PDF-document, 3,5 MB - Bok & Bibliotek

PDF-document, 3,5 MB - Bok & Bibliotek

PDF-document, 3,5 MB - Bok & Bibliotek

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

In FOcus<br />

German language literature<br />

Deutsch<br />

– about the small language and the big<br />

With smallness – and Swedish is a very small language indeed<br />

– you always run a risk of disappearing completely. The minor<br />

is pushed aside by the major. The little language dwindles into<br />

insignificance, loses its place in writing and ends its days in the<br />

form of phrases or interjections in farmyards or at the pub. That is<br />

what has happened, over less than a century, with all the Romanian-speaking<br />

villages near my own village in Istria. There, no one<br />

speaks Romanian any longer. Or, the last one to do so lacks an understanding<br />

ear nearby capable of comprehending what is being<br />

said (talking to oneself is no solution in the long run). Nor does it<br />

help to have the language in written form, if no one who can read<br />

is capable of understanding it.<br />

Those in the know will tell you that a small language like that<br />

disappears from our world every day.<br />

When you're big – and German is a very big language – you<br />

needn't fear extinction, or even suppression or invasion. The big<br />

language is safe and arrogant. Some of them already find loanwords<br />

to be a nuisance. But a big language can violate itself: the<br />

German language did so for more than a decade in the last century.<br />

A short time, considering the thousand years they had in mind, but<br />

long enough to be devastating.<br />

For the big language, a small one is rarely of any interest, other<br />

than as folklore or quaint curiousity. One's own is enough, sufficient<br />

in itself. It holds everything you need. Often, for the same<br />

reason, other major languages are treated with mild interest and<br />

their classic works are only taken into account once they have<br />

been translated into your own language. A – translated – Shakespeare<br />

might then be counted almost as a German writer.<br />

But a small language cannot afford the luxury of huddling in<br />

its own, confined world. The only way for a Swede, a Czech or a<br />

Hungarian to keep cultural hunger at bay is to learn at least to read<br />

in other languages besides one's native tongue. This necessity, born<br />

out of want and isolation, has many advantages. Thus, a Romanian<br />

or a Pole is seldom as parochial as a French or American, content<br />

with strolling through his own, seemingly boundless, linguistic<br />

garden.<br />

us to look at ourselves from the outside. In all our history it's likely<br />

that only Latin has had as important a role.<br />

All of this, however, ended in 1945. From then on English takes<br />

centre stage.<br />

Why should this be<br />

English is, of course, the language of the victors, representing<br />

a new and modern world, as full of promises as it then seemed<br />

innocent. But I don't think that this explanation quite covers it. In<br />

our country, the switch from one secondary language to another<br />

is so abrupt and complete as to resemble collective amnesia or<br />

censorship.<br />

I rather tend to believe that it has to do with shame; the shame of<br />

having done too little at a time when so much more than the German<br />

language was at stake. After 1945, no one in Sweden was very<br />

keen on remembering this time of humiliating adaptation and<br />

silence. Accordingly, not just the years in Germany's shadow have<br />

been suppressed, but also the German language that reminds us<br />

of them.<br />

In this radical abolition of such a vital piece of our cultural<br />

soil, we also lost things we needn't be ashamed of. These days few<br />

people know that the S. Fischer Publishing House, home to a multitude<br />

of the greatest German-speaking writers, found a safe haven<br />

through the Bonnier family in Sweden. Here Fischer published<br />

books that had already been thrown on the bonfires in Germany<br />

and whose writers had been driven into exile or blacklisted. Some<br />

of these books – Stefan Zweig, Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel – can<br />

be found on my shelves, finds from Stockholm's various secondhand<br />

bookshops, attics and cellars.<br />

In Germany, they are rarities.<br />

Thus a homeless big language could once find shelter with a<br />

small one. Not for long, not without problems; but still. Perhaps<br />

this can be regarded as a humble gesture of<br />

gratitude towards a language that meant so<br />

much for our Swedish culture before its sudden<br />

disappearance from it.<br />

For a long time, German was the first foreign language learned<br />

by Swedes. It was German who raised us from our ‘Kråkvinkel’, incidentally<br />

a German loan-word (meaning ‘backwoods’), enabling<br />

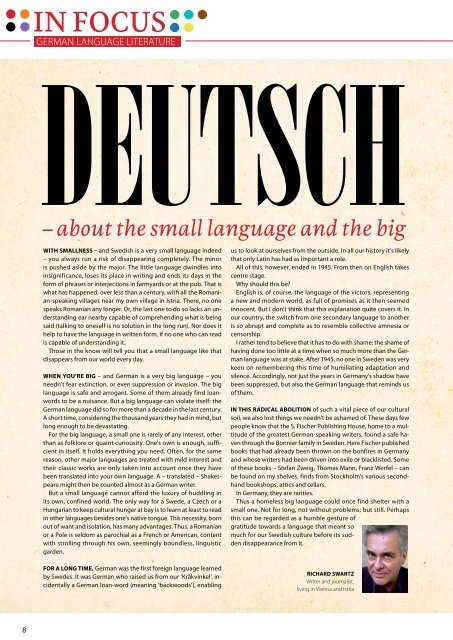

Richard Swartz<br />

Writer and journalist,<br />

living in Vienna and Istria<br />

8