summer 07 / 20:2 - Grand Canyon River Guides

summer 07 / 20:2 - Grand Canyon River Guides

summer 07 / 20:2 - Grand Canyon River Guides

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Evolving Landscapes, Stream Wars, and the<br />

Darwinian Survival of the Fittest<br />

In previous “Letters From the <strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong>,” I<br />

have attempted to outline the various ideas on how<br />

and when the <strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong> came to be, together<br />

with the facts that have a bearing on the problem and<br />

must be taken into account (but often are not) by any<br />

theory that aspires to respectability. Whatever the theories,<br />

the <strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong> is there, vast and mysterious. So,<br />

it not only can exist, it does exist, no matter how much<br />

we may argue about how this happened. This now gives<br />

us leave to start having fun by looking at the happenings<br />

within the <strong>Canyon</strong> once it had developed into something<br />

much like what we see today—roughly the past<br />

one to one-and-a-half million years. It is within this<br />

interval that we can delineate with some degree of confidence<br />

the events that have led to what is there now, and<br />

the processes by which this has happened. And it is also<br />

near the very end of this interval that we start seeing the<br />

<strong>Canyon</strong> interact with that strange and self-important<br />

bipedal primate, Homo, which is so pleased to call itself<br />

sapiens.<br />

We would be remiss, however, if we were to do these<br />

things without first exploring several interesting lessons<br />

that issue from the observations that have been made<br />

and the intellectual turmoil that has occurred in<br />

attempting to solve the great dilemma. This is the<br />

subject of this “Letter.”<br />

Evolving Landscapes<br />

We humans know that the landscape<br />

around us generally changes little, if<br />

at all, within the time we are there<br />

to observe it. It is natural, then, for<br />

us to project this immutability to<br />

intervals of time much longer than<br />

our admittedly short life span: what<br />

is there now must have been there<br />

thousands, hundreds of thousands,<br />

even millions of years ago. “The<br />

eternal hills,” and so on. This may be<br />

perfectly acceptable in the domain of<br />

poetry, but it is not acceptable in the<br />

field of science, where not taking<br />

into account the rapid evolution of<br />

landscape can lead to mistakes such<br />

as using the present-day landscape to<br />

develop theories on the origin of the<br />

<strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong> several millions of<br />

years ago. It is useful, then, to see<br />

how this landscape has changed in<br />

the past several million years during<br />

which the <strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong> was born.<br />

Today, the region surrounding the <strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong> is<br />

underlain principally by the Permian Kaibab Limestone,<br />

the cream-colored rimrock of the <strong>Canyon</strong>. The Kaibab is<br />

tough and hard to erode in a dry climate, so erosion<br />

slows down greatly when it has worked its way down to<br />

the top of that unit. Meanwhile, rocks above the<br />

Kaibab, which are much softer, get swept away. The end<br />

result is that today’s topographic surface coincides with<br />

the top of the Kaibab over wide areas, resulting in a<br />

subdued landscape that slopes gently northeast because<br />

that is the regional dip, or slope, of the Paleozoic strata<br />

of which the Kaibab is part. This landscape is interrupted<br />

only where some geologic feature such as a fold<br />

disturbs the otherwise simple arrangement of the strata.<br />

But even there the topographic surface mostly follows<br />

the top of the Kaibab Limestone. For example, a topographic<br />

feature—the Kaibab Plateau—follows exactly a<br />

geologic one—the Kaibab Anticline (or dome), an uparching<br />

of the strata.<br />

Has this always been so Not at all. To begin with,<br />

we know that even a short time ago, geologically, the<br />

region where now the Kaibab Limestone forms the<br />

surface rock was underlain instead by the Triassic<br />

Moenkopi Formation, the brick-red sandstone that crops<br />

out near the Lees Ferry boat ramp. We know this<br />

because lavas that have been dated and are not very old<br />

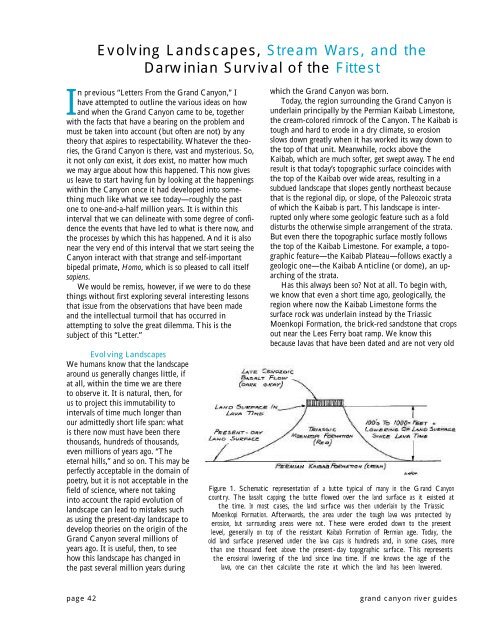

Figure 1. Schematic representation of a butte typical of many in the <strong>Grand</strong> <strong>Canyon</strong><br />

country. The basalt capping the butte flowed over the land surface as it existed at<br />

the time. In most cases, the land surface was then underlain by the Triassic<br />

Moenkopi Formation. Afterwards, the area under the tough lava was protected by<br />

erosion, but surrounding areas were not. These were eroded down to the present<br />

level, generally on top of the resistant Kaibab Formation of Permian age. Today, the<br />

old land surface preserved under the lava caps is hundreds and, in some cases, more<br />

than one thousand feet above the present-day topographic surface. This represents<br />

the erosional lowering of the land since lava time. If one knows the age of the<br />

lava, one can then calculate the rate at which the land has been lowered.<br />

page 42<br />

grand canyon river guides