January 31, 2011 - Columbia News - Columbia University

January 31, 2011 - Columbia News - Columbia University

January 31, 2011 - Columbia News - Columbia University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FANNY<br />

SIR THOMAS<br />

Literary<br />

networking<br />

A Novel Computer Program | 3<br />

columbia ink<br />

Books by Faculty | 5<br />

Personal is<br />

political<br />

Witnessing DADT’s Repeal | 6<br />

MISS CRAWFORD<br />

EDMUND<br />

vol. 36, no. 07 NEWS and ideas FOR THE COLUMBIA COMMUNITY<br />

<strong>January</strong> <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong><br />

Looking for clues<br />

to global warming<br />

in the polar ice<br />

By Record Staff<br />

changing<br />

Climate<br />

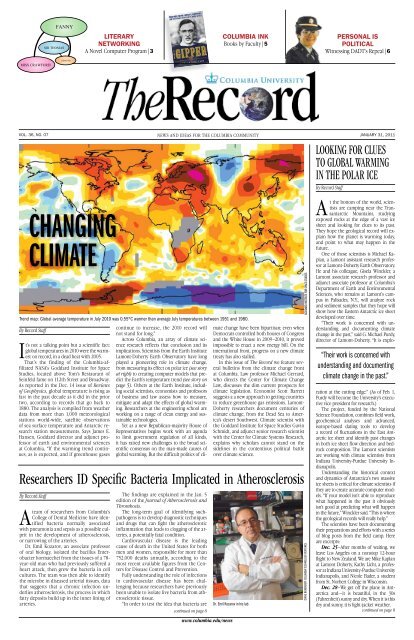

Trend map: Global average temperature in July 2010 was 0.55°C warmer than average July temperatures between 1951 and 1980.<br />

By Record Staff<br />

It’s not a talking point but a scientific fact:<br />

global temperatures in 2010 were the warmest<br />

on record, in a dead heat with 2005.<br />

That’s the finding of the <strong>Columbia</strong>-affiliated<br />

NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space<br />

Studies, located above Tom’s Restaurant of<br />

Seinfeld fame on 112th Street and Broadway.<br />

As reported in the Dec. 14 issue of Reviews<br />

of Geophysics, global temperature is rising as<br />

fast in the past decade as it did in the prior<br />

two, according to records that go back to<br />

1880. The analysis is compiled from weather<br />

data from more than 1,000 meteorological<br />

stations world-wide, satellite observations<br />

of sea surface temperature and Antarctic research<br />

station measurements. Says James E.<br />

Hansen, Goddard director and adjunct professor<br />

of earth and environmental sciences<br />

at <strong>Columbia</strong>, “If the warming trend continues,<br />

as is expected, and if greenhouse gases<br />

Researchers ID Specific Bacteria Implicated in Atherosclerosis<br />

By Record Staff<br />

Ateam of researchers from <strong>Columbia</strong>’s<br />

College of Dental Medicine have identified<br />

bacteria normally associated<br />

with pneumonia and sepsis as a possible culprit<br />

in the development of atherosclerosis,<br />

or narrowing of the arteries.<br />

Dr. Emil Kozarov, an associate professor<br />

of oral biology, isolated the bacillus Enterobacter<br />

hormaechei from the tissues of a 78-<br />

year-old man who had previously suffered a<br />

heart attack, then grew the bacteria in cell<br />

cultures. The team was then able to identify<br />

the microbe in diseased arterial tissues, data<br />

that suggests that a chronic infection underlies<br />

atherosclerosis, the process in which<br />

fatty deposits build up in the inner lining of<br />

arteries.<br />

The findings are explained in the Jan. 5<br />

edition of the Journal of Atherosclerosis and<br />

Thrombosis.<br />

The long-term goal of identifying suchpathogens<br />

is to develop diagnostic techniques<br />

and drugs that can fight the atherosclerotic<br />

inflammation that leads to clogging of the arteries,<br />

a potentially fatal condition.<br />

Cardiovascular disease is the leading<br />

cause of death in the United States for both<br />

men and women, responsible for more than<br />

752,000 deaths annually, according to the<br />

most recent available figures from the Centers<br />

for Disease Control and Prevention.<br />

Fully understanding the role of infections<br />

in cardiovascular disease has been challenging<br />

because researchers have previously<br />

been unable to isolate live bacteria from atherosclerotic<br />

tissue.<br />

“In order to test the idea that bacteria are<br />

continued on page 8<br />

continue to increase, the 2010 record will<br />

not stand for long.”<br />

Across <strong>Columbia</strong>, an array of climate science<br />

research reflects that conclusion and its<br />

implications. Scientists from the Earth Institute<br />

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory have long<br />

played a pioneering role in climate change,<br />

from measuring its effect on polar ice (see story<br />

at right) to creating computer models that predict<br />

the Earth’s temperature trend (see story on<br />

page 5). Others at the Earth Institute, including<br />

social scientists, economists and professors<br />

of business and law assess how to measure,<br />

mitigate and adapt the effects of global warming.<br />

Researchers at the engineering school are<br />

working on a range of clean energy and sustainable<br />

technologies.<br />

Yet as a new Republican-majority House of<br />

Representatives begins work with an agenda<br />

to limit government regulation of all kinds,<br />

it has raised new challenges to the broad scientific<br />

consensus on the man-made causes of<br />

global warming. But the difficult politics of climate<br />

change have been bipartisan; even when<br />

Democrats controlled both houses of Congress<br />

and the White House in 2009–2010, it proved<br />

impossible to enact a new energy bill. On the<br />

international front, progress on a new climate<br />

treaty has also stalled.<br />

In this issue of The Record we feature several<br />

bulletins from the climate change front<br />

at <strong>Columbia</strong>. Law professor Michael Gerrard,<br />

who directs the Center for Climate Change<br />

Law, discusses the dim current prospects for<br />

climate legislation. Economist Scott Barrett<br />

suggests a a new approach to getting countries<br />

to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Lamont-<br />

Doherty researchers document centuries of<br />

climate change, from the Dead Sea to America’s<br />

desert Southwest. Climate scientist with<br />

the Goddard Institute for Space Studies Gavin<br />

Schmidt, and adjunct senior research scientist<br />

with the Center for Climate Systems Research,<br />

explains why scholars cannot stand on the<br />

sidelines in the contentious political battle<br />

over climate science.<br />

Dr. Emil Kozarov in his lab<br />

Goddard Institute for Space Studies<br />

Diane Bondareff <strong>Columbia</strong> Technology Ventures<br />

“Their work is concerned with<br />

understanding and documenting<br />

climate change in the past.”<br />

At the bottom of the world, scientists<br />

are camping near the Transantarctic<br />

Mountains, studying<br />

exposed rocks at the edge of a vast ice<br />

sheet and looking for clues to its past.<br />

They hope the geological record will explain<br />

how the planet is warming today,<br />

and point to what may happen in the<br />

future.<br />

One of those scientists is Michael Kaplan,<br />

a Lamont assistant research professor<br />

at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.<br />

He and his colleague, Gisela Winckler, a<br />

Lamont associate research professor and<br />

adjunct associate professor at <strong>Columbia</strong>’s<br />

Department of Earth and Environmental<br />

Sciences, who remains at Lamont’s campus<br />

in Palisades, N.Y., will analyze rock<br />

and sediment samples that they hope will<br />

show how the Eastern Antarctic ice sheet<br />

developed over time.<br />

“Their work is concerned with understanding<br />

and documenting climate<br />

change in the past,” said G. Michael Purdy,<br />

director of Lamont-Doherty. “It is exploration<br />

at the cutting edge.” (As of Feb. 1,<br />

Purdy will become the <strong>University</strong>’s executive<br />

vice president for research.)<br />

The project, funded by the National<br />

Science Foundation, combines field work,<br />

geochemical analyses and advanced,<br />

isotope-based dating tools to develop<br />

a record of fluctuations in the East Antarctic<br />

ice sheet and identify past changes<br />

in both ice sheet flow direction and bedrock<br />

composition. The Lamont scientists<br />

are working with climate scientists from<br />

Indiana <strong>University</strong>-Purdue <strong>University</strong> Indianapolis.<br />

Understanding the historical context<br />

and dynamics of Antarctica’s two massive<br />

ice sheets is critical for climate scientists if<br />

they are to create accurate computer models.<br />

“If your model isn’t able to reproduce<br />

what happened in the past it obviously<br />

isn’t good at predicting what will happen<br />

in the future,” Winckler said. “This is where<br />

the geological records will really help.”<br />

The scientists have been documenting<br />

their preparations and efforts with a series<br />

of blog posts from the field camp. Here<br />

are excerpts:<br />

Dec. 25–After months of waiting, we<br />

leave Los Angeles on a nonstop 12-hour<br />

flight to New Zealand. We are Mike Kaplan<br />

at Lamont Doherty, Kathy Licht, a professor<br />

at Indiana <strong>University</strong>-Purdue <strong>University</strong><br />

Indianapolis, and Nicole Bader, a student<br />

from St. Norbert College in Wisconsin.<br />

Dec. 28–We get off the plane in Antarctica<br />

and—it is beautiful, in the 30s<br />

(Fahrenheit) sunny and dry. When it is this<br />

dry and sunny, it is light-jacket weather.<br />

continued on page 8<br />

www.columbia.edu/news

2 <strong>January</strong> <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong><br />

TheRecord<br />

on campUs<br />

MILESTONES<br />

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory<br />

director G. Michael Purdy<br />

was named <strong>Columbia</strong>’s executive<br />

vice president for research.<br />

Purdy, a marine geophysicist,<br />

has been Lamont’s director for<br />

10 years. Taking over as interim<br />

director of the observatory will<br />

be associate director Arthur<br />

Lerner-Lam, an expert in earthquakes who runs Lamont’s<br />

division of Seismology, Geology and Tectonophysics.<br />

Their appointments will be effective Feb. 1<br />

nicoletta barolini<br />

Morningside Joe<br />

Upstairs, researchers may be pioneering new discoveries across academic disciplines. But the big news for campus coffee lovers is that <strong>Columbia</strong> has a new café.<br />

Located on the mezzanine level of the recently opened Northwest Corner Building, Joe will be a 60-seat artisanal coffee shop that serves a full menu of espressobased<br />

drinks, drip coffee and teas. This will be the sixth Joe branch in Manhattan, but unlike its other locations near New York <strong>University</strong> and The New School, this Joe<br />

will have prepared breakfasts, lunches and snacks. And befitting its location on a university campus, Joe will offer coffee classes, including lessons on home brewing<br />

techniques and milk steaming. Joe is open to the public Monday through Friday, 8:00 am. to 8:00 p.m., and on weekends from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.<br />

USPS 090-710 ISSN 0747-4504<br />

Vol. 36, No. 07, <strong>January</strong> <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong><br />

Published by the<br />

Office of Communications and<br />

Public Affairs<br />

David M. Stone<br />

Executive Vice President<br />

for Communications<br />

TheRecord Staff:<br />

Editor: Bridget O’Brian<br />

Designer: Nicoletta Barolini<br />

Senior Writer: Melanie A. Farmer<br />

<strong>University</strong> Photographer: Eileen Barroso<br />

Contact The Record:<br />

t: 212-854-2391<br />

f: 212-678-4817<br />

e: curecord@columbia.edu<br />

The Record is published every three weeks<br />

between September and June.<br />

Correspondence/Subscriptions<br />

Anyone may subscribe to The Record for $27<br />

per year. The amount is payable in advance to<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>University</strong>, at the address below. Allow<br />

6 to 8 weeks for address changes.<br />

Postmaster/Address Changes<br />

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY and<br />

additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send<br />

address changes to The Record, 535 W. 116th<br />

St., 402 Low Library, Mail Code 4321, New<br />

York, NY 10027.<br />

Happening at<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong><br />

For the latest on upcoming <strong>Columbia</strong> events,<br />

performances, seminars and lectures, go to<br />

calendar.columbia.edu<br />

Space Oddity<br />

Dear Alma,<br />

Virtually every story about the NASA<br />

Goddard Institute of Space Studies, including<br />

ours, mentions that its office is<br />

above Tom’s Restaurant, the iconic diner<br />

featured prominently in Seinfeld. Why is<br />

a unit of NASA there<br />

—Goddard Fan<br />

Dear Fan<br />

The Institute was founded in 1961 as<br />

a laboratory of the Goddard Space Flight<br />

Center’s Earth Sciences Division. It was<br />

established by Robert Jastrow, (CC’44,<br />

GSAS’45, PhD’48), a NASA scientist whose<br />

many years at <strong>Columbia</strong> probably factored<br />

into in the institute’s location here.<br />

Jastrow was Goddard’s first director and<br />

a professor of geophysics at <strong>Columbia</strong>.<br />

(Graduates of the College and of Barnard<br />

may recall taking “Astro-Jastrow” for their<br />

undergraduate science requirement.)<br />

In its earliest days, the Goddard Institute<br />

was located in the Interchurch<br />

Tom’s Restaurant is located on the corner of 112th<br />

Street and Broadway.<br />

Center on Riverside Drive. But in 1965,<br />

as the <strong>University</strong> expanded its real estate<br />

holdings in Morningside Heights, <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

bought the building on the corner of<br />

112th Street and Broadway.<br />

The seven-story apartment building<br />

was built in 1900 as speculative real estate<br />

development swept the Upper West<br />

Side with the new IRT subway line. It was<br />

converted into a 197-unit single room<br />

occupancy hotel in 1946. When <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

bought the building, it renovated it<br />

ASK ALMA’S OWL<br />

into offices and renamed it Armstrong<br />

Hall for Edwin H. Armstrong (ENG’13,<br />

HON’29), the <strong>Columbia</strong> professor of<br />

electrical engineering whose work made<br />

FM radio possible. Goddard moved thre<br />

when it opened.<br />

Much of Goddard’s early work involved<br />

study of planetary atmospheres<br />

using data collected by telescopes and<br />

space probes, its website says. It naturally<br />

followed, then, that Goddard became a<br />

center of atmospheric modeling and climate<br />

change.<br />

The affiliation between the institute<br />

and the <strong>University</strong> started informally in<br />

1961, as “an arrangement in which it was<br />

envisioned that many of the research<br />

staff would be <strong>Columbia</strong> researchers,”<br />

said Larry Travis, Goddard’s current deputy<br />

director.<br />

Since then, more ties were added.<br />

Some also are <strong>Columbia</strong> adjunct professors,<br />

and all Goddard researchers can act<br />

as advisers to graduate students in such<br />

disciplines as applied physics, math and<br />

astronomy. In 1994, in order to enhance<br />

interdisciplinary research work on climate<br />

and earth systems, <strong>Columbia</strong> and<br />

Goddard jointly established the Center<br />

for Climate Systems Research. It is a unit<br />

of the Earth Institute.<br />

— Bridget O’Brian<br />

Send your questions for Alma’s Owl to<br />

curecord@columbia.edu.<br />

Fred Van Sickle has been<br />

named executive vice president<br />

for university development and<br />

alumni relations, effective Jan. 1.<br />

Van Sickle, who joined <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

in 2002, formerly served as vice<br />

president for university development<br />

under his predecessor, Susan<br />

Feagin (GS’74). Feagin will<br />

remain at the <strong>University</strong> as a special advisor to President<br />

Lee C. Bollinger and plans to work on projects related<br />

to alumni relations and development. Feagin and Van<br />

Sickle spearheaded The <strong>Columbia</strong> Campaign, which is<br />

expected to exceed its original $4 billion goal for new<br />

gifts and pledges nearly a year ahead of schedule. Building<br />

on this momentum, the <strong>University</strong> recently raised<br />

its goal to $5 billion by the end of 2013.<br />

Assaf Zeevi, the Henry Kravis<br />

Professor of Business at the<br />

Graduate School of Business,<br />

has been named vice dean for<br />

research, effective July 1. Zeevi,<br />

who specializes in decision,<br />

risk and operations, joined the<br />

school as an assistant professor<br />

in 2001 and was awarded the Dean’s Prize for Teaching<br />

Excellence in 2003. He succeeds Gita Johar, the Meyer<br />

Feldberg Professor of Business, who will become senior<br />

vice dean in charge of faculty recruitment, retention<br />

and development.<br />

John S. Micgiel, associate director of the Harriman Institute<br />

and director of the East Central European Center,<br />

was awarded a medal by the Institute of National<br />

Remembrance in Warsaw, Poland, last month. Micgiel<br />

was honored for his contributions toward a greater understanding<br />

of the history of modern Poland.<br />

grants & gifts<br />

WHO GAVE IT: Thomas Cornacchia (CC’85) and<br />

Goldman Sachs Gives<br />

HOW MUCH: $1 million<br />

WHO GOT IT: Department of Athletics<br />

WHAT FOR: To establish an endowment in support<br />

of the men’s heavyweight, men’s lightweight and<br />

women’s rowing programs.<br />

WHO GAVE IT: OneMarketData LLC<br />

HOW MUCH: $800,000 (in kind)<br />

WHO GOT IT: <strong>Columbia</strong> Business School<br />

WHAT FOR: The company’s donation of OneTick<br />

software, a proprietary data management tool,<br />

will be used to process market data and streamline<br />

research in structure, trading and market<br />

making.<br />

WHO GAVE IT: Estate of Louis Lowenstein Jr.<br />

(CC’47, L’53)<br />

HOW MUCH: $500,000<br />

WHO GOT IT: <strong>Columbia</strong> Law School<br />

WHAT FOR: Before his death in 2009, Lowenstein,<br />

a professor of law for nearly three decades, established<br />

the Lou and Helen Lowenstein Loan<br />

Repayment Assistance Fellowship, which helps<br />

selected graduates who pursue a career in public<br />

interest law. This gift will further support that<br />

fellowship.<br />

WHO GAVE IT: Peter Klein ’77GSAS, ’87GSAS, and<br />

Catherine Klein<br />

HOW MUCH: $100,000<br />

WHO GOT IT: Graduate School of Arts and Sciences<br />

WHAT FOR: This gift in support of student fellowships<br />

in mathematics will be doubled under the<br />

terms of the GSAS Fellowship Match.

TheRecord <strong>January</strong> <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong> 3<br />

Social Networking in the Age of Austen, Trollope and Dickens<br />

By Nick Obourn<br />

Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet on Facebook With<br />

social networking the hot topic of the day, a computer<br />

science grad student, his advisor and a literature<br />

professor teamed up to analyze social interactions in<br />

19th century British novels.<br />

David Elson, a Ph.D. candidate in computational linguistics<br />

and a longtime film buff, has long been interested in the intersection<br />

of narrative and computers.<br />

“I started thinking about how storytelling works as a language,<br />

with a syntax that we pick up as children and that differs<br />

from culture to culture,” says Elson. “We are starting to be<br />

able to write programs that can learn a language by reading<br />

a lot of it—why can’t a program learn the meanings of stories<br />

the same way”<br />

This line of thinking led Elson, who is part of the Natural<br />

Language Processing Group in the computer science department<br />

at the engineering school, to create a computer program<br />

in 2009 that could “read” for dialogue in digitally scanned<br />

novels and create social networking maps.<br />

Diagrams of the social networks resemble connected<br />

thought bubbles, where the size of the bubble denotes the<br />

amount of dialogue spoken by a particular character. “Work<br />

in this field—digital humanities—focused on the word level—how<br />

often a single word appears over the centuries, for<br />

example,” says Elson. “I wanted to look more broadly at social<br />

interaction that takes place through quoted speech.”<br />

Elson and his advisor, Kathleen McKeown, the Henry and<br />

Gertrude Rothschild Professor of Computer Science, knew they<br />

needed help from a literature professor to see if the program<br />

worked. With a little social networking of their own, they enlisted<br />

Nicholas Dames, Theodore Kahan Associate Professor in<br />

the Humanities, an expert in the Victorian era.<br />

Luckily, 19th century literature proved to be perfect for the<br />

project since large numbers of books from the period are out<br />

of copyright and have been digitized. “For a literary scholar,<br />

it’s like a room full of new toys to play with, and no one ‘owns’<br />

those toys,” says Dames. “Then the question is: What are we<br />

going to do with these things”<br />

The answer was to use Elson’s program to try to analyze a<br />

longstanding literary theory that Victorian<br />

novels set in the city have more characters,<br />

looser social networks and less dialogue<br />

than those with country settings.<br />

Dames cites the work of Raymond Williams,<br />

a Welsh-born Cambridge <strong>University</strong> literature<br />

professor who pioneered the idea. “He developed<br />

a series of extremely persuasive arguments<br />

about how, in the 19th century, novelists began<br />

to imagine urban social interaction as fundamentally<br />

different—more dispersed, accidental and<br />

fleeting—than the kinds of social interactions<br />

found in village or rural settings,” says Dames.<br />

“His arguments were based on very elegant readings<br />

of a select few authors—most notably Austen<br />

and Dickens—and they quickly became fairly<br />

standard, canonical theories.”<br />

In contrast, the team worked with 60 19th<br />

century novels, totaling more than 10 million<br />

words. The list included books by Charles Dickens,<br />

Jane Austen, Charlotte and Emily Brontë,<br />

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, George Eliot, Anthony<br />

Trollope and Thomas Hardy.<br />

Contrary to Williams’ hypothesis, the<br />

analysis found that social networks in rural<br />

and urban setting were about the<br />

same size and had the same levels<br />

of interaction. This past summer,<br />

MR.<br />

RUSHWORTH<br />

the team presented their findings<br />

at the annual conference of the<br />

Association for Computational<br />

Linguistics in Uppsala, Sweden,<br />

where it received the award for<br />

best student paper.<br />

Heartened by the positive response,<br />

they have decided to expand their efforts and graph how social<br />

networks change in novels as the plot unfolds. This would<br />

be “a way of thinking about how plot generates or retards or<br />

shapes social connections,” says Dames.<br />

Elson, who has a job lined up at Google after he graduates<br />

in May, is very interested in the potential of bridging literature<br />

and technology.<br />

SUSAN<br />

WILLIAM<br />

DR.GRANT<br />

MRS.<br />

GRANT<br />

MRS.<br />

RUSHWORTH<br />

MISS CRAWFORD<br />

SIR THOMAS<br />

FANNY<br />

EDMUND<br />

MRS.<br />

NORRIS<br />

MARIA<br />

JULIA<br />

TOM<br />

MR.YATES<br />

A diagram of<br />

social networking<br />

in Jane Austen’s<br />

Mansfield Park created<br />

by software developed by David<br />

Elson, a Ph.D. candidate in computational linguistics who is<br />

interested in using technology to shed light on narrative.<br />

“We’ll soon be able to trace the spread of ideas from culture<br />

to culture and put common assumptions about our heritage to<br />

the test,” he says. “We’re not losing the close read—we’re gaining<br />

the power to instantly get a sense of where a text or an idea<br />

fits in the big picture. We’re just starting to peek at what will be<br />

a new expanse of scholarship possibilities.”<br />

On Exhibit :<br />

Barnard Hosts First Women’s Film Festival<br />

Bloomberg Visits Campus to Launch New Center<br />

Devoted to Green Building Technology<br />

Twelve features and documentaries by<br />

and about women will be screened at<br />

the first Athena Film Festival on the Barnard<br />

campus Feb. 10-13. The lineup includes<br />

Miss Representation, a film that explores<br />

the media’s disparaging portrayals of<br />

women; Desert Flower, the best-selling story<br />

of a Somali refugee-turned-model; and<br />

Mo, a portrait of the charismatic Northern<br />

Ireland political figure Mo Mowlam.<br />

Kathryn Kolbert, director of Barnard’s<br />

Athena Center for Leadership Studies,<br />

launched the festival with Melissa Silverstein,<br />

founder of Women and Hollywood,<br />

to showcase women’s contributions to<br />

the industry. The festival will honor leading<br />

industry figures in a ceremony Feb. 10.<br />

Recipients of the Athena Awards include<br />

Delia Ephron (BC’66) (You’ve Got Mail),<br />

Chris Hegedus (The War Room) and Debra<br />

Granik and Anne Rosellini, director and cowriters<br />

of Winter’s Bone.<br />

One short may be of particular interest<br />

to the Barnard community: Growing Up Barnard,<br />

directed by Daniella Kahane (BC’05),<br />

who counts four generations of Barnard<br />

alums in her family. The film explores the<br />

relevance of women’s colleges today and<br />

features interviews with Anna Quindlen<br />

(BC’74) and Suzanne Vega (BC’81).<br />

—Ann Levin<br />

Pictured from left, <strong>University</strong> senior executive vice president Robert Kasdin; Economic Development Corp. president Seth W. Pinsky; Trinity Real Estate president Jason Pizer; IBM<br />

researcher Jane Snowdon; Bloomberg; CUNY vice chancellor for research Gillian Small; and SEAS dean Feniosky Peña-Mora.<br />

By Record Staff<br />

Just weeks after <strong>Columbia</strong> officially opened the<br />

Northwest Corner Building, Mayor Michael R.<br />

Bloomberg used the building’s dramatic atrium<br />

as the backdrop for announcing a new center devoted<br />

to green building technology—part of his plan<br />

to create a sustainable future for the city.<br />

The NYC Urban Technology Innovation Center<br />

was established to promote the development and<br />

commercialization of green building technologies<br />

in New York City. It was developed through a partnership<br />

between the Fu Foundation<br />

School of Engineering and<br />

Applied Science; Polytechnic Institute<br />

of New York <strong>University</strong>;<br />

the city’s Economic Development<br />

Corporation and City <strong>University</strong> of<br />

New York (CUNY).<br />

“By bringing together New<br />

York City’s business innovators,<br />

academics and building owners, the NYC Urban<br />

Technology Innovation Center will capitalize on<br />

some of our city’s greatest strengths, creating jobs<br />

and helping realize our vision of a greener, greater<br />

New York,” Bloomberg said at the Jan. 20 event.<br />

On Earth Day 2007, Bloomberg announced<br />

PlaNYC 2030, his comprehensive sustainability plan<br />

that seeks to reduce the city’s greenhouse gas emissions<br />

while accommodating a population growth of<br />

For video of the center’s launch event, go to<br />

news.columbia.edu/urbantechcenter<br />

nearly 1 million over the next quarter century.<br />

The center has the potential to help the city<br />

achieve its goals by funneling the latest scientific<br />

research into sustainable building technology to<br />

companies that are making green products and<br />

real estate developers who are willing to use them.<br />

In addition, it will serve as a clearinghouse for information<br />

about the costs and benefits of the new<br />

technology.<br />

The center “will promote building efficiency,” said<br />

Senior Associate Dean Jack McGourty, executive director<br />

of the center, which will be managed by the<br />

Engineering School’s Center for<br />

Technology, Innovation and Community<br />

Engagement. “This not only<br />

will be vital in reducing the city’s<br />

overall carbon footprint, but also<br />

will promote economic growth.”<br />

Speaking at the event, Robert<br />

Kasdin, senior executive vice<br />

president of the <strong>University</strong>, said<br />

the Bloomberg administration recognized the importance<br />

of scientific knowledge and technological<br />

innovation in creating a vibrant urban economy.<br />

“New York always has been a place of big ideas,<br />

many of them fueled by our great colleges and universities,”<br />

he said. “<strong>Columbia</strong> always has taken its<br />

identity from being both in and of the city of New<br />

York. Today is a day to celebrate that bond and<br />

what it will mean for New York’s future.”

4 january <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong><br />

TheRecord january <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong><br />

TheRecord<br />

Climate research<br />

Scientists Drill For Insights Under the Salty Dead Sea<br />

By David Funkhouser<br />

Scientists are drilling deep into the bed of the fast-shrinking<br />

Dead Sea, searching for clues to past climate changes<br />

and other events that may have affected human history<br />

even earlier than biblical times. They have found that the sea<br />

has come and gone in the past—a revelation with powerful<br />

implications for the current Mideast.<br />

Bordering Israel and Jordan, the inland Dead Sea is Earth’s<br />

lowest-lying spot on land, with shores some 1,400 feet below<br />

ocean level and hyper-salty waters going down another 1,200<br />

feet or more. Beneath it lie deep deposits of salts and sediments<br />

fed mainly by Jordan River drainage.<br />

The drilling is being conducted<br />

by investigators from Israel, the<br />

United States, Germany, Japan,<br />

Norway and Switzerland.<br />

Steven L. Goldstein, professor<br />

of Earth and Environmental<br />

Sciences and a geochemist at<br />

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory,<br />

one of the project leaders,<br />

says that drill cores show that<br />

the Dead Sea has dried up at least<br />

twice without human intervention<br />

over hundreds of thousands of years. “Climate models predict a<br />

greater aridity with a warmer climate,” he noted. “Just imagine<br />

what this means if a warming climate results in the present day<br />

fresh water supply becoming scarcer and scarcer.”<br />

Scarce fresh water is an explosive issue in this part of the<br />

world; the Dead Sea has been shrinking rapidly as Syria, Israel,<br />

Jordan and the Palestinian Authority pull virtually all the<br />

water from the Jordan River for agriculture and other uses. At<br />

its southern end also lie huge evaporation ponds, where Israel<br />

and Jordan mine salt. If changing climate further dries<br />

the region, pressure on the fresh water supply will increase.<br />

Previous research along the Dead Sea’s shores determined<br />

that water levels fluctuated with the coming and going of ice<br />

ages over the last several hundred thousand years. Surrounding<br />

bluffs show higher shorelines; the current sea is more than<br />

800 feet lower than it was during the height of the last glaciation<br />

some 20,000 years ago.<br />

The main drill site is the deepest part of the sea, in about<br />

1,000 feet of water 5 miles off the Israeli shore. Drilling began<br />

Nov. 21 and continued through mid-<strong>January</strong> when it was suspended<br />

for maintenance and repair. It is scheduled to resume<br />

in March. The International Continental Scientific Drilling<br />

Program is sponsoring the project and covering roughly 40<br />

“This is looking at climate<br />

at a very important place<br />

in human history.”<br />

percent of the $2.5 million cost. The remaining funds come<br />

from funding agencies in Israel and the other participating<br />

countries, including the National Science Foundation in the<br />

United States.<br />

Minerals that settle to the bottom of the Dead Sea during<br />

annual dry seasons contain uranium that allows researchers to<br />

date the sediment layers; dry season minerals alternate with layers<br />

of mud formed during the wet seasons. From these deposits,<br />

researchers can find evidence of water chemistry, prevailing<br />

winds and changing climate, not only year by year, but season<br />

by season. At two points, the researchers have already come<br />

across levels composed of pebbles, indicating that the middle<br />

of the Dead Sea was once a beach. These events could coincide<br />

with the end of the last glacial<br />

period around 13,000 to 14,000<br />

years ago, and an earlier interglacial<br />

period 125,000 years ago.<br />

Other levels show evidence<br />

of earthquakes, as layers of sediment<br />

that normally lie flat are<br />

twisted into convoluted shapes.<br />

With precise dating, these should<br />

form a detailed picture of the ancient<br />

history of earthquakes in<br />

the region. “An earthquake was<br />

almost certainly the source of<br />

the biblical story of Jericho, when the walls came tumbling<br />

down,” Goldstein says.<br />

Information from the sediments could form valuable context<br />

for that and other ancient stories. The region is thought<br />

to have been the corridor for various human migrations, and<br />

is the primary route by which early people spread out from<br />

Africa. “This is looking at climate at a very important place in<br />

human history,” Goldstein said.<br />

The chief Israeli scientists on the project are Mordechai<br />

Stein of the Geological Survey of Israel and Zvi Ben-Avraham<br />

of Tel Aviv <strong>University</strong>; others come from the German Research<br />

Center for Geosciences (GFZ), the Hebrew <strong>University</strong> of Jerusalem,<br />

the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in<br />

Zurich, the <strong>University</strong> of Geneva, the International Research<br />

Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto and the <strong>University</strong> of<br />

Minnesota. The group is hoping to involve scientists from the<br />

Palestinian territories and Jordan as well.<br />

The team hopes to recover cores of sediment going as far<br />

back in time as possible, up to several hundred thousand<br />

years ago.<br />

David Funkhouser is a science writer at Lamont-Doherty Earth<br />

Observatory<br />

Above: Sediment cores taken from the Dead Sea indicate the area has dried up at least twice<br />

without human intervention. The lake faces new stress now from humans pulling fresh water<br />

from the Jordan River, which flows into the sea.<br />

Geology Professor Steven Goldstein stands on a drilling rig in the Dead Sea last November<br />

with a core sample taken from deep below the salty sea between Jordan and Israel.<br />

Goldstein is part of a team of researchers drilling to discover clues to past climate change<br />

and natural disasters in the region.<br />

Adi Torfstein<br />

Adi Torfstein<br />

Law School’s Gerrard Sees Little Hope for Climate Bill This Year<br />

By Bridget O’Brian<br />

Now that Republicans have taken control of the<br />

House of Representatives, a leading expert on climate<br />

change law is not optimistic about the<br />

prospects for meaningful climate legislation in the next<br />

two years.<br />

“The best we can hope for from this Congress is some<br />

energy legislation that would encourage renewable energy<br />

and efficiency”—and even that isn’t a sure thing, says Michael<br />

Gerrard (CC’72), director of <strong>Columbia</strong> Law School’s<br />

Center for Climate Change Law.<br />

The center, which was started in 2009, develops legal<br />

techniques to fight climate change, trains law students and<br />

lawyers in their use, and serves as a clearinghouse for information<br />

about the issue. Gerrard was an environmental<br />

lawyer for 30 years, most recently at the law firm Arnold<br />

& Porter, before becoming the Andrew Sabin Professor of<br />

1<br />

Professional Practice at the law school; he also holds an appointment<br />

at the Earth Institute.<br />

He sees the fight over climate change focusing on the<br />

regulatory authority of the Environmental Protection Agency,<br />

with Congress attempting to suspend or revoke it or<br />

simply to freeze the agency’s funding. Republicans have<br />

already introduced legislation to block the E.P.A.’s ability to<br />

regulate greenhouse gases.<br />

The U.S. Supreme Court held in 2007 that the Clean Air<br />

Act grants the agency the authority to regulate heat-trapping<br />

auto emissions. It was, at the time, a big win for environmentalists.<br />

This year, Gerrard and other climate change<br />

advocates are awaiting the outcome of a case the Supreme<br />

Court recently agreed to hear, Connecticut vs. American<br />

Electric Power.<br />

It was brought by eight states seeking to force five utilities<br />

to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions on the theory<br />

3<br />

20<br />

10<br />

10<br />

21<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1 2 4<br />

1<br />

4 7<br />

1 1 1 2 1 2 1 0<br />

Source: Arnold & Porter and <strong>Columbia</strong> Center for Climate Change Law<br />

Number of Cases<br />

130<br />

120<br />

110<br />

100<br />

Climate Litigation: Filings<br />

Other<br />

Common Law<br />

National Environmental Policy Act<br />

Coal<br />

Industry<br />

Environmentalist<br />

12 9<br />

4 6<br />

1989 1992 1993 1996 1997 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

A chart shows how lawsuits related to climate change have skyrocketed in recent<br />

years, with the majority filed by industry seeking to overturn EPA rules<br />

1<br />

3<br />

10<br />

22<br />

Year Filed<br />

3<br />

1<br />

14<br />

32<br />

4<br />

22<br />

15<br />

4 9<br />

8<br />

9<br />

13<br />

96<br />

( 372 c a s e s a s o f<br />

J a n . 5 , <strong>2011</strong> )<br />

that they are a public nuisance. In 2009, the 2nd U.S. Circuit<br />

Court of Appeals court ruled in favor of the states. This theory<br />

could open up liability claims against not only electric<br />

utilities, but also a broad swath of industries.<br />

It could be the Court’s most important environmental<br />

decision since the 2007 case, Massachusetts v. EPA.<br />

“This will be very big,” Gerrard says. “We know the<br />

four justices who dissented in that case would want to<br />

reverse this current case.” He was referring to Chief Justice<br />

John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence<br />

Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr.<br />

The outcome of the Connecticut case is uncertain in part<br />

because Justice Sonia Sotomayor has recused herself due to<br />

her involvement in the case at the appellate level, and a 4-4<br />

tie is possible.<br />

Gerrard notes that in addition to the Supreme Court action,<br />

lawsuits related to climate change have skyrocketed.<br />

According to the database of the Center for Climate Change<br />

Law, 132 lawsuits were filed in U.S. courts in 2010 compared<br />

to 54 in 2009. The majority, 96, were filed by industry firms<br />

seeking to overturn the E.P.A.’s regulations concerning<br />

greenhouse gas emissions. Just a handful were filed by environmentalists.<br />

“Coal-fired plants are the largest single source of greenhouse<br />

gases in the United States so the environmental community<br />

has launched a campaign to stop the construction<br />

of any new coal plants, and it’s been very successful so far,”<br />

Gerrard says.<br />

Unlike tax or bankruptcy law, there isn’t one statute governing<br />

climate change, nor are there specific laws on the<br />

books as yet to address climate change.<br />

Those difficulties stem from the very nature of climate<br />

change. “It involves a broad range of human activities that<br />

have a cumulative impact over time and over space all over<br />

the world,” says Gerrard.<br />

“Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in any one location<br />

will not have a local or immediate effect, but it will contribute<br />

overall to the eventual solution of the problem.”<br />

Advocates for climate change legislation have their work<br />

cut out for them over the next couple years as they contend<br />

with a new crop of lawmakers hostile to the idea of regulating<br />

emissions. In addition to introducing anti-regulatory<br />

bills, House climate change skeptics are expected to launch<br />

investigations challenging scientific research on the topic.<br />

“The 2012 election could bring a whole new ball game,”<br />

says Gerrard. “It could get better, it could get worse.”

Climate research<br />

Using Game Theory to Forecast Climate Trends<br />

By Melanie A. Farmer<br />

Economist Scott Barrett is no fan<br />

of the Kyoto Protocol, the international<br />

agreement to reduce greenhouse<br />

gas emissions and get climate<br />

change under control. Barrett proposes<br />

a different approach: tackle the gigantic<br />

problem, one piece at a time.<br />

“If we break up the problem into<br />

smaller pieces we’re more likely to have a<br />

dramatic impact in the end,” he says.<br />

Lamont-Doherty Researcher: Southwest<br />

Headed for Permanent Drought<br />

By David Funkhouser<br />

The American Southwest has seen naturally induced dry<br />

spells throughout the past, but now human-induced<br />

global warming could push the region into a permanent<br />

drought in the coming decades, according to Lamont-Doherty<br />

scientist Richard Seager and others who have been studying the<br />

area’s climate.<br />

Seager, who focuses on climate variability and climate<br />

change, began his work studying<br />

droughts by looking into<br />

the past using sea surface<br />

temperature records gathered<br />

by ships plying the oceans in<br />

the 19th century. He and colleagues<br />

used computer models<br />

to recreate a climate history<br />

that showed periodic droughts.<br />

Focusing on North America,<br />

they also used tree rings to<br />

look back as far as the Middle<br />

Ages, when the Southwest experienced<br />

a drought lasting<br />

hundreds of years.<br />

“You begin to see that there’s<br />

a natural cycle of droughts,<br />

large and small,” says Seager,<br />

the Palisades Geophysical Institute/Lamont research professor<br />

at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “But when you add<br />

in the human effects from rising greenhouse gases, we could<br />

be pushing subtropical regions like the American Southwest<br />

into a permanent state of aridity. There are signs it’s already<br />

underway.”<br />

In a 2007 paper, Seager and colleagues used computer<br />

models to show the Southwest is on the verge of a transition<br />

to a more arid climate. And in the December 2010 issue of<br />

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Seager and<br />

Gabriel Vecchi of NOAA pinned the drying to a drop in winter<br />

Barrett, the Lenfest-Earth Institute<br />

Professor of Natural Resource Economics<br />

with a joint appointment in the School of<br />

International and Public Affairs and the<br />

Earth Institute, is an expert in complex<br />

international negotiations.<br />

He uses game theory, which analyzes<br />

how people make decisions when the<br />

desired outcome depends on the choices<br />

of other people, to understand how<br />

treaties such as Kyoto can get countries<br />

to behave differently. He has advised a<br />

number of international organizations,<br />

including the United Nations and the<br />

World Bank, on health, climate and other<br />

global issues.<br />

The Kyoto Protocol sets binding targets<br />

for 37 industrialized countries to reduce<br />

six greenhouse gases; those targets<br />

are set to expire next year. The United<br />

States is not a party. Barrett suggests it<br />

would be more productive if more agreements<br />

were negotiated focusing on individual<br />

gases and sectors—and in fact,<br />

such proposals are already on the table.<br />

For example, the United States,<br />

Mexico and Canada have expressed<br />

their willingness to reduce hydrofluorocarbons<br />

or HFCs, which are used as<br />

refrigerants in air conditioners and<br />

cooling systems, under an existing<br />

treaty, the Montreal Protocol. HFCs are<br />

one of the six greenhouse gases in the<br />

Kyoto agreement.<br />

The Montreal Protocol was adopted<br />

“If we break up the problem into smaller<br />

pieces we’re more likely to have a<br />

dramatic impact in the end.”<br />

in 1987 to phase out chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons<br />

found in aerosol cans<br />

that were destroying the ozone layer. It<br />

is considered one of the most<br />

successful international<br />

agreements.<br />

Barrett credits its success<br />

to its ingenious design,<br />

which incorporates<br />

carrot-and-stick incentives.<br />

The main “carrot”<br />

or reward is a payment<br />

to compensate developing<br />

countries for the additional<br />

costs of phasing out CFCs. The<br />

main “stick” is the threat to restrict<br />

trade to punish countries<br />

that are not party to the treaty.<br />

Barrett says these incentives<br />

could control HFCs effectively,<br />

but would not work if applied<br />

across the board to reductions<br />

TheRecord <strong>January</strong> january <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong> <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong> 5<br />

in the main greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide<br />

(CO2), because they might spark<br />

a trade war. For instance, there would<br />

be a political uproar, and possible trade<br />

retaliation, if countries in the European<br />

Union and Japan restricted trade against<br />

the U.S. for not ratifying Kyoto.<br />

Rather, he believes CO2 emissions are<br />

best limited by focusing on individual<br />

sectors such as steel, aluminum, automobiles<br />

or electricity.<br />

“The logic is partly that you can use<br />

the leverage you have for each piece<br />

to bring about the greatest amount of<br />

change,” Barrett says. “When you throw<br />

everything together—like what’s being<br />

done in the Kyoto Protocol—you lose<br />

that leverage.”<br />

Barrett notes that the key problem<br />

with the Kyoto Protocol is that it has no<br />

meaningful enforcement mechanism.<br />

“This whole approach can only succeed<br />

if you can enforce what countries agree<br />

to do,” he says. “We’ve been unable to<br />

figure out how to do that.”<br />

As far as he’s concerned, it’s<br />

time for a new approach. “There<br />

are no silver bullets,” he says<br />

about his piecemeal strategy,<br />

“but this approach is better<br />

than Kyoto. Fortunately, the<br />

failure of the Copenhagen<br />

negotiations is causing people<br />

to be open to new proposals.<br />

I think we’re there<br />

now.” In 2009, international<br />

delegates to<br />

a climate summit<br />

in the Danish<br />

capital failed to<br />

agree on binding<br />

Scott Barrett is an expert in complex<br />

international negotiations.<br />

action to curb<br />

greenhouse gas<br />

emissions.<br />

precipitation and showed how this is caused by changes in<br />

atmospheric circulation and water vapor transports induced<br />

by warming temperatures.<br />

The warming also shortens the snow season, reduces<br />

the snow mass that serves as natural storage for water, and<br />

forces an earlier spring melt, disrupting the supply system<br />

that waters much of the Southwest—the region from the<br />

western Great Plains to the Pacific, and the Oregon border<br />

to southern Mexico.<br />

That is ominous news for a region that has seen explosive<br />

growth in population, land use<br />

and water demands in recent<br />

decades. A reduction in the flow<br />

of important water resources<br />

such as the Colorado River will<br />

have serious consequences.<br />

“I’m curious how the Southwest<br />

is going to handle this,”<br />

Seager says.<br />

He says the natural variations<br />

between wet and dry periods<br />

are driven mostly by the<br />

El Niño/La Niña cycle of sea<br />

surface warming and cooling<br />

in the Pacific. “The anthropo-<br />

Aerial view of Lake Powell in Arizona. The prominent white rings surrounding the edges genic signal is currently small<br />

of the cliffs are due to steadily receding water levels.<br />

compared to the natural variability,”<br />

Seager says. “But you<br />

can see it, and it’s consistent with the climate models. It<br />

works across the whole subtropics. Right now the human<br />

effect is small, but it will become a serious problem in the<br />

decades down the road.”<br />

Local water system managers want to know how much<br />

water will be available in coming years, but Seager can’t offer<br />

information that detailed. Still, almost all of the climate<br />

models point to a much drier region by around 2050. “You<br />

could wait to the middle of the century and say, well, did<br />

this happen, or didn’t it happen” Seager says. “But that’s<br />

not a very sensible thing to do.”<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> Ink<br />

New Books by Faculty<br />

Order and Chivalry<br />

by Jesus D. Rodriguez-Velasco<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Pennsylvania Press<br />

Knighthood and chivalry are<br />

commonly associated with the<br />

aristocracy. However, Jesus D.<br />

Rodriguez-Velasco, professor of<br />

Latin American and Iberian studies<br />

at <strong>Columbia</strong>, is interested in<br />

how chivalric orders helped create<br />

the urban middle class in<br />

14th century Spain. Rodriguez-<br />

Velasco, who teaches medieval<br />

and early modern studies, relies<br />

on original texts to document the<br />

emergence of secular knighthood<br />

organizations in the Spanish kingdom of Castile. These organizations<br />

had rules that were different from those of military<br />

and religious orders for the nobility, and drew their membership<br />

from the ranks of city-dwelling commoners. Rodriguez-Velasco<br />

argues that these institutions helped define the privileges and<br />

political structures of modern Western society.<br />

The Gipper<br />

by Jack Cavanaugh<br />

Skyhorse Publishing<br />

Perhaps no sports legend is more<br />

enduring than that of Notre Dame<br />

football coach Knute Rockne and<br />

his star athlete George “The Gipper”<br />

Gipp, a former pool hustler and<br />

poker player still regarded by some<br />

as the best all-round player for the<br />

Fighting Irish. Jack Cavanaugh, a<br />

veteran sportswriter whose biography<br />

Tunney was nominated for a Pulitzer<br />

Prize, traces the lives of the two<br />

men as they intertwine on the Notre<br />

Dame football field in the years<br />

leading up to and just after World War I. Cavanaugh, a professor<br />

at the <strong>Columbia</strong> School of Journalism, details how Rockne and<br />

Gipp helped transform an unknown college football program into<br />

a national powerhouse and, in the process, cemented the phrase<br />

“Win one for the Gipper” in the popular imagination.<br />

The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and<br />

the Ordeals of Divine Election<br />

by Todd Gitlin and Liel Leibovitz<br />

Simon & Schuster<br />

Prolific author and Journalism Professor<br />

Todd Gitlin takes on the special<br />

relationship between the United<br />

States and Israel in his latest book,<br />

The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel,<br />

and the Ordeals of Divine Election. With<br />

co-author Liel Leibovitz, an editor of<br />

the online Jewish affairs magazine<br />

Tablet, Gitlin suggests that both nations<br />

share the conviction they were<br />

singled out by God to serve as a beacon<br />

to the world. They argue that this<br />

shared idea of divine destiny drove both the westward expansion of<br />

the United States and the establishment of a modern Jewish state<br />

in the biblical land of Israel. A belief in divine election doesn’t necessarily<br />

lead to arrogance and bad behavior, they contend; instead,<br />

the burden of “chosenness”—if shouldered properly—can offer a<br />

path to moral excellence.<br />

Importing Democracy<br />

By Raymond a. Smith<br />

Praeger<br />

The United States has always taken<br />

pride in being a model of democracy.<br />

However, presidential systems<br />

are more closely associated with<br />

dictatorship and single-party rule in<br />

other parts of the world like Latin<br />

America and Africa. Raymond A.<br />

Smith, adjunct professor of political<br />

science, explores whether American<br />

democracy might be strengthened<br />

by incorporating features of parliamentary<br />

systems. Each of the 21<br />

chapters highlights a feature of a<br />

foreign nation’s political system that is absent in the U.S. system.<br />

Chapters also draw on brief case studies from countries such as<br />

Australia, Brazil and South Africa.

6 january <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong><br />

New Mobile “App” Provides Earth Science Data<br />

new mobile application<br />

A created at Lamont-Doherty<br />

Earth Observatory provides users<br />

with simplified access to<br />

vast libraries of images and<br />

information that until now<br />

were tapped mainly by earth<br />

and environmental scientists.<br />

The EarthObserver<br />

App, for the iPhone, iPad or iPod<br />

<strong>University</strong> Launches Updated Website<br />

After months of public testing and<br />

user feedback, the revised and redesigned<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong>.edu home page was<br />

launched on Jan. 13. Designed by the<br />

Office of Communications and Public<br />

Affairs, in partnership with <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> Information Technology, it<br />

Touch, displays natural features<br />

and forces on land, undersea<br />

and in the air. The application<br />

draws on dozens of<br />

frequently updated databases<br />

from institutions throughout<br />

the world. For a slideshow of<br />

images available through the<br />

application, visit: news.columbia.edu/earthapp.<br />

contains a number of aesthetic, organizational<br />

and technological improvements,<br />

including simplified navigation; an enhanced<br />

search function that includes<br />

websites and contact information; and<br />

social media tools. To see more go to:<br />

news.columbia.edu/home/2266<br />

eileen barroso<br />

TheRecord<br />

Four Professors Elected Fellows of the American<br />

Association for the Advancement of Science<br />

By Record Staff<br />

Four <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>University</strong> professors have been<br />

elected fellows of the American Association for<br />

the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a prestigious<br />

scientific society<br />

established in 1848.<br />

The new fellows,<br />

selected from across a<br />

range of fields including<br />

political science,<br />

biology and epidemiology,<br />

are among 503 inductees<br />

from across the<br />

nation. Last year the<br />

AAAS recognized seven<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> professors as new fellows.<br />

Here are this year’s fellows:<br />

Wallace S. Broecker<br />

Wallace S. Broecker, Newberry Professor of<br />

Geology in the Department of Earth and Environmental<br />

Science, for pioneering contributions to the<br />

fields of climate science<br />

and oceanography.<br />

Broecker, who is<br />

also a researcher at<br />

the Lamont-Doherty<br />

Earth Observatory, was<br />

recognized for his understanding<br />

of glacial<br />

ages, circulation of the<br />

ocean and ocean biogeochemistry.<br />

Shih-Fu Chang<br />

Shih-Fu Chang, professor and department chair<br />

of Electrical Engineering at the School of Engineering<br />

and Applied Science (SEAS), for distinguished<br />

contributions to multimedia content analysis and<br />

Bruce Gilbert<br />

Dr. Cheryl Hutt<br />

search. Since the early 1990s, his research group<br />

has developed numerous popular visual search engines<br />

and intelligent multimedia communication<br />

systems.<br />

Peter Schlosser, Vinton<br />

Professor of Earth and Environmental<br />

Engineering<br />

at SEAS, for his important<br />

scientific accomplishments<br />

in ocean and hydrological<br />

sciences. Schlosser, who is<br />

also the director of the <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

Climate Center, was<br />

recognized for his contributions<br />

to sustainable development<br />

and his significant<br />

services to national and international scientific<br />

communities.<br />

Saul J. Silverstein, professor of microbiology<br />

and immunology at <strong>Columbia</strong>’s College of Physicians<br />

and Surgeons, for<br />

Saul J. Silverstein<br />

Peter Schlosser<br />

distinguished contributions<br />

to the field of biology<br />

and medical sciences.<br />

In particular, Silverstein<br />

was recognized for development<br />

of the process<br />

of cotransformation of<br />

mammalian cells, which<br />

allows foreign DNA to be<br />

inserted into a host cell to<br />

produce certain proteins.<br />

New fellows will be<br />

presented with an official certificate and a gold and<br />

blue (representing science and engineering, respectively)<br />

rosette pin on Feb. 19 during the <strong>2011</strong> AAAS<br />

annual meeting in Washington, D.C.<br />

Bruce Gilbert<br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> Staffer and Veteran Invited to President’s DADT Signing<br />

eileen barroso<br />

Domi in her office in Low Library.<br />

By Melanie Farmer<br />

Former U. S. Army Captain Tanya<br />

Domi could not believe her good<br />

fortune when she was invited to attend<br />

President Barack Obama’s signing of<br />

legislation to repeal the “don’t ask, don’t<br />

tell” policy banning gays and lesbians from<br />

serving openly in the military. For Domi,<br />

one of just 500 guests at the Dec. 22 ceremony<br />

in Washington, D.C., it struck very<br />

close to home.<br />

Domi, a senior public affairs officer in<br />

the Office of Communications and Public<br />

Affairs as well as an adjunct assistant professor<br />

of International and Public Affairs, had<br />

been investigated for her sexual orientation<br />

soon after enlisting in the Army.<br />

“It was surreal,” Domi says about the bill<br />

signing. “It’s amazing to go from being in<br />

the Army and being read my rights to standing<br />

in the Department of Interior listening<br />

to the president say, ‘We are not a don’t ask,<br />

don’t tell country.’”<br />

Domi, 56, enlisted in the Army in 1974,<br />

when she was 19. Six months after enlisting,<br />

she was accused of being a lesbian after going<br />

to a gay bar with other women from her company;<br />

all were privates stationed at Fort Devens,<br />

Mass. After an 18-month investigation,<br />

some women who had revealed they were gay<br />

were discharged from the Army.<br />

Domi retained counsel from the American<br />

Civil Liberties Union and refused to reveal her<br />

sexual orientation. She fought the charges,<br />

which were ultimately dropped, but the Army<br />

downgraded Domi’s top secret clearance and<br />

she was not permitted to participate in her<br />

graduation from military intelligence training.<br />

While she is now openly gay, she wasn’t at<br />

the time, and she was investigated twice more<br />

and, she says, sexually harassed by a colleague.<br />

Domi ultimately achieved the rank of captain<br />

before resigning her commission in 1990.<br />

“It was really dangerous for me to remain in<br />

the Army even though I loved the Army,” says<br />

Domi. When the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy<br />

became law in 1993, she worked to repeal<br />

it, testifying before Congress and speaking<br />

against it in 25 states.<br />

“The repeal legitimizes those who want<br />

to serve, who happen to be gay and lesbian,<br />

and want to be treated like everyone else in<br />

America. These values are quintessentially<br />

American,” Domi says.<br />

Born and raised in Indianapolis in a politically<br />

minded family, Domi was introduced to<br />

politics by her mother, who often volunteered<br />

as a judge at polling stations. At 13, she canvassed<br />

door-to-door for Robert F. Kennedy’s<br />

1968 presidential bid.<br />

Following her military service, working<br />

in politics seemed like a natural move. She<br />

worked in a series of political public relations<br />

and communications jobs, including for the<br />

House Armed Services Committee, the Clinton-Gore<br />

1996 re-election campaign and the<br />

Organization for Cooperation and Security<br />

in Europe in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where she<br />

helped implement the Dayton Peace Accords.<br />

In 2000, after a decade of working on issues<br />

such as sex trafficking, human rights and media<br />

freedom, often in the international arena,<br />

she moved to New York City to get a master’s<br />

degree in human rights at <strong>Columbia</strong>. Eventually<br />

she joined the public affairs office. After<br />

earning her degree in 2007, she also began<br />

teaching human rights as an adjunct professor<br />

of international affairs.<br />

Domi’s job includes promoting <strong>Columbia</strong>’s<br />

expertise in international affairs, politics and<br />

economics, including the School of International<br />

and Public Affairs and the <strong>University</strong>’s<br />

six regional institutes. She also serves as the<br />

primary press contact for all World Leaders<br />

Forum events, which have brought prominent<br />

political and global figures to campus.<br />

Domi says she never imagined a career in<br />

education but now she’s hooked. “I enjoy the<br />

intellectual stimulus of talking to all these brilliant<br />

people and listening to how they view<br />

the world,” she says. “I absolutely love it. I’m<br />

always learning something new.”<br />

Col. Harold Floody nominated Domi, then 35, for the Douglas MacArthur Leadership Award in 1989 as the top junior officer in the U.S.<br />

Army Support Command, Hawaii.

TheRecord <strong>January</strong> <strong>31</strong>, <strong>2011</strong> 7<br />

FACULTY Q&A<br />

Gavin<br />

Schmidt<br />

Q.<br />

By Record Staff<br />

We’re at a moment where the politics of climate change<br />

have been changing in ways that are worrisome to<br />

those who value the role of science in public policy. Why do<br />

you think that is<br />

If you take any political issue where there is some scientific<br />

component, one often finds that the depth of<br />

A.<br />

feeling in the public doesn’t correlate with how well understood<br />

that topic is. We saw the same thing with health care,<br />

genetically modified foods, vaccines. Most people who have an<br />

opinion about these things actually haven’t looked into it and<br />

don’t have a deep understanding of what’s going on. So when<br />

it comes to climate science, it’s not surprising that most people<br />

don’t actually know the difference between the ozone hole and<br />

climate change, and don’t have good sources for getting comprehensive<br />

information.<br />

How harmful is it to the research mission when<br />

Q. you have people in a public role attacking climate<br />

science<br />

A.<br />

POSITION:<br />

Adjunct Senior Research Scientist at the Center for<br />

Climate Systems Research at the Earth Institute<br />

Climatologist at NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies<br />

JOINED FACULTY:<br />

1996<br />

HISTORY:<br />

Contributing Editor, RealClimate.org<br />

Co-Chair, the CLIVAR/PAGES (Past Global Changes)<br />

Intersection Panel<br />

Associate Research Scientist/Research Scientist<br />

with Goddard Institute for Space Studies, <strong>Columbia</strong>’s<br />

Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the<br />

Center for Climate Systems Research, 1998-2004<br />

Postdoctoral Fellow, National Oceanic and Atmospheric<br />

Administration, 1996-1998<br />

It’s dangerous when politicians start to use scientific<br />

themes to further their political goals. Real<br />

science takes the information that is out there and tries to<br />

come up with the best explanation for what’s going on. The<br />

politicized science that people like Cuccinelli in Virginia<br />

are engaging in is completely different; they’ve already<br />

made up their mind and they just look for things that support<br />

it. That kind of picking and choosing what science<br />

you want to believe, depending on what political goal you<br />

want to achieve, is the antithesis of what science really is. It<br />

sends a chilling effect across the whole of the academy. The<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Virginia is very aware of the ramifications of<br />

this and is fighting this all the way to the Supreme Court in<br />

Virginia, and I wish them all the luck.<br />

Does the current polarized debate, much of it “antielitist”<br />

in tone, make it harder for scientists to win<br />

Q.<br />

public arguments outside the academy<br />

It takes a long time to become a scientist, and one of<br />

A. the reasons is because it’s hard. It’s hard to set aside<br />

prejudice and wishful thinking in order to see the world as<br />

it really is and to examine that world more critically. Science<br />

is always about nuance, it’s always about trying to step forward<br />

in a provisional way, one step at a time. It’s the collective<br />

information that science has produced that allows us to<br />

improve technology, to understand environmental threats,<br />

to understand the universe. The debates within science are<br />

always about small issues revolving around stuff that’s really<br />

cutting-edge. So when there’s a new paper in Nature or Science<br />

that is deemed to be of public interest, the real issue is<br />

not the subject—it’s a subtle point that has been worked out<br />

in the literature for years and years, and this may not even be<br />

a final accounting. Can that kind of approach survive when<br />

thrown into a political mosh pit Of course not. You’re not<br />

going to educate the public in the middle of a highly partisan<br />

political dog fight. We saw that with health care. The<br />

amount of misinformation and deliberate disinformation<br />

about health care reform was stunning to behold, and people<br />

were getting very, very angry about things that they didn’t<br />

understand. Climate change is like that and worse, because<br />

it’s less immediate.<br />

Q.<br />

A.<br />

Do you see the current challenges to climate science as<br />

a temporary conflict or something more long lasting<br />

The day-to-day attacks on scientific integrity, the accusations<br />

of misconduct and malfeasance, these must be<br />

dealt with. People need access to real information. There needs<br />

to be pushback when people are abusing their authority, as in<br />

the Virginia case. Just because there’s a growing awareness of<br />

the problem doesn’t mean that you can expect everything to<br />

work out nicely in the end. It will work out, I hope, because lots<br />

of work has been done to combat misinformation and put good<br />

information out there and help educate the public. But I don’t<br />

think there’s any guarantee that society will do the right thing<br />

in the long term unless in the short term we keep pointing out<br />

exactly what can be done and how that might help.<br />

Q.<br />

Give us some examples of things that scientists believe<br />

might work to solve the problem of climate change that<br />

are both good policy and good politics.<br />

A lot of the problem we have in developing climate<br />

A. policy is that it’s perceived to be different from other<br />

kinds of policy. The key to moving forward is to actually focus<br />

on things that can be done and how they might be done. Science<br />

says, okay, let’s talk about carbon dioxide—what effect is<br />

carbon dioxide having on the atmosphere But that isn’t necessarily<br />

the science that’s very useful for policymakers. One of<br />

the things our group has been working on in the last couple of<br />

years is trying to assess the net impact of a policy—not just for<br />

climate but also for air pollution, public health, water resources.<br />

We’re not talking about pie-in-the-sky targets; we’re talking<br />

about policy options that are on the table now, like increasing<br />

the CAFE standards for mileage [federal regulations to improve<br />

fuel efficiency]. They decrease carbon dioxide, but they also<br />

decrease nitrous oxides and black carbon. And what’s the net<br />

effect on the climate going to be once you take into account<br />

all those other things What you find is that there are a lot of<br />

policy options that are positive across a number of different<br />

criteria that policymakers care about. Policymakers don’t only<br />

care about the climate; they care about the health of the population,<br />

congestion, clean water and clean air. And so often times<br />

I think that the climate sciences have been perceived to be saying,<br />

“CO2, CO2, CO2, CO2,” which is right, but lacks nuance.<br />

Does a long-term problem like climate change—where<br />

Q. both the risks and the benefits may appear distant in<br />

time—present a special risk to a society that tends to address<br />

issues in response to an immediate crisis<br />

A.<br />

Historically we’ve dealt with environmental issues on<br />

a piecemeal basis. We’ve dealt with acid rain, dirty rivers,<br />

oil spills, but we haven’t really thought about it in a holistic<br />

way. It’s only been in the last five years that the big modeling<br />

groups have started to put these things together coherently so<br />

that you can ask good questions like, “If I change this, what impact<br />

is it going to have on climate, air pollution, public health,<br />

ecosystems and water” Since the science has moved forward,<br />

we can ask more interesting questions. And it turns out that<br />

those questions are the questions that policymakers have probably<br />