STATE OF VIOLENCE - FCAT

STATE OF VIOLENCE - FCAT

STATE OF VIOLENCE - FCAT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

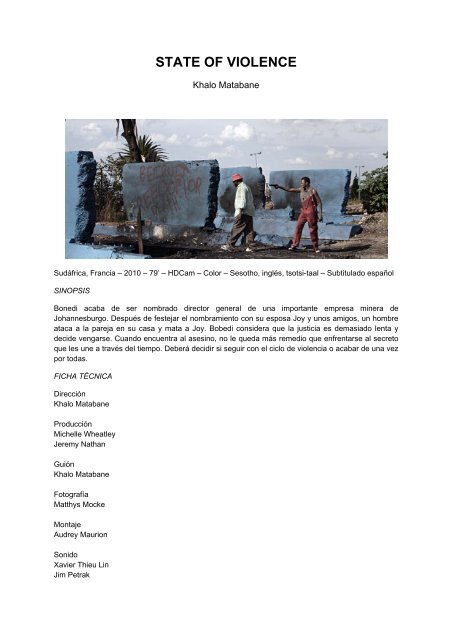

<strong>STATE</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>VIOLENCE</strong><br />

Khalo Matabane<br />

Sudáfrica, Francia – 2010 – 79’ – HDCam – Color – Sesotho, inglés, tsotsi-taal – Subtitulado español<br />

SINOPSIS<br />

Bonedi acaba de ser nombrado director general de una importante empresa minera de<br />

Johannesburgo. Después de festejar el nombramiento con su esposa Joy y unos amigos, un hombre<br />

ataca a la pareja en su casa y mata a Joy. Bobedi considera que la justicia es demasiado lenta y<br />

decide vengarse. Cuando encuentra al asesino, no le queda más remedio que enfrentarse al secreto<br />

que les une a través del tiempo. Deberá decidir si seguir con el ciclo de violencia o acabar de una vez<br />

por todas.<br />

FICHA TÉCNICA<br />

Dirección<br />

Khalo Matabane<br />

Producción<br />

Michelle Wheatley<br />

Jeremy Nathan<br />

Guión<br />

Khalo Matabane<br />

Fotografía<br />

Matthys Mocke<br />

Montaje<br />

Audrey Maurion<br />

Sonido<br />

Xavier Thieu Lin<br />

Jim Petrak

Dietary Keck<br />

Intérpretes<br />

Fana Mokoena<br />

Presley Chweneyagae<br />

Neo Ntlatleng<br />

Lindi Matshikiza<br />

Vusi Kunene<br />

Premios / Prix / Awards<br />

Milano 2011<br />

Khalo Matabane<br />

Biografía<br />

Khalo Matabane nació en Sudafrica. Tiene en su haber varios documentales para televisión, entre los<br />

que destacaremos Young Lions (2000) y Love in the Time of Sickness (2002), así como<br />

documentales para cine como Beautiful Country (2004) y Conversations on Sunday Afternoon (2006),<br />

ambos estrenados en la gran pantalla. Asimismo, dirigió la serie de cuatro capítulos When We Were<br />

Black (2008).<br />

Filmografía<br />

1996 Two Decades Still (doc) – 1998 The Waiters (doc) – 2000 Young Lions (doc) – 2002 Love in the<br />

Time of Sickness (doc) – 2004 Story of a Beautiful Country (doc) – 2006 Conversations on Sunday<br />

Afternoon (doc) – 2008 When We Were Black (tv) – 2010 State of Violence (lm)

Proverbio de las dos tumbas<br />

POR JUAN G. ANDRÉS - Domingo, 10 de Abril de 2011 - Actualizado a las 05:43h<br />

'State of violence'<br />

Sudáfrica-Francia, 2010. Guión y dirección. Khalo<br />

Matabane. Fotografía. Matthys Mocke.Música. Max Richter, Stéphane<br />

Moucha. Montaje. Audrey Maurion. Intérpretes. Fana Mokoena, Presley<br />

Chweneyagae, Neo Ntlatleng, Lindi Matshikiza, Vusi Kunene. Duración. 79<br />

minutos.<br />

LA cuestión sudafricana vuelve a servir de argumento al Festival de Cine y<br />

Derechos Humanos un año después de la proyección de la<br />

notable Endgame (2009) del cineasta Pete Travis. Si aquella cinta abordaba en<br />

clave de thriller político las conversaciones que pusieron fin al apartheid, State<br />

of Violence (2010) transcurre en la época actual pero describe hechos ficticios<br />

derivados de aquel tiempo convulso.<br />

El director Khalo Matabane se decanta por un tono áspero y sosegado en un<br />

filme sin actores-estrella y con una puesta en escena espartana, rayana casi en<br />

lo televisivo. Cuenta, sin embargo, con un acertado y recio guión,<br />

protagonizado por un hombre que recibe la trágica e inesperada visita de un<br />

pasado no muy lejano. Porque no hace tanto tiempo -poco más de 20 añosque<br />

los partidarios más radicales del Congreso Nacional Africano de Mandela<br />

mataban a los negros que colaboraban con el apartheid mediante el<br />

denominado necklacing, un linchamiento que consistía en colocar un neumático<br />

en el cuello del traidor, rociarlo de gasolina y prenderle fuego.<br />

Con una efectiva economía de medios y altas dosis de credibilidad, Matabane<br />

plantea cuestiones tan interesantes como la imposibilidad de pedir perdón -que<br />

en ocasiones puede resultar más difícil incluso que perdonar-, e interroga al<br />

espectador y a sus personajes sobre el (sin)sentido de la violencia, la venganza<br />

y el conflicto fratricida. Lo resume ejemplarmente el proverbio que alguien cita<br />

en el ecuador de la película. "Cuando quieras vengarte, cava dos tumbas: una<br />

es para tu enemigo; la otra para ti".

CULTURA<br />

«La violencia es una bola que<br />

no para de rodar»<br />

El sudafricano Khalo Matanabe indaga en los rencores y traiciones<br />

dentro de la familia en 'State of Violence'<br />

10.04.11 - 04:43 -<br />

RICARDO ALDARONDO | SAN SEBASTIÁN.<br />

«Muchas veces se piensa que en Sudáfrica el problema siempre está entre los<br />

blancos y los negros. Pero el apartheid también ha creado problemas entre los<br />

propios negros. No hemos tenido oportunidad de hablar entre nosotros, de dialogar<br />

entre las familias, entre los vecinos», afirma el director sudafricano Khalo<br />

Matabane, que esta tarde a las 19.00 horas presenta su película 'State of Violence'<br />

en el Victoria Eugenia, en una nueva jornada del Festival de Cine y Derechos<br />

Humanos de San Sebastián.<br />

«Quería hablar de la violencia, que es una bola que no para de rodar, y que es<br />

difícil detener», explicaba ayer Matanabe en San Sebastián. «Pero también quería<br />

ver qué significa pertenecer a una familia, ser fiel a tus camaradas, o seguir<br />

considerando a las personas que tienes cerca más importantes que las ideas<br />

políticas». 'State of Violence' no habla exactamente de política, sino de cómo las<br />

circunstancias del pasado siguen teniendo consecuencias en la familia y el entorno<br />

del protagonista, y cómo el perdón es necesario para detener la violencia. «Pero a<br />

veces se sufre tanto que ya no se es capaz de perdonar. Por eso es tan admirable<br />

lo que hizo Mandela después de 27 años en la cárcel».<br />

Matanabe, que tiene en su haber otros documentales, como 'Conversations On a<br />

Sunday Afternoon' y también escribe en la prensa sobre política, explica que la<br />

situación de la población negra en Sudáfrica es compleja: «No sólo intervienen<br />

cuestiones sociales, también económicas. Algunos negros se ha enriquecido<br />

mucho con su participación en grandes empresas, pero eso no ha redundado en la<br />

mejora de la situación de la población negra en general».<br />

Otra película destaca en la jornada de hoy, el nuevo filme de la directora Claire<br />

Denis, 'White Material' que habla de la situación de una familia que trata de<br />

mantener su plantación de café en un país de África, en medio de las revueltas y,<br />

de nuevo, de la violencia.

Khalo Matabane: State of Violence<br />

The South African director, who went from writing documentaries early in his career to<br />

dealing with fiction, makes his Berlinale debut with a tense, compelling action film with<br />

documentary approach to daily life in his home country.<br />

Sum up your film in one sentence.<br />

Film about memory and denial.<br />

How did you come up with the initial idea<br />

Because violence is such a typical theme in South Africa and the world, I wanted to<br />

understand it deeper.<br />

If you could show your film in a double feature, which would be the other<br />

one<br />

I would screen it with [Michael] Haneke’s film Caché, because I love it and the themes<br />

of denial are similar.<br />

Why do you make films<br />

I love telling stories.<br />

If you didn’t make films, what would you do<br />

Be a Buddhist monk.<br />

What would you like to be remembered for<br />

Living my life to the fullest and being kind, generous and fair.<br />

Take two films on a desert island…<br />

Raging Bull by Martin Scorsese and Akira Kurosawa’s Ran.<br />

A film or director that changed your life Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and<br />

Costa-Gavras’s Z.<br />

Describe one of your favourite scenes in a film of your choice.<br />

The scene in The Godfather where the Al Pacino character confronts his brother who<br />

has just betrayed him and ends up killing him. Heartbreaking.<br />

February 3, 2011

Home News News Archive 2010 August 2010 A city divided, a State of Violence<br />

A city divided, a State of Violence<br />

26 August 2010<br />

Khalo Matabane's first dramatic feature "State of Violence", the opener at last month's Durban<br />

International Film Festival, is a fascinating insight into a Johannesburg divided by wealthand<br />

class, exploring issues of memory, denial, forgiveness and revenge. Andrew Worsdale looks at<br />

the film's treatment of the city's contradictions and its place in the development of Matabane's<br />

unique cinematic voice.<br />

Khalo Matabane is an auteur. His films reflect a singular, personal vision and, although driven<br />

by sociopolitical themes from the legacy of the struggles against apartheid to issues of<br />

xenophobia and the individual's place in the new South Africa, his movies are never didactic<br />

agit-prop exercises. Matabane's individualist style is always more interested in questioning<br />

different realities than providing clear-cut answers.<br />

His feature-length documentary "Story of a Beautiful Country" redefined the notion of both road<br />

movie and documentary as he told the stories of ordinary people from the back of a minibus<br />

taxi.<br />

His 2006 film "Conversations on a Sunday Afternoon" was a perceptive and compelling feature<br />

length docu-drama set in Joburg's inner city that explored the lives of refugees and examined<br />

topics such as migration, displacement and Johannesburg's new-found role as a haven for<br />

refugees from both Africa and the rest of the world. The film was named best South African film<br />

at that year's Durban Fest and Won the Ecumenical Prize at the Berlin Film Festival.<br />

His four-part television series "When We Were Black" was a complex, intelligent and warm look<br />

at the innocence and naivety of people on the brink of adulthood in the midst of the seminal<br />

1976 Soweto uprising.<br />

I've hung out with Khalo, even did a spot of acting for a bread and butter TV show he directed,<br />

and his favourite comment when enthused about virtually anything is, "That's really,<br />

really interesting." Forever enquiring, looking between the lines in events or conversations,<br />

Matabane is a determined cineaste and a lover of both movies and polemic, making him,<br />

possibly, South Africa's foremost intellectual filmmaker.<br />

With his first feature-length fictional narrative, the analytical director chose to focus on themes<br />

of betrayal, revenge and the legacies of the past. As "State of Violence" producer Jeremy<br />

Nathan says of their development process: "Constantly Khalo watches films, from anywhere in<br />

the world, obsessively, texting ideas to his large group of socially networked friends, testing his<br />

political and storytelling thoughts to an initial virtual audience."<br />

Khalo approached Nathan's Dv8 Films over five years ago with a rough outline and concept for<br />

a feature film about a comrade from the struggle for liberation who had risen from debilitating<br />

poverty to a position of great wealth in the new South Africa. "Key to the plot was the fact that<br />

our lead character, as an angry young kid in the 1980s fighting the apartheid regime, its police<br />

and soldiers, had killed a sellout in his own community - a policeman," says the producer.<br />

The scripting, casting and production process became part writing, with much debate and<br />

discussion, and part workshop with French screenwriter and script editor Jacques Akchoti, more<br />

input from various partners and funders and deep discussions with the cast and crew, led to an<br />

inclusive creative process that allowed for input from everyone on the team.

The film tells the story of Bobedi (Fana Mokoena), who, when his wife is killed, is forced to go in<br />

search of the killer. His search takes him out of his comfort zone in wealthy Sandton and back<br />

into Alexandra township, a place of buried memories. When he finds out that the killer is his own<br />

cousin, his dead uncle's son, he is forced to deal with the family he left behind. Starring opposite<br />

Mokoena is Presley Chweneyagae, famous globally for his performance in "Tsotsi", who plays<br />

the role of Boy-Boy.<br />

They are joined by veteran actors Mary Twala, Vusi Kunene, Lindi Matshikiza, Tinah<br />

Mnumzana, Harriet Manamela and Neo Ntlatleng. "At the core of Khalo's investigation was his<br />

deep desire to understand why violence is so embedded in our national psyche, how poverty,<br />

perpetual conflict and the long history of colonisation and apartheid have created a nation of<br />

extremely violent people, who continue to perpetrate acts of violence so easily," says Nathan.<br />

With his documentary background and constantly prying mind Matabane went about<br />

conceptualising the narrative for the film through an intense development process based on<br />

character which carried through into production.<br />

"The way the film was shot was interesting because it was a collaborative effort and we all had<br />

freedom on set and the cast and heads of departments came with ideas," he says.<br />

"It was during this process that the story became even more intimate and I realised that the<br />

strength of the story was in the family dynamics. The film deals with themes of memory, denial,<br />

ideology versus family, the wealth of Sandton versus the poverty of Alexandra township in a<br />

subtle way. Is it better to remember or to forget And when should we forget and when should<br />

we remember"<br />

In his director's treatment for the film, prepared together with the script to attract finance,<br />

Matabane wrote: "The violent act that the main character, Bobedi, experiences, forces him to<br />

escape his comfort zone of his suburban life. Like me, he lives in a predominantly old Jewish<br />

neighborhood.<br />

"He embarks on a journey into the underbelly of Johannesburg, a harsh and brutal landscape<br />

full of contradictions. The few exceptionally wealthy people who lock themselves in gated<br />

communities with security guards and electric fences provide a stark contrast to the rest of the<br />

population who are the wretched of the earth.<br />

The dream of forging national reconciliation and a just and equitable society has failed and<br />

Johannesburg is a place of broken dreams where dog eats dog. It is a city of greed where<br />

money buys the characters almost anything except their souls."<br />

Despite these harsh words Khalo says: "The film does not judge or offer moral solutions, but<br />

rather it intends to provoke and leave an audience to make up their own minds about violence,<br />

especially in a world where the marginalised increasingly feel the need to resort to violence as<br />

an act of desperation to make themselves heard."<br />

After its Durban world premiere, online critic Roger Young described the film as "not a standard<br />

vigilante film, it's more about a state of mind a stark, stripped down and affecting film about the<br />

numbness of revenge".<br />

Nathan says that what differentiates "State of Violence" from other South African films is that "it<br />

does not ever deal with simplistic racial violence. Uniquely, it focuses on the brutal affects of<br />

poverty and apartheid on the black family unit, and how this family unit has been devastated<br />

over time, its fragility sustained largely by women.<br />

"By linking our behaviour in the present, to the consequences of our actions in the past, the film<br />

raises questions more than giving answers, about whether true forgiveness in a post colonial,<br />

post apartheid society, is actually really achievable."<br />

The powerful revenge thriller was shot in 30 days late last year, mostly in the poverty-stricken<br />

township of Alexandra, five minutes from Sandton, the wealthy heart of Johannesburg. The<br />

contrast between these two worlds - one unbelievably rich and modern, the other almost<br />

medieval in its poverty - is a metaphor for a man caught between his past and his present, who<br />

grew up in the grinding poverty of Alex, and who now lives the high life in Sandton.<br />

These contrasts formed a fascinating visual conflict for the film. "The colours of Sandton before<br />

Bobedi's wife dies are warm in contrast to being cold after she has been killed," says the<br />

director. "Alexandra township colours are bleached and white, it's hot, everything is grey and

own, a decaying brown of everything that is old. The colours accentuate the wealth in<br />

Sandton and the poverty in Alexandra township."<br />

The contrast was not only visual but aural as well. "The film does not use scored music but<br />

different sound designs," says Matabane. "We hear the sound that he hears and sometimes it's<br />

a sound that haunts him, like his wife sobbing before she dies or it's a distorted sound.<br />

"The sound of wealthy Sandton is different from the one in Alexandra township. The suburb is<br />

quiet except for the birds and dogs barking and alarms going off, while Alexandra is very loud -<br />

traffic, different musical styles, loud radios playing, taxis hooting."<br />

The film was a complex coproduction but the producers had to find partners sensitive to<br />

Matabane's process as a director. Collaborators included the National Film and Video<br />

Foundation (NFVF), SABC, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) Rebate, the Industrial<br />

Development Corporation (IDC) and the Gauteng Film Commission (GFC) in South Africa.<br />

Nathan is full of praise for the GFC, saying: "They were and still are a powerful partner on the<br />

project, from preproduction through to distribution."<br />

Foreign support came from the French CNC's Fonds Sud and Italy's Unidea together with Diana<br />

Elbaum and Sebastien Delloye's Liaison Cinematographique, the French coproducer, who also<br />

brought the sales company, Pyramide International, to the film.<br />

Despite the complexities and the agendas that come with a coproduction like this the everreflective<br />

Khalo sighs and says: "It was important that I did my first fiction film with producers<br />

who understand the importance of bringing a directorial voice to the screen, and I think it is<br />

visible in this film.<br />

"The themes that fascinate me - history, memory, religion and the process of filming, part<br />

conventional, part improvised. 'Violence' is a film in which I try to find my cinematic voice, one<br />

that is influenced by my growing up in a village with a strong oral traditional of story-telling, my<br />

experiences as a documentary filmmaker, my love for different genres of cinema, from different<br />

eras and continents and ideologies.<br />

It is in the end a cinema of a film traveller and lover, one who likes to provoke with cinema. It is<br />

what I call the cinema of the dreamers."<br />

This particular dream of Matabane's is about to infiltrate film festivals across the globe over the<br />

next few months, from Toronto to Pusan, Carthage and Dubai. It's scheduled for a local release<br />

in March next year.