ARCH 84312

ARCH 84312

ARCH 84312

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

Arch. <strong>84312</strong><br />

Italian Classicism<br />

Tues./Thurs. 9:00—12:00<br />

Prof. David Mayernik<br />

SEMESTER THEMES<br />

[I ] t seems to be a lesson of history that the commonplace may be understood as a<br />

reduction of the exceptional, but that the exceptional cannot be understood by<br />

amplifying the commonplace.<br />

—Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance, W.W. Norton, 1968, p. 238<br />

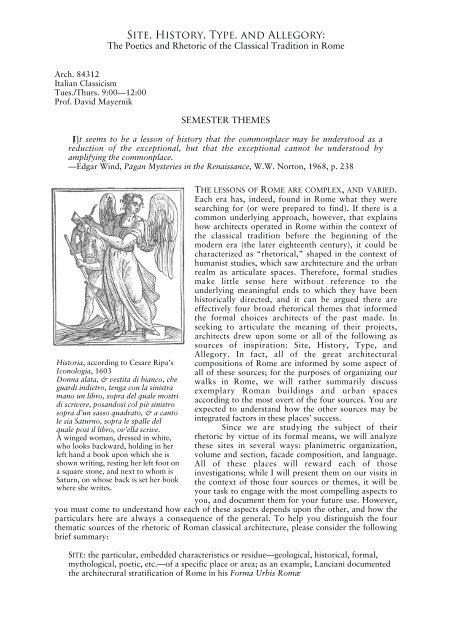

Historia, according to Cesare Ripa’s<br />

Iconologia, 1603<br />

Donna alata, & vestita di bianco, che<br />

guardi indietro, tenga con la sinistra<br />

mano un libro, sopra del quale mostri<br />

di scrivere, posandosi col piè sinistro<br />

sopra d’un sasso quadrato, & a canto<br />

le sia Saturno, sopra le spalle del<br />

quale posi il libro, ov’ella scrive.<br />

A winged woman, dressed in white,<br />

who looks backward, holding in her<br />

left hand a book upon which she is<br />

shown writing, resting her left foot on<br />

a square stone, and next to whom is<br />

Saturn, on whose back is set her book<br />

where she writes.<br />

THE LESSONS OF ROME ARE COMPLEX, AND VARIED.<br />

Each era has, indeed, found in Rome what they were<br />

searching for (or were prepared to find). If there is a<br />

common underlying approach, however, that explains<br />

how architects operated in Rome within the context of<br />

the classical tradition before the beginning of the<br />

modern era (the later eighteenth century), it could be<br />

characterized as “rhetorical,” shaped in the context of<br />

humanist studies, which saw architecture and the urban<br />

realm as articulate spaces. Therefore, formal studies<br />

make little sense here without reference to the<br />

underlying meaningful ends to which they have been<br />

historically directed, and it can be argued there are<br />

effectively four broad rhetorical themes that informed<br />

the formal choices architects of the past made. In<br />

seeking to articulate the meaning of their projects,<br />

architects drew upon some or all of the following as<br />

sources of inspiration: Site, History, Type, and<br />

Allegory. In fact, all of the great architectural<br />

compositions of Rome are informed by some aspect of<br />

all of these sources; for the purposes of organizing our<br />

walks in Rome, we will rather summarily discuss<br />

exemplary Roman buildings and urban spaces<br />

according to the most overt of the four sources. You are<br />

expected to understand how the other sources may be<br />

integrated factors in these places’ success.<br />

Since we are studying the subject of their<br />

rhetoric by virtue of its formal means, we will analyze<br />

these sites in several ways: planimetric organization,<br />

volume and section, facade composition, and language.<br />

All of these places will reward each of those<br />

investigations; while I will present them on our visits in<br />

the context of those four sources or themes, it will be<br />

your task to engage with the most compelling aspects to<br />

you, and document them for your future use. However,<br />

you must come to understand how each of these aspects depends upon the other, and how the<br />

particulars here are always a consequence of the general. To help you distinguish the four<br />

thematic sources of the rhetoric of Roman classical architecture, please consider the following<br />

brief summary:<br />

SITE: the particular, embedded characteristics or residue—geological, historical, formal,<br />

mythological, poetic, etc.—of a specific place or area; as an example, Lanciani documented<br />

the architectural stratification of Rome in his Forma Urbis Romæ

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

HISTORY: the stories and events that have been associated with a particular patron,<br />

founder, institution, building type, place, etc.<br />

TYPE: those general associations and characteristics of a particular building form allied to<br />

function that transcend specific patrons and places<br />

ALLEGORY: those metaphorical allusions to transcendent meaning that became associated<br />

especially with the mythological and Christian traditions in the Renaissance; please note<br />

that it is the nature of allegory to be multivalent, literate, and somewhat obscure.<br />

Again, it should not be assumed that only one of these themes obtain in the places we will visit<br />

to illustrate them—indeed, it is the particular pleasure of Rome that virtually every place is<br />

complex and layered in its meanings—bur rather that I would like you to consider how these<br />

themes might have furnished the primary intent of the rhetoric of the place. At the same time, I<br />

expect your analyses of these places to investigate the ways in which these themes become<br />

intertwined, noting that, for example, a site’s embedded characteristics include the historical<br />

or mythological, history cannot be divorced from place, etc. What is essential in every case is<br />

that you not see the forms as ends in themselves, but rather rhetorical means toward creating a<br />

more articulate urban and rural environment.<br />

[If] a work of art does not instruct overtly through morals, maxims, or demonstrations<br />

of poetic justice, it should be harmoniously well proportioned, reflecting in its own<br />

order and harmony the harmony God created in the universe. In this way, a work of<br />

art, the microcosmic reflection of the macrocosm, expresses and appeals to the most<br />

rational part of the mind, as well as to the highest emotions, and in its total effect<br />

induces in the whole soul and body that balance, harmony, and proportion the soul<br />

ideally should possess in itself, should impose on and share with the body, and should<br />

take pleasure in perceiving and receiving.<br />

— H. James Jensen, The Muses’ Concord: Literature, Music, and the Visual Arts in the<br />

Baroque Age, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976, p. 3<br />

CHRONOLOGICAL OVERVIEW<br />

It must be kept in mind that the usual intent of High Renaissance architects was not to<br />

copy specific Roman buildings but to arrive at their own general canons based on a<br />

composite of Roman examples, canons which were generally [only with regards to the<br />

orders] more rigid than those of Vitruvius himself, and much more rigid than those<br />

illustrated by actual Roman buildings. Since French academic architects tended to adhere<br />

to the principles laid down in the writings of these Renaissance authorities even more<br />

closely than did most Italian architects themselves, the French academic canons of<br />

“classic” design in turn tended to become even more rigidly fixed than those of<br />

Renaissance Italy.<br />

—Donald Drew Egbert, The Beaux-Arts Tradition in French Architecture, Princeton,<br />

1980, p. 106<br />

The broad current of Renaissance architecture in Italy, which started to flow slowly in early<br />

quattrocento Florence and disappeared after a brilliant coda in Piedmont midway through the<br />

eighteenth century, was always anchored on the Idea and experience of Rome. Indeed, what<br />

was produced in Rome from its heyday during the Empire through the eighteenth century<br />

arguably has had more of an impact on the trajectory of Western architectural traditions than<br />

any place on earth. As you are here to specifically study the “classical” tradition, and as the<br />

merits of that tradition as it is manifested in Rome are that it is decidedly whole, integrated,<br />

and meaningful, we cannot simply focus on issues of classical “language” without<br />

understanding context (physical, intellectual, cultural), nor can we study “composition” if we<br />

do not know the rhetorical ends to which these compositions were directed. Thus, the urban<br />

realm, the history of the city and the Church, the culture of Renaissance humanism, the allied<br />

arts, etc. are all essential sub-components of what is ostensibly a seminar dedicated to grasping<br />

the formal principles of classical architecture as it is manifested here.

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

The Renaissance as it is here defined, spanning roughly 350 years from Brunelleschi to<br />

Vittone, is the ideal point of departure for understanding the whole spectrum of the classical<br />

tradition from antiquity to neo-Classicism, since it offers the greatest variety of approaches to<br />

engaging with the past, and the most thoughtful examples of dealing with that most<br />

challenging problem of classicism, the relationship of column and wall. Moreover, the<br />

Renaissance’s ability to arrive at new forms and types out of the raw material of the past<br />

offers us an important model for developing our own approaches to our inheritance. It was in<br />

part the understanding of all art as rhetorical, and therefore driven by its message, that yielded<br />

the fertile variety of approaches to the classical tradition in Rome.<br />

To grasp the Renaissance’s approach to classicism we must therefore resort to the<br />

somewhat problematic idea of “language.” Now, while no visual media can replicate the<br />

structure and meanings of words, the analogies between language and built form in the<br />

classical tradition are close enough to help us unlock the mind of Renaissance architects.<br />

Indeed, they were not merely satisfied to dispose their work with competent grammar and<br />

syntax, they were aiming at a meaningful architecture that was rhetorical and poetic, i.e. that<br />

could explain, convince, exhort, and metaphorically re-present ideas from beyond architecture<br />

itself. It was precisely the aspiration to raise the visual arts to the intellectual standing of the<br />

liberal arts that directed Renaissance artists to adopt the aims and methods of rhetoricians and<br />

poets.<br />

Arguably, the fundamental formal challenge of working with the classical language lies<br />

not in the refinement of the Orders themselves, but in the complex ways in which columns and<br />

walls interact. From the moment ancient Roman architects adopted the post and lintel system<br />

of the Greeks and wed it to their development of a wall-based architecture, the complexities,<br />

ambiguities, and contradictions of that marriage challenged and inspired architects to resolve<br />

the potential conflicts into an ever richer whole. Palladio’s “fugal system of proportions” (in<br />

Wittkower’s words) and Borromini’s contrapuntal compositions were only possible because of<br />

their embrace of the challenges of composing with pilasters, half-columns, and colossal orders<br />

(and, because they could consider the bounds of the canon of the Orders fairly fixed).<br />

Moreover, the license exhibited by the greatest architects of the classical tradition was almost<br />

exclusively rhetorical in impetus: in classical rhetorical theory, one is allowed—even<br />

expected—to depart from the rules in order to reach for greater expressive effect (within the<br />

bounds of decorum, of course).<br />

In addition to the Orders and their deployment, we will study the broader issues of<br />

classical composition, or what an early twentieth century writer might have called the “Grand<br />

Manner,” from antiquity through the era of the Grand Tour. Since the elements of the<br />

classical language serve to order the world, the ways in which they occupy and shape space are<br />

fundamental to understanding the very raison d’être of the classical language—its ability to be<br />

rhetorical, to speak coherently and eloquently of the issues that have occupied the concerns of<br />

thoughtful people and societies for millennia.<br />

In so far as a tradition in architecture can be called classical, it must rest on two<br />

analogies: of the building as a body, and of the design as a re-enactment of some<br />

primitive—or if you would rather—of some archetypal action to which our procedure<br />

might refer. From Vitruvius to Boullée, the texts suggest something of the kind, always<br />

in different contexts, since such ideas do not contain, or even imply, the repertory of<br />

norms and procedures which the constant alteration of circumstances forces you to<br />

renew, to rethink and to alter….<br />

—Joseph Rykwert, “The Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Classical Tradition,” The<br />

Beaux-Arts and Nineteenth Century French Architecture, ed. Robin Middleton, MIT<br />

Press, 1982, p. 17<br />

In concert with our approach of examining the driving themes of Roman classical<br />

architecture, it must also be noted that, at the levels of morphology (form), typology (kind),<br />

and rhetoric (language) there have been, over time, diverse approaches to the inheritance from<br />

the past. One could talk about continuity, inversion, and invention as strategies for dealing<br />

with the legacy of past achievements. When you examine and analyze the places you see this

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

semester, you should reference and seek to document the following very schematic list of how<br />

those strategies might have played out:<br />

CONTINUITY<br />

Morphologies and Typologies:<br />

Insula and Palazzo<br />

Basilica and Church<br />

Temple and Chapel/altar<br />

Triumphal Arch<br />

Villa<br />

Roman Forum and Piazza<br />

City gates<br />

Bridges<br />

Rhetoric:<br />

Orders as genera or types<br />

Disposition of the Orders: Engaged orders, stacked orders<br />

INVERSION<br />

Morphologies and Typologies:<br />

Theater, Colosseum<br />

Temple and Church; Pan-theon vs. Domus Dei<br />

Bath and Church<br />

Imperial Forum and Piazza<br />

Stadium and Piazza<br />

Obelisks<br />

Rhetoric:<br />

meaning of Doric (see Onians)<br />

meaning of the Composite Order<br />

Temple/Church:Inside/Outside (rich/simple)<br />

Rustication<br />

INNOVATION<br />

Morphologies and Typologies:<br />

Palazzo (combining insula and domus elements)<br />

Figural Piazza<br />

Centrally planned church<br />

Nested typologies: e.g. triumphal arch/temple pediment in church facades<br />

Rhetoric:<br />

Orders as a system<br />

Colossal Order; Major/Minor order<br />

Michelangelo’s Ionic<br />

Broken entablatures and pediments; stacked orders and vertical continuity<br />

Illusionistic painting<br />

Bel composto<br />

Fountains<br />

Stairs

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

YOUR TASKS<br />

There is first the archaeological impulse downward into the earth, into the past, the<br />

unknown and recondite, and then the upward impulse to bring forth a corpse whole<br />

and newly restored, re-illuminated, made harmonious and quick.<br />

—Thomas H. Greene, “Resurrecting Rome: The Double Task of the Humanist<br />

Imagination,” Rome in the Renaissance: The City and the Myth, Binghampton, NY:<br />

Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, p. 41<br />

Your overarching task will be to actively engage with these themes and begin to make the city<br />

of Rome your own, by documenting and analyzing some key sites. To begin, one must come to<br />

terms with the way in which Rome continually built upon itself, not ignoring but<br />

incorporating the past in new construction (the “past” here is understood as everything from<br />

physical spolie to abstract classical ideals). This consciousness of the past can help unlock the<br />

ways in which the builders of this compelling landscape understood what they were doing, but<br />

more importantly can also give you a credible approach to your own interventions in the city.<br />

To operate in any urban context, but especially in Rome, you must know the<br />

ground—physical, cultural, historical—upon which you are building.<br />

To engage with this project you will have to do thorough research, the resources for<br />

which will often need to be found outside our library (the faculty and staff can begin to point<br />

you in the right directions) and in the city itself. You are strongly encouraged to take<br />

advantage of the library card for the American Academy in Rome’s Biblioteca that the School<br />

will endeavor to help you secure (please note that you are ultimately responsible for getting it).<br />

The course will be organized around walks in the city (weather permitting),<br />

occasionally preceded by an introductory presentation in class; we will generally include time<br />

for you to draw (whether documentarily or analytically) on site, and you will be expected to<br />

make similar drawings outside of class. These exercises will be done in notebooks that will be<br />

reviewed periodically over the course of the semester. My expectation is that our semester will<br />

be a long conversation about what we are seeing, which entails each of your contribution in<br />

every class and field trip; your vocal participation, or lack thereof, will affect your final grade.<br />

You will, finally, present the results of a major semester-long assignment to the School. More<br />

specifically about each of these tasks:<br />

1. preparation for each class and field trip<br />

read ahead<br />

research/visit site<br />

prepare to discuss the principles in evidence<br />

2. sketchbooks/journals (must be approximately A4 format, vertical preferred), to be<br />

reviewed periodically over the course of the semester and at the end;<br />

notebooks must include: analytical drawings (graphics and notes), documentary<br />

drawings and reconstructions, lecture notes, and supplemental historical information<br />

(written, redrawn or pasted in)<br />

NB: the primary purpose of the sketchbooks for this class is to develop your skills in<br />

analytical drawing; these will be given the most weight in grading<br />

3. semester project:<br />

Architects in Rome have built upon the four themes—site, history, type, allegory—that<br />

will structure our site visits, and it is expected that you will form over the course of the<br />

semester the ability to analyze and document that process in other sites that we will<br />

not visit. To do this project you will need to do significant research in our library and<br />

elsewhere, not to mention on site, in order to unlock the ideas, intentions and<br />

references of the building you choose to focus on.<br />

Choose a significant structure or space in Rome ( only one student per subject, please)<br />

and present an analytique that documents its sources, references, and any unbuilt<br />

projects in ways that explain the intention of its author(s). You must choose a subject<br />

for study by the fourth class of the semester; be prepared at that time to explain why<br />

you choose a particular place. Preferred subjects include (you may propose others but

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

you must explain why in writing, and they are subject to my approval by the end of the<br />

second week):<br />

1. Porta Santo Spirito and/or the Zecca (Banco di S. Spirito)<br />

2. Porta Pia<br />

3. Acqua Paola<br />

4. Ponte Sant’ Angelo<br />

5. Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne<br />

6. Palazzo and Piazza Montecitorio<br />

7. Villa Lante (Janiculum)<br />

8. Villa Medici<br />

9. Orti Farnesiani<br />

10. Accademia degli Arcadi<br />

11. S. Ivo and the Sapienza<br />

12. S. Maria dell’ Orazione e Morte<br />

13. S. Maria Maggiore<br />

14. S. Maria degli Angeli<br />

15. Ospedale di Santo Spirito<br />

16. Ospizio di S. Trinità dei Pellegrini<br />

The final project will be due in Week 10 (see schedule, following).<br />

There will be assigned readings each week, which will be on reserve either in the form of<br />

photocopies or books; these are meant to supplement the talks we will do on site. Some of<br />

those books which you should be referencing this semester include:<br />

Joseph Connors and John Wilton-Ely, Piranesi Architetto<br />

Amato P. Frutaz, Le Piante di Roma<br />

Krautheimer, Frankl, Corbett, Corpus Basilicarum<br />

Marcia Hall, ed., Rome<br />

Richard Krautheimer, Rome: Profile of a City<br />

The Rome of Alexander VII<br />

Rodolfo Lanciani, Forma Urbis Romæ<br />

Paul Letarouilly, Edifices de Rome Moderne<br />

William L. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire I and II<br />

David Mayernik, Timeless Cities<br />

John Onians, Bearers of Meaning<br />

Loren Partridge, The Art of the Renaissance in Rome 1400—1600<br />

Paolo Portoghesi, Roma del Rinascimento<br />

Roma Barocca<br />

John Stamper, The Architecture of Roman Temples<br />

Mark Wilson-Jones, Principles of Roman Architecture<br />

Rudolph Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism<br />

Art & Architecture in Italy, 1600-1750<br />

Sources of Readings by Week (subject to change):<br />

General: David Mayernik, Timeless Cities (esp. pp. 53–58 for the first class)<br />

1. Charles Stinger, The Renaissance in Rome, pp. 254–264 before the first class;<br />

264–282 for second class<br />

2. Joseph Connors, “Alliance and Enmity in Roman Baroque Urbanism,” Römisches<br />

Jahrbuch der Bibliotecha Hertziana [parts 1 and 2]<br />

3. idem [parts 3 and 4]<br />

4. John Onians, “Serlio’s Venice,” Bearers of Meaning<br />

5. David Coffin, The Villa in the Life of Renaissance Rome, Farnesina and Madama<br />

6. John Onians, “Bramante,” Bearers of Meaning<br />

7. Joseph Connors “Virtuoso Architecture in Cassiano’s Rome,” Cassiano Dal<br />

Pozzo’s Paper Museum<br />

8. Rudolph Wittkower, “Bernini,” Art & Architecture in Italy 1600—1750

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

ANALYSIS: WHAT IS IT<br />

analysis noun (pl. -ses): detailed examination of the elements or structure of something,<br />

typically as a basis for discussion or interpretation<br />

• the process of separating something into its constituent elements. Often contrasted<br />

with synthesis .<br />

ORIGIN late 16th cent.: via medieval Latin from Greek analusis, from analuein<br />

‘unloose,’ from ana- ‘up’ + luein ‘loosen.’<br />

—OED<br />

There seems to be a general confusion at our School about what is expected in an analysis<br />

exercise. Like any “creative” act (and analysis is, perforce, “creative” or inventive), it cannot<br />

be precisely codified. At the same time, some of its essential approaches and techniques can be<br />

spelled out, which will follow. But, a priori, my overall expectation is that you will pursue<br />

analysis with a creative, investigative mind, under one guiding rule: you are trying to puzzle<br />

out what is going on that was intended, or at least comprehended, by those who made<br />

whatever it is you are analyzing (it is therefore “objective,” directed toward the object and not<br />

the subject—i.e. you and what you “feel” about it). To be rigorous and rational, analysis<br />

cannot be as subjective as a Rorschach test; it demands, therefore, an understanding of the<br />

context within which the forms were created, or the why of them.<br />

It can be argued that all of the places we will explore this semester attempt to be<br />

synthetic environments, i.e. they strove in one way or another to not be recognized as<br />

composed of discrete pieces. At the same time, each manifests a clear (albeit sometimes<br />

contradictory within the group) attitude toward the disposition and expression of the parts of<br />

which they are composed (from programmatic to architectonic elements). Therefore, to be<br />

credible here your analyses must both pull apart and show how these buildings synthesized<br />

their components.<br />

Some Tactics<br />

Comparison and contrast: look at similar types that take on different forms, or similar<br />

forms for different types<br />

Graphic juxtaposition: to what extent is the same story being told in plan, section and<br />

elevation<br />

Compositional structure: document sequence, rhythm, hierarchies, positive ambiguities<br />

(or multiple readings)<br />

Some Techniques (remember, analysis is graphically reductive by nature)<br />

figure/ground (Nolli), primary/secondary/tertiary, axial/symmetry lines, sequential<br />

overlay, exploded axons, axons generally, juxtaposing two different kinds of graphic<br />

info (e.g. plan and vignette), keyed/”scanned” 1 dwgs. (e.g. ABCBA), etc., etc.<br />

Some Approaches<br />

Process (Design in reverse): try to work out what was intended by the maker(s), or<br />

how they got to the final product (e.g. by assembly, synthesis, transformation, etc.);<br />

not all buildings or places are composed in an additive process (i.e. “buildings made of<br />

other buildings”), but they often do have discrete components (functional or<br />

otherwise); it is a fact in Rome that most of the best architects tried to synthesize, not<br />

distinguish, the diverse parts of which their compositions were made (think of the parts<br />

of the body to the whole)<br />

Relationships: document physical/spatial relationships like bay rhythms, bilateral or<br />

local symmetry, alignments/axes, etc.; remember, in the urban realm these relationships<br />

are as much between buildings as proper to any one building<br />

References: try to work out the sources for the ideas the buildings or spaces depend<br />

upon (typologies, precedents/models from near and far, etc.)<br />

1 scansion noun: the action of scanning a line of verse to determine its rhythm.<br />

• the rhythm of a line of verse.<br />

ORIGIN mid 17th cent.: from Latin scansio(n-), from scandere ‘to climb’ ;

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

FIELD TRIP SKETCHBOOK ASSIGNMENTS<br />

You are of course welcome to explore anything that interests you in your sketchbooks on our<br />

field trips, but the following list is meant to provide an investigative datum upon which you<br />

can build. I will therefore evaluate your sketchbooks first on the basis of the topics that<br />

follow, then on the ones of your choosing.<br />

Field Trip Analysis Topics:<br />

Scenography in Bologna<br />

Sanmichele’s Decorum and Syntax in Verona (City Gates and Palazzi)<br />

Palladio’s Urban Approach in Vicenza<br />

Palladio’s Churches: Theories of Composition<br />

Sansovino’s Rhetoric in the Piazzetta di San Marco<br />

The Palazzo and Its Transformations in Florence: Ruccelai, Strozzi, Medici, Giugni,<br />

Nonfinito, etc.<br />

The Piazza and Its Transformations in Florence: Ss. Annunziata, Sta. Croce, Uffizi<br />

Sacred and Secular Public Space (inside and out) in Siena<br />

SEMESTER GRADES<br />

Class participation (preparation, discussion) 20%<br />

Notebooks (investigation, curiosity, thoroughness) 30%<br />

Project 50%<br />

quality of drawing 15%<br />

quality of information 35%<br />

NAAB CRITERIA<br />

1. ability: Speaking and Writing Skills<br />

2. Ability: Critical Thinking Skills<br />

3. Ability: Graphic Skills<br />

4. Ability: Research Skills<br />

5. Understanding: Formal Ordering Systems<br />

6. ability: Fundamental Design Skills<br />

8. Understanding: Western Traditions<br />

10. Understanding: National and Regional Traditions<br />

11. Ability: Use of Precedents<br />

15. understanding: Sustainable Design<br />

17. ability: Site Conditions<br />

27. understanding: Client Role in Architecture

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

Notes on attendance and out of class visits: since each class will involve a substantial amount<br />

of walking, we need to begin on time; some classes may not begin at via Monterone but<br />

instead at one of our sites; therefore, it is incumbent on you to confirm where the next class<br />

will meet before we end the previous class; late arrivals will count as absences, and after three<br />

unexcused absences you will be subject to a failing grade for the semester. Out of class visits<br />

are required both for your notebooks and for research toward your final project.<br />

ORGANIZATION OF SITE VISITS IN AND OUT OF CLASS BY THEMES:<br />

SITE<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Campidoglio Pza. Navona (Pal. Pamphilj), S.<br />

Maria della Pace, S. Ignazio<br />

Roman Forum<br />

Theater of Marcellus<br />

II. Pza. dei Cavalieri di Malta San Clemente, Lateran<br />

III. Cavalieri di Rodi, Palazzo Scalinata di Spagna, Fontana di Palatine<br />

Venezia<br />

Trevi<br />

HISTORY<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Imperial Fora, Markets<br />

(Museum)<br />

S. Peter’s Domus Aurea and/or<br />

Colosseum<br />

II. Roman Oratory, Casa<br />

Professa<br />

Collegio Romano,<br />

Propaganda Fide<br />

III. Gesù, S. Andrea della Valle S. Maria in Campitelli, Pal. Baths of Diocletian<br />

Mattei<br />

TYPE<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Palazzo Farnese, Spada Palazzo Baldassini, di Firenze,<br />

Borghese<br />

Palazzo Muti-Bussi,<br />

D’Aste<br />

II. Cloister of S. Maria della<br />

Pace, Cancelleria<br />

Sapienza, S. Maria in<br />

Campo Marzio<br />

III. Pantheon and S. Ivo<br />

Tempietto; S. Eligio degli<br />

Orefici<br />

S. Teodoro, S. Agnese,<br />

others<br />

ALLEGORY<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Villa Farnesina, Pal. Corsini Villa Madama Villa Giulia and/or<br />

Palazzo Barberini<br />

II. S. Andrea al Quirinale and<br />

S. Carlino, S. Susanna, S.<br />

Maria della Vittoria<br />

Chigi Chapel, S. Maria and<br />

Piazza del Popolo<br />

S. Giacomo degli<br />

Incurabili<br />

SCHEDULE OF IN-CLASS SITE VISITS BY WEEK:<br />

15/17 Sept. 1. SITE I. Campidoglio; Pza. Navona (Palazzo Pamphilj), S. Maria della Pace,<br />

Pza. S. Ignazio<br />

22/24 Sept. 2. HISTORY I. Imperial Fora, Trajan’s Markets (Museum); St. Peter’s<br />

29 Sep./1 Oct. 3. TYPE I. Palazzo Farnese, Spada; Palazzos Baldassini, di Firenze, Borghese<br />

6/8 Oct. 4. ALLEGORY I.A Villa Farnesina, Pal. Corsini SITE II. Pza. dei Cavalieri di<br />

Malta<br />

27/29 Oct. 5. ALLEGORY I.B Villa Madama HISTORY II. Roman Oratory; Casa Professa<br />

3 Nov. 6. TYPE II. Cloister of S. Maria della Pace, Cancelleria<br />

10/12 Nov. 7. SITE III. Cavalieri di Rodi, Palazzo Venezia; Scalinata di Spagna, Fontana<br />

di Trevi<br />

17/19 Nov. 8. HISTORY III. Gesù, S. Andrea della Valle; S. Maria in Campitelli, Pal.<br />

Mattei<br />

24 Nov. 9. TYPE III. Pantheon, S. Eligio degli Orefici, Tempietto<br />

1/3 Dec. 10. ALLEGORY II. S. Andrea al Quirinale and S. Carlino, S. Susanna, Porta Pia;<br />

Chigi Chapel. S. Maria and Piazza del Popolo<br />

NB: Final projects are due this week; day and time of presentation t.b.d.