Pattern Books Create an American Architecture - Garden State Legacy

Pattern Books Create an American Architecture - Garden State Legacy

Pattern Books Create an American Architecture - Garden State Legacy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

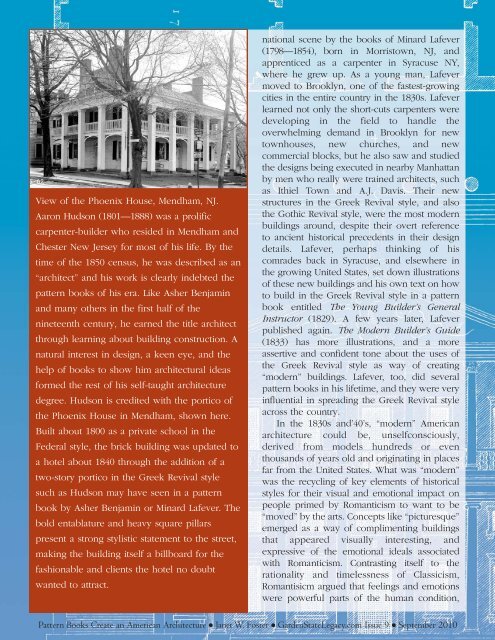

View of the Phoenix House, Mendham, NJ.<br />

Aaron Hudson (1801–1888) was a prolific<br />

carpenter-builder who resided in Mendham <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Chester New Jersey for most of his life. By the<br />

time of the 1850 census, he was described as <strong>an</strong><br />

“architect” <strong>an</strong>d his work is clearly indebted the<br />

pattern books of his era. Like Asher Benjamin<br />

<strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>y others in the first half of the<br />

nineteenth century, he earned the title architect<br />

through learning about building construction. A<br />

natural interest in design, a keen eye, <strong>an</strong>d the<br />

help of books to show him architectural ideas<br />

formed the rest of his self-taught architecture<br />

degree. Hudson is credited with the portico of<br />

the Phoenix House in Mendham, shown here.<br />

Built about 1800 as a private school in the<br />

Federal style, the brick building was updated to<br />

a hotel about 1840 through the addition of a<br />

two-story portico in the Greek Revival style<br />

such as Hudson may have seen in a pattern<br />

book by Asher Benjamin or Minard Lafever. The<br />

bold entablature <strong>an</strong>d heavy square pillars<br />

present a strong stylistic statement to the street,<br />

making the building itself a billboard for the<br />

fashionable <strong>an</strong>d clients the hotel no doubt<br />

w<strong>an</strong>ted to attract.<br />

national scene by the books of Minard Lafever<br />

(1798–1854), born in Morristown, NJ, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

apprenticed as a carpenter in Syracuse NY,<br />

where he grew up. As a young m<strong>an</strong>, Lafever<br />

moved to Brooklyn, one of the fastest-growing<br />

cities in the entire country in the 1830s. Lafever<br />

learned not only the short-cuts carpenters were<br />

developing in the field to h<strong>an</strong>dle the<br />

overwhelming dem<strong>an</strong>d in Brooklyn for new<br />

townhouses, new churches, <strong>an</strong>d new<br />

commercial blocks, but he also saw <strong>an</strong>d studied<br />

the designs being executed in nearby M<strong>an</strong>hatt<strong>an</strong><br />

by men who really were trained architects, such<br />

as Ithiel Town <strong>an</strong>d A.J. Davis. Their new<br />

structures in the Greek Revival style, <strong>an</strong>d also<br />

the Gothic Revival style, were the most modern<br />

buildings around, despite their overt reference<br />

to <strong>an</strong>cient historical precedents in their design<br />

details. Lafever, perhaps thinking of his<br />

comrades back in Syracuse, <strong>an</strong>d elsewhere in<br />

the growing United <strong>State</strong>s, set down illustrations<br />

of these new buildings <strong>an</strong>d his own text on how<br />

to build in the Greek Revival style in a pattern<br />

book entitled The Young Builder’s General<br />

Instructor (1829). A few years later, Lafever<br />

published again. The Modern Builder’s Guide<br />

(1833) has more illustrations, <strong>an</strong>d a more<br />

assertive <strong>an</strong>d confident tone about the uses of<br />

the Greek Revival style as way of creating<br />

“modern” buildings. Lafever, too, did several<br />

pattern books in his lifetime, <strong>an</strong>d they were very<br />

influential in spreading the Greek Revival style<br />

across the country.<br />

In the 1830s <strong>an</strong>d’40’s, “modern” Americ<strong>an</strong><br />

architecture could be, unselfconsciously,<br />

derived from models hundreds or even<br />

thous<strong>an</strong>ds of years old <strong>an</strong>d originating in places<br />

far from the United <strong>State</strong>s. What was “modern”<br />

was the recycling of key elements of historical<br />

styles for their visual <strong>an</strong>d emotional impact on<br />

people primed by Rom<strong>an</strong>ticism to w<strong>an</strong>t to be<br />

“moved” by the arts. Concepts like “picturesque”<br />

emerged as a way of complimenting buildings<br />

that appeared visually interesting, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

expressive of the emotional ideals associated<br />

with Rom<strong>an</strong>ticism. Contrasting itself to the<br />

rationality <strong>an</strong>d timelessness of Classicism,<br />

Rom<strong>an</strong>tisicm argued that feelings <strong>an</strong>d emotions<br />

were powerful parts of the hum<strong>an</strong> condition,<br />

<strong>Pattern</strong> <strong>Books</strong> <strong>Create</strong> <strong>an</strong> Americ<strong>an</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> J<strong>an</strong>et W. Foster <strong>Garden</strong><strong>State</strong><strong>Legacy</strong>.com Issue 9 September 2010