Conserving Biodiversity in Brigalow Regrowth - School of ...

Conserving Biodiversity in Brigalow Regrowth - School of ...

Conserving Biodiversity in Brigalow Regrowth - School of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PARTNERS<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Clive McAlp<strong>in</strong>e<br />

c.mcalp<strong>in</strong>e@uq.edu.au<br />

Clive is a landscape ecologist at The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland. He<br />

studies the effect <strong>of</strong> landscape change and climate change on native flora<br />

and fauna, and the feedbacks <strong>of</strong> landscape change on climate.<br />

Dr Mart<strong>in</strong>e Maron<br />

m.maron@uq.edu.au<br />

Mart<strong>in</strong>e is a landscape ecologist at The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland with<br />

a particular <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> biodiversity management <strong>in</strong> human-dom<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

landscapes, bird community dynamics and conservation.<br />

Dr Ge<strong>of</strong>frey C. Smith<br />

Ge<strong>of</strong>f.Smith@derm.qld.gov.au<br />

Ge<strong>of</strong>frey is a Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal Zoologist with the Queensland Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Environment and Resource Management. His research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

the fauna and ecosystems <strong>of</strong> brigalow landscapes and fire <strong>in</strong> this system.<br />

Dr Michiala Bowen<br />

michiala.bowen@uqconnect.edu.au<br />

Michiala is a landscape ecologist at The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland. She<br />

studies the effects <strong>of</strong> habitat loss and fragmentation on brigalow wildlife<br />

and the values <strong>of</strong> brigalow regrowth for landscape restoration.<br />

Dr Leonie Seabrook<br />

l.seabrook@uq.edu.au<br />

Leonie is a landscape ecologist at The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland. She<br />

studies the patterns and causes <strong>of</strong> habitat loss and fragmentation over<br />

time.<br />

Dr John Dwyer<br />

j.dwyer2@uq.edu.au<br />

John is a plant ecologist at the University <strong>of</strong> Western Australia. His PhD<br />

research was undertaken at The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland and focused on<br />

the restoration and carbon potential <strong>of</strong> brigalow regrowth.<br />

Sarah Butler<br />

sarah.butler@uq.edu.au<br />

Sarah is a PhD student <strong>in</strong> landscape ecology at The University <strong>of</strong><br />

Queensland, research<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>teractive effects <strong>of</strong> land use, climate<br />

and biological <strong>in</strong>vasions on the biodiversity <strong>of</strong> fragmented brigalow<br />

ecosystems.<br />

Cameron Graham<br />

c.graham@uq.edu.au<br />

Cameron is a PhD student at The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland. He is<br />

currently <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g how feral cats and red foxes are <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

agricultural landscape <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt South.<br />

WILLIAM GOULDING<br />

w.gould<strong>in</strong>g@uq.edu.au<br />

2<br />

Will is a field ecologist with The University <strong>of</strong> Queensland; he has<br />

extensive experience with fauna surveys <strong>in</strong> the Australasian region. He<br />

conducted many <strong>of</strong> the bird and reptile field surveys that contribute to this<br />

booklet and provided many <strong>of</strong> the photographic images.

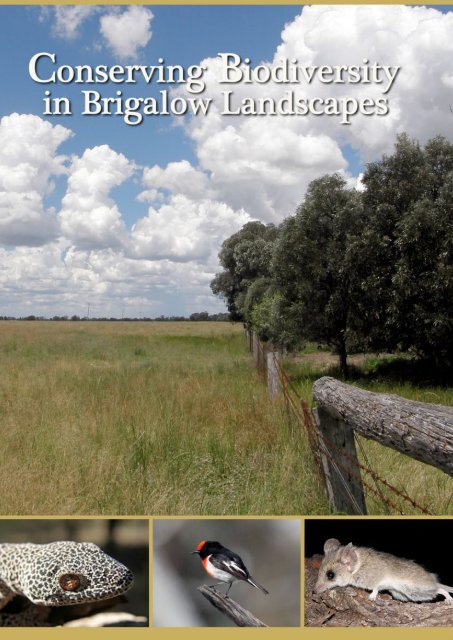

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Foreword 4<br />

Introduction 5<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> landscapes 6<br />

History: transform<strong>in</strong>g the brigalow 7<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> woodland: why is it important? 9<br />

Threats to <strong>Brigalow</strong> 10<br />

Climate, variability and change 11<br />

Scales <strong>of</strong> habitat management 12<br />

How much vegetation? 14<br />

<strong>Regrowth</strong> is important 15<br />

Manag<strong>in</strong>g regrowth: to th<strong>in</strong> or not to th<strong>in</strong>? 16<br />

Roadside treel<strong>in</strong>es: are they too narrow? 17<br />

Key habitat features 18<br />

Problem species 19<br />

Iconic species 20<br />

Types <strong>of</strong> landscapes 23<br />

Fauna species list 24<br />

Quick reference guide 26<br />

Useful contacts and resources 27<br />

Further read<strong>in</strong>g 27<br />

3

Foreword<br />

Times change.<br />

In 1960 when I graduated B. Agr.<br />

Science from the University <strong>of</strong><br />

Queensland the prevail<strong>in</strong>g ethos was<br />

that unproductive lands should be<br />

developed, as a priority. The brigalow<br />

lands were at the top <strong>of</strong> the list.<br />

New methods <strong>of</strong> clear<strong>in</strong>g us<strong>in</strong>g heavy<br />

mach<strong>in</strong>ery and aerial spray<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

potent herbicides gave momentum<br />

to the attack. Back then the sheer<br />

immensity <strong>of</strong> the brigalow lands<br />

made it difficult to conceive <strong>of</strong> a time<br />

when there would be concern for the<br />

remnants <strong>of</strong> these once dist<strong>in</strong>ctive<br />

landscapes. But with<strong>in</strong> a few decades<br />

less than ten per cent <strong>of</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

cover rema<strong>in</strong>ed. Even this pitiful total<br />

conceals the true picture. Very few<br />

large (>1000 ha.) tracts rema<strong>in</strong> and<br />

even fewer are <strong>in</strong> reserves.<br />

What is more these do not provide a<br />

representative sample <strong>of</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

great diversity <strong>of</strong> brigalow landscapes.<br />

The best developed brigalow<br />

vegetation on the most productive<br />

sites was targeted early and <strong>of</strong> this<br />

virtually noth<strong>in</strong>g rema<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> what is left, along roads<br />

and <strong>in</strong> small paddock remnants,<br />

is conservation by default; it was<br />

deemed unavailable or unsuitable<br />

for productive use. The loss <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity has been <strong>in</strong>calculable but,<br />

as this booklet affirms, not all is lost.<br />

I have had a life long association and<br />

appreciation <strong>of</strong> brigalow landscapes.<br />

Firstly, around my grandparents’<br />

property <strong>in</strong> the Central Highlands<br />

west from Emerald; later <strong>in</strong> the longsettled<br />

scrublands <strong>of</strong> the Lockyer and<br />

Fassifern valleys, eastern Darl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Downs and the Burnett Valley <strong>in</strong><br />

south-east Queensland. By my late<br />

teens I had traversed most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt Bioregion.<br />

Then <strong>in</strong> the early 1960s I consider<br />

myself fortunate to have been a<br />

member <strong>of</strong> the CSIRO teams that<br />

conducted land resource surveys<br />

that preceded the massive clear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Lands Development<br />

Scheme <strong>in</strong> the Fitzroy and Belyando<br />

catchments. These surveys focused<br />

on descriptions <strong>of</strong> land forms, soils<br />

and vegetation and subsequent<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> the potential for<br />

agricultural, pastoral and forestry<br />

production. Conservation was not<br />

a focus, but attention was drawn<br />

to the need to reserve adequate<br />

representative samples <strong>of</strong> the<br />

landscapes described, as well as<br />

specific examples <strong>of</strong> unique, unusual<br />

and restricted areas <strong>of</strong> vegetation.<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> the day<br />

steadfastly ignored this advice and<br />

by the time later Governments took<br />

action, it was too little and too late.<br />

Active brigalow regrowth has been<br />

a scourge for the settler, but it does<br />

provide an opportunity as well as<br />

a challenge. It can provide a basis<br />

for renewal <strong>of</strong> wildlife habitat, for<br />

enhanc<strong>in</strong>g connectivity across<br />

landscapes and for develop<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

potentially valuable carbon s<strong>in</strong>k.<br />

Reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g strips <strong>of</strong> regrowth to<br />

provide shade and shelter from the<br />

hot north-west w<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> summer and<br />

the cold south-westerlies <strong>of</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter<br />

for both crops and livestock can be a<br />

plus. In fact, complete farm redesign<br />

to take account <strong>of</strong> natural contours<br />

and dra<strong>in</strong>age l<strong>in</strong>es can overcome<br />

the tyranny <strong>of</strong> the theodolite which<br />

has imposed straight l<strong>in</strong>es on nonl<strong>in</strong>ear<br />

landscapes. As the research<br />

reported <strong>in</strong> this booklet shows even<br />

young brigalow regrowth has some<br />

value for wildlife, with the number<br />

<strong>of</strong> species <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g with age.<br />

Reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g but th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> regrowth<br />

can have benefits and this has been<br />

addressed <strong>in</strong> this publication.<br />

All those who have tackled<br />

development <strong>of</strong> brigalow landscapes<br />

have my respect, but I have a deep<br />

sadness for the natural world that has<br />

been lost.<br />

What can be done to stem the loss and<br />

return the landscape to a better balance?<br />

Because much <strong>of</strong> the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g brigalow<br />

vegetation is <strong>in</strong> private ownership, on<br />

farms, ensur<strong>in</strong>g a balance between<br />

production and conservation <strong>of</strong> flora<br />

and fauna is very much a matter for the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual landholder.<br />

The years <strong>of</strong> focused research that are<br />

summarized <strong>in</strong> this booklet provide<br />

useful guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the plann<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

management <strong>of</strong> remnant brigalow<br />

vegetation. F<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>centives, such<br />

as taxation concessions, may be<br />

necessary for landholders to take up<br />

these recommendations. The irony is<br />

that taxation concessions were used<br />

to stimulate the massive clearance <strong>of</strong><br />

brigalow <strong>in</strong> the first place!<br />

Henry Nix<br />

Henry Nix is an Emeritus Pr<strong>of</strong>essor at<br />

Australian National University with over<br />

30 years experience study<strong>in</strong>g Australian<br />

landscapes.<br />

4

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> (Acacia harpophylla) is a dist<strong>in</strong>ctive silver-foliaged<br />

shrub or tree – one <strong>of</strong> the 980 species <strong>of</strong> Acacia <strong>in</strong> Australia.<br />

The brigalow tree is commonly the dom<strong>in</strong>ant species <strong>of</strong> a<br />

range <strong>of</strong> open forests and woodlands, which are collectively<br />

referred to as brigalow woodlands <strong>in</strong> this booklet. <strong>Brigalow</strong><br />

woodlands are found mostly west <strong>of</strong> the Great Divid<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Range, stretch<strong>in</strong>g north almost to Townsville, south to<br />

Narrabri <strong>in</strong> New South Wales, and west to Bourke on the<br />

Darl<strong>in</strong>g River and Blackall <strong>in</strong> central western Queensland.<br />

They occur mostly on deep crack<strong>in</strong>g clay soils with a<br />

microrelief pattern referred to as gilgai or melon holes which<br />

<strong>in</strong>termittently fill with water.<br />

Scientific understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> brigalow landscapes<br />

and ecosystems lags beh<strong>in</strong>d that <strong>of</strong> many woodland<br />

ecosystems <strong>in</strong> southern Australia.<br />

Over the past 8 years, a team <strong>of</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Queensland<br />

researchers have been conduct<strong>in</strong>g field studies <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt South.<br />

This booklet summarises the ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> these studies.<br />

We aim to provide <strong>in</strong>formation relevant to farmers and<br />

other natural resource managers look<strong>in</strong>g to manage native<br />

vegetation for wildlife habitat with<strong>in</strong> brigalow production<br />

landscapes.<br />

Although our focus is predom<strong>in</strong>antly on southern <strong>Brigalow</strong><br />

Belt landscapes, many <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this<br />

booklet are also relevant for the northern <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt.<br />

5

<strong>Brigalow</strong> Landscapes<br />

The <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt is an important region nationally for its agricultural production and for its rich diversity <strong>of</strong> native<br />

fauna and flora. For most <strong>of</strong> the 20th century, the focus <strong>of</strong> government was the agricultural development <strong>of</strong> the<br />

region.<br />

More recently, as the Australian community has become<br />

more aware <strong>of</strong> environmental problems, this focus has<br />

shifted to f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g a more susta<strong>in</strong>able balance between<br />

conservation and production.<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> remnant vegetation is now protected <strong>in</strong><br />

Queensland and New South Wales and listed as nationally<br />

threatened under the Environment Protection and<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> Conservation Act 1999. However, this alone<br />

is unlikely to ensure the long-term viability <strong>of</strong> native bird,<br />

reptile and mammal populations, many <strong>of</strong> which are <strong>in</strong><br />

serious decl<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

To susta<strong>in</strong> our native flora and fauna it is important to th<strong>in</strong>k<br />

<strong>of</strong> whole landscapes, rather than just <strong>in</strong>dividual patches or<br />

even species. Landscapes are best observed from a light<br />

plane or helicopter and are made up <strong>of</strong> the mix <strong>of</strong> remnant<br />

and regrowth woodland patches, paddocks <strong>of</strong> crops and<br />

pastures and farm dams. Many brigalow landscapes have<br />

less than 10% native vegetation rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, with patches<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten occurr<strong>in</strong>g as narrow l<strong>in</strong>ear strips left along fencel<strong>in</strong>es<br />

and roadsides.<br />

Nevertheless, brigalow landscapes have one important<br />

advantage: retention <strong>of</strong> naturally regenerat<strong>in</strong>g or regrowth<br />

vegetation that occurs <strong>in</strong> formerly cleared areas is a lowcost<br />

and highly efficient way to restore habitat.<br />

Although not all regrowth is protected (except under some<br />

provisions <strong>in</strong> Queensland and Commonwealth legislation),<br />

landholders are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> its potential to<br />

contribute to farm <strong>in</strong>come through: a) its value as a carbon<br />

s<strong>in</strong>k, and b) the delivery <strong>of</strong> ecological services for which<br />

stewardship payments are made.<br />

To successfully manage brigalow landscapes for conservation as well as production, we need<br />

to understand how the region’s fauna are affected by how humans <strong>in</strong>fluence the landscape.<br />

This booklet answers a set <strong>of</strong> the most important questions on how to manage brigalow<br />

vegetation for conserv<strong>in</strong>g and restor<strong>in</strong>g wildlife <strong>in</strong> the region, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

1. How much vegetation is enough?<br />

2. What are the priority areas to restore?<br />

3. How important are l<strong>in</strong>ear patches?<br />

4. How important is connectivity among patches?<br />

5. How important is regrowth <strong>of</strong> different ages and how can we manage it for<br />

biodiversity?<br />

6. What management actions would help to <strong>in</strong>crease the diversity <strong>of</strong> animal species and their<br />

abundance?<br />

6<br />

* See page 26 for a quick reference guide with practical answers to these questions.

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

History: Transform<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Brigalow</strong><br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> is an aborig<strong>in</strong>al name adopted by white settlers who pushed north and <strong>in</strong>land from the Hunter Valley <strong>in</strong> the<br />

1830s and 1840s.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the first references to brigalow was <strong>in</strong> Ludwig Leichhardt’s journal <strong>of</strong> his expedition from Moreton Bay to Port<br />

Ess<strong>in</strong>gton, published <strong>in</strong> 1847:<br />

“After hav<strong>in</strong>g past the great pla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the Condam<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

between Coxcens[uncerta<strong>in</strong>?] Station, Fimba and Rupells<br />

Stations we entered <strong>in</strong>to a country, which was alternately<br />

covered with f<strong>in</strong>e open forestland, well grassed and fit<br />

for cattle and horses breed<strong>in</strong>g – and with long stretches<br />

<strong>of</strong> almost impassable Bricklow scrub, so called from the<br />

Bricklow (a species <strong>of</strong> acacia) be<strong>in</strong>g one <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal<br />

components.<br />

Open Myalscrub was frequent, particularly along the<br />

Condam<strong>in</strong>e. Though the Bricklow scrubs were frequently <strong>of</strong><br />

great length and breadth, I do not th<strong>in</strong>k that they ever form<br />

un<strong>in</strong>terrupted l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> more than 20–30 miles so that they<br />

allways allow to be skirted.<br />

The frequency <strong>of</strong> these scrubs however would render the<br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> stations unadviseable, as they not only<br />

allow a secure retreat to hostile blackfellows, but to wild<br />

cattle.”<br />

– (Report <strong>of</strong> the Expedition <strong>of</strong> L. Leichhardt Esq. From<br />

Moreton Bay to Port Ess<strong>in</strong>gton)<br />

Early settlement<br />

The early European settlers <strong>of</strong> the Darl<strong>in</strong>g Downs faced a<br />

multitude <strong>of</strong> challenges <strong>in</strong> transform<strong>in</strong>g the land. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

1860s and 70s, as people <strong>in</strong>itially attempted to clear forests<br />

for pasture and agriculture, they cursed the dense brigalow<br />

woodlands that defied the axe, fenc<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>of</strong>f as waste<br />

country.<br />

They quickly realised the ability <strong>of</strong> brigalow to reappear as<br />

dense sucker regrowth, which was even more difficult to<br />

remove.<br />

A series <strong>of</strong> droughts affected much <strong>of</strong> eastern Australia from<br />

the 1880s through to 1902 culm<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Federation<br />

drought <strong>of</strong> 1901–02, when up to 90% <strong>of</strong> livestock on<br />

some properties died and livestock numbers halved <strong>in</strong> the<br />

southern <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g these difficult times, many settlers <strong>of</strong> brigalow<br />

country abandoned their land and moved to towns to f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

work.<br />

7

Between the Wars<br />

After WWI, development <strong>of</strong> the southern <strong>Brigalow</strong><br />

Belt progressed slowly, due largely to the resilient<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> the plant and the lack <strong>of</strong> technology to deal<br />

with its defences.<br />

Between 1880 and 1934, the southern <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt<br />

was <strong>in</strong>vaded by prickly pear (Opuntia species).<br />

The successful control <strong>of</strong> prickly pear <strong>in</strong> the early<br />

1930s meant that development <strong>of</strong> brigalow lands<br />

began aga<strong>in</strong>. At first, development was relatively<br />

slow due to a lack <strong>of</strong> mechanisation.<br />

8<br />

The settlers were a hardy lot and by the outbreak <strong>of</strong><br />

WWII large blocks <strong>of</strong> brigalow <strong>in</strong> southern districts<br />

like Tara had been cleared by axe, burn<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

<strong>in</strong>tensive sheep graz<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Broad-scale clear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g WWII, technological change <strong>in</strong>creased the<br />

pace <strong>of</strong> brigalow development.<br />

One famous land clear<strong>in</strong>g contractor, Joh Bjelke-<br />

Peterson – later Premier <strong>of</strong> Queensland – pioneered<br />

a technique for quickly clear<strong>in</strong>g scrub by connect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a heavy anchor cha<strong>in</strong> between two bulldozers.<br />

Mechanised clear<strong>in</strong>g soon became a common<br />

practice and by 1954 the most determ<strong>in</strong>ed efforts to<br />

clear brigalow woodlands began.<br />

In the eight years between 1953 and 1961, 1 million<br />

ha were cleared at a rate <strong>of</strong> 120,000 ha per year.<br />

In 1962, The <strong>Brigalow</strong> and Other Lands Development<br />

Act was passed. Under the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Development<br />

Scheme, approximately 2 million ha was allocated<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Bauh<strong>in</strong>ia, Taroom and Duar<strong>in</strong>ga districts, with<br />

a further 2.4 million ha <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt North.<br />

Properties were to be large enough to stock 1,000<br />

cattle. State and Commonwealth governments<br />

provided loans <strong>of</strong> up to $60,000 for settlers to cover<br />

development costs, plus pay<strong>in</strong>g for the construction<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1,200 km <strong>of</strong> development roads.<br />

By the 1970s, most <strong>of</strong> the brigalow scrub had<br />

disappeared. Vast areas <strong>of</strong> sucker regrowth were<br />

controlled by aerial spray<strong>in</strong>g with 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D,<br />

burn<strong>in</strong>g and mechanical means, <strong>in</strong> preparation for<br />

improved pastures and cropp<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Sheep numbers decl<strong>in</strong>ed markedly matched by a rise<br />

<strong>in</strong> cattle numbers and the area under crops.<br />

The rise <strong>in</strong> cropp<strong>in</strong>g was l<strong>in</strong>ked to a severe decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong><br />

cattle prices <strong>in</strong> the 1970s and to the more effective<br />

control <strong>of</strong> <strong>Brigalow</strong> regrowth us<strong>in</strong>g blade plough<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

whereby the roots were cut <strong>of</strong>f under the soil.<br />

Lynelle, Amy, Jemma & Warren Urquhart on Warrowa<br />

Warrowa<br />

Warren and Lynelle Urquhart, owners <strong>of</strong> Warrowa, 26 km<br />

west <strong>of</strong> Moonie, believe <strong>in</strong> the values <strong>of</strong> biodiversity and try to<br />

manage their cropp<strong>in</strong>g and cattle graz<strong>in</strong>g for both economic<br />

and environmental long term susta<strong>in</strong>ability.<br />

What is now “Warrowa” (3,600 ha) was part <strong>of</strong> “Ulupna”<br />

(29,000 acres), a prickly pear ballot that was drawn <strong>in</strong> 1934 by<br />

Archibald Telford and worked by him and his brother, George.<br />

In 1945 George took up Warrowa as his own and set about<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g the property <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g native brigalow vegetation<br />

retention (both remnant and regrowth) mostly as shade l<strong>in</strong>es<br />

around each paddock, which was cont<strong>in</strong>ued by the Urquharts<br />

when they took over <strong>in</strong> 2000.<br />

“About 20% <strong>of</strong> Warrowa is reta<strong>in</strong>ed as both remnant and<br />

regrowth brigalow mostly <strong>in</strong> shade l<strong>in</strong>es that border each<br />

paddock, creat<strong>in</strong>g corridors that stretch throughout the length<br />

& breadth <strong>of</strong> the property. Another 15% <strong>of</strong> Warrowa is mixed<br />

eucalypt woodland on a ridge <strong>of</strong> red, sandy loam runn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

through the property. We see these wooded areas as valuable<br />

assets for stock shelter<strong>in</strong>g from temperature extremes,<br />

for w<strong>in</strong>d breaks for crops and pastures and reduction <strong>in</strong><br />

evapotranspiration <strong>of</strong> soil moisture, reduc<strong>in</strong>g dra<strong>in</strong>age below<br />

pasture root zones to keep salt levels where they should be, as<br />

well as important habitat for native flora and fauna.<br />

We know that the fauna (e.g., crows, bats, and other <strong>in</strong>sect<br />

eaters) play an important role <strong>in</strong> pest m<strong>in</strong>imisation <strong>in</strong> our crops<br />

and pastures. Often there can be flocks <strong>of</strong> 200 crows beh<strong>in</strong>d<br />

the tractor devour<strong>in</strong>g all the mice and grubs they can!<br />

We realise that the shade l<strong>in</strong>es could theoretically be razed to<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease the area <strong>of</strong> crops or pasture grown now, which would<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease short term cash flow, but we believe that this practice<br />

would be detrimental to the long term health <strong>of</strong> this land and<br />

therefore also to the economic susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>of</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g here.<br />

It’s important to allot real value to the natural environment.<br />

Just because humans aren’t us<strong>in</strong>g it for a direct and immediate<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ancial benefit at present, doesn’t mean it is “wasted”.<br />

We’re plann<strong>in</strong>g for the long term health and susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>of</strong><br />

Warrowa, which isn’t just ours or our children’s tenure on the<br />

land, but hopefully for many, many generations. We need to<br />

make sure we can feed people <strong>in</strong>to the future so we try to run<br />

our farm bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> an economically and environmentally<br />

balanced way.”<br />

Warren & Lynelle Urquhart, January 2011

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> Woodland:<br />

Why is it so important?<br />

Popular op<strong>in</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> brigalow woodlands have changed considerably over the last 50–100 years. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the days<br />

<strong>of</strong> heavy prickly pear <strong>in</strong>festation brigalow was viewed as hav<strong>in</strong>g no use for agricultural production. However, these<br />

views soon changed when prickly pear was controlled and the productivity <strong>of</strong> cleared brigalow lands was realised.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1950s, 60s, 70s and <strong>in</strong>to the 1980s, the most valued brigalow lands were those that were kept clean <strong>of</strong><br />

any natural vegetation.<br />

It is only <strong>in</strong> the last two decades, after most <strong>of</strong> the brigalow<br />

woodlands have been permanently lost, that there has been<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g recognition <strong>of</strong> their ecological value as home to<br />

a rich diversity <strong>of</strong> fauna and flora. In fact, the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt<br />

bioregion is recognised as a national biodiversity hotspot.<br />

For example, the bioregion supports more resident bird<br />

species than any other bioregion <strong>in</strong> Australia. This diversity<br />

arises from the east to west overlap <strong>of</strong> species common to<br />

coastal and arid zone environments, and the north to south<br />

overlap <strong>of</strong> tropical and temperate species.<br />

they support and you will be rewarded with the chorus <strong>of</strong><br />

birdsong fill<strong>in</strong>g the air. If there has been recent ra<strong>in</strong> you may<br />

also hear and see frogs tak<strong>in</strong>g advantage <strong>of</strong> the conditions<br />

and may be lucky to see species like the t<strong>in</strong>y crucifix toad<br />

with its bright yellow, red and green colours. Many <strong>of</strong><br />

the reptiles and small mammals are hard to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> these<br />

woodlands, but a night time walk with a torch may reveal<br />

the bright eye-sh<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> geckos and you may be lucky to<br />

encounter nocturnal snakes <strong>in</strong> search <strong>of</strong> a feed, like the<br />

woma python.<br />

The common birds <strong>of</strong> the brigalow woodlands <strong>in</strong>clude many<br />

species <strong>in</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e further south, such as yellow thornbills,<br />

grey-crowned babblers and eastern yellow rob<strong>in</strong>s. Large<br />

groups <strong>of</strong> apostlebirds and white-w<strong>in</strong>ged choughs can<br />

make a walk <strong>in</strong> brigalow woodland a noisy affair. Spotted<br />

bowerbirds are seen more rarely. Reptiles are also well<br />

represented <strong>in</strong> the region, with several species that occur<br />

nowhere else, like the golden-tailed gecko and brigalow<br />

scaly-foot. Other threatened reptile species <strong>in</strong>clude the<br />

common death adder and the yakka sk<strong>in</strong>k.<br />

Native mammals <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g koalas, possums and gliders,<br />

kangaroos and wallabies, bandicoots and small carnivores<br />

all occur <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt. T<strong>in</strong>y but ferocious carnivorous<br />

marsupials like the common and narrow-nosed planigales<br />

and common dunnarts, despite their names, are now<br />

rarely encountered. Bats are also rarely seen up close,<br />

but brigalow woodlands support many species <strong>of</strong> the t<strong>in</strong>y<br />

nocturnal <strong>in</strong>sectivorous ‘microbats’, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the little pied<br />

bat and the yellow-bellied sheathtail bat. Wallabies and<br />

kangaroos are more commonly encountered, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g red,<br />

eastern grey and western grey kangaroos, wallaroos, and<br />

black-striped, red-necked and whiptail wallabies.<br />

It is hard to imag<strong>in</strong>e what early settlers explor<strong>in</strong>g vast<br />

stands <strong>of</strong> brigalow woodland would have encountered. It<br />

is rare these days to enter a patch <strong>of</strong> brigalow woodland<br />

and not be able to see through the trees to the other side—<br />

nowadays patches are <strong>of</strong>ten narrow and the understorey<br />

has been opened up by graz<strong>in</strong>g stock.<br />

Some idea <strong>of</strong> the pre-European vegetation conditions<br />

can be ga<strong>in</strong>ed from a walk <strong>in</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the few large stands<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> national parks like Err<strong>in</strong>gibba or Southwood.<br />

If you walk far enough <strong>in</strong>to the woodland you can quickly<br />

feel disoriented as the woodland looks the same <strong>in</strong> every<br />

direction. It is not hard to sense why the early settlers felt<br />

uneasy <strong>in</strong> these woodlands.<br />

If you take an early morn<strong>in</strong>g walk through a remnant <strong>of</strong><br />

brigalow woodland you will also realise how much life<br />

TOP: Golden-tailed Gecko, BOTTOM (L-R): Stripe-faced Dunnart and<br />

Grey-crowned Babbler. IMAGES: WILL GOULDING<br />

9

threats to brigalow<br />

Although the brigalow ecological community was orig<strong>in</strong>ally extensive <strong>in</strong> Queensland and northern New South<br />

Wales, less than 10% is left.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the brigalow is <strong>in</strong> small patches, shade-l<strong>in</strong>es and<br />

roadside strips. Because <strong>of</strong> this, and ongo<strong>in</strong>g threats to<br />

rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g brigalow, the ecological community is listed<br />

as nationally threatened under the Commonwealth<br />

Environment Protection and <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Conservation Act<br />

1999.<br />

Luckily, even relatively small patches <strong>of</strong> brigalow can still<br />

be habitat for many species <strong>of</strong> fauna. The remnant patches<br />

support at least 17 threatened species <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

birds, bats, wallabies and reptiles. Some threatened<br />

species even occupy regrowth brigalow, particularly as it<br />

ages.<br />

Nevertheless, there are still significant threats to rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

brigalow woodland.<br />

Weeds and fire<br />

While there are many weeds that threaten the remnant<br />

brigalow ecosystems, some have potentially disastrous<br />

consequences. In particular, grasses that are useful <strong>in</strong><br />

pasture, such as buffel grass (Cenchrus cilaris) and green<br />

panic (Panicum maximum var. trichoglume), can spread<br />

throughout brigalow remnants, chang<strong>in</strong>g habitat structure<br />

for ground-dwell<strong>in</strong>g fauna and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the risk <strong>of</strong> fire.<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> and most <strong>of</strong> the plant species which grow <strong>in</strong><br />

brigalow woodland are killed by <strong>in</strong>tense fire, so control <strong>of</strong><br />

grassy weeds with<strong>in</strong> and close to brigalow remnants is the<br />

key to their survival. Tree th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and soil disturbance can<br />

help weeds enter brigalow woodland patches, and livestock<br />

can br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> weed seeds. Careful management <strong>of</strong> graz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and its exclusion from <strong>in</strong>tact stands <strong>of</strong> brigalow where<br />

possible can help reduce the risk <strong>of</strong> weed <strong>in</strong>vasion.<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

Overgraz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> shade-l<strong>in</strong>es and clumps <strong>of</strong> trees are valuable<br />

as shelter for livestock. Careful consideration <strong>of</strong> stock<strong>in</strong>g<br />

numbers and livestock camp sites is important to avoid<br />

damage to the woodland understorey. Heavy graz<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

trampl<strong>in</strong>g reduces the value <strong>of</strong> the woodland for wildlife,<br />

and <strong>of</strong>ten encourages undesirable species such as weeds<br />

and feral animals. Rotational graz<strong>in</strong>g regimes and lower<br />

stock<strong>in</strong>g rates both help to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> the value <strong>of</strong> brigalow<br />

woodland for livestock and wildlife.<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

Clear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Even though less than 10% <strong>of</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al brigalow ecosystems<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>, pressure to remove more brigalow cont<strong>in</strong>ues.<br />

Feral animals<br />

Foxes and cats are common <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt, and<br />

can threaten native species (See page 19). Mediumsized<br />

mammals (between 50–500 g) are at most risk from<br />

these predators, and they are also known to take native<br />

reptiles and birds as prey. Pigs cause damage to brigalow<br />

woodlands and adjacent farmland, destroy<strong>in</strong>g young plants<br />

and disturb<strong>in</strong>g the soil.<br />

Controll<strong>in</strong>g pigs, foxes and cats requires a coord<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

approach, preferably among groups <strong>of</strong> neighbours and<br />

ideally across subregions.<br />

10<br />

CAMERON GRAHAM<br />

Sometimes this is for large <strong>in</strong>frastructure, m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and gas<br />

extraction projects, and sometimes it is for smaller-scale<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>of</strong> roads and fences.<br />

Every bit lost has an impact on wildlife – many animals<br />

cannot simply move elsewhere when their habitat is cleared,<br />

as there is nowhere to go that is not already occupied by<br />

other <strong>in</strong>dividuals.<br />

In the longer-term, the tendency <strong>of</strong> brigalow to regrow<br />

presents an opportunity to compensate for losses <strong>of</strong> habitat<br />

that cannot be avoided. Although it is not clear whether the<br />

habitat values <strong>of</strong> mature, remnant brigalow can be entirely<br />

replaced by regrowth as it ages, careful management <strong>of</strong><br />

regrowth vegetation might result <strong>in</strong> new suitable habitat<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g created, which can help to reduce the impacts <strong>of</strong><br />

clear<strong>in</strong>g (see page 15).

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

Climate, VARIABILITY & CHANGE<br />

Climate variability, a critical concern for agricultural production <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt, also affects brigalow<br />

ecosystems. Drought stresses trees and can cause their death, while extreme wet years such as 2010 allow<br />

widespread regeneration <strong>of</strong> native trees, shrubs and grasses.<br />

The 2001–2007 drought was comparable <strong>in</strong> severity and<br />

duration with the Federation drought (1898–1903), the worst<br />

drought on record.<br />

Over the past decade, the variability <strong>in</strong> ra<strong>in</strong>fall is well with<strong>in</strong><br />

the range expected from natural variability for the region<br />

recorded for the 130 years <strong>of</strong> records. However, the recent<br />

drought was hotter and the future climate <strong>of</strong> the region is<br />

projected to be hotter.<br />

Over the past decade, average annual temperature <strong>in</strong> the<br />

region has <strong>in</strong>creased by 0.5 o C. This trend is expected to<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue, with a projected <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> temperature <strong>of</strong> 3–5 o C<br />

by 2070.<br />

For example, the number <strong>of</strong> hot days per year above 35 o C<br />

for Miles is likely to triple from 31 days to 93 days by 2070.<br />

Ra<strong>in</strong>fall is also likely to decl<strong>in</strong>e with a result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

<strong>in</strong> evaporation by 6–15%. The number <strong>of</strong> frost days will<br />

decrease. These changes are well outside the range <strong>of</strong><br />

historical climate variability.<br />

Changes <strong>in</strong> temperature and ra<strong>in</strong>fall will place added<br />

pressures on farm<strong>in</strong>g communities, agricultural production<br />

and brigalow ecosystems. Heatwaves are known to cause<br />

physical stress for wildlife that may result <strong>in</strong> death; koalas<br />

are one example <strong>of</strong> a species that is known to suffer higher<br />

mortality dur<strong>in</strong>g heatwaves.<br />

In addition to the physical stresses <strong>of</strong> high temperatures,<br />

prolonged droughts result <strong>in</strong> lowered food availability.<br />

Stressed plants may fail to flower and produce fruits and<br />

<strong>in</strong>sect prey items may become scarce. In 2006–2007 the<br />

prolonged drought conditions <strong>in</strong> Victorian woodlands<br />

resulted <strong>in</strong> the failure <strong>of</strong> eucalypt trees to flower and the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> nectar-feed<strong>in</strong>g birds decl<strong>in</strong>ed sharply.<br />

Animals liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> fragmented brigalow landscapes will be<br />

particularly vulnerable to the effects <strong>of</strong> hotter and drier<br />

conditions as the fragments <strong>of</strong> habitat are too few and far<br />

between to allow animals to move further afield to f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

scarce resources.<br />

In addition to these pressures, high temperatures and<br />

ra<strong>in</strong>fall deficits will hamper efforts to restore brigalow<br />

landscapes—slow growth rates and die-back will result <strong>in</strong><br />

much longer time periods before regrowth can develop <strong>in</strong>to<br />

mature habitat.<br />

11

Scales <strong>of</strong> Habitat Management<br />

Manag<strong>in</strong>g brigalow woodland for a diverse range <strong>of</strong> fauna requires th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about habitat use at multiple scales.<br />

For example, some animals spend most <strong>of</strong> their lives <strong>in</strong> a small area <strong>of</strong> a hectare or less, but others need to move<br />

over distances <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> kilometres.<br />

A step back:<br />

the whole patch<br />

It is not just what happens <strong>in</strong> the stand<br />

<strong>of</strong> brigalow that is important to the<br />

fauna that live there.<br />

A patch is an area <strong>of</strong> woodland or<br />

forest that has more or less uniform<br />

characteristics and is bounded by a<br />

land-cover type that is very different.<br />

For example, the edge <strong>of</strong> a brigalow<br />

woodland patch might be where it<br />

meets a paddock <strong>of</strong> wheat.<br />

Up close:<br />

the Forest Stand<br />

Just like people, animals need to have<br />

a place they call home, a place that<br />

provides them with shelter from the<br />

elements and from other animals that<br />

might hunt them, a place to sleep and<br />

raise their young.<br />

A home may be as simple as a cavity<br />

under a log, the crevice under some<br />

peel<strong>in</strong>g bark on a brigalow tree, or the<br />

dense foliage <strong>of</strong> a mistletoe plant.<br />

Traditionally used by forest harvesters,<br />

the term ‘stand’ refers to a small<br />

area with<strong>in</strong> a forest patch. The stand<br />

is a useful way to take a close up<br />

look at what is found with<strong>in</strong> a patch<br />

<strong>of</strong> brigalow woodland and how the<br />

animals that live <strong>in</strong> the woodland may<br />

see th<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

At this f<strong>in</strong>e scale, consider how many<br />

fallen logs are on the ground, how tall<br />

the trees are, how close together the<br />

trees are and how many shrubs you<br />

can see.<br />

From the animal’s perspective, a<br />

complex or messy woodland is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

WILL GOULDING<br />

a sign <strong>of</strong> good habitat. Fallen timber,<br />

stand<strong>in</strong>g dead trees, shrubs and a<br />

thick leaf litter are all signs <strong>of</strong> good<br />

homes for wildlife.<br />

Manag<strong>in</strong>g brigalow<br />

woodland stands<br />

for fauna:<br />

Good ground cover and a<br />

shrubby understorey can be<br />

achieved by m<strong>in</strong>imis<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

impact from graz<strong>in</strong>g animals –<br />

by exclud<strong>in</strong>g stock for periods<br />

<strong>of</strong> time to allow low plants to<br />

recover from brows<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

trampl<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Many animal homes can be<br />

provided by leav<strong>in</strong>g dead trees<br />

stand<strong>in</strong>g and allow<strong>in</strong>g dead<br />

timber to rot where it falls on the<br />

ground.<br />

Sometimes def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a patch is difficult;<br />

there may be no sharp boundary<br />

where it jo<strong>in</strong>s unmodified pasture. The<br />

size and shape <strong>of</strong> the entire woodland<br />

patch are important, as well as the<br />

distance between one woodland<br />

patch and another. For example, many<br />

animals need to move throughout a<br />

patch <strong>of</strong> woodland and perhaps to<br />

other patches <strong>of</strong> woodland to f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

food.<br />

Honeyeaters, like the striped<br />

honeyeater, will travel widely with<strong>in</strong> a<br />

day to f<strong>in</strong>d flower<strong>in</strong>g or fruit<strong>in</strong>g plants<br />

(such as mistletoes and eucalypt<br />

blossom). Less frequent but longer<br />

distance movements are necessary<br />

too. Seasonal visitors to the brigalow<br />

woodlands <strong>in</strong>clude the threatened<br />

pa<strong>in</strong>ted honeyeater that travels widely<br />

<strong>in</strong> New South Wales, Queensland and<br />

the Northern Territory and returns<br />

to the brigalow woodlands to breed<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the summer months.<br />

Other species like the metallic green<br />

Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoo and the<br />

raucous channel-billed cuckoo<br />

travel all the way from Papua New<br />

Gu<strong>in</strong>ea and Indonesia to the brigalow<br />

woodlands to breed dur<strong>in</strong>g summer.<br />

It’s not just migratory species that<br />

need to travel long distances. Many<br />

young animals need to leave their<br />

family home when they become<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent and they need to move<br />

considerable distances to f<strong>in</strong>d another<br />

suitable location that is unoccupied.<br />

12

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

These movements can be much more difficult <strong>in</strong> agricultural<br />

areas. Animals differ <strong>in</strong> their ability to travel across open<br />

country to f<strong>in</strong>d other woodland patches and are at greater<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> predation when cross<strong>in</strong>g open country. Some<br />

animals can only move with<strong>in</strong> woodland patches, so if the<br />

woodland patch they live <strong>in</strong> is too small, they will perish or<br />

be unable to breed.<br />

Manag<strong>in</strong>g brigalow woodland<br />

patches for wildlife:<br />

Leav<strong>in</strong>g large patches <strong>of</strong> woodland on your property<br />

will provide habitat for those species that cannot<br />

travel across open country.<br />

Leav<strong>in</strong>g trees and patches, or even clumps <strong>of</strong><br />

regrowth, <strong>in</strong> your paddocks will ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> connections<br />

between habitat patches by provid<strong>in</strong>g ‘stepp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

stones’ for the more mobile species.<br />

Connect<strong>in</strong>g your shade-l<strong>in</strong>es to one another will help<br />

animals that need to visit multiple brigalow woodland<br />

patches.<br />

Keep<strong>in</strong>g your shade-l<strong>in</strong>es as wide as possible, ideally<br />

> 100 m, will make it easier for animals to avoid the<br />

edges <strong>of</strong> woodland and farmland if they need to.<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

Tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the big picture:<br />

the landscape<br />

Animal populations need to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> connections with other<br />

populations <strong>in</strong> the landscape to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> genetic diversity<br />

and long-term persistence.<br />

In def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the term ‘landscape’, we need to th<strong>in</strong>k about<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual animals to decide what makes a landscape for<br />

them. In general, a landscape is def<strong>in</strong>ed as an area <strong>of</strong> land<br />

that is large compared to the scale <strong>of</strong> movement <strong>of</strong> the<br />

animal and <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong>cludes both suitable and less-suitable<br />

habitat.<br />

A landscape for a t<strong>in</strong>y burrow<strong>in</strong>g frog can be only a<br />

few hundred metres across, while for a honeyeater, the<br />

landscape might be kilometres across.<br />

In a practical sense, it is best to th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>of</strong> a landscape <strong>in</strong><br />

terms <strong>of</strong> the area <strong>of</strong> land that you manage, i.e., the entire<br />

property or multiple neighbour<strong>in</strong>g properties. At this<br />

landscape scale, it is important to th<strong>in</strong>k about the total<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> woodland compared to areas <strong>of</strong> production <strong>in</strong><br />

your area <strong>of</strong> management, and how well connected it is to<br />

other areas <strong>of</strong> woodland.<br />

This doesn’t necessarily mean a physical l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> trees –<br />

many animals can cross small gaps between patches – but<br />

if you are able to encourage woodland regeneration close<br />

to areas <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g woodland, this is better than creat<strong>in</strong>g an<br />

isolated patch.<br />

Most importantly, the more woodland cover you have <strong>in</strong><br />

your landscape, the better it is likely to be for wildlife. Every<br />

little bit counts.<br />

If you carefully th<strong>in</strong>k about how you manage the woodland<br />

stands, patches and entire landscape <strong>of</strong> your property then<br />

you are likely to achieve the best you can for a range <strong>of</strong><br />

animals.<br />

Manag<strong>in</strong>g your<br />

landscape for wildlife:<br />

Leav<strong>in</strong>g as much woodland <strong>in</strong> the landscape as<br />

possible will result <strong>in</strong> more wildlife.<br />

Protect woodland edges by avoid<strong>in</strong>g herbicide and<br />

pesticide spray drift <strong>in</strong>to woodland patches – this will<br />

help to avoid degradation and shr<strong>in</strong>kage <strong>of</strong> woodland<br />

patches.<br />

Good habitat quality at large scales can be achieved<br />

by work<strong>in</strong>g with neighbours to manage habitat on<br />

more than one property.<br />

13

How much vegetation?<br />

The ma<strong>in</strong> reason so many <strong>of</strong> our native animals have become rarer, and even threatened with ext<strong>in</strong>ction, is because<br />

we have removed much <strong>of</strong> their habitat. Less habitat means fewer <strong>in</strong>dividuals, lead<strong>in</strong>g to population decl<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

Smaller populations are at more risk <strong>of</strong> go<strong>in</strong>g ext<strong>in</strong>ct through chance events; <strong>in</strong> many regions, several species have<br />

disappeared altogether. So how much habitat do we need to reta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> our landscape if we want to keep most <strong>of</strong> our<br />

wildlife?<br />

The answer is complicated, because<br />

different species need different types<br />

and amounts <strong>of</strong> habitat. However,<br />

there are some general patterns that<br />

we can use as rules-<strong>of</strong>-thumb <strong>in</strong> the<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> detailed, species-specific<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

For example, research <strong>in</strong> southern<br />

Australian woodlands suggests that<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> bird species <strong>in</strong> the<br />

landscape decl<strong>in</strong>es most rapidly if<br />

vegetation cover drops below 10%.<br />

Yet work <strong>in</strong> the brigalow suggests<br />

that this threshold might be higher. In<br />

brigalow landscapes, more vegetation<br />

means more bird species at least up to<br />

30% vegetation cover.<br />

Our research has shown that there<br />

is no clear target for the amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> woodland necessary to support<br />

diverse reptile communities <strong>in</strong><br />

the brigalow. But we can say that<br />

landscapes with less than 20%<br />

native vegetation support much lower<br />

diversity and abundance <strong>of</strong> reptiles,<br />

particularly species that have limited<br />

ability to move across open country.<br />

Queensland Department <strong>of</strong> Environment and Resource Management<br />

As with birds, the more brigalow<br />

woodland <strong>in</strong> the landscape, the better<br />

the reptile community.<br />

This means that every effort to reta<strong>in</strong><br />

vegetation helps to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> the<br />

richness <strong>of</strong> wildlife communities – and<br />

this is especially true <strong>in</strong> landscapes<br />

with less than 30% <strong>of</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al<br />

vegetation rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. It also means<br />

that every small <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> vegetation<br />

cover, such as through retention <strong>of</strong><br />

regrowth vegetation, will help species<br />

return to the landscape. Actively<br />

encourag<strong>in</strong>g the regeneration <strong>of</strong><br />

brigalow regrowth <strong>in</strong> these landscapes<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> the best th<strong>in</strong>gs that can<br />

be done for wildlife, with the aim <strong>of</strong><br />

return<strong>in</strong>g overall woodland cover to at<br />

least 30% wherever possible.<br />

All native vegetation contributes to<br />

wildlife habitat – and <strong>in</strong> landscapes<br />

with less rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g habitat, every bit<br />

is crucial<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

14

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

<strong>Regrowth</strong> is important<br />

<strong>Regrowth</strong> represents a conservation barga<strong>in</strong> because regrowth can grow <strong>in</strong>to mature woodlands without the large<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>of</strong> time and resources associated with tree plant<strong>in</strong>g schemes. <strong>Brigalow</strong> has a remarkable capacity to<br />

regrow from root stock <strong>in</strong> the soil, sometimes even after a decade <strong>of</strong> cultivation.<br />

Long regarded as a nuisance by<br />

landholders, brigalow regrowth<br />

currently occupies large areas <strong>in</strong><br />

the <strong>Brigalow</strong> Belt. In comparison<br />

to tree plant<strong>in</strong>g, brigalow regrowth<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers a cost-effective and less<br />

labour-<strong>in</strong>tensive means for<br />

conduct<strong>in</strong>g broad-scale habitat<br />

restoration. This does not mean<br />

that restoration <strong>of</strong> habitat is without<br />

costs for the landholder – the<br />

choice to allow brigalow regrowth<br />

to regenerate could result <strong>in</strong> lost<br />

production. An <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g number<br />

<strong>of</strong> government-funded schemes<br />

provide compensation funds to<br />

landholders who restore former<br />

production lands.<br />

The structure and floristic<br />

composition <strong>of</strong> brigalow regrowth<br />

vegetation is <strong>of</strong>ten very different<br />

from the orig<strong>in</strong>al remnant<br />

woodlands.<br />

Above: The number <strong>of</strong> woodland dependent bird species occupy<strong>in</strong>g regrowth stands<br />

<strong>in</strong>creases with woodland age. After 30 years, regrowth can support as many bird<br />

species as remnant woodlands.<br />

After clear<strong>in</strong>g, young brigalow<br />

regrowth (≤15 years) is low,<br />

with no trees and few shrubs (apart from the brigalow<br />

itself). Intermediate age regrowth (16 – 30 years) exhibits<br />

characteristics overlapp<strong>in</strong>g both young and old regrowth,<br />

but is <strong>of</strong>ten more similar to old regrowth. Old regrowth (><br />

30 years) is taller, has fewer stems and a more ‘tree-like’<br />

shape than the younger shrubby regrowth. Fallen timber,<br />

hollows and a complex ground and shrub layer are still<br />

miss<strong>in</strong>g from old regrowth and may take more than 100<br />

years to develop. These differences <strong>in</strong> the characteristics <strong>of</strong><br />

regrowth woodland compared with remnant brigalow mean<br />

that regrowth does not provide identical habitat as the<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>al woodland.<br />

Over time, brigalow regrowth can develop <strong>in</strong>to important<br />

habitat. Few woodland birds are able to use brigalow<br />

regrowth <strong>in</strong> the first couple <strong>of</strong> decades <strong>of</strong> growth, but after<br />

30 years the regrowth can support the same number <strong>of</strong><br />

species that are found <strong>in</strong> mature woodlands.<br />

This does not mean that only old regrowth is valuable for<br />

fauna. Long before it can provide habitat for a diverse<br />

range <strong>of</strong> species, it can provide other benefits such as<br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g movement pathways for species that cannot<br />

cross paddocks and crops. The dense shrubby structure <strong>of</strong><br />

young regrowth is important breed<strong>in</strong>g habitat and shelter<br />

for animals hid<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>in</strong>troduced predators like cats and<br />

foxes. T<strong>in</strong>y birds like the superb and variegated fairy-wrens<br />

love to hide their nests <strong>in</strong> the young brigalow shrubs.<br />

Remnant<br />

CleareD<br />

Young regrowth<br />

(< 15 yrs)<br />

<strong>in</strong>termediate<br />

regrowth (15- 30 yrs)<br />

OLD regrowth<br />

(> 30 yrs)<br />

15

Manag<strong>in</strong>g dense <strong>Brigalow</strong> regrowth:<br />

To th<strong>in</strong> or not to th<strong>in</strong>?<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> regrowth is <strong>of</strong>ten very dense (sometimes > 15,000 stems per hectare) because <strong>of</strong> the plentiful root suckers<br />

produced follow<strong>in</strong>g clear<strong>in</strong>g. Very high densities are particularly common after multiple pull<strong>in</strong>g attempts on deep<br />

clay soils with gilgais.<br />

Stems compete <strong>in</strong>tensely with one<br />

another and grow slowly, so slowly<br />

that dense stands are <strong>of</strong>ten described<br />

as “stunted” or “locked up”. Given<br />

enough time, dense brigalow regrowth<br />

will almost certa<strong>in</strong>ly grow <strong>in</strong>to<br />

woodlands ak<strong>in</strong> to virg<strong>in</strong> stands, but is<br />

it possible to speed up the process by<br />

th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g manually? The answer is yes.<br />

An experimental th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g trial <strong>in</strong> dense<br />

27 year old regrowth near Millmerran<br />

showed that th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g to 4000 – 6000<br />

stems per hectare produces the best<br />

results for woodland recovery and<br />

wildlife habitat. More severe th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

will open up the canopy and allow<br />

grasses to establish. While this might<br />

seem a positive result for graz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

purposes, it is not so good for wildlife.<br />

High grass cover, particularly buffel<br />

grass, <strong>in</strong>creases the risk <strong>of</strong> fire (see<br />

pgs 10 & 19), which will slow down the<br />

restoration process by kill<strong>in</strong>g trees or<br />

promot<strong>in</strong>g even thicker regrowth.<br />

If the goal is to manage brigalow<br />

regrowth for wildlife habitat, then<br />

canopy cover should be ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed at<br />

more than 50% (i.e. on average more<br />

than half <strong>of</strong> the ground is shaded by<br />

tree canopy) <strong>in</strong> southern Queensland<br />

and northern New South Wales. In<br />

central and northern brigalow regions<br />

we recommend ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g tree cover<br />

at 70% because buffel grass grows<br />

more vigorously <strong>in</strong> these regions.<br />

In younger regrowth (e.g. 10–15 years<br />

old) it will be necessary to reta<strong>in</strong> more<br />

stems <strong>in</strong> order to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> adequate<br />

tree cover. In these cases it may be<br />

best to th<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> stages, for example th<strong>in</strong><br />

down to 10,000 stems per ha <strong>in</strong>itially,<br />

then a few years later th<strong>in</strong> down to<br />

6,000 stems per ha.<br />

If provid<strong>in</strong>g habitat for native fauna<br />

is not the primary goal <strong>of</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

regrowth, then the manager might<br />

want to encourage the growth <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced pasture grasses and<br />

manage fire risk by graz<strong>in</strong>g. It is<br />

16<br />

important to know that sites that are<br />

managed <strong>in</strong> this way will not support<br />

the same richness <strong>of</strong> fauna that they<br />

would if managed <strong>in</strong> the way we<br />

describe, as wildlife habitat. However,<br />

from a wildlife perspective, some trees<br />

are better than no trees at all, and so<br />

the more common fauna will even use<br />

regrowth areas which are managed for<br />

graz<strong>in</strong>g and stock shelter.<br />

Th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g methods<br />

Obviously r<strong>in</strong>gbark<strong>in</strong>g takes a lot <strong>of</strong><br />

time and effort, and there may be more<br />

efficient methods available. Regardless<br />

<strong>of</strong> the method used, secondary<br />

sucker<strong>in</strong>g will occur less if th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

done after good ra<strong>in</strong>. When th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g, it<br />

is important to reta<strong>in</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> stem<br />

sizes <strong>in</strong> a “natural” arrangement.<br />

For example, a completely random<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> stems yields very natural<br />

arrangements.<br />

Th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g for carbon<br />

Trees sequester carbon as they grow,<br />

but some species sequester more<br />

carbon than others. <strong>Brigalow</strong> is a<br />

high biomass species, mean<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

it stores a lot <strong>of</strong> carbon compared to<br />

other species from a similar climate.<br />

<strong>Brigalow</strong> regrowth therefore has<br />

considerable potential to be used<br />

as carbon s<strong>in</strong>ks. Although th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

releases some carbon (through the<br />

decay <strong>of</strong> treated stems), th<strong>in</strong>ned<br />

stands will recoup this carbon quickly<br />

and reach their carbon capacity sooner<br />

than unth<strong>in</strong>ned stands. Although<br />

slower, unth<strong>in</strong>ned stands are still likely<br />

to sequester carbon reasonably<br />

quickly.

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

roadside vegetation and tree-l<strong>in</strong>es:<br />

are they too narrow?<br />

Narrow l<strong>in</strong>ear strips <strong>of</strong> brigalow remnant woodland are a common feature <strong>in</strong> brigalow landscapes. Long narrow bands<br />

<strong>of</strong> woodland can extend for kilometres along the edges <strong>of</strong> roads, and shade-l<strong>in</strong>es mark the boundaries between<br />

paddocks, provid<strong>in</strong>g shade for stock and protect<strong>in</strong>g crops from w<strong>in</strong>d damage and heat stress.<br />

These narrow strips <strong>of</strong> vegetation are <strong>of</strong>ten thought to be<br />

unimportant for wildlife and <strong>of</strong>ten do not appear on maps <strong>of</strong><br />

protected remnant woodland because they are too narrow.<br />

However, our research has shown that these patches <strong>of</strong><br />

brigalow are <strong>of</strong> great importance to wildlife, support<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

wide variety <strong>of</strong> birds and reptiles.<br />

Many have a high abundance <strong>of</strong> mistletoe plants that<br />

provide important fruit and nectar food sources for<br />

woodland birds, like the rare pa<strong>in</strong>ted honeyeater. These<br />

woodlands also provide corridors for animals to move<br />

among patches <strong>of</strong> woodland.<br />

While wider patches generally provide better habitat<br />

for wildlife, even the very narrowest <strong>of</strong> patches are still<br />

important habitat. Very narrow (< 50 m wide) strips are<br />

particularly vulnerable to further degradation from spraydrift<br />

from adjacent cropp<strong>in</strong>g areas and over brows<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

trampl<strong>in</strong>g by cattle and sheep, as well as w<strong>in</strong>d and storm<br />

damage.<br />

The more heavily grazed <strong>of</strong> these narrow strips have few<br />

young trees regenerat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the understorey to replace<br />

mature trees as they die. The future <strong>of</strong> these woodlands is<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>, but there are ways to protect them from further<br />

damage.<br />

Exclud<strong>in</strong>g stock, or reduc<strong>in</strong>g the frequency <strong>of</strong> stock access,<br />

will help to ensure that younger trees can grow to maturity.<br />

Careful use <strong>of</strong> herbicides and reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g regrowth woodland<br />

on the edges <strong>of</strong> these patches are all ways to buffer these<br />

important habitat features aga<strong>in</strong>st further damage.<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

17

Key habitat features<br />

What are the most important features for fauna <strong>in</strong> a brigalow woodland stand?<br />

18<br />

High-quality <strong>Brigalow</strong> habitat<br />

complex habitat<br />

structure<br />

For most fauna, a tree canopy is<br />

not enough. In a patch <strong>of</strong> brigalow<br />

woodland, more complex habitat<br />

structure means more species will<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d a home. For example, small birds<br />

such as f<strong>in</strong>ches and fairy-wrens need<br />

dense vegetation, preferably sp<strong>in</strong>y<br />

shrubs, for protection from predators.<br />

Dense understorey also helps to keep<br />

aggressive noisy m<strong>in</strong>ers out.<br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g graz<strong>in</strong>g pressure with<strong>in</strong><br />

areas <strong>of</strong> brigalow woodland can<br />

preserve the important shrub layer and<br />

allow it to regenerate. Even areas <strong>of</strong><br />

young regrowth brigalow can act as<br />

shrubby habitat for small birds.<br />

WILL GOULDING<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

a messy ground layer<br />

A messy ground layer is a good ground<br />

layer. Terrestrial reptiles and small<br />

mammals need fallen timber and leaf<br />

litter for shelter, and this environment<br />

also favours the <strong>in</strong>vertebrates on which<br />

they feed. Melon holes hold water and<br />

create important microhabitats for<br />

frogs and reptiles which prefer damp<br />

areas.<br />

MICHIALA BOWEN<br />

Mistletoes<br />

Mistletoes are an <strong>of</strong>ten misunderstood<br />

component <strong>of</strong> Australian woodlands.<br />

There are many native species <strong>of</strong> these<br />

semi-parasitic plants <strong>in</strong> Australia and<br />

they provide important food (fruit and<br />

nectar), shelter and nest<strong>in</strong>g habitat for<br />

many types <strong>of</strong> animals. Their leaf litter<br />

also benefits ecosystems by return<strong>in</strong>g<br />

nutrients to the soil and enrich<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

ground layer.<br />

Grey mistletoes (Amyema quandang)<br />

are particularly abundant <strong>in</strong> narrow<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ear strips <strong>of</strong> remnant brigalow.<br />

Although many people worry that<br />

heavy mistletoe <strong>in</strong>festation will cause<br />

tree death, the science is less clear. We<br />

do know that their benefits generally<br />

out-weigh any negative effects. They<br />

are unlikely to harm healthy host<br />

trees and they are very important<br />

for ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the abundance and<br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> woodland birds that live <strong>in</strong>,<br />

or travel along, these remnant strips.<br />

Hollows and logs<br />

Hollows, cracks and crevices <strong>in</strong> trees<br />

and fallen logs are homes and havens<br />

for animals and plants <strong>in</strong> the brigalow.<br />

They provide places for animals to<br />

hide, breed, feed and bask. We <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

see lizards soak<strong>in</strong>g up the sun’s rays<br />

on a log, but many animals prefer to<br />

stay out <strong>of</strong> harm’s way <strong>in</strong> hollows and<br />

crevices: sleep<strong>in</strong>g, lay<strong>in</strong>g eggs, giv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

birth or car<strong>in</strong>g for young. Cracks and<br />

crevices <strong>in</strong> old and dead trees harbour<br />

native species that will be rendered<br />

homeless if needlessly removed.<br />

Logs on the ground help trap moisture<br />

and reduce erosion as well as act<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as a refuge for plants and animals.<br />

Bryophytes (collective term for<br />

mosses, hornworts and liverworts) are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten conspicuous on logs; the highest<br />

bryophyte abundance and diversity<br />

occur on old logs.<br />

Numerous species <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>vertebrate eat<br />

bryophytes, lay their eggs on them or<br />

shelter <strong>in</strong> them and this gives rise to a<br />

cha<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> higher order organisms that<br />

utilise this abundance <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>vertebrates.<br />

For example, many ants use older,<br />

decay<strong>in</strong>g logs and this attracts their<br />

predators such as native legless and<br />

burrow<strong>in</strong>g lizards.

CONSERVING BIODIVERSITY IN BRIGALOW LANDSCAPES<br />

Problem species<br />

ALEX McTAVISH<br />

Noisy m<strong>in</strong>er<br />

The noisy m<strong>in</strong>er (or mickey bird) is a native, but problematic<br />

species. Despite the name, it is not related to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced common (or Indian) myna, but to the Australian<br />

honeyeaters. Unlike most <strong>of</strong> our birds, it has benefited from<br />

the changes that humans have wrought <strong>in</strong> the landscape,<br />

and is more common now than prior to European<br />

settlement.<br />

Unfortunately, it is very aggressive towards other birds.<br />

Liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> large groups, noisy m<strong>in</strong>ers will chase and ‘mob’<br />

<strong>in</strong>truders to their territory. In almost all cases, smaller birds<br />

are chased away. Larger birds are attacked too, but are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten a bit more resilient.<br />

This means that a patch <strong>of</strong> woodland which is home to a<br />