1945 Windbreaks: Natural Erosion Control - webapps8

1945 Windbreaks: Natural Erosion Control - webapps8

1945 Windbreaks: Natural Erosion Control - webapps8

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

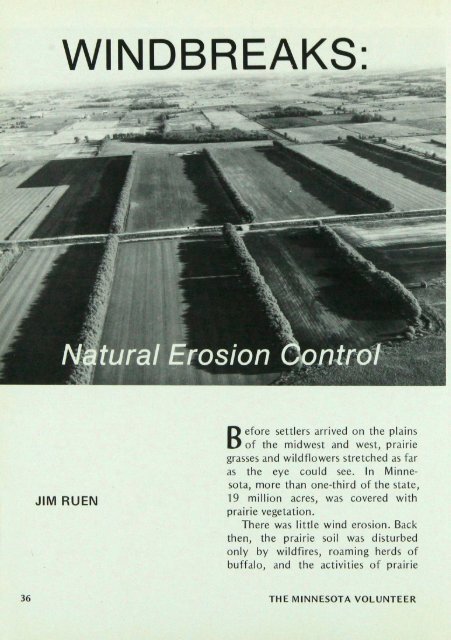

WINDBREAKS<br />

Before settlers arrived on the plains<br />

of the midwest and west, prairie<br />

grasses and wildflowers stretched as far<br />

as the eye could see. In Minnesota,<br />

more than one-third of the state,<br />

JIM RUEN million acres, was covered with<br />

prairie vegetation.<br />

There was little wind erosion. Back<br />

then, the prairie soil was disturbed<br />

only by wildfires, roaming herds of<br />

buffalo,<br />

and the activities of prairie<br />

36 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

dogs and other wildlife. But then came<br />

the western movement and the moldboard<br />

plow. Before long, vast expanses<br />

of prairie were replaced by corn and<br />

wheat. Cattle and sheep often overgrazed<br />

vegetation that was not plowed<br />

under.<br />

The importance of trees on the<br />

open prairie was recognized as early as<br />

1873 with passage of the Timber<br />

Culture Act. This bill offered homesteaders<br />

160 acres if they would plant<br />

trees on 40 acres. The Act was repealed<br />

less than two decades later, but<br />

not before millions of trees had been<br />

planted.<br />

Meanwhile, taming of the wild<br />

prairie continued. More land was converted<br />

to crops so that, by the end of<br />

the century, the frontier was virtually<br />

closed.<br />

Dirty Thirties. It didn't take long<br />

before Americans began to pay the<br />

price for destroying the prairie grasses<br />

and flowers which had held the dry,<br />

sandy soil in place. And the price was<br />

high—the infamous dust bowl of the<br />

1930s. Drought came to the prairies.<br />

Older farmers still tell of dust clouds<br />

hundreds of feet high, burying<br />

machinery and fence lines in drifts of<br />

soil. With farm prices at rock bottom<br />

because of the depression, the drought<br />

forced many farmers off the land.<br />

The federal government declared<br />

war on the devastating erosion by<br />

establishing the Prairie States Forestry<br />

Project in 1935. The project provided<br />

money for the Work Progress Administration<br />

(WPA) and the Civilian Conservation<br />

Corps (CCC) to plant trees for<br />

erosion control. From 1935 to 1942,<br />

more than 200 million trees and<br />

shrubs were planted from Texas to<br />

Minnesota and from the Rocky Mountains<br />

to the eastern border of<br />

Nebraska. More than 238,000 acres<br />

were planted to windbreaks.<br />

These shelterbelts proved invaluable.<br />

They broke the force of the<br />

ever-present prairie wind, protecting<br />

soil particles along with newly-planted<br />

seed and young plants. The windbreaks<br />

reduced evaporation from the<br />

soil and trapped snow during winter,<br />

saving moisture for the coming growing<br />

season. They beautified the landscape<br />

and improved living conditions<br />

for humans, livestock, and wildlife.<br />

But once again man is changing the<br />

pattern of the prairie. With renewed<br />

emphasis on expanded farm production,<br />

higher land values and resulting<br />

higher taxes, farmers are striving to get<br />

the most from their acres. The recent<br />

drought, for example, catalyzed a<br />

boom in farmland irrigation on sandy<br />

soils.<br />

Today, many people fear that, as<br />

irrigation grows, the windbreak will go<br />

the way of the big bluestem and the<br />

prairie conefiower. Many shelterbelts<br />

are in the way of the sweep of center<br />

pivot irrigation systems, and thus are<br />

being wholly or partially removed.<br />

Windbreak removal is not a serious<br />

problem in Minnesota, but it is occurring<br />

in the southern plains states<br />

where snow retention is not a factor<br />

)ANUA RY —FEBRUARY 1978 37

System developed in Nebraska (left) shows section of center pivots<br />

and windbreaks. Trees are primarily red cedars six feet apart in two to<br />

four rows. Right: Low-growing shrubs across diameter of quartersection<br />

center pivot circle is being tried in North Dakota. Fifty-foot<br />

Cottonwood, or northwest poplars, border outer edge of North<br />

Dakota system. (Artwork courtesy of Irrigation Age magazine.)<br />

and in areas where center pivot irrigation<br />

is being installed.<br />

To aid farmers in soil erosion control<br />

under center pivot irrigation systems,<br />

the SCS advises use of annual<br />

row crops such as corn or the planting<br />

of shrubs at intervals throughout the<br />

field.<br />

Few farmers are using shrubs because<br />

of the expense and labor needed<br />

to keep the plantings trimmed to a<br />

height below the center pivot boom. If<br />

a mechanical hedge row trimmer could<br />

be developed, interest in shrubs would<br />

increase greatly.<br />

Irrigation is a relatively recent development<br />

in Minnesota agriculture,<br />

one which is growing rapidly. As of<br />

last June, 387,000 acres were sprinkler<br />

irrigated. It is estimated that at least<br />

two-thirds of this acreage is under<br />

center pivot systems.<br />

"Five years ago, shelterbelts were<br />

being torn out to accommodate center<br />

pivots, but with no provision to replace<br />

the trees," said Fred Bergsrud,<br />

Irrigation Specialist at the University<br />

of Minnesota. "Today farmers have<br />

become more aware of the potential<br />

problems. Ottertail County was the<br />

first to notice a problem with wind<br />

erosion. There and in similar areas in<br />

Minnesota the SCS and the University<br />

are working with farmers to find a<br />

solution."<br />

New Ordinance. Sherburne and<br />

Benton counties, two rapidly ex-<br />

38 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER

panding irrigation areas, have suffered<br />

soil losses because of windbreak removal.<br />

Benton County commissioners<br />

have passed an ordinance controlling<br />

removal of windbreaks, one of the few<br />

such laws in the nation. It requires<br />

farmers to develop alternative plans<br />

for soil conservation before they can<br />

remove a field windbreak. Kevin Adelman,<br />

SCS technician for the two<br />

counties, said the ordinance has cut<br />

windbreak removal in half.<br />

About 30 miles of windbreaks have<br />

been removed in Benton and Sherburne<br />

counties, mainly because of new<br />

irrigation projects. But only two miles<br />

have been replaced. William Held of<br />

Rice has started to replace some of the<br />

six miles of shelterbelt he removed,<br />

planting trees on the perimeter of his<br />

fields. (<strong>Windbreaks</strong> on the outside of a<br />

field do not offer the protection of<br />

single-row windbreaks every 600 feet.<br />

However, SCS endorses their use in<br />

combination with other soil conservation<br />

methods.)<br />

"Most farmers in the two counties<br />

have begun a program of minimum<br />

tillage or mulch tillage in an effort to<br />

protect the soil," said Adelman. One<br />

landowner, Joe Gottward of Rice,<br />

moved part of his windbreak out of<br />

the way of his center pivot system and<br />

replanted the trees elsewhere. Other<br />

farmers have attempted to replant, but<br />

dry weather in 1975 and 1976 killed<br />

the young trees. Farmers indicate that,<br />

if they receive enough snow this winter,<br />

they will try again next spring.<br />

Many soil experts believe that windbreaks<br />

not only will prevent wind<br />

erosion on an irrigated field, but will<br />

make the unit more efficient. Water<br />

can be distributed better with less<br />

evaporation if a windbreak adjoins the<br />

pivot system.<br />

Irrigation isn't the only cause of<br />

windbreak removal. In the Red River<br />

Valley, windbreaks of Siberian elm<br />

planted about 15 years ago are now<br />

dying. "The fungus has been isolated,<br />

but it is a secondary cause of death,"<br />

said Scottie Scholten, University of<br />

Minnesota College of Forestry professor.<br />

"The trees have been weakened<br />

by annual crop spraying."<br />

John Hultgren, SCS Woodland Conservationist<br />

in Minnesota, agrees that<br />

crop spray may damage windbreaks of<br />

Siberian elm. "Monoculture is always a<br />

problem," he said. "Siberian elm<br />

looked like the perfect tree, so that<br />

was all that was planted. Today we<br />

encourage a variety of trees in a<br />

shelterbelt, such as a mixture of Siberian<br />

elm, green ash, and cottonwood.<br />

This decreases the likelihood of<br />

disease and insect infestation as well as<br />

the chance of crop spray wiping out<br />

the entire shelterbelt."<br />

The SCS, U.S. Forest Service Extension<br />

Service, and the University of<br />

Minnesota Experiment Stations are<br />

constantly searching for new seedstock<br />

and alternative species to use in field<br />

windbreaks. "We are now looking at a<br />

seed source which will give us a ponderosa<br />

pine with more upright<br />

branches for better snow distribution<br />

across the field," said Scholten. "This<br />

)ANUA RY —FEBRUARY 1978 39

is an important tree in western Minnesota<br />

because of its ability to grow well<br />

in prairie soils."<br />

Another problem faced by owners<br />

of field windbreaks is the replacement<br />

of dying or damaged trees. Old trees<br />

which no longer provide adequate soil<br />

protection may cause the farmer to see<br />

complete removal of the windbreak as<br />

his only option. But there are others.<br />

Replacing all or part of the tree line<br />

can be done over a period of time by:<br />

1) interspersing old trees with young;<br />

2) beginning a second row of young<br />

trees behind a mature row; 3) cutting<br />

down the original growth so it will<br />

grow back from the stumps. "Many<br />

hardwood (deciduous) trees and<br />

shrubs will send out sprouts from the<br />

stump," advises Hultgren. "Simply<br />

choose the straightest or healthiest<br />

looking stem and trim away the rest.<br />

Such regrowth can quickly replace the<br />

trees cut down."<br />

Inventory. The Soil Conservation<br />

Service (SCS) is currently inventorying<br />

shelterbelts in the nation's five major<br />

windbreak states: Kansas, Nebraska,<br />

Oklahoma, and North and South<br />

Dakota. The nine-month study is in<br />

response to a 1975 General<br />

Accounting Office (GAO) report calling<br />

for action to discourage removal of<br />

windbreaks in the Great Plains. Using<br />

aerial photographs, the study is accumulating<br />

up-to-date information on<br />

the number of field windbreaks in the<br />

region, number removed during recent<br />

years, and reasons for their removal.<br />

William Lloyd, Chief Forester for<br />

the SCS (Washington, D.C.), believes<br />

that too much emphasis has been<br />

placed on just the erosion control<br />

benefit of windbreaks. "With the introduction<br />

of minimum tillage, annual<br />

grasses, stripcropping, and other forms<br />

of intensive soil management, windbreaks<br />

are no longer a necessity for<br />

short term erosion control," he said.<br />

"Instead, the biggest losers when shelterbelts<br />

are removed are wildlife habitat<br />

and recreational opportunities.<br />

"The problem is," he continued,<br />

"there is no economic incentive to<br />

cause the farmer to use the land for<br />

shelterbelts when he could use it for<br />

cash crops."<br />

Fortunately, Minnesota is one of<br />

the leading states in planting trees for<br />

field and farmstead windbreaks. In<br />

1976, landowners planted nearly onehalf<br />

million trees for field windbreaks,<br />

offering more than 288 miles of protection.<br />

This increased to 396 miles of<br />

windbreaks planted in 1977, despite<br />

advances in irrigation. This is encouraging<br />

proof that windbreaks are<br />

not a thing of the past, at least in<br />

Minnesota. Interest in the many benefits<br />

of windbreaks remains high and<br />

their continued existence appears certain.<br />

•<br />

Jim Ruen is an Editorial Assistant for<br />

the USDA Soil Conservation Service<br />

in St. Paul.<br />

40 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER