Det One - Force Recon Association

Det One - Force Recon Association

Det One - Force Recon Association

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Training 37<br />

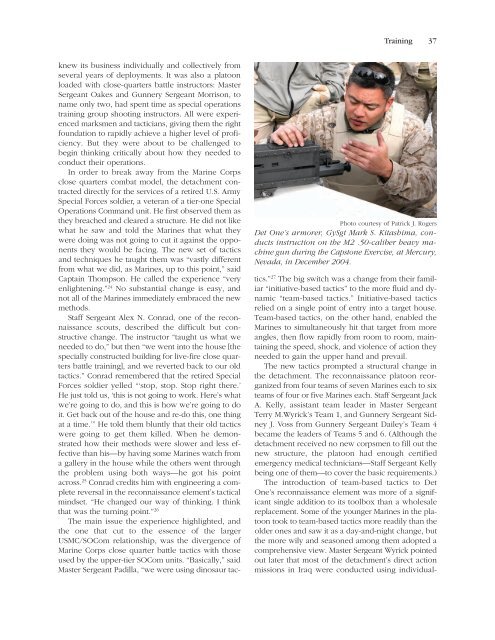

Photo courtesy of Patrick J. Rogers<br />

<strong>Det</strong> <strong>One</strong>’s armorer, GySgt Mark S. Kitashima, conducts<br />

instruction on the M2 .50-caliber heavy machine<br />

gun during the Capstone Exercise, at Mercury,<br />

Nevada, in December 2004.<br />

knew its business individually and collectively from<br />

several years of deployments. It was also a platoon<br />

loaded with close-quarters battle instructors: Master<br />

Sergeant Oakes and Gunnery Sergeant Morrison, to<br />

name only two, had spent time as special operations<br />

training group shooting instructors. All were experienced<br />

marksmen and tacticians, giving them the right<br />

foundation to rapidly achieve a higher level of proficiency.<br />

But they were about to be challenged to<br />

begin thinking critically about how they needed to<br />

conduct their operations.<br />

In order to break away from the Marine Corps<br />

close quarters combat model, the detachment contracted<br />

directly for the services of a retired U.S. Army<br />

Special <strong>Force</strong>s soldier, a veteran of a tier-one Special<br />

Operations Command unit. He first observed them as<br />

they breached and cleared a structure. He did not like<br />

what he saw and told the Marines that what they<br />

were doing was not going to cut it against the opponents<br />

they would be facing. The new set of tactics<br />

and techniques he taught them was “vastly different<br />

from what we did, as Marines, up to this point,” said<br />

Captain Thompson. He called the experience “very<br />

enlightening.” 24 No substantial change is easy, and<br />

not all of the Marines immediately embraced the new<br />

methods.<br />

Staff Sergeant Alex N. Conrad, one of the reconnaissance<br />

scouts, described the difficult but constructive<br />

change. The instructor “taught us what we<br />

needed to do,” but then “we went into the house [the<br />

specially constructed building for live-fire close quarters<br />

battle training], and we reverted back to our old<br />

tactics.” Conrad remembered that the retired Special<br />

<strong>Force</strong>s soldier yelled “‘stop, stop. Stop right there.’<br />

He just told us, ‘this is not going to work. Here’s what<br />

we’re going to do, and this is how we’re going to do<br />

it. Get back out of the house and re-do this, one thing<br />

at a time.’” He told them bluntly that their old tactics<br />

were going to get them killed. When he demonstrated<br />

how their methods were slower and less effective<br />

than his—by having some Marines watch from<br />

a gallery in the house while the others went through<br />

the problem using both ways—he got his point<br />

across. 25 Conrad credits him with engineering a complete<br />

reversal in the reconnaissance element’s tactical<br />

mindset. “He changed our way of thinking. I think<br />

that was the turning point.” 26<br />

The main issue the experience highlighted, and<br />

the one that cut to the essence of the larger<br />

USMC/SOCom relationship, was the divergence of<br />

Marine Corps close quarter battle tactics with those<br />

used by the upper-tier SOCom units. “Basically,” said<br />

Master Sergeant Padilla, “we were using dinosaur tactics.”<br />

27 The big switch was a change from their familiar<br />

“initiative-based tactics” to the more fluid and dynamic<br />

“team-based tactics.” Initiative-based tactics<br />

relied on a single point of entry into a target house.<br />

Team-based tactics, on the other hand, enabled the<br />

Marines to simultaneously hit that target from more<br />

angles, then flow rapidly from room to room, maintaining<br />

the speed, shock, and violence of action they<br />

needed to gain the upper hand and prevail.<br />

The new tactics prompted a structural change in<br />

the detachment. The reconnaissance platoon reorganized<br />

from four teams of seven Marines each to six<br />

teams of four or five Marines each. Staff Sergeant Jack<br />

A. Kelly, assistant team leader in Master Sergeant<br />

Terry M.Wyrick’s Team 1, and Gunnery Sergeant Sidney<br />

J. Voss from Gunnery Sergeant Dailey’s Team 4<br />

became the leaders of Teams 5 and 6. (Although the<br />

detachment received no new corpsmen to fill out the<br />

new structure, the platoon had enough certified<br />

emergency medical technicians—Staff Sergeant Kelly<br />

being one of them—to cover the basic requirements.)<br />

The introduction of team-based tactics to <strong>Det</strong><br />

<strong>One</strong>’s reconnaissance element was more of a significant<br />

single addition to its toolbox than a wholesale<br />

replacement. Some of the younger Marines in the platoon<br />

took to team-based tactics more readily than the<br />

older ones and saw it as a day-and-night change, but<br />

the more wily and seasoned among them adopted a<br />

comprehensive view. Master Sergeant Wyrick pointed<br />

out later that most of the detachment’s direct action<br />

missions in Iraq were conducted using individual-