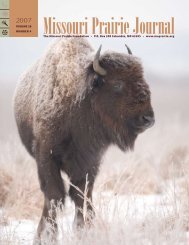

Summer 2007: Volume 28, Number 3 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Summer 2007: Volume 28, Number 3 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Summer 2007: Volume 28, Number 3 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Contents<strong>Summer</strong><strong>2007</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> <strong>28</strong>, <strong>Number</strong> 3The mission of the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong><strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) isto protect and restoreprairie and other nativegrassland communitiesthrough acquisition,management, educationand research.614Message from the President 2Feature Articles<strong>Summer</strong> MeetingMembers and guests gatherat Friendly <strong>Prairie</strong> 4Public Assistancefor Private <strong>Prairie</strong> ConservationA Beginner’s Guide, Part II of II 6Innovation in Bloom: My Monthas a Kinship Conservation Fellow 12St. Louis Area Urban <strong>Prairie</strong>s 144The <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong>Journal is publishedquarterly by the <strong>Missouri</strong><strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>.Please send materialsfor the fall <strong>2007</strong> issueby October 1, <strong>2007</strong> toCarol DavitJournal editor1311 Moreland AvenueJefferson City, MO 65101Phone: 573-893-5446davitleahy@earthlink.netThe <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong>Journal is designedby Tracy Ritter.To become an MPFmember or givethe gift of MPFmembership, pleasecall 1-888-843-6739 or573-356-78<strong>28</strong>.Map of MPF <strong>Prairie</strong>s 2526A Rich Man’s GardenOn a Teacher’s Pension 26Richard’s <strong>Prairie</strong> Management Advice 31Calendar of <strong>Prairie</strong>-Related Events 32Pure <strong>Prairie</strong> 34<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> Officers,Directors and Advisors Back coverOn the coverHoary vervain (Verbenastricta) is common yetbeautiful in prairies,pastures and fields. Itblooms from late springto early fall. Photo byNoppadol Paothong/MDC.More of his photos appearthroughout this issue.

<strong>Summer</strong> Meeting Members and guestsBy Justin JohnsonCasey GalvinAlong with the wavinggrasses, several redflags on the area markedoccurrences of thefederally threatenedMead’s milkweed(Asclepias meadii),pictured above. Theplant has becomerare over time dueto the overall loss ofnative prairie, habitatfragmentation andearly season haying ofmany remaining prairiesbefore the plant goes toseed. It is also believedthat the small beesthat pollinate Mead’smilkweed are declining.The southern half ofFriendly <strong>Prairie</strong> wasburned by MDC managersthis spring, and theMead’s milkweed plantswere closely monitoredthrough the summer;however, none ofthe plants producedsuccessful seedpods.The <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>(MPF) held its summer boardmeeting at Friendly <strong>Prairie</strong> southof Sedalia on August 18. Field conditionswere lush, as June rain and summer heatcombined to produce tall, thick grassat the 40-acre site, which is owned byMPF and cooperatively managed by the<strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation(MDC).As Membership Grows,MPF Changes Policies and StrategyMPF President Steve Mowry noted that thefoundation has made progress toward its goal of5,000 members by January 1, 2010. In August2005, MPF had 2,300 members and two yearslater that total is 3,300, an all-time high. Inresponse to concerns expressed by some MPFmembers, the board voted to change its policyregarding donations and the general membershipcycle. Effective this year, a donation of $25 ormore, whether intended for general membershipor a specific purpose, such as the Coyne <strong>Prairie</strong>acquisition, will be treated as a membershiprenewal. In the past, members who contributedto specific campaign appeals during the year wereoften confused by general membership renewalrequests once every 12 months. The change ispart of a general board policy shift to send fewergeneral membership renewal mailings and insteadsend a few action-oriented requests each yearpaul coxto all members. Beginning with the fall <strong>2007</strong>issue, more than 900 landowners in GrasslandsCoalition Focus Areas will receive four trial issuesof the Journal. Many former MPF members, wholikely have not seen a Journal since the switchto full-color format in the spring 2006, will alsoreceive a complimentary issue and an invitation tore-join.Resources Available On-lineFull electronic copies of the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong>Journal from summer 2003 to the present arenow available at www.moprairie.org. In addition,land management advice and scientific studies arebeing added to the management, education andresearch sections of the Web site. If there is somethingyou would like to see added on-line, visitthe MPF Web site and click on the “Contact”link.<strong>Summer</strong> Management Season Concludes<strong>Prairie</strong> Operations Manager Richard Datemareported that the summer work crew had completedherbicide treatment of sericea lespedezaon all MPF prairies. For more than two months,the team of Beth Meyers and Jeremy Watkinsarrived at various MPF prairies and a few partners’properties by dawn to assist Datema withland management activities before the summerheat reached dangerous levels. In addition to sericeatreatments, the summer crew, Datema andcontractors sprayed other invasive species, clearedbrush and finished clearing nearly all trees fromCoyne and Penn-Sylvania prairies to prepare thesite to be fenced this fall. In October, MPF LandManagement Chairman Stan Parrish will overseethe movement of a small number of longhorncattle from Schwartz <strong>Prairie</strong> to the 320-acreCoyne and Penn-Sylvania unit. MPF owns 240acres of the property and manages the remaining80 acres between Coyne and Penn-Sylvaniain partnership with landowner Julian Snadon.MPF’s summer work crew for <strong>2007</strong> was fundedby Wildlife Forever, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department ofConservation (MDC) and the USDA’s GrazingLands Conservation Initiative.

gather at Friendly <strong>Prairie</strong>During the meeting, MPF received a checkfor more than $16,000 from Elizabeth Hamiltonof Hamilton’s Native Outpost seed company.Hamilton’s collects seed from many MPFprairies, and the funds are MPF’s share from the2006 seed harvest. Parrish and Datema noted thatthe seed revenue exceeds what MPF received inthe past when cutting and selling prairie hay was acommon management technique. Approximately$11,000 of MPF’s seed revenue came from sitesthat had been planted in the last four years withgrant funds from the National Fish and Wildlife<strong>Foundation</strong>, MDC’s Wildlife Diversity Fund andthe U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-ChickenRecovery UpdateMax Alleger, who leads thestate’s Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Recovery team,reported that MDC hadreceived a new federal grantfrom the U.S. Fish andWildlife Service that willprovide nearly $650,000 overthree years to help improvegrassland bird habitat on propertyin the Grasslands CoalitionFocus Areas. A major portion of the grantfunds will be administered by the <strong>Missouri</strong>Conservation Heritage <strong>Foundation</strong> to encouragepartnerships, matching funds and innovativeon-the-ground delivery. Rick Thom, who wasnamed MPF’s <strong>Prairie</strong> Professional of the Year for2006, recently retired from MDC and has justbecome the executive director of the <strong>Missouri</strong>Conservation Heritage <strong>Foundation</strong>.Permanent Protection andPerpetual ManagementBy the end of September <strong>2007</strong>, MPF will receivemore than $500,000 from nine GrasslandReserve Program easements placed on MPFprairie parcels (such as at Runge <strong>Prairie</strong>; seephoto on page 41). The easements placepermanent restrictions on the properties so thatthey will always be protected.Seed collecting, cutting theprairies for hay after the primarynesting season, and sustainablegrazing are allowable uses of theproperties under the federal programrules. At the summer meeting, theMPF board voted to use the easementfunds to pay off remaining debt and toestablish a prairie management endowment fundwith the Community <strong>Foundation</strong> of the Ozarks.Under the CFO’s Stewardship Ozarks initiative,MPF will be eligible to receive up to $50,000 inmatching endowment funds so that future landmanagement expenses can be fundedby investment income.The next MPF board meetingwill be held at Runge<strong>Prairie</strong> outside Kirksville onSaturday morning, October13. The meeting will startat 9:00 a.m. and end atapproximately 1:00 p.m. Atour of area prairie remnantswill be available for interestedmembers and guests. Overnightcamping will be permitted atRunge <strong>Prairie</strong>. All MPF members arewelcome to attend. For more information,contact Justin Johnson at 573-356-78<strong>28</strong> ormissouriprairie@yahoo.com.carol DavitJustin Johnson is MPF’s executive director.Above, MPF PresidentSteve Mowry, left, andExecutive DirectorJustin Johnson, right,conferred during ameeting break. At left,Max Alleger providedan update on greaterprairie-chicken recoveryefforts to ElizabethHamilton and the rest ofthe meeting attendees,below.paul coxCarol Davit

Public Assistance for Privatemdc photoThe last issue of the Journal provided a primer on governmentassistance available for private prairie conservation.The article (pages 8–10) outlined key programs offeredby the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)—the WildlifeHabitat Incentives Program (WHIP), the Environmental QualityIncentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Reserve Program(CRP). Landowners can learn specifics about these cost-share programsby contacting the USDA Service Center in their county.These centers are home to conservation professionals from thefederal Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and thefederal Farm Service Agency (FSA). Many <strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Conservation (MDC) private land conservationists have officesat Service Centers as well. Any of these professionals can help landownerslearn how to implement USDA programs.In this second part of the public assistance primer, programsavailable from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the <strong>Missouri</strong>Department of Conservation are discussed.Partners for Fish and Wildlife ProgramBy Kelly Srigley WernerBack in the mid-1980s, the U.S. Fishand Wildlife Service (USFWS) wasworking to improve declining waterfowlpopulations with many agenciesand groups in the Midwest by restoringwetland habitat on private lands. By1987, the Partners for Fish and WildlifeProgram (PFW) was born. Now recognizingits 20 th anniversary, the PFW programworks to achieve the full missionof the USFWS to work with partnersto conserve, protect and enhance fish,wildlife, and plants and their habitats forthe continuing benefit of the Americanpeople. In October 2006, Congressunanimously approved and the Presidentsigned the Partners for Fish and WildlifeAct to provide for the restoration,enhancement, and management of habitatson private land through the PFWProgram.What does this mean for prairiein <strong>Missouri</strong>? The USFWS’s <strong>Missouri</strong>Private Lands Office works closelywith partners like the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong><strong>Foundation</strong>, the NRCS, the FSA, MDCand many others to promote the restorationand conservation of historic prairiehabitat on private lands.Native prairies, savannas, glades,and loess hills are all important forproviding nesting and brood-rearinggrassland habitat for migratory birds andyear-round habitat for resident birds likethe greater prairie-chicken and the northernbobwhite, not to mention the myriadother wildlife species that utilize thesehabitats. Using migratory bird plans,Grasslands Coalition Focus Areas, speciesmanagement plans, and the historic<strong>Missouri</strong> prairie locations, the USFWShas developed priority zones for prairiehabitat restoration. This focus allowsthe PFW program to target the needs ofgrassland species including those that arein most need due to population declines.Agricultural producers and otherlandowners who contact the USFWS

<strong>Prairie</strong> ConservationA Beginner’s Guide, Part II of IIBy Kelly Srigley Werner and Max AllegerNoppadol paothong<strong>Prairie</strong> wildlife and landowners alike benefit from federal and state assistance programs. Public funds and expertise can help agriculturalproducers and other landowners maximize native plant diversity on working lands, such as grazing land for cattle, and cost-sharing programscan defray costs of restoring and maintaining prairie habitat for greater prairie-chickens, above.office directly or through MDC staff canreceive on-the-ground technical assistanceand learn about ways to make theirdollars go further on working lands andinvasive species control. The USFWSoffers funding to any landowner whovoluntarily wishes to work on a prairieproject through the PFW Program.Federal dollars can be provided tolandowners to help pay for the cost of<strong>Missouri</strong>-source prairie grass and forbseed mix designed for a specific site andthe wildlife species it may support.Landowners can also use PFWfunds for approved herbicides to eradicatefescue and/or control non-nativeinvasive species, fencing, tree removalfrom prairie landscapes, shrub plantingin appropriate areas, and hiringcontractors to do the work. In return, alandowner must agree to and maintaina habitat project for no less than 10years by signing a PFW agreement,which also contains a management planto help guide a landowner throughimplementation and management of aproject. A USFWS wildlife biologist willbe available throughout the length ofthe agreement to provide any additionalassistance that might be needed.Inherent in the name, the Partnersfor Fish and Wildlife Program relieson the partnerships that work toward acommon goal, in this case the restorationof prairie habitats in northern and southwestern<strong>Missouri</strong>. The program operateson the premise that conservation is ashared responsibility between citizensand government. In <strong>Missouri</strong>, 94% ofthe land is in private ownership, and byengaging willing landowners throughnon-regulatory incentives, a largeamount of that land can be improved forprairie wildlife habitat. For more informationon the PFW Program contactyour local MDC private land servicesbiologist or call 573-234-2132 ext. 112.Kelly Srigley Werner is the <strong>Missouri</strong>Private Lands Program coordinator forthe U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

MDC Assistance for <strong>Missouri</strong> Grassland OwnersBy Max AllegerThe <strong>Missouri</strong> Department ofConservation (MDC) provides technicaland financial assistance to all <strong>Missouri</strong>landowners. In many cases, MDCresponds to their requests by providingthe information necessary to help themmeet their land management objectives.In some instances, MDC staff helpslandowners participate in federal or stateincentive programs aimed at helping rareor declining wildlife species and plantcommunities.Making sense of the restrictions ofthe various incentive and cost-share programscan be daunting. To make mattersworse, landowners’ eligibility for suchprograms may vary depending on thelocation of their property and their managementobjectives. For example, someprograms are available only to farmers,while others target lands not intendedfor agricultural production. And, if landis located within a designated Quail andGrassland Bird Focus Area, a landownermay be eligible to receive higher costsharerates for select practices.Thankfully, MDC Private LandConservationists (PLCs) are availableto assist landowners in every <strong>Missouri</strong>County. PLCs are well informed about awide variety of natural resource managementtopics and have the latest informationabout federal and state incentiveprograms that may be available to helpdefray the cost of implementing a landowner’sgrassland management objectives.In the Spirit of Aldo LeopoldAldo Leopold, a forester and ecologist who worked in Wisconsin in theearly 1900s, had close family and professional ties to <strong>Missouri</strong>. Why is thisimportant? In the world of “wildlifers” he is known as the Father of Wildlife Conservationwhose ideas have been passed on to every contemporary wildlife management biologist. Leopoldhad a keen perception of the land and its conservation through a land ethic that still ringstrue. The PFW program employs many of Aldo Leopold’s principles to help connect <strong>Missouri</strong>landowners to their land.Leopold spent considerable time in <strong>Missouri</strong> conducting wildlife surveys in the late 1920s.The results of the surveys indicated that <strong>Missouri</strong> wildlife was in trouble; in fact, he expressedconcern about the decline of habitat for northern bobwhite and greater prairie-chickens dueto the surge in agriculture and the plowing of prairies. Leopold explained “We will have noconservation worthy of the name until food and cover for wildlife is deliberately, instead ofaccidentally, provided for, until abundant wildlife is the mark of the best rather than the worstPhotos by Kelly Srigley wernerFar left, native grasses andforbs now dominate thelandscape on this privateland in northeastern <strong>Missouri</strong>.At left is a private nativegrassland planting, whichis now benefitting northernbobwhite, bobolinks, grasshoppersparrows, andgreater prairie-chickens.

MDC provides funds for landownerswho want to improve habitats ontheir property. Although MDC fundsare far less than those available throughUSDA programs, they can be simplerto tap into for landowners with highlyfocused land management objectives.MDC funds are delivered via the MDCLandowner Assistance Program. Therulebook for this program is called theLandowner Incentive Docket. Thedocket describes available programsalong with the payment rates, rulesand requirements for each. Althoughthe docket includes practices aimed ataddressing the full range of resourceissues faced by <strong>Missouri</strong> landowners, theremainder of this article highlights justthose that are most commonly appliedto restore native prairie remnants, orimprove the habitat value of other privatelyowned grasslands.Before delving into individual practices,let me point out that landownerrequests for MDC private land fundsalmost always outstrip availability,which often occurs very early within afiscal year. The availability of the practicesdescribed below, as well as thecost-share rates for some, may also varyamong MDC administrative regionsacross the state. There are a couple offarming.” The USFWS private lands program follows Leopold’s premise that for conservation to besuccessful it needs to be practiced on private land where wildlife can have large landscapes to thriverather than being squeezed onto small publicly managed tracts, and the role of government agencies isto help with demonstration, research and public outreach.Leopold wanted conservation to be a focus in <strong>Missouri</strong>. Back in his day, he hoped that <strong>Missouri</strong> wouldnever become industrialized in mind and spirit. <strong>Missouri</strong>ans have proven that conservation is important asevidenced in the conservation sales tax and the parks and soils tax. However, more can be done.In this fast-paced world we live in with the Internet, video games, iPods and cell phones, it is moreimportant than ever to stay in touch with the land and teach children about the wonders of our naturalworld—through a day fishing, hunting, observing prairie-chickens on a lek or walking through a prairie.Nearly 70 years since Leopold’s surveys, the prairie conservation community remains concerned aboutprairie-chickens but now many other birds have been added to the list, including common species likethe eastern meadowlark and dickcissel. Leopold said “Conservation is a state of harmony between menand land. The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: ‘What good is it?’ Ifthe land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not.” TheUSFWS can help landowners connect with every part of their land and keep common species commonthrough the PFW program.Kelly Srigley WernerFor more on Aldo Leopold, read A Sand County Almanac. For more information on declining bird speciesvisit http://www.audubon.org/bird/stateofthebirds/CBID/index.php.important rules of thumb to considerabout these programs:• MDC cost-share funds may be used incombination with federal funds fromthe USFWS or the USDA, but thereare some exceptions, which PLCs canexplain. However, a landowner cannotreceive funds from any combination ofsources in ways that pay for the samework more than once. Landowners cansometimes reduce the out-of-pocketcosts of implementing conservationpractices by counting their labor aspart of their required match.• None of the following practices maybe applied to lands enrolled in CRPunless: 1) the land is not eligible forUSDA mid-contract managementcost-share, 2) at least three yearsremain on the CRP contract, and3) the land is located in a Quail andGrassland Bird Focus Area.As you will read below, the detailscan quickly become confusing, so consultationwith your local PLC is likelyyour best next step after reading aboutthe practices. PCLs will be better ableto assist you if you begin with a gooddescription of the problem(s) you’retrying to overcome or the managementobjectives you have for your land. Oftentimes, a PLC will ask for an opportunityto walk the land with you to betterunderstand your vision for the propertybefore talking about specific incentiveor cost-share programs or practices. Youcan contact your local PLC by callingyour nearest MDC office or by loggingonto http://www.mdc.mo.gov/landown/contacts/.

MDC PhotosAssistance from MDC allowed this woody fencerow, at left, to be removed. A year later, at right, the formerly dissected private grassland isunited, providing improved habitat for ground-nesting birds and other prairie wildlife.Grassland Management Practices fromMDC’s Private Land Incentive Docket:» Landowners can reduce the cost of applying a numberof different early successional management tools to maintainand improve their grassland resources. These practices maybe applied on grasslands or idle areas where the reduction ofundesirable plants and plant residues will improve habitat conditionsor strengthen the native plant community.Keep in mind that participation may mean that grazing orhaying may only be allowed to meet the objectives prescribedby a management plan, and that participants agree to followan approved management plan and maintain the practice for atleast 10 years.» Mechanical disturbance, such as light disking, may bethe best tool to set back vegetative succession in some circumstances.This practice pays $15/acre for mechanical disturbanceup to a maximum of $600/landowner/year. Payment is limitedto once every three years on the same acres.All disking or other soil disturbance must be done oncontours and in strips to minimize soil erosion. Mowing is notan approved practice, and participants must observe a conservationplan prepared by USDA or MDC staff that addresseshighly erodible lands and noxious weed control restrictions. Toavoid disturbing ground-nesting bird species, mechanical disturbanceis not allowed from May 1 through July 15.» Herbicide suppression is used to create vegetative diversityand set back some herbaceous communities. Cooperatorsreceive $10/acre for herbicide application up to a maximum of$1,000/landowner/year.» Woody cover control is used when grasslands, old fieldsor prairies have become overgrown with woody vegetation.This practice can be applied with hand labor or mechanically,with dozers, clippers or similar equipment. Stumps, other thancedar, must be treated with an approved herbicide to preventresprouting. Fallen trees and brush may be left as it lies, piledinto brush piles or removed for firewood. Operations within50' of streams are limited to chain sawing, and debris mustnot be placed in stream channels. The least destructive removalmethod will be used on native plant communities.The cost share is determined by the basal area removed,and will be paid according to the table below, not to exceed atotal payment of $3,750/project/landowner/year. These ratesmay be increased in some Quail and Grassland Bird FocusAreas.Component Chainsaw & Herbicide Mechanical(Clipper or Dozer)Light (20–30BA or$50/acre$65/acreup to 199 trees per acre)Medium (30–40 BA or $65/acre$105/acre200 to 400 trees per acre)Heavy (>40 BA or more $82.50/acre$265/acrethan 400 trees per acre)Loess Hills $337.50/acre N/ABA = basal area» MDC provides financial assistance to construct fencingthat excludes livestock to protect sensitive natural communitiesand attain specific resource management objectives.Cooperators receive no more than $0.25/ft. for electric fencesor $0.75/ft. for conventional fences (gates not included). Totallandowner payment for this practice cannot exceed $7,000/landowner/year. All fences are constructed according to NRCSspecifications, and must be maintained for a minimum of 10years following installation. This practice cannot be used toconstruct property boundary fences or fences along publicroadways unless woody removal is necessary for prairie landscapemanagement. No property boundary fence shall be constructedwithout the consent of all adjoining landowners.» Herbaceous vegetation control helps offset the costs associatedwith removing or reducing undesirable herbaceous veg-10

etation. This practice may be applied to any plant communitywhere non-native herbaceous species limit site restoration ormaintenance potential. This practice can be used in combinationwith burning, haying and grazing to achieve the desiredplant community, which must be maintained as described in anatural resource management plan for a minimum of 10 yearsafter treatment.For grassland conversion practices, payment is authorizedat $22.50/acre/application or a total of $45.00/acre. The totallandowner payment shall not exceed $2,250.00/landowner/year. In some cases, undesirable monocultures can be convertedby transitioning through a period of annual crop production.However, the intent of the practice is not to bring marginallands into agricultural production. Annually tilled lands arenot eligible to receive cost-share assistance for mechanical control.Eligible lands must currently contain a predominance ofundesirable grass species as determined by the MDC resourceplanner.» Herbaceous vegetation establishment helps offset thecost of establishing wildlife-friendly legumes and perennialcool- or warm-season grasses, or native grasses or native forbsto enhance wildlife habitat, improve grazing land diversity,improve water quality or reduce sedimentation.Native warm-season grasses, legumes, and forb seed mustbe purchased from vendors that provide <strong>Missouri</strong>-sourceidentified and <strong>Missouri</strong>-origin seed. PLCs can provide a listof approved vendors, or you can review the <strong>2007</strong> Spring SeedDirectory at http://www.moseed.org/.Cooperators using this practice agree to follow an approvedwildlife or grazing management plan that meets NRCS specificationsand maintains the established vegetation in a wildlifefriendlymanner for a minimum of 10 years. Grazing or hayingis allowed only to meet objectives prescribed by a wildlife managementplan. Cost-share is authorized for fertilizer and limeapplications based on soil test results. Cooperators receive 75%of the actual cost of establishment not to exceed $225/acre and$5,625/landowner/year.» The prescribed burning practice may provide payment forpreparing burn plans, installing fire breaks and implementingone prescribed burn on lands where fire may be safely used toreach specific management objectives.Cooperators personally conducting prescribed burns andreceiving MDC financial assistance must attend an approvedprescribed burn workshop and follow a prescribed burn planprepared to MDC standards. Cooperators utilizing contractorsare not required to attend training. Burn plans developed bycooperating agency staff must meet NRCS or MDC standards.Cooperators will follow an approved management plan for aminimum of five years following the cost-shared burn.Flat rate payment for prescribed burning is determinedby the land cover being burned. For grasslands, the paymentfor the first 15 acres is limited to a maximum of $25/acre.Additional payments are authorized for firebreak constructionand burn plan preparation. Acres beyond 15 are eligible for amaximum of $15/acre up to a maximum of $2,500.» The deferred haying and grazing practice pays landownersa maximum of $27.50/acre/year to defer haying or grazing onselected lands to allow for the establishment or resting of wildlife-friendlylegumes, perennial cool- or warm-season nativegrasses or forbs to enhance wildlife habitat and improve grazingland diversity.This practice may be used on native prairies and haymeadows and pastures where wildlife management is a primaryobjective. Deferment payments may be made to cooperatorsusing a rotational grazing system to establish a refugepaddock(s) that is idled to create nesting cover for grasslandbirds.A cooperator may receive a maximum of $3,500/year andis limited to two years of participation. A landowner mustagree to follow an approved grazing management plan andmaintain the enrolled acres in a wildlife-friendly manner asdetermined by the MDC planner for a minimum of 10 years.Max Alleger is a private land conservationistwith the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservationand a technical advisor to the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>.Landowners can receive funding from MDC to offsetthe costs of prescribed burns.MDC Photo11

Innovation in BloomMy Month as a Kinship Conservation Fellowby Justin JohnsonThis past June and July I was challenged, encouraged andinspired by conservation leaders from around the world.As one of 18 Kinship Conservation Fellows, I traveled toBellingham, Washington, for five weeks of classroom instructionby brilliant faculty and guest speakers, field trips to theawe-inspiring Olympic Peninsula and late night discussionswith amazing colleagues. In short, my eyes have been openedand there is no going back.The Kinship Conservation Fellows program is funded bymembers of the Searle family, who sold their pharmaceuticalcompany to Monsanto in 1985. The program started in 2001in association with the Property and Environment ResearchCenter in Bozeman, Montana. The <strong>2007</strong> class was the firstto be hosted at Western Washington University and led by anew program director, Jim Tolisano of the University of NewMexico. The official Kinship mission statement is,“To develop a community of leadersdedicated to applying market-basedprinciples to environmental issues,”but in reality, the program gets to something more basic andpotentially more powerful than that. Using a mix of economictheory, practical application and institutional professionalism,the Kinship method seeks to bring the conservation communityand the corporate world together, and in the process, helpeach side learn from one another.Conservation is Good for BusinessUsing resources sustainably, reducing waste and saving moneyare all good for the corporate bottom line, but until recently,the suggestions of many conservation groups were ignored bythe business community.Today, seemingly every other television commercial toutsa new conservation consciousness: Toyota and other makers offuel-efficient vehicles are grabbing market share, and Wal-Marthas quickly figured out that less packaging means less weightand therefore lower shipping costs, higher stocking densitiesand more profit. Businesses like these aren’t going to stoptrying to get people to buy more and more of their products,but if waste can be reduced or the impacts of waste can bemitigated, all the better.Charlie Avis, one of the Kinship participants and anenvironmental program manager for several World WildlifeFund (WWF) projects throughout Europe, put it simply: “Foryears we’ve viewed those in business as our opponents, but inreality, if we can show them a way to make money that helpsthe planet, they’ll go for it. We need to go to the people whohave the money and get it.” Avis noted that the WWF officein the Netherlands was particularly well funded, but it pales incomparison to even the marketing budget of the Dutch brewerHeineken.Large corporations make charitable contributions throughtheir foundations, but it is the potential of the revenue-side ofthe house that is largely untapped. In the not-so-distant future,huge money could be made by taking sustainable resources,such as prairie grasses, and brewing them into cellulosicethanol. (See page 26 of this past winter’s Journal for moreinformation.) There could be a major role for <strong>Missouri</strong>-basedmultinational companies Anheuser-Busch and Monsanto,and of course private landowners in <strong>Missouri</strong>, to explore thisopportunity.Ruth Norris, a grant manager for the Skoll <strong>Foundation</strong> anda visiting lecturer for the Kinship program, noted that, asidefrom corporations, even charitable foundations are approachedincorrectly by most non-profit groups. “Think of a foundationas having two pockets,” Norris said. “In one pocket you havethe 5% interest off the corpus that these large foundations haveto give away each year, and that is the side every non-profitgroup approaches. But in the other pocket you have all the realmoney, and that has to be invested in something.” Norris saysthat a lot of those large foundations can’t or won’t invest inthings like oil and gas stocks that conflict with their mission, soif conservation groups can design “program-related investment”opportunities that produce a safe return, the funding potentialis nearly unlimited. The key is to show businesses how doingthings naturally can either create profit or reduce expenses.Premium-priced goods—anything from lumber to beef towine—that are sustainably produced and marketed as such havethe potential to make landowners and producers more profit.Protecting and managing a watershed to improve water qualitycould be more efficient for a community than raising taxes tobuild a new water treatment plant. This is a rapidly emergingfield that is more developed in areas where basic resources, suchas water, are more scarce and development pressures are higherthan in <strong>Missouri</strong>.Corporations Produce Results, Shouldn’t Non-Profits?As much as businesses can benefit from thinking like conservationists,the non-profit sector needs to learn from corporations.Another Kinship speaker, Francis Pandolfi, is a businessconsultant who advised program participants to sharpen their12

organizations by identifying a competitiveadvantage. “You must be able to tell otherswhat you do in a very simple way,” Pandolfisaid. “Even more important, you must be ableto differentiate your organization from all theothers. Why should peoplesupport you rather than the other guy?”Pandolfi also defined marketing asdetermining what people want and giving itto them. This is instructive for the <strong>Missouri</strong><strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF). A recent poll revealed that morethan 70 percent of landowners in <strong>Missouri</strong>’s <strong>Prairie</strong> ChickenFocus Areas had not seen a prairie-chicken in more than fiveyears. That same poll showed that landowners felt it was moreimportant to have quail and grassland birds on their propertythan prairie-chickens, which makes sense because many havenever seen a prairie-chicken. At the same time, prairie-chickensrated higher than deer. By restoring healthy grasslands, MPFcan increase the numbers of common prairie birds, such asquail, meadowlarks and field sparrows that are familiar to peopleand also bring back prairie-chicken populations so that morepeople will see them and appreciate them.Perhaps the most challenging concept presented duringthe Kinship discussions about business was the issue ofperformance. Generally most non-profits do a terrible jobreporting results. The most common measures of success inconservation projects are the number of dollars spent and theacres affected. While MPF gets high marks for spending moneyefficiently and bringing multiple sources of funding to projects,in the future, MPF needs to work with other partners such asAudubon Society of <strong>Missouri</strong> to monitor wildlife’s response toall the dollars being spent to improve acres of habitat.Moving Forward with a New PerspectiveThe Kinship program also provided me with a perspective on amuch smaller scale of business—the community level. ProgramDirector Tolisano and program participant Torjia Sahr Karimuof Sierra Leone have worked together on chimpanzee conservationin West Africa. Both said that frequently, the concerns ofthe local people are ignored. “The scientists come into the communityand clearly care only about the chimpanzees,” Karimusaid. “They dress it up in a smokescreen called conservation,but the people can tell.” Several other program participants,such as Jean-Marie Benishay of the Democratic Republic ofCongo and Adam Hannuksela who works in Mexico, spokeof the devastating effects of natural resource exploitation byAttending the opening Kinship dinner on June22 are, from left, MPF’s Justin Johnson and otherfellows Torjia Sahr Karimu of the ConservationSociety of Sierra Leone, Jean-Marie Benishayof the Democratic Republic of Congo’s BonoboConservation Initiative and Johnjoe Cantos of theWorld Wildlife Fund in the Philippines.By the end of the program, the Kinship fellowshad become great friends and had gaineda greater understanding about the future ofconservation. From left are Julie Ziff Sint ofNew York City’s Tri-State Biodiesel, Zo LalainaRandriarimalala of Conservation Internationalin Madagascar, MPF’s Justin Johnson, and SteveParrett of the Oregon Water Trust.local people who have few options. Program instructor NejemRaheem put it this way, “When the difference between feedingyour family and starving to death is determined by how manyhours you can work and how many trees you can cut down, itis hard to think about conservation.”There is hope for local people in the developing world, andthat hope needs to inform MPF’s work in rural <strong>Missouri</strong>. Inmany African countries, tourism and non-timber forest products,such as bee’s wax and honey, give residents alternatives tocutting down the trees. In Belize, Kinship participant JonathanLabozzetta is working to help local people sell the lobster theycatch at a premium price to local tourist markets rather thansell them cheaply to commercial export buyers. If MPF wantsprivate landowners to conserve remnant prairie and restore formerprairies to useful grassland habitat, we have to ask what thelandowners want and what they need to make a living.On December 1 at the <strong>Missouri</strong> Livestock Symposium inKirksville, representatives from MPF, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Conservation, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and theUniversity of <strong>Missouri</strong> Extension Service will speak to privatelandowners about emerging business opportunities that mix wellwith conservation. By keeping the questions raised during theKinship program in mind, the conservation world and the businessworld can begin to collaborate and profit from one another.As Chad Brealey, a 2002 Kinship fellow who works to protectsalmon habitat in British Columbia said, “Conservation is aboutlooking forward, innovating, adapting and creating the changesyou want to see. If you don’t change behaviors, you’ll just becaught in a cycle of restoration, degradation and restoration.”In the next few Journal issues, I will discuss new toolsfor conservation, such as carbon credits, transferable developmentrights and payments for ecosystem services, that have thepotential to conserve <strong>Missouri</strong>’s prairie in a viable, long-termway. I welcome any comments at missouriprairie@yahoo.comor 573-356-78<strong>28</strong>.Justin Johnson is the executive directorof the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>.

Grasslands of Cuivre River State ParkMost of the 6,400 acres of Cuivre River StatePark is oak woodland, but the park’s four prairieunits add immense biological value. Even thoughthese four tracts cover only 100 acres, manyprairie species wouldn’t exist in the park withoutthese grassland jewels.Cuivre River State Park had its origins duringthe depression of the mid-1930s, but recognitionof the park’s prairie resource didn’t occur untilthe mid-1970s. In 1976 Sac <strong>Prairie</strong> was burnedfor the first time in what was the first ecologicallybased prescribed burn ever conducted in a<strong>Missouri</strong> state park. Sac <strong>Prairie</strong> covers only fiveacres, yet it supports more than 80 species ofprairie plants including prairie blazing star, roughblazing star, cream wild indigo, rosinweed, prairiedock, prairie rose, ragged orchid (Platantheralacera) and rattlesnake master.Of the park’s four prairie units, Sac <strong>Prairie</strong> isthe smallest, but still has good diversity and thelongest management history. Sherwood <strong>Prairie</strong> isthe largest, and includes more than 50 grasslandacres within a savanna/woodland matrix coveringa total of 150 acres. The entire management unitsupports more than 240 plant species. Besides thecharacteristic prairie plants already listed, this sitealso supports showy goldenrod (Solidago speciosa),white lettuce (Prenanthes aspera), willow-leavedaster (Aster praealtus), prairie sedge (formerly astate-listed species), prairie willow (Salix humilis),the park’s only stand of compass plant, anda state-listed species of conservation concern—eared or auriculate false foxglove (Agalinis auriculata).Dry Branch <strong>Prairie</strong> has 25 acres of grasslandand savanna, which also supports a population ofthe foxglove. Northwoods <strong>Prairie</strong>’s ten acres mayhave the least overall diversity, but still support animportant flora that includes prairie sedge, prairiewillow, and an impressive display of butterflymilkweed. Another state-listed species, easternblazing star (Liatris scariosa), occurs in one of severalother small scattered grassland tracts.Cuivre River’s prairies provide importanthabitat for many animals too. Birds that are frequentlyfound in and around the park’s prairiesinclude the northern bobwhite, field sparrow,blue-winged warbler, common yellowthroat,white-eyed vireo, eastern towhee, yellow-breastedchat, rose-breasted grosbeak and summer tanager.Many characteristic prairie insects are alsoknown from Cuivre’s prairies, ranging from antcolonies below the ground to a diverse assemblageof pollinators flying above it. Surveys have documented81 kinds of butterflies using the prairies,including some notable ones like coral hair-Bruce SchuetteTall green milkweed(Asclepias hirtella),at left, and noddingladies’ tresses orchid(Spiranthes cernua),below, are two of themany plant species ofCuivre River State Park’sgrasslands. The milkweedblooms from latespring to summer andthe orchid from midsummerto fall.CaptionsBruce Schuette15

St. Louis Area Urban <strong>Prairie</strong>sBruce SchuetteBruce SchuettePollinators, such as thisbee above, thrive on thenectar provided by adiversity of wildflowersgrowing on CuivreRiver’s many acres ofprairie and vast tracts ofsavanna and woodland,at right.streaks, (Harkencleuus titus), Edward’s hairstreaks(Satyrium edwardsii), and the golden byssus skipper(Probleme byssus kunskata).Since 1976 all the park prairies have beenincluded in the prescribed burn program. Someclearing of invading woody brush and trees fromthe prairies has also been necessary because ofthe long period of time that fire was absent fromthe system. In addition, prescribed fires burninginto the woods are restoring the savanna edge andopen oak woodland that were so prominent whenthis region was first settled.Small limestone glades are also scatteredamong the southerly facing hillsides throughoutthe park. To greater or lesser degrees these naturalcommunities may in fact also be considerednative grasslands in their own right—they caneasily be seen as dry prairies with shallow soilsover bedrock and frequent exposures of bedrockon the surface. Glades are extremely rare thisfar north in <strong>Missouri</strong>, with many species at thenorthernmost extreme of their global distribution.Prescribed burns and removal of highlyinvasive eastern red cedar trees are also insuringthe survival of these rare and diverse little grasslandgems.Savannas are basically prairies with ascattering of tree cover. Even the oak woodlandshave a lot in common with grasslands, includingthe prominence of grasses, sedges and shadeintolerantwildflowers in the groundcoverlayer. Species like leadplant, purple milkweed,Carolina rose, cream wild indigo, slenderlespedeza (Lespedeza virginica), American feverfew(Parthenium integrifolium), wild ryes and othersprovide testimony to woodland affinities with ourgrasslands.In 1997 the Lincoln Hills Natural Area wasestablished in the park to preserve the full rangeof terrestrial natural communities found in theLincoln Hills ecological region. Included withinthe 1,872-acre natural area are caves, sinkholeponds, limestone glades, bluffs, bottomlandforest, upland woodlands and prairie. Sac,Sherwood and Dry Branch <strong>Prairie</strong>s are all part ofthe natural area, demonstrating the importance ofthese native grasslands in protecting the region’sbiodiversity and natural history.Bruce Schuette, Cuivre River State Parknaturalist and MPF board memberLocation/Directions: Cuivre River State Park islocated 3 miles east of Troy off of Highway 47 incentral Lincoln County. For more information, contactBruce Schuette at the park at 636-5<strong>28</strong>-7247.16

CaptionScott WoodburyShaw Nature Reserve’s Experimental<strong>Prairie</strong> and <strong>Prairie</strong> GardensShaw Nature Reserve in Gray Summit, <strong>Missouri</strong>,a satellite facility of the <strong>Missouri</strong> BotanicalGarden, is a showcase of natural communityrestoration and construction. Included in its2,400 acres are more than 10 miles of hikingtrails through the Shaw Bottomland Forest StateNatural Area, glades, woodlands, constructedwetlands and prairie areas, and a wildflower garden.Shaw Nature Reserve (SNR) also is a leaderin environmental education and native plantlandscaping.Approximately 250 acres of constructed prairiehabitat at SNR began with 76 acres plantedin 1980, thanks to financial assistance from the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>. From its humblebeginnings as a low-diversity planting of fourgrasses and four forbs, this planting graduallygained additional species through spontaneouscolonization, transplanting and overseeding.It has also become excellent habitat for prairiefauna.The original 76-acre planting is now hometo about 200 plant species. Some of these areexotics, including noxious species such as sericealespedeza and the sweet clovers, these being controlledthrough annual vigilance and judicious useof mowing and herbicide. Annual or biennial fireis an important part of the overall management ofthe SNR prairie complex and all adjacent woodlands.Approximately half of the prairie acreage isburned each winter, preferably when the groundis frozen or at least, wet and cold, thus protectingthe winter hiding places of many prairie insects.Additional plantings have continued throughthe years, with the latest five-acre addition sowedin the winter of <strong>2007</strong> in an area sporting a teepeeand a sod house, which are central to the reserve’seven-numbered years’ celebration of <strong>Prairie</strong> Day.Thanks to the additional plantings and the variedsoil conditions and hydrology of the landscape,total prairie plant species diversity now approaches300 species, including those in the wetlandscomplex.James TragerShooting stars bloomin spring on a recentlyestablished prairieplanting near theWhitmire WildflowerGarden at Shaw NatureReserve, top, and acicada killer wasp(Sphecius speciosus) visitsa rattlesnake masterflower head on theexperimental prairie atthe reserve.17

St. Louis Area Urban <strong>Prairie</strong>sThe acreage nowbrimming with prairiespecies at Shaw NatureReserve (bottom photo)was formerly a fescuepasture dotted witheastern red cedar, below.Thanks to decades ofwork by MPF boardmember Bill Davit,reserve biologist Dr.James Trager, and manyother former and currentstaff and volunteers, thereserve’s grasslands aretoday rich and diverse.With plants in bloom from the first appearancein spring of lousewort, cream indigo, shootingstar and Indian paintbrush to the grand finaleof asters, goldenrods and gentians in fall, theflora of the SNR is a joy to behold and servesas a great learning resource for St. Louis areaplant enthusiasts. It is also home to a diversityof prairie animal life, including such highlightsas healthy breeding populations of prairie kingsnakes,northern yellowthroats and Henslow’ssparrows in the more open areas, and indigo buntings,orchard orioles and yellow-breasted chatsin brushier parts andwooded edges. Plansare afoot to furtherenhance the diversityof the SNR prairies,including developmentof sufficientpopulations of prairieand arrow-leavedviolets to supportan introduction of the threatened regal fritillarybutterfly, which was once native to the St. Louisregion.Finally, and rather more forb-rich but neverthelessever less distinct ecologically from thereserve’s original prairie constructions, are thespacious and showy prairie plantings associatedwith the Whitmire Wildflower Garden. Startingas a one-acre prairie garden, SNR’s horticulturestaff has gradually expanded prairie plantingsonto the gently rolling acreage south of the moreformal parts of the garden. In the garden itself,prairie plants are labeled, as are several hundredother <strong>Missouri</strong> native plant species.Dr. James Trager, biologist,Shaw Nature ReserveLocation: Shaw Nature Reserve is located at theintersection of Interstate 44 and Highway 100at Gray Summit. For more information,visit www.shawnature.org or call 636-451-3512.Bill davitScott WoodburyThe Litzsinger RoadEcology Center <strong>Prairie</strong>The Litzsinger Road Ecology Center (LREC) is a34.5-acre environmental education center managedby the <strong>Missouri</strong> Botanical Garden and islocated in St. Louis County. The LREC is notopen to the public. Primarily the facilities andgrounds are used for K-12 student field studyand ecological research. Students in St. Louis areaschools visit the site multiple times throughoutthe year to learn about restored prairie, bottomlandforest, and creek ecosystems throughscientific inquiry and by helping with ecologicalrestoration. The LREC averages several thousandstudent visits per year. The LREC also offers fiveresearch grants each year to undergraduate, graduateand faculty researchers to conduct ecologicalresearch on site. Current research projects includethe effects of invasive plant species on nativeplant species pollination, invasion patterns of the18

Japanese pavement ant, movement of rattlesnakemaster pollinators, structure and organization ofurban butterfly communities, and interactionsbetween wild senna and herbivores.Restoration efforts began on site in 1989with the restoration of 10 acres of mesic to wetmesic prairie. The original restoration effortincluded grass seeds from a nursery near KansasCity and locally collected forb seeds. <strong>Prairie</strong> restorationhas continued with another two acresof prairie restored between 1999 and <strong>2007</strong>.The seeds for this restoration were all collectedwithin 100 miles of the LREC. The big bluestemwas collected from Calvary Cemetery andis now being collected from the LREC restorationto contribute to the restoration of CalvaryCemetery’s prairie. The prairie restorations haveapproximately 216 plant species, of which 179are native to <strong>Missouri</strong>. Characteristic plants ofwet mesic prairie that are present at the LRECinclude big bluestem, prairie cord grass, switchgrass, sweet coneflower, foxglove beardtongue,rattlesnake master, bottle gentian, ragged orchid,and bunchflower.The 14 acres of bottomland forest at theLREC are in the process of restoration. Becauseof the proximity to Deer Creek, an urban stream,the forest often experiences flash flooding, sedimentdeposition, and the invasive plant speciesoutbreaks that follow. The creek also bringswater-loving wildlife to the area, however. Nearly100 species of birds, 18 species of mammals, 10species of amphibians, 23 species of reptiles, andmany species of invertebrates have been recordedat the LREC.Malinda W. Slagle, restoration ecologist,Litzsinger Road Ecology CenterThe LREC is not open to the public, but if you areinterested in conducting a K-12 field study or ecologicalresearch at the LREC, please contact MarthaSchermann at martha.schermann@mobot.org or314-442-6717.Canada wild rye grass,top, catches the lightat the Litzsinger RoadEcology Center prairie.Hundreds of studentsvisit the LREC prairieevery year, learningabout an ecosystem thatonce covered 17% ofSt. Louis County.CaptionBilL Davit Photos Heather Wells-sweeney19

St. Louis Area Urban <strong>Prairie</strong>sCarol DavitVisitors to the KennedyWoods Savanna,above, can enjoy thestately oaks, grassesand wildflowers fromwalking and bikingpaths through the area.Another grassland atForest Park, at right,is the Deer Lake WetSavanna Complex,pictured here withseveral aster species inbloom.Forest Park GrasslandsTwo areas in the City of St. Louis’s Forest Parkhave been transformed in the last ten years withprairie and savanna vegetation. Established firstwas the Kennedy Woods Savanna, near the ArtMuseum and between Kennedy Woods andSkinker Boulevard. Inspired to create a grasslandarea at the park after a visit to <strong>Prairie</strong> State Parkin 1996, <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) andKennedy Woods Advisory Group member KenCohen pitched the idea at an MPF board meeting.The board responded with $1,500 to begin asavanna project among the stately oaks growingalong the edge of Kennedy Woods.Gary Schimmelpfenig, project manager withDJM Ecoscapes, Restoration and Management,produced a plan for the site and organized volunteerprairie seed collecting for the project in1998 at Shaw Nature Reserve in Gray Summit,<strong>Missouri</strong>, and Gordon Moore <strong>Prairie</strong> in EastAlton, Illinois. The area was treated with glyphosate(generic Round-Up) that fall. In May 1999,22 volunteers hand-scattered the seed (about 15pounds of shade mix and 75 pounds of sun mix).In what previously was just another area ofmowed lawn is today a constructed savanna withGary Schimmelpfeniglush wildflowers and grasses growing beneathmammoth oaks. It is alive with insects and birds,and people experiencing a landscape original tothe Midwest.The second area in Forest Park now distinguishedby prairie vegetation is the DeerLake Wet Savanna Complex. Located at theeastern end of Forest Park in the Deer Lake andSteinberg areas, the complex covers approximately15 acres and features plants native to prairie,savanna, and bottomland forest. Included in thecomplex is a flowing stream lined with limestoneand simulated limestone bluffs.20

The complex was designed by the landscapearchitectural firm of Oehme, van Sweden andAssociates, Inc. The design included five palettes—differentassemblages of plant species forprairie, savanna and bottomland forest areas—forthe Deer Lake area and eight palettes for theSteinberg area. The plantings were installed byDJM Ecoscapes, Restoration and Management.Before planting, glyphosate was applied toexisting vegetation in September 2002 and thenative seed was installed in February 2003 usinga no-till Truax seed drill. Shade-tolerant specieswere seeded based upon tree shade patterns.Several thousand plugs were also planted includingcommon boneset, rough blazing star, sweetconeflower, swamp milkweed, golden ragwort,and switchgrass, as well as sedges, rushes andwetland emergent plants. Today, the complex isvisually stunning, with drifts of wildflowers andgrasses blooming throughout the growing season.Location: Forest Park is 1,293 acres in the City ofSt. Louis. It is bounded by Oakland Ave./Hwy.40/64 to the south, Skinker Blvd. to the west,Lindell Blvd. to the north and Kingshighway to theeast. For more information, contact Forest ParkForever at 314-367-7275.21

St. Louis Area Urban <strong>Prairie</strong>sJan OberkramerAttending the RogerPryor Memorial <strong>Prairie</strong>Garden dedicationceremony on November11, 2006, are from left,Roger Pryor’s son-in-lawKen Dickenson, Kay Drey,and son Andrew Pryor.Conservationist LeoDrey and Green Centerstaff, volunteers, andfriends also attendedthe ceremony. Beforehis death in 1999,Roger Pryor was thesenior environmentalpolicy director for the<strong>Missouri</strong> Coalition for theEnvironment. For morethan three decades,he worked to protect<strong>Missouri</strong>’s naturalresources.Green Center <strong>Prairie</strong> ProjectsNow six years old, the Roger Pryor Memorial<strong>Prairie</strong> Garden was planted in June of 2001 at theGreen Center in University City. Funds for the<strong>Prairie</strong> Garden were raised by the Green Centerin Roger Pryor’s memory and were matched by agrant from the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>.The garden is a mixture of low-growingprairie grasses and flowering forbs and has pathsthrough the garden. All the plants are local ecotypesfrom within a 100-mile radius of the GreenCenter. These include Warrenton Red littlebluestem from Warren County, <strong>Missouri</strong>, anda lovely blue Canada wild rye from Illinois. Thegarden is a wonderful urban native plant garden,full of plants that bloom throughout the seasonand look great in the winter. Roger Pryor lovedprairies and he would have undoubtedly lovedthis prairie garden. With the help of volunteers,the Green Center maintains the garden by weeding,mowing and burning. A prairie dropseedborder planted around the garden and its pathwayscreates a more formal look.A quarter mile from the Green Center, nextto Brittany Woods School, is the Green Center’shalf-acre prairie. This prairie was planted in 1990by Ed Murray, who was a science teacher at theschool. This prairie contains taller grasses like bigbluestem and Indian grass, white wild indigo, andmany other forbs and grasses. The Green Centerprairies are teaching tools for the science classesand summer camps that the Center offers to studentsthroughout the St. Louis metropolitan area.The Green Center is also a partner in theCalvary Cemetery <strong>Prairie</strong> Restoration Project,along with the Archdiocese of St. Louis CatholicCemeteries, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department ofConservation, The Nature Conservancy and the<strong>Missouri</strong> Botanical Garden. Called the CalvaryCemetery <strong>Prairie</strong> Partnership, these organizationsare working to preserve and restore this valuablenatural and historic resource.The goal of the Calvary Cemetery <strong>Prairie</strong>Restoration Project is to restore a diverse, viableprairie remnant and to integrate this resourceinto the fabric of local and regional life. Given itsAdrian Brownproximity to the graves of influential St. Louisfigures, the prairie at Calvary Cemetery (seebelow) presents a unique opportunity to link thehuman and ecological history of the St. Louisregion. Its value lies not only with its restorationpotential, but in what it uniquely represents: a“last of its kind” place for people in St. Louis toexperience a native prairie ecosystem.Jane Schaefer, MPF member and oneof the founders of the Green Center. Jane hasbeen board chair of The Green Centerfor the past two years and oversees theCenter’s native gardens.Location and contacts: The Green Center islocated at 8025 Blackberry Avenue, UniversityCity. For more information about Green Centerprairie projects, visit www.thegreencenter.org, callthe center at 314-725-8314 or e-mail ExecutiveDirector Susan Mintz at smintz@thegreencenter.org or Restoration Manager Carissa Gigliotti atcgigliotti@thegreencenter.org.Calvary Cemetery <strong>Prairie</strong>Within the 477 acres of historic CalvaryCemetery in north St. Louis are approximately25 acres containing patches of native prairie. Thisis perhaps the last remaining remnant within theHighway 270 corridor of a landscape that oncecovered nearly two-thirds of the city.Calvary Cemetery was formally incorporatedin March 1857, when Archbishop Peter Richard22

Kenrick purchased and dedicated this land to anew cemetery. The existing prairie remnant isnear the grave of St. Louis co-founder AugusteChouteau. Other notable St. Louisans buried atCalvary include Dred Scott, General William T.Sherman, the writers Tennessee Williams andKate Chopin, and Surveyor General AntoineSoulard.“The Archdiocese has agreed to protectand set aside this prairie remnant for the next100 years to allow for the management of thissignificant piece of prairie,” said Msg. RobertMcCarthy, the archdiocese’s cemeteries director.“This is an opportunity to preserve one of thejewels in the St. Louis landscape and include ourlocal community in this collaborative effort tocelebrate and learn from this unique find.”While 130 species of native flowering plantshave been identified in the prairie, the remnantis severely deteriorated, according to Doug Ladd,director of conservation science for the <strong>Missouri</strong>chapter of The Nature Conservancy. Exotic speciesinfestation, encroachment of woody vegetation,fire suppression and past land-use historyhave all taken their toll on the prairie.Members of the Calvary Cemetery <strong>Prairie</strong>Partnership are working to protect, restore andsustain this prairie remnant. In the fall of 2005,native grass seeds were harvested at the site andplanted this past June. The Nature Conservancy,one of the partners in the project, is monitoringprogress of the restoration, and, along withthe <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation, willconduct prescribed burns of the prairie. The<strong>Missouri</strong> Botanical Garden is providing scientificexpertise and the facilities for the cultivation ofnative plants. The Green Center of UniversityCity will lead community outreach and educationprograms and provide leadership in coordinatingcommunity volunteers for conservation activities.Adapted from a January 31, 2006 <strong>Missouri</strong>Botanical Garden press releaseLocation and directions: Calvary Cemetery is locatedat 5239 W. Florissant Avenue, St. Louis. To reachthe cemetery by car from downtown St. Louis,take I-70 west to the W. Florissant exit (Exit 245B).Merge onto W. Florissant and proceed 0.9 milesto the entrance to the cemetery. The cemeterygates are open daily 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Inquireat the cemetery office for directions to the prairie.Cemetery office telephone number: 314-381-1313.Howell <strong>Prairie</strong> at the Weldon Spring SiteIn 2003, the U.S. Department of Energy planted150 acres with native prairie species at WeldonSpring in St. Charles County around a 70-foothighrock-covered radioactive waste repository.Referred to as the “Weldon Spring DisposalCell,” the repository or mound stores wastes createdwhen the area was used in the 1940s, ’50sand ’60s first for producing explosives and laterfor processing uranium ore concentrates.Called Howell <strong>Prairie</strong> in recognition of thelarge presettlement prairie that once existed inthe area (6,400 acres—10 square miles), theconstructed grassland is open to the public fromdawn to dusk and may be viewed from a milelongtrail around the mound, or from atop themound. Also open to the public is a five-acreinterpretive garden composed of prairie plantsand native trees and shrubs, and an interpretivecenter that presents exhibits and information onthe history of the site.In April 2006, the Hamburg Trail, a 10-milerecreational path running through the area, wasdedicated. The trail connects the KATY Trail andBusch Conservation Area and is open to pedestriansand bicyclists.Bill Davit, MPF board member andHowell <strong>Prairie</strong> Council memberLocation and directions: 7295 Highway 94 South,St. Charles, MO 63303. From Hwy. 40/64 or Hwy.70, exit at Hwy. 94 and continue south to just pastHwy. D. Telephone: 636-441-8066.U.S. Dept. of EnergyThe prairie at CalvaryCemetery, lower photo,facing page, is perhapsthe St. Louis area’sonly remaining tract oforiginal prairie withinthe I-270 corridor. Incontrast, the Howell<strong>Prairie</strong> planting, above,is in the very earlystages of construction.The white mound inthe background is thedisposal cell.23

St. Louis Area Urban <strong>Prairie</strong>s<strong>Prairie</strong> Garden Profile:Klondike ParkDo you cringe when you see trees planted in narrowlittle parking lot strips? If so, visit KlondikePark in St. Charles County and cringe no more!Within the park, which formerly was a quarry ona bluff overlooking the <strong>Missouri</strong> River, is a conferencecenter with a “prairie strip” in its parkinglot. The strip is planted with 27 different speciesof native, drought-tolerant prairie plants withinits 18” wide × 290’ long boundaries. The plantsflower from March through November.In addition to providing an attractive, lowmaintenancelandscaping feature, the prairiestrip is frequently admired by gardening groupsand girl scouts who visit the area to learn andpractice their plant identification skills.Klondike Park is on South Highway 94between Defiance and Augusta. For more information,call Gail Schatzler, horticulture supervisorwith St. Charles County Parks and Recreationat 636-949-1830.Gail SchatzlerGail SchatzlerRain GardenProfile:<strong>Missouri</strong>MasterNaturalists’Rain GardenIf you’re driving down SouthMain Street in St. Charles, takea quick detour east to RiversideDrive. You will feast your eyes onthe newly completed <strong>Missouri</strong>Master Naturalists’ drive-by raingarden project on the riverfront.It is just north of, and part of, theLewis and Clark Boathouse andNature Center.Sandwiched between anasphalt parking lot, a cementdriveway, and a rock and steelbuilding, this 30’ × 90’ space wasthe dumping site for leftoverbuilding materials in the past.The site also contained an aluminumflagpole, giant storm drains,electrical conduits and sewagepipes. To top off the harsh growingenvironment, the soil variedfrom moist and wet to cementlikeand sandy.Nevertheless, beginningin March 2006, the ConfluenceChapter of the <strong>Missouri</strong> MasterNaturalists crossed their fingersand rolled up their sleeves intrue “can-do” style, and beganwork on the garden. Over thenext year and a half, in the faceof flash storms, drought andrecent river flooding, membersturned an ugly duckling into ascott barnes Lee Phillionlee phillionMPF member Leslie Limberg introduces teachersto the rain garden, who in a four-day conferencelearned to use the site as a teachingtool for outdoor education and field trips.Before and after: Master Naturalists beganwork on the rain garden in the spring of 2006,and the garden looked great a year later.swan. More than 79 plant species were planted in the garden, including little and bigbluestem grasses, penstemon species, joe pye weed, cord grass and prairie dock.Not only is the garden beautiful to look at, but it effectively filters and slowsrainwater runoff. Now when rainwater pours off the pavement, it travels through therain garden’s new topography, plant life, river rocks, boulders and fallen logs beforeemptying into the garden’s storm drains, which carry the water into the Big Muddy,20 feet away.Leslie Limberg, MPF member and master naturalistIf you know of a rain garden or prairie garden in <strong>Missouri</strong> that you would like to see featured in the Journal, let us know.Contact Editor Carol Davit at davitleahy@earthlink.net or 1311 Moreland Avenue, Jefferson City, MO 65101.24

Visit An MPF <strong>Prairie</strong>•Runge <strong>Prairie</strong><strong>Prairie</strong> Fork ExpansionBruns TractFriendly <strong>Prairie</strong>Drovers <strong>Prairie</strong>Kansas City*•••St. Louis*Schwartz <strong>Prairie</strong>Stilwell <strong>Prairie</strong>Gay Feather <strong>Prairie</strong>Lattner <strong>Prairie</strong>Edgar & RuthDenison <strong>Prairie</strong>Coyne <strong>Prairie</strong>••••• • •*SpringfieldGolden <strong>Prairie</strong>Penn-Sylvania <strong>Prairie</strong>La Petite Gemme <strong>Prairie</strong>ImperviousHigh Density UrbanLow Density UrbanBarren or Sparsely VegetatedCroplandGrassland (native and non-native)Deciduous ForestEvergreen ForestMixed ForestDeciduous Woody/HerbaceousEvergreen Woody/HerbaceousWoody Dominated WetlandHerbaceous Dominated WetlandOpen waterSome late summer and fall prairie highlights: prairie grasses turning gold, purple, brown and red; pink and purple asters,migrating monarch butterflies; dewy spiderwebs; silken milkweed seeds; golden sunflowers; blue sage; and jewel-like gentians.For information about and directions to MPF prairies, contact the MPF office in Columbia at 1-888-843-6739 or 573-442-5842.Map credit: MoRAP, <strong>Missouri</strong> Resource Assessment Partnership25

A Rich Man’s GardenOn a Teacher’s PensionBy Jerry W. BrownAll photos by the authorEvery year since 1994, when I retired fromteaching, I converted an acre or so of oldfield on my property in rural Lincoln Countyto prairie plants. The whole field has been plantednow and comprises close to 12 acres of prairie rangingfrom 13 years to less then a year of development.While a prairie garden—like any garden—is never“done,” I feel a sense of satisfaction at having convertedthis acreage, and I continue to improve andenjoy it. Perhaps my experiences and observationswill help other prairie garden enthusiasts.I came to the planting of prairies as a gardener,not as a botanist or naturalist. My first article forthe <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal was “The Conversionof a Gardener” (<strong>Summer</strong> 1999). It told the storyof how I created my first half-acre prairie gardenand how I was “converted” from revering Englishgardens to honoring American native plant gardens.In my second article, “The Case for <strong>Prairie</strong>Gardens” (<strong>Summer</strong> 2000), I discussed the ecologicand economic reasons for planting prairies,explained how all the goals of serious gardenerscould be achieved by prairie gardening and suggestedthat because of the unique combination ofgrasses and wildflowers, prairie gardens could besuperior to traditional herbaceous borders.Twenty-eight years ago when I built mylittle house here, I started planting an Englishgarden around it with mixed borders of smalltrees, shrubs, evergreens, roses, perennials, andornamental grasses. As the less vigorous of theseplants have died (all the roses), I have replacedthem with prairie grasses and wildflowers. Nowmany of the species from the surrounding prairie26

have seeded themselves into this garden, and Irefuse to weed them out, because they are notweeds. The most invasive plant here is NewEngland aster, and I welcome it. Some of thewildflowers that didn’t do well in the prairie haveflourished after they moved themselves into thegarden. Native plants have a talent for plantingthemselves in exactly the rightplace, and not just in termsof cultural requirements butalso in terms of design. Switchgrass seeded itself right at thecorner of the lily pool where itmakes a perfect accent. Swampaster (Aster puniceus) seededitself along the edge of thedeck where it sends up its largesprays of blue flowers in thefall. Maryland senna seededitself along a path where itsspikes of yellow pea flowers,and later, black seedpods, areperfectly displayed.I have learned that if Ihave a diversity of native plantsin the garden, no single speciescan threaten the others andweeding is unnecessary. WhenI was trying to grow roses,smartweed was an invasiveenemy that required sweatylabor to eliminate. Now when it appears in thegarden, it never gets out of control, and I canaccept it and appreciate its beauty. The Englishgarden is no longer perfectly groomed. In fact, itis scruffy and disheveled, but it makes a perfectwild bird garden. Stocked with a dozen feeders, itis full of birds year-round.In addition to increasing the ground covered,I have tried every year to increase the diversityof species, so there is considerable botanicalinterest here now. As of 2006, 186 prairie specieswere growing here. Of course some of thesenumbered only two or three specimens, butmany numbered in the hundreds.For some species, just addpatience: Last fall I collectedseed from these bottle gentiansand scattered it in wet areas.Five years from now, I’ll startlooking for its closed, bottleshapedblooms.When I first started growing prairie plantsI was surprised how quickly many developedinto big vigorous plants that would bloom thefirst year from seed. But I soon discovered thatsome species such as gentian, shooting star, wildhyacinth, and prairie trout lily were impossiblefor me to grow in the greenhouse. I did learn,however, that they could begrown into flowering plantsby simply scattering the seedand waiting five to eight years.I learned this first from thedowny gentian. After failing togrow this plant in the nursery,I scattered some seed in theprairie. Five years later, discoveringthe brilliant sapphireblue blooms of downy gentiannestled among the grasses wasone of the great joys of prairiegardening. These flowers are ofsuch superb quality you wouldthink they required the greatesteffort and skill to grow, butall they require is patience.Now I am concentratingon establishing rare andmore difficult species. Lastyear I bought three plants ofclosed or bottle gentian from<strong>Missouri</strong> Wildflowers Nursery(Mervin Wallace is a better nurseryman than I).Last fall I collected seed from the plants andscattered it in wet areas. Five years from now,I’ll start looking for its closed, bottle-shaped blueblooms. The pale gentian is well established here,using the same technique from a plant I boughteight years ago. This past spring I found morethan a hundred prairie trout lilies blooming here.These came from a handful of seed I collectedfrom a roadside prairie remnant eight years ago.Shooting stars and wild hyacinths are establishedhere using the same process of collecting andscattering seed and being patient.The prairie has turned me into somethingof a naturalist. During the last four years, I havetourJerry Brown is hostinga tour of his plantedprairie for MPF memberson September 29,from 1:30 to 5:00 p.m.,and a potluck dinnerwill be held from 5:00to 6:00 p.m. Pleasebring a side dish ordessert, your ownbeverage and a lawnchair. Hawk Point isin Lincoln County onstate route 47,11 miles north of theintersection of I-70and 47 at Warrentonand 8 miles west ofthe intersection of61 and 47 at Troy.Directions from thefour-way stop in HawkPoint: West on A 1.4miles to Turkey CreekRoad on right. Northon Turkey Creek 1 mileto Zalabak Road onleft. West on Zalabak0.3 mile to BluestemLane on right. North/west on Bluestem 0.5mile to #175 on right.RSVP to Jerry Brown,P.O. Box 212, HawkPoint, MO 63349,636-338-9298,jwb175@accessus.net.27

Top, sweet coneflowerstems spill into a pathof Jerry Brown’s originalEnglish garden, nowa perfect bird garden.Above, queen-of-theprairieand cordgrass aretwo of the wet prairieplants that Jerry hasestablished around theedge of his small lake.observed and studied <strong>Missouri</strong> birds more thanever before. The more I planted, the more birds Iheard and saw. I have now identified 116 speciesof native birds here in prairie, garden, lake, andwoods.The first grassland birds here were easternmeadowlarks and northern bobwhite. The sweetsong of the meadowlarks is one of the first songsof spring. The quail are here year-round. In thesummer I hear them calling and clucking for theirbrood in the prairie grasses. This winter a covey of17 came to the bird feeders in the garden twice aday. Four years ago dickcissels arrived here withmuch loud singing of their name from perches onthe prairie plants and the electric line above theprairie. In July of that same summer sedge wrensarrived and started their buzzy singing in the prairiegrasses. Both species have returned every yearsince. I have never searched for their nest, but Iassume from their behavior that they are breeding.Four years ago close to eight acres of prairiewere fully developed here. Perhaps that is theminimum grassland required for dickcissel andsedge wren habitat.Once in spring and once in autumn, I caughta glimpse of a LeConte’s sparrow, a rare, furtive,orange-faced bird that quickly disappears downin the tall grass. In winter, swamp, Americantree, and song sparrows are flitting through thetall grasses. In summer they are replaced by fieldand chipping sparrows, common yellowthroatsand indigo buntings. Eight nest boxes on poststhroughout the prairie have been occupied for thelast 10 years by eastern bluebirds and occasionallyby tree swallows. On summer evenings treeand barn swallows are swooping above the prairiefeeding on insects. Late last summer they werejoined for a few days by a large flock of northernrough-winged swallows.Because the prairie is adjacent to garden andwoodland, birds of these habitats use the prairie,not for breeding but for food and shelter. Twosummers ago, I put the binoculars on a commonyellowthroat singing from an indigo bushin the prairie. I was surprised when I saw a maleblue grosbeak in the view. He was such a darkblue that he wasn’t visible to the naked eye. AsI watched, he flew down into the prairie to joinan orange-brown bird, the female blue grosbeak.<strong>28</strong>