The Challenges Of Testing For And Diagnosing Porphyrias

The Challenges Of Testing For And Diagnosing Porphyrias

The Challenges Of Testing For And Diagnosing Porphyrias

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Communiqué<br />

November 2002<br />

AVolume 27<br />

Number 11<br />

Features<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Challenges</strong> of <strong>Testing</strong><br />

<strong>For</strong> and <strong>Diagnosing</strong><br />

<strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

Inside<br />

Ask Us<br />

Abstracts of Interest<br />

Calendar<br />

Test Updates:<br />

• Cobalt Serum<br />

Specimen Correction<br />

• Metanephrine/<br />

Normetanephrine Test<br />

Adds Hypertensive<br />

Reference Range<br />

• Trichophyton Test Title<br />

Change<br />

W• Xanthine, Hypoxanthine,<br />

Purine, and Pyrimidine<br />

Move to LC-MS/MS<br />

New Test<br />

Announcements<br />

• Chlamydia trachomatis<br />

by Nucleic Acid<br />

Amplification<br />

• C trachomatis/N<br />

gonorrhoeae by Nucleic<br />

Acid Amplification<br />

• Hereditary Pancreatitis,<br />

Blood<br />

• Neisseria gonorrhoeae<br />

by Nucleic Acid<br />

Amplification<br />

• Postmortem Screening,<br />

Bile/Blood Spots<br />

• Testosterone, Total and<br />

Bioavailable, Serum<br />

Communiqué<br />

Stabile Building<br />

150 Third Street SW<br />

Rochester, Minnesota 55902<br />

1-800-533-1710<br />

communique@mayo.edu<br />

A M a y o R e f e r e n c e S e r v i c e s P u b l i c a t i o n<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Challenges</strong> of <strong>Testing</strong> <strong>For</strong> and<br />

<strong>Diagnosing</strong> <strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> porphyrias are a group of inborn errors of<br />

metabolism resulting from defects in the heme<br />

biosynthetic pathway. Enzymatic deficiencies<br />

resulting in the accumulation and excretion of<br />

intermediary metabolites cause characteristic<br />

clinical manifestations, which include<br />

neurological and psychological symptoms<br />

and/or cutaneous photosensitivity. Although<br />

these disorders have genetic causes,<br />

environmental factors may exacerbate symptoms,<br />

which significantly impacts the severity and<br />

course of disease. Early diagnosis coupled with<br />

education and counseling of the patient<br />

regarding the nature of the disease and<br />

avoidance of precipitating factors are important<br />

for successful management.<br />

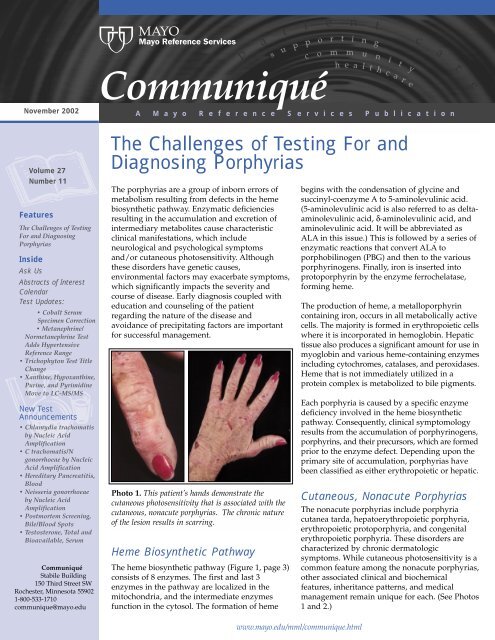

Photo 1. This patient’s hands demonstrate the<br />

cutaneous photosensitivity that is associated with the<br />

cutaneous, nonacute porphyrias. <strong>The</strong> chronic nature<br />

of the lesion results in scarring.<br />

Heme Biosynthetic Pathway<br />

<strong>The</strong> heme biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1, page 3)<br />

consists of 8 enzymes. <strong>The</strong> first and last 3<br />

enzymes in the pathway are localized in the<br />

mitochondria, and the intermediate enzymes<br />

function in the cytosol. <strong>The</strong> formation of heme<br />

begins with the condensation of glycine and<br />

succinyl-coenzyme A to 5-aminolevulinic acid.<br />

(5-aminolevulinic acid is also referred to as deltaaminolevulinic<br />

acid, δ-aminolevulinic acid, and<br />

aminolevulinic acid. It will be abbreviated as<br />

ALA in this issue.) This is followed by a series of<br />

enzymatic reactions that convert ALA to<br />

porphobilinogen (PBG) and then to the various<br />

porphyrinogens. Finally, iron is inserted into<br />

protoporphyrin by the enzyme ferrochelatase,<br />

forming heme.<br />

<strong>The</strong> production of heme, a metalloporphyrin<br />

containing iron, occurs in all metabolically active<br />

cells. <strong>The</strong> majority is formed in erythropoietic cells<br />

where it is incorporated in hemoglobin. Hepatic<br />

tissue also produces a significant amount for use in<br />

myoglobin and various heme-containing enzymes<br />

including cytochromes, catalases, and peroxidases.<br />

Heme that is not immediately utilized in a<br />

protein complex is metabolized to bile pigments.<br />

Each porphyria is caused by a specific enzyme<br />

deficiency involved in the heme biosynthetic<br />

pathway. Consequently, clinical symptomology<br />

results from the accumulation of porphyrinogens,<br />

porphyrins, and their precursors, which are formed<br />

prior to the enzyme defect. Depending upon the<br />

primary site of accumulation, porphyrias have<br />

been classified as either erythropoietic or hepatic.<br />

Cutaneous, Nonacute <strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> nonacute porphyrias include porphyria<br />

cutanea tarda, hepatoerythropoietic porphyria,<br />

erythropoietic protoporphyria, and congenital<br />

erythropoietic porphyria. <strong>The</strong>se disorders are<br />

characterized by chronic dermatologic<br />

symptoms. While cutaneous photosensitivity is a<br />

common feature among the nonacute porphyrias,<br />

other associated clinical and biochemical<br />

features, inheritance patterns, and medical<br />

management remain unique for each. (See Photos<br />

1 and 2.)<br />

www.mayo.edu/mml/communique.html

epidermis<br />

papillae<br />

vessels<br />

thickened basement<br />

membrane zone<br />

dermis<br />

Photo 2. This slide shows the thickened vessels, visible as<br />

bright-green donut shapes, and the thickened basement<br />

membrane zone that are characteristic of a diagnosis of<br />

porphyria.<br />

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda<br />

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is the most common<br />

porphyria and is most amenable to treatment. It is unique<br />

in that it may be an acquired (sporadic, type I) or an<br />

inherited (familial, types II and III) condition. About 75%<br />

of patients have type I PCT. In these cases, symptoms are<br />

precipitated by complications from liver diseases, such as<br />

hepatitis C and hereditary hemochromatosis, or by<br />

environmental exposures including certain medications,<br />

estrogens, alcohol abuse, iron overload, smoking, and<br />

occupational exposures to polychlorinated cyclic<br />

hydrocarbons. Historically, outbreaks have been caused<br />

by toxic exposure to certain organic chemicals.<br />

Observed less commonly is familial PCT. It is estimated<br />

that 25% of patients are affected with this autosomal<br />

dominant condition. In type II PCT, uroporphyrinogen<br />

decarboxylase activity is approximately 50% of normal<br />

in all tissues, while in type III the enzyme is deficient<br />

only in hepatic cells. In the absence of a positive family<br />

history, type III PCT is virtually indistinguishable from<br />

the sporadic form.<br />

PCT is characterized by photosensitivity and skin fragility.<br />

Patients experience blistering lesions in sun-exposed areas<br />

resulting in cutaneous thickening and scarring. <strong>The</strong> face,<br />

neck, forearms, and backs of hands are areas most often<br />

affected. Minor trauma may also trigger lesions. Twothirds<br />

of patients experience hypertrichosis (excessive hair<br />

growth) on the face, and less frequently on the ears and<br />

arms. Approximately half of individuals with PCT have<br />

hyperpigmentation in sun-exposed areas, while one-third<br />

of patients develop patches of alopecia as a result of<br />

scarring from large blisters on the scalp. In most cases,<br />

patients exhibit abnormal liver function tests. Long-term<br />

complications include an increased risk for hepatic<br />

cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Iron overload may<br />

occur in association with PCT. Hemosiderosis is usually<br />

mild or moderate, although can be severe. Interestingly,<br />

patients with hereditary hemochromatosis are more likely<br />

to experience symptoms of PCT than individuals in the<br />

general population.<br />

PCT is observed more frequently in males than in<br />

females. It is hypothesized that this may be related to<br />

varying levels of alcohol consumption and other<br />

environmental exposures between men and women. A<br />

second theory postulates that menses may provide a level<br />

of protection for women as it acts as a form of<br />

phlebotomy, which is an effective treatment for PCT.<br />

<strong>The</strong> diagnosis of PCT is easily established through<br />

elevations of uroporphyrin and heptacarboxylporphyrin<br />

in 24-hour urine porphyrins (#8562 Porphyrins,<br />

Quantitative, Urine) and uroporphyrin in plasma (#8733<br />

Porphyrins, Fractionation, Plasma). In PCT urine<br />

uroporphyrin levels are typically elevated to at least 4<br />

times the upper limit of normal, but concentrations may<br />

reach as high as 250 times the upper limit of normal. In<br />

general, heptacarboxylporphyrin is at least 25% of the<br />

uroporphyrin value. (Elevated uroporphyrin without a<br />

concomitant elevation of heptacarboxylporphyrin is often<br />

observed in the acute porphyrias, rather than PCT.)<br />

A urine uroporphyrin level twice the upper limit of<br />

normal is suspicious for PCT and justifies further<br />

investigation. Thus, subsequent plasma and fecal (#81652<br />

Porphyrins, Feces) porphyrin analyses and a repeat urine<br />

porphyrin analysis are recommended, particularly if<br />

symptoms develop or continue to persist. Plasma testing<br />

in cases of PCT demonstrates plasma porphyrin levels<br />

that are typically elevated at least 5 times the upper limit<br />

of normal. Conversely, mild elevations in plasma levels<br />

are associated with renal disease.<br />

Sporadic versus familial PCT can be distinguished by<br />

enzyme analysis (#8599 Uroporphyrinogen Decarboxylase<br />

[Upg D], Erythrocytes) and eliciting a thorough family<br />

history. Enzymatic assay is not an appropriate first-level<br />

assay as the majority of cases are sporadic and the enzyme<br />

exhibits normal activity in these cases.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cutaneous symptoms of PCT are more amenable to<br />

treatments than are similar complications seen in other<br />

forms of porphyria. Phlebotomy therapy and low-dose<br />

chloroquine, an antimalarial drug, result in complete<br />

2<br />

11/02

Figure 1. Heme Biosynthetic Pathway<br />

11/02 3

emission of skin lesions in most cases. Phlebotomy<br />

produces remission by gradually reducing the hepatic<br />

iron overload. Serial serum ferritin (#8689 Ferritin, Serum)<br />

and plasma porphyrin (#8733 Porphyrins, Fractionation,<br />

Plasma) levels are useful in evaluating the efficacy of<br />

treatment. Low-dose chloroquine treatments have proven<br />

valuable as the drug complexes with excess porphyrins,<br />

promoting excretion. However, these therapies should<br />

only be initiated following biochemical confirmation of<br />

the clinical diagnosis, as they are not useful in other<br />

porphyrias presenting with cutaneous symptoms.<br />

Occurrences of dermatologic complications can be<br />

minimized through elimination or reduction of<br />

precipitating factors via sun avoidance and use of<br />

sunscreen, abstaining from alcohol, discontinuing<br />

estrogen therapy, or treatment of an underlying liver<br />

disorder. Even with these treatments, long-term follow-up<br />

is important for all patients as a means of monitoring for<br />

relapse through urine (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative,<br />

Urine) and plasma (#8733 Porphyrins, Fractionation,<br />

Plasma) porphyrin analysis, and for the management of<br />

any concomitant liver disease.<br />

Generally, PCT is not attributable to a single causal factor.<br />

Even in familial PCT, most patients have identifiable risk<br />

factors in addition to the hereditary enzyme deficiency.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, all patients presenting with PCT should be<br />

evaluated for multiple risk factors, including testing for<br />

hepatitis C virus and screening for hemochromatosis, and<br />

treated accordingly.<br />

Hepatoerythropoietic Porphyria<br />

Hepatoerythropoietic porphyria (HEP) is a severe<br />

porphyria due to markedly deficient uroporphyrinogen<br />

decarboxylase activity or homozygous PCT. Onset of<br />

this rare porphyria usually occurs in infancy or<br />

childhood, although cases presenting in adulthood have<br />

been described. Patients experience severe<br />

photosensitivity leading to blistering lesions and<br />

scarring. Other complications include pink or red urine,<br />

hypertrichosis, erythrodontia (reddish discoloration of<br />

the teeth), hepatosplenomegaly, and hemolytic anemia.<br />

Treatment is limited to sun avoidance and the use of<br />

sunscreens.<br />

Erythropoietic Protoporphyria<br />

A deficiency of the enzyme ferrochelatase is observed in<br />

patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP). EPP<br />

is an autosomal dominant disorder with reduced<br />

penetrance. Only about 10% of individuals with an<br />

enzyme deficiency develop clinical symptoms. While<br />

onset usually occurs before 10 years of age, clinical<br />

presentation may occur during childhood or adulthood.<br />

Individuals with EPP are sensitive to most of the visible<br />

light spectrum. Such exposure causes burning, itching,<br />

and painful erythema and edema that can develop<br />

within minutes. Blistering and scarring is less common<br />

than in other dermatologic porphyrias. Repeated<br />

exposures may result in chronic changes giving the skin<br />

a waxy, thickened appearance with faint linear scars.<br />

Cutaneous photosensitivity is exacerbated in the spring<br />

and summer when exposure to sunlight is more likely.<br />

Patients are at an increased risk to develop hemolytic<br />

anemia. Gallstone formation is common, and some<br />

individuals with EPP experience mild hypertriglyceridemia.<br />

Liver dysfunction and hepatic failure are observed in up<br />

to 20% and less than 5% of patients, respectively.<br />

Patients with EPP accumulate protoporphyrin in<br />

erythrocytes, plasma, and feces. Other heme pathway<br />

intermediates do not accumulate, and protoporphyrin is<br />

not soluble in urine. <strong>For</strong> these reasons, urinary<br />

porphyrin, ALA, and PBG are not useful diagnostic tools<br />

for this disorder. When a diagnosis of EPP is suspected,<br />

the tests of choice are total porphyrins and<br />

protoporphyrin fractionation (#8536 Porphyrins, Total,<br />

Erythrocytes or #8739 Protoporphyrins, Fractionation,<br />

Erythrocytes) in erythrocytes. Unaffected individuals<br />

have approximately 60 µg/dL total protoporphyrin with<br />

approximately 85% being zinc-complexed and 15% or<br />

less free protoporphyrin. In EPP patients, the total<br />

erythrocyte protoporphyrin is significantly increased<br />

with values usually >200 µg/dL. Some patients have<br />

been observed with total protoporphyrin exceeding<br />

1000 µg/dL. When the total protoporphyrin is<br />

fractionated, EPP patients exhibit more free than zinccomplexed<br />

protoporphyrin. However, iron deficiency,<br />

lead intoxication, or in very rare cases variegate<br />

porphyria should be suspected in patients who exhibit<br />

total protoporphyrin in excess of 200 µg/dL but have<br />

more zinc-complexed than free protoporphyrin.<br />

Although EPP is the third most common porphyria,<br />

treatment options are limited. Sun avoidance is essential,<br />

and protective clothing and sunscreen are<br />

recommended. Oral administration of beta-carotene<br />

allows for increased tolerance to sunlight in most<br />

patients. Although there are no other known<br />

precipitating factors, many advocate the avoidance of<br />

drugs and other elements that may induce crises in the<br />

acute porphyrias. Liver transplantation is an option for<br />

4 11/02

the minority of patients who experience hepatic failure.<br />

However, this is not a cure as the excessive porphyrins<br />

are produced in the erythropoietic cells.<br />

Congenital Erythropoietic Porphyria<br />

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP), also known<br />

as Gunther disease, is an extremely rare and severe<br />

porphyria. It is an autosomal recessive condition<br />

resulting from markedly deficient uroporphyrinogen III<br />

cosynthase activity. Although the disorder typically<br />

manifests in early infancy, variability in the age of onset<br />

and severity are thought to be related to the level of<br />

residual enzyme activity. Prenatal manifestation of CEP<br />

presents as nonimmune hydrops fetalis (abnormal<br />

accumulation of serous fluid in fetal tissues) due to<br />

severe hemolytic anemia, whereas only cutaneous<br />

lesions are observed in the mildest cases manifesting in<br />

adulthood.<br />

Clinically, the majority of patients with CEP present in<br />

infancy with dermatological complications including<br />

photosensitivity, blistering, erythrodontia, and<br />

hypertrichosis. <strong>The</strong> skin may become thickened, and<br />

areas of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation are<br />

observed. Recurrent blistering and secondary infection<br />

may lead to significant scarring and mutilation.<br />

Exposure to sunlight and other sources of ultraviolet<br />

light exacerbate the severity of the cutaneous symptoms.<br />

In fact, some patients present at birth when undergoing<br />

phototherapy for hyperbilirubinemia. Ophthalmological<br />

findings include keratoconjunctivitis (inflammation of<br />

the conjunctiva and of the cornea), ulcerations, cataracts,<br />

and corneal scarring that can lead to blindness.<br />

Hemolytic anemia and other hematologic abnormalities<br />

accompanied by splenomegaly are common. To<br />

compensate for this, increased metabolic activity and<br />

expansion of the bone marrow may lead to pathologic<br />

fractures and vertebral compression or collapse. Many<br />

patients develop porphyrin-rich gallstones. Pink or<br />

reddish-brown urine is often observed as a result of the<br />

increased excretion of urinary porphyrins. Moreover,<br />

severely affected individuals exhibit growth and<br />

cognitive developmental delays and a decreased<br />

lifespan.<br />

A combination of urine (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative,<br />

Urine), erythrocyte (#8536 Porphyrins, Total, Erythrocytes<br />

and #8735 Porphyrins, Fractionation, Erythrocytes), and<br />

fecal (#81652 Porphyrins, Feces) porphyrin analyses can<br />

diagnose CEP. Porphyrins in urine are predominantly<br />

the I series isomers of uroporphyrin and<br />

coproporphyrin. Patients with CEP show elevated<br />

erythrocyte porphyrins consisting primarily of<br />

uroporphyrin I. Coproporphyrin I is detected in feces.<br />

<strong>The</strong> diagnosis of CEP should be confirmed by<br />

erythrocyte uroporphyrinogen III cosynthase enzyme<br />

analysis (#80288 Uroporphyrinogen III Synthase (Co-<br />

Synthase) (Upg III S), Erythrocytes). Enzyme analysis<br />

must be performed prior to blood transfusion to achieve<br />

the most accurate results. Furthermore,<br />

uroporphyrinogen III cosynthase testing is not useful<br />

for carrier testing, as CEP heterozygotes cannot be<br />

distinguished from unaffected individuals. Molecular<br />

studies are currently not available on a clinical basis, but<br />

may be obtained in a research setting.<br />

Treatment for CEP requires protection from ultraviolet<br />

light to reduce dermatological and ophthalmological<br />

complications. To minimize the risk of mutilation,<br />

secondary infections must be treated immediately.<br />

Blood transfusions and splenectomy are beneficial in<br />

some cases by decreasing porphyrin production and<br />

limiting hemolytic anemia. Allogenic bone marrow<br />

transplantation has proven curative for a handful of<br />

patients. However, this therapy carries a considerable<br />

risk for mortality.<br />

Acute <strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> acute porphyrias include acute intermittent<br />

porphyria, variegate porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria,<br />

and 5-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase<br />

deficiency. Episodic neurovisceral symptoms that can<br />

be life threatening characterize the acute porphyrias.<br />

Cutaneous features also may manifest in some patients.<br />

Acute episodes can be precipitated by both endogenous<br />

and exogenous factors. <strong>The</strong>se factors and clinical<br />

management are similar for all types of the acute<br />

porphyrias and are discussed following the clinical<br />

descriptions of each.<br />

Acute Intermittent Porphyria<br />

Acute intermittent porphyria (AIP), the second most<br />

common porphyria, results from a deficiency in the<br />

enzyme porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), also called<br />

uroporphyrinogen I synthase or hydroxymethylbilane<br />

synthase. AIP is aptly named for the intermittent<br />

episodes in which patients experience acute neuropathic<br />

symptoms. <strong>The</strong>se acute episodes are potentially lifethreatening,<br />

highly variable, and although usually short<br />

in duration, may last from a few days to several months.<br />

11/02 5

AIP rarely presents prior to puberty, with onset most<br />

commonly between ages 20 and 40. It is characterized<br />

by episodes of acute neuropathic symptoms. Most<br />

patients, approximately 95%, experience severe<br />

abdominal pain, often in conjunction with nausea,<br />

vomiting, and constipation. Peripheral neuropathy is<br />

common. However, given the extensive list of<br />

differential diagnoses for patients experiencing<br />

peripheral neuropathy, testing for AIP in the absence of<br />

abdominal pain rarely identifies AIP patients and is not<br />

recommended. Patients frequently display psychiatric<br />

symptoms presenting in the form of psychotic episodes,<br />

depression, and anxiety. Other features of an acute<br />

attack include circulatory disturbances such as<br />

hypertension and tachycardia. Dysuria and urinary<br />

retention, sometimes requiring catheterization, may be<br />

seen. Less frequently, patients may experience seizures,<br />

respiratory paralysis, fever, and diarrhea.<br />

Given the highly variable and nonspecific nature of the<br />

neurovisceral symptoms observed in AIP attacks, the<br />

condition is often overlooked in the clinical setting.<br />

Unfortunately, appropriate laboratory investigations are<br />

often not conducted, and many patients are misdiagnosed<br />

or become incorrectly labeled as narcotic seeking. This<br />

leads to a potentially life-threatening situation as<br />

patients continue to be at risk for an acute attack.<br />

Inheritance of AIP occurs in an autosomal dominant<br />

manner with reduced penetrance. Approximately<br />

10-20% of individuals with a PBGD enzyme deficiency<br />

will become symptomatic during their lifetime,<br />

although some recent studies have questioned this low<br />

penetrance rate. 1,2 While the vast majority of patients<br />

will never exhibit symptoms, the identification of<br />

asymptomatic, affected individuals in families with<br />

known AIP is crucial. <strong>The</strong> diagnosis of asymptomatic<br />

patients allows for the avoidance of precipitating<br />

factors, thereby minimizing the risk of a life-threatening<br />

porphyric attack.<br />

With respect to the initial diagnosis of symptomatic<br />

patients believed to be in an acute AIP crisis, urine<br />

porphyrins (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine),<br />

ALA (#8406 Aminolevulinic Acid [ALA], Urine), and<br />

PBG (#82068 Porphobilinogen, Quantitative, Random,<br />

Urine) should be analyzed. Substantial financial savings<br />

and improvement in the appropriateness of testing can<br />

be attained by following our suggested testing strategies<br />

for the acute porphyrias (see Table 1). 5 This will ensure<br />

that another acute porphyria, with features similar to<br />

AIP, is not missed. PBGD (#9625 Aminolevulinic Acid<br />

Dehydratase [ALA-D] and Porphobilinogen Deaminase<br />

[Pbg-D] (Uroporphyrinogen Synthase [UpgS]),<br />

Erythrocytes) enzyme activity should be evaluated<br />

either in conjunction with these urine analyses or<br />

preferably in a stepwise fashion when indicated, based<br />

upon the urine studies.<br />

Identification of asymptomatic, affected family<br />

members, including children, is possible and requires<br />

either biochemical or molecular analysis. However,<br />

molecular testing is not readily available on a clinical<br />

basis at this time. Urinary ALA and PBG values are<br />

method dependent and can vary by institution. Some<br />

experts believe that these analytes will never fall within<br />

the normal range in asymptomatic, affected individuals,<br />

whereas others argue that these values can normalize in<br />

such patients. With the assays available through Mayo<br />

Medical Laboratories (MML), elevated urinary ALA and<br />

PBG values have been observed in asymptomatic<br />

individuals in whom AIP status was previously unknown.<br />

Provision of clinical information and reason for referral<br />

is important for accurate result interpretation.<br />

Regarding the diagnosis of asymptomatic infants and<br />

children, there is evidence that PBGD activity fluctuates<br />

considerably during the first 9-12 months of life;<br />

therefore, enzyme analysis should be performed after 1<br />

year of age. In some cases, it is helpful to perform<br />

PBGD analysis of known affected family members<br />

when attempting to rule in/out AIP in asymptomatic<br />

relatives. Given that up to 10% of asymptomatic<br />

individuals with AIP will have a normal PBGD result,<br />

the urine assays are important diagnostic tools.<br />

Variegate Porphyria<br />

Variegate porphyria (VP) is an autosomal dominant<br />

acute porphyria that results from a reduction in the<br />

activity of protoporphyrinogen oxidase activity. VP is<br />

pan-ethnic, although high prevalence is reported in<br />

South Africa (3/1000 individuals) and Finland. Reduced<br />

penetrance is observed and symptoms very rarely<br />

present before puberty. Clinical presentation of VP is<br />

similar to other acute porphyrias, with symptoms<br />

including abdominal pain, vomiting, neuropathies, and<br />

psychiatric sequelae. However, cutaneous involvement<br />

is usually more pronounced. In fact, dermatologic<br />

manifestations in VP are very similar to those seen in<br />

PCT and include blistering, hyperpigmentation, and<br />

hypertrichosis of sun-exposed areas. Moreover, while<br />

neuropathic symptoms appear only during acute crisis,<br />

photosensitivity remains a chronic symptom.<br />

In rare instances, homozygous VP, with marked<br />

deficiency of protoporphyrinogen oxidase enzyme<br />

6<br />

11/02

activity, has been described. Patients typically present in<br />

early childhood with photosensitivity resulting in<br />

severe cutaneous manifestations, neurologic symptoms<br />

including seizures, and developmental delay.<br />

<strong>The</strong> diagnosis of VP relies upon porphyrin analysis in<br />

urine (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine) and feces<br />

(#81652 Porphyrins, Feces), as enzyme and molecular<br />

analysis of protoporphyrinogen oxidase are not readily<br />

available on a clinical basis. Depending upon whether<br />

the patient is experiencing an acute crisis or is<br />

asymptomatic, urine coproporphyrin, ALA, and PBG<br />

values are elevated to varying degrees. Values may be<br />

as high as 10-20 times normal during acute crises but<br />

may be normal or only mildly elevated between attacks.<br />

During crises, fecal porphyrin analysis shows<br />

coproporphyrin levels are, at a minimum, double with a<br />

coproporphyrin III to coproporphyrin I ratio in the 3-10<br />

range (normal ratio

attacks rarely occur before puberty, and attack frequency<br />

and severity decline after menopause. Interestingly, a<br />

subset of female patients experience regular, cyclical,<br />

exacerbations of disease in conjunction with menses.<br />

A variety of drugs, including alcohol, have been<br />

implicated in the induction of acute porphyric attacks.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is consensus regarding the use and safety of<br />

many common medications in patients with AIP. Other<br />

drugs are not as well understood. Some commonly used<br />

drugs, which have been classified as safe or unsafe for<br />

use by patients with an acute porphyria, are listed in<br />

Table 1. More extensive lists, including drugs whose<br />

safety is still in question, are available elsewhere. 3<br />

Medications previously established as safe should be<br />

used whenever possible in patients with asymptomatic<br />

or symptomatic AIP.<br />

Nutritional status, in particular decreased caloric intake,<br />

has been shown to induce the onset of an acute attack.<br />

Intercurrent illnesses and surgery exhibit a causal<br />

relationship, possibly due to increased energy requirements<br />

during these times. Additionally, psychological stress<br />

has been reported to contribute to AIP symptomology,<br />

though the underlying mechanisms are not understood.<br />

Precipitating factors likely act in an additive fashion,<br />

and the trigger(s) of a particular crisis, cannot always be<br />

ascertained.<br />

Table 1. Medications and the acute porphyrias<br />

Treatment for Acute <strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

Hospitalization is often necessary for the treatment of<br />

acute attacks. Crises are treated with increased<br />

carbohydrate intake that may occur via intravenous<br />

administration. Heme (hematin or heme arginate)<br />

therapy allows for the excretion of ALA and PBG.<br />

Efficacy is compromised if heme therapy is delayed, so<br />

treatment should commence as soon as possible after<br />

the onset of a crisis. Symptomatic treatment includes<br />

frequent doses of analgesics to control pain, and<br />

phenothiazines may be administered to control nausea,<br />

vomiting, and anxiety. Given that pain tends to be<br />

severe, narcotics are typically the analgesia of choice, as<br />

nonnarcotic agents are usually inadequate.<br />

Treatment for asymptomatic patients or between acute<br />

porphyria crises largely relies upon the prevention of<br />

potentially life-threatening episodes. At-risk individuals<br />

should be counseled to avoid medications known to<br />

precipitate attacks (Table 1), to avoid excessive alcohol<br />

intake, to seek prompt treatment for other intercurrent<br />

illnesses, and to maintain proper nutritional status,<br />

including the avoidance of crash dieting. Patients<br />

should be encouraged to wear a medical alert bracelet<br />

allowing for proper management in the event that the<br />

patient becomes temporarily incapacitated as a result of<br />

an accident or acute crisis. Photosensitivity can be<br />

minimized in VP and HCP patients by avoidance of sun<br />

exposure, protective clothing, and pharmacotherapy in<br />

the form of a beta-carotene analog, canthaxanthine.<br />

<strong>Testing</strong> for Porphyria<br />

By following our suggested testing strategy, the quality<br />

of patient care and cost-effectiveness of testing can be<br />

maximized. Depending upon the specific type of<br />

porphyria suspected, certain tests are more informative<br />

than other assays. In general, a 24-hour urine<br />

porphyrins (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine)<br />

analysis that includes porphobilinogen is the most<br />

effective screening tool. However, when EPP is the<br />

potential diagnosis, an erythrocyte porphyrin (#8536<br />

Porphyrins, Total, Erythrocytes and #8735 Porphyrins,<br />

Fractionation, Erythrocytes) and protoporphyrin<br />

fractionation (#8739 Protoporphyrins, Fractionation,<br />

Erythrocytes) are the most appropriate tests to perform.<br />

<strong>For</strong> a listing of informative biochemical findings for<br />

each type of porphyria, please refer to Table 2.<br />

<strong>Testing</strong> strategies for each suspected porphyria are<br />

outlined in Table 3, page 10. Ordering a battery of tests<br />

does not enhance the quality of patient care. Rather, a<br />

stepwise diagnostic approach is the most effective<br />

means of ruling in/out a specific porphyria. In most<br />

cases, when the result of the urine porphyrins test is<br />

normal, subsequent testing in the form of fecal, plasma,<br />

and erythrocyte porphyrin analyses and enzyme assay<br />

are not recommended. As shown, the 24-hour urine<br />

porphyrins (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine)<br />

analysis is the most appropriate starting point. If a<br />

8 11/02

Table 2. Informative Biochemical Findings in Porphyria<br />

particular diagnosis is suspected, additional first-line<br />

testing may be appropriate (tests listed in black in Table 3,<br />

page 10); other analyses (listed in red) may be delayed<br />

until initial results are available. While providing<br />

minimal clinical value, additional testing creates<br />

unnecessary expense to the referring laboratory or<br />

physician, health insurance company, and patient.<br />

<strong>For</strong> at least 1 week prior to testing for porphyria, and<br />

under the guidance of the physician, the use of<br />

medications should be avoided or minimized. If<br />

clinically inadvisable, or if the patient is in a crisis, a list<br />

of medications should accompany the specimen.<br />

Additionally, the patient should abstain from alcohol<br />

consumption for at least 24 hours prior to specimen<br />

collection.<br />

Abnormal results are reported with a detailed<br />

interpretation including an overview of the results and<br />

their significance, a correlation to available clinical<br />

information provided with the specimen, differential<br />

diagnosis, and recommendations for additional testing<br />

when indicated and available. <strong>For</strong> consultation<br />

regarding porphyrias, please contact a laboratory<br />

director or genetic counselor in the Biochemical<br />

Genetics Laboratory by calling Mayo Lab Inquiry<br />

(1-800-533-1710).<br />

Continues on page 10.<br />

References<br />

1. De Siervi A, Rossetti MV, Parera VE, Mendez M, Varela LS, del C<br />

Batlle AM. Acute intermittent porphyria: biochemical and clinical<br />

analysis in the Argentinean population. Clin Chim Acta 1999<br />

Oct;288(1-2):63-71<br />

2. <strong>And</strong>ersson C, Floderus Y, Wikberg A, Lithner F. <strong>The</strong> W198X and<br />

R173W mutations in the porphobilinogen deaminase gene in acute<br />

intermittent porphyria have higher clinical penetrance than R167W.<br />

A population-based study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2000<br />

Nov;60(7):643-83<br />

3. <strong>And</strong>erson KE, Sassa S, Bishop DF, Desnick RJ: Disorders of Heme<br />

Biosynthesis: X-Linked Sideroblastic Anemia and the <strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

(Chapter 124). In <strong>The</strong> Metabolic & Molecular Bases <strong>Of</strong> Inherited<br />

Disease, 8th edition. Edited by CR Scriver. New York, McGraw-Hill,<br />

2001, pp 2991-3062<br />

4. Matter, SET and Tefferi, A. Acute Porphyria: <strong>The</strong> Cost of Suspicion.<br />

Am J Med 1999 Dec;107:621-623<br />

11/02 9

Continued from page 9.<br />

Trichophyton Test Title Change<br />

<strong>The</strong> test name for #82720<br />

Trichophyton Mentagrophytes, IgE<br />

has been changed to #82720<br />

Trichophyton Rubrum, IgE to more<br />

accurately reflect the test being<br />

performed. This is a name change<br />

only.<br />

Cobalt Serum Specimen Correction<br />

In the October 2002 issue the new test<br />

announcement for #80084 Cobalt,<br />

Serum contained a typographical<br />

error in the specimen requirements.<br />

<strong>The</strong> correct specimen volume is 1.0 mL<br />

of serum in a Mayo metal-free,<br />

screw-capped, polypropylene vial.<br />

Table 3. Appropriateness of <strong>Testing</strong> for <strong>Porphyrias</strong><br />

Abstracts of Interest<br />

Application of Rapid-Cycle Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Detection of Microbial<br />

Pathogens: <strong>The</strong> Mayo-Roche Rapid Anthrax Test<br />

James R. Uhl, MS; Constance A. Bell, PhD; Lynne M. Sloan, MT(ASCP); Mark J. Espy, MS; Thomas F. Smith, PhD;<br />

Jon E. Rosenblatt, MD; <strong>And</strong> Franklin R. Cockerill III, MD<br />

Rapid-cycle real-time polymerase chain reaction has immediate and important implications for diagnostic<br />

testing in the clinical microbiology laboratory. In our experience this novel testing method has outstanding<br />

performance characteristics. <strong>The</strong> sensitivities for detecting microorganisms frequently exceed standard<br />

culture-based assays, and the time required to complete the assays is considerably shorter than that required<br />

for culture-based assays. We describe the principle of real-time polymerase chain reaction and present clinical<br />

applications, including the detection of Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax. This latter test is<br />

commercially available as the result of a collaborative venture between Mayo Clinic and Roche Applied<br />

Science, hence the designation <strong>The</strong> Mayo-Roche Rapid Anthrax Test.<br />

Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2002;77:673-680<br />

10 11/02

Metanephrine/Normetanephrine Test Adds<br />

Hypertensive Reference Range<br />

Hypertensives<br />

70 years: 148-560 µg/24 hour<br />

also may be asymptomatic or present with<br />

sustained, rather than episodic, hypertension or an<br />

incidentally discovered adrenal mass. Overall, most<br />

Hypertensives<br />

70 years: 246-753 µg/24 hour<br />

and pheochromocytoma patients.<br />

Hypertensives<br />

18 years: 44-261 µg/24 hour<br />

Hypertensives<br />

70 years: 180-646 µg/24 hour<br />

0-2 years: Not established<br />

Hypertensives<br />

3-8 years: 18-144 µg/24 hour<br />

18 years: 30-180 µg/24 hour<br />

Move to LC-MS/MS<br />

Hypertensives<br />

Recently, the Biochemical Genetics Laboratory<br />

70 years: 148-560 µg/24 hour<br />

82492<br />

11/02 11

Meeting Calendar<br />

Interactive Satellite Programs . . .<br />

October 22, 2002<br />

Bone Marker Assays: Are <strong>The</strong>y Useful for the Diagnosis<br />

& Treatment of Osteoporosis?<br />

Presenter: Lorraine Fitzpatrick, MD<br />

Moderator: Robert Kisabeth, MD<br />

November 19, 2002<br />

HIV Update<br />

Presenter: Zelalem Temesgen, MD<br />

Moderator: Robert Kisabeth, MD<br />

December 10, 2002<br />

Stroke Prevention and Management<br />

Presenter: David Wiebers, MD<br />

Moderator: Robert Kisabeth, MD<br />

<strong>For</strong> a complete listing of all the courses offered throughout the year,<br />

contact the Mayo Reference Services<br />

Education <strong>Of</strong>fice at 1-800-533-1710 or 507-284-8742.<br />

Did You Know?<br />

Childhood porphyrias are an uncommon group<br />

of metabolic disorders that result from inherited<br />

deficiencies of enzymes involved in the heme<br />

biosynthetic pathway. Although childhood<br />

porphyrias have been reported globally, their<br />

exact incidence is unknown. <strong>The</strong> inheritance<br />

patterns of these disorders are complex.<br />

Phenotypic variability is common among<br />

individual disease states and results partly from<br />

the presence of genetic heterogeneity. Childhood<br />

porphyrias typically present with<br />

photosensitivity and unique skin lesions. <strong>The</strong>rapy<br />

is limited and consists mostly of symptomatic<br />

and preventive measures. Although the disease<br />

course is variable, mortality from these disorders<br />

is rare.<br />

<strong>For</strong> the complete article, see “Childhood<br />

<strong>Porphyrias</strong>” by Iftikhar Ahmed MD, Mayo<br />

Clinic Proceedings 2002;77:825-836. <strong>The</strong><br />

complete article also is available on-line at<br />

www.mayo.edu/proceedings.<br />

Communiqué<br />

Editorial Board:<br />

Lee Aase<br />

Kathy Bates<br />

Jane C. Dale, MD<br />

Tammy Fletcher<br />

Terry Jopke<br />

Denise Masoner<br />

Anita Workman<br />

Communiqué Staff:<br />

Managing Editor: Denise Masoner<br />

Medical Editor: Jane C. Dale, MD<br />

Contributors: Iftikhar Ahmed MD; Franklin Cockerill III MD; Patricia Krause;<br />

Kara Mensink MS; April Studinski MS, CGC<br />

<strong>The</strong> Communiqué is published by Mayo Reference Services to provide laboratorians with<br />

information on new diagnostic tests, changes in procedures or normal values, and continuing<br />

medical education programs and workshops.<br />

A complimentary subscription of the Communiqué is provided to Mayo Medical Laboratories’<br />

clients.<br />

Stabile Building<br />

150 Third Street SW<br />

Rochester, Minnesota 55902-3332<br />

MC2831/R1102<br />

© 2002, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. MAYO, Mayo<br />

Reference Services and the triple-shield Mayo logo are trademarks and/or service marks of MFMER.

Q:<br />

A:<br />

Ask<br />

(<br />

US<br />

Why do you contact the ordering physician each time the coproporphyrin isomers test<br />

(#8652 Coproporphyrin Isomers, Series I & III, Urine) is ordered?<br />

<strong>The</strong> test for coproporphyrin isomers (#8652 Coproporphyrin Isomers, Series I & III, Urine) is often<br />

ordered incorrectly. This assay is primarily utilized to rule in/out the hyperbilirubinemia disorders,<br />

Dubin-Johnson or Rotor syndromes. It is not useful in the diagnosis of porphyrias. Bilirubin is derived<br />

exclusively from heme metabolism. In Dubin-Johnson and Rotor syndromes, conjugated bilirubin accumulates<br />

and transport is suppressed. Hyperbilirubinemia is the key feature of both syndromes. Patients with either<br />

disorder have normal liver function tests and histologically normal livers with the exception of gross<br />

pigmentation of the liver associated with Dubin-Johnson syndrome.<br />

When the coproporphyrin isomers (#8652) test is ordered, referring physicians are contacted via telephone to<br />

confirm the diagnosis in question as a means of ensuring the appropriate assay has been ordered. In most cases,<br />

the physician is concerned about a potential porphyria diagnosis, and the 24-hour urine porphyrins test (#8562<br />

Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine) is the appropriate test to order. <strong>The</strong> specimen requirements are identical,<br />

allowing for the coproporphyrin isomers to be canceled and the 24-hour urine porphyrins assay to be ordered.<br />

This thereby reduces expenses billed in turn to the referring laboratory or physician, health insurance company,<br />

and patient.<br />

As a referring laboratory, you can aid in minimizing the turnaround time and telephone calls to you and your<br />

referring physicians’ offices by confirming the suspected diagnosis prior to ordering testing or by providing<br />

clinical information with the specimen. If you have questions regarding this, please contact a genetic counselor in<br />

the Biochemical Genetics Laboratory by calling Mayo Laboratory Inquiry at 1-800-533-1710.<br />

Q:<br />

A:<br />

What is the most appropriate MML test to order when I want an analysis of uroporphyrins and<br />

coproporphyrins?<br />

In most instances, testing for uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin is requested to rule out porphyria.<br />

Urine porphyrin analysis (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine) provides quantitation of<br />

uroporphyrins, coproporphyrins, the intermediate porphyrins (pentacarboxyl, hexacarboxyl, and<br />

heptacarboxyl), and porphobilinogen. This test is generally the first step in evaluating a patient for porphyria.<br />

<strong>The</strong> interpretive result provided will guide the clinician in selecting additional testing as necessary.<br />

<strong>The</strong> analysis of coproporphyrin isomers (#8652 Coproporphyrin Isomers, Series I & III, Urine) is not a useful<br />

diagnostic tool for the porphyrias. This test should not be utilized when testing of uroporphyrins and<br />

coproporphyrins are desired.<br />

Continued on back<br />

11/02 Ask Us

Continued<br />

Q:<br />

A:<br />

If I suspect porphyria, what test should I order?<br />

When a porphyria diagnosis is suspected, it is most useful to begin the patient’s workup with a single<br />

test, the 24-hour quantitative urine porphyrin analysis (#8562 Porphyrins, Quantitative, Urine).<br />

Frequently, multiple porphyrin tests are inappropriately ordered on a patient. However, there is no need<br />

to begin an evaluation with this extensive level of testing. By beginning the assessment with testing for urine<br />

porphyrins and performing further testing only when indicated based upon these results, most porphyrias (see<br />

Q/A regarding EPP below), can be ruled out at minimal cost and inconvenience to the patient. When the urine<br />

porphyrin analysis yields abnormal results, the interpretive result provided will guide the clinician in selecting<br />

any appropriate additional tests.<br />

In cases where the results of the urine porphyrin analysis are normal, and the specimen was collected while the<br />

patient was experiencing symptoms (such as blistering or an acute crisis), further testing is generally not<br />

warranted. However, if the specimen was collected during an asymptomatic period, repeat testing should be<br />

considered when the patient is experiencing symptoms thought to be consistent with a porphyria.<br />

Q:<br />

A:<br />

What testing should be ordered when a diagnosis of erythropoietic protoporphyria is suspected?<br />

When erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is suspected, the appropriate tests of choice are total<br />

porphyrins and protoporphyrin fractionation (#8536 Porphyrins, Total, Erythrocytes or #8739<br />

Protoporphyrins, Fractionation, Erythrocytes) in erythrocytes. Unlike the evaluation of other porphyrias,<br />

analysis of urine porphyrins is not useful for this disorder because protoporphyrin is not soluble in urine and<br />

other heme pathway intermediates do not accumulate in the urine.<br />

Ask Us