The Ends of Phenomenology: A Graduate ... - University of Sussex

The Ends of Phenomenology: A Graduate ... - University of Sussex

The Ends of Phenomenology: A Graduate ... - University of Sussex

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

!!!!"#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!<br />

!<br />

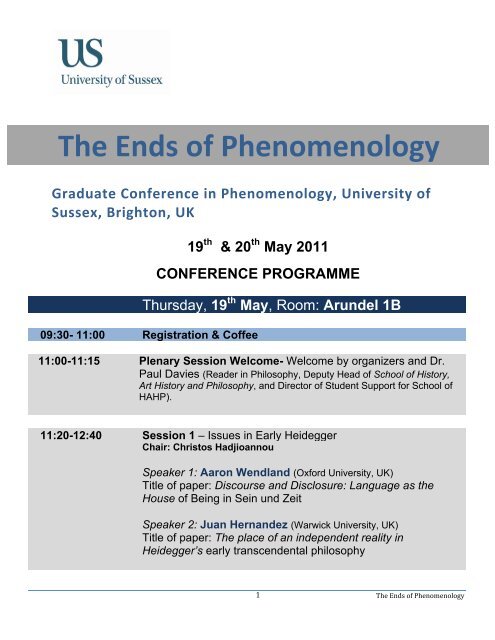

012'324$!5)&*$1$&6$!7&!+#$&),$&)-)./8!9&7:$1(74/!)*!<br />

;3(($!<br />

19 th & 20 th May 2011<br />

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME<br />

Thursday, 19 th May, Room: Arundel 1B<br />

09:30- 11:00 Registration & C<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

11:00-11:15 Plenary Session Welcome- Welcome by organizers and Dr.<br />

Paul Davies (Reader in Philosophy, Deputy Head <strong>of</strong> School <strong>of</strong> History,<br />

Art History and Philosophy, and Director <strong>of</strong> Student Support for School <strong>of</strong><br />

HAHP).<br />

11:20-12:40 Session 1 – Issues in Early Heidegger<br />

Chair: Christos Hadjioannou<br />

Speaker 1: Aaron Wendland (Oxford <strong>University</strong>, UK)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: Discourse and Disclosure: Language as the<br />

House <strong>of</strong> Being in Sein und Zeit<br />

Speaker 2: Juan Hernandez (Warwick <strong>University</strong>, UK)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: <strong>The</strong> place <strong>of</strong> an independent reality in<br />

Heidegger’s early transcendental philosophy<br />

! 0! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

12:40- 13:40 Lunch<br />

13:40- 15:00 Session 2 – Modernist delimitations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong><br />

Chair: Gabriel Martin<br />

15:00- 15:20 C<strong>of</strong>fee Break<br />

Speaker 1: Ari Korhonen (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Helsinki, Finland)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: Humanism or Metaphysics: Derrida on the<br />

Kantian End <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong><br />

Speaker 2: Matthew Bennett (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Essex, UK)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: <strong>The</strong> Beginnings <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong>: did<br />

Nietzsche do phenomenology?<br />

15:20- 16: 40 Session 3 – Issues in Late Heidegger<br />

Chair: Alistair Duncan<br />

16:40-17:00 C<strong>of</strong>fee Break<br />

Speaker 1: Tobias Keiling (Freiburg <strong>University</strong>, Germany)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: <strong>The</strong> Death and the Place <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong>-On<br />

Heidegger’s “<strong>The</strong> End <strong>of</strong> Philosophy and the Task <strong>of</strong> Thinking”<br />

Speaker 2: Andreea Parapuf (Radboud <strong>University</strong>, <strong>The</strong> Netherlands)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: From Phenomenon to the Phenomenal Character<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Event<br />

17:00- 18:20 Session 4 - Embodiment and Realism<br />

Chair: Aaron Wendland<br />

Speaker 1: Jasper Van de Vijver (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Antwerp, Belgium)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: Embodiment and transcendence. Being in place<br />

through the body<br />

! 1! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

18:30- 18:40 Closing Remarks<br />

!<br />

Speaker 2: Lorcan Whitehead (Essex <strong>University</strong>, UK)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: Trying not to Remain Objective<br />

Drinks at IDS Bar (on campus)<br />

Friday, 20 th May, Room: FRISTON 113<br />

8.30- 9:00 Registration and C<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

9:00- 10:20 Session 1 – <strong>Phenomenology</strong> and Art<br />

Chair: Arthur Willemse<br />

10:20- 10:30 C<strong>of</strong>fee Break<br />

Speaker 1: Tim Huntley (<strong>Sussex</strong> <strong>University</strong>, UK)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: “An indolence about existing”: In the sink and<br />

deathly torpor <strong>of</strong> theatre<br />

Speaker 2: Tavi Meraud (Potsdam <strong>University</strong>, Germany)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: <strong>Phenomenology</strong>’s End: <strong>The</strong> Beginning <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

! 2! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

10:30- 12:10 Keynote Speaker<br />

12.10 – 13.20 Lunch Break<br />

!<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Charles Guignon (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> South Florida, USA)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> Paper: Becoming a Person: Hermeneutic<br />

<strong>Phenomenology</strong>’s Contribution<br />

Chair: Dr. Michael Lewis (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sussex</strong>)<br />

13.20 – 14.40 Session 2 – Heidegger and other philosophers<br />

Chair: Zoe Sutherland<br />

14:40- 14:50 C<strong>of</strong>fee break<br />

Speaker 1: Dimitri Kladiskakis (<strong>Sussex</strong> <strong>University</strong>, UK)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: Heidegger and Marx: a dialectic on practicality<br />

Speaker 2: Abraham J. Greenstine (Duquesne <strong>University</strong>, Pittsburg,<br />

USA)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: Aristotle’s Metaphysical Alternative to Heidegger’s<br />

Fundamental Ontology<br />

14:50- 16:10 Session 3 - On historicity and temporality<br />

Chair: Murat Celic<br />

Speaker 1: Keith Whitmoyer (New School for Social Research,<br />

New York, USA)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> Paper: Untimeliness and Transcendental <strong>Phenomenology</strong><br />

Speaker 2: Peter Varga (ELTE <strong>University</strong>, Hungary)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> paper: <strong>The</strong> Historicity and Endgültigkeit <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong>:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong> Husserl<br />

! 3! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

16:10- 16:30 C<strong>of</strong>fee Break<br />

!<br />

16:30- 18:30 Keynote Speaker<br />

Philosophy Society <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sussex</strong><br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Robert Bernasconi (Pennsylvania State <strong>University</strong>)<br />

Title <strong>of</strong> Paper: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Racial Types in Nazi<br />

Germany: Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss's Debt to Husserl<br />

Chair: Dr. Paul Davies (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sussex</strong>)<br />

18:30-18:45 Best Paper Prize and Closing Remarks<br />

18:45- 20:00 Drinks at IDS Bar (on campus)<br />

20.30- Dinner at tba<br />

! 4! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

Abstracts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> Speakers<br />

Name: Aaron Wendland, DPhil candidate at Oxford <strong>University</strong>, Somerville College<br />

Email: aaron.wendland@some.ox.ac.uk<br />

Title: Discourse and Disclosure: Language as the House <strong>of</strong> Being in Sein und Zeit<br />

Abstract: In an attempt to illustrate the extent to which language is the house <strong>of</strong> Being in Sein und Zeit,<br />

this paper begins with an examination <strong>of</strong> the complex and confusing discussion Heidegger actually<br />

produces on discourse and language in his magnum opus. This complexity and confusion stems from<br />

the fact that Heidegger appears to be working with two competing conceptions <strong>of</strong> discourse in Sein und<br />

Zeit: namely, a pragmatic-instrumentalist approach, which treats language as grounded in a prior,<br />

practical understanding <strong>of</strong> the world that is articulated in discourse, and a linguistic-constitutivist point <strong>of</strong><br />

view, which sees language as a condition for any understanding <strong>of</strong> the world whatsoever. Whilst<br />

analyzing Heidegger’s writings on discourse, this paper criticizes the pragmatic model for conflating<br />

discourse with Heidegger’s technical use <strong>of</strong> understanding and failing to appreciate the extent to which<br />

language constitutes our world, whereas the linguistic explication is scrutinized for trivializing the<br />

distinction Heidegger makes between discourse and language and adopting a thin conception <strong>of</strong><br />

linguistic phenomena. Against the aforementioned interpretations, this essay defines discourse as a<br />

distinct communal norm that governs Dasein’s expressive and communicative practices and opens up<br />

her world. Briefly, the idea is that Dasein’s ability to communicate with others enables her to take a<br />

stand on her existence and thereby understand something as something. On this reading, discourse<br />

refers to the transcendental conditions <strong>of</strong> repetition and recognition that make communication and worlddisclosure<br />

possible, but in concrete terms Dasein’s capacity to communicate and disclose the world is a<br />

function <strong>of</strong> her natural language. And ins<strong>of</strong>ar as discourse underwrites Dasein’s use <strong>of</strong> language but<br />

language itself is the site <strong>of</strong> world-disclosure, language is already the house <strong>of</strong> Being in Sein und Zeit.<br />

Name: Juan Pablo Hernández, PhD candidate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Warwick<br />

Email: J.P.Hernandez@warwick.ac.uk<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> place <strong>of</strong> an independent reality in Heidegger’s early transcendental philosophy<br />

Abstract: <strong>The</strong> question whether Heidegger’s philosophy in Being and Time involves either some form <strong>of</strong><br />

idealism or realism, or on the contrary overcomes the Cartesian presuppositions that give rise to such<br />

doctrines has been the source <strong>of</strong> heated and unrelenting debate for many years. This problem is deeply<br />

related to the questions <strong>of</strong> how we are to understand the phenomenological-transcendental character <strong>of</strong><br />

Heidegger’s enterprise, and how exactly this approach is supposed to address traditional metaphysical<br />

concerns. I identify two main types <strong>of</strong> interpretation on the basis <strong>of</strong> a distinction between world-directed<br />

and self-directed approaches originating in the literature on transcendental arguments (Strawson,<br />

Stroud, Cassam). <strong>The</strong> first type <strong>of</strong> reading claims that Heidegger’s theory has metaphysical ambitions<br />

! 5! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

and involves a form <strong>of</strong> idealism (Okrent, Blattner, Hans-Pile, Holfman), whereas the second reads<br />

Heidegger’s enterprise as exclusively concerned with Dasein’s conditions <strong>of</strong> intelligibility (Dreyfus,<br />

Spinosa, Philipse, Cerbone, Carman). I find both approaches wanting and argue that although the<br />

second and more accepted reading is theoretically and exegetically more solid than the first, it ultimately<br />

misconstrues Heidegger’s picture <strong>of</strong> the relation between intelligibility and entities. This reading typically<br />

perceives a problem regarding the compatibility <strong>of</strong> Heidegger’s thinking with realism, and attempts to<br />

provide a solution. I argue that such perception and the attempted solution are expressions <strong>of</strong> a failure to<br />

overcome the Cartesian picture Heidegger criticizes. By drawing attention to certain passages and<br />

emphasizing important similarities with John McDowell’s rejection <strong>of</strong> Cartesianism I propose an<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> Heidegger’s philosophy according to which the conditions <strong>of</strong> intelligibility are to be<br />

understood as granting direct access to the way things are in themselves, thereby making idealism<br />

untenable and a pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> realism pointless, while exorcising any threat <strong>of</strong> restoring a noumenonal reality.<br />

I conclude with some remarks on how this interpretation, in its similarities with McDowell’s philosophy,<br />

provides a novel way <strong>of</strong> understanding the relation between Heidegger’s concepts <strong>of</strong> phenomenon and<br />

entity, and therefore also the role <strong>of</strong> phenomenology in his early thinking.<br />

Name: Ari Korhonen, PhD Candidate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Helsinki<br />

Email: ari.korhonen@helsinki.fi<br />

Title: Humanism or Metaphysics: Derrida on the Kantian End <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong><br />

Abstract: <strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> this paper is to demonstrate, how the early thought <strong>of</strong> Jacques Derrida can be<br />

conceived as an articulation <strong>of</strong> a certain Kantian end <strong>of</strong> phenomenology. As it is well known the thought<br />

<strong>of</strong> Derrida is <strong>of</strong>ten understood as a critic <strong>of</strong> phenomenology and as a part <strong>of</strong> the post-phenomenological<br />

thought. From this point <strong>of</strong> view, the thought <strong>of</strong> Derrida is something that simply comes after the end <strong>of</strong><br />

phenomenology. However, as this paper aims to demonstrate, this criticism presented by Derrida has to<br />

be seen as an operation within a certain historical situation. As Derrida himself wrote, the project <strong>of</strong> his<br />

early thought was to resist the metaphysics <strong>of</strong> presence in its different forms, and by presenting the<br />

readings <strong>of</strong> Husserl to defend the position <strong>of</strong> philosophy. For example, in his introduction to the Husserl’s<br />

Origin <strong>of</strong> Geometry, Derrida demonstrates how the ideality <strong>of</strong> an object consists in the intertwining<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> signification which can not be taken as a present object. According to Derrida, the<br />

Husserlian phenomenology deconstructs the presence <strong>of</strong> ideality and shows how the unity <strong>of</strong> meaningful<br />

world is not present but only in the unity <strong>of</strong> movement. However, in this way Derrida demonstrates how<br />

also Husserl chooses a metaphysical way. Husserl keeps the human ratio as the horizon <strong>of</strong> the<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> signification. As Derrida writes in his <strong>The</strong> <strong>Ends</strong> <strong>of</strong> Man, “the necessity which links the<br />

thinking <strong>of</strong> the phainesthai to the thinking <strong>of</strong> the telos” is evident in the Husserlian phenomenology. <strong>The</strong><br />

aim <strong>of</strong> this paper is to <strong>of</strong>fer a reading <strong>of</strong> early texts <strong>of</strong> Derrida and show the argument concerning the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> phenomenology: even though Husserl deconstructs the presence <strong>of</strong> meaning, he thinks this<br />

movement always within the essence <strong>of</strong> man as its horizon and its telos. In this way the end <strong>of</strong><br />

phenomenology is always a Kantian one, an end to come.<br />

! 6! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

Name: Matthew Paul Bennett, PhD Candidate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Essex<br />

Email: ari.korhonen@helsinki.fi<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> Beginnings <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong>: did Nietzsche do phenomenology?<br />

Abstract: Characterising the distinctive features <strong>of</strong> phenomenology has proved notoriously difficult both<br />

for retrospective histories <strong>of</strong> phenomenology and for those canonical phenomenologists about whom<br />

histories are written. One approach we could take to delimiting phenomenology would be to definitively<br />

identify those in the history <strong>of</strong> philosophy who did practice phenomenology. An extensional definition <strong>of</strong><br />

phenomenology, if achieved, would go a long way to help determine what is characteristic <strong>of</strong> the<br />

phenomenological method. This paper will contribute to such a task by assessing the suggestion made<br />

by some that Nietzsche is a candidate for our list <strong>of</strong> phenomenologists. A relatively small but by no<br />

means insignificant collection <strong>of</strong> Nietzsche readers – including Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Keith<br />

Ansell-Pearson and Peter Poellner – have claimed that Nietzsche should be read as a phenomenologist.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se readers have argued that Nietzsche is a phenomenologist ins<strong>of</strong>ar as he replaces first philosophy<br />

with (non-naturalistic) psychological observations and he suspends the natural attitude.<br />

In order to assess the validity <strong>of</strong> the claim that Nietzsche was a phenomenologist, I will suggest that this<br />

reading is committed to two further claims about Nietzsche. First, the phenomenologist reading must<br />

maintain that Nietzsche’s psychology is a study <strong>of</strong> how the world appears to consciousness. Second, it<br />

must maintain that Nietzsche eschews accounts <strong>of</strong> the generation <strong>of</strong> phenomena in favour <strong>of</strong> accounts <strong>of</strong><br />

the content <strong>of</strong> those phenomena (what Husserl might have called noemata) and the structures<br />

necessary to consciousness (what Husserl might have called noesis). I will suggest that were these<br />

things not true <strong>of</strong> Nietzsche, then it would not make sense to label him a phenomenologist. I will also<br />

give reasons to doubt (though not necessarily insurmountable objections to) both <strong>of</strong> these further claims<br />

<strong>of</strong> the phenomenologist reading <strong>of</strong> Nietzsche.<br />

Name: Tobias Keiling, PhD Candiate at Freiburg <strong>University</strong>, Germany<br />

Email: tobias.keiling@philosophie.uni-freiburg.de<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> Death and the Place <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong>-On Heidegger’s “<strong>The</strong> End <strong>of</strong> Philosophy and the Task<br />

<strong>of</strong> Thinking”<br />

Abstract: “<strong>The</strong> End <strong>of</strong> Philosophy and the Task <strong>of</strong> Thinking” (1964), one <strong>of</strong> Heidegger’s last lectures,<br />

may be said to his philosophical bequest. Through his discussion <strong>of</strong> Hegel’s and Husserl’s determination<br />

<strong>of</strong> the “matter <strong>of</strong> thinking,” Heidegger deliberates the fate <strong>of</strong> phenomenology at the proclaimed “end <strong>of</strong><br />

philosophy.” In opening up philosophy so as to attend to the matter <strong>of</strong> thinking (identified as subjectivity),<br />

both phenomenologists exhibit an approach still relevant for what Heidegger calls “the task <strong>of</strong> thinking”:<br />

to understand what it means to determine a matter <strong>of</strong> thinking responding to what calls to be thought.<br />

Thus tasked, phenomenology remains “the possibility <strong>of</strong> thinking corresponding to the claims <strong>of</strong> the<br />

matter <strong>of</strong> thinking.” <strong>Phenomenology</strong> persists as a possibility precisely because philosophy ends. In such<br />

a way, classical phenomenology is redefined by its very end.<br />

To determine this opening redetermination, I wish to elaborate on two ideas: the first is Heidegger’s<br />

claim that the end is to be understood as a gathering place, like the tip <strong>of</strong> a spear concentrating its force<br />

to a single point. <strong>The</strong> end <strong>of</strong> phenomenology would accordingly gather its different historical shapes and<br />

! 7! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

reveal their common thrust not as their “last,” but as their “first” and “utmost possibility.” Following John<br />

Sallis, I wish to relate this mention <strong>of</strong> the “utmost possibility” <strong>of</strong> philosophy to his account <strong>of</strong> Beingtowards-Death<br />

in Being and Time, where death is determined as the “utmost possibility” <strong>of</strong> Dasein.<br />

Heidegger is intent to show how death is constantly present in authentic being—if an analogy can be<br />

drawn, can it be said that what Heidegger describes later is the persistent awareness <strong>of</strong> phenomenology<br />

for its death, dying, as Heidegger feared, by becoming “cybernetics?” And if so, how does this relate to<br />

the thinking <strong>of</strong> place announced in “<strong>The</strong> End <strong>of</strong> Philosophy... ?”<br />

Name: Andreea Parapuf, PhD Candidate, Radboud <strong>University</strong> Nijmegen<br />

Email: a.parapuf@phil.ru.nl<br />

Title: From Phenomenon to the Phenomenal Character <strong>of</strong> the Event<br />

Abstract: In this presentation I would like to address the main question <strong>of</strong> the conference – is there an<br />

end <strong>of</strong> phenomenology and what would be the reasons and the criteria for setting such boundaries – by<br />

focusing on one particular case: the transformations that take place in Heidegger’s philosophy in the<br />

move from the phenomenological and hermeneutic ontology to the ‘post-phenomenological’ moment<br />

known as Ereignis-Denken. I propose to look at Heidegger’s case as an exemplification <strong>of</strong> how the task<br />

<strong>of</strong> phenomenology remains alive and guides a non-phenomenological or post-phenomenological<br />

philosophy. It is broadly acknowledged that starting from the 1930’s onwards, Heidegger famously gave<br />

up both phenomenology and hermeneutics, the two crucial methods <strong>of</strong> Being and Time. In this paper I<br />

seek to challenge the view according to which the new approach <strong>of</strong> “the thinking <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> being”<br />

(seinsgeschichliches Denken) makes the end <strong>of</strong> the hermeneutic phenomenology unavoidable.<br />

<strong>The</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> this presentation is to show and to investigate the presence <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong><br />

phenomenological and hermeneutic elements in the non-phenomenological or post-phenomenological<br />

thinking <strong>of</strong> Ereignis. I will proceed by pointing out a number <strong>of</strong> similarities between the task <strong>of</strong><br />

phenomenology in Being and Time and a number <strong>of</strong> remarks that we can find in later texts or lectures <strong>of</strong><br />

Heidegger. <strong>The</strong> elements that I will compare are: a) the definition <strong>of</strong> logos in Being and Time with the<br />

description <strong>of</strong> logos and legein in the 1951 lecture entitled Logos (Heraklit, Fragment 50). b) the second<br />

element that I will investigate is the idea <strong>of</strong> “das Sichzeigende,” a term which, surprisingly enough,<br />

describes both the phenomenon in Being and Time and the thing itself (die Sache) or being as Ereignis<br />

in Heidegger’s later works. What do these similarities tell us about the specific nature <strong>of</strong> the relation<br />

between the method and the object <strong>of</strong> phenomenology?<br />

Name: Jasper Van de Vijver, PhD Candidate at <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Antwerp<br />

Email: jasper.vandevijver@ua.ac.be<br />

Title: Embodiment and transcendence. Being in place through the body<br />

Abstract: In my talk, I would like to explore the seemingly commonsensical question ‘Where is here?’<br />

from a phenomenological perspective. I will sketch the problem by introducing the views <strong>of</strong> Husserl and<br />

Heidegger on this issue.<br />

! 8! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

According to Husserl, the embodied subject constitutes the absolute ‘center’ <strong>of</strong> its field <strong>of</strong> experience,<br />

which is orientated around the I. Being ‘here’ thus comes down to being where the body is: being always<br />

in the middle <strong>of</strong> things as the ‘zero-point <strong>of</strong> orientation’. This being-here is absolute, in the sense that I<br />

can never not be here; it is impossible for me not to experience the world from this absolute here-point.<br />

Heidegger’s phenomenology <strong>of</strong> spatiality implicitly but all too clearly constitutes a criticism <strong>of</strong> Husserl’s.<br />

Whereas Husserl stresses the embodied character <strong>of</strong> the here- point as the place from which we relate<br />

to the things around us, Heidegger holds that we always already transcend it towards the world, and that<br />

we never really experience our body as the ‘place where we are’. Heidegger polemically states that<br />

when we say ‘here’, we do not refer to ourselves or our body as a ‘zero-point’, but to the ‘there’ <strong>of</strong> the<br />

particular situation we are engaged in. According to him, our body is not the nearest, but the most distant<br />

from us.<br />

I argue that both approaches have something to <strong>of</strong>fer and do not exclude one another. Being here is<br />

indeed being-in-place, as Heidegger highlights. However, it is clear that this place can only be given<br />

through an embodied point <strong>of</strong> view, as Husserl holds. I will argue that what is important here is that this<br />

point <strong>of</strong> view is itself perceptually absent. <strong>The</strong> body is not identical with the ‘here’, but gives way for the<br />

places which are opened up by it.<br />

Name: Lorcan Whitehead, PhD Candidate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Essex<br />

Email: ljwhit@essex.ac.uk<br />

Title: Trying not to Remain Objective<br />

Abstract: In the opening section <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Perception, Merleau-Ponty <strong>of</strong>fers a critique <strong>of</strong> the<br />

‘constancy hypothesis’ which represents his idiosyncratic enactment <strong>of</strong> the famous phenomenological<br />

reduction. <strong>The</strong> constancy hypothesis <strong>of</strong>fers tacit support for the notion <strong>of</strong> an objective world prior to<br />

experience, by claiming to bridge the gap between that world and our experience <strong>of</strong> it. However, it<br />

encounters problems when faced with ambiguous phenomena which do not neatly match up with the<br />

stimuli that supposedly give rise to them. Because the constancy hypothesis cannot adequately account<br />

for such phenomena, Merleau-Ponty insists that it must be rejected, along with the notion <strong>of</strong> an objective<br />

world prior to experience that it is designed to support. Instead, Merleau-Ponty insists that the<br />

perceptual world must be seen as primary, and the objective models <strong>of</strong>fered by scientific and analytic<br />

reflection as being derived from it. This critique, and the claim for the primacy <strong>of</strong> the perceptual world,<br />

will be familiar to most students <strong>of</strong> Merleau-Ponty. However, the consequences <strong>of</strong> his claim for the<br />

essential ambiguity <strong>of</strong> perceptual experience have not been fully appreciated by most commentators.<br />

For Merleau-Ponty’s claim for the primacy <strong>of</strong> the perceptual world makes his notion <strong>of</strong> ambiguity far more<br />

radical than the idea that we can simply approach things in different ways. This is because he claims<br />

that the perceptual thing is itself “constituted in the hold which my body takes upon it” (PP 373). Thus<br />

ambiguity is not a mere feature <strong>of</strong> perspectives, but a fundamental aspect <strong>of</strong> things themselves. In this<br />

paper, I will suggest that taking seriously this radical notion <strong>of</strong> ambiguity is the real lesson arising from<br />

<strong>Phenomenology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Perception; and that doing so ought to have pr<strong>of</strong>ound consequences for our<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> notions such as objectivity, rationality and truth.<br />

! 09! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

Name: Tim Huntley, PhD Candidate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sussex</strong><br />

Email: tinderbox19-05@yahoo.co.uk<br />

Title: “An indolence about existing”: In the sink and deathly torpor <strong>of</strong> theatre<br />

Abstract: When Levinas writes that “the fatality <strong>of</strong> the tragedy <strong>of</strong> antiquity becomes the fatality <strong>of</strong><br />

irremissible being” we might assume him to mark a movement from a theatre <strong>of</strong> essences to a theatre <strong>of</strong><br />

existence. Although Levinas certainly troubles over the inescapability <strong>of</strong> our being, his comments on<br />

theatre in Existence and Existents (1947) suggest a form that differs from the representational approach<br />

one might find under a phenomenological analysis <strong>of</strong> theatre's adumbrations.<br />

Levinas' contention is that theatrical performance should be distinguished from the 'self-possession <strong>of</strong> a<br />

beginning'. Existence is a particular continuity that, once begun, can be broken, whereas the life <strong>of</strong><br />

theatre cannot be interrupted. As such, theatre, for Levinas, is little more than a game. Discussion <strong>of</strong><br />

theatrical performance cannot prolong the theatrical event and so phenomenology might almost exhaust<br />

theatre's aspectival potential. <strong>The</strong> conclusion, risk, and therefore the unpardonable thing about theatre,<br />

is that it can sink into nothingness.<br />

I will suggest that although theatre is granted no access to the metaphysical concerns <strong>of</strong> his project,<br />

Levinas nonetheless leaves a slender opening which remains in the theatrical space after the<br />

performance's end. I will argue that the notion <strong>of</strong> the end in theatre might have a more troubling<br />

continuity than Existence and Existents allows. It is this very sense <strong>of</strong> continuity, I will argue, that Levinas<br />

imports as metaphor into his account <strong>of</strong> the inescapable “perpetuity <strong>of</strong> the drama <strong>of</strong> existence” and which<br />

might arguably be returned to and considered on the stage.<br />

I will consider whether the finite span <strong>of</strong> theatrical performance might not be dissimilar to the account <strong>of</strong><br />

indolence that Existence and Existents <strong>of</strong>fers. This would be an intemperate form <strong>of</strong> indolence that<br />

embraces its own finality, not as a fatality but as an urgent drive towards its inescapable ending.<br />

Name: Tavi Meraud, Masters student Universität Potsdam<br />

Email: another.neologism@gmail.com<br />

Title: <strong>Phenomenology</strong>’s End: <strong>The</strong> Beginning <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

Abstract: In the generation <strong>of</strong> phenomenologists immediately following Husserl, there were several<br />

aestheticians, philosophers who produced significant texts that tried to bring phenomenology together<br />

with aesthetic concerns.<br />

More recently, however, there has been sporadic but ever growing interest in understanding what<br />

Husserl himself had to say about aesthetics, in particular the claims <strong>of</strong> his 1907 letter to the poet<br />

H<strong>of</strong>mannsthal. <strong>The</strong> sensational claims <strong>of</strong> the letter have either been examined in light <strong>of</strong> its famous<br />

recipient or in the service <strong>of</strong> philosophy—but, as Husserl himself implies—what <strong>of</strong> art as philosophy?<br />

! 00! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

My paper, too, begins with this letter, but the intention is not to construct yet another phenomenological<br />

aesthetics, but rather to argue that aesthetics, and concerns about art, is the important descendent <strong>of</strong><br />

Husserl’s phenomenology.<br />

First, I follow Husserl’s fascination with the artist, who he believes to be uniquely privy to the eidetic<br />

insight, via her experience <strong>of</strong> Phantasie, that is otherwise only available through abandoning the natural<br />

attitude and bracketing the world, i.e. the reduction. Phantasie can be understood as the propaedeutic to<br />

the reduction at heart <strong>of</strong> Husserl’s phenomenology and its transcendental consequences. In brief, I<br />

establish an account <strong>of</strong> how art, both the practice and experience <strong>of</strong>, can itself be understood as a<br />

primordially critical examination <strong>of</strong> perception and consequently world constitution in the same sense<br />

that Husserl envisioned his phenomenology to be.<br />

Hence my suggestion that art picks up right where Husserl’s phenomenology ends, i.e. Husserl’s own<br />

struggle to constantly defend his phenomenology against accusations <strong>of</strong> it being idealism.<br />

Thus, to close, I briefly discuss some ways in which art carries on the torch, which Husserl’s<br />

phenomenology lit, by examining a selection <strong>of</strong> art practices that might have transcendental implications.<br />

Art is, I want to argue, the “transcendental clue”, which leads to the transcendental investigation that is<br />

phenomenology, that Husserl mentions in §150 <strong>of</strong> his 1913 Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie.<br />

Name: Dimitrios Kladiskakis, PhD Candidate at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sussex</strong><br />

Email: D.Kladiskakis@sussex.ac.uk<br />

Title: Heidegger and Marx: a dialectic on practicality.<br />

Abstract: Both Marx and Heidegger have founded their theories on the inseparability between man and<br />

his surroundings. In the case <strong>of</strong> Heidegger, the point <strong>of</strong> entry for the exploration <strong>of</strong> the question <strong>of</strong> being<br />

is a departure from the Cartesian understanding <strong>of</strong> the subject and object. Namely, in 'Being and Time'<br />

Heidegger introduces the concept <strong>of</strong> the 'ready-to-hand', that is, things as they are immediately and nonreflectively<br />

used, and at the same time envisions man as inseparable from the world. For Marx, on the<br />

other hand, it is productive activity that defines man as a historical being, and therefore, the relationship<br />

between man and what is immediately useful is similarly emphasised.<br />

In this paper, I will attempt to draw parallels between these two approaches. In detail, I will argue that<br />

Marx's conception <strong>of</strong> productive activity as marking the beginning <strong>of</strong> human history, and therefore as the<br />

birth <strong>of</strong> historical man himself, can be seen as complimentary to Heidegger's exploration <strong>of</strong> practical<br />

everyday life as a primary mode <strong>of</strong> being. In particular, I will proceed to focus on the primacy <strong>of</strong> the<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> 'equipment' and 'production' as these appear in Heidegger's 'Being and Time' and Marx and<br />

Engels' 'German Ideology' respectively, and look into the possibility <strong>of</strong> a conceptual unification <strong>of</strong> the two<br />

notions. <strong>The</strong> paper will therefore begin with a dialectic which will outline the aforementioned concepts <strong>of</strong><br />

'equipment' and 'production' and emphasise their importance to the understanding <strong>of</strong> the human<br />

ontological situation. After this assertion, a constructive dialogue will be attempted between the two,<br />

based on the primacy <strong>of</strong> practical activity, and finally a critical conclusion will discuss the possibilities <strong>of</strong> a<br />

concrete synthesis and elaborate on its consequences.<br />

! 01! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

Name: Abraham Jacob Greenstine, PhD Candidate at Duquesne <strong>University</strong><br />

Email: greenstinea@duq.edu<br />

Title: Aristotle’s Metaphysical Alternative to Heidegger’s Fundamental Ontology<br />

Abstract: Heidegger’s Being and Time changed the landscape <strong>of</strong> phenomenology by bringing the<br />

question <strong>of</strong> the meaning <strong>of</strong> being to the forefront <strong>of</strong> philosophy. However, he enters into this question by<br />

taking up a particular kind <strong>of</strong> being, namely Dasein, and thus most <strong>of</strong> Being and Time engages in an<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> Dasein. Despite this, Heidegger insists that this project is fundamental ontology, and not<br />

a sort <strong>of</strong> anthropology. I want to argue that in Being and Time Heidegger (semi-consciously) follows a<br />

path which is suggested, but not taken, by Aristotle in the Metaphysics. In the Metaphysics Aristotle<br />

says that there are four meanings <strong>of</strong> being, namely the accidental, the true, the figures <strong>of</strong> predication,<br />

and the actual/potential (!.2). However, Aristotle only takes up being as the true twice: he first addresses<br />

and discards it in !.4. It next comes up at ".10, after the thorough analyses <strong>of</strong> being as substance and<br />

as actuality; here Aristotle surprisingly says truth is the #$%&'()() (strictest or most governing) meaning<br />

<strong>of</strong> being. Interpretations <strong>of</strong> Metaphysics have typically ignored this passage <strong>of</strong> the text, but Heidegger’s<br />

Being and Time takes up being as true as the guiding thread <strong>of</strong> fundamental ontology (cf. VI.44).<br />

However, I want to argue for a new reading <strong>of</strong> ".10 which interprets #$%&'()() as referring to our human<br />

state; hence in this reading being as the true is better known to us, but not better known simply (cf. *.2).<br />

This interpretation illustrates that phenomenology has been implicitly dominated by being as the true,<br />

which Heidegger takes up explicitly in his analysis <strong>of</strong> Dasein, and also shows that this is misguided.<br />

However, it would be naïve to simply return to a ready-made Aristotelian ontology or theology. Instead, I<br />

want to suggest that we need to reawaken the overlooked aspect <strong>of</strong> Aristotelian metaphysics as the<br />

sought science (*.2).<br />

Name: Keith Whitmoyer, PhD Candidate at New School for Social Research<br />

Email: whitmoyerk@gmail.com<br />

Title: <strong>Phenomenology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Perception, Untimeliness and Transcendental Philosophy<br />

Abstract: This essay argues that <strong>Phenomenology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Perception develops an account <strong>of</strong> temporality that<br />

attempts to extricate the project <strong>of</strong> transcendental phenomenology from what one might call the<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> “timeliness.” While such a philosophy makes a claim to being on time by presupposing a<br />

certain sense <strong>of</strong> the a priori and evidence, a sense designed to guarantee the unmediated contact<br />

between thought and world and thereby secure an eternal and apodictic ground for philosophy, Merleau-<br />

Ponty’s pivotal text <strong>of</strong>fers a philosophy <strong>of</strong> “lateness” that attempts to recover the “temporal thickness” <strong>of</strong><br />

transcendental philosophy and which thereby recognizes the constitutive opacity and transcendence <strong>of</strong><br />

the ground it seeks to elaborate. By examining Le sentir, Le cogito, and La temporalité, we see that<br />

Merleau-Ponty’s account <strong>of</strong> temporality plays a crucial role in elaborating the themes <strong>of</strong> sense-genesis,<br />

evidence, and the a priori. By bringing his account <strong>of</strong> temporality as the autoconstitutive passage <strong>of</strong> an<br />

écoulement, flow, and an éclatement, explosion, to bear on these themes, Merleau-Ponty attempts to<br />

show that the secure transcendental ground sought by the philosophy <strong>of</strong> timeliness is impossible. In<br />

other words, the philosophy <strong>of</strong> lateness recognizes the impossibility <strong>of</strong> coinciding with the conditions <strong>of</strong><br />

possibility for experience and for philosophy and thus recognizes its task as unfinalizable and<br />

! 02! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!

!<br />

!<br />

!<br />

incomplete. It is in this sense, then, that Merleau-Ponty will famously remark that the phenomenological<br />

reduction cannot be completed and that the task <strong>of</strong> a radical inquiry is, as he says referencing Husserl, a<br />

perpetual beginning. Moreover, in “Brouillon d’une rédaction,” Merleau-Ponty notes that lateness defines<br />

philosophical interrogation, which is “too late for knowing the naïve world which was before it” (Merleau-<br />

Ponty, 1996, 358). <strong>Phenomenology</strong> <strong>of</strong> Perception therefore already introduces a revision <strong>of</strong><br />

transcendental philosophy that is further developed in his later work.<br />

Name: Peter Andras Varga, PhD Candidate at ELTE-<strong>University</strong> Budapest<br />

Email: skuteos@gmail.com<br />

Title: <strong>The</strong> Historicity and Endgültigkeit <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phenomenology</strong>: <strong>The</strong> Case <strong>of</strong> Husserl<br />

Abstract: One <strong>of</strong> the most intriguing features <strong>of</strong> phenomenology, in comparison with other philosophical<br />

movements, is its special relation to its founding father, Edmund Husserl. It is universally agreed that<br />

phenomenology was made possible by a decisive breakthrough initiated by Husserl; yet almost every<br />

phenomenologists, even Husserl’s closest associates, tried to overcome him. <strong>Phenomenology</strong> is the<br />

history <strong>of</strong> Husserlian heresies: Husserl is both continuously rejected and rediscovered.<br />

This ambivalent relation is apparently rooted in Husserl’s idea <strong>of</strong> philosophy that is thought to be unable<br />

to accommodate phenomenology as a living philosophy. As I believe that there is a significant<br />

discrepancy between Husserl’s own idea <strong>of</strong> philosophy and what was imputed to him by the subsequent<br />

generations <strong>of</strong> phenomenologists; I argue that a revisiting <strong>of</strong> Husserl’s ideas on the historicity and<br />

Endgültigkeit <strong>of</strong> phenomenology might prove relevant for our present understanding <strong>of</strong> phenomenology<br />

and its ends.<br />

First, I explore a historical episode that shows Husserl’s awareness <strong>of</strong> the fragmentary character <strong>of</strong> his<br />

oeuvre and its implications. In the late 1920s Husserl corresponded with Misch, who supervised the<br />

critical edition <strong>of</strong> Dilthey’s literary estate. Husserl reflected on its editorial principles, which, at a closer<br />

look, reveal surprising resemblances to our modern framework used when reading historical authors like<br />

Husserl. <strong>The</strong> study <strong>of</strong> Husserl’s letters shows that he was far from propagating an immutable philosophia<br />

perennis and that he was conscious <strong>of</strong> the problem that the history <strong>of</strong> philosophy poses for the<br />

independent thinker.<br />

This problem came to the fore during Husserl’s preparation <strong>of</strong> the Crisis. I propose an interpretation <strong>of</strong><br />

Husserl’s Crisis and its context from this angle. <strong>The</strong> crucial point is that Husserlian phenomenologists<br />

are able to learn from the history <strong>of</strong> philosophy without surrounding their special commitments. In order<br />

to support this interpretation, I focus on Husserl’s analyses <strong>of</strong> various interpretive communities.<br />

In sum, Husserl’s phenomenological philosophy could be closer to the historical approach to philosophy<br />

than usually assumed; and the way <strong>of</strong> doing phenomenology through the study <strong>of</strong> history might give a<br />

genuine chance for reinvigorating phenomenology – while revisiting Husserl again.<br />

! 03! ! "#$!%&'(!)*!+#$&),$&)-)./!