13895 Wagner News 174 - Wagner Society of England

13895 Wagner News 174 - Wagner Society of England

13895 Wagner News 174 - Wagner Society of England

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

No: 206 July 2012

Number 206 July 2012<br />

INSIDE<br />

4 From the Committee Andrea Buchanan<br />

5 <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Website Ken Sunshine<br />

6 2012 Prague Congress Andrea Buchanan<br />

8 2013 Leipzig Congress Andrea Buchanan<br />

9 Travel for the Arts <strong>of</strong>fer to members Roger Lee<br />

10 ENO Holländer Guide review Andrew Medlicott<br />

11 ENO Opera Guides <strong>of</strong>fer to members<br />

12 <strong>Wagner</strong> Dream Karel Werner<br />

14 “<strong>Wagner</strong>jobs” + <strong>Wagner</strong> at the Proms<br />

15 Parsifal in Cardiff Bill Bliss<br />

16 Parsifal at the Barbican Katie Barnes<br />

28 Parsifal: “Total Immersion” Paul Dawson-Bowling<br />

22 Dan Sherman: <strong>Wagner</strong> at The Met Andrea Buchanan<br />

23 Oxford <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> concert Roger Lee<br />

24 ENO Dutchman Katie Barnes<br />

28 Forthcoming <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> events Andrea Buchanan<br />

30 New York Metropolitan Opera Ring Richard Miles<br />

31 Fulham Opera Die Walküre Robert Mansell<br />

32 Bayreuth Bursary Auditions Andrea Buchanan<br />

34 Tristan at Cardiff Bill Bliss<br />

35 Translating <strong>Wagner</strong> Katherine Wren<br />

36 DVD review: The Lübeck Ring Chris Argent<br />

40 Bayreuth booking methods Adrian Parker<br />

41 Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Hans Vaget talk Richard Everall<br />

42 Tristan at Aachen and Birmingham Paul Dawson-Bowling<br />

44 Das Geheimnis der Liebe: The Mystery <strong>of</strong> Love Chris Argent<br />

45 Dame Gwyneth Jones’ <strong>Wagner</strong>in project Roger Lee<br />

46 Essential <strong>Wagner</strong>: Turns David Edwards,<br />

Lionel Friend<br />

48 Israel <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong>’s cancelled concert Jonathan Livny<br />

49 German tuition <strong>of</strong>fer for members Katja Wodzinski<br />

50 Interview with Anthony Negus Michael Bousfield<br />

54 Presteigne Weekend: 21st to 24th September<br />

55 <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Contacts<br />

56 Diary<br />

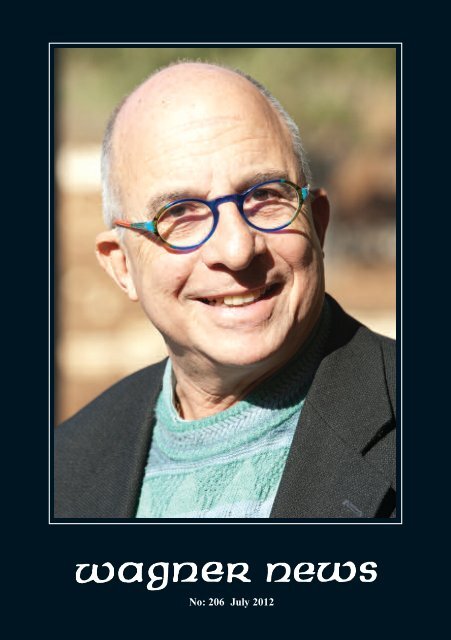

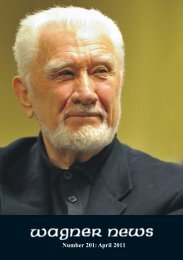

Cover: Jonathan Livny, Founder <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> Israel (See: page 48)<br />

Printed by Rap Spiderweb – www.rapspiderweb.com 0161 947 3700<br />

–2–

EDITOR’S NOTE<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the contributors to this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>News</strong> is<br />

Jonathan Livny who is pictured on the front cover. As the son <strong>of</strong><br />

a Holocaust survivor he is among those whose lives were<br />

atrociously damaged from the 1930s onward by the actions <strong>of</strong><br />

the Third Reich and those who did the bidding <strong>of</strong> its leaders.<br />

No sane and rational person could possibly wish to add to the<br />

suffering endured in these eight decades by so many <strong>of</strong> our<br />

fellow human beings the world over.<br />

The work <strong>of</strong> a composer who challenges us with the proposition<br />

that love has supremacy over power can inspire all <strong>of</strong> us to take<br />

up the duty <strong>of</strong> dismantling the legacy <strong>of</strong> fascism which has so<br />

blighted human history. It is the responsibility <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> us to<br />

work for a future for all such victims which frees them from the<br />

agony <strong>of</strong> their past.<br />

Discussions aimed at helping to relieve such people <strong>of</strong> burdens<br />

which they have carried since the darkest years <strong>of</strong> the twentieth<br />

century demand the utmost in respect and sensitivity. To have<br />

the remotest prospect <strong>of</strong> success such engagement could only be<br />

attempted by those who can identify with the people whose lives<br />

were so severely damaged or destroyed during the Nazi era.<br />

Fully qualified on this account is Daniel Barenboim, whose<br />

work with the East-West Divan Orchestra which he founded<br />

with Edward Said ten years ago is surely worthy <strong>of</strong> recognition<br />

in Nobel Peace Prize terms. In his footsteps now treads Jonathan<br />

Livny who founded the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> Israel a couple <strong>of</strong><br />

years ago. He passionately believes that the people <strong>of</strong> Israel are<br />

as entitled as everyone else in the world to opportunities to<br />

listen to Richard <strong>Wagner</strong>’s life-affirming music and it is his aim<br />

to <strong>of</strong>fer them the chance to do so.<br />

Livny’s courage and that <strong>of</strong> his musicians in pursuing this aim<br />

was demonstrated by their recent attempt to break the taboo on<br />

performing <strong>Wagner</strong>’s music in Israel. Such a taboo serves to<br />

perpetuate a pernicious form <strong>of</strong> cultural confinement and<br />

deprivation upon the people to which it is applied.<br />

The cancellation <strong>of</strong> a planned <strong>Wagner</strong> concert in Tel Aviv was<br />

widely reported by the world’s news media. On page 48 you can<br />

read Jonathan Livny’s own account <strong>of</strong> this affair which he has<br />

written specially for <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>News</strong>.<br />

–3–

NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> the Minutes <strong>of</strong> the Committee Meeting held on 25th April 2012<br />

Andrea Buchanan<br />

The Committee held a regular meeting on 25th April in central London. All members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Committee were present, with the exception <strong>of</strong> Roger Lee and Ge<strong>of</strong>frey Griffiths.<br />

The minutes <strong>of</strong> the January 18th and February 28th meetings were approved and the<br />

ensuing actions were reviewed.<br />

The Committee voted on the proposal to elect Richard Miles as Chairman Elect <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> subject to ratification by members at the forthcoming AGM. Richard’s<br />

nomination was proposed by Andrea Buchanan and seconded by Malcolm Rivers. The<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the Committee present at the meeting voted unanimously to accept this<br />

proposal. Richard then took over as Acting Chair from Andrea Buchanan.<br />

The Secretary reported on past and future events. The Vaget and Sherman events had<br />

both been a financial success and were highly enjoyable. The Committee discussed<br />

forthcoming events, planning for which was going well. It is hoped that the Dame Eva<br />

Turner lecture would be revived in January or February 2013 and discussion took place<br />

around the choice <strong>of</strong> a suitable speaker.<br />

The Secretary reported further on member feedback, progress with the 2012 Bayreuth<br />

Bursary, the Bayreuth tickets situation and the Library. There were no unforeseen or<br />

controversial issues to report with any <strong>of</strong> these items. The Bayreuth tickets situation had not<br />

changed, and would be discussed extensively at the forthcoming Congress, as there was<br />

deep dissatisfaction with the treatment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies by the Bayreuth management.<br />

The Treasurer presented the unsigned final accounts for 2011 which would be mailed<br />

to members in a short form in mid May, well in advance <strong>of</strong> the AGM in June. The <strong>Society</strong>’s<br />

financial position remained healthy, and slightly better than had been anticipated.<br />

The Membership Secretary reported a notable decline in membership renewals in the<br />

year to date, continuing a declining trend over the last few years. It was agreed that this issue<br />

and the aging pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> our membership would need to be addressed.<br />

Malcolm Rivers reported on Mastersingers activities that related to the <strong>Wagner</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong>. Plans were well underway for the exciting programme <strong>of</strong> events to be held in 2013,<br />

highlights being participation in the birthday concert on May 22nd at the Festival Hall,<br />

(when the <strong>Society</strong> also hopes to host a celebration lunch) and involvement with the<br />

Longborough Ring Cycles. Further details would be communicated to members over the<br />

next few months.<br />

The Committee discussed the need to find volunteer photographers and would<br />

canvass all members to let us know whether they could assist in this regard. We also seek a<br />

new Committee member to undertake publicity and a communication inviting members to<br />

apply would be mailed out with the accounts in May.<br />

Planning for the forthcoming AGM was discussed and it was noted that the President<br />

would not be able to attend, due to the change in date and her current work commitments.<br />

All members <strong>of</strong> the Committee would stand for re-election.<br />

The Acting Chair presented his mission statement to the Committee and this was<br />

discussed. It would be mailed out to all members with the accounts prior to the AGM.<br />

Financial support for various <strong>Wagner</strong> related activities was discussed and with this the<br />

meeting drew to a close.<br />

–4–

THE WAGNER SOCIETY WEBSITE<br />

Ken Sunshine<br />

When Wotan wanted to know something he consulted Erda. When I want to find out<br />

something I consult the internet. If it’s to do with <strong>Wagner</strong> I go to the <strong>Society</strong> website:<br />

www.wagnersociety.org which, after a busy two months, has stabilised into its new<br />

structure and now contains a substantial and growing amount <strong>of</strong> information on things<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong>ian. We are continuing to add new data and new links, but for this to be<br />

worthwhile the information has to be useful, relevant, easily accessible, and actually<br />

accessed and read. We have made information available which I believe conforms to the<br />

first two criteria. I hope it is easily accessible even to those <strong>of</strong> you who would claim to be<br />

computer illiterate but I would appreciate feedback where you feel things are too<br />

complicated.<br />

To access the site use a browser such as Internet Explorer or Firefox and enter<br />

www.wagnersociety.com to load the ‘home’ page.<br />

Then what? Via the menu bar down the left hand side or via the ‘links’ in the table, you<br />

can go directly to any <strong>of</strong> the major headings. Just click on any word which, when your<br />

mouse pointer turns to a hand, indicates a link. Most pages display the sidebar menu<br />

which can take you ‘home’ or to any <strong>of</strong> the major headings.<br />

What information is available? The best way for you to answer that question is to<br />

explore the site, clicking your way around. Note that some headings in the sidebar display<br />

sub-links when pointed at. Did you know we have a Forum? Past editions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong><br />

<strong>News</strong>? Access to an extensive Audio and Video library?<br />

What do you want on your site? Tell me what’s missing, what you like / don’t like.<br />

Let me know about any problems you have.<br />

–5– – 5–

REPORT ON THE ANNUAL CONGRESS OF THE<br />

RICHARD WAGNER VERBAND INTERNATIONAL<br />

Prague, May 17th to 20th 2012<br />

Andrea Buchanan<br />

President <strong>of</strong> the RWVI Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Eva Märtson opened the<br />

Annual General Meeting by welcoming the Chairs and<br />

Secretaries <strong>of</strong> various <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies. Those Chairs who had<br />

been newly appointed since the last AGM were then given the<br />

opportunity to introduce themselves. Reporting the Activities <strong>of</strong><br />

the President and the Executive Committee during the past year,<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Märtson emphasised the importance <strong>of</strong> newlyfounded<br />

University <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies (notably Oxford,<br />

Cambridge and Erlangen-Nürnberg). An account <strong>of</strong> various<br />

activities in this area was given by Ute Bergfeld, member with<br />

responsibility for the Universities Programme, who stressed<br />

that engaging with student Societies was a good way forward.<br />

Marcus-Johannes Heinz, the outgoing Secretary and<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Eva Märtson<br />

Webmaster <strong>of</strong> the Verband, also noted the work that he had been<br />

undertaking in the field <strong>of</strong> social media in order to promote the<br />

Verband to a younger audience.<br />

There followed a brief presentation <strong>of</strong> the statistics relating to membership<br />

numbers <strong>of</strong> the various Societies. Total membership <strong>of</strong> the Verband is currently just under<br />

24,000. If any members would like to see these statistics, I would be happy to e-mail this<br />

information to them.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Schneider continued by giving an update on progress with the<br />

International Competition for <strong>Wagner</strong> voices in Karlsruhe. He noted that the competition<br />

committee had recently chosen 36 singers from 110 entries to progress to the next round,<br />

to be held in Bayreuth in August. Members will be pleased to hear that our Bayreuth<br />

Bursary winner, Helena Dix, is among those chosen.<br />

The next agenda item related to the Bayreuth ticket situation. Herr Peter Emmerich,<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Bayreuth management committee, who was originally to have been present at the<br />

meeting, had declined to attend at the last minute as he stated that he had nothing new to<br />

report. It seemed that the outlook was currently not particularly favourable and that the<br />

protests that the Bayreuth management had received from various <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies were<br />

not well received. A meeting had been held in April between members <strong>of</strong> the Praesidium<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Verband and the Festival management, during which the latter complained that the<br />

tone <strong>of</strong> the various communications from individual societies had not been helpful. The<br />

Festival management had explained that they had no choice in making the decision to<br />

discontinue ticket allocations to <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies, as they were under pressure from both<br />

central and regional government (both <strong>of</strong> whom subsidise the Festival) to make the ticket<br />

system more democratic. There remained however a lack <strong>of</strong> clarity as to how this worked<br />

in practice and who had the decision-making power. Approaches were now being made on<br />

a political level and the Verband would continue to lobby on behalf <strong>of</strong> its members.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Märtson had written a letter to the German Minister <strong>of</strong> Culture, which all the<br />

delegates were asked to sign. This initiative was supported by all those present.<br />

–6– – 6–

The meeting moved on to consider the accounts, presented by the Treasurer, Herr<br />

Horst Eggers. These documents had been circulated in advance. The general position was<br />

healthy, with a reasonable surplus for 2011. A number <strong>of</strong> Societies had not paid their<br />

membership dues, although it was expected that most <strong>of</strong> these would eventually pay. He<br />

noted that 5,000 euros had been donated by the Verband towards renovation works to the<br />

Wahnfried Museum in Bayreuth and that the Verband had also contributed to the staging<br />

<strong>of</strong> a major exhibition devoted to Martha Mödl. The auditors had approved the 2011 annual<br />

report in February 2012. The Treasurer was optimistic that 2012 would also prove to be a<br />

financially sound one for the Verband. A budget had been requested for future years by<br />

the Chair <strong>of</strong> the Danish <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> and Herr Eggers noted that he supported this<br />

suggestion and would look into the matter. Anthony Linehan (Chair, <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Ireland) asked that the accounts be presented in English and French in future years and it<br />

was agreed that this would be arranged. The accounts were accepted by the members, with<br />

one abstention.<br />

Dr Specht then spoke about the Bursary arrangements for 2012, which were<br />

progressing well. The Festival had guaranteed 1000 tickets for the Bursary winners and<br />

their mentors and the Verband was grateful for this concession. He explained that the<br />

process <strong>of</strong> allocating these tickets had been complicated, and therefore had taken longer<br />

than foreseen, for which he apologised. 250 scholarships had been given this year to<br />

young artists: 49 to German candidates, 23 to East European and 26 to other European<br />

countries.<br />

The resignation <strong>of</strong> Marcus-Johannes Heinz, the Secretary was<br />

then announced and a new candidate, Philippe Olivier<br />

(Strasbourg) was nominated. Dr. Olivier duly introduced<br />

himself. He is French, although a fluent German speaker and<br />

will no doubt contribute to the already close relationship<br />

between the French and German members <strong>of</strong> the Verband. He<br />

also mentioned that he would engage in political lobbying<br />

within the EU as and when appropriate and was keen to develop<br />

the pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> the Verband in this area. As he was the only<br />

candidate he was duly voted in to the role <strong>of</strong> Secretary.<br />

The meeting then moved on to presentations <strong>of</strong> future<br />

Congresses, beginning with Leipzig in 2013. Thomas Krakow,<br />

Dr Philippe Olivier<br />

the President <strong>of</strong> the Leipzig WS spoke at some length about the<br />

extensive and culturally rich programme for next year. Graz<br />

would follow in 2014 and Hans Weyringer seduced us with the<br />

potential charms <strong>of</strong> the place, and the added interest <strong>of</strong> a young directors <strong>Wagner</strong> staging<br />

competition to be held during the Congress. Dessau would follow in 2015, with the<br />

prospect <strong>of</strong> a full “Bauhaus” Ring Cycle.<br />

There followed a motion proposing that the different Verbände submit reports on<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> performances in their areas to the RWVI. This was defeated on the basis that it<br />

would constitute too onerous a task. The delegate from Milan proposed that Workshops be<br />

held at Congress to discuss topics such as the reaction to recent <strong>Wagner</strong> productions in<br />

Bayreuth. The delegates were not however in favour <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial discussions <strong>of</strong> productions<br />

as this was not felt to be the business <strong>of</strong> the Verband. The Parisian delegation reported that<br />

they had asked for the City to rename a major street as rue Richard <strong>Wagner</strong>. This request<br />

had not yet been successful. With this the meeting ended.<br />

–7– – 7–

“RICHARD IST LEIPZIGER”<br />

International Richard <strong>Wagner</strong> Congress 2013<br />

Andrea Buchanan<br />

Members <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies are most welcome and are indeed encouraged to attend the<br />

annual Congresses. There is, I think, a perception among our members that these events<br />

are only for the Committee and that the event consists mainly <strong>of</strong> business meetings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

International Richard <strong>Wagner</strong> Verband. This is absolutely not the case as the Congress is<br />

also very much a cultural event with many operas and concerts on <strong>of</strong>fer, as well as plenty<br />

<strong>of</strong> tours and visits to places <strong>of</strong> musical and historical interest in the area in which the<br />

Congress is held.<br />

Provided you can arrange your own travel, booking is a very simple process and<br />

the prices are extremely competitive. Many <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Wagner</strong> Societies from countries such<br />

as Germany and France attend the annual Congresses in large groups and the members<br />

always seem to enjoy the event very much.<br />

I particularly wanted to bring next year’s Congress to your attention as it promises<br />

to be a very exciting and culturally rich event. It is being held in Leipzig, the city <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Wagner</strong>’s birth and the city itself, the States <strong>of</strong> Saxony and Thuringia and the Richard<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> Verband International are all supporting and endorsing the event, extending a<br />

warm welcome to <strong>Wagner</strong> lovers from around the world.<br />

The programme begins on May 17th with a performance <strong>of</strong> The Ring Without<br />

Words, by Lorin Maazel performed by the famous Gewandhaus Orchestra, conducted by<br />

Ulf Schirmer, which will be followed by extracts from Parsifal. On the afternoon <strong>of</strong> 18th<br />

May the Thomaner Choir <strong>of</strong> Leipzig will perform a motet with works by <strong>Wagner</strong>, Weinlig<br />

and Biller in the Thomaskirche, while in the evening there will be a performance <strong>of</strong> Das<br />

Rheingold at the Leipzig Opera.<br />

Die Meistersinger follows on the 19th May with the alternative choice <strong>of</strong> an organ<br />

recital at the Gewandhaus, while Parsifal can be seen on the 20th. The Leipzig <strong>Wagner</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> will host a gala evening on the 21st and musical events will conclude with a<br />

performance <strong>of</strong> Götterdämmerung on the 22nd. In between this feast <strong>of</strong> operas there are<br />

tours every day within Leipzig and to places <strong>of</strong> interest in the region as well as lectures,<br />

exhibitions, academic conferences and symposia.<br />

I would like to encourage our members to consider attending. While I am aware<br />

that there will be many demands on both the time and the purses <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> lovers in<br />

2013, the Leipzig Congress <strong>of</strong>fers a superb range <strong>of</strong> events at reasonable prices. The<br />

booking arrangements are completely flexible, such that participants can choose which<br />

events they wish to attend and pay according to what they book. There is a range <strong>of</strong><br />

discounted prices on <strong>of</strong>fer for hotels, from 3 stars (€112.50 for a double) to 5 stars (€293<br />

for a deluxe double), and tickets for the operas range from €28 to €86. Participants are<br />

also free to book their own accommodation.<br />

I have a brochure for this event containing full details and I would be happy to<br />

email this, along with booking forms, to members on request. Alternatively, see the event<br />

website on http://www.wagner-verband-leipzig.de/ I should <strong>of</strong> course mention that The<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> will be holding its own birthday celebrations on 22nd May 2013 at the<br />

Festival Hall (see back page for announcement) and that it will be entirely possible to<br />

attend Leipzig and to return in time for this special day in London.<br />

–8– – 8–

SPECIAL OFFER FOR WAGNER SOCIETY MEMBERS<br />

Roger Lee<br />

Travel for the Arts have launched their 2013 special brochure <strong>of</strong> tours to celebrate the<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> bicentenary, and have announced a price reduction <strong>of</strong> 5% for members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong>. Established in 1988 to arrange excursions for the Friends <strong>of</strong> Covent<br />

Garden, Travel for the Arts now organise over 100 tours per year. Their <strong>Wagner</strong> brochure<br />

lists 16 different tours in 2013 to many <strong>of</strong> the important <strong>Wagner</strong>ian destinations.<br />

Full Ring cycle tours are available to Frankfurt (6th-14th February), Halle (2nd-<br />

10th March), Hamburg (26th May-3rd June), Riga (3rd-10th June) and Milan (17th-23rd<br />

June). As with all such packages, local guided tours are included. There is a novel way to<br />

attend the new Opéra de Paris Ring as a series <strong>of</strong> day trips between February and June.<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong>’s Birthday on 22nd May is celebrated with a ceremony at Leipzig Oper<br />

and a performance <strong>of</strong> Parsifal with options to extend the tour to include Die Feen, Rienzi,<br />

Der fliegende Holländer, and a specially devised ballet: Ertrinken…Versinken! to music<br />

by <strong>Wagner</strong>. An alternative programme: “<strong>Wagner</strong>’s Birthday in Dresden and Weimar” is<br />

available from 18th to 23rd May.<br />

A new production <strong>of</strong> Der fliegende Holländer with Bryn Terfel and Anja Kampe<br />

in Zürich on 11th January is paired with Tannhäuser on 13th with a walking tour <strong>of</strong> the<br />

old town in between. “<strong>Wagner</strong> in Thuringia” from 16th to 21st May <strong>of</strong>fers Siegfried Idyll,<br />

Tristan und Isolde and Tannhäuser in Meiningen and Eisenach.<br />

“<strong>Wagner</strong> in Munich” from 27th to 30th June adds visits to Neuschwanstein and<br />

Hohenschwangau castles to Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser at the Bayerisches<br />

Staatsoper. “<strong>Wagner</strong> in Dresden” from 4th to 8th July adds a new production <strong>of</strong> Der<br />

fliegende Holländer at Semperoper to concerts at the Albertinum and the Frauenkirche.<br />

“<strong>Wagner</strong> in Bayreuth” from 7th to 10th July consists <strong>of</strong> Rienzi, Das Liebesverbot<br />

and Die Feen at Oberfrankenhalle along with daytime walking trips. A concert Ring in<br />

Lucerne from 29th August to either 1st or 5th September includes a cruise on the lake to<br />

Villa Tribschen.<br />

Members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> will receive 5% <strong>of</strong>f the price <strong>of</strong> any tour listed in the<br />

Travel for the Arts 2013 <strong>Wagner</strong> brochure for which places are available. To claim your<br />

discount contact Travel for the Arts by phone or email and quote “<strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong>” with<br />

your membership number.<br />

–9– – 9–

NEW ENO GUIDE TO DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER<br />

Andrew Medlicott<br />

In association with English National Opera, Overture Publishing is reworking and<br />

updating the Opera Guides series originally published between 1980 and 1994. This guide<br />

to Der fliegende Holländer has been published to mark the recent new production by<br />

ENO. In a prefatory note series editor Gary Kahn writes “The aim <strong>of</strong> the present<br />

relaunched series is to make available again the guides already published in a redesigned<br />

format with new illustrations, some newly commissioned articles, updated reference<br />

sections and a literal translation <strong>of</strong> the libretto...”<br />

Jokes about <strong>Wagner</strong>ian length are <strong>of</strong> course wholly inapplicable to Holländer,<br />

which is short not only by <strong>Wagner</strong>'s standards, but everyone’s. Nevertheless, there is a<br />

huge amount <strong>of</strong> ground to cover. This guide does so in less than 200 paperback pages.<br />

They include: thirty one pictures; three articles from the original guide by John Warrack,<br />

John Deathridge and William Vaughan; two new articles by Mike Ashman and Katherine<br />

Syer; <strong>Wagner</strong>'s own comments on the overture and performance <strong>of</strong> the opera, from the<br />

original guide, translated by Melanie Karpinski; a thematic guide; the libretto and Lionel<br />

Salter's translation <strong>of</strong> it; a discography; a guide to DVDs; a bibliography; and<br />

identification <strong>of</strong> websites.<br />

The five essays have much thought-provoking material. Perhaps the most startling<br />

suggestion is still by John Warrack. The conventional view <strong>of</strong> the opera (as repeated in<br />

the first sentence <strong>of</strong> the book’s blurb) is that ‘it is the first <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong>’s operas considered<br />

to be representative <strong>of</strong> his mature style’. But Warrack writes ‘The Dresdeners, delighted<br />

with the grandiose Rienzi...were disconcerted by what they saw as a reversion to an older,<br />

even a quainter, German Romanticism’. He does later write ‘A few in the city were to<br />

sense the bold new ideas that dominated [the opera]...but in 1843 its day had not yet<br />

come.’ Mike Ashman, on the same point in his article ‘How <strong>Wagner</strong> found the Flying<br />

Dutchman’ writes ‘...the new work’s eventual acceptance was guaranteed by the fact that<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> had at last got his hands upon a genuinely popular subject.’ William Vaughan’s<br />

and Mike Ashman's articles to some extent cover the same ground, the multitudinous<br />

influences on <strong>Wagner</strong>, but Vaughan’s is more literary, Ashman’s more factual. Katherine<br />

Syer’s article is a stage history.<br />

‘The guide also contains the libretto and Lionel Salter's non-singing English<br />

translation. I warmly welcome the decision to abandon ‘singing translations’ in these<br />

guides. If a translation is to be sung, it must be a singing translation, with all the<br />

alarmingly severe constraints and occasional reluctant compromises that involves. But<br />

where the translation is simply to reveal what the original means, without having to fit the<br />

music, the greater freedom for the translator is better for the listener/reader. The thematic<br />

index identifies 40 musical themes, which are signalled by number throughout the libretto<br />

and in John Deathridge’s ‘Introduction’. This is largely a musical account <strong>of</strong> the opera,<br />

but also includes an interesting outline <strong>of</strong> the many occasions during the rest <strong>of</strong> his life,<br />

on which <strong>Wagner</strong> returned to the opera and made changes. Deathridge’s argument is that<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong>'s motivation was to make the opera seem more like a worthy precursor <strong>of</strong> music<br />

drama than it actually is – an aim in which, according to Deathridge, he failed.<br />

This guide is an excellent piece <strong>of</strong> work. I can see it being extremely helpful to<br />

newcomers, while also having much to interest old hands (pun intended).<br />

– 10 –

WAGNER’S DREAM OR WAGNER’S NIGHTMARE?<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Karel Werner<br />

It is well known that <strong>Wagner</strong> was, on and <strong>of</strong>f, preoccupied with the idea <strong>of</strong> writing a<br />

Buddhist opera, Die Sieger (The Victors), after becoming acquainted with<br />

Schopenhauer’s philosophy (Sept. 1854), which he supplemented by a study <strong>of</strong> Eugène<br />

Burnouf’s Introduction à l’histoire du Buddhisme indien. He talked about writing and<br />

composing Die Sieger even after completing Parsifal. What his sudden death deprived us<br />

<strong>of</strong> has now been boldly accomplished by Jonathan Harvey in his opera <strong>Wagner</strong> Dream<br />

composed in 2007 to the libretto by Jean-Claude Carrièra and premièred the same year in<br />

Amsterdam. It was given its first showing in this country on 29th January 2012 in the<br />

Barbican Hall, directed by Orpha Phelan, played by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under<br />

the baton <strong>of</strong> Martyn Brabbins and sung by six soloists and a small chorus. <strong>Wagner</strong> here<br />

dreams his last opera while in a coma in the period between his heart attack and death on<br />

13th February 1883 in the Palazzo Vendramin in Venice, while events around him are<br />

shown through protagonists who are actors with speaking roles.<br />

Cosima’s diaries enable us to follow the genesis <strong>of</strong> the idea <strong>of</strong> Die Sieger. In his<br />

programme notes Christopher Cook, in conversation with composer and conductor, uses<br />

them and regards her entry <strong>of</strong> 29th June 1869, according to which <strong>Wagner</strong> said he might<br />

do Die Sieger as a play, as being his first mention <strong>of</strong> the theme. But the entry <strong>of</strong> 2nd April<br />

1875 already suggests it would be an opera. On 27th February 1880 Cosima records: ‘R.<br />

relates to us the story underlying his Sieger, wonderful and moving’ ... the opera ‘will be<br />

gentler than Parsifal’. On 6th January 1881, a year before completing the score <strong>of</strong> Parsifal<br />

at Palermo, <strong>Wagner</strong> again promises to compose Die Sieger if Cosima will look after him<br />

well, and he speaks about the fact that both stories are about the redemption <strong>of</strong> a woman.<br />

The libretto combines the story, which <strong>Wagner</strong> took for his sketch from Burnouf,<br />

with Buddhist notions about the process <strong>of</strong> dying as an intermediary stage before the next<br />

incarnation and with known as well as fictional events taking place around <strong>Wagner</strong>’s<br />

unconscious body. First <strong>Wagner</strong> is approached in his intermediary state by the<br />

transcendental Buddha Vairochana, who explains to him that he is free to make some<br />

choices as to his immediate steps. <strong>Wagner</strong> finally decides to compose Die Sieger and the<br />

semi-staged production <strong>of</strong> the opera unfolds.<br />

Prakriti, a young woman, and Ananda, a prince whose cousin, Siddhartha,<br />

renounced the world and became the Buddha, fall in love. The Buddha, who has another<br />

plan for his cousin, appears (seen only by the audience) and turns Prakriti for a moment<br />

into the Tantric goddess Vajrayogini. Overwhelmed, Ananda prostrates himself and<br />

leaves. But Prakriti cannot live without him and she approaches the Buddha, surrounded<br />

by his monks, who now include Ananda. She asks if she can live near Ananda. The<br />

Buddha, always compassionate, explains to her that the rules make it impossible. Taunted<br />

by an old Brahmin watching the scene, Prakriti tries to drag Ananda away. The Buddha<br />

explains the situation by relating a jataka, the story <strong>of</strong> their former incarnation when<br />

Prakriti as a high Brahmin’s daughter, rejected the low-born Ananda, who was wooing her<br />

and who then lived his life alone. Now Prakriti wishes to kill herself, but Ananda<br />

persuades the Buddha to admit women to his order, and Prakriti becomes a nun.<br />

Who, then, are the victors? In the first place the Buddha, who bears also the title<br />

Victor (Jina, as do other renouncers who have reached liberation from further<br />

incarnations) and Ananda, <strong>of</strong> whom tradition says that he was liberated soon after the<br />

– 12 –

Buddha’s death, and presumably also Prakriti, whose passion was calmed by monastic<br />

discipline. (Her name means ‘nature’ and in the original story she may have been a<br />

symbolical figure representing the natural sensual and emotional attachments tying one<br />

to this world <strong>of</strong> suffering and repeated deaths and births.)<br />

Simultaneously with the opera, enacted in <strong>Wagner</strong>’s mind and watched by<br />

Vairochana and the audience, the actual and presumed events <strong>of</strong> the fateful morning are<br />

taking place. So we have here a glimpse into three dimensions: the transcendental one<br />

between incarnations, the realm <strong>of</strong> artistic creation in the artist’s mind and the ordinary<br />

world <strong>of</strong> ‘real’ events. These begin with Cosima’s display <strong>of</strong> jealousy over the arrival in<br />

Venice <strong>of</strong> Carrie Pringle, a flower maiden from the première <strong>of</strong> Parsifal, who had caught<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong>’s eye. Apparently upset, <strong>Wagner</strong> withdraws to his study, contemplating his failure<br />

to realise the opera Die Sieger with its message <strong>of</strong> liberation. After his heart attack when<br />

he becomes unconscious (and starts creating the opera in his mind) Betty the maid enters<br />

and, horrified, summons Cosima, who tries to nurse him. Dr Keppler is called and takes<br />

some measures to revive him. Even Carrie Pringle arrives, but it is not clear whether she<br />

is there in person or as a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong>’s visions. The libretto purports that <strong>Wagner</strong>,<br />

having composed his opera in his mind but unsure whether it was the right thing to be<br />

preoccupied with, briefly regains consciousness and asks Cosima’s forgiveness (a<br />

presumption <strong>of</strong> the libretto). Having physically died, <strong>Wagner</strong> is led in the other dimension<br />

by Vairochana to his future destiny.<br />

The libretto takes some further liberties, for example with the monastic history <strong>of</strong><br />

Buddhism. The Buddha actually allowed ordination <strong>of</strong> women when Ananda persuaded<br />

him to grant it to his, the Buddha’s, aunt and foster mother, who raised him after his mother<br />

died within a week <strong>of</strong> his birth. As to the events around <strong>Wagner</strong>’s death, they have never<br />

been sufficiently clarified. Any written account by Dr Keppler (an independent witness)<br />

which may have existed was presumably suppressed. What would seem clear is that<br />

Cosima had intercepted Carrie Pringle’s letter, from which she learned <strong>of</strong> her arrival in<br />

Venice and possibly some other worrying circumstances and, seized by jealousy, she<br />

created a scene in which she (unusually for her) even raised her voice, causing <strong>Wagner</strong> to<br />

take refuge in his study. This is testified to by his (or von Bülow’s?) daughter Isolde, but<br />

she does not appear in the dying scene in the opera, although it is most unlikely that, being<br />

in the house, she would not rush to the side <strong>of</strong> her father. The appearance <strong>of</strong> Pringle is, by<br />

Jonathan Harvey’s admission, another liberty taken by him and the librettist. Cosima had<br />

noticed Pringle before in a rehearsal and remarks on 5th August 1881 in her diary that she<br />

sang Agathe’s aria very tolerably. So she could easily have caught <strong>Wagner</strong>’s eye. Whether<br />

Cosima sensed some danger at this stage cannot be known. It is also unknown whether<br />

there was a liaison between <strong>Wagner</strong> and Pringle. Harvey regards it as quite likely.<br />

Cosima discontinued her diary from the fateful day, but there is an important<br />

testimony to her state <strong>of</strong> mind after her jealous outburst and <strong>Wagner</strong>’s abrupt withdrawal<br />

into his study. Their son Siegfried was also in the house and was practising on the piano in<br />

the salon at the time, unaware <strong>of</strong> what had been happening between his parents. His mother<br />

came in, sat down at the grand piano and started playing Schubert’s Lob der Tränen (Praise<br />

<strong>of</strong> Tears) with a ‘completely transported’ expression. Siegfried says that he had never heard<br />

her play before as she had been dedicating all her time to her husband’s needs. When the<br />

maid came in with the news <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong>’s collapse, Cosima rushed with an expression <strong>of</strong><br />

passionate anguish to the door, almost splitting it (Siegried <strong>Wagner</strong>, Erinnerungen, 1923,<br />

p. 35ff.). It is most likely that Siegfried was also present in the dying moments <strong>of</strong> his father<br />

– 13 –

at his bedside. Judging from the previous gestation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong>’s masterpieces we can<br />

assume that what <strong>Wagner</strong> needed was another muse to compose his last intended opera.<br />

But what the long-suffering Minna had endured, more or less with resignation, was<br />

unbearable to Cosima and it prompted her outburst with tragic consequences.<br />

I saw Harvey’s Inquest <strong>of</strong> Love in 1993 and I felt that there were some elements <strong>of</strong><br />

spirituality in his music which remotely reminded me by its mood <strong>of</strong> Scriabin and I quite<br />

enjoyed it despite David Pountney’s inept production. This time I was less affected by the<br />

music which apparently owes a lot to electronic treatment, while the vocal parts seemed<br />

to me not much more than intoned speech. The libretto, which was well presented by<br />

surtitles, seemed to me rather pedestrian. One misses <strong>Wagner</strong>’s superb poetry which<br />

sometimes comes through even in translations on surtitles. Nevertheless, the opera was<br />

an interesting experience and I would advise every <strong>Wagner</strong>ite not to miss it if another<br />

opportunity presents itself. The audience showed in sufficient measure its appreciation,<br />

enhanced no doubt by the presence <strong>of</strong> the composer.<br />

WAGNERJOBS<br />

At www.wagnersociety.org you will find the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>News</strong> Forward Planning list <strong>of</strong> the<br />

events we intend to cover in the next half dozen issues <strong>of</strong> the magazine. You will see<br />

which reports still require volunteers to provide the words or the pictures. For example<br />

we need a reviewer for the Opus Arte DVD <strong>of</strong> Lohengrin from the 2011 Bayreuth Festival.<br />

We also need someone who can use music-writing s<strong>of</strong>tware to provide the graphic<br />

examples in pieces such as the “Essential <strong>Wagner</strong>” item on pages 46 and 47 <strong>of</strong> this issue.<br />

Whether it is to join the team reporting the Presteigne weekend for the January<br />

2013 issue <strong>of</strong> the magazine, to photograph the “Great <strong>Wagner</strong> Choruses” event for the<br />

January 2014 <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>News</strong> or to try your hand at any <strong>of</strong> the other dozen or so jobs which<br />

are on <strong>of</strong>fer, we would be delighted to hear from you. The Forward Planning list is<br />

updated on the <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> website as our future programme <strong>of</strong> events unfolds.<br />

WAGNER AT THE PROMS<br />

August is a relatively <strong>Wagner</strong>-rich month at the Proms with five concert performances.<br />

Siegfried Idyll will be played by an 18 musician ensemble as it was at Tribschen on<br />

Christmas morning in 1870 instead <strong>of</strong> the full orchestra versions which we usually hear.<br />

3rd August Prom 27 Siegfried Idyll BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra<br />

Donald Runnicles 18 mins<br />

5th August Prom 31 Meistersinger Overture Nat. Youth Orchestra <strong>of</strong> Scotland<br />

Donald Runnicles 12 mins<br />

7th August Prom 33 Tristan und Isolde BBC Philharmonic Orchestra<br />

Prelude to Act I Juanjo Mena 9 mins<br />

26th August Prom 57 Parsifal Prelude to Act III Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester<br />

and Good Friday Music Danielle Gatti 20 mins<br />

30th August Prom 63 Lohengrin Prelude to Act I Berlin Phil /Simon Rattle 7 mins<br />

– 14 –

CONCERT PERFORMANCE OF PARSIFAL AT CARDIFF<br />

Bill Bliss<br />

Is it possible to enjoy a concert performance <strong>of</strong> Parsifal when those singing the two main<br />

roles: Gurnemanz and Parsifal are clearly not up to the mark? Yes it is when the Mariinsky<br />

Opera is conducted by Valery Gergiev. As has <strong>of</strong>ten been mentioned in this journal,<br />

concert performances have much to recommend them. The music shines through, there<br />

are no distractions from the stage and once again you are reminded that in <strong>Wagner</strong> the<br />

main voice is the orchestra and in the Millennium Centre on 31st March it certainly was.<br />

Gergiev may have been in cruise control but the mellifluous tone he produced from his<br />

orchestra was sublime, never more so than in the final few minutes <strong>of</strong> Act III. But did we<br />

applaud too soon ?<br />

There were two brilliant solo performances. Evgeny Nikitin as Amfortas had a<br />

large voice from a large frame and his contrition and suffering were manifest. I have never<br />

heard such a powerful and malevolent Klingsor as that sung by Nikolay Putilin. (These<br />

two were the only representatives from Gergiev's recent and well-received CD recording).<br />

Larisa Gogolevskaya in the role <strong>of</strong> Kundry was a little strident at the top <strong>of</strong> her range, but<br />

certainly believable. The same could not be said <strong>of</strong> Yuri Vorobiev as Gurnemanz who<br />

never uttered an ugly sound but sweetness <strong>of</strong> tone is not the main requirement for this<br />

role. More heft and solemnity were needed and, at risk <strong>of</strong> being ageist, wasn't he far too<br />

young for the part? August Amonov as Parsifal (too old) was similarly low in volume and<br />

commitment whilst body language was almost totally absent. In Act II there was no need<br />

for him and Kundry to be separated by the conductor's podium as the likelihood <strong>of</strong><br />

anything approaching a look, let alone a kiss, was non-existent.<br />

There are all sorts <strong>of</strong> graduations between concert performances and semi-staged<br />

ones. No one expects costumes and total interaction, but an acknowledgement that the<br />

person you are singing about is on the platform with you does add to the drama. (Didn't<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> write music drama – not opera?) Vivid memories <strong>of</strong> Domingo and Tomlinson<br />

singing and “acting” Parsifal and Gurnemanz at the Royal Festival Hall in 1998 are<br />

fixtures in my memory bank.<br />

From a personal point <strong>of</strong> view the final test <strong>of</strong> a great <strong>Wagner</strong> performance is the<br />

‘next day effect’. Did I feel a little spaced-out and semi-detached from real life? In the<br />

case <strong>of</strong> Gergiev’s Parsifal,undoubtedly: Yes!<br />

WAGNER SOCIETY OF NEW YORK LECTURES AT BAYREUTH<br />

The <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>Society</strong> <strong>of</strong> New York’s 2013 programme <strong>of</strong> lectures will run from 10:30am<br />

to noon on the dates <strong>of</strong> the following performances at the Arvena Kongress Hotel:<br />

August 24th Der fliegende Holländer (new production)<br />

August 25th Lohengrin<br />

August 26th Tristan und Isolde<br />

August 27th Tannhäuser<br />

August 28th Parsifal<br />

Tickets are 12 euros per lecture, payable at the door. No advance reservation<br />

is necessary. The lecturer is John J.H. Muller, who presented the 2010 and<br />

2011 Bayreuth lectures. He has been a member <strong>of</strong> The Juilliard School<br />

music history faculty for 30 years and is a past department chairman.<br />

– 15 –

PARSIFAL Á LA RUSSE<br />

OR THE CURIOUS CASE OF THE MISSING KUNDRY<br />

Mariinsky Opera in concert, Barbican Hall, 3 April 2012<br />

Katie Barnes<br />

The Mariinsky Opera's Ring at the Royal Opera House in 2009 was <strong>of</strong>ten excellent,<br />

frequently intriguing, but patchy. My expectations for this concert performance were<br />

consequently not pitched too high. But this was music-making <strong>of</strong> quite a different order<br />

to that uneven experience. Where his Ring was choppy, Gergiev's Parsifal was composed<br />

<strong>of</strong> long, stately, gracious arches <strong>of</strong> music.<br />

The brightness <strong>of</strong> the solo trumpet stood out against the depth <strong>of</strong> the other brass<br />

instruments, its edginess giving the s<strong>of</strong>t, lapping sounds <strong>of</strong> the Prelude a suitable sense <strong>of</strong><br />

unease, and the massed brasses for the Dresden Amen sounded majestic. The wonderful,<br />

sonorous strings were gentle, s<strong>of</strong>t and caressing, but capable <strong>of</strong> creating huge, supple<br />

waves <strong>of</strong> sound. Gergiev and his forces created a realm <strong>of</strong> sound which enclosed the<br />

audience from the outside world, just as the Grail knights are enclosed from the world in<br />

Monsalvat.<br />

I was moved to wonder what <strong>Wagner</strong> would have made <strong>of</strong> a concert performance<br />

(with the orchestra spread out over the platform) <strong>of</strong> the opera he wrote for Bayreuth,<br />

where the orchestra is concealed from the audience. The principals used their scores and<br />

were, unhelpfully, relegated to two banks <strong>of</strong> seats at either side <strong>of</strong> the platform, facing in<br />

towards the conductor. This meant that they had to sing while hemmed in by the orchestra<br />

and each other, and those in the inside seats were blocked <strong>of</strong>f from sections <strong>of</strong> the<br />

audience. The <strong>of</strong>fstage horns sounded from behind the platform and Titurel and the<br />

excellent Tiffin Boys' Choir were ensconced in the side <strong>of</strong> the Balcony. It was a pity that<br />

the recorded bells sounded so artificial, and it was deeply unsatisfactory for Amfortas and<br />

Parsifal to leave the platform with unbecoming haste after they had finished singing in<br />

Act I, leaving Gurnemanz with no-one to address at the end. But even this paled beside<br />

Kundry's failure to put in an appearance at all in Act III, leaving an anonymous chorister<br />

to sing her two words. Why on earth did Gergiev allow it?<br />

All but one <strong>of</strong> the leads were already known <strong>Wagner</strong>ian quantities in the UK, having<br />

been in the 2009 Ring. The exception was Yury Vorobiev, a baby-faced bass who looked<br />

absurdly young to play the venerable, wise Gurnemanz. When he first came onto the<br />

platform, I decided that he had no right to be performing the part at his age, but when he<br />

sang, I changed my mind within seconds. This is a beautifully formed, rounded voice for<br />

which this massive role appeared to hold few terrors. He portrayed a sweet, gentle, lyrical,<br />

serene Gurnemanz, a long way removed from John Tomlinson's fierce old warrior. This is<br />

still a work in progress – he had to battle with the orchestra during the Act I narrative <strong>of</strong> the<br />

building <strong>of</strong> Monsalvat and the blessing in Act III. He still lacks a little staying power, and<br />

time will bring the voice more incisiveness. But he triumphed despite having to face<br />

obstacles encountered by few Gurnemanzes, unfairly placed furthest upstage, hemmed in<br />

by double basses and masked by his colleagues. I was also hugely impressed by his dramatic<br />

intelligence. He was the least experienced <strong>of</strong> the principals, yet it was he who could<br />

instantly create atmosphere with a look or gesture. He interacted well with his colleagues<br />

(and when Parsifal abandoned him too early in Act I, his disdainful glace at the empty chair<br />

beside him said volumes). In Act III, when he had to sing the long first section standing<br />

– 16 –

alone on the platform, he commanded it, conjuring up the absent Kundry and Parsifal with<br />

a glance or movement until the tenor belatedly appeared. This boy should go far, unless he<br />

sings heavy roles too early and too <strong>of</strong>ten. His is a voice to treasure.<br />

Larissa Gogolevskaya, who did not cover herself with glory as the<br />

Götterdämmerung Brünnhilde in 2009, proved to be far more adept as Kundry. This is<br />

unequivocally a soprano voice –“und lächte” was hair-liftingly powerful, yet the lower<br />

register is as deep and full as many Erdas I have heard. She could end a phrase with a<br />

snarl <strong>of</strong> rage (though she eschewed the customary screeches <strong>of</strong> manic laughter), yet knew<br />

the value <strong>of</strong> quietness too – the whispered “Tod” was gripping, and the single word “küss”<br />

seemed to embody all the seduction and depravity <strong>of</strong> Klingsor's realm. Given the concert<br />

format, she could do little to differentiate the character <strong>of</strong> Kundry in the different acts,<br />

but she, again, knew how a little interaction with her colleagues could go a long way –<br />

the venomous glances she exchanged with Klingsor said much, and although she did not<br />

essay the crucial kiss, the long, steady gaze which she exchanged with Parsifal conveyed<br />

volumes. So, too, did her glance around the peaceful woodland in Act I, a smile beginning<br />

to touch her lips until the harassing Esquires disturbed her peace.<br />

Nikolay Putilin, whose Alberich was one <strong>of</strong> the glories <strong>of</strong> the 2009 Ring, gave a<br />

wonderful, sharply-etched little sketch as Klingsor. He has no need to snarl or grimace to<br />

convey evil: the dark, cutting edge <strong>of</strong> his baritone does it all for him. He too was fully<br />

engaged from the very beginning – his cool, proprietorial glance about him as the prelude<br />

to Act II began established the character at once, and the way he entwined his pudgy<br />

fingers was chilling, while the orchestra boiled like a thunderstorm with evil, its<br />

sinuousness seeming almost to draw pentacles as he cast his spell to awaken Kundry. The<br />

sadness in his face, and his little, futile gesture at “hüt’ ich mir selbst den Gral” showed<br />

movingly how empty his victory would be, even if he achieved it. Like Alberich in<br />

Siegfried, Klingsor knows that he has already lost.<br />

Evgeny Nikitin's angry, leonine Amfortas was worlds away from the usual pallid<br />

invalid. Tall, strong, noble, powerfully built, this Amfortas' rage and despair was a life<br />

force that could have generated a power station and was utterly riveting. He blew the<br />

audience away. I have never heard him sing so superbly, his noble baritone wonderfully<br />

incisive. This was the angriest Amfortas I have ever seen. While he sat awaiting his cue,<br />

he blazed with energy and impatience. Unleashed, he raged against the light. Glorious.<br />

In this proud company Avgust Amonov’s Parsifal was underwhelming. He sang<br />

competently but the voice sounded colourless, and dramatically he was not the equal <strong>of</strong><br />

his colleagues. He spent most <strong>of</strong> his time hunched over his score, and if he did look up to<br />

acknowledge the presence <strong>of</strong> another singer, it was with a l<strong>of</strong>ty, disdainful “What are you<br />

doing sharing my platform?” glance which was hardly appropriate to the character.<br />

There was excellent work in all the lesser roles, especially Andrey Popov's edgy<br />

Fourth Esquire and a luscious sextet <strong>of</strong> Flowermaidens, all <strong>of</strong> whom sounded sensational<br />

and looked gorgeous in brightly coloured frocks which made them resemble a flowerbed.<br />

59 members <strong>of</strong> the Mariinsky chorus, as many as the platform could hold, created a<br />

glorious sound, especially in the wonders <strong>of</strong> the Grail scene, where the contrast between<br />

the deep, clotted bass voices and the ethereal sopranos was astonishing. The cavernous<br />

contralto voices added extra allure to the Flowermaidens' music.<br />

The emotional impact <strong>of</strong> this Parsifal was immense, worlds away from that patchy<br />

Ring. With this performance, Gergiev and his Mariinsky forces have confirmed<br />

themselves for me as major players on the international <strong>Wagner</strong> scene.<br />

– 17 –

PARSIFAL, EASTER 2012: A TOTAL IMMERSION<br />

Paul Dawson-Bowling<br />

Angela Denoke Falk Struckmann Denoke, Simon O’Neill, Kwangchul Youn<br />

Photography <strong>of</strong> the Vienna State Opera production by Michael Poehn<br />

Thanks to the generosity <strong>of</strong> my wonderful wife doing her best to provide me with a<br />

soothing balm after a family tragedy, Easter 2012 brought us several different experiences<br />

<strong>of</strong> Parsifal, the first consisting <strong>of</strong> the Mariinsky Opera’s concert in Cardiff on 31st March.<br />

This became my preferred version among four <strong>of</strong> Valery Gergiev in this work, the others<br />

being his Albert Hall performance from 1999, a Metropolitan Opera broadcast from<br />

2004, and his recent CDs recorded at St Petersburg.<br />

The St Petersburg CDs have won generous acclaim which I do not think they<br />

deserve because the performance is studio-bound and the recording variable, with string<br />

sound that <strong>of</strong>ten loses its initial opulence and thins out. The praise lavished on this version<br />

seems largely due to the “band wagon” effect. Gergiev has become immensely<br />

fashionable and whatever he does is endorsed by one critic after another, each echoing the<br />

last and keeping the band wagon rolling. The advantage <strong>of</strong> the Cardiff performance was<br />

that he was unusually involved and involving. His performance also, unsurprisingly, had<br />

something very Russian about it, something outside the mainstream traditions <strong>of</strong> Parsifal<br />

with a distinctive hue, but without the alien pronunciations and brackish vocalism which<br />

are sometimes the downside <strong>of</strong> that Russian hue.<br />

Three <strong>of</strong> the voices were magnificent, and the Amfortas <strong>of</strong> Evgeny Nikitin was<br />

exceptional in every way: rich and resonant, a musician <strong>of</strong> no mean acumen, and even in<br />

concert the most tormented and intense among all our three live encounters with<br />

Amfortas over Easter. Another singing actor <strong>of</strong> greatness was Nikolay Putilin, the<br />

Mariinsky Klingsor, a mighty bass <strong>of</strong> immense menace who froze into total stillness<br />

during the central 50 minutes <strong>of</strong> Act II before his brief appearance at the end. He then<br />

appeared to trip over an unfamiliar music stand and fell heavily, but continued both<br />

singing and menace even as he tried to save himself. A real trouper.<br />

On the concert platform without any make-up or costume to disguise his<br />

appearance, the Gurnemanz <strong>of</strong> Juri Vorobiev looked weirdly young, but his sympathetic<br />

portrayal wanted nothing in character, and for “Dein Name denn?” and for “den nun des<br />

Grales Anblick nicht mehr labte” he produced pianissimos <strong>of</strong> a delicacy uncommon since<br />

Hans Hotter sang the role. Standing next to him Avgust Amonov as Parsifal seemed very<br />

mature, and although he and the Kundry (Larisa Gorgolevskaya) were sterling artists they<br />

– 18 –

were not as spectacular as the three just singled out. Our own superlative ‘Ex Cathedra’<br />

from Birmingham joined the Russian forces to provide high sopranos <strong>of</strong> exceptional purity<br />

in the Grail Scenes and the only unsatisfactory vocal contribution came from Gergiev<br />

himself. He emoted <strong>of</strong>ten and much. It was sometimes as if he were sharing the podium<br />

with a constipated ox, snorting and bellowing at all the wrong moments. On the other hand,<br />

the sound which he drew from the orchestra had a strange, earthy fire and a tremendous<br />

technical finish which contributed to a performance <strong>of</strong> spirituality and real distinction.<br />

Our next Parsifal came six days later on Good Friday at Leipzig, and it was very<br />

poorly attended, with only about 30% <strong>of</strong> the seats occupied, in spite <strong>of</strong> seat prices – I tell<br />

no lie – one fifth <strong>of</strong> what Covent Garden charges. Apart from lower costs the big<br />

advantage <strong>of</strong> Leipzig is that it boasts a division <strong>of</strong> the Gewandhaus Orchestra in the pit,<br />

and this orchestra shares with the Dresden Staatskapelle, the Vienna Philharmonic, and<br />

the Mariinsky Orchestra the distinction <strong>of</strong> being one <strong>of</strong> the truly great, world-class<br />

orchestras whose main job is in the opera house.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> the Gewandhaus woodwind solos were staggeringly beautiful, and the<br />

sound as a whole had the body and depth which are the birthright <strong>of</strong> the great German<br />

orchestras. Ulf Schirmer, the conductor, is now not only musical director at the Leipzig<br />

Opera but has taken over from Henri Meyer as Intendant, and he demonstrated his<br />

credentials laudably, bringing out more <strong>of</strong> the score’s luminous radiance than Gergiev. He<br />

was supported not only by the phenomenal orchestra but by Roland Aeschlimann’s<br />

staging, admirably uncluttered and easy on the eye if rather blank, like an attractive<br />

pictorial representation <strong>of</strong> cyberspace.<br />

The Grail is not a chalice but a lapis exillis, a sort <strong>of</strong> philosopher’s stone fallen out<br />

<strong>of</strong> heaven, as it was in some earlier grail legends. This stone was a hologram<br />

representation, and it made a mesmerising effect as it rotated in mid-air onstage, and<br />

glided forwards out <strong>of</strong> nowhere towards the audience. There was no bread or wine, and<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the production’s more interesting but controversial features remains the closing<br />

tableau where everything else faded to leave Amfortas alone centre stage, beckoning<br />

Kundry over and enfolding her in his arms. This was not so much a passionate embrace<br />

as a loving reconciliation, agape not eros, all animosity and contempt laid to rest. Stephan<br />

Vinke (soon to be Siegfried at Covent Garden) was Parsifal as he was seven years ago,<br />

and his heroic, ringing tones had now taken on a strident edge which allowed him less<br />

inwardness than formerly.<br />

As Kundry Lioba Braun had replaced the marvellous Petra Lang, she whose<br />

picture deservedly adorned the cover <strong>of</strong> the last <strong>Wagner</strong> <strong>News</strong>, and sadly Lioba Braun was<br />

much inferior. Not only was her pallid, unsteady production no substitute for Petra Lang’s<br />

pure, golden tones, but she had neither Petra Lang’s magnetism nor the feral virulence<br />

with which Petra Lang’s Kundry rounded on the young knights attacking her in Act I.<br />

Petra Lang’s wild woman struck as much fear as hostility from these young hopefuls.<br />

The Gurnemanz <strong>of</strong> James Moellenh<strong>of</strong>f was a gentle and scholarly man, gently and<br />

musically sung, and he constantly referred to some enormous ancient book <strong>of</strong> lore and<br />

prophecy, a central feature <strong>of</strong> the production, to guide him through events. The whole<br />

performance was so good that I would energetically recommend members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Wagner</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong> to watch the internet for any more <strong>Wagner</strong> at Leipzig, and go at every opportunity.<br />

Leipzig after all was where <strong>Wagner</strong> was born, and it roused mixed emotions that the public<br />

at Leipzig are so little committed to the city’s greatest native son (Bach was not a native <strong>of</strong><br />

Leipzig but <strong>of</strong> Eisenach) that visitors can enjoy an incredible artistic bargain without even<br />

booking in advance. They can just pay at the box <strong>of</strong>fice and walk in.<br />

– 19 –

The contrast with the Vienna State Opera could not have been more extreme.<br />

There the seat prices overtopped those <strong>of</strong> Covent Garden, and to get in it at all it had been<br />

necessary to book almost a year in advance. It goes without saying that the house was sold<br />

out, and the Stehparterre, the standing room directly under the President’s Box and the<br />

best place in the house, was packed like a tin <strong>of</strong> sardines. Of course, Vienna has the<br />

Vienna Philharmonic, in my view quite simply the best in the world, no longer challenged<br />

by the Berlin Philharmonic because it has lost its incomparable Germanness and become<br />

a mechanistic collection <strong>of</strong> glacial multinationals. It was five years ago that I last heard<br />

the Vienna Philharmonic live, and my initial anxiety – had it changed? – happily went for<br />

nothing. It still possesses the same liquid radiance and lustre as I first knew long ago in<br />

1960, the same balance <strong>of</strong> ardour, power and sweetness, and such instinctive musical<br />

unanimity that the orchestra even seem to breathe together. Christian Thielemann,<br />

obviously a darling <strong>of</strong> the Viennese public, directed a flowing performance that was yet<br />

generous dynamically and expansive emotionally, except for the Act I transformation<br />

which was unexpectedly reserved. It was quite different from a broadcast from Bayreuth<br />

which I have on CD and which is more extended and magisterial.<br />

The production by Christine Mielietz was as confusing as ever. I still cannot make<br />

head or tail <strong>of</strong> the derelict ablution block where the first part <strong>of</strong> Act I is located and where<br />

Gurnemanz still spends his narrations wandering among his squad <strong>of</strong> trainee fencers<br />

correcting their moves. Nor do I understand what is meant to be happening in the second<br />

scene <strong>of</strong> Act I when the front <strong>of</strong> the stage goes up to disclose a basement full <strong>of</strong> troubled,<br />

despairing figures. The most accessible part <strong>of</strong> the staging was the Klingsor scene in Act<br />

II where Angela Denoke as Kundry was subjected to horrifying medical abuse, apparently<br />

injected with hallucinogenic substances and chemical coshes by two grim and starchy<br />

nurses, even as Klingsor sat repulsively on a red leather s<strong>of</strong>a to oversee the operation.<br />

Kwangchul Youn<br />

Michael Poehn / Wiener Staatsoper<br />

The most arresting member <strong>of</strong> the cast was<br />

Kwangchul Youn as Gurnemanz, and I was<br />

nonplussed and delighted at how beautiful, rich<br />

and steady his voice had become, nothing like<br />

those grating rinds <strong>of</strong> tone that have marked his<br />

singing lately. Falk Struckmann as Amfortas also<br />

seemed in richer and steadier voice than on his<br />

DVD <strong>of</strong> this role, <strong>of</strong> which more later. On this<br />

occasion Simon O’Neill as Parsifal sounded<br />

rather tight and hard throated, but his<br />

performance seemed convincing ins<strong>of</strong>ar as it was<br />

possible to judge it in this strange production.<br />

Angela Denoke, already mentioned as Kundry,<br />

brought a slim fine tone to the role and an<br />

inalienable musicality, so that even her screech <strong>of</strong><br />

“lachte” was really sung and not just a screech.<br />

Although the Mariinsky performances may not come again, the Leipzig and<br />

Vienna Parsifals are in the repertoire, and I particularly urge anyone who can afford the<br />

journey to Leipzig to go to Parsifal there next time round, because it is so easy and so<br />

cheap to get in.<br />

– 20 –

It is easier still to buy the DVD <strong>of</strong> the Bayreuth Parsifal from 1998, produced by<br />

Wolfgang <strong>Wagner</strong>, and conducted by Giuseppe Sinopoli on the grandest, most expansive<br />

scale. The sound and the performance <strong>of</strong> the music taken as a sound recording seem in<br />

every way superior to the two recent CD sets, one already mentioned, by Gergiev, and the<br />

other from Jaap van Zweden in Holland. This Dutch version has Klaus Florian Vogt as a<br />

silvery, sensitive Parsifal, and Robert Holl as a veteran Gurnemanz, but it is vitiated by<br />

strange balances with brass which are too distant for the climaxes. The limpid honey-flow<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Parsifal textures does not include many climaxes but the few that there are are<br />

fundamental to the architecture and really need to rock the foundations. Although the<br />

dynamic range on Sinopoli’s DVD is not as expansive as is ideal, it is wide enough to<br />

disclose the depth and quality <strong>of</strong> the performance. Sinopoli’s total belief in every last<br />

second <strong>of</strong> the score and his inner animation in every phrase lays to rest to any hint <strong>of</strong><br />

torpor, such as marred his stodgy studio Tannhäuser on DGG or Levine’s equally stodgy<br />

CDs from an earlier year <strong>of</strong> this same production.<br />

This was the production where the stage was dominated by four great blocks <strong>of</strong><br />

metallic rock, vertical and multifaceted, and it also provided a moving Grail Scene and a<br />

real Grail. Although Falk Struckmann was actually harder and more wobbly <strong>of</strong> tone on<br />

this DVD than at Vienna, he almost dominates the work in virtue <strong>of</strong> an Amfortas that is<br />

haunting in intensity, a mirror image <strong>of</strong> Christ but a failed image, but then he is equalled<br />

by Hans Sotin’s momentous Gurnemanz, more powerful and masterful even than on the<br />

Universal Classics DVD <strong>of</strong> Wolfgang <strong>Wagner</strong>’s earlier production. He also sings with real<br />

inwardness at the crucial places, and his inner humility adds to the spirituality <strong>of</strong> the<br />

whole experience. Linda Watson is a very personable Kundry, and her involvement with<br />

the role makes it easier to overlook her unsettling vibrato, and the fact that she sings<br />

slightly flat in the great scene between Kundry and Parsifal. Vocally Poul Elming as<br />

Parsifal is no John Vickers or Jess Thomas, and he looks mature in close-up shots <strong>of</strong> his<br />

face, but he sings very well in Act III, and is always pure-toned and musical. What is<br />

more important is that as a total portrayal, Elming strikes me as the best Parsifal on DVD<br />

and one <strong>of</strong> the best I have seen anywhere. He manages to convey the sense that his<br />

willowy frame contains plenty <strong>of</strong> athletic and heroic potential, and he identifies totally<br />

with the role. Indeed it possesses him. To give an idea <strong>of</strong> his quality, there is his Act II<br />

transformation from rage and revulsion at Kundry because she tries to deflect him from<br />

his mission after the big kiss from helping Amfortas into something quite different as<br />

soon as she starts to tell him her story. He looks utterly haunted by her account <strong>of</strong> her<br />

sufferings ever since her mocking <strong>of</strong> Christ on the way to his crucifixion, and Elming’s<br />

superb acting makes it plain that he is now as desperate to help her as he is to help<br />

Amfortas. He also makes it plain how he is prevented by her vituperative unwillingness<br />

to accept this help his way, the right way. Like the diabetic who insists on masses <strong>of</strong> cream<br />

and sugar instead <strong>of</strong> a sensible diet and insulin regime, she wants to do it her way, and<br />

this is utterly counter-productive.<br />

The whole experience <strong>of</strong> this DVD demonstrates how the sum is even greater than<br />

the mostly excellent parts. Even watching it at home it was the most moving and uplifting<br />

<strong>of</strong> all our Parsifal experiences over Easter, and even people who cannot afford to go to the<br />

opera at Leipzig as I recommend (let alone Vienna) can probably rise to this wonderful<br />

DVD from the C major record label. This Wolfgang <strong>Wagner</strong> production does not come at<br />

the work from a tangent, but really is a “deed <strong>of</strong> music made visible.” And is there any<br />

greater music in existence, or any greater artistic experience altogether, than Parsifal?<br />

– 21 –

WAGNER AT THE MET<br />

A multimedia presentation given by Dan Sherman on 26th April 2012<br />

Andrea Buchanan<br />

Those <strong>of</strong> us who braved the truly awful weather to hear Dan<br />

Sherman’s talk at Portland Place School were amply rewarded<br />

for our efforts. Dan gave us a fascinating, lively, amusing and<br />

extremely well-researched gallop through the Metropolitan<br />

Opera’s long involvement with the works <strong>of</strong> Richard <strong>Wagner</strong>.<br />

We were shown a wonderful variety <strong>of</strong> slides, photographs, film<br />

clips and sound recordings.<br />

We learned that the Met have staged 3,600 <strong>Wagner</strong><br />

performances to date, making up 13% <strong>of</strong> their total <strong>of</strong> opera<br />

events. Lohengrin is the most performed <strong>Wagner</strong> work (619 times), followed by Die<br />

Walküre and Tannhäuser. Der Ring has been staged in all 130 times.<br />

Dan gave a history <strong>of</strong> these performances from the 1880s to the present. He played<br />

us a very rare 1903 recording <strong>of</strong> Johanna Gadski singing Dich Teure Halle and described<br />

the glory days <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong> productions in the 1910s and 1920s featuring conductors such<br />