Fall & Winter 2012: Volume 33, Numbers 3 & 4 - Missouri Prairie ...

Fall & Winter 2012: Volume 33, Numbers 3 & 4 - Missouri Prairie ...

Fall & Winter 2012: Volume 33, Numbers 3 & 4 - Missouri Prairie ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Fall</strong>/winter<br />

<strong>2012</strong><br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>33</strong><br />

<strong>Numbers</strong> 3 & 4<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal<br />

The <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation<br />

Protecting Native Grasslands<br />

MPF <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

Protection<br />

and Outreach<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong>-chicken<br />

Translocation<br />

30 Years for<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park

Message from the President<br />

To make a<br />

prairie it takes<br />

a clover and<br />

one bee,<br />

One clover,<br />

and a bee,<br />

And revery.<br />

The revery<br />

alone will do,<br />

If bees are few.<br />

Emily Dickinson, 1896<br />

Don Kurz<br />

People are fond of saying that life is becoming<br />

more and more complex. Perhaps.<br />

But in a fundamental sense life is getting<br />

simpler. And that is not a good thing. Biological<br />

systems are shedding complexity (diversity) at<br />

an alarming rate. As individuals it is perplexing<br />

to know what to do. I am encouraged when I<br />

encounter a book like Doug Tallamy’s, Bringing<br />

Nature Home, and was delighted to be among<br />

the 300 people who came to hear him speak in<br />

Jefferson City on August 30. His book is being<br />

recommended to you by many. I simply want to<br />

join the chorus.<br />

As MPF members, you are slowing the loss<br />

of biological diversity through your support of<br />

MPF’s prairie protection efforts. MPF’s remnant<br />

prairies—and our prairie reconstructions—harbor<br />

incredible species richness. At home, you can also<br />

do much to help a diversity of native life forms<br />

by landscaping with natives. Native plants are<br />

palatable to native insects (which are largely specialists),<br />

and native insects create food for native<br />

birds and small mammals. One trophic level<br />

underpins the next. Give it a try. Grow Native!<br />

This is my last letter to you as president of<br />

MPF. This organization will select a new slate of<br />

officers at the annual meeting on October 13. I<br />

would like to take this opportunity to thank each<br />

board member, Carol, Richard, and you for your<br />

involvement in the important task of protecting<br />

prairies in <strong>Missouri</strong>. For me it is a privilege to be<br />

part of the effort. I’ll see you on the prairie.<br />

Stan Parrish, President<br />

Stan may have finished his term as president, but you’ll<br />

still find him hard at work on MPF prairies.<br />

Brian Edmond<br />

The mission of the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation (MPF)<br />

is to protect and restore prairie and other<br />

native grassland communities through<br />

acquisition, management, education, and research.<br />

Board roster as of September 21, <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

Officers<br />

President Stanley M. Parrish, Walnut Grove, MO<br />

Vice President Doris Sherrick, Peculiar, MO<br />

Secretary Bruce Schuette, Troy, MO<br />

Treasurer Laura Church, Kansas City, MO<br />

Directors<br />

Glenn Chambers, Columbia, MO<br />

Page Hereford, St. Louis, MO<br />

Wayne Morton, M.D., Osceola, MO<br />

Steve Mowry, Trimble, MO<br />

Rudi Roeslein, St. Louis, MO<br />

Jan Sassmann, Bland, MO<br />

Mike Skinner, Republic, MO<br />

Bonnie Teel, Rich Hill, MO<br />

Jon Wingo, Florrisant, MO<br />

Van Wiskur, Pleasant Hill, MO<br />

Vacancy<br />

Vacancy<br />

Presidential Appointees<br />

Dale Blevins, Independence, MO<br />

Margo Farnsworth, Smithville, MO<br />

Galen Hasler, M.D., Madison, WI<br />

Scott Lenharth, Nevada, MO<br />

Emeritus<br />

Bill Crawford, Columbia, MO<br />

Bill Davit, Washington, MO<br />

Clair Kucera, Columbia, MO<br />

Lowell Pugh, Golden City, MO<br />

Owen Sexton, St. Louis, MO<br />

Technical Advisors<br />

Max Alleger, Clinton, MO<br />

Jeff Cantrell, Neosho, MO<br />

Steve Clubine, Windsor, MO<br />

Dennis Figg, Jefferson City, MO<br />

Mike Leahy, Jefferson City, MO<br />

Rick Thom, Jefferson City, MO<br />

James Trager, Pacific, MO<br />

Staff<br />

Richard Datema, <strong>Prairie</strong> Operations Manager, Springfield, MO<br />

Carol Davit, Executive Director and <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Editor,<br />

Jefferson City, MO<br />

2 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4

Contents<br />

<strong>Fall</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong><br />

<strong>2012</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> <strong>33</strong>, <strong>Numbers</strong> 3 & 4<br />

Editor: Carol Davit,<br />

1311 Moreland Ave.<br />

Jefferson City, MO 65101<br />

phone: 573-356-7828<br />

info@moprairie.com<br />

Designer: Tracy Ritter<br />

Technical Review: Mike Leahy,<br />

Bruce Schuette<br />

Proofing: Doris and Bob Sherrick,<br />

Bill and Joyce Davit<br />

The <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal<br />

is mailed to <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

Foundation members as a benefit<br />

of membership. Please contact the<br />

editor if you have questions about<br />

or ideas for content.<br />

12<br />

4<br />

Regular membership dues to<br />

MPF are $35 a year. To become a<br />

member, to renew, or to give a<br />

free gift membership when you<br />

renew, send a check to<br />

18<br />

22<br />

2 Message from the President<br />

4 MPF Protection, Education, and Outreach Update<br />

By Carol Davit<br />

12 Five Years of Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Translocation<br />

By Max Alleger<br />

16 A Big Thank You to Smoky Hills Landowners<br />

By Steve Clubine<br />

18 30th Anniversary for <strong>Prairie</strong> State Park<br />

By Brian Miller<br />

22 Grow Native!<br />

Achieving Balance with Native Landscaping<br />

By Cindy Gilberg<br />

24 Jeff Cantrell’s Education on the <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

25 Steve Clubine’s Native Warm-Season Grass News<br />

29 <strong>Prairie</strong> Postings<br />

Back cover Calendar of Events<br />

membership address:<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation<br />

c/o Martinsburg Bank<br />

P.O. Box 856<br />

Mexico, MO 65265-0856<br />

or become a member on-line at<br />

www.moprairie.org<br />

General e-mail address<br />

info@moprairie.com<br />

Toll-free number<br />

1-888-843-6739<br />

www.moprairie.org<br />

Questions about your membership<br />

or donation? Contact Jane<br />

Schaefer, who administers<br />

MPF’s membership database at<br />

janeschaefer@earthlink.net.<br />

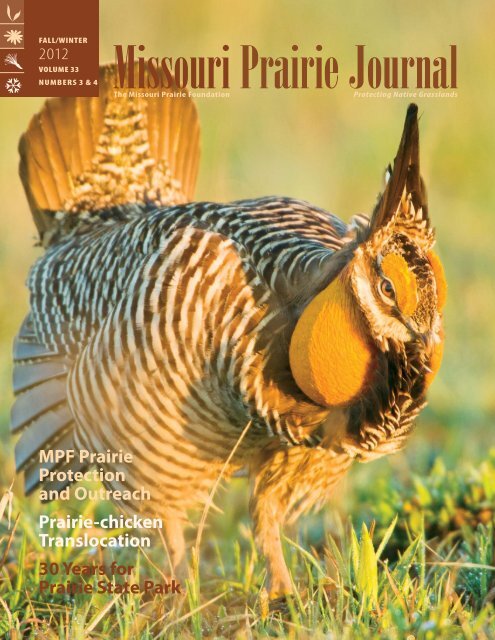

On the cover:<br />

Noppadol Paothong<br />

took the photo of this<br />

booming male greater<br />

prairie-chicken on<br />

MPF’s Golden <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

a decade ago. The Mo.<br />

Dept. of Conservation’s<br />

translocation effort aims<br />

to increase populations<br />

of this grassland bird<br />

(see page 12). Join fellow<br />

prairie enthusiasts on<br />

Oct. 27 to learn about<br />

the making of Save the<br />

Last Dance, Noppadol’s<br />

and Joel Vance’s new<br />

book on grassland<br />

grouse (see back cover).<br />

#8426<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 3

update<br />

MPF p r a i r i e protection, education, and outreach<br />

From left, MPF President<br />

Stan Parrish stands<br />

with Carol Davit, executive<br />

director of MPF,<br />

and Tim Ripperger,<br />

assistant director of the<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> Department<br />

of Conservation, at the<br />

Grow Native! ceremony<br />

“transplanting” the<br />

ten-year old native<br />

landscaping marketing<br />

and education program<br />

from the Department of<br />

Conservation to MPF. The<br />

ceremony was held after<br />

the lecture by Bringing<br />

Nature Home author<br />

Dr. Douglas Tallamy,<br />

organized by Lincoln<br />

University’s Native Plant<br />

Program in Jefferson<br />

City. MPF was one of the<br />

sponsors of the event.<br />

Read more on page 8.<br />

Robert Weaver<br />

Taking a Stand for <strong>Prairie</strong> and Native Plants<br />

The <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation (MPF) protects some of the most biologically diverse<br />

and beautiful prairies in the state. We do this through ongoing management, and we<br />

also take on major prairie restoration and reconstruction projects—such as our current<br />

work at our Welsch Tract. We also encourage others to plant prairie species and assist<br />

them with outreach activities like our recent <strong>Prairie</strong> Planting from Seed Workshop.<br />

As the new home of the Grow Native! native landscaping marketing and education<br />

program, MPF is expanding its conservation reach to home gardeners, landscape<br />

professionals, and many others who want to make yards, corporate campuses, farms,<br />

land owned by local governments, and school grounds more biologically diverse.<br />

MPF is a leader in taking a stand for prairie. We advocate for robust conservation<br />

programs in the Farm Bill and for secure funding for the federal State and Tribal Wildlife Grant<br />

program. MPF works with partners including the <strong>Missouri</strong> Bird Conservation Initiative, <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

Department of Conservation, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on initiatives ranging from<br />

native plants as a biofuel source to landscape-scale conservation planning—we all work together<br />

to broadcast the very important conservation message. By ensuring that the “prairie and<br />

native plant voice” has a seat at the table, MPF contributes to statewide, regional, and national<br />

conservation-friendly policies.<br />

Through other outreach and educational activities—such as our third annual <strong>Prairie</strong> BioBlitz<br />

held last June—MPF provides adults and children with in-depth nature exploration and one-onone<br />

learning with specialists of many prairie species. I think everyone with MPF is moved and<br />

inspired by the passion and hard work of MPF members and other supporters who volunteer<br />

during cold winter prairie workdays and by those who donate their time, money, energy, and<br />

talents to organize events like last June’s <strong>Prairie</strong> Paint Out (see page 6).<br />

MPF has accomplished much this year. In addition to our prairie protection work and outreach<br />

activities, the organization is continually improving its structure and governance. The Land<br />

Trust Alliance Organizational Assessment we undertook this year is prioritizing tasks for board<br />

members and staff to continue to move forward. As always, MPF remains lean—we have no office,<br />

no debt, only two staff members who work out of their homes or in the field, the board adopts<br />

only balanced budgets, and we conduct an independent annual audit. Your contributions to<br />

MPF are carefully managed to maximize your investment in conservation. Thank you for your<br />

continued support! MPF and its work to protect prairies could not exist without you.<br />

—Carol Davit, executive director<br />

bob ball<br />

MPF at Butterfly Festival in Springfield<br />

The Fourth Annual Friends of the Garden Butterfly Festival was held at<br />

Springfield’s Nathanael Greene/Close Memorial Park on July 21. MPF was<br />

there, along with 2,000 total visitors! Several people visiting the MPF booth<br />

expressed interest in learning how to establish native plantings on their property.<br />

One attendee came specifically to see the progress on the Kickapoo Edge<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Garden within the park, the restoration of which is overseen by several<br />

MPF members. Thanks go to MPF members and volunteers Ric and Jean Mayer<br />

who organized everyone and set up the booth, Stan and Susan Parrish who took<br />

it down, and Jeff Cantrell, Will Hardiman, and Jim Maggard who helped in<br />

between.<br />

Many thanks also to Stan and Susan Parrish who spent May 19 at an event<br />

for children in the park called Young Sprouts In The Garden. Stan and Susan<br />

demonstrated the power of prairie roots! Many thanks to Jeff Cantrell, Pat<br />

Mann, and Jean Mayer for creative support and Merv Wallace who donated the<br />

real roots from compass plant and little bluestem.<br />

4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4

MPF’s Third Annual <strong>Prairie</strong> BioBlitz<br />

Sara Scheill<br />

Fisheries Biologist Tom Priesendorf and the aquatic group examine<br />

fish from a stream on the prairie; below left, biologist Emily Imhoff<br />

shows off a grassland crayfish; below right, insect enthusiasts<br />

examine a beetle found by Dr. James Trager.<br />

Carol Davit<br />

Mervin Wallace Carol Davit<br />

MPF’s Third Annual <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

BioBlitz was held June 9 and<br />

10 at beautiful Schwartz<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong>. More than 100 participants<br />

explored the prairie,<br />

documented plants and animals,<br />

enjoyed a huge, fantastic potluck<br />

dinner with jambalaya cooked<br />

on-site, were treated to evening<br />

astronomical interpretation<br />

by members of the Kansas<br />

City Astronomical Society, and<br />

camped on the prairie. The plant<br />

and animal species tally included<br />

11 ants; 23 butterflies and<br />

moths; five native bees; 40 other<br />

insects, ranging from beetles to<br />

crickets to true bugs and more;<br />

16 amphibians and reptiles; 34<br />

birds; six fish, including several<br />

headwater stream species; <strong>33</strong><br />

mosses, liverworts, and hornworts,<br />

and 21 additional native<br />

vascular plant species, bringing<br />

the known total to date to 361<br />

native vascular plants. Many<br />

thanks to all the BioBlitz leaders<br />

for their time and expertise!<br />

Clockwise from top, dickcissel nest found by the bird group; Jessie gets a visit<br />

from a hairstreak butterfly; Nels Holmberg, far right, and members of the<br />

bryophyte group examine mosses; children and adults enjoying the prairie;<br />

lepidopterans search for butterflies; night owls observe and document noctural<br />

insects at a black light; and Dana Ripper and Ethan Duke of the Mo. River<br />

Bird Observatory set up a mist nest with helpers.<br />

Sara Scheill<br />

Carol Davit<br />

Brian Edmond<br />

Brian Edmond<br />

Save the Dates! MPF’s Fourth Annual <strong>Prairie</strong> BioBlitz will be held June 1 and 2, 2013<br />

at Denison and Lattner <strong>Prairie</strong>s in Barton and Vernon Counties.<br />

Brian Edmond<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 5<br />

Brian Edmond

MPF p r a i r i e protection, education, and outreach<br />

Ready to cut the ribbon on<br />

the farm’s new prairie garden<br />

are, above from left, Deborah<br />

Casolari, Chair, Board of<br />

Trustees, Jones-Seelinger-<br />

Johannes Family Foundation<br />

(Poplar Heights Farm), Brian<br />

Phillips, the farm’s executive<br />

director, MPF Board Member<br />

Dale Blevins, and MPF’s Vice<br />

President Doris Sherrick.<br />

Above right, MPF board<br />

member Dale Blevins next to<br />

the prairie garden. “It was<br />

a beautiful day for tasting<br />

heirloom veggies, sauces,<br />

melons, and drinks” said Dale.<br />

“After the tasting event, we<br />

were given an ATV tour of the<br />

farm and the site of future<br />

prairie gardens.”<br />

6 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4<br />

Poplar Heights Farm<br />

Poplar Heights Farm<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Garden Ribbon Cutting<br />

On September 8, Poplar Heights Farm in Bates County held a<br />

ribbon-cutting ceremony to officially open the farm’s prairie and<br />

other gardens during its Heirloom Tomato Festival. The farm<br />

was the recipient of MPF’s first <strong>Prairie</strong> Gardens Grant in <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

Poplar Heights Farm is an 1890s-era living history farm of<br />

640 acres. Part is farmed, with heirloom vegetables in visitorfriendly<br />

gardens. The farm also has an unplowed prairie remnant<br />

of about 20 acres and uses prescribed fire to help maintain it.<br />

The farm wanted to create prairie gardens to highlight the prairie<br />

heritage of the area. “I was impressed by the prairie garden and<br />

the signage,” said Dale. “The folks who run Poplar Heights Farm<br />

are very enthused about their living history farm and the prairie<br />

gardens.”<br />

Congratulations, Poplar Heights Farm! MPF’s <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

Gardens Small Grants program is made possible by a permanent<br />

fund established in 2011 thanks to generous contributions from<br />

MPF supporters. See page 31 for details on the 2013 grant.<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Planting with<br />

Seed Workshop<br />

Sixty members and other prairie<br />

enthusiasts registered for MPF’s <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

Planting from Seed Workshop, held<br />

September 8 at <strong>Prairie</strong> Star Restoration<br />

Farm. MPF board member Jon Wingo,<br />

president of DJM Ecological Services,<br />

and MPF member Frank Oberle,<br />

of Pure Air Native Seed, donated<br />

their time to give the workshop<br />

presentations, covering many aspects of<br />

establishing prairie plantings from seed, from eradication of tall fescue and other undesirable<br />

vegetation to seeding methods and on-going maintenance.<br />

MPF board member Jan Sassmann and her husband Bruce hosted the event at their<br />

restored 1926 barn and property featuring prairie plantings and restored woodlands. Jan<br />

even prepared lunch—including homemade soups—for the crowd. Bruce and Jan provided<br />

tours of their property following the morning presentations and lunch. Seth Barrioz, private<br />

land conservationist with the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation, also provided cost-share<br />

information and management advice. Thank you Jan, Bruce, Jon, Frank, and Seth!<br />

Frank Oberle<br />

Marla Blevins<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Paint Out at<br />

Bethany Springs<br />

Farm Nearly 400 prairie<br />

and art lovers enjoyed a<br />

delightful weekend of art,<br />

botany walks, and marionette<br />

shows, with artists donating<br />

30 percent of sale proceeds to<br />

benefit MPF’s prairie conservation<br />

work.<br />

MPF would not be where it is<br />

today without the generosity of<br />

its members and their passion<br />

for prairie—and the first “<strong>Prairie</strong><br />

Paint Out,” organized by MPF<br />

members Theresa and Joe Long<br />

and Jan Trager, is a shining<br />

example of this spirit. The event<br />

raised nearly $2,000 for MPF,<br />

introduced many people to the<br />

organization for the first time,<br />

and educated event-goers about<br />

the ecological importance of tallgrass<br />

prairie.<br />

“A ‘paint out’ is an art event<br />

with artists painting throughout<br />

the day and also selling works<br />

of art,” explained Theresa, who<br />

along with her husband Joe<br />

hosted the event at their Bethany<br />

Springs Farm near Hermann,<br />

Mo. The farm’s 1874 stone house<br />

is centered on 165 acres where<br />

the couple and their son, botanist<br />

Dr. Quinn Long, have been<br />

encouraging native flora since<br />

1995 by tending and reconstructing<br />

woodland, prairie, and stream<br />

habitats. The natural diversity<br />

and beauty of the farm inspires<br />

Theresa’s nature-themed art.<br />

Theresa’s passion for and<br />

commitment to conservation<br />

of the natural world led her,<br />

together with artist Jan Trager, to<br />

organize Bethany Springs Farm’s

Carol Davit<br />

Carol Davit<br />

carol davit<br />

Carol davit<br />

first “<strong>Prairie</strong> Paint-Out” event, with ten exceptional artists exhibiting and selling paintings and<br />

other works of art, and donating 30% of sale proceeds to MPF.<br />

Theresa, who has been teaching art for 27 years, said, “I enjoy creating art, and am dedicated<br />

to preservation of the natural world. Art with a purpose—specifically the purpose of benefiting<br />

conservation efforts inspires me to contribute to MPF through my work. Knowing that<br />

other artists feel the same, Jan and I worked to organize this event with the hopes that it would<br />

promote greater awareness of the work of MPF while offering visitors a chance to experience<br />

the prairie, enjoy botany walks, and learn about artists’ commitment to the work of MPF.”<br />

Artists showing and selling their art at the <strong>Prairie</strong> Paint Out were Marty Coulter, Billyo<br />

O’Donnell, Theresa Long, Jan Trager, Julie Wiegand, Martha Younkin, Karen Kelly, Pat<br />

Sheppard, Christine Torlina, and Annie Green. Margie Manne sold her local honey in handblown<br />

glass vases and Gail Young sold her locally grown produce and flowers.<br />

“Many people who came to see the art also took guided hikes through the reconstructed<br />

prairie at the farm,” said Jan, “and some who came for the prairie hikes stayed to shop for art.<br />

I was thrilled to sell several of my paintings and make a donation to MPF.” Jan’s husband Dr.<br />

James Trager, an MPF technical advisor and biologist at Shaw Nature Reserve, led hike after<br />

hike through prairie and woodland, together with Dr. Quinn Long of the <strong>Missouri</strong> Botanical<br />

Garden. “It was wonderful to see so many people interested in prairie, and who wanted to<br />

establish a prairie planting of their own,” said James.<br />

In addition to the botany walks and art, MPF members Gary Schimmelpfenig and<br />

Christine Torlina led Earth Walks for families at the event, and Gary performed a charming<br />

show with marionettes he and Christine created. The Hidden Garden, written by the couple,<br />

told the story of John Feugh, an African-American gardener who worked for Henry Shaw at<br />

the <strong>Missouri</strong> Botanical Garden, which was established on former prairie. Also starring were<br />

George Washington Carver, prairie plants, and an elderbery bush. “What a joy to be part of<br />

such a meaningful event to benefit the prairie,” said Gary. “It was fulfilling to let my marionettes<br />

tell their story at such a wonderful venue.”<br />

Save the Dates! Don’t miss the Second Annual <strong>Prairie</strong> Paint Out<br />

at Bethany Springs Farm June 22 and 23, 2013.<br />

carol davit<br />

Clockwise from top left: Theresa Long,<br />

left, with her paintings on the porch of the<br />

farm’s 1874 stone house; one of the many<br />

guided tours of the farm’s prairie planting;<br />

Jan Trager, who organized the event with<br />

Theresa, with her paintings; handmade<br />

marionettes in the show created by Gary<br />

Schimmelphenig and Christine Torlina;<br />

guests relaxing at the farm in front of<br />

Christine Torlina’s handpainted tote bags;<br />

and Dr. James Trager and Dr. Quinn Long,<br />

who led hike after hike through the prairie<br />

planting. Below, Martha Yonkin with her<br />

baskets made from bark, leaves, and plant<br />

fibers. “Exploring creative new ways to<br />

help the environment is both important<br />

and rewarding,” said Christine.<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 7<br />

Carol davit Theresa Long

MPF p r a i r i e protection, education, and outreach<br />

Dr. Tallamy’s lecture was followed by a<br />

book signing, tour of Lincoln University’s<br />

Native Plant Outdoor Laboratory and<br />

reception with an impressive variety of<br />

appetizers made with native plant ingredients,<br />

including honey and mountain<br />

mint ice cream, persimmon cookies, and<br />

stinging nettle cornbread. Pictured above<br />

are from left, Mervin Wallace, owner of<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> Wildflowers Nursery, and Carol<br />

Davit with MPF, two sponsors of the event,<br />

with Dr. Nadia Navarette-Tindall, director<br />

of Lincoln’s Native Plant Program, and<br />

Dr. Douglas Tallamy. Top, native plant<br />

enthusiasts admire Lincoln’s Native Plant<br />

Outdoor Laboratory as they line up to<br />

have their books signed by the author.<br />

Congratulations, Dr. Navarette-Tindall and<br />

Lincoln University!<br />

8 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4<br />

An enthusiastic audience of 300<br />

attended Lincoln University’s<br />

event with Dr. Douglas Tallamy,<br />

author of Bringing Nature Home—<br />

How You Can Sustain Wildlife in<br />

your Backyard, on August 30 in<br />

Jefferson City. MPF was a sponsor<br />

of the event organized by<br />

Lincoln’s Native Plants Program<br />

in the Cooperative Extension<br />

Department.<br />

Dr. Tallamy, professor<br />

and chair of the Department of<br />

Entomology and Wildlife Ecology<br />

at the University of Delaware,<br />

studies plant and insect interactions<br />

and how these interactions<br />

determine the diversity of animal<br />

communities. Dr. Tallamy’s factfilled<br />

and entertaining presentation<br />

elucidated the crucial role we have<br />

in choosing native plants, which<br />

are food for native insects, and which are in turn vital food for birds and<br />

other wildlife, for landscaping projects.<br />

Following the lecture, MPF President Stan Parrish, <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

Department of Conservation Assistant Director Tim Ripperger, and MPF<br />

Executive Director Carol Davit announced the transfer of the Grow Native!<br />

native landscaping marketing and education program from the Department<br />

of Conservation to MPF, complete with a native plant transplanting ceremony<br />

to symbolically give the program a new home.<br />

Grow Native! committee members and Grow Native! professional<br />

members were recognized during the announcement, and Lincoln hosted a<br />

Grow Native! committee meeting following the program. The Grow Native!<br />

committee, made up of native landscaping professionals and MPF board<br />

members, is hard at work to carry out the program. Learn more at www.<br />

grownative.org.<br />

Corey Hale<br />

Bringing Nature Home<br />

Event a Great Success!<br />

Randy Tindall<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Protection<br />

Highlights of June–August<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> Management Work<br />

MPF’s <strong>Prairie</strong> Operations Manager Richard<br />

Datema controlled sericea lespedeza, tall fescue,<br />

and Johnson grass this past summer, searching<br />

for these invasive, non-native plants on more<br />

than 1,600 acres of prairie. This acreage included<br />

MPF’s Friendly, Drovers, Gayfeather, Schwartz,<br />

Golden, Denison, and Lattner <strong>Prairie</strong>s, as well<br />

as land owned by several partners: the <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

Department of Conservation’s Grandfather<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong> and Saeger Woods Conservation Area,<br />

Powell Gardens, Jerry Smith Park owned by<br />

Kansas City Parks and Recreation, and two private<br />

prairie landowners. Richard also controlled<br />

woody growth on Grandfather <strong>Prairie</strong> and along a<br />

mile of fence line at MPF’s Stilwell <strong>Prairie</strong>.<br />

From January through August <strong>2012</strong>, Richard<br />

controlled invading trees from a total of 9,580<br />

feet along fence lines and drainage draws on MPF<br />

prairies and private land neighboring MPF’s<br />

Golden <strong>Prairie</strong>. Also in <strong>2012</strong>, Richard prepared<br />

fire lines and he and volunteers applied prescribed<br />

fire at MPF’s Coyne, Denison, Lattner,<br />

Pennsylvania, and Golden <strong>Prairie</strong>s, as well as at<br />

the Ozark Regional Land Trust’s Woods <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

and two tracts owned by private individuals.<br />

At Stilwell <strong>Prairie</strong>, Richard oversaw the<br />

clearing of approximately 25 acres of trees by a<br />

private contractor, making way for more prairiedependent<br />

plants and animals. Richard also cut<br />

the large elm tree from Friendly <strong>Prairie</strong>, which<br />

recently died, eliminating this ground-nesting<br />

bird predator perch.<br />

Besides his on-the-ground work, Richard<br />

does much work that no one sees: he removes<br />

internal fencing from various tracts and has the<br />

wire recycled, maintains equipment, mixes herbi-<br />

Richard Datema<br />

Blue dye<br />

marks<br />

sericea<br />

lespedeza<br />

that has<br />

been<br />

sprayed.

Brian Edmond<br />

ATCHISON<br />

HOLT<br />

NODAWAY<br />

ANDREW<br />

BUCHANAN<br />

PLATTE<br />

BARTON<br />

WORTH<br />

GENTRY<br />

DEKALB<br />

CASS<br />

BATES<br />

NEWTON<br />

VERNON<br />

JASPER<br />

MCDONALD<br />

HARRISON<br />

DAVIESS<br />

CALDWELL LIVINGSTON<br />

CLINTON<br />

RALLS<br />

CHARITON<br />

MONROE<br />

CARROLL<br />

RANDOLPH<br />

PIKE<br />

RAY<br />

CLAY<br />

AUDRAIN<br />

HOWARD BOONE<br />

SALINE<br />

JACKSON LAFAYETTE LINCOLN<br />

CALLAWAY MONT<br />

GOMERY<br />

HENRY<br />

CEDAR<br />

DADE<br />

LAWRENCE<br />

BARRY<br />

MAP DATA PROVIDED BY CHRIS WIEBERG, MDC.<br />

JOHNSON<br />

ST CLAIR<br />

MERCER<br />

GRUNDY<br />

POLK<br />

STONE<br />

PETTIS<br />

BENTON<br />

HICKORY<br />

GREENE<br />

PUTNAM<br />

SULLIVAN<br />

LINN<br />

DALLAS<br />

CHRISTIAN<br />

TANEY<br />

COOPER<br />

MORGAN<br />

CAMDEN<br />

WEBSTER<br />

MACON<br />

SCHUYLER<br />

SCOTLAND<br />

ADAIR<br />

MONITEAU<br />

LACLEDE<br />

MILLER<br />

WRIGHT<br />

DOUGLAS<br />

OZARK<br />

COLE<br />

PULASKI<br />

HOWELL<br />

SHANNON<br />

OREGON<br />

These prairies by MPF and later sold to<br />

the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation<br />

Presettlement <strong>Prairie</strong>. Of these original 15 million acres, fewer than 90,000 acres remain.<br />

KNOX<br />

SHELBY<br />

MARIES<br />

TEXAS<br />

CLARK<br />

OSAGE<br />

LEWIS<br />

MARION<br />

GASCONADE<br />

Throughout its 46 years,<br />

MPF has acquired more<br />

than 3,300 acres of prairie<br />

for permanent protection.<br />

With the conveyance of more<br />

than 700 of these acres to<br />

the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of<br />

Conservation, MPF currently<br />

ST CHARLES<br />

WARREN owns more than 2,600 acres in<br />

15 tracts of land, clears trees<br />

ST LOUIS<br />

FRANKLIN<br />

on properties neighboring<br />

JEFFERSON<br />

MPF land to expand grassland<br />

habitat, and provides<br />

CRAWFORD WASHINGTON<br />

PHELPS<br />

STE GENEVIEVE<br />

management services for<br />

ST FRANCOIS<br />

PERRY<br />

IRON<br />

thousands of additional<br />

DENT<br />

MADISON<br />

CAPE<br />

acres REYNOLDS owned by other GIRARDEAUprairie<br />

partners.<br />

CARTER<br />

RIPLEY<br />

WAYNE<br />

BUTLER<br />

BOLLINGER<br />

DUNKLIN<br />

STODDARD<br />

NEW<br />

MADRID<br />

PEMISCOT<br />

SCOTT<br />

MISSISSIPPI<br />

Ecologists rank temperate grasslands—which include <strong>Missouri</strong>’s tallgrass prairies—as<br />

the least conserved, most threatened major habitat type on earth. <strong>Prairie</strong> protection<br />

efforts in <strong>Missouri</strong>, therefore, are not only essential to preserving our state’s natural<br />

heritage, but also are significant to national and even global conservation work.<br />

MPF is the only organization in the state dedicated exclusively to the conservation of<br />

prairie and other native grasslands.<br />

MPF’s Friendly <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

cide to the proper concentration, documents<br />

his work, and many other important tasks.<br />

Funding for our prairie protection work<br />

in <strong>2012</strong> was provided by you, our valued<br />

members, grants from the Audubon Society<br />

of <strong>Missouri</strong>, the National Wild Turkey<br />

Federation, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Bird Conservation<br />

Initiative grant program, the U.S. Fish<br />

and Wildlife Service Partners for Wildlife<br />

Program, the Wildlife Diversity Fund grant<br />

program, and cost-share funds from the<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation.<br />

Bruce Schuette<br />

Illustration of lark sparrow by Kristen Williams, published in Birds in <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

by Brad Jacobs, 2001 Conservation Commission of the State of <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

Lark sparrows are uncommon<br />

summer residents in <strong>Missouri</strong>,<br />

where they can be seen foraging<br />

on the ground for insects and<br />

seeds in open farmland, prairies,<br />

roadsides and woodland edges.<br />

MPF Technical Advisor documented<br />

two breeding pairs of the birds at<br />

MPF’s Stilwell <strong>Prairie</strong> in June, as<br />

well as two fledglings.<br />

MPF Bird Survey<br />

Reveals Lark Sparrows<br />

and More!<br />

Last June, MPF Technical Advisor Jeff<br />

Cantrell conducted bird surveys on<br />

nine MPF prairies, private land next to<br />

MPF’s Golden <strong>Prairie</strong>, and <strong>Prairie</strong> State<br />

Park. The survey, part of MPF’s Fiscal<br />

Year <strong>2012</strong> <strong>Missouri</strong> Bird Conservation<br />

Initiative grant obligation, provided helpful<br />

data on the presence and abundance<br />

of grassland bird species.<br />

Jeff documented 45 total bird species,<br />

including lark sparrows, northern<br />

bobwhites, and grasshopper sparrows. Jeff<br />

will conduct similar surveys on the same<br />

prairies this winter to document bird<br />

presence and abundance. Many thanks<br />

to Jeff, who took vacation time from his<br />

work to conduct the surveys.<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 9

MPF p r a i r i e protection, education, and outreach<br />

New<br />

Species of<br />

Conservation<br />

Concern<br />

Found on<br />

MPF <strong>Prairie</strong>s<br />

10 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4<br />

The Arkansas darter is among the recently documented<br />

species of conservation concern found on MPF prairies.<br />

MPF properties had been known to provide habitat for at least 12 species of<br />

conservation concern, including the state-listed regal fritillary butterfly and<br />

northern crawfish frog, and the federally threatened Mead’s milkweed and<br />

the tiny wildflower Geocarpon minimum, known from only 50 locations on<br />

the planet. Recently, biologists have documented additional species of conservation<br />

concern on MPF prairies.<br />

During the 2010 BioBlitz held at Penn-Sylvania <strong>Prairie</strong>, Justin Thomas,<br />

with the Institute for Botanical Training, documented Juncus debilis, a statelisted<br />

rush, growing on the prairie. Its official rank is “critically imperiled” in<br />

the state. During the Golden <strong>Prairie</strong> BioBlitz held last year, fisheries biologists<br />

Tom Preisendorf and Kara Tvedt found Arkansas darters (Etheostoma<br />

cragini), ranked “vulnerable” in <strong>Missouri</strong> and a candidate for federal listing.<br />

During the BioBlitz held this past June at Schwartz <strong>Prairie</strong>, John Atwood<br />

and Nels Holmberg found a moss, Pohlia annotina, state-listed as “SU,”<br />

meaning so little is known about the species that it can not be ranked. Also<br />

at Schwartz, Justin Thomas documented Eleocharis lanceolata, a state-listed<br />

spike rush.<br />

MPF’s careful management and aggressive control of invasive species<br />

maintains vital habitat for these species of conservation concern and thousands<br />

of other plants and invertebrate and vertebrate animals that depend on<br />

high quality prairie.<br />

New Signage at MPF’s<br />

La Petite Gemme <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

At 37 acres, La Petite Gemme is truly a<br />

small gem of a prairie. The Frisco Highline<br />

Trail—a national recreation trail—runs<br />

through this designated <strong>Missouri</strong> Natural<br />

Area in Polk County. New signs developed<br />

by Ozark Greenways, with content input and partial funding provided by<br />

MPF, help interpret the prairie landscape to trail users. The 35-mile trail<br />

connects Springfield and Bolivar. For more information visit www.friscohighlinetrail.org.<br />

Susan Parrish<br />

Gary House<br />

Private Land Conservation<br />

Focus of <strong>2012</strong> MOBCI<br />

Conference<br />

To date, 62 organizations—including MPF<br />

and other private conservation groups and public<br />

land management agencies—have signed a<br />

Memorandum of Agreement to participate in the<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> Bird Conservation Initiative. The purpose<br />

of the group, also known as MOBCI, is to<br />

combine efforts to conserve bird populations and<br />

their habitats.<br />

MOBCI held its annual conference August<br />

17 and 18, the theme being “This Land is Your<br />

Land; This Land is my Land: The importance of<br />

Private Land Management and the Development<br />

of a Strong Land Ethic.” Among the many talks<br />

was a presentation by MPF’s Carol Davit on<br />

MPF’s prairie conservation.<br />

Lisa Potter, who coordinates Farm Bill<br />

information for the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of<br />

Conservation, gave a presentation on the status<br />

of the <strong>2012</strong> Farm Bill, and the conservation measures<br />

at stake in this legislation that will affect the<br />

future of conservation. Lisa explained that the<br />

2008 Farm Bill expires September 30, <strong>2012</strong>, and<br />

authorized $23 billion for conservation programs<br />

nationwide over five years. The Farm Bill is the<br />

single largest source of conservation funding<br />

available to assist private landowners in restoring,<br />

protecting, and enhancing soil quality, water<br />

quality, and wildlife habitat.<br />

Lisa also explained that the <strong>2012</strong> Farm Bill<br />

may not be passed until after the November<br />

election. The draft of the new bill cuts $23 to<br />

$35 billion in total spending, with a $6 billion<br />

cut (10%) in conservation programs. Other<br />

proposed changes include a nationwide reduction<br />

of the total acreage allowed in the Conservation<br />

Reserve Program from 32 million acres to 25<br />

million acres; consolidation of the EQIP and<br />

WHIP programs, with recreational landowners<br />

becoming potentially ineligible to enroll; and<br />

the requirement of a third party easement holder<br />

that provides a 50:50 funding match with<br />

USDA grassland (GRP) and farmland (FRPP)<br />

easements.<br />

As of September 24, the fate of the <strong>2012</strong><br />

Farm Bill and its conservation programs is uncertain.<br />

By contacting your elected officials, you can<br />

let them know how important robust conservation<br />

programs in the next Farm Bill are to you.

<strong>2012</strong><br />

Campaign for <strong>Prairie</strong>s<br />

Please keep the natural wealth of our prairies in mind when you<br />

consider your end-of-year charitable giving. With no office and only<br />

two staff members, the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation’s (MPF’s) overhead is low, and directs all<br />

contributions to fulfilling our on-the-ground conservation, education, and outreach work.<br />

MPF’s <strong>2012</strong> fundraising goal to cover all expenses is $250,000. With your help, we have<br />

accomplished an impressive amount of work this year—including on-going prairie<br />

protection, advocacy for native grassland-friendly conservation policies, and expansion<br />

of native plant promotion through the Grow Native! program.<br />

We hope you can support our conservation<br />

work with a tax-deductible donation.<br />

Please mail your gift to<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation<br />

c/o Martinsburg Bank<br />

P.O. Box 856<br />

Mexico, MO 65265-0856<br />

To make a gift of securities, please contact<br />

MPF at 888-843-6739.<br />

Thank you for your continued support<br />

of <strong>Missouri</strong>’s prairies. We can’t do our<br />

work without you.<br />

Allen Woodliffe<br />

“I am so impressed by what the<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Foundation<br />

accomplishes with such a small<br />

budget and so little staff. You<br />

should get some kind of efficiency<br />

award—you are raising the bar<br />

for charity efficiency. Keep up the<br />

good work.”<br />

—Francine Cantor, MPF member, St. Louis, MO<br />

“I’ve enjoyed reading several recent<br />

issues of the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong><br />

Journal more than any other<br />

magazine in recent memory. And<br />

I subscribe to The Economist,<br />

Bird Watchers Digest, National<br />

Geographic, Environmental<br />

History and a half dozen others<br />

that are pretty good reading. Not<br />

only is the content interesting and<br />

readable, but the design is also<br />

excellent.”<br />

—Dr. Rupert Cutler, MPF member, Roanoke, VA.<br />

(former editor of Virginia Wildlife, managing editor of<br />

National Wildlife, president of Defenders of Wildlife,<br />

and assistant secretary of agriculture in charge of the<br />

USDA Forest Service in the Carter Administration)<br />

Noppadol Paothong/MDC<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 11

Five Years of Greater<br />

<strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Translocation<br />

This year caps the end of the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation’s greater prairie-chicken<br />

translocation project, an effort to increase populations of these magnificent grassland birds in <strong>Missouri</strong>.<br />

By Max Alleger<br />

One of the walk-in trap arrays used for greater<br />

prairie-chicken trapping in Kansas. The<br />

translocation team constructed the traps on<br />

leks; as the birds walked onto or across the<br />

booming ground, they encountered the lead<br />

wire, which led them into the trap boxes.<br />

Being trapped didn’t deter males from<br />

booming, which sometimes attracted hens to<br />

the tops of the trap boxes.<br />

NOPPADOL PAOTHONG/MDC<br />

NOPPADOL PAOTHONG/MDC<br />

Over the past five years, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of<br />

Conservation (MDC) has conducted an experimental<br />

greater prairie-chicken translocation project to determine if<br />

reintroduction is an effective part of ongoing recovery efforts.<br />

Wah’Kon-Tah <strong>Prairie</strong>, a 3,030-acre tract jointly owned by The Nature Conservancy<br />

of <strong>Missouri</strong> and MDC, was selected as the release site due to the tract’s extent of well<br />

managed native prairie and other grasslands, its proximity to native greater prairiechickens<br />

at Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong>, the expertise of local managers, and a history of interest<br />

in prairie and grassland conservation among local landowners.<br />

Greater prairie-chickens disappeared from Wah’Kon-Tah by 2000. This was prior<br />

to the implementation of intensive grassland management efforts, thus providing an<br />

opportunity in 2008 to reintroduce the birds to an uninhabited landscape and monitor<br />

their habitat use preferences and determine their site fidelity, survival, and productivity<br />

under modern <strong>Missouri</strong> conditions.<br />

How to Catch a <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken<br />

A team of MDC biologists and supervised volunteers conducted trapping in a<br />

580-square-mile area of Kansas’ Smoky Hills Region from 2008 to <strong>2012</strong>. The team<br />

trapped greater prairie-chickens from 46 of 86 known booming grounds, also called<br />

leks, which were closely monitored throughout the project. Most leks were located on<br />

privately owned land, which required close coordination with more than 60 Kansas<br />

ranchers and farmers.<br />

For the first three years of the project, biologists conducted translocation in a<br />

two-stage process. During spring, the translocation team captured greater prairiechickens<br />

on leks using walk-in traps, which were linked by sometimes elaborate arrays<br />

of chicken-wire leads. Upon arrival at a new site, trapping teams looked more like<br />

fence construction crews than wildlife biologists. The configuration and construction<br />

of trap arrays was more art than science, and tweaking the arrangement of traps and<br />

lead wires was often necessary.<br />

Team members transported males to <strong>Missouri</strong> for release at Wah’Kon-Tah within<br />

six to eight hours of capture. Females were radio-marked and immediately released at<br />

the capture site to nest in their native landscape.<br />

Trappers returned to Kansas in late July to recapture radio-marked hens and their<br />

broods as they roosted in grazed pasture and weedy Conservation Reserve Program<br />

(CRP) fields. Summer capture teams included an experienced telemetry technician<br />

and four to six net-wielding biologists whose nightly excursions entailed walking miles<br />

of native rangeland in the pitch dark. We worked quietly, except for the occasional<br />

exclamation when someone stepped in a badger hole, sarcastic ribbing when a team<br />

member missed a bird, and incessant whining when the wind laid down enough to<br />

12 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4

allow mosquitoes to swarm. We used<br />

glow-sticks and an ever-evolving series<br />

of hand signals to communicate as<br />

we made our final capture approach.<br />

Roughly a third of hens captured in<br />

spring were recaptured during summer<br />

night-lighting annually; about a third of<br />

all capture attempts was successful.<br />

In 2010, small, glue-on transmitters<br />

were placed on summer-captured<br />

juveniles for the first time. Due to<br />

higher-than expected mortality among<br />

translocated juveniles following their<br />

release, the two-phase translocation<br />

process was discontinued. During 2011<br />

and <strong>2012</strong>, all birds were brought to<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> during spring. Overall, 435<br />

birds were translocated between 2008<br />

and <strong>2012</strong>. Greater prairie-chickens are<br />

relatively short-lived; even on good habitat<br />

most do not survive past two years.<br />

As a result, the offspring of translocated<br />

birds, not the Kansas birds themselves,<br />

comprise the bulk of the population<br />

now residing at and around Wah’Kon-<br />

Tah <strong>Prairie</strong>.<br />

We took a very conservative<br />

approach to trapping individual leks.<br />

No more than 20 percent of males were<br />

removed from a lek in any year, and<br />

we avoided removing dominant males<br />

to help maintain the established social<br />

order on the lek. This required trappers<br />

to tear down and rebuild trap arrays<br />

nearly every day, but this labor-intensive<br />

approach helped assure that counts on<br />

Kansas leks remained stable throughout<br />

the project. We also spread trapping<br />

across a larger area each year to minimize<br />

potential negative impacts to the<br />

Kansas population.<br />

Monitoring Translocated<br />

Birds in <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

Dispersal: Results of translocation projects<br />

conducted by other organizations in<br />

other states indicate that greater prairiechickens<br />

are more likely to disperse from<br />

sites where habitat is dissimilar to that<br />

of their origin, and from sites not occupied<br />

by native birds. We expected some<br />

translocated birds to disperse from the<br />

Wah’Kon-Tah release site.<br />

Greater prairie-chickens translocated by year, sex, and age class.<br />

Year Adult Males Adult Females Juveniles Total<br />

2008 52 24 27 103<br />

2009 50 25 26 101<br />

2010 41 29 18 88<br />

2011 28 53 - 81<br />

<strong>2012</strong> 18 44 - 62<br />

Total 189 175 71 435<br />

NOPPADOL PAOTHONG/MDC<br />

One of six grassland grouse species in<br />

North America, greater prairie-chickens<br />

(Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus) once ranged<br />

throughout native prairies of central<br />

North America from southern Canada to<br />

Texas. Historically, they probably occurred<br />

in 20 states and four Canadian provinces.<br />

However, their distribution has changed<br />

drastically over the past 200 years. Today,<br />

greater prairie-chickens are plentiful<br />

enough to be a game species in Kansas,<br />

Nebraska, and South Dakota, but the birds<br />

are absent from Canada, and only small<br />

populations remain in Wisconsin, Minnesota,<br />

Illinois, Oklahoma, and <strong>Missouri</strong>, where<br />

fewer than 100 individuals native to the<br />

state still survive.<br />

Greater prairie-chicken trapping locations in<br />

the Smoky Hills Region of Kansas. New leks<br />

were trapped each year to assure a conservative<br />

approach. Trapped birds were transported<br />

to Wah’Kon-Tah within six to eight<br />

hours of capture.<br />

Kansas Leks Trapped &<br />

Hen/Chick Capture Locations 2009<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 13

NOPPADOL PAOTHONG/MDC<br />

MDC’s Aimee Coy<br />

set up decoys and<br />

played recordings<br />

of prairie-chicken<br />

booming on Wah’Kon-<br />

Tah to simulate a<br />

lek and help draw<br />

translocated males to<br />

the historic lek site.<br />

Dispersal of translocated greater prairiechickens<br />

in <strong>Missouri</strong> from 2008 to <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

Although most birds remained<br />

on or very near Wah’Kon-Tah, telemetry<br />

confirmed that some did disperse<br />

beyond the release landscape. Dispersing<br />

individuals moved up to 30 miles or<br />

more, across rivers, roads, and woodlands.<br />

Their ability to navigate across the<br />

countryside and their choices to settle in<br />

at places that had held prairie-chickens<br />

in decades past was uncanny. Notable<br />

case studies of individual dispersal<br />

include:<br />

• A male translocated in 2010 flew to<br />

Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong> and, within days of<br />

release, became the dominant cock on<br />

the established lek of native birds.<br />

• A hen flew to Walker, nine miles west<br />

of Wah’Kon-Tah, and successfully<br />

hatched a brood on private land in<br />

2011. She remained in the Walker<br />

area until <strong>2012</strong>, when she returned to<br />

Wah’Kon-Tah and hatched a successful<br />

brood.<br />

• A hen flew to Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong>,<br />

then to Niawathe <strong>Prairie</strong> during the<br />

same month in the winter of 2011.<br />

She spent the winter on and around<br />

Niawathe, mated with the lone male<br />

on nearby Horse Creek <strong>Prairie</strong>, then<br />

nested and hatched a brood of 14<br />

chicks on Shelton <strong>Prairie</strong> during the<br />

spring of <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

• A hen translocated during <strong>2012</strong> flew to<br />

the Walker vicinity in late April, disappeared<br />

for two weeks, and was then<br />

located via helicopter telemetry north<br />

of Fort Scott, Kansas.<br />

• A hen translocated during <strong>2012</strong> flew<br />

to Butler, Mo. and then returned to<br />

Wah’Kon-Tah to mingle with the<br />

newly established flock.<br />

Lek Establishment: Prior to our initial<br />

2008 release, three simulated leks were<br />

established to mimic habitat occupancy,<br />

a cue that released birds often use to<br />

determine initial habitat suitability.<br />

Simulated leks consisted of silhouette<br />

decoys of displaying males and broadcast<br />

calls of booming and cackling. Eight<br />

recently released males displayed on two<br />

of the three simulated leks during 2008.<br />

Four males released in 2008 also<br />

established a lek at Wah’Kon-Tah<br />

and continued their courtship display.<br />

During spring 2009, 13 males established<br />

a lek 700 meters southeast of a<br />

simulated lek; this time with a female<br />

audience. In 2010, as many as 22 males<br />

displayed on three booming grounds<br />

at Wah’Kon-Tah. The peak lek count<br />

in 2011 was 20, although lek location<br />

shifted as compared to 2010. During<br />

<strong>2012</strong>, 27 males used the same three leks<br />

established in 2011.<br />

Nest Site Selection: Patterns of nest<br />

site selection among radio-marked hens<br />

are emerging. However, analysis of<br />

telemetry data is ongoing and definitive<br />

statements related to habitat preferences<br />

cannot yet be made. It appears that<br />

management treatments such as patchburn<br />

grazing and high-clipping, which<br />

reduce the height and density of herbaceous<br />

vegetation, do influence nest site<br />

selection. Documenting how the juxtaposition<br />

of areas receiving such management,<br />

and time elapsed since treatment,<br />

impact nest site selection remains an<br />

important monitoring objective that will<br />

guide future management.<br />

Anecdotal observation indicates<br />

that a majority of nests are located<br />

near an herbaceous edge (soft edge), as<br />

defined by a visually significant change<br />

in herbaceous vegetation structure. Soft<br />

edge is often associated with cattle or<br />

vehicle trails or firelines, as well as where<br />

boundaries of differently managed units<br />

meet. Observations thus far suggest that<br />

management history and vegetation<br />

height influence nest site selection.<br />

Nest Fate: During 2009, apparent nest<br />

success among translocated females was<br />

comparable to that reported by studies<br />

of resident birds. Apparent nest success<br />

from 2010–<strong>2012</strong> was higher than that<br />

expected among native greater prairiechickens.<br />

Fewer nests were monitored<br />

during <strong>2012</strong> than in 2011 because fewer<br />

females were translocated during <strong>2012</strong><br />

(44) than in 2011 (60).<br />

14 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4

Fate of 67 nests of radio-collared hens monitored from 2009 to <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

Area<br />

# 2009<br />

Nests<br />

# 2009<br />

Successful<br />

# 2010<br />

Nests<br />

# 2010<br />

Successful<br />

# 2011<br />

Nests<br />

# 2011<br />

Successful<br />

# <strong>2012</strong><br />

Nests<br />

Wah’Kon-Tah 4 3 6 5 22 15 11 9<br />

Taberville 4 2 4 3 8 5 6 6<br />

Walker 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0<br />

Shelton 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1<br />

Totals 8 5 10 8 31 21 18 16<br />

# <strong>2012</strong><br />

Successful<br />

Telemetry Monitoring Observations:<br />

Tracking radio-marked females and the<br />

fate of their nests and broods has added<br />

to our understanding of the vegetative<br />

cover that greater-prairie chickens prefer<br />

for nesting, raising broods, feeding, and<br />

evading predators. Although additional<br />

monitoring is needed for statistical confirmation,<br />

observations to date indicate<br />

the importance of maintaining a patchwork<br />

of varying herbaceous vegetation<br />

types across large, unfragmented grasslands<br />

of at least several hundred acres.<br />

Prescribed fire, patch-burn grazing, and<br />

high-clipping relatively small, 40- to<br />

80-acre units within larger grassland<br />

landscapes all appear important to create<br />

and maintain this variety of herbaceous<br />

cover heights and densities. Additional<br />

telemetry monitoring observations<br />

include:<br />

• Given comparatively poor survival<br />

among translocated juveniles, spring<br />

translocation is recommended over the<br />

two-phase approach, which included<br />

summer recapture of previously radiomarked<br />

females and their broods.<br />

• Translocation efforts proved successful<br />

in terms of lek establishment, site fidelity,<br />

and production at Wah’Kon-Tah<br />

and interaction with native birds at<br />

Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong> (Jamison and Alleger<br />

2009).<br />

• Dispersal rates are higher and survival<br />

is lower among first-year translocated<br />

birds compared to resident birds<br />

(Kemink <strong>2012</strong>).<br />

• The acclimation period over which<br />

translocated birds experience depressed<br />

survival is approximately six months<br />

(Kemink <strong>2012</strong>).<br />

• Increasing winter flock numbers at<br />

Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong> indicate an increase<br />

in bird recruitment from local subpopulations.<br />

It is not known whether<br />

this is a direct result of translocation.<br />

• <strong>Winter</strong> trapping documented successful<br />

brood-rearing at Wah’Kon-Tah, as<br />

juvenile birds lacking transmitters and<br />

leg bands have been observed and/or<br />

trapped.<br />

• With regard to the Partners in Flight<br />

Grassland Bird habitat model (PIF<br />

Model), birds prefer Departmentmanaged<br />

“core” habitat, and survival<br />

is lower on smaller, privately owned,<br />

“satellite” tracts (Kemink <strong>2012</strong>).<br />

• The presence of fences and trees<br />

reduces the amount of usable space<br />

(Kemink <strong>2012</strong>).<br />

• Future translocation efforts should<br />

consider releasing larger numbers of<br />

birds, biased toward females (Kemink<br />

<strong>2012</strong>).<br />

MDC staff will continue monitoring<br />

this re-established population at<br />

Wah’Kon-Tah to evaluate the long-term<br />

effectiveness of translocation as a greater<br />

prairie-chicken recovery tool. <strong>Winter</strong><br />

trapping will continue at Wah’Kon-Tah<br />

and Taberville prairies over the next<br />

four years to further document individual<br />

survival, nest site selection and<br />

success, and brood survival, with special<br />

emphasis on understanding habitat<br />

While habitat preference data are still being<br />

analyzed, it appears that management<br />

treatments such as patch-burn grazing and<br />

high-clipping, shown above, which reduces<br />

the height and density of vegetation, influence<br />

prairie-chicken nest site selection.<br />

selection patterns. This documentation<br />

will inform future management methods<br />

and priorities. Lek counts will help<br />

determine post-translocation population<br />

stability.<br />

Thinking Forward<br />

This translocation project has succeeded<br />

in reestablishing a functional greater<br />

prairie-chicken population at Wah’Kon-<br />

Tah. The long-term stability of that<br />

population hinges on the continuation<br />

of intensive grassland management on<br />

MDC-managed lands, as well as upon<br />

further efforts to reduce fragmentation<br />

and add viable nesting and brood-rearing<br />

cover on nearby private lands.<br />

Each time I’ve returned home<br />

from greater prairie-chicken trapping<br />

I’ve been struck by the daunting difference<br />

in scale between our grasslands<br />

and those in Kansas’ Smoky Hills. Do<br />

we have enough unfragmented prairie<br />

Steve CLubine<br />

Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal 15

and other grasslands to sustain greater<br />

prairie-chickens in <strong>Missouri</strong>? Can we<br />

expand what we do have, and manage it<br />

to provide the mix of vegetation types<br />

and structures needed by greater prairiechickens<br />

and other grassland birds?<br />

Can we engage farmers and ranchers<br />

to improve grassland bird habitat in an<br />

era when high commodity prices drive<br />

private land management relentlessly<br />

toward maximum production? Will current<br />

recovery efforts someday be viewed<br />

as a positive turning point, or as the last<br />

dash in a long but futile race? I remain<br />

hopeful for positive outcomes, but see<br />

a clear need for open minds and new<br />

approaches.<br />

The issues represented by the need<br />

for a greater prairie-chicken recovery<br />

effort—and the importance of evaluating<br />

translocation as a strategy within<br />

that larger effort—go well beyond the<br />

needs of the species, as many grassland<br />

birds and other grassland plants and<br />

animals are in peril. Those of us closely<br />

linked to this project recognized early<br />

on that success would require striking<br />

a sustainable balance between strictly<br />

preservationist ideals and reckless exploitation;<br />

neither of those extremes can<br />

maintain the integrity of inherently<br />

dynamic grassland systems. Finding this<br />

balance will require a more purposeful<br />

cross-pollination of the ideas and ideals<br />

that drive conservationists and the farmers<br />

and ranchers who control a majority<br />

of our grasslands.<br />

Engaging the consumers who drive<br />

our economic system seems an essential<br />

step as well. If current greater prairiechicken<br />

recovery efforts are to succeed,<br />

more farmers must begin to see longterm,<br />

intrinsic value in the species and<br />

natural processes that share their land as<br />

surely as more prairie enthusiasts must<br />

come to value the fact that healthy calves<br />

and positive balance sheets support<br />

stable land tenure, which is essential to<br />

an ability to plan and manage land for<br />

long-term benefits. Our ability to grapple<br />

with issues like these will determine<br />

whether our grandchildren, and theirs,<br />

will see prairie-chickens in <strong>Missouri</strong>.<br />

Citations<br />

Jamison, B.E. and M.R. Alleger. 2009. Status of<br />

<strong>Missouri</strong> greater prairie-chicken populations<br />

and preliminary observations from ongoing<br />

translocations and telemetry. Grouse News.<br />

13 pages.<br />

Kemink, K. M. <strong>2012</strong>. Survival, habitat use, and<br />

movement of resident and translocated<br />

greater prairie-chickens. Master’s Thesis,<br />

University of <strong>Missouri</strong>, Columbia, USA.<br />

Max Alleger is the grassland bird<br />

coordinator for the Mo. Dept. of<br />

Conservation and an MPF technical advisor.<br />

A Big Thank You to Smoky Hills Landowners<br />

Public agency staff and private landowners in the Smoky<br />

Hills of Kansas made the translocation project possible.<br />

By Steve Clubine<br />

From left are members of the 2008 trapping<br />

crew (Monte McQuillen, Matt Hill, with MDC;<br />

volunteer and MPF member Donnie Nichols;<br />

Max Alleger, with MDC), Kansas landowner<br />

Gordon McClure, who helped the <strong>Missouri</strong><br />

crew contact landowners with greater<br />

prairie-chicken leks, and Steve Clubine.<br />

Max ALleger<br />

Before I retired from the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation (MDC) in<br />

2010, I had the honor of overseeing the translocation portion of MDC’s<br />

2005 <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Recovery Plan. In 2008, Max Alleger and I began<br />

talking to state agency representatives in Kansas and Nebraska about translocating<br />

birds from those states.<br />

After considering impacts to populations of the birds, travel time, land management<br />

practices in these states, and several other factors, we settled on the northern<br />

Flint Hills and the Smoky Hills regions of Kansas. We obtained permission to trap<br />

birds at the U.S. Army’s Fort Riley and the Air National Guard’s Smoky Hill Range<br />

near Salina. Fort Riley is 106,000 acres in the Flint Hills, but access to much of it<br />

became so limited due to training maneuvers that we abandoned trapping efforts after<br />

the first spring.<br />

The Air National Guard Range is 34,000 acres of tall to mid-grass prairie, about<br />

half moderately grazed, a fourth annually hayed, and a fourth, the central impact<br />

zone, annually burned. Air National Guard officials initially allowed us to have up to<br />

30 birds annually. However, after the first year, our quota was cut to 15 birds for the<br />

second and third year and none for the fourth and fifth years.<br />

16 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal Vol. <strong>33</strong> Nos. 3 & 4

Max ALleger<br />

For the rest of our annual 100-bird<br />

quota, I began searching land west and<br />

north of the Air National Guard Range.<br />

Native rangeland in the Smoky Hills<br />

doesn’t get as much rain (about 25 inches<br />

annually) and burning is not as widespread<br />

or as frequent—about once every<br />

4 to 10 years. Also, cropland enrolled<br />

in the Conservation Reserve Program<br />

(CRP) was planted to a native mix of<br />

grasses and forbs or to smooth bromegrass.<br />

In average or above average rainfall<br />

years, native plantings may be too<br />

tall for chickens, but are a much more<br />

appropriate height in dry years when<br />

nearby rangeland may be grazed too<br />

short. Thus CRP may help keep Smoky<br />

Hills’ greater prairie-chicken populations<br />

from declining during dry years.<br />

While driving a Saline County road<br />

looking and listening for booming, I met<br />

Brent Laas, a local farmer and stockman,<br />

who asked me if I was lost. I said, “I<br />

know where I am, but I’m looking for<br />

folks like you who could help me find<br />

prairie-chicken booming grounds.” He<br />

said he knew of a large lek by a house he<br />

owned and I was welcome to take some<br />

of those birds if his brother, daughter,<br />

some other relatives, friends, and he<br />

could watch how the heck I intended<br />

to catch the birds. Our efforts provided<br />

several hours of entertainment for them.<br />

Satisfied we knew what we were<br />

doing, Brent said he thought there was<br />

a large lek north of I-70 in Glendale<br />

Township where he cut prairie hay. That<br />

was the beginning of a series of events<br />

that literally opened the doors to other<br />

Smoky Hills ranches. I went to Glendale<br />

Township the next morning and found a<br />

lek of <strong>33</strong> males on a wheat field, which,<br />

ironically, was owned by St. Louis attorney<br />

Maurice Springer. Further searching<br />

revealed several smaller leks. I began<br />

contacting landowners and they told me<br />

other places to look. Two landowners<br />

in particular, Gordon McClure and Hal<br />

Berkley, owned a lot of land and knew<br />

a lot of landowners. If I found a place I<br />

wanted to look, I was to tell the owners<br />

I was working with them. Further, if I<br />

needed a phone number they usually<br />

had it on their cells. One of the ranchers<br />

Gordon suggested we talk to Dick<br />

Dietrich who owned or leased thousands<br />

of acres of rangeland north of Tescott.<br />

Gordon also provided his farm headquarters<br />

for temporary storage of traps,<br />

wire, and equipment, and loaned me a<br />

fence charger to put a hotwire around<br />

leks where cattle were present.<br />

I also contacted Sandy Walker,<br />

manager of Rolling Hills Wildlife<br />

Adventures west of Salina, about a lek<br />

on her land. Sandy asked if we needed<br />

health inspections on the birds. While<br />

we didn’t have to, we did take Sandy<br />

up on her offer of the services of her<br />

resident vet, Danelle Okeson. Danelle<br />

had done Ph.D. work on Attwater’s<br />

prairie-chickens near Houston so was<br />

very familiar with prairie-chicken health.<br />

Danelle was a great trooper, even meeting<br />

me at a Salina truck stop between<br />

2:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. in the summer<br />

when we were transporting hens and<br />

chicks.<br />

Max ALleger<br />

Dr. Danelle Okeson, a vet from the Smoky Hills,<br />

volunteered to conduct health inspections of the<br />

birds to be translocated to <strong>Missouri</strong>. Dr. Okeson was<br />

a trooper, even meeting the crew at a truck stop at<br />

2:00 a.m. to examine trapped birds.<br />

Greater prairie-chickens fly above the wide open<br />

landscape of Kansas’ Smoky Hills Region of tall and<br />

mid-grass prairie.<br />

We provided every landowner on<br />

whose land we worked written documentation<br />

of exactly what we caught,<br />

took back, and released. We entered no<br />

land without landowners’ knowledge<br />

and we reported anything out of the<br />

ordinary, a calf out or down, broken<br />

fence wire, etc., and every gate was shut<br />

unless we found it open in which case<br />

we checked with them to make sure it<br />

was to be left open.<br />

Our trapping experience resulted<br />

in an extraordinarily good working relationship<br />

with landowners and Danelle.<br />

Over 60 landowners or their ranch<br />

managers trusted us and our word, giving<br />

us access to their land day and night.<br />

We were turned down only a handful<br />

of times and those by landowners who<br />

wanted to make sure the birds remained<br />

in good numbers where they were. Most<br />

landowners were happy that they could<br />

contribute to restoring a new population<br />

elsewhere and wanted to know how<br />

they were doing and how we planned to<br />

make sure they didn’t die out again. The<br />

latter may be our biggest challenge.<br />

Steve Clubine served as the grassland<br />

biologist for the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of<br />

Conservation until retiring in 2010. His<br />

“Native Warm-Season Grass News”<br />

(see page 25) is a regular feature<br />

of the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal.<br />