>and</strong> Belongil Swamp. An extensive heathl<strong>and</strong> lies north<br />

from the Belongil Swamp to the Brunswick River. This heathl<strong>and</strong>, which is incorporated into Tyagarah<br />

Nature Reserve, grows largely on an extensive hind-dune system, the dunal swales strongly aligned in a<br />

north-south direction parallel to the coastline.<br />

2.1.3 Coastal ridges<br />

Most of the coastal ridges run east-west. These ridges may attain a height of 100 metres inl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> drop to<br />

around 50 metres above sea level as they approach the coastal dune system. They are predominantly higher<br />

in the north of the <strong>Shire</strong>.<br />

19

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

Ridges in the far north of the <strong>Shire</strong> still contain areas of eucalypt <strong>and</strong> Brush Box forests, but the ridges<br />

further south have been largely cleared for dairying <strong>and</strong> grazing.<br />

2.1.4 Undulating volcanic plateau<br />

An undulating volcanic plateau (altitude 100-250 m above sea level) covers the majority of the southwestern<br />

portion of the <strong>Shire</strong>. The plateau has resulted from long term erosion of the massive volcanic lava<br />

flows from Mt Warning. The eastern boundary is sharply defined by the coastal escarpment (Planning<br />

Workshop 1983).<br />

2.1.5 Mountain ranges <strong>and</strong> valleys<br />

Mountains <strong>and</strong> valleys comprise the north-west of the <strong>Shire</strong>. The mountain ranges constitute the easterly<br />

portion of the Nightcap Range, the dominant peaks being Mt Jerusalem (800 m), Mt Boogarem (640 m)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Mt Peak (600 m). Mt Chincogan (307 m) st<strong>and</strong>s isolated, to the north of Mullumbimby.<br />

The <strong>Shire</strong> includes the catchment of the Brunswick River <strong>and</strong> its tributaries (Kings Creek, Mullumbimby<br />

Creek, Yankee Creek, Blindmouth Creek, Lacks Creek, Yelgun Creek) <strong>and</strong> the catchments of the large<br />

coastal creeks, Marshalls Creek, Simpsons Creek, Belongil Creek <strong>and</strong> Tallow Creek. Coopers Creek <strong>and</strong><br />

Wilsons Creek flow out of the <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>and</strong> drain into the Richmond River system.<br />

2.2 CLIMATE, TEMPERATURE, RAINFALL AND SEASONALITY<br />

The <strong>Shire</strong>’s climate is warm subtropical with heavy summer rainfall (January to March) <strong>and</strong> a dry winter<br />

<strong>and</strong> spring. Rainfall is high – a result of mountainous topography close to the coast (Forestry Commission<br />

of NSW 1996). The average annual rainfall tends to decrease from east to west across the <strong>Shire</strong> from 1,868<br />

mm at Cape <strong>Byron</strong>, 1,856 mm at Newrybar, 1,880 mm at Bangalow, 1,773 mm at Mullumbimby, 1,763<br />

mm at Federal <strong>and</strong> 1,429 mm at Dunoon. The Nightcap <strong>and</strong> Koonyum Ranges in the northwestern <strong>and</strong><br />

western parts of the <strong>Shire</strong> experience higher rainfall (Planning Workshop 1983). During the wet season,<br />

heavy mists frequently cover the higher peaks <strong>and</strong> ranges <strong>and</strong> in the warmer summer-autumn months,<br />

tropical cyclones often move down the Queensl<strong>and</strong> coast from the Coral Sea <strong>and</strong> affect <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong>, bringing<br />

flood rains <strong>and</strong> strong winds (Forestry Commission of NSW 1996).<br />

The only weather station that collects systematic temperature readings for <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> is located at Cape<br />

<strong>Byron</strong>. The mean maximum temperature recorded at Cape <strong>Byron</strong> in July is 19.3° Celsius <strong>and</strong> in January<br />

27.5°. The mean minimum temperature recorded at Cape <strong>Byron</strong> in July is 11.5° <strong>and</strong> in January 20.8°.<br />

2.3 LAND TENURE, PROTECTED AREAS<br />

National Parks (NP) (which combine conservation with recreational opportunities) <strong>and</strong> Nature Reserves<br />

(NR) (which are reserved primarily for conservation <strong>and</strong> research) occupied 2,637.9 ha <strong>and</strong> made up 4.7%<br />

of the <strong>Shire</strong> at the commencement of this study. Reserved areas in the hinterl<strong>and</strong> are Nightcap NP (part),<br />

Mt Jerusalem NP <strong>and</strong> Inner Pocket NR. Small rainforest remnant reserves are Snows Gully NR, Andrew<br />

Johnston Big Scrub NR <strong>and</strong> Hayters Hill NR. Coastal reserves are Billinudgel NR (part), Brunswick Heads<br />

NR, Tyagarah NR <strong>and</strong> Broken Head NR. The proclamation of the proposed Arakwal National Park at <strong>Byron</strong><br />

Bay had not been finalised at the time of this study. In addition, a small rainforest reserve at Booyong is<br />

administered by a trust.<br />

Up until November 1998 when the State Government legislated its Regional Forest Agreement, State<br />

Forests (SF) occupied 2,551.7 ha <strong>and</strong> made up 4.5% of the <strong>Shire</strong>. The <strong>Shire</strong>’s State Forests were in the<br />

hinterl<strong>and</strong> at higher altitudes <strong>and</strong> included Whian Whian SF (part), Nullum SF <strong>and</strong> Goonengerry SF. State<br />

Forests are dedicated for timber production but are also managed for conservation <strong>and</strong> recreation, <strong>and</strong><br />

include specific conservation reserves (Minyon Falls <strong>Flora</strong> Reserve in Whian Whian SF <strong>and</strong> Boogarem Falls<br />

<strong>Flora</strong> Reserve in Nullum SF).<br />

20

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

In November 1998 the State Government revoked the State Forests in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> <strong>and</strong> gazetted them as<br />

National Parks. This resulted in part Whian Whian SF (excluding Rummery Park area) being added to<br />

Nightcap NP, Nullum SF being added to Mt Jerusalem NP <strong>and</strong> Goonengerry SF becoming Goonengerry<br />

NP. Further to this in March <strong>1999</strong>, the State Government declared some Crown l<strong>and</strong> as Nature Reserves.<br />

This resulted in Marshalls Creek NR (112 ha), Cumbebin Swamp NR (40 ha), additions to Tyagarah NR<br />

(12 ha) <strong>and</strong> additions to Brunswick Heads NR (115 ha).<br />

The recent additions to National Parks <strong>and</strong> Nature Reserves in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> include approximately 2,830<br />

ha. These additions were made at the conclusion of this study. There is now a need to update the information<br />

on conservation status (Section 4.8). Overall, it has resulted in a doubling of the area protected in National<br />

Parks <strong>and</strong> Nature Reserves, with approximately 10% of the <strong>Shire</strong> being protected for conservation.<br />

Reserved areas are concentrated in the hinterl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> along the coastal strip. The coastal plains <strong>and</strong> basalt<br />

plateau are poorly represented in the reserve system.<br />

2.4 GEOLOGY AND SOILS<br />

Existing geological mapping is coarse in relation to the scale desirable for the purposes of this study. Excellent<br />

soil l<strong>and</strong>scape mapping has been carried out recently (Mor<strong>and</strong> 1994, 1996). The soil l<strong>and</strong>scape units have<br />

been grouped into categories relevant to flora <strong>and</strong> fauna distribution (mainly based on geological parent<br />

material) to produce a geology/soils map (Map 2). Descriptions of the soil l<strong>and</strong>scape mapping units, groupings<br />

used for this study, <strong>and</strong> areal occurrence of each category are appended (Appendix 1).<br />

The oldest or basement rocks of <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> are comprised of Neranleigh-Fernvale metasediments from<br />

the Brisbane Metamorphic Series. These rocks are of palaeozoic age (500-250 million years ago) <strong>and</strong> consist<br />

of siltstones <strong>and</strong> mudstones with s<strong>and</strong>stones <strong>and</strong> conglomerates. The basement metasediments are exposed<br />

in a number of localities along the coast including Cape <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>and</strong> Broken Head, <strong>and</strong> can also be seen at the<br />

base of the coastal escarpment (Planning Workshop 1983).<br />

The basement rocks are overlain in part by mesozoic sediments formed by erosion during the Triassic,<br />

Jurassic <strong>and</strong> Cretaceous periods (210-135 million years ago) (Richmond Valley Naturalists Club 1975).<br />

These sediments consisting of conglomerates, s<strong>and</strong>stones, silt-stones, shale <strong>and</strong> carboniferous shale can be<br />

seen in the cliffs behind <strong>Byron</strong> Hills Estate to the west of Suffolk Park.<br />

The mesozoic sediments are in turn overlain by Mt Warning volcanics. These volcanics consist of a sequence<br />

of lava flows from Mt Warning. It is estimated that the first flow occurred about 23-21 million years ago <strong>and</strong><br />

comprised an olivine-rich, low viscosity basalt now known as the ‘Lismore basalt’ (Planning Workshop<br />

1983). Most of the basalt has eroded from the ranges to the north of Mullumbimby but some areas of<br />

Lismore basalt still remain in the northern ranges (Chinamans Hill <strong>and</strong> Chincogan). The volcanic plateau to<br />

the west of <strong>Byron</strong> is comprised of Lismore basalt. A second major flow occurred, consisting of a highly<br />

viscous acid flow, which solidified to form rhyolite. To the north of Mullumbimby on Mt Chincogan, a small<br />

area of this rhyolite still remains overlying the Lismore basalt. Goonengerry, Mount Jerusalem <strong>and</strong> Nightcap<br />

National Parks are located on rhyolite-based soils. Volcanic activity from Mt Warning ended about 20<br />

million years ago with the ‘Blue Knob’ basalt forming the last flow. Mt Jerusalem National Park still contains<br />

areas of Blue Knob basalt overlying the rhyolite <strong>and</strong> Lismore basalt layers which in turn cover the Neranleigh-<br />

Fernvale metasediments (Forestry Commission of NSW 1996, Figure 8-1).<br />

Following the cessation of volcanic activity, differential uplift <strong>and</strong> erosion occurred, causing faster water<br />

movement <strong>and</strong> increased erosion in creek <strong>and</strong> river systems. Fluctuations in sea levels during the Quaternary<br />

period caused alluvial deposition of sequences of fluvial <strong>and</strong> marine sediments. When sea levels dropped,<br />

streams carried down eroded material, which was deposited, partly filling valleys. In turn, high sea levels<br />

brought marine sediments into the valley embayments. As sea levels dropped again, further stream material<br />

was deposited over the marine sediments, forming the coastal plain (Planning Workshop 1983).<br />

21

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

2.5 FLORA<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> lies within an area of extremely high biodiversity, the biogeographic province known as the<br />

McPherson-Macleay overlap zone. Botanist Nancy Burbidge first described this zone in 1960 when she was<br />

mapping the biogeographical provinces of Australia (Burbidge 1960). As a result of both climatic <strong>and</strong><br />

geographic conditions within this zone, many species with tropical or temperate origins reach their southern<br />

<strong>and</strong> northern limits respectively.<br />

Within <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> the range of environmental factors such as topography, altitude, aspect, geology <strong>and</strong><br />

climate have produced a diversity of available habitats, which support a high diversity of plants at both the<br />

species <strong>and</strong> community level. More than half the 6,363 vascular plant species identified in NSW occur in<br />

north-eastern NSW. In comparison Tasmania is twice the size of north-eastern NSW but has less than half<br />

the number of vascular plants (Resource <strong>and</strong> Conservation Assessment <strong>Council</strong> 1996). Many of the plant<br />

species occurring in the region are of particular significance for their endemism, rarity, degree of threat,<br />

distributional limits <strong>and</strong> disjunctions <strong>and</strong> attributes of other scientific interest such as primitiveness.<br />

148 plant species are currently recognised as being endemic to north-eastern New South Wales <strong>and</strong> southern<br />

Queensl<strong>and</strong> (Resource <strong>and</strong> Conservation Assessment <strong>Council</strong> 1996). These species include Threatened<br />

species (TSC Act, 1995) such as the Minyon Qu<strong>and</strong>ong Elaeocarpus sp. 2 ‘Minyon’, Hairy Qu<strong>and</strong>ong Elaeocarpus<br />

williamsianus, Davidson’s Plum Davidsonia pruriens var. jerseyana, Smooth Davidson’s Plum Davidsonia sp. A.<br />

(Photo 16), Corokia Corokia whiteana, Spiny Gardenia R<strong>and</strong>ia moorei (Photo 12), Isoglossa Isoglossa eranthemoides<br />

(Photo 14), Lismore Muttonwood Rapanea sp. 1 <strong>and</strong> Peach Myrtle Uromyrtus australis.<br />

The North Coast of NSW (coastal areas east of the Dividing Range between the Hunter River in the south<br />

to the Queensl<strong>and</strong> border in the north) has the highest number of Rare or Threatened plant species in the<br />

State. Using nation-wide conservation assessment <strong>and</strong> coding, 28 species are classed as Endangered, 55 as<br />

Vulnerable <strong>and</strong> 122 as Rare (Briggs <strong>and</strong> Leigh 1996).<br />

The Upper North East NSW region (the Tweed, Brunswick, Richmond <strong>and</strong> Clarence River catchments)<br />

contains high numbers of species that have been identified as ‘significant’ according to criteria developed by<br />

Sheringham <strong>and</strong> Westaway (1995) (Section 5.2 <strong>and</strong> Table 5.3).<br />

Several primitive genera are found in Upper North East NSW. Most of these members of ancient Gondwanan<br />

families are restricted to rainforests. Such genera include Tasmannia from the Winteraceae family, Wilkiea<br />

from Monimiaceae <strong>and</strong> Hicksbeachia from Proteaceae. Hibbertia from the Dilleniaceae family is an example<br />

of a primitive genus not restricted to rainforests (Resource <strong>and</strong> Conservation Assessment <strong>Council</strong> 1996).<br />

Representatives of these families also occur in Africa <strong>and</strong> in South America, attesting to their Gondwanan<br />

origins.<br />

2.6 FAUNA<br />

<strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> is at the centre of one of the richest <strong>and</strong> most diverse regions for vertebrate fauna in Australia.<br />

On a unit/area basis, the NSW North Coast region (north-eastern NSW-south-eastern Queensl<strong>and</strong>, Thackway<br />

<strong>and</strong> Cresswell 1995) has the highest frog, non-Ctenotus skink, snake <strong>and</strong> marsupial species diversity in<br />

Australia (Pianka <strong>and</strong> Schall 1981) <strong>and</strong> the bird species diversity is exceeded only by the Queensl<strong>and</strong> wet<br />

tropics (NSW National Parks <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Service 1995). The reason for this diversity is predominantly due<br />

to palaeogeographical <strong>and</strong> neogeographical factors (CSIRO Division of Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Ecology 1996).<br />

At a palaeogeographic level, all five of the biotas which currently comprise the Australian terrestrial fauna<br />

(Schodde <strong>and</strong> Calaby 1972, Schodde <strong>and</strong> Faith 1991, Schodde 1991) are represented in the region. However,<br />

most species are contributed by three of these – the Torresian, Bassian <strong>and</strong> Tumbunan. The Torresian <strong>and</strong><br />

Bassian biotas merge in the area, recognised as the McPherson-Macleay overlap zone (Burbidge 1960), but<br />

probably the most important of the three from a regional perspective is the Tumbunan. This comprises the<br />

subtropical rainforest biota which was formerly distributed continuously across the continent during wetter<br />

periods (Schodde <strong>and</strong> Calaby 1972, Schodde <strong>and</strong> Faith 1991, Schodde 1991). The Tumbunan fauna is now<br />

22

BYRON FLORA AND FAUNA STUDY, <strong>1999</strong><br />

essentially relictual, having contracted to two main cores centred on the NSW North Coast <strong>and</strong> the Herbert-<br />

Daintree upl<strong>and</strong>s of North East Queensl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> is characterised by species with restricted distributions<br />

<strong>and</strong> specialised ecological requirements. Examples occurring in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> are the Pouched Frog Assa<br />

darlingtoni, Fletcher’s Frog Lechriodus fletcheri, Great Barred Frog Mixophys fasciolatus, Loveridge’s Frog Philoria<br />

loveridgei (Photo 18), Southern Forest Dragon Hypsilurus spinopes (Photo 20), Three-toed Snake-tooth Skink<br />

Coeranoscincus reticulatus, Blue-speckled Forest-skink Eulamprus murrayi (Photo 19), Stephen’s B<strong>and</strong>ed Snake<br />

Holocephalus stephensii (Photo 21), Rose-crowned Fruit-dove Ptilinopus regina (Photo 23), Topknot Pigeon<br />

Lopholaimus antarcticus, Sooty Owl Tyto tenebricosa, Marbled Frogmouth Podargus ocellatus (Photo 26), Albert’s<br />

Lyrebird Menura alberti (Photo 24), Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, Brown Gerygone Gerygone mouki,<br />

Pale-yellow Robin Tregellasia capito, Logrunner Orthonyx temminckii, Paradise Riflebird Ptilorus paradiseus, Green<br />

Catbird Ailuroedus crassirostris, Regent Bowerbird Sericulus chrysocephalus, Red-legged Pademelon Thylogale thetis<br />

<strong>and</strong> Parma Wallaby Macropus parma.<br />

The Torresian fauna of the tropical, grassy savanna woodl<strong>and</strong>s of northern Australia is represented in the<br />

<strong>Shire</strong> by species such as the Rocket Frog Litoria nasuta, Northern Banjo Frog Limnodynastes terraereginae,<br />

Robust Ctenotus Ctenotus robustus, Major Skink Egernia frerei, Brown Tree Snake Boiga irregularis, Freshwater<br />

Snake Tropidonophis mairii, Bar-shouldered Dove Geopelia humeralis, Grass Owl Tyto capensis, Forest Kingfisher<br />

Todirhamphus macleayi, Red-backed Fairy-wren Malura melanocephalus, Little Friarbird Philemon citreogularis,<br />

Blue-faced Honeyeater Entomyzon cyanotis, White-throated Honeyeater Melithreptus albogularis, White-bellied<br />

Cuckoo-shrike Coracina papuensis, White-breasted Woodswallow Artamus leucorhynchus, Chestnut-breasted<br />

Mannikin Lonchura castaneothorax, Common Planigale Planigale maculatus (Photo 28), Northern Brown<br />

B<strong>and</strong>icoot Isoodon macrourus, Hoary Wattled Bat Chalinolobus nigrogriseus <strong>and</strong> Grassl<strong>and</strong> Melomys Melomys<br />

burtoni.<br />

Examples of the Bassian fauna of the eucalypt-dominated sclerophyll forests of southern Australia present<br />

in <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong> are the Common Eastern Froglet Crinia signifera, Brown-striped Frog Limnodynastes peronii,<br />

Lace Monitor Varanus varius, Dark-flecked Garden Sunskink Lampropholis delicata, Eastern Blue-tongued<br />

Lizard Tiliqua scincoides, Red-bellied Black Snake Pseudechis porphyriacus, Wonga Pigeon Leucosarcia melanoleuca,<br />

Yellow-tailed Black-cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus, Crimson Rosella Platycercus elegans, Red-browed<br />

Treecreeper Climacteris erythrops, Superb Fairy-wren Malurus cyaneus, Striated Thornbill Acanthiza lineata, Eastern<br />

Spinebill Acanthorhynchus tenuirostris, Satin Flycatcher Myiagra cyanoleuca, Bassian Thrush Zoothera lunulata,<br />

Spotted-tailed Quoll Dasyurus maculatus, Koala Phascolarctos cinereus (Photo 29)Eastern Pygmy-possum Cercartetus<br />

nanus, Greater Glider Petauroides volans, Eastern Falsistrelle Falsistrellus tasmaniensis <strong>and</strong> Bush Rat Rattus fuscipes.<br />

The two other biota present, the Irian <strong>and</strong> Eyrean, comprise a much smaller complement of species. The<br />

Irian biota, extending from the lowl<strong>and</strong> rainforests <strong>and</strong> savanna woodl<strong>and</strong>s of New Guinea, is represented<br />

in the <strong>Shire</strong> by the Green Tree Frog Litoria caerulea, Superb Fruit-dove Ptilinopus superbus, Rainbow Lorikeet<br />

Trichoglossus haematodus, Little Bronze-cuckoo Chrysococcyx minutillus, White-eared Monarch Monarcha leucotis,<br />

Scarlet Honeyeater Myzomela sanguinolenta, Common Blossom-bat Syconycteris australis, Eastern Tube-nosed<br />

Bat Nyctimene robinsoni (Photo 30) <strong>and</strong> Black Flying-fox Pteropus alecto. Members of the Eyrean fauna of arid<br />

central Australia are mainly recent colonists which have taken advantage of habitats associated with human<br />

settlement. Species present include Burton’s Snake-lizard Lialis burtonis, the Crested Pigeon Ocyphaps lophotes,<br />

Galah Cacatua roseicapilla, Striped Honeyeater Plectorhyncha lanceolata <strong>and</strong> Pied Butcherbird Cracticus nigrogularis.<br />

In addition to the major biota, a narrow section of the <strong>Shire</strong>’s coastal plain constitutes part of a smaller<br />

biogeographic region known as the Wallum (Coaldrake 1961). Wallum supports fire-prone sclerophyllous<br />

vegetation on low-nutrient s<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> is characterised by a small group of vertebrate species represented in<br />

the <strong>Shire</strong> by the Wallum Froglet Crinia tinnula, Freycinet’s Frog Litoria freycineti, Wallum Tree Frog Litoria<br />

olongburensis (Photo 17) <strong>and</strong> Southern Emu-wren Stipiturus malachurus.<br />

Neogeographically, <strong>Byron</strong> <strong>Shire</strong>’s combination of coastal location, wide elevational <strong>and</strong> topographic variation,<br />

fertile soils interspersed with infertile soils, high rainfall <strong>and</strong> mild climatic regime provide conditions resulting<br />

in a mosaic of vegetation communities <strong>and</strong> promoting plant growth throughout the year (Nix 1976), in turn<br />

maximising niches for fauna (CSIRO Division of Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Ecology 1996).<br />

23

A GREENPRINT FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE<br />

3<br />

24<br />

Databases <strong>and</strong> GIS as<br />

basis for data management<br />

3.1 INTRODUCTION<br />

In a time of rapid change it is important to be able to track changes in the environment so that policy too<br />

can adapt. Also, given the large <strong>and</strong> complex nature of the datasets involved in environmental management<br />

it is important that this information can be readily accessed, visualized, summarized <strong>and</strong> updated.<br />

Due to their ability to meet these requirements Geographical Information Systems (GIS) are increasingly<br />

being utilized as a major tool for planning <strong>and</strong> management.<br />

3.2 GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEMS (GIS)<br />

GIS are simply extensions of more traditional data management systems such as relational databases, or in<br />

simplified form, spreadsheets. Unlike these systems however, GIS utilise a graphical interface whereby<br />

database attributes are attached to point, line, or polygon graphical elements. Apart from the benefits of<br />

visualization, <strong>and</strong> a mechanism for advanced data storage <strong>and</strong> retrieval, this functionality also permits<br />

cartographic map production, detailed data interrogation <strong>and</strong> query, <strong>and</strong> spatial modelling.<br />

The spatial nature of GIS facilitates the integration of many disparate datasets. For example, for any single<br />

location there may exist information related to tenure, ownership, slope, soil type, l<strong>and</strong> use, agricultural<br />

suitability, zoning, vegetation type, ecological attributes, rare plants <strong>and</strong> animals. Where resources are limited<br />

<strong>and</strong> potential planning <strong>and</strong> management constraints are significant, it is important to achieve optimal<br />

outcomes. The ability to perform spatial modelling tasks is a unique feature of GIS, which can be used to<br />