magazine - Somerville College - University of Oxford

magazine - Somerville College - University of Oxford

magazine - Somerville College - University of Oxford

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Somerville</strong> Magzine | 19<br />

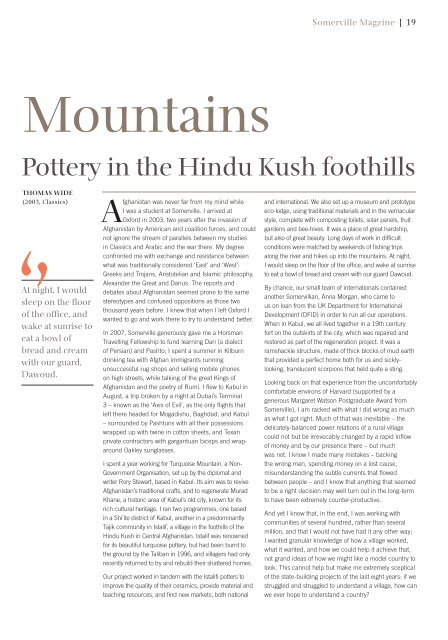

Mountains<br />

Pottery in the Hindu Kush foothills<br />

THOMAS WIDE<br />

(2003, Classics) Afghanistan was never far from my mind while<br />

I was a student at <strong>Somerville</strong>. I arrived at<br />

<strong>Oxford</strong> in 2003, two years after the invasion <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghanistan by American and coalition forces, and could<br />

not ignore the stream <strong>of</strong> parallels between my studies<br />

in Classics and Arabic and the war there. My degree<br />

confronted me with exchange and resistance between<br />

what was traditionally considered ‘East’ and ‘West’:<br />

Greeks and Trojans, Aristotelian and Islamic philosophy,<br />

At night, I would<br />

sleep on the floor<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fice, and<br />

wake at sunrise to<br />

eat a bowl <strong>of</strong><br />

bread and cream<br />

with our guard,<br />

Dawoud.<br />

Alexander the Great and Darius. The reports and<br />

debates about Afghanistan seemed prone to the same<br />

stereotypes and confused oppositions as those two<br />

thousand years before. I knew that when I left <strong>Oxford</strong> I<br />

wanted to go and work there to try to understand better.<br />

In 2007, <strong>Somerville</strong> generously gave me a Horsman<br />

Travelling Fellowship to fund learning Dari (a dialect<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persian) and Pashto; I spent a summer in Kilburn<br />

drinking tea with Afghan immigrants running<br />

unsuccessful rug shops and selling mobile phones<br />

on high streets, while talking <strong>of</strong> the great Kings <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghanistan and the poetry <strong>of</strong> Rumi. I fl ew to Kabul in<br />

August, a trip broken by a night at Dubai’s Terminal<br />

3 – known as the ‘Axis <strong>of</strong> Evil’, as the only fl ights that<br />

left there headed for Mogadishu, Baghdad, and Kabul<br />

– surrounded by Pashtuns with all their possessions<br />

wrapped up with twine in cotton sheets, and Texan<br />

private contractors with gargantuan biceps and wraparound<br />

Oakley sunglasses.<br />

I spent a year working for Turquoise Mountain, a Non-<br />

Government Organisation, set up by the diplomat and<br />

writer Rory Stewart, based in Kabul. Its aim was to revive<br />

Afghanistan’s traditional crafts, and to regenerate Murad<br />

Khane, a historic area <strong>of</strong> Kabul’s old city, known for its<br />

rich cultural heritage. I ran two programmes, one based<br />

in a Shi’ite district <strong>of</strong> Kabul, another in a predominantly<br />

Tajik community in Istalif, a village in the foothills <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Hindu Kush in Central Afghanistan. Istalif was renowned<br />

for its beautiful turquoise pottery, but had been burnt to<br />

the ground by the Taliban in 1996, and villagers had only<br />

recently returned to try and rebuild their shattered homes.<br />

Our project worked in tandem with the Istalifi potters to<br />

improve the quality <strong>of</strong> their ceramics, provide material and<br />

teaching resources, and find new markets, both national<br />

and international. We also set up a museum and prototype<br />

eco-lodge, using traditional materials and in the vernacular<br />

style, complete with composting toilets, solar panels, fruit<br />

gardens and bee-hives. It was a place <strong>of</strong> great hardship,<br />

but also <strong>of</strong> great beauty. Long days <strong>of</strong> work in difficult<br />

conditions were matched by weekends <strong>of</strong> fishing trips<br />

along the river and hikes up into the mountains. At night,<br />

I would sleep on the floor <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fice, and wake at sunrise<br />

to eat a bowl <strong>of</strong> bread and cream with our guard Dawoud.<br />

By chance, our small team <strong>of</strong> internationals contained<br />

another Somervillian, Anna Morgan, who came to<br />

us on loan from the UK Department for International<br />

Development (DFID) in order to run all our operations.<br />

When in Kabul, we all lived together in a 19th century<br />

fort on the outskirts <strong>of</strong> the city, which was repaired and<br />

restored as part <strong>of</strong> the regeneration project. It was a<br />

ramshackle structure, made <strong>of</strong> thick blocks <strong>of</strong> mud earth<br />

that provided a perfect home both for us and sicklylooking,<br />

translucent scorpions that held quite a sting.<br />

Looking back on that experience from the uncomfortably<br />

comfortable environs <strong>of</strong> Harvard (supported by a<br />

generous Margaret Watson Postgraduate Award from<br />

<strong>Somerville</strong>), I am racked with what I did wrong as much<br />

as what I got right. Much <strong>of</strong> that was inevitable – the<br />

delicately-balanced power relations <strong>of</strong> a rural village<br />

could not but be irrevocably changed by a rapid infl ow<br />

<strong>of</strong> money and by our presence there – but much<br />

was not. I know I made many mistakes – backing<br />

the wrong man, spending money on a lost cause,<br />

misunderstanding the subtle currents that fl owed<br />

between people – and I know that anything that seemed<br />

to be a right decision may well turn out in the long-term<br />

to have been extremely counter-productive.<br />

And yet I know that, in the end, I was working with<br />

communities <strong>of</strong> several hundred, rather than several<br />

million, and that I would not have had it any other way;<br />

I wanted granular knowledge <strong>of</strong> how a village worked,<br />

what it wanted, and how we could help it achieve that,<br />

not grand ideas <strong>of</strong> how we might like a model country to<br />

look. This cannot help but make me extremely sceptical<br />

<strong>of</strong> the state-building projects <strong>of</strong> the last eight years: if we<br />

struggled and struggled to understand a village, how can<br />

we ever hope to understand a country?