addressing the global health workforce crisis: challenges for france ...

addressing the global health workforce crisis: challenges for france ...

addressing the global health workforce crisis: challenges for france ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

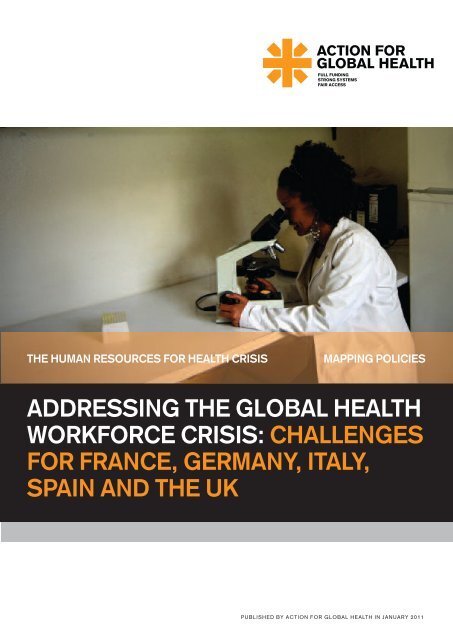

THE HUMAN RESOURCES FOR HEALTH CRISIS<br />

MAPPING POLICIES<br />

ADDRESSING THE GLOBAL HEALTH<br />

WORKFORCE CRISIS: CHALLENGES<br />

FOR FRANCE, GERMANY, ITALY,<br />

SPAIN AND THE UK<br />

PUBLISHED BY ACTION FOR GLOBAL HEALTH IN JANUARY 2011

Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health is a network of<br />

European <strong>health</strong> and development<br />

organisations advocating <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> European<br />

Union and its Member States to play a<br />

stronger role to improve <strong>health</strong> in<br />

development countries. AfGH takes an<br />

integrated approach to <strong>health</strong> and advocates<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> fulfilment of <strong>the</strong> right to <strong>health</strong> <strong>for</strong> all.<br />

One billion people around <strong>the</strong> world do not<br />

have access to any kind of <strong>health</strong> care and we<br />

passionately believe that Europe can do more<br />

to help change this. Europe is <strong>the</strong> world<br />

leader in terms of overall <strong>for</strong>eign aid<br />

spending, but it lags behind in <strong>the</strong> proportion<br />

that goes to <strong>health</strong>.<br />

Our member organisations are a mix of<br />

development and <strong>health</strong> organisations,<br />

including experts on HIV, TB or sexual and<br />

reproductive <strong>health</strong> and rights, but toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

our work is organised around a broad<br />

approach to <strong>health</strong>. AfGH works to recognise<br />

<strong>the</strong> interlinkages of <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> issues and<br />

targets with a focus on three specific needs:<br />

getting more money <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>, making <strong>health</strong><br />

care accessible to those that need it most<br />

and streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>health</strong> systems to make<br />

<strong>the</strong>m better equipped to cope with<br />

<strong>challenges</strong> and respond to peoples’ needs.<br />

Visit our website to learn more about our work and how<br />

to engage in our advocacy and campaign actions.<br />

www.action<strong>for</strong><strong>global</strong><strong>health</strong>.eu<br />

FRONT COVER IMAGE © TERESA S. RÁVINA / FPFE

© TUGELA RIDDLEY/IRIN<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledements<br />

This report was produced by Action <strong>for</strong><br />

Global Health and written by Rebekah<br />

Webb.<br />

Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health would like to thank<br />

<strong>the</strong> many people that contributed to this<br />

report including government officials in<br />

France, Germany, Italy, Spain and <strong>the</strong> UK,<br />

national institutions governing <strong>health</strong><br />

personnel, NGOs and <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> workers<br />

who agreed to be interviewed.<br />

A special thank to Amref Italy that allowed<br />

AfGH Italy to use <strong>the</strong> preview outcomes of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir monitoring report “Personale sanitario<br />

per tutti, e tutti per il personale sanitario!<br />

Executive Summary 4<br />

1. Introduction 5<br />

2. European Union Commitments to<br />

Human Resource <strong>for</strong> Health (HRH) 8<br />

3. How do Member State development<br />

policies address <strong>the</strong> HRH <strong>crisis</strong> in <strong>the</strong><br />

developing world 10<br />

- France 11<br />

- Germany 12<br />

- Italy 13<br />

- Spain 14<br />

- The UK 15<br />

4. Case Studies:<br />

- Madagascar: acute shortages of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers in rural areas 18<br />

- El Salvador: plenty of doctors, yet still<br />

on <strong>the</strong> critical list 20<br />

5. Going Beyond <strong>the</strong> Code: Next Steps 22<br />

6. Are Member State domestic <strong>health</strong><br />

policies <strong>addressing</strong> <strong>the</strong> HRH <strong>crisis</strong><br />

- France 26<br />

- Germany 28<br />

- Italy 30<br />

- Spain 32<br />

- The UK 34<br />

7. Recommendations 36<br />

Bibliography 38<br />

List of Acronyms 38<br />

3

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

In 2006, <strong>the</strong> World Health Organisation (WHO)<br />

estimated that 57 countries, 36 of <strong>the</strong>m in<br />

Africa, were facing a severe shortage of<br />

adequately trained and supported <strong>health</strong><br />

personnel. The international, and in some cases<br />

targeted, recruitment of <strong>health</strong> care workers<br />

from countries that need <strong>the</strong>m most is one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> major driving <strong>for</strong>ces behind this <strong>crisis</strong>.<br />

On 21 May 2010, <strong>the</strong> 63rd World Health<br />

Assembly took <strong>the</strong> long-awaited step of<br />

adopting a new WHO Global Code of Practice<br />

on <strong>the</strong> International Recruitment of Health<br />

Personnel. Ministers of Health agreed to stop<br />

recruiting <strong>health</strong> workers from developing<br />

countries unless agreements are in place to<br />

protect <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong>, and to provide<br />

technical and financial assistance to <strong>the</strong>se<br />

countries as <strong>the</strong>y streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>health</strong><br />

systems. Even a complete implementation of<br />

<strong>the</strong> WHO code, however, is unlikely to<br />

completely stem ‘brain drain’ in <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

sector, nor provide and retain sufficient<br />

numbers of trained staff, particularly if o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

factors beyond <strong>the</strong> code are left unaddressed.<br />

This report compares <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>eign and domestic<br />

policies regarding <strong>health</strong> workers in <strong>the</strong> five EU<br />

countries home to <strong>the</strong> Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health<br />

(AfGH) network, which have some of <strong>the</strong><br />

highest densities of doctors and nurses in <strong>the</strong><br />

world. It looks at <strong>the</strong> reasons <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

shortages in both source and destination<br />

countries, exploring what needs to change or to<br />

be put into practice in order to fulfil <strong>the</strong><br />

requirements of <strong>the</strong> WHO Code of Practice and<br />

to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>health</strong> systems in <strong>the</strong> developing<br />

world. Two countries on <strong>the</strong> list of countries<br />

below <strong>the</strong> minimum density of <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals recommended by WHO, El<br />

Salvador and Madagascar, are included to show<br />

how a chronic lack of investment in <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

sector has resulted in both high unemployment<br />

rates among newly qualified doctors, and <strong>the</strong><br />

poor paying <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> care of <strong>the</strong> rich.<br />

AfGH calls <strong>for</strong> European Member States to take<br />

immediate action to simultaneously tackle <strong>the</strong><br />

push and pull factors driving <strong>the</strong> international<br />

migration of <strong>health</strong> personnel, starting with full<br />

implementation of <strong>the</strong> WHO Global Code of<br />

Practice and <strong>the</strong> EU Programme <strong>for</strong> Action on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Critical Shortage of Health Workers. EU<br />

Member States must fully fund <strong>health</strong> systems<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>ning, ensuring that 25 % of all <strong>health</strong><br />

ODA is allocated to national <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong><br />

strategies and to reaching <strong>the</strong> target of an<br />

additional 3.5 million new <strong>health</strong> workers by<br />

2015. The full set of recommendations is given<br />

at <strong>the</strong> end of this report.<br />

4

© LYNN MAUNG/IRIN<br />

01 INTRODUCTION<br />

On 21 May 2010, <strong>the</strong> 63rd World Health Assembly (WHA)<br />

took <strong>the</strong> long awaited step of adopting a new WHO Global<br />

Code of Practice on <strong>the</strong> International Recruitment of Health<br />

Personnel, six years after <strong>the</strong> idea was first proposed.<br />

Ministers of Health agreed to stop recruiting <strong>health</strong> workers<br />

from developing countries unless agreements are in place to<br />

protect <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong>, and to provide technical and<br />

financial assistance to <strong>the</strong>se countries as <strong>the</strong>y streng<strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>health</strong> systems.<br />

This Global Code of Practice is long overdue. Current<br />

unregulated large-scale migration is having a devastating<br />

impact on <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> systems of source countries – many of<br />

which are struggling to meet <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> Millennium<br />

Development Goals (MDGs). In 2006, WHO estimated that<br />

57 countries, 36 of <strong>the</strong>m in Africa, were facing a severe<br />

shortage of adequately trained and supported <strong>health</strong><br />

personnel 1 . The international, and in some cases targeted,<br />

recruitment of <strong>health</strong> care workers from countries that need<br />

<strong>the</strong>m most is one of <strong>the</strong> major driving <strong>for</strong>ces behind this<br />

<strong>crisis</strong>.<br />

In what has been described as a <strong>global</strong> ‘tug of war’,<br />

countries all over <strong>the</strong> world are seeking to solve <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>health</strong><br />

worker shortages by recruiting from overseas, while <strong>health</strong><br />

workers, increasingly women, are seeking to improve <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

situation by means of migration.<br />

Globally, an extra 4.3 million <strong>health</strong> workers are needed to<br />

make essential <strong>health</strong> care accessible to all 2 . Whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

wealthy or poor, most countries in <strong>the</strong> world are facing<br />

increasing demands on <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>health</strong> systems and yet offer<br />

unattractive working conditions to <strong>health</strong> professionals.<br />

As a result, British midwives travel to Australia, Zimbabwean<br />

doctors transfer to South Africa, Senegalese nurses<br />

relocate to France and German doctors migrate to<br />

Switzerland. Even in <strong>the</strong> face of <strong>the</strong>ir own shortages in rural<br />

and underserved areas, countries such as India and <strong>the</strong><br />

Philippines continue to send trained nurses abroad.<br />

A tiger without teeth<br />

The Code of Practice is <strong>the</strong> first major international<br />

recognition of <strong>the</strong> truly <strong>global</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> worker<br />

shortage and <strong>the</strong> role that unregulated migration is playing in<br />

undermining <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> MDGs. The Code sets out guiding<br />

principles and voluntary international standards <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ethical recruitment of <strong>health</strong> workers, to increase <strong>the</strong><br />

consistency of national policies and prevent unethical<br />

practices. It discourages states from actively recruiting<br />

<strong>health</strong> personnel from developing countries that face critical<br />

shortages and encourages <strong>the</strong>m to facilitate <strong>the</strong> “circular<br />

migration of <strong>health</strong> personnel” to maximise skills and<br />

knowledge sharing when <strong>health</strong> care professionals return to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir home nations after time abroad. Bilateral agreements<br />

between source and destination countries are highlighted<br />

as critical <strong>for</strong> better international coordination of migration.<br />

The Code recognises two different but equal rights – those<br />

of communities to <strong>the</strong> right to <strong>health</strong> and <strong>the</strong> rights of<br />

individuals who seek employment. Prior to <strong>the</strong> Code of<br />

Practice, <strong>the</strong>re was no existing legal and comprehensive<br />

instrument applicable to both sending and receiving<br />

countries.<br />

The Code of Practice promises to have a significant impact<br />

on <strong>the</strong> deplorable shortage of <strong>health</strong> workers in low-income<br />

countries. However, <strong>the</strong> voluntary nature of <strong>the</strong> Code leaves<br />

it vulnerable to dilution or being ignored. To meet <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

MDGs, WHO members will need to respect its provisions<br />

fully. While it is important to respect <strong>the</strong> right of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers to migrate, both developing and developed<br />

countries need to prioritise <strong>health</strong> systems streng<strong>the</strong>ning<br />

and use <strong>the</strong> Code of Practice as a tool to train and retain<br />

<strong>health</strong> workers where <strong>the</strong>re is most need.<br />

Even a complete implementation of <strong>the</strong> WHO Code,<br />

however, is unlikely to completely stem brain drain in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong> sector, nor provide and retain sufficient numbers of<br />

trained staff, particularly if o<strong>the</strong>r factors beyond <strong>the</strong> Code<br />

are left unaddressed. These include <strong>the</strong> role of private<br />

sector actors continuing to recruit from developing<br />

countries and <strong>the</strong> substantial gender dynamics of <strong>the</strong> <strong>crisis</strong>,<br />

given that 80 % of <strong>the</strong> <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> is female 3 .<br />

1 World Health Report, Working Toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong> Health, WHO, 2006.<br />

2 World Health Report, Working Toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong> Health, WHO, 2006.<br />

3 Merchants of Labour, ILO, 2006 and Human Resources <strong>for</strong> Health: A Gender Analysis,<br />

A.George, July 2007.<br />

5

© LYNN MAUNG/IRIN<br />

01 INTRODUCTION<br />

Key points from <strong>the</strong> WHO Code of Practice<br />

International recruitment of <strong>health</strong> personnel should be conducted in accordance with <strong>the</strong> principles of<br />

transparency, fairness and promotion of sustainability of <strong>health</strong> systems in developing countries (art3.5)<br />

Member States should strive to create a sustainable <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> and work towards establishing effective<br />

planning, education and training, and retention strategies that will reduce <strong>the</strong>ir need to recruit migrant <strong>health</strong><br />

personnel (art3.6)<br />

Effective ga<strong>the</strong>ring of national and international data, research and sharing of in<strong>for</strong>mation on international<br />

recruitment are needed to achieve <strong>the</strong> objectives of <strong>the</strong> Code (art3.7)<br />

Member States should facilitate circular migration of <strong>health</strong> personnel, so that skills and knowledge can be<br />

achieved to <strong>the</strong> benefit of both source and destination countries (art3.8)<br />

Destination countries are encouraged to collaborate with source countries to sustain and promote <strong>health</strong> human<br />

resource development and training (art5.1)<br />

Member States should use this Code as a guide when entering into bilateral, regional or multilateral agreements,<br />

to promote international cooperation and coordination on international recruitment (art5.2)<br />

Member States should consider adopting measures to address <strong>the</strong> geographical maldistribution of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers and to support <strong>the</strong>ir retention in underserved areas (art5.7)<br />

Source: European Public Health Alliance (EPHA), 2010.<br />

What is <strong>the</strong> minimum number<br />

of <strong>health</strong> workers required<br />

There is no universal norm or standard <strong>for</strong> a minimum<br />

density or coverage of human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> (HRH) in<br />

any given country or region recommended by <strong>the</strong> WHO.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong> 2006 World Health Report estimated that<br />

countries with a density of fewer than 2.28 doctors, nurses<br />

and midwives per 1,000 people generally fail to achieve a<br />

targeted 80 % coverage <strong>for</strong> skilled birth attendance and<br />

child immunization. There is a direct relationship between<br />

<strong>the</strong> ratio of <strong>health</strong> workers to population and survival of<br />

women during childbirth and children in early infancy. As <strong>the</strong><br />

number of <strong>health</strong> workers declines, survival declines<br />

proportionately.<br />

The map below illustrates <strong>the</strong> huge scale of <strong>the</strong> need in<br />

developing countries. In Africa, <strong>the</strong> density is only 0.8 <strong>health</strong><br />

workers per 1,000 people, compared to 10 per 1,000 in<br />

Europe.<br />

Territory size shows <strong>the</strong> proportion of all physicians<br />

(doctors) that work in that territory.<br />

© Copyright SASI Group (University of Sheffield) and Mark Newman<br />

(University of Michigan).<br />

6

In 2009, <strong>the</strong> High Level Task<strong>for</strong>ce on Innovative International<br />

Financing <strong>for</strong> Health Systems (HLTF) offered two estimates<br />

of <strong>the</strong> number of <strong>health</strong> workers required to achieve <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong>-related MDGs. One, developed by <strong>the</strong> WHO, found<br />

that 3.5 million more <strong>health</strong> workers (including additional<br />

managers and administrators) across 49 low-income<br />

countries were required to accelerate progress towards –<br />

and in many cases to achieve – <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong>-related MDGs,<br />

while also expanding coverage <strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r diseases and<br />

contributing to <strong>the</strong> hunger target in MDG 1. The o<strong>the</strong>r set of<br />

calculations, by <strong>the</strong> World Bank and o<strong>the</strong>r institutions, found<br />

that <strong>the</strong>se 49 countries required 2.6-2.9 million additional<br />

<strong>health</strong> workers – including managers, whose critical role is<br />

too often overlooked.<br />

At present, Europe trains 173,800 doctors a year, Africa<br />

only 5,100. This in itself is a problem that needs to be<br />

addressed. But <strong>the</strong> situation is exacerbated by <strong>the</strong> hiring of<br />

<strong>health</strong> personnel from Africa and o<strong>the</strong>r developing nations to<br />

address staffing shortages in EU Member States. EU<br />

Member States can and must plug <strong>the</strong>ir own staff shortfalls<br />

by <strong>addressing</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own <strong>health</strong> policies, <strong>the</strong>reby putting an<br />

end to <strong>the</strong> 'pull factor' in <strong>health</strong> worker migration from<br />

developing countries. Equally, <strong>the</strong>y must also act to address<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘push factors’ in <strong>crisis</strong> countries, without which <strong>health</strong><br />

workers will continue to seek better opportunities, whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

in <strong>the</strong> EU or elsewhere.<br />

With <strong>the</strong> entry into <strong>for</strong>ce of <strong>the</strong> Lisbon Treaty, <strong>the</strong> eradication<br />

of poverty is <strong>the</strong> main objective of EU development<br />

cooperation and policies. This is more than a noble ambition,<br />

as treaty provisions on development are binding and<br />

en<strong>for</strong>ceable and require a commitment to policy coherence.<br />

This means that EU and Member State policies must<br />

support – or at <strong>the</strong> very least not harm – national, local and<br />

regional ef<strong>for</strong>ts to eradicate poverty in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn partner<br />

countries. The EU must <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e ensure that its policies and<br />

practices on <strong>the</strong> recruitment and retention of <strong>health</strong> workers<br />

do not undermine progress on <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> MDGs.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> world's largest aid donor and one of <strong>the</strong> main<br />

recruiters of <strong>health</strong> workers from developing countries, <strong>the</strong><br />

EU and its Member States have a major responsibility to<br />

ensure <strong>the</strong> Code is respected and not watered down.<br />

European Member States can support this commitment<br />

by allocating 0.1 % of GNI to development <strong>health</strong><br />

spending, 25 % of which should focus on ways of<br />

improving working conditions, pay and training <strong>for</strong><br />

doctors, midwives and nurses in <strong>the</strong> developing world.<br />

About this report<br />

This report compares <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>eign and domestic policies<br />

regarding <strong>health</strong> workers in <strong>the</strong> five EU Member States<br />

home to <strong>the</strong> Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health network, which have<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> highest densities of doctors and nurses in <strong>the</strong><br />

world. It looks at <strong>the</strong> reasons <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> shortages in both<br />

source and destination countries, exploring what needs to<br />

change or to be put into practice in order to fulfil <strong>the</strong><br />

requirements of <strong>the</strong> WHO Code of Practice and to<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>n HRH in <strong>the</strong> developing world. Two countries on<br />

<strong>the</strong> list of countries below <strong>the</strong> minimum density of <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals recommended by <strong>the</strong> WHO, El Salvador and<br />

Madagascar, are included to show how a chronic lack of<br />

investment in <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> sector has resulted in both high<br />

unemployment rates among newly qualified doctors and <strong>the</strong><br />

poor paying <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> care of <strong>the</strong> rich.<br />

7

8<br />

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

02 EUROPEAN UNION COMMITMENTS TO<br />

HUMAN RESOURCES FOR HEALTH (HRH)<br />

“<br />

There is a <strong>global</strong> market <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> workers,<br />

but it is a distorted market, shaped by <strong>global</strong><br />

inequity in <strong>health</strong> care provision and <strong>the</strong><br />

capacity to pay workers, ra<strong>the</strong>r than by <strong>health</strong><br />

needs and <strong>the</strong> burden of disease<br />

EU Strategy <strong>for</strong> Action on <strong>the</strong> Crisis in Human Resources<br />

<strong>for</strong> Health in Developing Countries, 2005<br />

There has been a longstanding understanding in Europe<br />

that <strong>the</strong> shortages of <strong>health</strong>-workers in developing countries<br />

is a critical factor preventing <strong>the</strong> scaling up of service<br />

provision necessary to allow improved <strong>health</strong> care and<br />

improved <strong>health</strong> indicators. At an EU level this awareness<br />

came to <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>e in reaction to <strong>the</strong> epidemics of HIV/AIDS,<br />

Malaria, and Tuberculosis. In 2005 <strong>the</strong> EU adopted a<br />

Programme of Action to combat <strong>the</strong>se poverty diseases<br />

through external action including a separate section devoted<br />

to <strong>addressing</strong> <strong>the</strong> human resource <strong>crisis</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

providers. It was by <strong>the</strong>n clear that <strong>the</strong> lack of <strong>health</strong> workers<br />

in developing countries had reached a critical point and was<br />

a major obstacle to <strong>the</strong> scaling up of services required to<br />

confront not just <strong>the</strong> major infectious diseases but of<br />

achieving all three of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong>-specific MDGs:<br />

“The lack of trained <strong>health</strong> providers undermines ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

to scale up <strong>the</strong> provision of prevention, treatment and<br />

care services. The EU will support a set of innovative<br />

responses to <strong>the</strong> human resource <strong>crisis</strong>. At regional<br />

level, <strong>the</strong> EC will use its support <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> AU and <strong>the</strong> New<br />

Partnership <strong>for</strong> Africa’s Development (NEPAD) to help<br />

ensure strong African leadership in <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mulation and<br />

coordination of a response to <strong>the</strong> human resource <strong>crisis</strong>.<br />

The aim should be to increase incentives <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

workers to remain in or return to developing countries or<br />

regions where <strong>the</strong> need is greatest ra<strong>the</strong>r than to create<br />

barriers to migration.”<br />

- Programme <strong>for</strong> Action on AIDS, TB and Malaria, 2005<br />

”<br />

By <strong>the</strong> end of 2005, <strong>the</strong> European Commission had<br />

adopted a Communication outlining an EU Strategy <strong>for</strong><br />

Action on <strong>the</strong> Crisis in Human Resources <strong>for</strong> Health in<br />

Developing Countries. The actions proposed in <strong>the</strong> EU<br />

Strategy <strong>for</strong> Action were comprehensive and covered<br />

actions at country, regional and <strong>global</strong> level. At country level,<br />

it called <strong>for</strong> support and financing <strong>for</strong> national human<br />

resource plans and <strong>the</strong> inclusion of HRH issues in Poverty<br />

Reduction Strategies. At regional level, it called <strong>for</strong> greater<br />

leadership from <strong>the</strong> African Union and <strong>the</strong> New Economic<br />

Partnership <strong>for</strong> African Development (NEPAD), as well as an<br />

Inter-Ministerial Conference on Human Resources <strong>for</strong><br />

Health in Africa. Globally, <strong>the</strong> concept of a European Code<br />

of Conduct and circular migration were among <strong>the</strong> main<br />

actions recommended.<br />

Programme <strong>for</strong> Action to tackle <strong>the</strong><br />

shortage of <strong>health</strong> workers in<br />

developing countries<br />

In December 2006 <strong>the</strong> European Commission adopted a<br />

Communication outlining a ‘Programme of Action’, broadly<br />

following <strong>the</strong> previous Communication, but also adding<br />

some important elements, such as more detailed actions to<br />

specific world regions, as well as commitments towards<br />

finance, and monitoring and evaluation. The Programme of<br />

Action also went into greater detail than had previously been<br />

<strong>the</strong> case on <strong>the</strong> links between EU <strong>health</strong>, employment, and<br />

migration policies and <strong>the</strong> human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>crisis</strong><br />

in developing countries. This was reflected in <strong>the</strong> priorities<br />

identified by <strong>the</strong> Council of Ministers in <strong>the</strong>ir Council<br />

Conclusions on 14 May 2007 where <strong>the</strong>y highlighted <strong>the</strong><br />

need <strong>for</strong>:<br />

8

4 Policy Coherence <strong>for</strong> Development - Establishing <strong>the</strong> policy framework <strong>for</strong> a whole-of<strong>the</strong>-Union<br />

approach COM (2009) 458 adopted 15 September 2009 was accompanied<br />

by a staff working paper. Quote from page 1999.<br />

(http://ec.europa.eu/development/icenter/repository/SWP_PDF_2009_1137_EN.pdf)<br />

5 COM(2007) 630 European Commission White Paper ‘Toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong> Health: A Strategic<br />

Approach <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> EU 2008-2013’ was adopted on 23 October 2007.<br />

6 Ministers meeting on 5-6 December 2007 in <strong>the</strong> Employment, Social Policy, Health and<br />

Consumer Affairs Council of Ministers adopted conclusions<br />

(http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/lsa/97445.pdf<br />

) drafted on 29 November 2007 by <strong>the</strong> Health Permanent Representatives Committee.<br />

(http://register.consilium.europa.eu/pdf/en/07/st15/st15611.en07.pdf).<br />

7 COM(2008) 725 Green Paper on <strong>the</strong> European Work<strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> Health adopted 10<br />

December 2008.<br />

• Developing principles <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> recruitment of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers from developing countries to work in <strong>the</strong> EU;<br />

• An EU code of conduct <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> recruitment of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers;<br />

• Improved in<strong>for</strong>mation systems (especially statistics) on<br />

human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>;<br />

• Expanding medical education and <strong>health</strong> staff training and<br />

supporting regulatory agencies in improving standards<br />

and achieving a balance between demand and supply <strong>for</strong><br />

qualified staff;<br />

• Exploring ways and means to facilitate <strong>the</strong> temporary<br />

migration of <strong>health</strong> workers from developing countries into<br />

<strong>the</strong> EU.<br />

Evidence of any impact on <strong>the</strong> ground of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

commitments has been at best sparse. Indeed, <strong>the</strong> EU<br />

Commission’s own report on Policy Coherence <strong>for</strong><br />

Development some two years after <strong>the</strong>se Council<br />

Conclusions found “little evidence that <strong>the</strong> EU through its<br />

policies has contributed to reducing migration of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers from <strong>the</strong> three African countries to <strong>the</strong> EU so far” 4 .<br />

EU Health Work<strong>for</strong>ce Policies<br />

There has been some recognition of <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> EU<br />

Member States to change <strong>the</strong>ir domestic policies in line with<br />

development policy.<br />

In October 2007, <strong>the</strong> EU Commission adopted a White<br />

Paper entitled ‘Toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong> Health: A Strategic Approach<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> EU 2008-2013’ 5 . This White Paper explicitly<br />

included <strong>the</strong> adoption of <strong>the</strong> Programme of Action when<br />

referring to <strong>the</strong> need to ensure <strong>the</strong> principle that “<strong>health</strong> in all<br />

policies” was attained. The White Paper also highlighted <strong>the</strong><br />

need <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> EU to take a leadership role in <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong>,<br />

particularly so as to achieve <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> related MDGs and<br />

principles of Aid Effectiveness. Half <strong>the</strong> principles of <strong>the</strong><br />

White Paper related to <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> in general and included<br />

specific reference to <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> <strong>crisis</strong>.<br />

The reaction to <strong>the</strong> White Paper by <strong>the</strong> Council of Ministers<br />

endorsed <strong>the</strong> approach and included recognition of:<br />

“<strong>the</strong> need to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> perspectives in EU<br />

external policies, including <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> and <strong>for</strong><br />

tackling issues related to <strong>the</strong> migration of <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals, development aid in <strong>the</strong> field of <strong>health</strong>,<br />

trade in <strong>health</strong> products, and sharing EU <strong>health</strong> values<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>r countries.”<br />

And underlined:<br />

“<strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> effective implementation of <strong>the</strong> Strategy,<br />

based on close and structured dialogue with <strong>the</strong><br />

Member States and civil society as well as on regular<br />

monitoring of <strong>the</strong> progress achieved.” 6 .<br />

Following <strong>the</strong> adoption of <strong>the</strong> EU Health Strategy a<br />

consultation on issues relating to <strong>the</strong> EU Health Work<strong>for</strong>ce<br />

was opened with <strong>the</strong> adoption of a Green Paper. This Green<br />

Paper included <strong>the</strong> problem of <strong>health</strong> sector ‘brain drain’ of<br />

<strong>health</strong> workers migrating from developing countries to <strong>the</strong><br />

EU. The Green Paper was largely descriptive of <strong>the</strong><br />

preceding policy initiatives, but did highlight <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong><br />

both <strong>the</strong> inclusion of measures to combat brain drain issues<br />

in migration policies in general, and <strong>the</strong> need to elaborate a<br />

code of conduct on <strong>the</strong> ethical recruitment of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers:<br />

“The EU has made a commitment to develop a Code of<br />

Conduct <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> ethical recruitment of <strong>health</strong> workers<br />

from non-EU countries and to take o<strong>the</strong>r steps to<br />

minimise <strong>the</strong> negative and maximise <strong>the</strong> positive<br />

impacts on developing countries resulting from <strong>the</strong><br />

immigration of <strong>health</strong> workers to <strong>the</strong> EU. The need to<br />

deliver on <strong>the</strong>se commitments is reiterated in <strong>the</strong><br />

Progress report on <strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> PfA<br />

adopted in September 2008.” 7<br />

The Kampala Declaration and<br />

Agenda <strong>for</strong> Action<br />

In response to growing international concern about <strong>the</strong><br />

impact of <strong>health</strong> migration on <strong>health</strong> service delivery in<br />

developing countries, <strong>the</strong> first ever Global Forum on<br />

Human Resources <strong>for</strong> Health was convened in<br />

Kampala, Uganda in 2008.<br />

The Kampala Declaration and related Agenda <strong>for</strong> Action<br />

called <strong>for</strong> higher commitment by governments and<br />

development partners to human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>,<br />

providing an overarching <strong>global</strong> framework <strong>for</strong> priority<br />

actions to close <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> worker gap within a decade.<br />

The Global Health Work<strong>for</strong>ce Alliance is tasked with<br />

monitoring progress towards implementing <strong>the</strong> Agenda<br />

<strong>for</strong> Action. Hosted by <strong>the</strong> WHO, <strong>the</strong> Alliance is a<br />

partnership of national governments, civil society,<br />

international agencies, finance institutions, researchers,<br />

educators and professional associations dedicated to<br />

identifying, implementing and advocating <strong>for</strong> solutions.<br />

A key focus is <strong>the</strong> development and implementation of<br />

evidence- and needs-based country HRH plans in<br />

Africa, South Asia and Latin America.<br />

9

8<br />

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

03 HOW DO MEMBER STATE DEVELOPMENT POLICIES<br />

ADDRESS THE HRH CRISIS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD<br />

The countries reviewed in this report have all<br />

made strong, vocal commitments to <strong>addressing</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> shortage of <strong>health</strong> workers in <strong>the</strong><br />

developing world in multiple <strong>for</strong>a. As EU<br />

Member States <strong>the</strong>y are all signatories to <strong>the</strong><br />

Programme <strong>for</strong> Action to tackle <strong>the</strong> shortage of<br />

<strong>health</strong> workers in developing countries. All of<br />

<strong>the</strong>m are members of <strong>the</strong> International Health<br />

Partnership and related initiatives (IHP+),<br />

designed to streng<strong>the</strong>n national <strong>health</strong> plans.<br />

All except Spain are members of <strong>the</strong> G8 and <strong>the</strong><br />

Development Ministries of Germany, France and<br />

<strong>the</strong> UK are partners in <strong>the</strong> Global Health<br />

Work<strong>for</strong>ce Alliance. In addition, each has made<br />

specific commitments to <strong>the</strong> importance of<br />

<strong>addressing</strong> HRH in <strong>the</strong>ir official development<br />

policies. However, as <strong>the</strong> following profiles<br />

show, some countries are doing more than<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs in terms of practical initiatives and solid<br />

funding commitments to address <strong>health</strong> worker<br />

shortfalls.<br />

G8 Commitments<br />

In <strong>the</strong>ir role as G8 countries, <strong>the</strong> UK, Germany, France<br />

and Italy have all made successive commitments to<br />

<strong>addressing</strong> <strong>the</strong> critical shortage of <strong>health</strong> workers in<br />

developing countries since <strong>the</strong> Gleneagles summit in<br />

2005.<br />

In 2008 in Toyako, Japan, <strong>the</strong> G8 pledged to “work<br />

towards increasing <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> coverage towards<br />

<strong>the</strong> WHO threshold of 2.3 <strong>health</strong> workers per 1000<br />

people, initially in partnership with <strong>the</strong> African countries<br />

where we are currently engaged and that are<br />

experiencing a critical shortage of <strong>health</strong> workers”. They<br />

also committed to supporting <strong>the</strong> development of<br />

robust <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> plans and establishing specific,<br />

country-led milestones. USD 60 billion was pledged to<br />

fight infectious disease and streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>health</strong> systems<br />

by 2012.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> 2009 G8 summit in L’Aquila, Italy, <strong>the</strong> G8<br />

renewed <strong>the</strong>ir commitment to an integrated approach to<br />

<strong>health</strong>, <strong>the</strong> importance of supporting national <strong>health</strong><br />

systems with universal coverage, promoting <strong>the</strong><br />

principles of Primary Health Care through active<br />

involvement of civil society and finally promoting a multisectoral<br />

approach to <strong>health</strong> that takes into account <strong>the</strong><br />

social determinants of <strong>health</strong>: “It is essential to<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>health</strong> systems through <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong><br />

improvements”.<br />

This year, <strong>the</strong> G8 Muskoka declaration highlighted task<br />

shifting as a way to make better use of scarce <strong>health</strong><br />

workers.<br />

10

FRANCE<br />

In 2009, France surpassed Germany as <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

European donor country. However in terms of commitment<br />

to <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong>, France sits in <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> countries<br />

reviewed in this report, with only 0.041 % of GNI going to<br />

<strong>health</strong> ODA 8 .<br />

France has taken a leading role in recent years in putting<br />

<strong>health</strong> systems streng<strong>the</strong>ning on <strong>the</strong> international agenda,<br />

including during <strong>the</strong> EU presidency in 2008. Streng<strong>the</strong>ning<br />

<strong>health</strong> care systems, especially human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>,<br />

is one of three core pillars of French <strong>for</strong>eign policy on <strong>health</strong><br />

as set out in <strong>the</strong> ‘2007-2012 Global Strategy <strong>for</strong><br />

Cooperation and Development in <strong>the</strong> Health Sector’. The<br />

initial focus of French ef<strong>for</strong>ts in this area was to fund training<br />

programmes in developing countries. However, <strong>the</strong><br />

evaluations of this training policy, including one conducted<br />

at <strong>the</strong> request of <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2000<br />

throughout sub-Saharan Francophone Africa, highlighted<br />

<strong>the</strong> lack of consistency and overall plan of this policy. It also<br />

revealed a very sharp slowdown in scholarship policies and<br />

a decline in fellowship training due to <strong>the</strong> decrease of direct<br />

technical assistance.<br />

In 2009, France published its ‘Strategy <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

streng<strong>the</strong>ning of human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> in developing<br />

countries’. This document sets out France’s future<br />

commitments regarding <strong>the</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>ning of <strong>health</strong> workers<br />

at <strong>the</strong> bilateral and multilateral levels, <strong>the</strong> latter of which<br />

absorbs <strong>the</strong> majority share of French ODA to <strong>health</strong> (69 % in<br />

2009).<br />

In respect to streng<strong>the</strong>ning HRH, France supports 20<br />

countries, mostly from Sub-Saharan Africa, with about 30<br />

projects ei<strong>the</strong>r entirely dedicated to human resources <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong> or including a HRH component. The main focus of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se projects is training staff, building and furnishing <strong>health</strong><br />

facilities and financing <strong>the</strong> production and implementation of<br />

national plans <strong>for</strong> HRH development. Some projects focus<br />

on <strong>the</strong> ‘retention’ of <strong>health</strong> workers, helping <strong>health</strong> staff to<br />

remain in <strong>the</strong> areas where <strong>the</strong>y work, by providing <strong>the</strong>m with<br />

housing, a motorbike or with computers, desks and medical<br />

equipment. In addition, France launched a hospital twinning<br />

programme, ‘ESTHER’, which links hospitals in France with<br />

<strong>health</strong> facilities in Africa, in order to provide comprehensive<br />

and quality care <strong>for</strong> people living with HIV/AIDS and related<br />

diseases. Among o<strong>the</strong>r activities, ESTHER includes <strong>the</strong><br />

training of <strong>health</strong> professionals in 18 developing countries.<br />

France has signed nine bilateral agreements on migration<br />

flows with countries in Francophone Africa to date. Some of<br />

<strong>the</strong> ratified agreements (i.e. Senegal, Benin and Congo)<br />

address <strong>the</strong> issue of migration with a comprehensive<br />

approach and a particular focus on <strong>health</strong> professionals and<br />

support <strong>for</strong> HRH development 9 . In addition, France seconds<br />

an expert to <strong>the</strong> WHO in Geneva to work as <strong>the</strong> Coordinator<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Health Work<strong>for</strong>ce Migration and Retention<br />

Programme 10 . The French government has also ratified <strong>the</strong><br />

WHO Code of Practice.<br />

8 Source: 2010 Reality Check, Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health 2010. Figures refer to 2008.<br />

9 Innovations in Cooperation. A guidebook on bilateral agreements to address <strong>health</strong><br />

workers migration, I. Dhillon, M. Clarck, R. Kapp, May 2010, ed. by Realizing Rights &<br />

Aspen Institute.<br />

10 Muskoka Accountability Report, Annex 5, G8, 2010.<br />

11 9

8<br />

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

03 HOW DO MEMBER STATE DEVELOPMENT POLICIES<br />

ADDRESS THE HRH CRISIS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD<br />

GERMANY<br />

Germany is one of <strong>the</strong> largest European donors to overseas<br />

development, allocating just over USD 1 billion to <strong>global</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong> in 2008. However Germany has some way to go to<br />

reach <strong>the</strong> 0.1 % of GNI target, ranking only just above Italy<br />

with 0.03 % 11 .<br />

On <strong>the</strong> positive side, <strong>health</strong> systems streng<strong>the</strong>ning (HSS) is<br />

a strategic priority in German development cooperation on<br />

<strong>health</strong>, with emphasis on <strong>health</strong> sector re<strong>for</strong>m and building<br />

<strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> capacity 12 . In particular, <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> sector strategy<br />

positions ef<strong>for</strong>ts to streng<strong>the</strong>n human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong><br />

(HRH) as an integral part of Germany’s HSS strategy and<br />

<strong>the</strong>se aspects are integrated into <strong>the</strong> overall<br />

macroeconomic and <strong>health</strong> sector framework along four<br />

dimensions: policy, management, <strong>the</strong> labour market and<br />

education. A discussion paper on <strong>the</strong> HRH <strong>crisis</strong> was<br />

published in 2010 13 .<br />

Germany’s Ministry <strong>for</strong> Economic Cooperation and<br />

Development (BMZ) does not calculate <strong>the</strong> resources<br />

provided specifically on HRH. It has been estimated that a<br />

range of 25-50 % of funds provided <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> systems<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>ning can be attributed to capacity building, which<br />

amounts to between USD 15.6 and USD 31.25 million in<br />

2009 14 .<br />

Meanwhile, <strong>the</strong> German technical development agency, <strong>the</strong><br />

Deutsche Gesellschaft für technische Zusammenarbeit<br />

(GTZ) supports partner countries in <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>for</strong>mulation of<br />

<strong>health</strong>-policy strategies and staff development plans. It<br />

advises on adapting legal frameworks and works towards<br />

increasing <strong>the</strong> management, administrative and planning<br />

capacities of <strong>health</strong> workers and <strong>health</strong> personnel. O<strong>the</strong>r<br />

priorities of German HSS activities are <strong>the</strong> decentralization<br />

of <strong>health</strong> services and <strong>the</strong> development of social security<br />

instruments, and <strong>the</strong> improvement of <strong>health</strong> infrastructure.<br />

German engagement <strong>for</strong> human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> is<br />

integrated in its broader <strong>health</strong> programmes; HRH support<br />

is implemented both through projects and sector budget<br />

support. Both instruments are integrated into existing<br />

coordination structures, such as sector-wide approaches<br />

(SWAps), where Germany prioritises human resource<br />

management and planning.<br />

Germany is directly involved in <strong>health</strong> sector re<strong>for</strong>m<br />

processes in 16 countries (Bangladesh, Cambodia,<br />

Cameroon, Indonesia, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, Nepal,<br />

Pakistan, Rwanda, South Africa, Tajikistan, Tanzania,<br />

Ukraine, Uzbekistan and Vietnam). In addition, <strong>the</strong>re are two<br />

regional programmes, one in <strong>the</strong> Caribbean (Dominican<br />

Republic, Haiti and Cuba) and one in West Africa (Ivory<br />

Coast Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia). Some country<br />

programmes deal with HRH as a cross-cutting issue while<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs are implementing special programme components.<br />

These <strong>health</strong> worker programme components include preand<br />

in-service training by universities and o<strong>the</strong>r training<br />

institutions, <strong>the</strong> development of E-learning curricula and<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation systems, development of quality assurance and<br />

standards, <strong>the</strong> creation of monetary and non-monetary<br />

incentives to place and retain <strong>health</strong> workers, sector<br />

financing, private service provision and community based<br />

services improve HRH especially in rural and remote areas.<br />

In addition, reintegration support is offered to professionals<br />

who have trained in Germany when <strong>the</strong>y return to <strong>the</strong>ir home<br />

country.<br />

12<br />

11 Source: 2010 Reality Check, Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health 2010. Figures refer to 2008.<br />

12 Germany’s <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> strategy is defined in its <strong>health</strong> sector strategy: Federal<br />

Ministry <strong>for</strong> Economic Cooperation and Development 2009. Sector Strategy: German<br />

Development Policy in <strong>the</strong> Health Sector. Available at:<br />

http://www.bmz.de/en/publications/type_of_publication/strategies/konzept187.pdf<br />

13 BMZ (2009): Ansätze und Instrumente der deutschen Entwicklungspolitik im Bereich<br />

Fachkräftemangel im Gesundheitswesen. Diskussionspapier des Thementeams<br />

Gesundheitssystementwicklung.<br />

14 CRS code 12110, gross disbursements in constant 2008 USD. Estimate made by key<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mant.

ITALY<br />

Health is one of six priority areas in official Italian<br />

development policy 15 . In 2008, Italy committed USD 558.9<br />

million to <strong>health</strong> ODA. Of all <strong>the</strong> countries in this review, Italy<br />

has fur<strong>the</strong>st to go to reach <strong>the</strong> WHO target of 0.1 % of GNI<br />

to <strong>health</strong> aid, dedicating only a quarter of this amount (0.025<br />

%) in 2008 16 .<br />

In its <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> policies, Italy promotes a horizontal<br />

approach designed to ensure universal access and effective<br />

and efficient <strong>health</strong> services. Between 2005 and 2009, Italy<br />

claims to have made a bilateral contribution of USD 12.45<br />

million to HRH 17 . Italy also purports to be actively supporting<br />

<strong>health</strong> systems streng<strong>the</strong>ning and human resources <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong> by means of its contributions to multilateral<br />

organisations such as <strong>the</strong> Global Fund, <strong>the</strong> WHO, UNAIDS<br />

and UNFPA, which toge<strong>the</strong>r receive <strong>the</strong> bulk of Italian<br />

development funds, and by means of its involvement in <strong>the</strong><br />

International Health Partnership and related initiatives 18 . In<br />

practice <strong>the</strong> share of funding devoted to <strong>health</strong> system<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>ning in multilateral organisations is quite variable.<br />

Italy’s 2009 Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Cooperation in Global Health call<br />

<strong>for</strong> “a level of human resources which are adequate both in<br />

qualitative and quantitative terms referring to <strong>the</strong> public<br />

<strong>health</strong> system needs” 19 . According to this framework,<br />

human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> should have:<br />

- Effective systems of training and on-going education<br />

based on experience and best practices, which should be<br />

taught using active learning;<br />

- Salary, working conditions and adequate incentives,<br />

which can thwart <strong>the</strong> unequal geographical distribution,<br />

<strong>the</strong> mobility to <strong>the</strong> private sector, to <strong>the</strong> urban areas and to<br />

<strong>for</strong>eign countries, also through <strong>the</strong> promotion of <strong>the</strong><br />

adoption of international codes aimed to regulate <strong>the</strong><br />

migration of human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong>;<br />

- Adequate professional improvement, supervision and<br />

motivation.<br />

The Guidelines also call <strong>for</strong> support, training and incentives<br />

to increase <strong>the</strong> numbers of community <strong>health</strong> workers. Such<br />

<strong>health</strong> workers are to be integrated into <strong>the</strong> national <strong>health</strong><br />

system and programmes must fit with <strong>the</strong> local cultural<br />

context, in particular regarding reproductive <strong>health</strong>,<br />

maternal, neonatal and child <strong>health</strong>, as well as <strong>the</strong> control of<br />

communicable and non communicable diseases.<br />

In November 2010, Italy signed a major partnership<br />

agreement with Ethiopia to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> system<br />

with EUR 8.2 million. The aim of <strong>the</strong> support is to increase<br />

<strong>the</strong> coverage and quality of <strong>health</strong> services and also to boost<br />

<strong>the</strong> capacity to generate and use strategic in<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

Some 35 % of <strong>the</strong> contribution was allocated directly to <strong>the</strong><br />

Federal Ministry of Health as <strong>health</strong> budget support <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

MDG Fund. The Italian Development Agency has also<br />

promoted South-South cooperation on HRH, such as<br />

support <strong>for</strong> an agreement between Niger and Tunisia,<br />

whereby Tunisia trains <strong>health</strong> professionals from Niger.<br />

15 Source: 2010 Reality Check, Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health 2010.<br />

16 Muskoka Accountability Report Annex 5, p. 40.<br />

17 Promoting Global Health: L’Aquila G8 Health Experts’ Report 2009, pp31-32. Available here:<br />

http://www.g8italia2009.it/static/G8_Allegato/G8%20Health%20Experts%20Report%20and%20Accou<br />

ntability_30%2012%20%202009-%20FINAL%5B1%5D.pdf<br />

18 MAE–DGCS: Salute <strong>global</strong>e: principi guida della cooperazione italiana, July 2009. Available at:<br />

19 http://www.cooperazioneallosviluppo.esteri.it/pdgcs/italiano/LineeGuida/pdf/Principi.Guida_Sanita.pdf<br />

13 9

8<br />

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

03 HOW DO MEMBER STATE DEVELOPMENT POLICIES<br />

ADDRESS THE HRH CRISIS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD<br />

SPAIN<br />

Comparative to its size economically, Spain is a generous<br />

donor to <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> ODA, providing a total of USD 688<br />

million in 2008. Between 2005 and 2008, Spanish <strong>health</strong><br />

ODA increased from EUR 102 to EUR 496 million, with a<br />

tripling of multilateral aid and an increase in bilateral aid from<br />

EUR 130 to EUR 150 million 20 . However, even with <strong>the</strong>se<br />

aid increases, in terms of meeting <strong>the</strong> GNI commitment,<br />

Spain is not even halfway at 0.045 % 21 .<br />

Spanish development policy, including on <strong>health</strong>, is defined<br />

by <strong>the</strong> ‘Master Plan’, a framework approved every four years<br />

by Parliament. The current policy is based on <strong>the</strong> Primary<br />

Health Care approach defined at Alma Ata and highlights<br />

<strong>the</strong> importance of public <strong>health</strong> systems as crucial to <strong>the</strong><br />

attainment of <strong>the</strong> MDGs. The Master Plan 2009-2012<br />

singles out <strong>the</strong> IHP+ as an initiative that can implement aid<br />

effectiveness principles in order to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>health</strong><br />

systems. Of <strong>the</strong> six specific objectives on <strong>health</strong>, two are<br />

directly connected to <strong>addressing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> care worker<br />

shortage: Objective 1 focuses on <strong>the</strong> “<strong>for</strong>mation,<br />

consolidation and sustainability of effective and equitable<br />

<strong>health</strong> systems”, while Objective 2 commits Spain to <strong>the</strong><br />

development of “sufficient and motivated human resources”.<br />

The prominence of <strong>the</strong>se two objectives at <strong>the</strong> beginning of<br />

<strong>the</strong> report reflects <strong>the</strong> importance that Spain allocates to<br />

<strong>the</strong>se issues, at least on paper. However, <strong>the</strong>re is no plan of<br />

action on or any concrete amount of resources allocated to<br />

fulfilling <strong>the</strong>se aims.<br />

The Spanish central administration argues that <strong>health</strong><br />

systems must be rein<strong>for</strong>ced as a package, taking into<br />

account <strong>the</strong> synergies and complex relationship between<br />

<strong>the</strong> different <strong>health</strong> system components and that if one<br />

sector is developed out of proportion with ano<strong>the</strong>r this will<br />

lead to dysfunction (<strong>for</strong> example, too many doctors but no<br />

supplies). Spain regards general budget support to be <strong>the</strong><br />

best tool to fight <strong>the</strong> HRH shortfall and has committed to<br />

allocate 60 % of bilateral aid to <strong>health</strong> system streng<strong>the</strong>ning<br />

under <strong>the</strong> principles of IHP+ by means of direct sector<br />

budget support by 2012. However, since regional<br />

authorities contribute half of Spain’s bilateral aid and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are not committed to IHP+ principles, and <strong>the</strong>re are no<br />

mechanisms to coordinate different stakeholders to fulfil <strong>the</strong><br />

Master Plan, <strong>the</strong> 60 % goal will be extremely hard to reach.<br />

Currently Spain contributes less than 11 % of all bilateral aid<br />

to general budget support.<br />

In addition to increasing funding available <strong>for</strong><br />

comprehensive <strong>health</strong> system streng<strong>the</strong>ning, <strong>the</strong> Spanish<br />

Agency <strong>for</strong> Development Cooperation (AECID) has<br />

developed its first <strong>health</strong> sector plan that includes several<br />

indicators on HRH streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>for</strong> bilateral aid managed<br />

by NGOs and has pledged that by 2013, 80 % of NGO<br />

projects supported will include a component on training<br />

<strong>health</strong> workers.<br />

20 Central Administration Health AID Sectorial Diagnosis, December 2009.<br />

21 Source: 2010 Reality Check, Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health 2010. Figures refer to 2008.<br />

14

UNITED KINGDOM<br />

The UK is <strong>the</strong> leading European donor to <strong>global</strong> <strong>health</strong> 22 . In<br />

2009, <strong>the</strong> British Department <strong>for</strong> International Development<br />

(DFID) allocated 15 % of total ODA, approximately EUR 1.5<br />

billion, to improving <strong>health</strong> in developing countries.<br />

However, this amount still falls short of <strong>the</strong> 0.1 % GNI target<br />

set by <strong>the</strong> WHO, at only 0.058 % of GNI 23 .<br />

The UK is one of <strong>the</strong> few countries with publically available<br />

figures on <strong>the</strong> proportion of <strong>health</strong> ODA allocated to <strong>health</strong><br />

systems, and <strong>the</strong> only country to have completed a voluntary<br />

scorecard on its progress to meet its IHP commitments 24 .<br />

Between 2002/03 and 2008/09, DFID bilateral expenditure<br />

on <strong>health</strong> systems increased from GBP 106 million to GBP<br />

268 million. The share of total bilateral expenditure in <strong>health</strong><br />

allocated to <strong>health</strong> systems increased to 37 % in 2008/09 25 .<br />

Although no exact figures are available, <strong>the</strong> UK claims to be<br />

meeting <strong>the</strong> WHO target of 25 % of <strong>health</strong> aid towards<br />

human resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>ning 26 .<br />

UK funding to <strong>health</strong> systems is channelled through a mixed<br />

funding approach including bilateral programmes, direct<br />

support to national <strong>health</strong> sector plans of partner countries,<br />

and multilateral organisations and <strong>global</strong> funding<br />

instruments such as <strong>the</strong> World Bank, and <strong>the</strong> Global Fund<br />

<strong>for</strong> AIDS, TB and Malaria 27 . Some of <strong>the</strong> activities supported<br />

include <strong>health</strong> staff salaries and retention schemes, preservice<br />

education and training of <strong>health</strong> workers,<br />

enhancement of skills among <strong>health</strong> workers and<br />

productivity as well as management and supervision of<br />

front-line workers.<br />

In Sierra Leone, <strong>the</strong> UK is supporting <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Health<br />

with improved <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> surveillance and strategic<br />

intelligence, including a payroll review, and <strong>the</strong> training of<br />

1,000 new <strong>health</strong> workers to meet <strong>the</strong> increased demand<br />

created by <strong>the</strong> abolition of user fees. DFID has also provided<br />

support to specific <strong>health</strong> worker initiatives, including <strong>the</strong><br />

Royal College of Obstetrician and Gynaecologist training<br />

programmes in five target countries (three in Africa) and <strong>the</strong><br />

training of 12,000 midwives in Pakistan. In Ethiopia, DFID<br />

has awarded GBP 25 million over four years to increase <strong>the</strong><br />

number of community <strong>health</strong> workers tenfold 28 .<br />

DFID and <strong>the</strong> Department of Health jointly support <strong>the</strong> UK<br />

International Health Links Funding Scheme, which provides<br />

grants and support to <strong>health</strong> institutions across <strong>the</strong> UK,<br />

allowing British <strong>health</strong> professionals to streng<strong>the</strong>n and<br />

improve <strong>health</strong> worker capacity of partners in 10 developing<br />

countries in Africa and Asia 29 . The Scheme has given out<br />

over 30 grants to support long-term institutional<br />

partnerships between UK organisations and <strong>the</strong>ir ‘Links’ in<br />

<strong>the</strong> developing world. Building on <strong>the</strong> success of this<br />

scheme, DFID is currently developing a new Health<br />

Systems Partnership Fund to enable UK based <strong>health</strong><br />

workers to support human resources training in developing<br />

countries. The programme will be funded up to GBP 5<br />

million per year and will enable more British <strong>health</strong><br />

professionals to share <strong>the</strong>ir skills with midwives, nurses and<br />

doctors in developing countries through teaching, training<br />

and practical assistance.<br />

22 Euromapping 2010, available at www.euroresources.org<br />

23 Source: 2010 Reality Check, Action <strong>for</strong> Global Health 2010. Figures refer to 2008.<br />

24 IHP scorecard available at: http://network.human-scale.net/groups/united-kingd<br />

25 Health Portfolio Review, DFID 2009, p. 12. Available at:<br />

http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/<strong>health</strong>-portfolio-review-rpt-2009.pdf<br />

26 Muskoka Accountability Report, Annex 5, G8, 2010.<br />

27 DFID PQ response September 2010.<br />

28 Muskoka Accountabiltiy Report, 2010.<br />

29 DFID PQ response Sep 2010. See also http://www.<strong>the</strong>t.org/<strong>the</strong>t-launches-new-international-<strong>health</strong>-linksfunding-scheme<br />

15 9

8<br />

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

03 HOW DO MEMBER STATE DEVELOPMENT POLICIES<br />

ADDRESS THE HRH CRISIS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD<br />

COMPARISON OF THE RELATIVE STRENGTHS AND<br />

WEAKNESSES OF THE FIVE COUNTRIES<br />

COUNTRY<br />

STRENGTHS<br />

WEAKNESSES<br />

FRANCE<br />

Renewal of commitment and leadership<br />

on <strong>health</strong> systems streng<strong>the</strong>ning<br />

ESTHER Twinning Programme<br />

Strong policy commitments are not<br />

translating into funding <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> systems<br />

Failure of HRH training initiatives<br />

GERMANY<br />

Support <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> sector re<strong>for</strong>m in 16<br />

developing countries<br />

Strong policy commitments are not<br />

translating into funding <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> systems<br />

Lack of clarity on who will lead<br />

implementation of <strong>the</strong> WHO Code<br />

ITALY<br />

Direct support to <strong>the</strong> MDG fund within <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong> budget of Ethiopia<br />

Renewal of commitment and leadership on<br />

<strong>health</strong> systems streng<strong>the</strong>ning at G8 summit<br />

in 2009<br />

The bulk of Italian ODA goes to vertical funds<br />

Lagging behind o<strong>the</strong>r major donors on <strong>the</strong> 0.7<br />

ODA and 0.1 <strong>health</strong> targets<br />

SPAIN<br />

Strong policy commitment to streng<strong>the</strong>n<br />

public <strong>health</strong> systems (60 % of bilateral aid<br />

via IHP+ by 2012)<br />

The new AECID <strong>health</strong> plan includes several<br />

HRH indicators: 80 % of NGO projects<br />

funded by AECID in 2012 must include HRH<br />

training.<br />

The 60 % goal on <strong>health</strong> system<br />

streng<strong>the</strong>ning is unlikely to be met<br />

Diversity of actors without adequate space <strong>for</strong><br />

suitable coordination, especially between<br />

central and regional administrations<br />

16<br />

UK<br />

Strong pre- and in-service training initiatives<br />

including <strong>the</strong> new Health Systems<br />

Partnership Fund<br />

Relative transparency on progress towards<br />

HRH and HSS goals (e.g. IHP scorecard)<br />

The UK is a major source destination <strong>for</strong><br />

migrant <strong>health</strong> workers: action needs to be<br />

taken to address <strong>the</strong> role of private<br />

recruitment agencies.

The International Health<br />

Partnership and related initiatives<br />

(IHP+)<br />

The International Health Partnership and related<br />

initiatives (IHP+)<br />

The International Health Partnership and related<br />

initiatives (IHP+) was launched in September 2007<br />

with <strong>the</strong> aim of better harmonizing donor funding<br />

commitments, and improving <strong>the</strong> way international<br />

agencies, donors and developing countries work<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r to develop and implement national <strong>health</strong><br />

plans. The core concept is to mobilise donor countries<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r development partners around a single<br />

country-led national <strong>health</strong> plan, guided by <strong>the</strong><br />

principles of <strong>the</strong> Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Accra Agenda <strong>for</strong> Action.<br />

The IHP+ now includes 49 partners, including 24<br />

developing countries. All of <strong>the</strong> five countries profiled in<br />

this report are members of <strong>the</strong> IHP+.<br />

917

8<br />

© LILIANA MARCOS / FPFE<br />

04 CASE STUDIES<br />

MADAGASCAR: ACUTE<br />

SHORTAGES OF HEALTH<br />

WORKERS IN RURAL<br />

AREAS<br />

Coverage of <strong>health</strong> personnel in Madagascar is well below<br />

<strong>the</strong> threshold recommended by <strong>the</strong> WHO (2.3 <strong>health</strong><br />

workers per 1,000 inhabitants) with approximately only 2<br />

doctors and 3 nurses/midwives per 10,000 inhabitants 30 .<br />

As such, <strong>the</strong> country is one of <strong>the</strong> 49 priority countries listed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> WHO as needing greater support to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong>.<br />

The deficit of <strong>health</strong> workers in Madagascar occurs across<br />

<strong>the</strong> whole country. However, <strong>health</strong> coverage is higher in<br />

metropolitan and in urban areas than rural areas. Regional<br />

differences in <strong>the</strong> distribution of <strong>health</strong> human resources are<br />

significant and considerably weaken <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> care system,<br />

compromising <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> of <strong>the</strong> population. Over 40 % of<br />

<strong>the</strong> population live more than 5km away from a <strong>health</strong> facility.<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Health, some 6,000 <strong>health</strong> care<br />

professionals are ‘missing’. At <strong>the</strong> current pace it would take<br />

at least six years to fill <strong>the</strong> number of positions required, not<br />

including replacements <strong>for</strong> retirees and <strong>the</strong> proportion of<br />

new graduates who turn to specialisation. To address this, it<br />

will both be necessary to increase <strong>the</strong> number of <strong>health</strong><br />

workers trained each year, but also to increase <strong>the</strong> number<br />

of positions available.<br />

PHYSICIANS<br />

TOTAL NEEDS<br />

5068<br />

AVAILABILITY<br />

3988<br />

MISSING<br />

1080<br />

The reasons <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> shortage are familiar to most developing<br />

countries. Less than 200 students graduate in general<br />

medicine each year. The quota of graduates cannot be<br />

increased due to <strong>the</strong> limited capacity of hospitals <strong>for</strong><br />

practical training. For budgetary reasons, not all <strong>the</strong>se<br />

trained staff are able to find positions in <strong>the</strong> national <strong>health</strong><br />

system. The exact unemployment rate of <strong>health</strong> personnel is<br />

not known but it is estimated that <strong>the</strong>re are high<br />

unemployment rates among doctors in urban areas. The<br />

ageing of <strong>the</strong> <strong>health</strong> <strong>work<strong>for</strong>ce</strong> (nearly 50 % will retire within<br />

10 years) and limited training capacity are aggravating<br />

factors.<br />

Most doctors in rural areas work seven days a week and<br />

have little or no holidays. Doctors sent out to <strong>the</strong> bush do not<br />

know how long <strong>the</strong>y will stay <strong>the</strong>re and if <strong>the</strong>y will have<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> advancement in <strong>the</strong>ir careers. There is no<br />

salary increase from one year to ano<strong>the</strong>r and staff poorly<br />

paid. Health worker housing is situated far away from <strong>the</strong><br />

clinic and lacks electricity and water. Local schooling is<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r not available or poor in quality. Some of <strong>the</strong> locations<br />

are insecure and it can be dangerous <strong>for</strong> <strong>health</strong> workers to<br />

go out at night, sometimes covering long distances. Older<br />

physicians in particular are seeking more rewarding working<br />