Fall 2007: Volume 28, Number 4 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Fall 2007: Volume 28, Number 4 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Fall 2007: Volume 28, Number 4 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

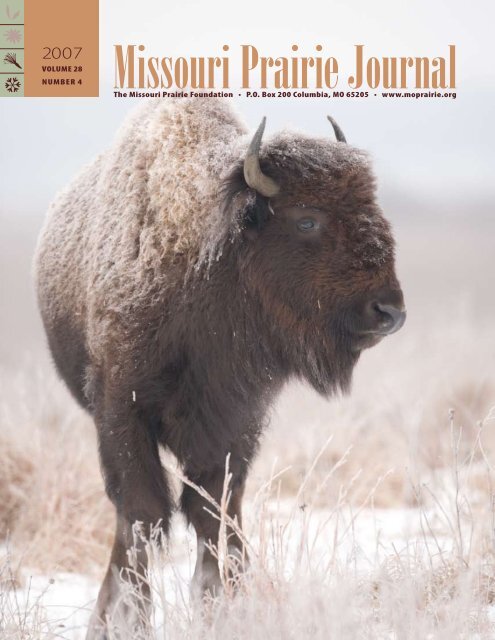

<strong>2007</strong><strong>Volume</strong> <strong>28</strong><strong>Number</strong> 4<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> JournalThe <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> • P.O. Box 200 Columbia, MO 65205 • www.moprairie.org

Message from the PresidentThe <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) needs peoplewho live within grassland areas of the state to takeleadership roles within their communities on behalf ofgrassland wildlife. MPF also understands that peoplewho own working lands need to make a living fromtheir property. In this issue, on pages 4 to 13, MPFexplores what could be coined the Tallgrass <strong>Prairie</strong>Economy—economic opportunities available fromhigh quality grasslands to people living in them.As a member of the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>, you are in a fairly select group. First, youare someone who has an interest in the natural world. Although it seems hard to believe,there are a lot of people who have absolutely no interest in wild things or wild places.Secondly, by accident or by choice you find yourself (most likely) living in <strong>Missouri</strong>. Thirdly,you have somehow developed a specialized interest in prairie. I am sure that a lot of you haveexperienced the polite smiles, the eye rolling and the occasional heckling that can come whenyou make the point that some grasses and flowers are native ones and therefore more desirablethan fescue and petunias. At some point, if you are particularly dedicated, you might even begiven a nickname, one that brings forth chuckles from your friends. If you are a newcomer tothe world of tallgrass prairie study, be careful: there might be a nickname waiting for you. Butthat’s o.k.—it just means that you are in a select group.The thing you will learn about prairie people is that they are very passionate about thissubject. It is a study that involves geology, natural history, botany, biology, anthropology,agriculture (both prehistoric and modern) and even political science. One of the best prairieexperts I know is an entomologist. If you can stand it long enough, listen to a specialist talkabout the complex interactions between plants and soil microbes. You will find that there isreally no complete understanding of this thing called prairie. We think we get a handle on itsometimes, but humans really don’t live long enough to witness, let alone understand, all thenatural cycles that influence prairie.We do know this for sure: <strong>Prairie</strong> is not something that evolvedin a vacuum, separate and apart from humans. It has been burned,grazed and disturbed in different ways for thousands of years. Unlikeforests, which would probably do just fine without us, our prairieswould disappear under the advance of cedar and locust and oakvery quickly without our intervention. So too would the birds andother animals that find homes in our native grasslands. Isn’t this aninteresting concept? If we humans disappeared from <strong>Missouri</strong>, withina generation, so would our prairies.I, for one, don’t plan on going anywhere anytime soon. So whilewe’re here why don’t we resubmit ourselves to being good stewardsover the land. If we currently own land, why don’t we take the dayof January 1 and assess what we can do to benefit grassland wildlife.It might be as simple a thing as minor changes to grazing timelines.It might involve getting rid of cool-season grasses long enough so that native plants can get atoehold. For the nonlandowner, it might be as simple as contacting a corporation or universityand suggesting a smarter, better way to handle campus landscaping.At the risk of repeating myself in these messages I again encourage you to consider buyinga farm within one of the prairie-chicken focus areas. The <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF)loves it when members donate money, in fact the organization wouldn’t last long if for somereason that stopped. But we with MPF know that we cannot and should not own all theprairie. We need engaged, committed and knowledgeable landowners who will pass on theirlove of the land to the generations to come. We need people who live within the focus areasto take leadership roles within their communities on behalf of grassland wildlife. We needconservation leaders dedicated to all wildlife, especially species of concern. We especially needto do a better job with our young people in connecting them to the land. Though they may livein a city, it is our responsibility to give them a chance to think beyond the interstate beltway.So what do you think? Let’s get to work.—Steve Mowry, President

<strong>Foundation</strong>the formation of the Grasslands Coalition (GC). GC partners—QuailUnlimited, the Society for Range Management, state agencies, Audubon<strong>Missouri</strong>, The Nature Conservancy, and many other groups—pool resourcesand expertise to maximize positive impacts on prairie conservation.One of the GC’s first steps was to identify core areas of the state thatwere strongholds for state-endangered greater prairie-chickens and thebest places to invest limited resources to protect and restore grasslandhabitat. These areas, called Grasslands Coalition Focus Areas, contain publicland owned by the <strong>Missouri</strong> DepartmentThe Grasslands Coalition of Conservation, the Department of NaturalResources, MPF, The Nature Conservancy andhas always appreciatedland owned by private citizens maintained ashow important cropland native prairie, pasture or cropland.and well managedThe GC has always appreciated howimportant cropland and well managed pasture arepasture are to the future to the future of grassland wildlife. Together withof grassland wildlife. species-rich prairie, working lands are a criticallyimportant part of the habitat matrix that canTogether with speciesrichprairie, working lands species. The GC also recognizes the economicsupport grassland birds and other prairie-adaptedare a critically important realities that come with making a living fromthe land and wants to work with landowners topart of the habitatimprove habitats in mutually beneficial ways.matrix that can support The GC has secured millions of dollars ofgrassland birds and otherfunding for prairie restoration, control of invasivespecies and acquisition of land for prairie wildlife.This funding has been used on public landprairie-adapted species.and also given to private landowners interestedin improving prairie habitat on (or selling) theirland. A summary of accomplishments of the GC for greater prairie-chickenrecovery efforts in fiscal year <strong>2007</strong> is on page 26.In 2005, MDC was called upon by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service toidentify the best places in the state that meet the needs of wildlife, to preventthe federal listing of any more plants or animals as threatened or endangered.As part of this Comprehensive Wildlife Strategy, MDC designated GrasslandConservation Opportunity Areas as the best places in the state to conserveprairie wildlife—these COAs include or are associated with GrasslandsCoalition Focus Areas.Today, MPF is exploring additional ways to help both private landownersmaking a living off of their land and prairie wildlife. The articles on thecarbon market and the Show Me Energy Cooperative that follow in thisissue, and articles in the same vein that will appear in future issues, explorewhat could be coined the Tallgrass <strong>Prairie</strong> Economy—economic opportunitiesavailable from high quality grasslands to people living in them.Carol Davit is the Journal editor.Frank OberleAt the time of European settlement, at least 15 millionacres—more than one-third—of <strong>Missouri</strong>’s landscapewas tallgrass prairie (see orange, above). Fewer than90,000 acres of tallgrass prairie remain today. Morethan 800 different kinds of plants can be found on<strong>Missouri</strong>’s prairies, which also support countlessspecies of birds, insects, mammals and other wildlife.Healthy native grasslands may hold promise for ourown economic benefit as well.Walter Schroeder

The Carbon MarketWhere Commerce and Conservation MeetBy Justin Johnson<strong>Missouri</strong> native grassland landowners stand to reap economic rewardsfrom the carbon market and conserve prairie wildlife at the same time.A study by David Tilmanof the University ofMinnesota shows thatprairie plantings with ahigher number of plantspecies sequester morecarbon below the groundand produce more biomassabove the groundthan a monocultureplanting.Long before the International Panel onClimate Change and former Vice PresidentAl Gore won the <strong>2007</strong> Nobel Peace Prize,scientific reports and popular media articles calledattention to the changes in our global climatecaused by an increase in greenhouse gases. FromPopular Science to Time to National Geographic toRolling Stone, it seems as though every magazinehas recently had a cover story about globalwarming or potential solutions to it, such as theuse of biofuels or land restoration projects tooffset carbon emissions.New phrases such as carbon footprint,carbon offset and carbon credits have entered thenational dialogue, but these terms are relativelyunknown to most people. As the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong><strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) searches for ways to makegrassland conservation more attractive to privatelandowners, an understanding of these newconcepts is essential.The Carbon Cycle and the Greenhouse EffectThere is a natural carbon cycle whereby livingthings use energy from the sun for fuel andproduce waste. Plants need carbon dioxideto grow and produce energy—throughphotosynthesis with the sun—in the form ofsugars and starches, and waste in the form ofoxygen. We humans breathe that oxygen andproduce carbon dioxide as waste. It is a verycomplicated cycle, one that keeps the Earth’sclimate relatively balanced as long as the energyand waste produced in one cycle are equal.When humans burn fossil fuels like coal andoil that were produced many carbon cycles ago,we overpower the natural carbon cycle’s ability

David Tilmanto absorb the waste. This leads to an increasein gases in the atmosphere (greenhouse gases),most notably carbon dioxide, but also methaneand nitrous oxide. Those gases, along with watervapor and ozone, trap heat and warm the planetthrough the so-called Greenhouse Effect, whichis not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, withoutthe natural insulation of the greenhouse gases,the Earth would not be suitable for plant andanimal life. Over time, however, the increasingconcentration of greenhouse gases has trappedmore and more heat, which has led to what wenow call climate change or global warming.These changes include increased melting of icecaps and glaciers, rising seaInstead of growingcorn or soybeansfor biofuels on ourmost fertile soil,we can producebioenergy bygrowing prairieplants on marginalsoils withoutirrigation andwithout fertilizeror pesticidesthat can pollutegroundwater. Wedo not have tochoose betweenfood and energy.levels and huge potentialchanges in our currentrainfall amounts and windpatterns.Measuring Our Impact:Carbon Footprints andCarbon CalculatorsAs humans attempt tocome to grips with the partwe are playing in changingthe Earth’s climate, theconcept of the carbonfootprint has emerged.The idea is that all fuelconsumptiveactivities,from driving a car toheating and poweringa home to buying andconsuming productsproduced with energy, contribute carbon tothe atmosphere. Since most people do not havethe time or resources to do a personal carboncalculation, averages for American individualsand households have been developed. There area number of carbon calculators on the Internetwhere individual or family information, such astype of car, number of miles driven, size of home,cost of energy bills and number of miles flowncan be entered to produce a rough estimatedvalue of the amount of tons of carbon you oryour family are adding to the global total. Thatis your carbon footprint. The two most widelyaccepted carbon calculators are those run byEnvironmental Defense and Carbonfund.org.The best things anyone can do for the climateare to reduce one’s carbon footprint through drivingless, using less energy or buying less stuff. Inalmost all cases, those changes will save moneytoo. The benefits of recycling, carpooling andproper insulation have been touted for decades.A current positive trend is the use of compactfluorescent light bulbs. Replacing drafty windowsor inefficient appliances with EnergyStar productscan also make a big difference. Even regularlychecking your car’s air filter and tire pressure tomaximize fuel efficiency can have an impact. Atsome point, however, you will have reduced yourcarbon footprint to a point where it becomeseither too costly or too inconvenient to go further.At that point, the slogan of Carbonfund.orgcomes into play: Reduce What You Can, OffsetWhat You Can’t.Carbon Offsets and CreditsThe concept of carbon credits came into beingin late 1997 with the development of the KyotoProtocol, named for the Japanese city in whichinternational negotiations were held. A successfulmodel for carbon credits came from the U.S.program begun in the 1980s to reduce acid rain,where companies that produce an excess of sulfurdioxide and nitrogen oxides trade credits withthose who do a better job of reducing contaminants.That trading system was localized, sincepollutants from one specific location show up asacid rain in another specific location. The idea isthe same with carbon credits except on a globalscale, because all carbon dioxide emissions affectthe global climate equally. Each industrializednation is given an annual carbon emissions cap itmust meet, and nations that produce more thantheir cap must trade or purchase credits fromthose who are below their cap. All EuropeanUnion (EU) nations have ratified the Kyoto protocoland have developed a complicated carbontrading system called the Emissions Trading

Scheme (ETS) where individual businesses buyand trade credits to stay below their cap. In general,credits are measured in tons of carbon, andthe price of a carbon credit fluctuates based onsupply and demand.It is important to note that the United Statesdoes not have a legally enforceable carbon tradingsystem because it has not ratified the Kyoto protocolor passed legislation that includes a carboncap. All carbon trading in the United States isdone on a voluntary basis, and nearly all throughan entity called the Chicago Climate Exchange(CCX). Because of this, the price of carbon ismuch lower in the U.S. than in Europe, approximately$4 on the CCX compared to $30 on theEU’s ETS.<strong>Prairie</strong> plants sequester largeamounts of carbon in the soil, up to1.8 tons of carbon per acre per year.Conservation Research Institute and Heidi NaturaThe Potential for Carbon Creditsto Help Save Our Native GrasslandsIn the voluntary carbon market here in theUnited States there are two types of carbon offsetprojects being promoted. One is sustainableenergy, primarily the construction of wind energyturbines that produce no carbon emissions. Thesebenefits are only realized, however, if the energyproduced by wind turbines replaces traditionalcoal-derived energy rather than just adding tothe total. The other type of project is designedto store carbon in plants. The technical term forthis carbon storage is sequestration, primarilythrough the planting of trees, which leaves thesoil undisturbed and builds up carbon as the treesgrow. Trees are approximately 50 percent carbon,depending on the species. As an advocate forprairie conservation, MPF believes that anotheroption should be placed on the table: grasslandreconstruction and permanent protection.The tallgrass prairie once stretched fromIndiana to Nebraska and from North Dakota toTexas. It was a vast grassland the first Americanscalled home, and it held enormous naturalresources, including abundant wildlife, crystalclear water and hundreds of species of nativeplants with many uses. Those plants producedextensive root systems and deep, rich topsoil. Anenormous amount of carbon was released into the

atmosphere when the tallgrass prairie was brokenfor the first time, and that highly productive soilliterally fed the growth of America. Along theway, more than 99 percent of the original tallgrassprairie was lost, making it more rare thantropical rainforests. Most of what is left is foundin areas too rocky to plow. <strong>Prairie</strong> restorationsand reconstructions can never replace originalprairie diversity, but relatively inexpensive plantingson marginal cropland or erosion-prone areashave been promoted by the government for 20years through the Conservation Reserve Program.MPF is now asking private citizens to step forwardto help restore more of the missing prairiefor many important uses.Amid talk of dependence on foreign oil andunsustainable energy use, the tallgrass prairie is aquiet place to escape and reflect. But it is so muchmore. Those deep roots sequester carbon, soak inrainwater and generally serve as the best naturalfilter ever imagined. The grasses and wildflowersabove the ground can be cut and burned incoal-fired power plants to reduce fossil fuel usagein electricity generation; turned into pellets forhome heating instead of using electricity, naturalgas or propane; or converted into cellulosicethanol to replace gasoline. Instead of growingcorn or soybeans for biofuels on our most fertilesoil, we can produce bioenergy by growing prairieplants on marginal soils without irrigation andwithout fertilizer or pesticides that can pollutegroundwater. We do not have to choose betweenfood and energy. Right now these “greener” biofuelsindustries are trying to get off the ground,with the biggest limiting factor being the uncertainsupply of renewable plant material called biomass.We need more restored grassland acres toencourage investment in these new technologies.Recent studies show that restored prairie cansequester carbon in the soil and roots at the rateof 1.8 tons of carbon per acre, per year. Otherstudies show that carbon continues to build upbelow ground for at least 60 years, so that oneacre of restored prairie can sequester more than100 tons of carbon. Unlike reforestation projects,where nearly all of the carbon is stored aboveground, once the carbon is sequestered deepwithin the prairie soil, it is not released when theabove-ground resource is cut or burned. In fact,burning and grazing prairie in a responsible rotationplan encourages the growth of the roots andthereby sequesters carbon more quickly.Land providing an economic return to thelandowner and a value to society at large willbe easier to justify and protect than somethingviewed only as visually appealing and valuable forwildlife. The question is, what kind of fundingcan landowners expect to get out of this?Show Me the Money:How <strong>Prairie</strong> can be ProfitableAs Congress considers new programs, regulationsand incentives for reducing carbon emissionsand increasing the use of bioenergy, the potentialfor profitable prairies is just now coming intofocus. See the feature on the Show Me EnergyCooperative on the next page to learn about thefirst company in <strong>Missouri</strong> planning to turn grassinto heat, power and ethanol. If, as expected,the U.S. adopts some form of an annual carbonemission “cap and trade” system in the next fewyears, every industry that emits carbon—and thatis practically everything—will be required to getin the game, which will rapidly increase the valueof carbon. Given the huge amount of carbon theU.S. produces, nearly double the entire EuropeanUnion, it is not unreasonable to assume that theprice of carbon in the U.S. market might exceed$50 per ton if a serious effort is made to reduceemissions. Even if the size and efficiency of theU.S. market keeps the price of carbon at theEuropean level of $30 per ton, it is easy to seehow a landowner with 40 acres of grass, capableof storing 4,000 tons of carbon in the soil androots and producing renewable energy year afteryear would stand to profit. The challenge forMPF and other conservation groups is to designland management regimes that produce value forboth landowners and wildlife.Justin Johnson is the executive directorof the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>.It is possible toregister and be paidfor carbon credits withthe Chicago ClimateExchange, http://www.chicagoclimatex.com,but unfortunatelyall grass plantings,regardless of species,are treated the sameat this time.

Frank OberleNative grasslands like this can be cut for bioenergy and support prairie wildlife at the same time.For the Show Me EnergyCooperative, the Future is NowBy Justin JohnsonHayed, native prairie plants can be salvagedfor home-heating pellet production. As oilapproaches $90 per barrel, biomass can bea viable energy option even without thebenefit of subsidies.Steve Flick has reason to smile. After morethan 20 years of thinking about newenergy technology, his Show Me EnergyCooperative is due to come on-line in January2008. And if he can keep up the hectic paceof the last year for another two, much of rural<strong>Missouri</strong> may be smiling along with him. Theplan is to first make home-heating pellets fromplant material that can also be used by traditionalutilities to burn along with coal to produce electricity.Phase two would create a small cellulosicethanol plant, and phase three would captureenergy on site to produce electricity.10

Located in Centerview not far fromWarrensburg, the Show Me Energy Co-opdoesn’t look like much, but that is by design. Theprimary storage buildings are made of recycledcement blocks, the office park lighting is run onsolar panels and the business office is the definitionof no-frills. Rather than look like a successfulbusiness, Flick and the rest of his board intendto deliver. After years of thinking and monthsof planning, the company officially opened onJune 15 after $7 million was raised by local investors.What makes Show Me Energy unique andexciting is its business concept. As a co-op, thecompany is essentially owned by approximately450 farmers from a 22-county area. Each boughtshares, with a minimum investment of $5,000,and each is committed to bringing a certainamount of biomass to the factory for production.When I visited the site in October, two largescalepellet machines were still due to be deliveredand set up. The smaller test mills were grindingup bulk plant material and churning out greenpellets, which include a small amount of dye formarketing purposes. “The green color isn’t necessary,”said Flick, “but we decided it was a way tobrand our product in the marketplace.”By January 2008, Flick said thefacility will be capable of producing120 tons of fuel pellets perday. When full capacity isreached in 12 to 24 months,that total would be 100,000tons per year. The key willbe getting plant materialsto the site on a regularschedule. Producers will bepaid based on the weight,moisture content and energyvalue—measured in BTUs(British Thermal Units)—of theirbiomass, and bonuses will be paid tothose who deliver on time. Eventually, the pelletsmay be shipped to and from the plant via the railline near Show Me Energy’s site.“As we get started, I’m not asking farmers tochange what they’re already doing,” Flick said.“We can make pellets out of hay, corn stover orthe leftovers from our seed-cleaning operation.We want to help local producers get some valueout of what they used to consider waste.” In fact,Flick, as president of a seed company located inKingsville, knows there is a lot of what he callsagricultural residue out there. Whether its nativebig bluestem and Indian grass or non-native tallfescue, after seed is harvested, approximately twothirdsof the plant can be salvaged for pelletproduction.The cost of propane has beenrising, and those who use it forhome or agricultural heatinghave been looking for alternatives.According to theShow Me Energy Co-op,the same amount of energyin a gallon of propane thatcosts $1.69 can be producedfrom just 69 cents worth ofits pellets. Flick says that oneton of plant material, on average,contains the same energy value as2.5 barrels of oil. As oil approaches $90per barrel, biomass can be a viable energy optioneven without the benefit of subsidies. In effect,Show Me Energy can pay producers more fortheir hay or crop residue than they would havegotten before and can sell the resulting energySteve Flick, boardpresident of Show MeEnergy Cooperative, isworking with the morethan 400 other ownersof the cooperative toturn plant material intohome-heating pellets,which also can be usedby traditional utilities toburn along with coal toproduce electricity.Photos Justin Johnson11

product cheaper than an equivalent amount ofoil, propane or natural gas.Flick is anxious about the next few months.Phase one, the pellet production, is set to beginin earnest in January 2008, and he will findout in February whether Show Me Energy willreceive a federal energy grant to accelerate phasetwo, the ethanol plant. With the grant, constructionwould begin in June 2008 with a goal ofthe facility being fully operational by September2009. The company is already working withBlack and Veatch engineering on a design thatwould produce 2 million gallons of ethanol peryear. When the pellet production and ethanolplant are both at full capacity, Flick says the facilitywill be processing 700 tons of plant materialper day or approximately one-half billion poundsper year.These are all huge numbers, but they aredwarfed by the amount of fuel Americans useeach year. It is estimated that ethanol plants willproduce more than 500,000 barrels per day by2012, approximately 8 billion gallons of fuel, butthat represents only five percent of total gasolineuse. And the 120 tons of fuel pellets that ShowMe Energy will be producing per day in January2008 could be consumed in 20 minutes in a coalfiredpower plant.Because of those staggering figures, energyconsultant David Morris says that biofuels shouldbe viewed as a rural development strategy first andan energy strategy second. “Exactly,” agreed Flick.“And that’s why we set this up as a co-op. Theprofit from producing this energy needs to staywith local people in local communities.”If this plan works, Flick hopes to sell the winningformula to other groups of investors to replicatethe Show Me Energy Co-op model across<strong>Missouri</strong> and the Midwest. Reluctant to call ita franchise system, Flick is proud of this businessmodel, which has been developed over yearsthrough trial and error. He estimates that anotherseven facilities could probably be supported bybiomass just in <strong>Missouri</strong>. “I’ve put a lot of mymoney and time into this, and I want to see itsucceed,” he says. “It’s important for rural peopleand for the country as a whole.”12

Photos Justin JohnsonWhen the Show Me Energy Cooperative’s large-scale pellet mills are operational in January 2008, this huge pile ofbiomass—600 tons of residue from a seed harvest—will be processed in approximately one week. From left are JoeHorner, with the University of <strong>Missouri</strong> Commercial Agriculture Program, and at right, Ryan Milhollin, also with theUniversity of <strong>Missouri</strong>, with Steve Flick.How Biomass Energy Can BenefitGrassland Wildlife and Water QualityAccording to Flick, the best time to cut grassfor biomass energy is after the hay is past itsprime value for livestock. In fact, after the firstfrost, the grass is dry, bleached and ready to bemade into bioenergy. He says that nitrogenfixinglegumes, such as Illinois bundleflower,in combination with big bluestem and Indiangrass, produce a high BTU value. If the marketdevelops to a point where landowners canreceive a strong price per ton, fields couldbe cut well after the primary nesting season,leaving six inches above the ground to providenesting cover for the spring. While prescribedburning and patch grazing remain importanttools in prairie management, some acrescould be cut completely or burned to promotestrong regrowth and to provide bare groundfor mating and brood-rearing of groundnestingbirds. Landowners could also receivepayments for carbon credits and perhaps forassisting grassland wildlife. As research fromthe University of Minnesota has shown, a mixof 16 common prairie grasses and wildflowersproduces more biomass than a monoculture ofswitchgrass, all without irrigation or fertilizer,which improves groundwater quantity andquality, respectively.Examining the <strong>Number</strong>s• At full capacity, the Show Me Energy Co-op will process700 tons of biomass per day, which is approximately250,000 tons per year.• If seven identical facilities were built in <strong>Missouri</strong>, the totalbiomass needed would be 2 million tons annually.• A <strong>Missouri</strong> hay prairie produces between two and four tonsof biomass per acre, so up to 1 million acres of grassland couldbe needed.• There are approximately 1.5 million acres currently enrolled inthe Conservation Reserve Program in <strong>Missouri</strong>, but landownersare penalized for cutting their CRP acres for hay.• At full capacity, the Show Me Energy Co-op will produce 100,000tons of fuel pellets. That is 5 million 40-pound bags, which retailfor approximately $3 per bag, or a total of $15 million.Justin Johnson is the executive director of the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>. Steve Flick, boardpresident of Show Me Energy Cooperative,can be reached at 816-597-3822 orsflick@goshowmeenergy.com.Visit www.goshowmeenergy.comfor more details on the cooperative.13

Natural Community ManaText and photos by Robert N. Chapman14

gement Benefits QuailAs a wildlife biologist, I amoften confronted with thenotion that quail are “edge”species, not only by private landownersand armchair biologists, but also byprofessional conservationists. In his 1933book Game Management, Aldo Leopoldpostulated the Law of Interspersion and theedge-effect. The edge-effect asserts that thepresence of some wildlife species, includingnorthern bobwhite quail, is a phenomenonof edges and occurs where all habitatcomponents come together, i.e., where theedges meet. The more interspersed thosehabitat components become, the greaterthe amount of edge. This increase in edgetheoretically results in an increase in quailabundance.The landscape in which quail calledhome in the early half of the twentiethcentury, when the study of wildlife andtheir habitat associations began, was muchdifferent than today. During that time,most of the original prairies and savannashad been or were being converted tocropland. Forests and woodlands had beenor were cleared of trees. The landscape wasdotted with many small farms and smallfields. Tall fescue was not in North Americayet so pastureland was still dominatedby native grasses. Quail flourished underthese conditions, and early biologists likeLeopold noted that quail were typicallyfound along fence and hedgerows adjacentto agricultural crops and were thereforeclassified as an “edge” species. Thecategorization of quail as an edge speciescontinues today. But, does it really makesense to call quail an “edge” species?15

The northern bobwhitepopulation trend ilustratedabove is basedon Breeding Bird Surveyresults from 1966–2003.Percent Change per YearLess than -1.5-1.5 to -0.25> -0.25 to 0.25> 0.25 to +1.5Greater than +1.5BBS mapThe Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), a cooperativeeffort of the U.S. Geological Survey and theCanadian Wildlife Service to monitor the statusand trends of North American bird populations,has been used since the late 1960s to documentrange-wide status of bird populations. The BBShas documented quail population declines at arate of almost 3% per year (see figure above).However, there are locations where quail populationsare increasing. These are mainly in prairielandscapes that are relatively devoid of row cropagriculture. Quail populations in these areas areincreasing at a rate of more than 1.5% annually.Quail populations can increase in <strong>Missouri</strong> aswell. Several Farm Bill programs are encouragingthe addition of quail-friendly habitat practices onagricultural ground. These programs primarilytarget an increase in the amount of suitable habitatalong field edges. However, edge managementdoes not maximize usable space. Managing forthe potential natural plant community across thelandscape will maximize the amount of usablespace available for quail. What would happen ifyou managed an entire field the same way youwould manage the edge for quail?The term “usable space,” as proposed by FredGuthery at Oklahoma State University, implies a“suitable, permanent cover-situation” or simplymaximizing usable space in time. In managementterms this means the maximization of habitat(space) available to quail all year (time). Usablespace for quail should consist of the proper quantitiesof low shrubby cover and herbaceous coverinterspersed so that certain distance conditionsare met. Guthery’s range in conditions included30–60% canopy coverage of low-growing woodyshrubs within a matrix of 40–70% herbaceouscover. The attributes should be arranged so thatclumps of shrub cover are no further apart than30 yards. This mixture of habitat attributes wouldprovide good habitat conditions throughout allseasons of the year. All of these habitat attributescan be provided when managing for the appropriatenatural community.Paul Nelson describes <strong>Missouri</strong>’s 85 naturalcommunities in his book The Terrestrial NaturalCommunities of <strong>Missouri</strong>. At least eight of the 12prairie natural communities and all six savannanatural communities can be managed for quailwith great success. Quail can also be abundant ineight of the 18 woodland natural communitieswhere canopy coverage of trees averages 50% orless. The key to natural community managementis to identify which natural community bestdescribes the particular parcel of land in question,restore the natural potential vegetation species,and reintroduce the natural processes (i.e., fireand light grazing) that developed and maintainedthat system.Natural community management for quailprovides for nest-site saturation. The entire fieldnow provides for an exponential increase in availablenesting sites. The more nest sites available,the greater the annual production of young.Furthermore, by increasing the amount of availablenesting cover across an entire field, ratherthan just the edges, the amount of time it takes aquail nest predator (skunk, raccoon, fox, cottonrat, etc.) to locate a nest increases. And becausethere are more nests in the field, the chances ofany one nest succumbing to predation decreases.Consider that other bird species (such as dickcissels,eastern meadowlarks, grasshopper sparrowsand upland sandpipers) also nest in similar habitatas quail, which further decreases the chancesof nest predation on any individual nest.Natural community management furtherreduces predation by reducing the cone-of-vul-16

Cone-of-VulnerabilityRobert N. Chapmannerability. Cone-of-vulnerability describes anindividual’s vulnerability to avian predators.Imagine a cone-shaped volume of space above aquail head. As altitude increases, the volume ofthe cone increases. Therefore the wider the cone,the more vulnerable the quail will be to detectionby an avian predator. The cone-of-vulnerabilitycan be reduced by providing maximum usablespace through habitat management. Many speciesof native grass have an umbrella-like growthstructure, especially the bunch-type grasses likelittle bluestem, broomsedge and dropseeds. Notonly do these grasses provide excellent nestingstructure, they also serve to reduce the exposureof quail and their young to avian predators. Thelong leaves of bunch grasses grow up and out,resulting in a canopy over the space betweenthe clumps. The space between the grass clumpscontains ample bare ground for increased mobilityand is where many plant species that providefood grow. The plants that grow in these spacescontribute to a field’s vegetation diversity, whichin return increases insect biomass, the criticalfood item for growing quail chicks. Low-growingshrubs such as sumacs, American plum, gray andRobert N. Chapman Robert N. ChapmanThe above left photoof a prescribed prairiefire reveals burnedclumps of little bluestemgrass, in or againstwhich quail and otherground-nesting birds willnest. The photo at leftillustrates the umbrellalikegrowth structureof little bluestem; bygrowing up and out,the leaves of this andother native bunchtypegrasses create acanopy under whichquail can travel “undercover,” reducing a quail’scone-of-vulnerability,as illustrated above. Inbetween grass clumps,bare ground providesquail chicks with travellanes, and other plantspecies, such as thelegumes shown in thelower left photo, growand attract insects andprovide seeds, both ofwhich are eaten by quail.17

Through natural community management, the amount of space used by quail(“usable space”) on a given property can be maximized. As shown in the photosabove, prairies and other grasslands with a diversity of vegetation, including lightshrub cover, is compatible with overall prairie management and also providesoptimal habitat for quail.Robert N. Chapman Robert N. Chapmanrough-leaved dogwood, and indigo bush providesimilar overhead protection from predators aswell as thermal relief from summer heat, wintercovey roosts and additional food. Thicker shrubslike blackberry provide good predator escapecover.Maximizing usable space through naturalcommunity management integrates food resourceswithin other habitat components. This meansthat quail can reduce their movements fromroosting and nesting areas to food areas. The lessmoving around the quail do the less exposed theyare to weather and predators. It also reduces theamount of energetic outputs needed to locate andtravel to feeding areas. Food plots become unnecessarybecause native plants are more dependablefood resources than food plots. Native plantsare adapted to local climates and are often moreresistant to extreme environmental perturbations,such as drought, than food plot grains. Foodtherefore does not become a limiting factor withnatural community management.Several examples of natural communitymanagement benefiting quail already exist in<strong>Missouri</strong>. Many private landowners have beenastounded by the increase in quail abundance ontheir properties with the restoration of prairie,savanna and woodland natural communities.Most readers of the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal haveheard the story of <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>(MPF) member Frank Oberle whose neighborsaccused him of “holding all the quail” on hisrestored prairie. Many MPF-owned prairies haveabundant quail populations as well. I personallyhave experienced flushing four coveys of quail inone hour on MPF’s <strong>Prairie</strong> Fork Expansion inCallaway County and heard multiple bobwhitecalls on Golden <strong>Prairie</strong> in Dade County.The <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation(MDC) is practicing natural community managementthat benefits quail on several conservationareas. At Bushwhacker Lake Conservation Area inVernon and Barton Counties, White River TraceConservation Area in Dent County and Cover<strong>Prairie</strong> and Tingler <strong>Prairie</strong> Conservation Areas inHowell County, MDC biologists practice natural18

community management and have some of thehighest quail densities in <strong>Missouri</strong>. Populationdensities on these areas frequently surpass onebird per two acres. Hi-Lonesome <strong>Prairie</strong> inBenton County is managed under a landscapescalenatural community approach that includespatch-burn grazing, which results in documentedgood quail habitat. Quail populations are likewiseabundant in many state parks. Rock BridgeMemorial State Park in Boone County has quailpopulation densities approaching one bird peracre. The quail on these properties and others likethem are abundant because of excellent naturalcommunity management. Additionally, the quailpopulations on these lands serve as a source forthose properties surrounding them.So, back to the original question: does itreally make sense to call quail an “edge” species?The answer to this question is complex andprobably is a matter of scale. Early explorers in<strong>Missouri</strong> described an abundance of quail longbefore mechanized agriculture found its wayto <strong>Missouri</strong>. Quail were subsequently pushedto margins of fields, as that is where the onlysuitable habitat remained, and concurrentlydeemed “edge” species. Modern agriculture hasall but removed these marginal habitats. Newprograms described in the Farm Bill will ensurethat many of these field edges are restored tosuitable quail habitat. However, if growingan agricultural crop is not your primary landmanagement objective and you want to produceas many quail as the land is capable, then look nofurther than maximizing the amount of usablespace available to quail by incorporating naturalcommunity management.Robert N. Chapman is a wildlifemanagement biologist with the <strong>Missouri</strong>Department of Conservation in Rolla.His professional interests include researchingthe response of plant communities andwildlife populations to fire.ReferencesThe quail illustrations byMark Raithel in this articleare used courtesy of the<strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Conservation, andwere created for theDepartment’s newlyrevised “Your Key to QuailHabitat 2008,” a free wallcalendar designed to helplandowners meet theirwildlife managementgoals. For nearly every dayof the year, the calendarnotes key events in thelife history of quail andother grassland birds,including prairie-chickens,bobolinks and scissortailedflycatchers. It alsoprovides reminders aboutthe best times to performmanagement activities,such as prescribed burningand light disking. Toreceive a copy of thecalendar, call your nearest<strong>Missouri</strong> Department ofConservation office andask to speak to a privateland conservationist.Guthery, F. S. 1997. A philosophy of habitat management for northern bobwhites.Journal of Wildlife Management 61(2): 291–301.Hiller, T. L., F. S. Guthery, A. R. Rybak, S. D. Fuhlendorf, S. G. Smith, W. H. Puckett,Jr. and R. A. Baker. <strong>2007</strong>. Management Implication of Cover Selection Data:Northern Bobwhite Example. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(1): 195–201.Johnson, J. 2006. MPF Celebrates 40 Years “Our Way.” <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> Journal.27(4): 18–21.Kopp, S. D., F. S. Guthery, N. D. Forrester and W. E. Cohen. 1998. Habitatselection modeling for northern bobwhites on subtropical rangeland. Journal ofWildlife Management 62(3): 884–902.Leopold, A. 1933. Game Management. Charles Scribner’s Sons.Nelson, P. W. 1985. The Terrestrial Natural Communities of <strong>Missouri</strong>.<strong>Missouri</strong> Natural Areas Committee. 550 pp.Sauer, J. R., J. E. Hines, and J. <strong>Fall</strong>on. <strong>2007</strong>. The North American Breeding Bird Survey,Results and Analysis 1966 - 2006. Version 7.23.<strong>2007</strong>. USGS Patuxent WIldlifeResearch Center, Laurel, MD.19

<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park atby Brian Miller25The foresight of some great prairieenthusiasts of the 1970s led tothe largest publicly owned prairielandscape remaining in <strong>Missouri</strong>today: the nearly 4,000-acre<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park, which marks its25 th anniversary in <strong>2007</strong>.<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park visitors value the opportunity tosee bison and elk roaming and grazing over the rollinglandscape of the park. Nine bison were reintroducedto the park in 1985 and five more were added in 1987to replicate the grazing patterns and disturbance thatthese large herbivores once provided. A herd of up to130 bison now grazes over 2,686 acres. In 1993, elkwere reintroduced to establish different grazingpatterns and disturbance. There are 30 elk grazingup to 400 acres today.NOppadol Paothong /MDC21

<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park offersexpansive prairie views,but also importanthabitat for hundredsof plants and animals,including uncommonspecies like the prairiemole cricket, regalfritillary butterfly,northern harrier,greater prairie-chicken,southern prairie skinkand Mead’s milkweed.DNR fileJim Rathert/MDCThe park’s East Drywood Creek is the state’s most outstanding prairie headwatersstream and provides habitat for aquatic prairie species.<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park is one of the grand gems of<strong>Missouri</strong>’s state park system and certainly one ofthe best remaining examples in the country of athriving prairie landscape. Not only has the parkgrown in size and facilities over its 25 years, butit has also become more biologically diverse andnow functions much like presettlement prairie.Nearly 600 plant species have been documentedat the park, and in addition to the introducedbison and elk that roam the park, the area also ishome to greater prairie-chickens, coyotes, deer,bobcats, burrowing crayfish, northern crayfishfrogs, bullsnakes and many other animals. <strong>Prairie</strong>State Park contains 690 acres of outstandingprairie natural communities, which are designated<strong>Missouri</strong> natural areas.In the 1970s, an effort to preserve remainingprairie in <strong>Missouri</strong> was fostered between the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF),The NatureConservancy, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department ofConservation and later the <strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Natural Resources. The effort was furtherenergized when wildlife biologist and MPF cofounderDonald M. Christisen advocated for thepreservation of any remaining prairies of any size.According to William D. Blair, Jr., in hisbook Katharine Ordway, The Lady Who Savedthe <strong>Prairie</strong>s, “the <strong>Missouri</strong> effort was capped in22

1978–79, after the Bicentennial, by the acquisitionof land for a … <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> StatePark.” Ms. Ordway was a philanthropist fromthe East Coast who visited prairies in BartonCounty in 1972 with Lowell Pugh and the lateDon Christisen, board members of MPF, andultimately gave tens of millions of dollars throughThe Nature Conservancy and other groups topreserve Midwestern tallgrass prairie. (See theprofile of Lowell on page 40 of the summer <strong>2007</strong>issue of the Journal for more information.)On June 3, 1980, the <strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Natural Resources received the title to 1,520acres of rolling prairie landscape in BartonCounty, acquired at $719,000 from The NatureConservancy for the development of <strong>Prairie</strong> StatePark. According to the book Exploring <strong>Missouri</strong>’sLegacy, State Parks and Historic Sites (Universityof <strong>Missouri</strong> Press, 1992), this came about due toseveral factors: the sudden interest of a landownerto sell a key undisturbed prairie tract, the awarenessof Nature Conservancy and MPF officials ofthe landowner’s desire to sell, and an interest-freeloan from Katharine Ordway to pay for it. Othergifts soon increased the acreage to 1,840 acres.In 1980, Larry Larson, then a naturalist atKnob Noster State Park and former MPF boardmember, moved to Liberal, and oversaw thepark’s development. Larry’s ambitious plan forthe park was published in the January 1982 issueof the Journal (see the winter <strong>2007</strong> issue of theJournal for more on Larry’s career).In the spring of 1982, a park residence andshop area were built in order to have a workingcrew on-site to begin the job of establishing andmanaging the park. Twenty-five years ago, onDNR file25Larry and other park staff knew that the key toJune 27, 1982, the park was dedicated, and thenGovernor Christopher Bond proclaimed <strong>Prairie</strong>Day in <strong>Missouri</strong>, “to praise those preservationand conservation organizations and individualswho have worked so hard to protect <strong>Missouri</strong>prairie.”At that time, park facilities included a picnicarea, primitive campground and three trails.long-term success, acceptance, and more importantly,the key to preserving prairies all acrossthe country would be to interpret this resourceto the park’s present and future visitors. Hence,interpretive staff was hired and programs wereinitiated. On June 11, 1988, the visitor centerwas dedicated, and interpretive programmingbegan to increase. The first <strong>Prairie</strong> Jubilee washeld in 1991 and continues biennially to celebrate<strong>Missouri</strong> tallgrass prairie. In conjunctionwith <strong>Prairie</strong> Jubilee 2000, the park was chosen asthe final site for the “Lek Trek,” the GrasslandsCoalition-sponsored walk across <strong>Missouri</strong> to raisepublic awareness of prairie-chickens and grasslandconservation. The next <strong>Prairie</strong> Jubilee will beoffered in September of 2008.Over the last 25 years the park has grownto 3,942 acres with the assistance of The NatureConservancy, MPF and other agencies, organizationsand individuals. Currently, the park has fiveconnecting hiking trails—totaling 12 miles—thatprovide visitors the opportunity to experiencethe vastness, beauty and solitude of the tallgrassTop left, a sign in thepark indicates thelocation of Regal <strong>Prairie</strong>Natural Area, namedfor the regal fritillarybutterfly. Regal isone of the park’s fourstate natural areas,designated as such forthe outstanding qualityof the prairie communitytypes these areasrepresent.Below, participantsto the park’s biennial<strong>Prairie</strong> Jubilee eventparticipate in a gameenjoyed by early prairiepioneers.<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park Photo23

<strong>Prairie</strong> State Parkis located in BartonCounty, where 86 percentof the land wasprairie before Europeansettlement. Accordingto the book Exploring<strong>Missouri</strong>’s Legacy, StateParks and Historic Sites,the prairies of thissouthwestern region ofthe state were huntinggrounds of the Osagetribe, and between1700 and 1775, a groupof the Osage lived on ahigh, open hilltop nearthe Osage River valleythat today has been preservedas Osage VillageState Historic Site notfar from the park andLamar, Mo. At its height,the village contained2,000 to 3,000 peopleand about 200 lodges.<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park Photo<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park Photoprairie. Camping isavailable in a campground,and there isalso a camping area forbackpackers.<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park ismade up of numeroustracts of varying quality.The most outstandingexamples of the park’sprairie types are statedesignatednatural areas:Regal <strong>Prairie</strong> NaturalArea (240 acres), named“the park is a placewhere prairie, asa landscape, cansurvive—expansive,dynamic, self-renewing,a living tribute to a largelyextinct componentof our natural past.”—from Exploring <strong>Missouri</strong>’s Legacy,State Parks and Historic Sitesfor the regal fritillary butterfly; Tzi-Sho <strong>Prairie</strong>Natural Area (240 acres), named for “tzi-sho,” aNative American word for “sky people,” one ofthe divisions of the Osage tribe; East DrywoodCreek Natural Area (50 acres), named for thestate’s most outstanding prairie headwatersstream along which the natural area is situated;and Hunkah <strong>Prairie</strong> Natural Area (160 acres),named for “hunkah,” a Native American wordfor “Earth People,” another division of the Osagetribe. Currently, park staff is preparing to nominatenearly the entire park for a new landscapescalenatural area.At the time of its purchase, other areas of thepark were overgrazed, degraded prairie remnantsdissected by overgrown fencerows, which onceprovided perches and corridors for predators andinterrupted the prairie viewscape. Some prairiecommunities were described as hay meadows,which historically were preserved for their highhay yields and because of the area’s rocky soil,which made the land unsuitable for productivecultivation. Small segments of land purchasedfor the park had been strip-mined and have sincebeen reclaimed.Today, nearly all of the old fencerows havebeen removed and the strip mines have beenreclaimed. The park’s prescribed burn programhas dramatically increased from two small unitsin the early 1980s to more than 1,600 acresburned in 2006. Park staff attempts to burnabout a third of the park each year, rotating sea-24

25DNR fileDNR filesons and prairie units. Along with the prescribedburning, rest and light bison grazing have restoredold prairie remnants to reasonably good qualityprairie, providing connectivity to the best qualitysites. Those hay meadows have been allowed toreinvest nutrient cycling and recover a flourishinginvertebrate community, including populations ofsoil microbes, while late-nesting birds have onceagain become successful.Ongoing research determines the impacts ofpark management and evaluates the changes inquality of each management unit. The park’s mostimportant research is its long-term vegetationmonitoringproject that has been conductedfor more than 10 years. Park staff also monitorsbirds, butterflies, amphibians and exotic species.Periodic research on the park initiated byuniversity professors and students clearly increasesthe knowledge base for prairies across the countryand will continue to be encouraged. To date,there have been at least 24 research projectspublished as a result of data collected from siteswithin the park.Organizations like MPF were and still areinstrumental in preserving <strong>Prairie</strong> State Park. Likethose who invested so much in the past to establishthe park, people like MPF members—whoare willing to invest time, talent and funding—are vital for the future of prairie in <strong>Missouri</strong>.The <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Natural Resourcesis pleased to recognize the park’s 25th year andintends to make the next 25 years as successful asthe first.Check out park events listed on page 35, andcome and experience this prairie landscape foryourself. Traverse miles of hiking trails, searchfor the inconspicuous Henslow’s sparrow, watchthe bison graze amongst the clouded shadows onthe grass, or watch the orange glow of an eveningprairie fire. Your visit will likely take you back towhat our first explorers must have felt when theyemerged from the woodlands to see an endlesscarpet of flowers and waving grass.Brian Miller is the Natural Resource Stewardat <strong>Prairie</strong> State Park with the <strong>Missouri</strong>Department of Natural Resources. He hasbeen managing prairies and savannas for theDivision of State Parks since 1997 includinghis current position managing <strong>Prairie</strong> StatePark. Brian lives on the prairie with his wifeGayla and their three children.<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park offersa visitor’s center (above),picnicking, hiking,wildlife viewing, naturestudy, a campground andcamping for backpackers.If you have furtherquestions, contact<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park at417-843-6711 or visitwww.mostateparks.com. If you would liketo receive the park’selectronic newsletter,the Tallgrass Tribune,send an e-mail messageto prairie.state.park@dnr.mo.gov.25

<strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken RecoveryAccomplishmentsIn 2006, the <strong>Missouri</strong> ConservationCommission made a bold decision. TheGovernor-appointed commissioners approveda five-year plan to increase the state’s greaterprairie-chicken population to 3,000 and holdit there for at least 10 years before delisting thisstate-endangered bird. <strong>Prairie</strong>-chickens havedeclined from hundreds of thousands in the 19thcentury to only about 500 individuals currentlyremaining in <strong>Missouri</strong>. They are imperiled todaybecause of outright loss of prairie habitat anddegradation of what few small prairie remnantsremain. Not only will the plan help prairie-chickens,but all the other prairie species that requirehigh quality grassland habitat.A Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Recovery Teamof MDC staff, formed in the summer of 2005,developed and carries out the plan, workingwith numerous organizations of the GrasslandsCoalition to carry out recovery efforts. The<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) spearheadedthe formation of the Grasslands Coalitionin 1998, with the <strong>Missouri</strong> departments ofConservation and Natural Resources, The NatureConservancy, Audubon Society chapters andQuail Unlimited as key initial partners.The Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Recovery Planis necessarily ambitious: It calls for establishingseveral 10,000-acre grassland landscapes, basedon a Partners in Flight grassland bird habitatmodel, to support sustainable bird populationsin several locations in western and northern<strong>Missouri</strong>, all within Grasslands Coalition FocusAreas and associated Grassland ConservationOpportunity Areas. Each 10,000-acre area wouldcontain a nearly contiguous core of at least 2,000acres of high quality grassland that could includenative, restored or constructed prairie. Aroundthese core acres would be a matrix of scatteredtracts totaling an additional 2,000 acres of highquality grasslands, at least half of which are 100acres or more in size. The remaining 6,000 acreswithin these landscapes could include croplandor more intensively grazed pasture in a grasslandlandscape.Year in ReviewMDC Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Census Summary (2005-<strong>2007</strong>)<strong>Number</strong> of Male Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-ChickensFocus Area 2005 2006 <strong>2007</strong>Green RidgeHi LonesomeStony Point/Horse CreekGolden/Dorris Creek <strong>Prairie</strong>Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong>El Dorado <strong>Prairie</strong>s68583190Grand River Grasslands (Pawnee <strong>Prairie</strong>) 61 23 17Mystic 13 6 9<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park/Shawnee Trails 14 1 3outside focus area boundaries 34 26 14Statewide 216 109 98<strong>Number</strong> of Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken LeksFocus Area 2005 2006 <strong>2007</strong>Green RidgeHi LonesomeStony Point/Horse CreekGolden/Dorris Creek <strong>Prairie</strong>Taberville <strong>Prairie</strong>El Dorado <strong>Prairie</strong>s1114240Grand River Grasslands (Pawnee <strong>Prairie</strong>) 4 2 1Mystic 2 1 2<strong>Prairie</strong> State Park/Shawnee Trails 2 1 1outside focus area boundaries 12 9 3Statewide 42 26 224231214011812031350160119040NOppadol Paothong26

The information below and on the following pages summarizes the significant progress made on the planduring fiscal year <strong>2007</strong> (July 2006 through June <strong>2007</strong>), taken from the FY07 Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken RecoveryAccomplishments report compiled by Recovery Team Leader and MPF Technical Advisor Max Alleger.New Funding SecuredGrassland and prairie-chicken conservationpriorities attracted $2.5 million to GrasslandsCoalition Focus Areas (GCFAs). This totalincludes:• Fourteen grants from federal, state and privatesources totaling $807,000 to GrasslandsCoalition partners.• <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation(MDC) used $475,000 from federal WildlifeDiversity Funds (WDF) for prairie-chickenrecovery.• Coalition Partners tapped into another$160,200 through competitive WDF grants.• MDC staff enrolled GCFA landowners inUSDA programs worth $377,000. Theseprograms include the Wildlife HabitatIncentives Program (WHIP) and theEnvironmental Quality Incentives Program.• A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service LandownerIncentive Program grant will bring $700,000over three years to GCFAs.<strong>Missouri</strong> Grassland Focus Areas/Conservation Opportunity AreasGrassland ConservationOpportunity AreasGrasslands CoalitionFocus AreasIn 1998, the Grasslands Coalition identified core areas of the state that includedknown prairie-chicken booming grounds, and thus the best places to invest limitedresources to protect and restore grassland habitat. These Grasslands Coalition FocusAreas are now included or associated with Grassland Conservation Opportunity Areas(COAs), areas designated by the <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation in 2005 as partof <strong>Missouri</strong>’s Comprehensive Wildlife Strategy. They remain the best places in thestate to conserve prairie wildlife, to prevent the federal listing of any more plants oranimals as threatened or endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. For a moredetailed map of COAs, see page 4.

Photos Emily HOrner<strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Conservation (MDC)staff worked withNature Conservancystaff to harvest and mixmore than 500 poundsof native prairie seed,which was then plantedon <strong>28</strong>2 acres of MDC andpartner-owned lands.This magnetic pictureframe is one ofseveral promotionalitems created by the<strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Conservation anddistributed in andaround Focus Areas, toreach landowner andyouth audiences.New Habitats Protected within<strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken GCFAs• Grasslands Coalition partners purchased 492acres and protected 400 more acres througheasements or land exchanges.• Existing long-term agreements protected1,740 acres of quality grassland habitats.• New USDA contracts will improve and protect1,800 additional acres for years to come.More Intensive Management of Public andPrivate Grasslands• More than 600 acres of fescue or croplandwere converted to beneficial grasses.• 4,700 acres were treated to control sericealespedeza and other invasive plants.• MDC crews burned more than 4,000 acresof public land.• More than seven miles of hedgerow wereremoved to reopen fragmented grasslands.• Scattered trees within fields were removedfrom 904 acres of public and private land.• 500 pounds of native seed were harvested toplant <strong>28</strong>2 acres of reconstructed prairie.• Patch-burn grazing and other grazingrotations improved brood-rearing habitaton 3,322 acres of MDC prairies. Newlyinstalled hydrants and fences will allow1,000 more acres of public land to be grazedbeginning next year.• Patch-burn or other wildlife-friendly grazingrotations were implemented on 1,500 privatelyowned acres within Focus Areas.<strong>28</strong>

New Partnerships Forged• Audubon <strong>Missouri</strong>, the City of Cole Campand MDC joined forces to hire a termemployee to lead community-based conservationefforts in the Hi Lonesome GCFA,which is adjacent to Cole Camp. City officialsrecognize the ecotourism potential oftheir surrounding native grasslands and areinvesting in prairie-chicken habitat to benefitthe community.• The Conservation Federation of <strong>Missouri</strong>adopted a resolution supporting prairiechickenrecovery and grassland managementefforts.• The <strong>Missouri</strong> Natural ResourcesConservation Service changed existingprograms to more strongly support prairiechickenrecovery efforts.• The Southwest and Osage Valley ResourceConservation and Development Councilsbecame engaged in grassland conservationefforts.• The Audubon Society of <strong>Missouri</strong> joinedthe Coalition and pledged $7,600 towardwork with the <strong>Missouri</strong> Bird ConservationInitiative and the Sac-Osage Rural ElectricCooperative to install raptor exclusions onpower poles near prairie-chicken leks.• Coalition representatives are working withCommercial Agriculture Program economiststo identify affordable ways for farmersto help prairie-chickens, quail and othergrassland birds.In fiscal year <strong>2007</strong>, <strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation (MDC) crews used an herbicidewick (before, upper photo) to successfully treat invasive woody plants (after,lower photo) on more than 200 aces of native prairie with minimal impact to sensitiveforbs. More than 4,500 acres of MDC and partner-owned land was “spot-treated”to control sericea lespedeza, woody sprouts and other invasive plants.Korey Wolfe, at right,visits a native prairiewith a landowner. Koreywas hired as Audubon<strong>Missouri</strong>’s Director ofGrassland Conservationat Cole Camp througha five-year cooperativeagreement involvingthe City of Cole Camp,Audubon <strong>Missouri</strong> andthe <strong>Missouri</strong> Departmentof Conservation.Photos Steve Cooper29

<strong>Fall</strong> MPF Board Meeting andDevelopment NewsSampson’s snakeroot(Orbexilumpedunculatum).Illustration courtesyof Ill. Dept. of NaturalResources.On a cold Saturday morning, October 13, the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) boardbegan its fall meeting at Runge <strong>Prairie</strong> inAdair County. After less than an hour, it was timeto get warm.Brief tours of nearby prairies owned by boardmember Tom Noyes and <strong>2007</strong> MPF <strong>Prairie</strong>Landowners of the Year, Joshua and VondaShoop, were quickly followed by hospitality andhomemade deer chili at the home of Frank andJudy Oberle, who were named 2006 volunteersof the year at the 40th anniversary meeting atCuivre River State Park in October 2006.“Kirksville has similar weather to DesMoines, Iowa,” said Judy Oberle, “and sometimespeople are caught off guard by the cold.” It wasthe light rain and constant prairie wind that madethe search for shelter more pressing.Key items discussed at the brief boardmeeting were the dates and locations for all boardmeetings in 2008 (see the calendar of events onpage 34 for more information), the financialsituation of MPF and the officers for 2008. Inaddition, MPF bestowed awards to Joshua andVonda Shoop and Steve Clubine.Debt Free and Building an EndowmentWith the completion of the Coyne <strong>Prairie</strong>acquisition campaign (see page 36 for details) andthe recent closing of several Grassland ReserveProgram permanent conservation easements,the MPF board has made several importantfinancial decisions. As you read this, MPF willhave paid off all outstanding debt from previousprairie acquisitions and has begun an endowmentaccount at the Community <strong>Foundation</strong> of theOzarks (CFO).Because of CFO’s Stewardship Ozarkscampaign, the first $50,000 that MPF was able toplace into a permanent prairie land managementendowment was matched with $50,000 fromCFO donors. Board members are exploring othergrant and private funding sources to eventuallybuild an endowment sufficient to permanentlycare for the more than 2,500 acres owned byMPF.MPF Officers for 2008The MPF board voted to retain its officersfor 2008 with a few important changes. VicePresident Galen Hasler has moved to Wisconsinand will not be able to fill the traditional dutiesof the vice president, which is essentially apresident-in-training role. Board treasurerPaul Cox was asked to hold the position ofvice president for 2008. Due to his financialbackground, Cox will also do most of the dutiesof the treasurer position. To keep its slate ofofficers, also known as the Executive Committee,at a total of five, a new temporary officer position,Assistant to the Executive Board, was authorizedand will be filled shortly. The current officers areas follows: President Steve Mowry of Trimble,Vice President and Treasurer Paul Cox of KansasCity, Immediate Past President Wayne Mortonof Osceola, Secretary Bruce Schuette of Troy,and Assistant to the Executive Board, vacant atthis time.Justin Johnson, executive director of the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>Justin JohnsonJustin Johnson30

Annual Award WinnersBestowed by the MPF Board of DirectorsMax AllegerFrank OberleJustin JohnsonJustin JohnsonLandowners of the Year: Joshua and Vonda ShoopWhen Vonda Shoop inherited her father’s farm 15 years ago, she and her husband Joshuabecame the owners of around 100 acres of what has been described as “super high quality”prairie.Unlike most of the surrounding land in the cattle country of Adair County in northeastern<strong>Missouri</strong>, the Shoop’s tract had never been plowed and planted with fescue or becomeovergrown with cedar trees. Vonda’s father, George F. Niece, who purchased the land in 1957,had always hayed the tract. “He never wanted it plowed,” said Vonda, “and we chose to honorhis wishes.”When MPF member Frank Oberle, who owns a neighboring farm, suggested that theShoops consider returning their prairie to its full beauty by ending the haying operation anddoing a prescribed burn, they responded enthusiastically. Haying was stopped last year, andMPF professionals and volunteers will do the first burn before the end of this year.“Thanks to the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> and Frank Oberle, the prairie my father lovedwill be filled with even more flowers and wildlife in the future,” said Vonda.According to Oberle, “Josh and Vonda are true stewards of their land. They understandthe importance of preserving prairie for future generations. And, they have become real prairieenthusiasts, too.”Lee Phillion, <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> board memberMPF board member Doris Sherrick of Peculiar, Mo.,was named MPF volunteer of the year in 2006,and claimed her award at the fall <strong>2007</strong> meeting.<strong>Prairie</strong> Professional of the Year:Steve ClubineIt is difficult to think of an aspect of prairie protection andrestoration in <strong>Missouri</strong> where <strong>Prairie</strong> Wildlife Biologist SteveClubine is not deeply involved. A 30-year employee of the<strong>Missouri</strong> Department of Conservation (MDC), Steve is a keymember of the Greater <strong>Prairie</strong>-Chicken Restoration team,and he is the recognized leader in the effort to restore bothfire and grazing to the prairie landscape.Through an agreement with MDC, Steve has taken thelead in managing the 160-acre tract that the <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong><strong>Foundation</strong> (MPF) owns near the town of Green Ridge, alongwith other MDC staff. Clubine assisted MPF’s Justin Johnsonin enrolling the Green Ridge property, sometimes called theBruns Tract, in the Conservation Reserve Program. He thenarranged for the planting and early establishment of the mixof native warm-season grasses and forbs at the site.Steve, a member of MDC’s Private Land ServicesDivision, provides important on-the-ground advice to prairielandowners throughout the state and assists researchscientists at the MDC Grassland Field Station in Clinton asthey study the effects of patch-burn grazing on native andreconstructed prairie as well as treatments to contain sericealespedeza. For more on Steve’s career, see page 38.Justin Johnson, executive director of the<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>31

Visit An MPF <strong>Prairie</strong>•Runge <strong>Prairie</strong><strong>Prairie</strong> Fork ExpansionBruns TractFriendly <strong>Prairie</strong>Drovers <strong>Prairie</strong>Kansas City*•••St. Louis*Schwartz <strong>Prairie</strong>Stilwell <strong>Prairie</strong>Gay Feather <strong>Prairie</strong>Lattner <strong>Prairie</strong>Edgar & RuthDenison <strong>Prairie</strong>Coyne <strong>Prairie</strong>••••• • •*SpringfieldGolden <strong>Prairie</strong>Penn-Sylvania <strong>Prairie</strong>La Petite Gemme <strong>Prairie</strong>ImperviousHigh Density UrbanLow Density UrbanBarren or Sparsely VegetatedCroplandGrassland (native and non-native)Deciduous ForestEvergreen ForestMixed ForestDeciduous Woody/HerbaceousEvergreen Woody/HerbaceousWoody Dominated WetlandHerbaceous Dominated WetlandOpen water<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> prairie properties range in size from 37 acres to more than 1,000.Members are welcome to visit these prairies, which they help support, at any time. For information about and directions to MPF prairies,visit www.moprairie.org or call 573-356-78<strong>28</strong>.Map credit: MoRAP, <strong>Missouri</strong> Resource Assessment Partnership32

Richard’s <strong>Prairie</strong> Management AdviceLate <strong>Fall</strong> and Winter ChoresThe following prairie management advice from previous issues of the Journal is reprintedhere to help those of you preparing to improve your grasslands during the colder months ofthe year. The dormant season is a good time to remove woody growth and plant seed.Cutting TreesThe most important thing to remember when cutting trees is that you must treat the cutstumps with some sort of herbicide. Untreated stumps tend to multiply, and it is well worthyour time to treat all the stumps as you go. At the end of a long day, you’ll never find them all.I use undiluted Tordon RTU, which is Picloram and 2,4-D, or a Crossbow and diesel mix (5%Crossbow and 95% diesel). Crossbow is triclopyr plus 2,4-D.If using Tordon RTU, which stands for Ready to Use, apply the herbicide directly to thecambium layer of the cut stump. The cambium is the ring just inside the bark. I use a wipingaction to treat stumps this way, with the Tordon RTU in an applicator bottle with a permeabletop. If using the Crossbow and diesel mix, spray the top of the stump and down the sides tothe ground. Small trees and brush of 2” diameter or less can be killed without cutting via aprocess called basal bark treatment. Spray the stem all the way around, about 24” high. Asalways, follow all herbicide label instructions for safety and protection of your resources. Forinstance, neither Tordon RTU nor the Crossbow mix should be used around water, as 2,4-Dhas been shown to greatly harm desirable aquatic species.Winter Seeding of Native Grasses and ForbsIf you have sprayed and burned your tall fescue or other unwanted exotic species to prepareyour seed bed by the winter, I recommend broadcast planting your native prairie grasses andforb seed in December or the first week of January. A common mistake in native plantings isseeding your expensive prairie species too deep, so let Mother Nature do most of the work.You can use a harrow to rough up the surface and a culti-packer after the seed has beenbroadcast to insure seed to soil contact. The freezing and thawing action over the wintershould work the seed to the proper depth.Resources Available OnlineAdditional advice regarding winter seeding of native prairie species is available at severalWeb sites. Here are a few to start with:Carol Davithttp://www.hamiltonseed.com/Hamilton_Started.htmlhttp://www.mowildflowers.net/growinginfo/seeding.htmlhttp://www.pureairseed.com/wst_page7.htmlTo find a wide variety of native seed sources, visit www.grownative.org and exploretheir Buyer’s Guide section. If you do not have access to the Internet, contact MPF at1-888-843-6739 for advice.Operations Manager Richard Datemahas been managing MPF prairies since being hiredas the first full-time employee of MPF in1998.He and his wife Mia live in Springfield with their four children.As always, please send questions aboutprairie management to missouriprairie@yahoo.com, and Richard will do his bestto answer your questions right away. Someresponses may be used in a future issue ofthe Journal. To see past land managementcolumns, visit www.moprairie.org .33

Calendar of <strong>Prairie</strong>-Related Events2008 <strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>Board MeetingsSave the dates! All members are invitedto attend these meetings. More information willbe made available in future issues of the Journaland at www.moprairie.org.February 2, 2008 Board Meeting at <strong>Prairie</strong>Fork Conservation Area in Williamsburg, Mo. Dueto adverse field conditions, no public activitiesare planned in association with this wintermeeting, but members are welcome to attend.If interested, RSVP to Justin Johnson at 573-356-78<strong>28</strong>. For more information about <strong>Prairie</strong>Fork Conservation Area, visit http://prairiefork.missouri.edu/May 24–26, 2008 (Memorial Day Weekend)Board Meeting and <strong>Prairie</strong> Days at Schwartz<strong>Prairie</strong> in St. Clair County. At least two full days ofactivities are being planned.July 26, 2008 Board Meeting and <strong>Prairie</strong> Dayat <strong>Prairie</strong> View, a private prairie near the town ofRich Hill. Join MPF board member Bonnie Teel asshe opens her private property, approximately1,000 acres, for a public prairie field day.October 11, 2008 Annual Meeting and<strong>Prairie</strong> Day at Hamilton’s Native Outpost in TexasCounty. MPF officers will be selected, awards willbe presented and a tour of the Hamilton’s seedbusiness will be given, among other activities.<strong>Missouri</strong> <strong>Prairie</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong>member Frank Oberle took thesewinter grassland photographs innorthern <strong>Missouri</strong>.34