Number 201: APRIL 2011 - Wagner Society of England

Number 201: APRIL 2011 - Wagner Society of England

Number 201: APRIL 2011 - Wagner Society of England

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Number</strong> <strong>201</strong>: April <strong>201</strong>1

INSIDE<br />

<strong>Number</strong> <strong>201</strong>: <strong>APRIL</strong> <strong>201</strong>1<br />

4 Chairman’s Retiring Letter<br />

5 From the Chair-Elect<br />

6 Die Walküre cinema relay from La Scala Milan<br />

10 Parsifal study day with Ian Beresford Gleaves<br />

11 Tannhäuser at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden<br />

16 “Donald McIntyre – Colossus from New Zealand” The Paul Dawson-Bowling<br />

Lecture<br />

17 “Backstage at Bayreuth”: an evening with James Rutherford<br />

18 “Living in Exile”: The Mastersingers Aldeburgh Programme<br />

20 Parsifal at English National Opera<br />

29 Lance Ryan and Christian Thielemann at Bayreuth<br />

30 DVD review: “<strong>Wagner</strong> and Me” by Stephen Fry<br />

33 Book review: “Richard <strong>Wagner</strong> and the Centrality <strong>of</strong> Love” by Barry Emslie<br />

36 Letters<br />

38 Farewell to...<br />

39 <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Contacts<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

The relay from La Scala presented Katie Barnes with “the squalliest and most ill-tuned<br />

bunch <strong>of</strong> Valkyries” she has ever heard, but at the Royal Opera House she found the<br />

voice <strong>of</strong> Christian Gerhaher to be “like a rich silk scarf sliding slowly to the ground”.<br />

(See: Stop Press on page 38) katie_barnes_unicorn@msn.com<br />

Philip Morgan was converted to <strong>Wagner</strong> while listening to Karajan’s Die Meistersinger<br />

on an old set <strong>of</strong> vinyls in 1992. pbmorgan@btopenworld.com<br />

As a schoolboy in 1958 Paul Dawson-Bowling cycled across Europe to Bayreuth to see<br />

Der Ring, Tristan, Die Meistersinger, and Parsifal. paulizdb@talktalk.net<br />

A <strong>Society</strong> member for 37 years, Robert Mitchell is a Yorkshire GP whose interest in<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> was ignited when he attended Götterdämmerung at Covent Garden in 1963.<br />

drrgm@hotmail.co.uk<br />

Chris Argent is Editor <strong>of</strong> the Richard Strauss <strong>Society</strong> Newsletter. He took over his<br />

stepfather’s membership <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> upon his death in 1986 (“he and my<br />

mother drilled me into tolerating <strong>Wagner</strong>”) and has being writing for <strong>Wagner</strong> News ever<br />

since. chris.argent@ntlworld.com<br />

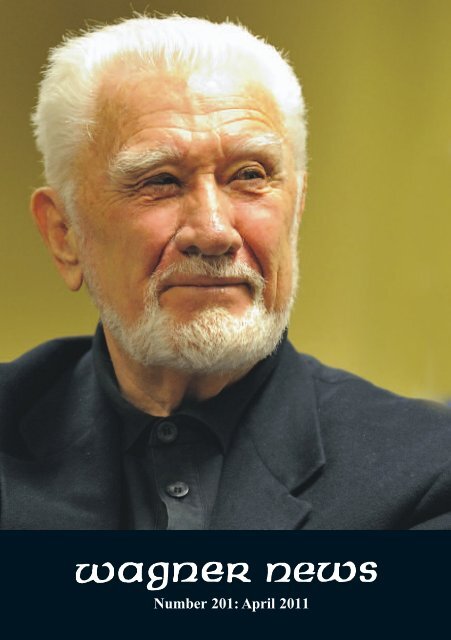

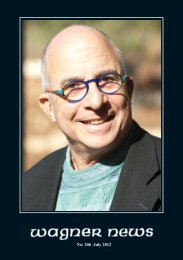

Cover: Sir Donald McIntyre: See report on page 16<br />

Photo: Peter West donningtonart@aol.com 01256 222 339<br />

Designed & Printed by Rap Spiderweb – www.rapspiderweb.com 0161 947 3700<br />

–2–

EDITOR’S NOTE<br />

WRITE FOR WAGNER NEWS!<br />

Editing <strong>Wagner</strong> News is a job to be envied by anyone who would enjoy engaging<br />

with a group <strong>of</strong> very talented and dedicated contributors. We are blessed with volunteer<br />

writers and a photographer who produce work <strong>of</strong> the highest standards for this magazine.<br />

Those who make up this well-established and elite squad are small in number.<br />

Their response to the demands which we make <strong>of</strong> them can <strong>of</strong>ten be described as heroic.<br />

Although this does not compromise the quality <strong>of</strong> their work, excessively exploiting their<br />

goodwill may not be the best way to assure the future development <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> News.<br />

Such expertise can be all too intimidating for readers who might be considering<br />

the idea <strong>of</strong> contributing to this publication themselves. You may also regard the fact that<br />

you have not yet been asked to do so as another inhibiting factor.<br />

Few <strong>of</strong> us could hope to match the experience and ability <strong>of</strong> those upon whose<br />

efforts we have depended year after year. As well as their comprehensive “big” pieces<br />

there is also room for reports and comments from others who may also have something<br />

to tell our readers. To complement the “conventional” material which appears in these<br />

pages ideas and information are also welcome from those who may not have tried their<br />

hand at writing for us before, or who may not have done so for some time.<br />

It’s your <strong>Wagner</strong> News, and so I would be delighted to receive your thoughts. I am<br />

looking for potential writers who can be encouraged to venture forth and join the team.<br />

My knowledge <strong>of</strong> who might be available is necessarily limited, so please don’t wait to<br />

be asked: I enjoy the surprise <strong>of</strong> receiving unsolicited items!<br />

Even very short observations can find a place in the scheme <strong>of</strong> things being put<br />

together for our readers. Pictures are also most welcome as it is simply not possible for<br />

our photographer to turn out for all <strong>of</strong> the events which we cover. We also need pro<strong>of</strong><br />

readers who are able to work via email.<br />

Let’s get down to business and start with the sumptuous programme which<br />

Malcolm Rivers has put together for The Mastersingers weekend in Aldeburgh (see:<br />

centre pages). With no fewer than nine events to cover, I would be very interested to hear<br />

from anyone attending these who might feel able to lend a hand in reporting them for<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> News.<br />

Similarly, our readers deserve to share the impressions <strong>of</strong> those fortunate enough<br />

to see Die Meistersinger at Glyndebourne, Tristan und Isolde at Grange Park, Opera<br />

North’s Das Rheingold or the Hallé’s Die Walküre at the Bridgewater Hall. So please let<br />

me know!<br />

Roger Lee<br />

penmaenmawr@hotmail.com<br />

–3–

THE CHAIRMAN’S RETIRING LETTER TO MEMBERS<br />

Dear Members,<br />

It is now time to move forward with a new <strong>Wagner</strong> News Editor, a new Treasurer,<br />

a new Secretary and a new Chairman.<br />

In a previous letter I explained to you that, now that all the monies were safely<br />

back in the <strong>Society</strong> accounts, it is necessary for me to concentrate on my work for the<br />

Young Artists programmes for both The Mastersingers and the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

We are all very fortunate to be able to call upon our new personnel from within<br />

the strength <strong>of</strong> our membership ranks. I am sure that you will all join me in wishing them<br />

many years <strong>of</strong> successful work on behalf <strong>of</strong> members. All are very adept in their roles,<br />

particularly Jeremy Rowe, whose academic and musical skills allied to a very diplomatic<br />

demeanour will be a great asset to us all.<br />

We have been most fortunate <strong>of</strong> all in these recent times to have had David Waters<br />

in the position <strong>of</strong> Secretary. I can assure you that without his consummate skills and<br />

unceasing energies on our behalf we may still have been in a very sorry state financially.<br />

By following the guidelines <strong>of</strong> the Charity Commission and then <strong>of</strong> the police he ensured<br />

the safety <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

News has just arrived <strong>of</strong> a further bequest to the <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> £11,000. More details<br />

on this will be furnished by our new and excellent Treasurer Mike Morgan.<br />

Before I hand over to Jeremy I can tell you that he and I have had long discussions<br />

on the way forward, and we have planned exciting projects and events for you over the<br />

coming years. What will most notably be maintained are the Live Artists projects such as<br />

the Aldeburgh event, the Rehearsal Orchestra Programme and the Bayreuth Bursary Day.<br />

These will all be in collaboration with The Mastersingers.<br />

The biggest events we are planning are for the May <strong>201</strong>3 Bicentennial<br />

celebrations. The Mastersingers Company will be responsible for providing all <strong>of</strong> the<br />

major projects other than Jeremy Rowe’s Bicentennial Dinner during that year’s special<br />

week as well as events for a full year thereafter. This all culminates in more celebrations<br />

during May <strong>201</strong>4 to close the year. You will not be disappointed.<br />

I hope to see many <strong>of</strong> you at Aldeburgh in May. (See: centre pages.) Do please<br />

approach me with any ideas that you may wish me to propose to the new committee team.<br />

In conclusion I would like to thank you all for your support and loyalty over the<br />

three years <strong>of</strong> my Chairmanship. It was most appreciated.<br />

Malcolm Rivers<br />

malcolmpk@rivers44.fsnet.co.uk<br />

–4–

FROM THE CHAIR-ELECT<br />

There have been a number <strong>of</strong> questions recently about ways in which members <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Society</strong> can communicate with the committee. As Chair-elect, I am clear that I should<br />

be available at any time, and thus you will find my home address, home phone number<br />

and personal e-mail in this edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> News, although work commitments do not<br />

always allow me to respond to messages on the day I receive them.<br />

I am happy for me to be your first point <strong>of</strong> contact with the committee. The<br />

contacts page in this magazine shows other ways <strong>of</strong> contacting other committee members,<br />

usually by email. If you do not have email, please call or write to me first.<br />

Recent resignations have left our committee somewhat depleted, and currently we<br />

are especially anxious to recruit a new Secretary. This is a very busy and important<br />

position to hold on the committee, and suitable only for someone who lives in London,<br />

can attend almost every meeting, and is computer literate, as most <strong>of</strong> the committee<br />

business is conducted electronically. If anyone is interested, please contact me, and we<br />

should meet to discuss the job.<br />

After the excitement <strong>of</strong> the opening night <strong>of</strong> ENO’s Parsifal, we were apprehensive<br />

about going to the opening in Barcelona <strong>of</strong> the Liceu’s new Parsifal only a week later.<br />

Could any other singer match Sir John Tomlinson’s wonderful Gurnemanz? Surprisingly,<br />

the answer was ‘yes’ in the shape <strong>of</strong> Eric Halfvarson, who seemed to us to be very much<br />

in the same mould as Sir John. Christopher Ventris was a strong physical presence on the<br />

stage, and we were much surprised by the ending, when Klingsor (Boaz Daniel)<br />

embraced Titurel (Ante Jerkunica) as the final curtain fell on this post-First World War<br />

production by Claus Guth.<br />

Our recent SGM was extremely well attended, and the capacity crowd remained to<br />

hear James Rutherford’s talk. It reminds us all why the <strong>Society</strong> is important when we hear<br />

a ‘young’ singer like James pay tribute to the assistance he has received from both<br />

Mastersingers and the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

Accounts for 2009 (as seen by members at the meeting on 15th February) will be<br />

sent to all members shortly. I am now able to announce that the Annual General Meeting<br />

will take place on Tuesday 7th June.<br />

Finally may I inform you that I shall be presenting “An evening with Lotte<br />

Lehmann”, featuring her farewell performance, a masterclass, and an interview with her,<br />

on Wednesday 6th July at Portland Place Sixth Form Centre in Great Portland Street: wine<br />

at 7.00pm, presentation at 7.30pm.<br />

Jeremy D Rowe<br />

lyceumschool@aol.com<br />

–5– – 5–

DIE WALKÜRE: “A RICH TAPESTRY OF GLORIOUS SOUND”<br />

Review by Katie Barnes <strong>of</strong> the live relay from La Scala, Milan on 7th December <strong>201</strong>0<br />

I feel that there is always a disadvantage in reviewing a live stage performance on<br />

screen, as I have had to do with this cinema relay. The audience in the theatre can see<br />

everything that the producer has laid before them, and can assess it all for themselves. The<br />

cinema audience is obliged to focus upon the elements which the camera gives them. This<br />

was a particular disadvantage on this occasion, where the cinema version frequently<br />

concentrated upon scenic elements which I, for one, would probably have chosen to ignore<br />

in the theatre.<br />

I lost count <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> times during Act II when the camera was snatched<br />

away from the singers, <strong>of</strong>ten at crucial moments, for lengthy shots <strong>of</strong> the huge, spinning<br />

globe which dominated the stage, upon which various video images were projected in the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> the action (and which made me feel seasick). At other times, the camera dwelt<br />

upon huge video projections (designed by Arjen Klerkx and Kurt D’Haeseleer) which<br />

may have looked splendid onstage, but did not always make much sense on the screen. I<br />

had the impression that many <strong>of</strong> the video effects would have been very confusing to the<br />

audience in the theatre, because they would dwarf the singers and distract attention from<br />

them. It was a pity that some scenes were so dimly lit, to the extent that it was almost<br />

impossible to detect the singers. This was especially unfortunate when Siegmund was in<br />

darkness as he sang his first lines and when he drew Notung from the tree. It was also a<br />

pity that the surtitles appeared to be made up on the spur <strong>of</strong> the moment and were <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

unintentionally risible – Notung was called “Needy”, Fricka ordered Wotan “Hands <strong>of</strong>f<br />

Siegmund”, and Brunnhilde promised Siegmund that in Valhalla he would be welcomed<br />

by “dead heroes in a splendid body”.<br />

Nonetheless, from the cinema relay it was clear that much <strong>of</strong> the production was<br />

very impressive. Hunding’s house in Act I was formed by two large white screens placed<br />

together with a point at the front <strong>of</strong> the stage onto which were projected drawn black and<br />

white images <strong>of</strong> a Victorian room with a cheery golden fire blazing on the hearth. Two<br />

larger screens with images <strong>of</strong> huge, gnarled trees enclosed the house, one with Notung in<br />

its trunk <strong>of</strong>f to one side. Later the projected images varied, and during much <strong>of</strong> the love<br />

scene the screens were blank until, at the beginning <strong>of</strong> Winterstürme, they slowly opened<br />

to reveal a forest made from tall spears. The first appearances <strong>of</strong> Siegmund and Hunding,<br />

both entering with their silhouettes projected upon the screens, were particularly effective,<br />

and later Sieglinde was seen in silhouette, drugging Hunding’s drink.<br />

In an interview shown during the first interval Cassini explained that the first act<br />

was staged in this way because Hunding’s world is two-dimensional: he plays by the rules<br />

but uses them to his advantage. Wotan’s world is also two-dimensional: he has tunnel<br />

vision because he has only one eye. The gods are a dysfunctional family who have<br />

forgotten how to find balance between their emotions, feelings and ideals. Their world<br />

within Valhalla is as claustrophobic as Hunding’s.<br />

The setting for the opening scene <strong>of</strong> Act II was as solid as that for Act I had been<br />

insubstantial. Wotan and Brünnhilde were discovered standing at the foot <strong>of</strong> a massive<br />

statue <strong>of</strong> several rearing horses dominated by the aforementioned spinning globe, with<br />

green lightning flickering all around and green trees projected behind. Later the Wälsungs<br />

fled among a forest <strong>of</strong> standing spears upon which numbers, symbols and tree images<br />

were projected and amid which the final showdown and Siegmund’s death took place.<br />

–6– – 6–

During the Ride <strong>of</strong> the Valkyries the<br />

audience saw a huge slow-motion projection <strong>of</strong><br />

writhing figures including women with long,<br />

flying hair overlaid by the image <strong>of</strong> a rearing<br />

horse. In front <strong>of</strong> the projection screen stood a<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> square pillars <strong>of</strong> various heights<br />

representing the rocks over which the Valkyries<br />

leapt and clambered. Two aerial artists swung<br />

through the air behind the screen. Later the<br />

forest <strong>of</strong> spears returned to create a more<br />

intimate setting for the Wotan/Brünnhilde<br />

scene. The ending gave rise to a most beautiful<br />

visual effect. Brünnhilde was laid to sleep, not<br />

lying supine as usual, but curled up like a kitten<br />

with the long train <strong>of</strong> her dress gathered around<br />

her. During the Magic Fire music the rock upon<br />

which she lay rose to become a substantial<br />

pillar and shaded lamps descended from the<br />

flies to bathe her in red light while more spears,<br />

also glowing red, descended from above to Photo: Teatro alla Scala<br />

fence her in. It was an unforgettable image.<br />

Tim van Steenbergen’s elaborate costumes were generally Victorian in feel. In the<br />

interview Cassini explained that this was because Europe is re-forming itself now in<br />

much the same way as it did in <strong>Wagner</strong>’s time. He also explained that he sees the Ring as<br />

a conflict between natural elements such as the Rheingold and the waters <strong>of</strong> the Rhine,<br />

and those produced by man, such as the metal <strong>of</strong> the sword. Between nature and society<br />

comes virtualisation and we live in a virtual world, hence the extensive use <strong>of</strong> videos. He<br />

indicated that his production is made up <strong>of</strong> musical, visual and dramatic elements which<br />

he gives to the spectator to form a gesamtkunstwerk in their minds. At the end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

interview he appealed to viewers to: “Open up your senses. Look at what is <strong>of</strong>fered to you<br />

and see what it does for you.”<br />

To me this is something <strong>of</strong> a poisoned chalice. While there is something flattering in<br />

crediting the audience with the intelligence to make what they will <strong>of</strong> the production rather<br />

than being told what to think, there is a danger that such a production style can become<br />

merely ‘lazy’, throwing a variety <strong>of</strong> ingredients into the mix without any clear overall plan.<br />

Personally I found some <strong>of</strong> Cassini’s visual elements breathtaking, others distracting, others<br />

plain annoying, and others baffling – which was probably more or less what he intended –<br />

but what I could see on the film suggested that I might have liked it less if I had seen it<br />

onstage. The litmus test for me was how he directed the performers. The cast was a<br />

judicious mix <strong>of</strong> singers who were experienced in their roles and those who were singing<br />

them for the first or second time. Of the newcomers among the leading six, two seemed<br />

uneasy onstage, which suggested to me that they may have been under-directed.<br />

Vitalij Kovaljow (who sang Wotan in trying circumstances with San Francisco<br />

Opera last year) replaced the originally announced René Pape at a late stage. He sang well,<br />

with some truly beautiful tones in the voice in his Act II narrative and in the Farewell, but<br />

he made little <strong>of</strong> the text and did not always convince me that he knew what each word he<br />

sang really meant. Dramatically he was underwhelming. He cut a commanding figure<br />

–7– – 7–

onstage but made little <strong>of</strong> his considerable stature and skulked around mournfully without<br />

exploring the immense depth, complexity, passion, violence, tenderness and tragedy <strong>of</strong><br />

the character. This was a one-note Wotan. He was not helped by a wig which made him<br />

look like an escaped black sheepskin rug.<br />

Photo: Teatro alla Scala<br />

Similarly, Ekaterina Gubanova sang an impressive if hard-voiced Fricka, but<br />

seemed content to stride about the stage pontificating about her rights without appearing<br />

to have the least emotional connection to her erring lord. To be fair, her massive hooped<br />

skirt made physical contact out <strong>of</strong> the question, but when I recalled the intense<br />

relationship which James Rutherford and Magdalen Ashman had conjured up in a concert<br />

environment at the Henry Wood Hall a couple <strong>of</strong> months previously, I felt that the<br />

Rehearsal Orchestra had scored over La Scala.<br />

By contrast Nina Stemme made it impossible to believe that she was singing her<br />

first Brünnhilde and making her house debut. She was already completely inside the<br />

character, breathing and living it to such an extent that she could have been playing it for<br />

years. This was a celestial performance which, like her Isolde at Covent Garden,<br />

completely bowled me over. As with her Isolde, this is a lyric Brünnhilde, more in the<br />

tradition <strong>of</strong> Anne Evans than the powerhouses <strong>of</strong> the past such as Nilsson or Flagstad, and<br />

I suspect that in a large theatre the voice may sound a shade small for the role. But she<br />

sang it with the same fine-spun grace and confidence that she would give to Mozart, and<br />

the creamy-toned voice sounded perfectly focused, as though the slightest sound would<br />

instantly hit the back wall <strong>of</strong> the theatre. Dramatically, as always, she was utterly<br />

compelling, especially in the intensely moving Todesverkundigüng. She even triumphed<br />

over her impossibly ugly costume, a long black ballgown with its train bunched up in an<br />

–8– – 8–

ungainly bustle to reveal black riding boots, with a black greatcoat which, mercifully,<br />

Wotan took from her before their Act III scene. Unfortunately her sister Valkyries were<br />

the squalliest and most ill-tuned bunch I have ever heard, perhaps because the production<br />

required them to risk life and limb leaping around the perilous set swinging their trains<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the way and singing at the same time.<br />

Simon O’Neill as Siegmund was also making his house debut. He created a<br />

positive, likeable character, but sounded vocally patchy all through the performance, and<br />

I later learned that he had been unwell during rehearsals. (At the second performance he<br />

was replaced by the promising Dutch tenor, Frank van Aken). He sounded terrific at first,<br />

especially in his Act I narrative and Ein Schwert verhiess mir der Vater, in which his cries<br />

<strong>of</strong> “Wälse!” made my hair stand on end. But Winterstürme sounded hoarse and unlovely<br />

before he recovered to finish the Act strongly. In his first scenes in Act II he again<br />

sounded uneasy (probably because he had little left to sing and could afford to take a few<br />

risks) before he sang a beautifully lyrical Zauberfest, and his final defiance <strong>of</strong> Hunding<br />

rang clear and true.<br />

Waltraud Meier had also been unwell, and the dress rehearsal had been closed due<br />

to her ill-health. In this performance there was the occasional vocal raw patch and uneven<br />

high note, but for me nothing could dim the pleasure <strong>of</strong> seeing her matchless portrayal at<br />

close quarters. As I observed when reviewing the Royal Opera’s Prom performance in<br />

2005, she is Sieglinde. A downtrodden woman who had almost lost hope blazed into<br />

intense life before our eyes, burning with a rapture so fierce that it seemed almost<br />

impossible to endure. The shining wonder with which she gazed into Siegmund’s eyes<br />

said more for <strong>Wagner</strong>’s creation than any amount <strong>of</strong> complex staging, and amid a<br />

production which would have impoverished the Royal Opera House for six months<br />

nothing meant more than the moment when she cradled the two pieces <strong>of</strong> broken sword<br />

in her arms as though they were the child that she was to bear. For the audience, knowing<br />

that Sieglinde is to die in childbirth, that moment was unspeakably moving.<br />

It cannot be easy for a Wotan to take the stage when John Tomlinson is elsewhere<br />

in the cast. His towering Hunding had all the mighty stature and charisma which<br />

Kovaljow lacked, so that when they met at last it was hard to remember which was meant<br />

to be the god and which the presumptuous mortal, and his voice rang out as arrestingly<br />

as ever. One could tell from his bearing that this Hunding was not merely the local bully<br />

but a man <strong>of</strong> standing, respected in his community, who was entitled to expect assistance<br />

from his friends and neighbours when he had been wronged. But from the instant when<br />

he was seen as a looming shadow behind the screens he exuded menace, and the moment<br />

when he made to strike Sieglinde was terrifying.<br />

But the hero <strong>of</strong> the evening was, <strong>of</strong> course, Daniel Barenboim, presiding over a<br />

Ring 22 years after his legendary collaboration with Harry Kupfer at Bayreuth. He<br />

opened the proceedings with an impassioned speech against Government cuts in arts<br />

funding and followed it with a performance <strong>of</strong> this score, which he knows so well, full <strong>of</strong><br />

depth, passion, urgency, tragedy and ecstasy. He took daring risks with tempi which let<br />

the music breathe but risked letting it drag, yet making his every decision sound right.<br />

The La Scala orchestra played for him as though they were a single person, creating a rich<br />

tapestry <strong>of</strong> glorious sound. It was the music, not the production, which made this<br />

performance unforgettable.<br />

–9– – 9–

STUDY DAY ON PARSIFAL<br />

Report by Philip Morgan<br />

We awaited this day with eager anticipation, and were informed and entertained by<br />

Ian Beresford Gleaves’ presentation on 15th January, timed in anticipation <strong>of</strong> the revival<br />

at the ENO. Members <strong>of</strong> the committee had prepared for a full house in what must have<br />

begun life as an elegant first floor drawing room, now converted into a classroom with<br />

more or less zany posters and photographs on the walls.<br />

Immediately IBG (if I may address him so) got down to the fascinating business<br />

<strong>of</strong> the plan <strong>of</strong> Parsifal with THE KISS in the centre <strong>of</strong> it all, and the implications <strong>of</strong> the<br />

various keys and key relationships which <strong>Wagner</strong> built into his score with such care. A<br />

musical diagram <strong>of</strong> each act was very helpful in showing these, together with the parallels<br />

between Acts I and III, and we began to pick up all sorts <strong>of</strong> new connections as we heard<br />

his expert exposition.<br />

With a Christian background, this reviewer found it interesting that IBG saw so<br />

much Christian theology in the work. Readers will be aware <strong>of</strong> a wide variety <strong>of</strong> views<br />

on this matter. (For example see Mike Ashman in the ENO/ROH Opera Guide for the<br />

contrary view that when the myth came to Wolfram the influence <strong>of</strong> church and state was<br />

beginning to affect the retelling <strong>of</strong> it and therefore the Christian content is entirely<br />

secondary to the main story.)<br />

In view <strong>of</strong> the time available IBG could use illustrations from the opera only<br />

sparingly, but we benefited a great deal from his expertise at the piano in emphasising<br />

themes and chords. We found his list <strong>of</strong> 23 motives – in chronological order – easier to<br />

assimilate than Lionel Friend’s 69 in the Opera Guide. The recording IBG used was<br />

Karajan’s <strong>of</strong> the early 1980s, with Kurt Moll, Peter H<strong>of</strong>fmann and Dunja Vejzovic. Our<br />

thanks to all who made this notable day possible, particularly, <strong>of</strong> course, to Ian Beresford<br />

Gleaves himself.<br />

Photo: David Waters<br />

SIEGFRIED DAY SCHOOL<br />

Broadway, The Cotswolds, 9th July<br />

Ian Beresford-Gleaves will illustrate his examination <strong>of</strong> the musical and<br />

dramatic structures in this work at the piano and from CDs. The day is intended as<br />

preparation for the performances which will take place at Longborough on 25th, 28th<br />

and 30th July.<br />

The venue is Farncombe Estate Centre, Broadway, WR12 7LJ. Tel 01386<br />

854100. www.FarncombeEstate.co.uk. Day School price: £70.<br />

– 10 –

WOLFRAM WAS THE STAR OF THE EVENING<br />

Review by Katie Barnes <strong>of</strong> Tannhäuser at the Royal Opera House,<br />

Covent Garden on 22nd December <strong>201</strong>0<br />

Coincidentally this was the second production in a row at Covent Garden to use<br />

the concept <strong>of</strong> a theatre within a theatre. David McVicar’s brilliant production <strong>of</strong> Adriana<br />

Lecouvreur in November used a beautiful, detailed set inspired by the Markgräfliches<br />

Opernhaus in Bayreuth, beloved <strong>of</strong> generations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> Festival goers. Tim Albery’s<br />

production <strong>of</strong> Tannhäuser takes the Royal Opera House itself as its basis. The link<br />

between the theatre and Tannhäuser is more tenuous than that for Adriana in which an<br />

actress is the heroine and part <strong>of</strong> the action is set backstage.<br />

During the Prelude a pale light spreads over the curtain which then rises to show<br />

the stage in darkness. Gradually we can discern the figure <strong>of</strong> Tannhäuser sitting in a chair<br />

in the down left corner, facing upstage. Elisabeth appears upstage wearing a dark, fulllength<br />

coat over her white dress with a scarf covering her bright hair. She smiles at<br />

Tannhäuser and holds out her hand to him, but he looks away in shame and she bows her<br />

head in despair. A smaller version <strong>of</strong> the Royal Opera House proscenium and curtain are<br />

flown in, concealing her from sight. A few seconds later the curtain rises, showing the<br />

woman in the coat with her back to the audience, but when she turns to face us it is Venus,<br />

who seductively removes the coat and scarf to reveal herself in an <strong>of</strong>f-the-shoulder black<br />

evening dress. (This is a nice touch. If the two roles are not doubled a device like this is<br />

a good way to show Tannhäuser’s confusion between the pure and the pr<strong>of</strong>ane).<br />

She disappears inside the curtains and six dancers, wearing replicas <strong>of</strong> her dress,<br />

emerge. They circle Tannhäuser and lead him inside the curtains. One by one a series <strong>of</strong><br />

young men dressed like him sit in the chair and are lured inside the curtains. On this<br />

showing the Venusberg has as high a success rate as Klingsor’s magic garden in seducing<br />

young knights from the path <strong>of</strong> righteousness.<br />

A long table is pushed out between the curtains and is used as the centrepiece for<br />

the ballet and the subsequent scene between Tannhäuser and Venus. The Venusberg ballet<br />

is always hard to present convincingly. The mythological scenes prescribed by <strong>Wagner</strong><br />

would not be sufficient nowadays to persuade the audience <strong>of</strong> the seductive nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

place, and modern dance does not always seem to me to be appropriate. Members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

audience sitting around me liked the choreography, but to me the dancers’ endless chases<br />

around and across the table, the stripping <strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> clothes and the gyrations conveyed the<br />

depravity <strong>of</strong> the Venusberg without showing us its allure, or why Tannhäuser (or any other<br />

<strong>of</strong> Venus’ captives) would want to stay there.<br />

Venus herself arises from the depths <strong>of</strong> the stage, not in the shell prescribed by<br />

Botticelli, but reclining upon a red velvet chaise-longue. She is well past the first flush<br />

<strong>of</strong> youth, no longer an ageless goddess but a vulnerable, rapacious, increasingly desperate<br />

woman who uses cajolery, scorn and emotional blackmail to try to win her wandering<br />

lover back. I found little allure in what is surely meant to be the most seductive character<br />

in all opera, and there was scant sense <strong>of</strong> the relationship which has kept Tannhäuser in<br />

thrall for so long.<br />

– 11 –

Distractingly during the duet the platform forming the stage-within-a-stage rises<br />

up and down for no easily discernible reason, and when Tannhäuser invokes the Madonna<br />

the inner stage, with Venus and her chaise-longue on it, descends, leaving him on the<br />

forestage. Unfortunately, although she sinks from the view <strong>of</strong> the stalls, the Amphitheatre<br />

can still see the singer creep away. Albery should have spent less time playing with the<br />

stage machinery and taken greater care with his sightlines.<br />

The descent <strong>of</strong> the platform leaves a huge void in the centre <strong>of</strong> the stage, from<br />

which a single green tree arises with the Shepherd Boy sitting beneath it, singing his<br />

song. Unfortunately the sight <strong>of</strong> one tree in the grey and black abyss is not really enough<br />

to convey the intense contrast between the underground, artificial environment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Venusberg which Tannhäuser has just left and the open air, bright sky and fresh, springlike<br />

atmosphere <strong>of</strong> the world above.<br />

The Pilgrims’ voices are heard issuing from the void. Their chorus sounds<br />

incredibly beautiful but the scene has a curiously ghostly air as they pass by unseen<br />

(apparently underground) leaving Tannhäuser alone on the darkened stage the whole<br />

time. The lights go up to reveal the Landgrave and his party standing on the stage behind<br />

the void which highlights Tannhäuser’s moral, artistic and emotional separation from<br />

them. This makes it hard for the singers to project their opening phrases from such a long<br />

way back, and inevitably some sound was lost in the void.<br />

Far from being the noble hunting party described by <strong>Wagner</strong> these are present day<br />

soldiers armed to the teeth who instantly aim their guns at the unknown intruder.<br />

Gradually they come down to join him on the forestage, making him one <strong>of</strong> their group<br />

again even before he decides to return to them. His different relationships with them are<br />

very clearly marked. I particularly noticed his hesitation before clapping Biterolf on the<br />

shoulder. Clearly there has been little love lost between them in times past, and this paves<br />

the way for their clash in Act II.<br />

At the end the group leaves and the inner proscenium and the curtain descends<br />

again. Elisabeth appears from between the curtains, glowing with excitement and<br />

happiness and goes to sit in the chair which Tannhäuser occupied at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Act just as the music ends and the lights go out. The cycle is beginning again, but in the<br />

next Act Tannhäuser will perform and she will be in the audience.<br />

The setting for Act II looks like a war zone. The inner proscenium lies collapsed<br />

and in pieces. The curtain has been reduced to a few torn, discoloured fragments.<br />

Everything is covered in plaster dust and a few misshapen gilt chairs lie scattered about.<br />

The chorus men are all partisans, heavily armed with guns and bullet belts, wearing<br />

overcoats and woolly hats. The women wear dark clothes with long overcoats like<br />

Elisabeth’s with headscarves and they carry candles which they light, passing the flame<br />

from one to another, and set them out in a phalanx at the centre <strong>of</strong> the stage. It looks like<br />

a memorial, as though each candle is for someone who has died in the conflict.<br />

I presume that all this is inspired by the Landgrave’s lines “Wenn unser Schwert<br />

in blutig ernstern Kämpfen/ stritt für des deutschen Reiches Majestät” (If our swords in<br />

battles grim and bloody did battle for the majesty <strong>of</strong> the German realm). It is an effective<br />

– 12 –

way <strong>of</strong> presenting the scene, and shows one more reason why everyone turns against<br />

Tannhäuser when the truth has been revealed. They have been risking their lives in the<br />

struggle for freedom while he has been enjoying a life <strong>of</strong> idleness in the Venusberg.<br />

Elisabeth is like a saint to them. She is the pure beacon for whom they fight – her white<br />

dress stands out amid the dark clothing worn by those around her. They are all terribly<br />

proud <strong>of</strong> her. But she is no saint, but a flesh-and-blood woman, ready to break free <strong>of</strong> the<br />

confines <strong>of</strong> her life.<br />

The civilised song contest between the Minnesängers (who look faintly awkward<br />

in their dinner jackets beneath their overcoats) contrasts oddly with their audience <strong>of</strong><br />

rough fighters who hang eagerly upon every note sung. It underlines the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

culture to this war-torn environment far more than a conventional mediaeval production<br />

could do. But Tannhäuser’s interventions undermine the courtly ritual and violence<br />

begins to surface. Reinmar steps forward to reply to Wolfram’s song, but Tannhäuser<br />

rudely pushes him out <strong>of</strong> the way. Biterolf has to be physically restrained by the other<br />

Minnesängers from attacking Tannhäuser, shakes himself free and grips his skull,<br />

desperate to regain control. When Tannhäuser discloses that he has been in the Venusberg<br />

the men turn upon him savagely, all veneer <strong>of</strong> civilisation gone.<br />

Act III is set in a desolate landscape littered with pieces <strong>of</strong> the fallen proscenium,<br />

now weathered almost beyond recognition. The tree from Act I has been uprooted and lies<br />

leafless and dead at one side <strong>of</strong> the stage. Elisabeth, her coat tattered, her pure white dress<br />

stained and soiled, wanders amid the desolation. The pilgrims cross the stage, slowly<br />

removing their upper garments, presumably to denote their spiritual cleansing, while<br />

Elisabeth searches desperately among them until she collapses, exhausted, in Wolfram’s<br />

arms. During the postlude to her prayer she walks slowly to the back <strong>of</strong> the stage until she<br />

is enveloped in its darkness, a deeply moving moment.<br />

Tannhäuser stumbles in at the back in the wake <strong>of</strong> the rejoicing pilgrims. Both his<br />

confrontation between Wolfram and the Rome Narration are performed very simply with<br />

no distractions whatsoever and are all the better for it. All the more pity then that the<br />

finale is so disappointing. The void yawns and Venus arises from it, reclining on her<br />

chaise-longue to receive Tannhäuser again. The speed with which she then has to<br />

disappear is almost comical. There is no sight <strong>of</strong> Elisabeth’s funeral procession and<br />

Tannhäuser simply wanders out at the back as she had done, while Wolfram staggers<br />

brokenly away at the side. The pilgrims flood onto the stage singing the final chorus and<br />

the Shepherd Boy returns, casts the dead tree aside, plants a sapling and sits in the chair<br />

to watch it during the final chords. This ending carried a message <strong>of</strong> new growth and new<br />

beginnings, but there was little visual sense that Tannhäuser had been redeemed.<br />

This was the first staging <strong>of</strong> Tannhäuser at Covent Garden for 23 years. One<br />

reason for its long absence was undoubtedly the extreme difficulty in casting the arduous<br />

title role which has been shunned by many experienced Siegfrieds and Tristans. Johan<br />

Botha attracted some unkind comments in the national press due to his bulk and<br />

ungainliness. However I felt that Albery treated his giant economy size tenor with great<br />

tact, and constructed a production which took account <strong>of</strong> his physical limitations in a way<br />

– 13 –

which last year’s revival <strong>of</strong> Lohengrin signally failed to do. Botha stayed the course nobly<br />

through his marathon role with only a couple <strong>of</strong> minor vocal blemishes, trumpeting his<br />

calls to love, shading his voice most beautifully in his love scene with Elisabeth and<br />

saving impressive vocal and emotional power for the Rome Narration.<br />

Photo: Clive Barda, The Royal Opera<br />

Elisabeth is frequently played as a bloodless saint, but the ever-remarkable Eva-<br />

Maria Westbroek created the character <strong>of</strong> a vital, passionate woman who is defined by her<br />

love for Tannhäuser and who is destroyed by his betrayal. She blazed across the stage. It<br />

was impossible to take one’s eyes from her, and the urgency and full-bloodedness <strong>of</strong> her<br />

singing endowed the role with a sensuality that it does not usually have. Her acting in Act<br />

III was especially astonishing. In her Prayer, she seemed to be consciously willing herself<br />

to death, like the Chosen Maiden in Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite <strong>of</strong> Spring, and in her final<br />

exit, barely able to stand, she appeared to merge into the darkness as though she were<br />

vanishing up to Heaven before our eyes.<br />

It would be hard for any Venus to win a fight against this Elisabeth for<br />

Tannhäuser’s love and Micaela Shuster did not quite manage it. As I indicated above, the<br />

production portrayed the goddess as an ageing, desperate woman, and Schuster’s hard<br />

voice and presence held little allure. It was a vocally strong performance, but not an<br />

attractive one.<br />

By common consent, the Wolfram was the star <strong>of</strong> the show. The Royal Opera<br />

House scored a coup by engaging the great Lieder singer Christian Gerhaher for his first<br />

operatic appearances in this country. It is very hard to write about such an artist as this,<br />

because he makes everything seem so simple. Art conceals art. His voice is indescribably<br />

beautiful, like listening to a rich silk scarf sliding slowly to the ground. But his artistry<br />

goes beyond a vocal beauty that makes one want to weep. To hear him sing <strong>Wagner</strong>’s<br />

music with every word perfectly nuanced and every note precisely shaded with the care<br />

<strong>of</strong> a master Lieder performer was a revelation, unlike anything I have heard in <strong>Wagner</strong>.<br />

Whatever the rest <strong>of</strong> the performance had been like, it would have been worthwhile to<br />

hear him sing “O du mein holder Abendstern”, five minutes <strong>of</strong> pure operatic heaven.<br />

Dramatically, too, he was remarkable. Wolfram’s timidity in Elisabeth’s presence,<br />

– 14 –

his fatal inability to declare himself to her, his physical gaucheness and self-effacing<br />

modesty were so convincingly portrayed that I thought at first that Gerhaher must be<br />

inexperienced as a stage performer. I only gradually realised that it was simply brilliant<br />

acting from a performer so subtle that he never lets us know that he is acting. The moment<br />

in Act III when Elisabeth refused his request to accompany her and he hugged her<br />

awkwardly in farewell said everything that could never be spoken and was utterly<br />

heartbreaking. One sensed that Wolfram knew that he would have to live on that moment<br />

for the rest <strong>of</strong> his life. I felt privileged to have seen him and can only hope that the Royal<br />

Opera House hires him again sometime.<br />

David Waters has reported that on 18 December Gerhaher was snowbound in<br />

Munich and arrived in time only to sing Act III. In the first two acts a stage director<br />

walked the role <strong>of</strong> Wolfram onstage while Daniel Grice, a Jette Parker Young Artist, sang<br />

from the side <strong>of</strong> the stage. By all accounts he did extremely well, but I have to ask why<br />

the Royal Opera had not ensured that the cover for a major role in a major production was<br />

not sufficiently prepared to be able to sing on stage. Both Grice and the audience were<br />

short-changed.<br />

This vexed question rose again at the performance under review, as Christoph<br />

Fischesser, cast as the Landgrave, was suffering from a throat infection. Once again the<br />

cover, the excellent Andrew Greenan, was obliged to sing from the side while Fischesser<br />

acted. The sense <strong>of</strong> alienation was acute, especially in Act I when Fischesser was standing<br />

well upstage while Greenan’s voice rang out from down right, and was heightened<br />

because Fischesser did not bother to mime the words. If one was not watching Greenan,<br />

and was not familiar with the score, it was hard to tell when the Landgrave was singing.<br />

The Royal Opera really has to do better than this.<br />

There was fine work from the other Minnesängers, especially Timothy Robinson’s<br />

haughty, exquisitely lyrical Walther – I would like to hear him sing David someday – with<br />

strong support from Steven Ebel’s touchingly awkward, enthusiastic Heinrich, Jeremy<br />

White’s genial Reinmar, and Clive Bayley’s edgy, touchy Biterolf, a human powder keg<br />

waiting to explode.<br />

Semyon Bychkov, building on his 2009 triumph here in Lohengrin with the same<br />

tenor, conducted a spacious, majestic, intense account <strong>of</strong> the Paris version <strong>of</strong> this<br />

problematic and much-changed score, drawing superb work from the orchestra and the<br />

hugely augmented chorus. The sound <strong>of</strong> the massed Pilgrims returning from Rome was<br />

truly epic. Yet my abiding memory <strong>of</strong> the evening will be <strong>of</strong> one man singing to a harp<br />

on a darkening stage. Less can be more. The Landgrave may be the ruler, but Wolfram<br />

was King <strong>of</strong> the night.<br />

– 15 –

Paul Dawson-Bowling Annual Lecture 26th January <strong>201</strong>1<br />

DONALD MCINTYRE: COLOSSUS FROM NEW ZEALAND<br />

Report by Jeremy Rowe<br />

A good crowd attended Portland Place Sixth Form Centre to hear Paul Dawson-<br />

Bowling interview Sir Donald McIntyre. Paul and Sir Donald had chosen four extracts<br />

from DVDs <strong>of</strong> Sir Donald’s performances, and these formed the basis <strong>of</strong> Paul’s questions.<br />

First we saw the Dutchman’s opening scene from Sir Donald’s 1975 movie. Filmed<br />

largely in a lake in Germany, Sir Donald had spent much <strong>of</strong> the filming wearing a wet suit<br />

and splashing around in freezing water. Of his performance he commented: “We’re here<br />

not because it’s easy, but because it’s difficult.” He told us that he found the character <strong>of</strong><br />

the Dutchman challenging: “hard to find the core <strong>of</strong> the role.” He had searched and<br />

searched and decided the Dutchman was mad. (He used the German word verrückt.)<br />

He said he was always very interested in the psychology <strong>of</strong> the characters, and<br />

especially with the conflict within a character. He felt <strong>Wagner</strong> developed this more and<br />

more over time, and this notion <strong>of</strong> inner conflict had reached its zenith with Parsifal and<br />

Hans Sachs. In preparing a role Sir Donald looked for the two sides <strong>of</strong> each character. In<br />

doing so he had been strongly influenced by Klemperer, who encouraged him to seek the<br />

“Fundament”, the guts <strong>of</strong> the performance.<br />

The second DVD extract was Wotan’s Act II monologue from Chereau’s 1976 Ring<br />

at Bayreuth. Sir Donald continued his theme <strong>of</strong> seeking the core <strong>of</strong> a character, quoting<br />

Glen Byam Shaw’s instruction to “look for the truth <strong>of</strong> a performance”. He paid tribute<br />

to what he had learned from the “great team <strong>of</strong> coaching experts” at Covent Garden,<br />

especially Reggie Goodall who had given him “hours and hours and hours”.<br />

He told us how he had liked working with Chereau, who at only 27 had a new view<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Ring, and brought a pedagogic approach to the staging. Constantly asking<br />

questions, he would continuously try different moves within each scene, forcing much<br />

rethinking <strong>of</strong> the characterisations.<br />

The final extracts were shorter, and both from Meistersinger. First we saw<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the 1988 production from Sydney, then some <strong>of</strong> the 1984 production from<br />

Zurich. Sir Donald noted that the role <strong>of</strong> Hans Sachs is the most demanding <strong>of</strong> all<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong>’s leading men – more to sing in one evening, than the whole <strong>of</strong> the Wotan part in<br />

the Ring.<br />

Sir Donald concluded by saying, “This job I’ve had ..... I cannot think <strong>of</strong> anything<br />

I’d rather have done. It’s been just a thrill from beginning to end!”<br />

Peter West, donningtonart@aol.com<br />

– 16 –

“BEHIND THE SCENES AT BAYREUTH”<br />

AN EVENING WITH JAMES RUTHERFORD<br />

Report by Katie Barnes<br />

It was a joy to welcome James Rutherford on 15th February to hear him talk to<br />

Jeremy Rowe. He thanked the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> for their support in giving him his first<br />

chance to sing the role <strong>of</strong> Hans Sachs, without which he would not have sung it at<br />

Bayreuth.<br />

After his success at the Seattle International <strong>Wagner</strong> Competition in 2007 Oper<br />

Graz approached him to <strong>of</strong>fer him Sachs, and Malcolm Rivers gave him the opportunity<br />

to sing Act III Scene 1 with orchestra before he learned the rest <strong>of</strong> the score. His life<br />

changed after the first night in Graz in September 2009 because it gained him so much<br />

attention from European opera managements.<br />

In January <strong>201</strong>0 he was invited to audition for Katharina <strong>Wagner</strong>, who told him<br />

that he was on “a short list <strong>of</strong> one” to replace Alan Titus as Sachs at Bayreuth. She wanted<br />

a young singer who would be part <strong>of</strong> the ensemble rather than a ready-made star. He was<br />

the only new member <strong>of</strong> the cast, and rehearsals began only 13 days before the first night.<br />

Asked how much he was required to understand Katharina’s vision, he admitted<br />

that the production looked unconventional, but that “when you’re on the inside, it’s<br />

completely different”. Katharina has a showy side, but she also has tremendous integrity.<br />

She makes a point <strong>of</strong> taking a bow after every performance so that the audience can boo<br />

her!<br />

He has now sung Sachs 16 times and feels that the role fits him like a glove. He<br />

will sing his first Holländer in Hamburg next year (he understudied Bryn Terfel at Covent<br />

Garden in 2009) and is looking at Wotan, but he has rejected <strong>of</strong>fers to sing it in concert<br />

in <strong>201</strong>3, feeling that the role does not fit his voice so well as Sachs, and that he is not yet<br />

ready for it. He is a regular guest at Graz, where he is currently singing Germont, and will<br />

sing Iago and Orest there later this year. He ended by expressing regret that British<br />

singers are so <strong>of</strong>ten unable to find employment in Britain and that financial constraints<br />

mean that our companies can mount so few productions. In Graz money is no object.<br />

Photo: Peter West donningtonart@aol.com<br />

– 17 –

– 18 –

– 19 –

THE WAY TO THE GRAIL<br />

Parsifal at English National Opera on 16th, 19th and 24th February <strong>201</strong>1<br />

Review by KATIE BARNES<br />

On its first showing in 1999 Nicklaus Lehnh<strong>of</strong>f’s production was criticised for its<br />

ugliness, yet I recall Philippe Monnet reviewing it in <strong>Wagner</strong> News and praising it for its<br />

beauty. This Monsalvat is T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land, terribly bare and bleak. Despite the<br />

abundant references to nature in the text, all we see on the stage are grim whites and greys,<br />

unrelieved by so much as a blade <strong>of</strong> grass. The theft <strong>of</strong> the spear has caused the Grail’s<br />

domain to decay to the point <strong>of</strong> total ruin.<br />

In the first scene only the front half <strong>of</strong> the stage is visible. A section <strong>of</strong> the flooring is<br />

raised, revealing a trap filled with stones and at the left is a chute with a pile <strong>of</strong> stones at its<br />

foot. The floor is scattered with small stones and a couple <strong>of</strong> chairs stand at odd angles. The<br />

back wall is peppered with bullet holes and studded with nails. The harsh white lighting falls<br />

across the stage at an angle, making the nails cast long shadows and throwing huge,<br />

intimidating shadows <strong>of</strong> the singers onto the back wall. A gigantic stone protrudes through a<br />

huge, irregular hole in the back wall. It is the barrier which keeps all comers from<br />

approaching the Grail unbidden. As the Squires intone the prophecy “Made wise through<br />

pity, the purest fool” the stone moves backwards a little, creating a space through which<br />

Parsifal climbs, clutching his bow and arrow.<br />

Gurnemanz, Amfortas and all the Knights and Squires wear grey, with very pale,<br />

grey-white makeup. Their costumes recall those <strong>of</strong> the Terracotta Army, with the Squires in<br />

three-quarter length coats and pantaloons, the Knights in long, loose robes and skull caps (the<br />

two solo Knights have coats fastened at one shoulder in Chinese fashion), and Gurnemanz,<br />

his hair drawn back in a bun, in a massive overcoat with a huge, turned-over collar and central<br />

fastening. The Chinese influence in the costumes recalls how <strong>Wagner</strong>’s interest in Buddhism<br />

influenced the creation <strong>of</strong> the opera. Amfortas also wears a long robe with a golden crown,<br />

and his upper body is bound in layers <strong>of</strong> ragged grey bandages. The whole effect is as though<br />

the members <strong>of</strong> the Grail community have become dehumanised and are slowly turning to<br />

stone. With the exception <strong>of</strong> Gurnemanz, they are certainly hard-hearted: the Knights and<br />

Squires shrink from Kundry in terror when he is watching, but when his back is turned the<br />

Third and Fourth Squires are menacing thugs who torment her mercilessly and later menace<br />

Parsifal.<br />

Parsifal and Kundry by contrast are both children <strong>of</strong> nature who wear rich russets and<br />

browns. Kundry’s costume is especially effective: a long, close-fitting squirrel-red garment,<br />

cream at the front, made <strong>of</strong> rough fabric which could be taken to resemble either fur or<br />

feathers. Her hair is a mass <strong>of</strong> wild reddish-brown locks and she carries two great wings, one<br />

<strong>of</strong> which falls from her in her headlong rush as she enters, and the other is later torn from<br />

her by the Squires. Parsifal wears a brown jerkin and breeches, with an animal skin girded<br />

about his waist and a rough battle jacket, apparently made from twigs. His hair is a mass <strong>of</strong><br />

brown dreadlocks roughly tied back and his face is covered with brown and white war paint<br />

which looks effective but makes it hard for the singer to convey emotion.<br />

The direction <strong>of</strong> the scene between Parsifal, Kundry and Gurnemanz is especially<br />

good, bringing out the parallels with their scene in Act III, especially when Kundry brings<br />

water to revive the fainting Parsifal. At “Who is good?” the three are standing in a diagonal<br />

line, with equal spaces between them, and the deep connection between them could not be<br />

shown more clearly. It was uncharacteristic, though, for the usually alert Gurnemanz not to<br />

– 20 –

e allowed to look more surprised at seeing Kundry apparently swallowed up by the earth as<br />

she slides into the open trap which closes behind her.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the production’s most breathtaking moments occurs during the<br />

Transformation. The stage darkens, with a spotlight on Gurnemanz and Parsifal at the front<br />

as they walk on the spot. Behind them the great stone slowly rotates and rolls aside, first to<br />

the left and then to the right, before slowly rising into the flies. The way to the Grail is open<br />

to them, just as Gurnemanz foresaw. But I had to see the production more than once before<br />

realising the other significance <strong>of</strong> this effect: the stone was rolled away. The layers <strong>of</strong><br />

Christian imagery in this moment are astonishing.<br />

The Grail chapel, revealed when the back wall rises during the Transformation music,<br />

is another bleak waste land. The grey flooring curves upwards to form a back wall dotted<br />

with stones and chairs at odd angles, with two vertical gaps which are used for entrances and<br />

exits. Titurel’s appearance, rising from a trap at the centre <strong>of</strong> the stage, is a moment <strong>of</strong> pure<br />

horror: he is a slack-jawed skeleton in gorgeous chain mail whose bony hands grip the edge<br />

<strong>of</strong> the trap. He is hideously indifferent to his son’s despairing agony.<br />

Photo: Richard Hubert Smith, ENO<br />

The Knights file in in regimented columns, re-enacting a ritual which they have all<br />

performed countless times, but when the anguished Amfortas begs to be released from his<br />

burden they break rank, shrinking back from the sinner and all, even Parsifal, pushing him<br />

away when he turns to each in turn in a plea for pity. At Titurel’s pitiless command “Uncover<br />

the Grail!”, they close in upon him, pushing him from one to another, hemming him in until<br />

all that can be seen <strong>of</strong> him is his hands, raised heavenward in despairing supplication. At last<br />

they drive him to the back <strong>of</strong> the group and force him to his knees. (Gurnemanz stands back<br />

from the violence, but does nothing to prevent it). That this scene should take place to the<br />

ethereally beautiful music for the revealing <strong>of</strong> the Grail only serves to heighten its horror.<br />

– 21 –

It is highly significant that the climax <strong>of</strong> the scene has no religious connotation.<br />

There is no bread, no wine, no Communion, no Grail: what we see is more redolent <strong>of</strong> a<br />

selfish drug trip than a shared sacred ritual. To this level the Grail’s devotees have sunk. One<br />

by one the Knights rise and leave, revealing Amfortas lying on his face in a cruciform shape<br />

before the light. He rises and the bandages across his stomach are stained with blood. He<br />

stretches out his hands imploringly to the Knights as they leave, but only Gurnemanz notices<br />

his distress and tries to wrap a blanket around him which he pushes <strong>of</strong>f as he staggers away.<br />

The Knights return in single file, each wearing identical armour like those <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Terracotta Army warriors, with helmets which conceal their faces and carrying spears. (The<br />

Spear may be lost to them, but in its memory a spear is their weapon <strong>of</strong> choice). The process<br />

<strong>of</strong> dehumanisation is complete, and it is chilling. Only Gurnemanz, standing between the<br />

regimented columns <strong>of</strong> marching Knights, wears no armour and remains human. As they<br />

leave Amfortas stumbles towards his father, but Titurel turns from him and sinks into the trap.<br />

Amfortas lies down beside the trap, holding his hand out after him.<br />

Parsifal has watched all this with the liveliest curiosity, moving about the stage to see<br />

everything from every angle. As the Knights file out he picks up the crown which Amfortas<br />

earlier left beside the trap and admires it with childish delight. He has seen everything and<br />

pities Amfortas without yet understanding. At Gurnemanz’s approach he guiltily hides the<br />

crown behind his back and drops it. Gurnemanz angrily sends him away, retrieves the crown,<br />

and walks slowly over to Amfortas. As the heavenly voice sounds above them both raise their<br />

heads in a shared moment <strong>of</strong> hope before Gurnemanz places the crown upon his head. The<br />

simple gold crown seems to be an infinite weight, and Amfortas sinks despairingly across<br />

Gurnemanz’s knees. Gurnemanz gazes down at him in pity but does not touch him. The<br />

grouping as the curtain falls resembles a Pietà.<br />

The opening <strong>of</strong> Act II is visually stunning. The curtain rises to reveal a gauze<br />

depicting an x-ray <strong>of</strong> a woman’s pelvis with Klingsor, framed by a golden hoop, suspended<br />

in the womb.<br />

Photo: Richard Hubert Smith, ENO<br />

– 22 –

The emasculated sorcerer has usurped the very seat <strong>of</strong> creation. In contrast to the allgrey<br />

Brotherhood, he is a riot <strong>of</strong> colour, clad in gorgeous red and white robes which make<br />

him resemble a Kabuki warrior, with striking red and white makeup. At his command<br />

Kundry arises from the depths with only her pale face, topped by a black skull cap, showing<br />

in the darkness. Once they disappear and the gauze rises, the enchantment ends. The set is<br />

virtually the same as it was for the Grail Chapel in Act I with the addition <strong>of</strong> a few dummies<br />

clad in armour like those <strong>of</strong> the Grail Knights to indicate the bodies <strong>of</strong> those whom Parsifal<br />

has slain. There is little to attract any wayward knights from the path <strong>of</strong> righteousness unless<br />

Klingsor’s cunning plan is to mislead them into thinking that they have come home. He plans<br />

to possess the Grail but his theft <strong>of</strong> the spear has turned his own kingdom, as well as<br />

Monsalvat, into an arid waste land.<br />

The Flower Maidens wear identical long, low-necked grey or brown dresses <strong>of</strong><br />

mediaeval cut with sweeping skirts and long, trumpet-like sleeves covering their hands and<br />

reaching to the floor, which resemble the trumpets <strong>of</strong> lilies. These long sleeves are controlled<br />

by rods which protrude from time to time, resembling stamens. It is a pity that their<br />

headdresses are so unattractive. The choreography for this scene is hypnotic, with dancers<br />

cleverly deployed among the singers to maximise the effect as they move about Parsifal, their<br />

sleeves creating complicated patterns, sometimes barring his path. Despite the charm <strong>of</strong> their<br />

singing, this scene has an increasing air <strong>of</strong> menace. Their only additional adornment is the<br />

lighting, which bathes their dull gowns in a golden glow.<br />

Kundry rises from the ground at the back <strong>of</strong> the stage, enveloped in a huge golden<br />

chrysalis above which only her head is visible, topped by a golden helmet and plumes. She<br />

remains in this position until the end <strong>of</strong> the Herzeleide narrative – a good visual effect, but<br />

it is unfair to both singers because it maroons her upstage for far too long while singing very<br />

difficult music and makes it impossible for them to relate to each other. While Parsifal<br />

expresses his remorse she steps out from behind the chrysalis wearing a golden crinoline<br />

with a tight, corseted bodice. It is as though she has been reborn, like a butterfly about to<br />

take its first flight. She keeps her arms pressed close to her sides until the crucial moments<br />

before the kiss, when she extends first one arm, then the other, to reveal vast sleeves like a<br />

butterfly’s wings which seem to hypnotise Parsifal as they envelop him. The potential for<br />

destruction in her kiss is horrifyingly clear, but so too is his ability to destroy, as is shown by<br />

the way he rips her sleeves <strong>of</strong>f as though killing an insect, just as the Squires tore one wing<br />

from her in Act 1. She is left struggling on her back in a position which more resembles a<br />

golden turtle than a butterfly (again, deeply unfair to the singer) until she draws herself clear<br />

<strong>of</strong> the wrecked costume, leaving her in a tight gold corset with flowing skirt, with her black<br />

hair drawn tight about her agonised face. Now at last this scene can, and does, take fire. The<br />

abandoned chrysalis at the back <strong>of</strong> the stage appears in some way to be the source <strong>of</strong> her<br />

powers, as she returns to stand behind it, towering over it, as she summons Klingsor.<br />

Unfortunately the end <strong>of</strong> the act is a terrible anticlimax. Klingsor enters on foot<br />

carrying the spear which Parsifal wrests from him after the tamest <strong>of</strong> struggles, and the allpowerful<br />

sorcerer collapses and dies without so much as a whimper. Parsifal drives the point<br />

<strong>of</strong> the spear into the ground, but as the set is so poverty-stricken, all that can happen to<br />

destroy Klingsor’s “deceitful display” is that some <strong>of</strong> the chairs fall, Kundry’s chrysalis<br />

collapses, leaving her grovelling on the ground, and an endless shower <strong>of</strong> blackened petals<br />

drifts down to denote the demise <strong>of</strong> the flower maidens. The one truly inspired idea at this<br />

point, is that during the final bars, Kundry curls up to fall into the “sleep <strong>of</strong> death” from<br />

which Gurnemanz will eventually awaken her.<br />

– 23 –

In Act III, as Parsifal says, everything is altered. A huge section has been cut out <strong>of</strong><br />

the floor and back wall, leaving a gaping black void from which a railway line, supported at<br />

its rear on girders, extends to the front <strong>of</strong> the stage on the right-hand side. The tracks and<br />

sleepers are broken at the end and shattered pieces lie about. Monsalvat is, literally as well<br />

as figuratively, at the end <strong>of</strong> the line, and Kundry, covered in white draperies, lies at its<br />

terminus.<br />

A pit to the left <strong>of</strong> the stage contains several figures from the Terracotta Army, some<br />

broken, stacked like toy soldiers in a box. One wonders whether they are Knights who have<br />

turned to stone because the Grail was denied to them. Gurnemanz sits watching them like a<br />

guardian <strong>of</strong> the dead, a huge robe draped over him so that he, too, resembles a statue. When<br />

he first hears Kundry’s groan he does not stir, as though any movement is too much effort<br />

after sitting immobile for so long. When she cries out again he rises, goes to her, and does<br />

his best to revive her, but her position between the tracks makes it awkward for him to reach<br />

her. She lurches to her knees with a shriek. She now wears a crumpled white gown with a<br />

long train and is swathed in layers <strong>of</strong> white drapery, almost as though she were a mummy.<br />

Her dangerous beauty is gone, and her plain face is serene. She wears a close-fitting cap from<br />

beneath which pure white hair cascades to her waist. Gurnemanz, <strong>of</strong> course, grumbles at her<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> thanks for restoring her to life, but does not realise how the need to help her has<br />

brought him back to life too.<br />

Parsifal enters, walking slowly along the railway track, carrying the Spear and<br />

wearing elaborate black armour. He is utterly exhausted, and when he at last removes his<br />

helmet, his pale face is lined with care and his eyes are heavily shadowed. Whatever he has<br />

undergone since leaving Klingsor’s domain, it has marked him irrevocably. Even the<br />

knowledge that he has reached his goal brings him little relief. His relationship with Kundry<br />

is developed most beautifully in this scene, as one senses her bringing him, too, back to life.<br />

She prostrates herself before him when Gurnemanz anoints him as King, is utterly astonished<br />

when he baptises her, and sinks to the ground, sobbing, then rises and comes forward, her<br />

arms spread wide in rapture, her pale face radiant. One feels the sense <strong>of</strong> release flooding<br />

through her. She sits at the front <strong>of</strong> the tracks and during Gurnemanz’s Good Friday solo<br />

Parsifal approaches her and takes her tenderly in his arms, resting her head upon his shoulder,<br />

almost as though she were a child. There is a sense <strong>of</strong> the absolute love and trust between<br />

them.<br />

The bells sound and Gurnemanz leads Parsifal and Kundry away, down into the black<br />

void beneath the railway line. For some time the stage is left empty, then Amfortas stumbles<br />

in along the track. He takes refuge in the pit containing the statues from which he lifts the<br />

tiny, shrivelled form <strong>of</strong> the dead Titurel. The voices <strong>of</strong> the chorus sound somewhere in the<br />

void before they begin to emerge from the darkness and struggle up the steps onto the stage.<br />

They are now dressed as soldiers from the First World War, wearing long grey coats which<br />

echo their Act I costumes, with knapsacks, equipment belts and helmets with gas masks. It<br />

is like watching John Singer Sargent’s painting, “Gassed”, coming to life. A seemingly<br />

endless tide <strong>of</strong> wrecked, shattered humanity pours onto the stage while the music tolls out<br />

remorselessly. Their cries <strong>of</strong> “Just one last time!” still haunt me. It is shattering.<br />

Through their sufferings, the Knights have become human again, but their selfish<br />

persecution <strong>of</strong> Amfortas remains unchanged. While he laments over his father they stand, sit<br />

or lie in ragged groups around the stage, their former rigid discipline forgotten, either<br />

ignoring him or watching with increasing impatience until, as before, they turn on him in a<br />

solid mass, pinning him into the centre <strong>of</strong> the group. Some have their backs towards the<br />

– 24 –

audience, and their goggles and gas masks glinting on the backs <strong>of</strong> their helmets make them<br />

look eerily inhuman again. Just as Amfortas is about to succumb Parsifal appears, walking<br />

slowly along the track, carrying the spear, with Gurnemanz and Kundry behind him.<br />

Gurnemanz follows him onto the stage but Kundry remains on the track, apart from the rest.<br />

The ending, so different in this production from what <strong>Wagner</strong> wrote in the libretto,<br />

has divided opinion, but I find it enthralling. The spear never touches Amfortas’ wound.<br />

Parsifal ceremoniously gives it to Gurnemanz, who bears it to the centre <strong>of</strong> the stage and<br />

stands like a sentinel, gazing up at the tip. The knights gather around him and kneel<br />

reverently. Parsifal approaches Amfortas who places his crown upon Parsifal’s head,<br />

embraces him, and dies in his arms.<br />

It is Amfortas, not Kundry, who finds the peace <strong>of</strong> death. Full <strong>of</strong> compassion, Parsifal<br />

lays the dead king upon the ground and gently closes his eyes, an overwhelmingly moving<br />

moment. He crosses the stage to the body <strong>of</strong> Titurel, takes <strong>of</strong>f the crown and lays it upon the<br />

corpse. He will not stay in the place which has destroyed the man whose suffering taught him<br />

pity. He looks up and sees Kundry watching him. She holds one hand out to him then turns<br />

and begins to walk slowly away along the track. He slowly follows her out and a strong light<br />

shines onto their faces as they go. One knight looks round at them, rises, crosses to look at<br />

Amfortas and then at Titurel, and follows them. One by one, three more do the same. As the<br />

curtain falls, a fifth knight rises, and who knows how many more may follow after them?<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> them will remain with what they know, and surely Gurnemanz will govern the<br />

Brotherhood well, but there will always be an adventurous few who will strike out to the<br />

world beyond. Who can tell where they are going? Inevitably in a <strong>Wagner</strong>ian context, the<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> a railway line suggests a concentration camp, but the light towards which they<br />

walk suggests a brighter future. As at the conclusion <strong>of</strong> Goethe’s Faust, the eternal woman<br />

leads them on.<br />

The production has been completely recast since the last run, twelve years ago, and a<br />