Volume 33 Number 3 June 2006 - International Clarinet Association

Volume 33 Number 3 June 2006 - International Clarinet Association

Volume 33 Number 3 June 2006 - International Clarinet Association

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

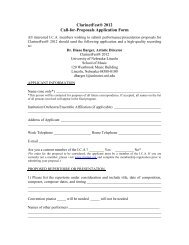

PART III: THOUGHTS<br />

ON ARTICULATION<br />

The author has surveyed early clarinet<br />

specialists from around the world while<br />

writing the D.M.A. dissertation “Early<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Performance as Described by<br />

Modern Specialists, with a Performance<br />

Edition of Mathieu Frédéric Blasius’s IIe<br />

Concerto de clarinette,” under the supervision<br />

of Dr. Kelly Burke at the University of<br />

North Carolina at Greensboro. Third in a<br />

series, this article will examine techniques<br />

and performance practice of articulation<br />

on the early clarinet. Following articles<br />

will discuss reeds, instrument selection<br />

(originals, modern replicas), and selected<br />

repertoire with reference to performance<br />

practice of the early 19th century.<br />

Studying the early clarinet has enhanced<br />

and clarified my understanding<br />

of the essays by C.P.E.<br />

Bach, Lefèvre, Leopold Mozart, Quantz<br />

and Türk. Playing through the musical<br />

examples with a boxwood instrument<br />

changes the perception of notation, articulation,<br />

accentuation, phrasing, and suggests<br />

many parallels to rhetoric. The descriptions<br />

and illustrations are materialized<br />

by the natural response of the instrument.<br />

This experience has consequently<br />

helped me appreciate the lesser-known<br />

works of the clarinet repertoire.<br />

With respect to articulation, the discourse<br />

is analogous between string, keyboard<br />

and woodwind treatises. Period<br />

bows and keyboards were not designed to<br />

play sostenuto, and therefore a natural<br />

decay of sound occurred after each articulation:<br />

“Leopold Mozart taught that ‘if in a<br />

musical composition two, three, four, and<br />

even more notes be bound together by a<br />

half-circle [slur] … the first of such united<br />

notes must be somewhat more strongly<br />

stressed, be the remainder slurred on to it<br />

quite smoothly and more and more quietly.”<br />

1 The narrow bore and soft reed of the<br />

early clarinet respond in a similar manner.<br />

When a performer attempts to eliminate<br />

the naturally occurring decay — blowing<br />

through it — the instrument sounds choked<br />

and unresponsive.<br />

Woodwind articulation is analogous to<br />

bowing for string instruments, fingerings<br />

for keyboard players, and text for vocalists.<br />

Lefèvre makes this parallel in his Méthode:<br />

Page 38<br />

Early <strong>Clarinet</strong> Pedagogy<br />

for Modern Performers<br />

by Luc Jackman<br />

L’articulation des instruments à<br />

cordes se fait par le moyen, ou de<br />

l’archet, comme le violon, ou des<br />

doigts, comme la harpe, [et] la guittare.<br />

Celle des instruments à vent se<br />

fait par la langue: sans la langue il<br />

est impossible de bien jouer de la<br />

clarinette, elle est a cet instrument<br />

ce que l’archet est au violon; l’action<br />

de la langue qui determine l’articulation<br />

s’appelle coup de langue,<br />

pour donner les coups de langue il<br />

faut boucher l’anche avec la langue<br />

puis la retirer pour introduire l’air<br />

dans l’instrument en prononçant la<br />

syllabe TÛ. 2<br />

The beginning of a tone and its relationship<br />

to the preceding and following<br />

ones is intimately related to the quality of<br />

a sound. Proper articulation is perhaps the<br />

most important parameter for successfully<br />

playing music from the 18th and early<br />

19th centuries, as it is used to stress dissonance,<br />

clarify harmony, emphasize melodic<br />

line, define rhythmical structure, and<br />

separate phrases or sections of a phrase.<br />

Performers are responsible for crafting articulations<br />

that will ultimately “sing” the<br />

musical phrase.<br />

The main differences between articulating<br />

on early and modern clarinet arise<br />

from the wider angle at which the former<br />

is played, which places the reed lower in<br />

the mouth, thus reducing the distance traveled<br />

by the tongue from a neutral position;<br />

the reed position, if one chooses to veer<br />

from the comfortable untersichblasen<br />

(mandibular embouchure); the variety of<br />

resistances between notes and fingerings,<br />

and the greater flexibility of the reed, used<br />

to counterbalance the high resistance of<br />

the instrument. The early clarinet offers a<br />

great variety of articulations: Backofen<br />

describes three ways of articulating on the<br />

early clarinet, using the tongue, lips, or<br />

throat. Another technique described in<br />

early clarinet methods is the air attack, or<br />

chest articulation: It is produced by lightly<br />

pushing the abdominal muscles out, as<br />

when pronouncing a gentle yet firm “ha.”<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

The later is especially useful in soft entrances,<br />

or in combination with other<br />

types of articulation.<br />

With the reed-under technique, tonguing<br />

is done largely the same as with modern<br />

reed instruments — produced through<br />

different syllables. Consonants influence<br />

placement, motion, and release of the<br />

tongue. Vowels place the middle and back<br />

portions of the tongue at different heights:<br />

An “ah” sound brings about a lower tongue<br />

position than an “ee” or French “u” sound.<br />

The early methods describe two basic consonants<br />

for tonguing, which are a “t” sound<br />

and a softer “d” sound. It is also possible to<br />

articulate with the tongue using “l,” “n”<br />

and “th.” With the reed-above, these consonants<br />

may be performed by the interaction<br />

of the tongue with the hard palate.<br />

Lip articulations are performed by tightening<br />

the grip around the reed and mouthpiece.<br />

The consonants visualized for this<br />

technique are “p” and “w.” The jaw may<br />

assist the lip muscles in this technique, but<br />

if too much pressure is needed to close off<br />

the air input, the reed is probably too hard.<br />

Throat articulation is the opening and closing<br />

of the soft palate to let the air through.<br />

This is performed with the “gu” and “k”<br />

sounds, or by pretending to cough gently<br />

into the clarinet.<br />

Experimenting with the above-mentioned<br />

techniques provides the clarinetist<br />

with a wide palette of articulation for musical<br />

expression: They can reach a level<br />

of subtlety that is not possible on the modern<br />

instrument. Where to start was the<br />

main issue for me… The instrument itself<br />

led the way at first, however playing<br />

within a chamber music setting proved to<br />

be the most educational experience in<br />

developing my palette of articulations.<br />

The aforementioned techniques will be<br />

illustrated through the clarinet literature<br />

in subsequent articles.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Bach, C.P.E. Versuch über die wahre Art<br />

des Clavier zu spielen. Translated by<br />

William J. Mitchell. New York: W.W.<br />

Norton & Co., 1949.