13895 Wagner News 174 - Wagner Society of England

13895 Wagner News 174 - Wagner Society of England

13895 Wagner News 174 - Wagner Society of England

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Lionel Friend<br />

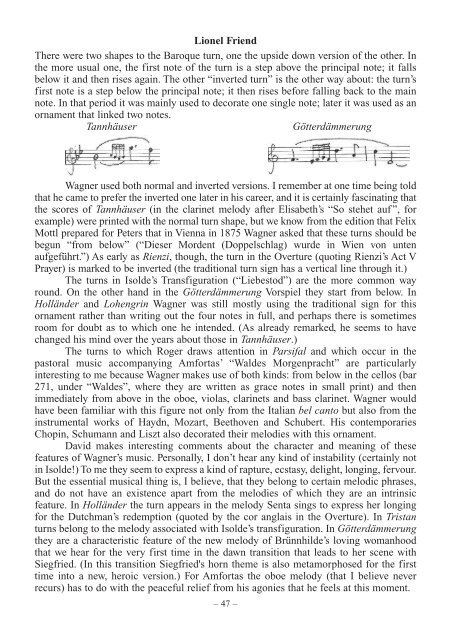

There were two shapes to the Baroque turn, one the upside down version <strong>of</strong> the other. In<br />

the more usual one, the first note <strong>of</strong> the turn is a step above the principal note; it falls<br />

below it and then rises again. The other “inverted turn” is the other way about: the turn’s<br />

first note is a step below the principal note; it then rises before falling back to the main<br />

note. In that period it was mainly used to decorate one single note; later it was used as an<br />

ornament that linked two notes.<br />

Tannhäuser Götterdämmerung<br />

<strong>Wagner</strong> used both normal and inverted versions. I remember at one time being told<br />

that he came to prefer the inverted one later in his career, and it is certainly fascinating that<br />

the scores <strong>of</strong> Tannhäuser (in the clarinet melody after Elisabeth’s “So stehet auf ”, for<br />

example) were printed with the normal turn shape, but we know from the edition that Felix<br />

Mottl prepared for Peters that in Vienna in 1875 <strong>Wagner</strong> asked that these turns should be<br />

begun “from below” (“Dieser Mordent (Doppelschlag) wurde in Wien von unten<br />

aufgeführt.”) As early as Rienzi, though, the turn in the Overture (quoting Rienzi’s Act V<br />

Prayer) is marked to be inverted (the traditional turn sign has a vertical line through it.)<br />

The turns in Isolde’s Transfiguration (“Liebestod”) are the more common way<br />

round. On the other hand in the Götterdämmerung Vorspiel they start from below. In<br />

Holländer and Lohengrin <strong>Wagner</strong> was still mostly using the traditional sign for this<br />

ornament rather than writing out the four notes in full, and perhaps there is sometimes<br />

room for doubt as to which one he intended. (As already remarked, he seems to have<br />

changed his mind over the years about those in Tannhäuser.)<br />

The turns to which Roger draws attention in Parsifal and which occur in the<br />

pastoral music accompanying Amfortas’ “Waldes Morgenpracht” are particularly<br />

interesting to me because <strong>Wagner</strong> makes use <strong>of</strong> both kinds: from below in the cellos (bar<br />

271, under “Waldes”, where they are written as grace notes in small print) and then<br />

immediately from above in the oboe, violas, clarinets and bass clarinet. <strong>Wagner</strong> would<br />

have been familiar with this figure not only from the Italian bel canto but also from the<br />

instrumental works <strong>of</strong> Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. His contemporaries<br />

Chopin, Schumann and Liszt also decorated their melodies with this ornament.<br />

David makes interesting comments about the character and meaning <strong>of</strong> these<br />

features <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wagner</strong>’s music. Personally, I don’t hear any kind <strong>of</strong> instability (certainly not<br />

in Isolde!) To me they seem to express a kind <strong>of</strong> rapture, ecstasy, delight, longing, fervour.<br />

But the essential musical thing is, I believe, that they belong to certain melodic phrases,<br />

and do not have an existence apart from the melodies <strong>of</strong> which they are an intrinsic<br />

feature. In Holländer the turn appears in the melody Senta sings to express her longing<br />

for the Dutchman’s redemption (quoted by the cor anglais in the Overture). In Tristan<br />

turns belong to the melody associated with Isolde’s transfiguration. In Götterdämmerung<br />

they are a characteristic feature <strong>of</strong> the new melody <strong>of</strong> Brünnhilde’s loving womanhood<br />

that we hear for the very first time in the dawn transition that leads to her scene with<br />

Siegfried. (In this transition Siegfried's horn theme is also metamorphosed for the first<br />

time into a new, heroic version.) For Amfortas the oboe melody (that I believe never<br />

recurs) has to do with the peaceful relief from his agonies that he feels at this moment.<br />

– 47 –