MR. JUSTICE ABDUL HAMEED DOGAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE FAQIR ...

MR. JUSTICE ABDUL HAMEED DOGAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE FAQIR ...

MR. JUSTICE ABDUL HAMEED DOGAR, HCJ MR. JUSTICE FAQIR ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

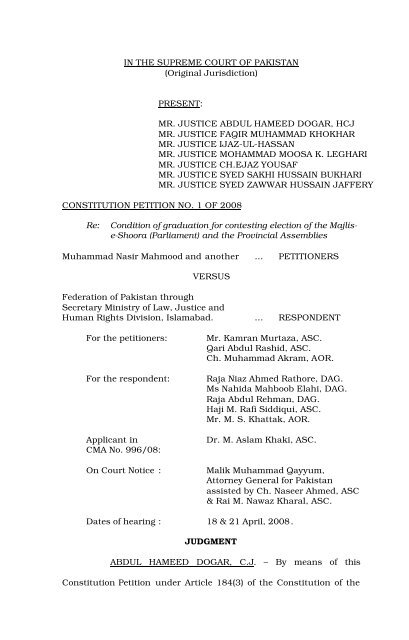

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN<br />

(Original Jurisdiction)<br />

PRESENT:<br />

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> <strong>ABDUL</strong> <strong>HAMEED</strong> <strong>DOGAR</strong>, <strong>HCJ</strong><br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> <strong>FAQIR</strong> MUHAMMAD KHOKHAR<br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> IJAZ-UL-HASSAN<br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> MOHAMMAD MOOSA K. LEGHARI<br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> CH.EJAZ YOUSAF<br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> SYED SAKHI HUSSAIN BUKHARI<br />

<strong>MR</strong>. <strong>JUSTICE</strong> SYED ZAWWAR HUSSAIN JAFFERY<br />

Re:<br />

Condition of graduation for contesting election of the Majlise-Shoora<br />

(Parliament) and the Provincial Assemblies<br />

Muhammad Nasir Mahmood and another … PETITIONERS<br />

VERSUS<br />

Federation of Pakistan through<br />

Secretary Ministry of Law, Justice and<br />

Human Rights Division, Islamabad. … RESPONDENT<br />

For the petitioners:<br />

For the respondent:<br />

Applicant in<br />

CMA No. 996/08:<br />

On Court Notice :<br />

Mr. Kamran Murtaza, ASC.<br />

Qari Abdul Rashid, ASC.<br />

Ch. Muhammad Akram, AOR.<br />

Raja Niaz Ahmed Rathore, DAG.<br />

Ms Nahida Mahboob Elahi, DAG.<br />

Raja Abdul Rehman, DAG.<br />

Haji M. Rafi Siddiqui, ASC.<br />

Mr. M. S. Khattak, AOR.<br />

Dr. M. Aslam Khaki, ASC.<br />

Malik Muhammad Qayyum,<br />

Attorney General for Pakistan<br />

assisted by Ch. Naseer Ahmed, ASC<br />

& Rai M. Nawaz Kharal, ASC.<br />

Dates of hearing : 18 & 21 April, 2008.<br />

JUDGMENT<br />

<strong>ABDUL</strong> <strong>HAMEED</strong> <strong>DOGAR</strong>, C.J. – By means of this<br />

Constitution Petition under Article 184(3) of the Constitution of the

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 2<br />

Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 (the Constitution), the petitioners<br />

have called in question the validity of the provisions of Article 8-A of<br />

the Conduct of General Election Order, 2002 (Chief Executive’s Order<br />

No. 7 of 2002) and clause (cc) of subsection (1) of section 99 of the<br />

Representation of the People Act, 1976, on the touchstone of Articles<br />

17 and 25 of the Constitution. The impugned provisions laid down<br />

that a person would not be qualified to be elected or chosen as a<br />

member of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) or a Provincial Assembly<br />

unless he was at least a graduate possessing a bachelor degree in any<br />

discipline or any degree recognized as equivalent by the University<br />

Grants Commission under the University Grants Commission Act,<br />

1974, or any other law for the time being in force.<br />

CMA No.996/2008<br />

2. During the course of proceedings, Dr. M. Aslam Khaki,<br />

ASC filed Civil Miscellaneous Application No. 996 of 2008 for his<br />

impleadment as a respondent/party to the above Constitution<br />

Petition on the ground that he would support the impugned<br />

provisions of law laying down the qualification of being a graduate to<br />

contest election to the Parliament and the Provincial Assemblies. He<br />

submitted that previously he had filed the Deeni Madaras Certificates<br />

Equivalence case as pro bono publico. Since the present Constitution<br />

Petition involved a question of general public importance and he<br />

being a public spirited person, he prayed that he may be allowed to<br />

address the Court. The learned Attorney General for Pakistan and Mr.<br />

Kamran Murtaza did not oppose the application. Therefore, Mr. Khaki

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 3<br />

was allowed to address the Court on the issues involved in the<br />

present Constitution Petition.<br />

3. The case of the petitioners is that they are the citizens of<br />

Pakistan and by the promulgation of Article 8-A of the Conduct of<br />

General Election Order, 2002 and clause (cc) of subsection (1) of<br />

section 99 of the Representation of the People Act, 1976 they have<br />

been deprived of their Fundamental right to contest election and to<br />

form government as interpreted by this Court in various judgments as<br />

a natural corollary of the right to form or be a member of a political<br />

party guaranteed under Article 17(2) of the Constitution. The learned<br />

counsel for the petitioners has made the following submissions: -<br />

(1) The fundamental right enshrined in Article 17 of the<br />

Constitution is subject to “any reasonable restrictions<br />

imposed by law in the interest of the sovereignty or<br />

integrity of Pakistan or public order,” but the condition of<br />

graduation qualification for contesting election does not<br />

fall within the ambit of the above controlling clause<br />

inasmuch as the said qualification cannot be said to have<br />

been imposed in the interest of the “sovereignty or<br />

integrity of Pakistan, public order or morality.”<br />

(2) By laying down the qualification in terms of education, an<br />

elitist class has been created. The acquisition of education<br />

is directly related to, and dependent upon the prevailing<br />

conditions in which a person may find himself. Thus,<br />

educational qualification for contesting election<br />

constitutes discrimination, which is prohibited under<br />

Article 25 of the Constitution and is, therefore, liable to be<br />

struck down.<br />

(3) The impugned qualification is not a reasonable<br />

classification within the scope of Article 25 as interpreted<br />

in I.A. Sharwani’s case (1991 SC<strong>MR</strong> 1041).

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 4<br />

(4) The condition of graduation was meant only for the<br />

General Election, 2002 and was not to apply to the future<br />

elections, which was apparent from the title of the statute<br />

itself, viz., “the Conduct of General Election Order, 2002”<br />

and was further fortified from the statement given below<br />

the title of the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 to the<br />

effect that “An order to provide for the conduct of General<br />

Elections 2002” and the recitals contained in Articles 3<br />

and 4, e.g., “The provisions of this Order shall have effect<br />

notwithstanding anything contained in the Constitution or<br />

in any other law for the time being in force relating to the<br />

forthcoming elections to the Senate, National Assembly and<br />

the Provincial Assemblies” and “……….. the Election<br />

Commission shall take such steps and measures,<br />

including preparation of electoral rolls and delimitation of<br />

the constituencies, and adopt such procedure, do such<br />

acts, pass such orders, issue such directions and take all<br />

such ancillary, incidental and consequential steps as may<br />

be deemed necessary for effectively carrying out the<br />

elections for the members of the Senate, National Assembly<br />

and Provincial Assemblies in October 2002”.<br />

(5) The primary objective of the impugned legislation was to<br />

debar certain persons from contesting General Election of<br />

2002. In this behalf, reference was made to the text of the<br />

original Conduct of General Election Order 2002 which<br />

did not prescribe any educational qualification for<br />

contesting the election. The said Order was subsequently<br />

amended by insertion of Article 8-A, which provided that a<br />

person would not be eligible to contest election if he was<br />

not a graduate.<br />

(6) The Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 has been<br />

included in the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution (Serial<br />

No.32). Therefore, the National Assembly is precluded<br />

from making legislation on the subject without the<br />

previous sanction of the President.

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 5<br />

(7) No reason whatsoever was mentioned to include the<br />

impugned legislation in the Sixth Schedule and thus equal<br />

protection of law was not available to those who were not<br />

graduates.<br />

(8) The provisions of Article 8-A were earlier challenged before<br />

this Court in Constitution Petitions No. 29 to 33 of 2002,<br />

but the same were dismissed through the judgment in the<br />

case of Pakistan Muslim League (Q) v. Chief Executive of<br />

the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (PLD 2002 SC 994),<br />

hereinafter referred to as the PML (Q)’s case.<br />

(9) In the PML (Q)’s case, question of validity of the impugned<br />

provisions of the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002<br />

was not examined on the touchstone of the Constitution<br />

and the Court dilated upon circumstances which had little<br />

bearing on the controversy before it.<br />

(10) The judgment in the PML (Q)’s case was rendered without<br />

proper assistance. Even elementary data was not<br />

produced regarding the literacy rate of the country, the<br />

number of graduates in different provinces, particularly in<br />

the rural areas and far-flung areas like Chaghi in the<br />

Province of Balochistan and other similar parts of the<br />

country where the vast majority of the population was not<br />

having even matriculation, middle or primary level<br />

education. Therefore, the same was required to be<br />

revisited and overruled.<br />

4. Dr. M. Aslam Khaki, ASC submitted that the following<br />

issues needed to be dilated upon: -<br />

(1) Whether the impugned law is an ordinary law or a<br />

law protected by the Constitution?<br />

(2) Whether this Court has jurisdiction to<br />

examine/scrutinize the validity of the constitutional<br />

provisions?

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 6<br />

(3) Whether the instant petition is mala fide to serve the<br />

purpose of one or few persons and not the public at<br />

large?<br />

(4) Whether the petition is hit by the principle of res<br />

judicata and estoppel?<br />

(5) Whether the impugned legislative measures are<br />

offensive to the provisions of the Constitution?<br />

(6) Whether the requirement of graduation for<br />

contesting parliamentary elections is reasonable and<br />

in public interest?<br />

(7) Whether different treatment of the citizens on their<br />

unequal circumstances is a discrimination, or a<br />

distinction?<br />

(8) Whether after the conceding statement of the Federal<br />

Government about the badness of the impugned law,<br />

will it not be appropriate to direct the petitioners to<br />

seek amendment of the law?<br />

(9) Whether the petition is liable to be dismissed or at<br />

least amended for not impleading the necessary<br />

parties like the Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs, the<br />

President of Pakistan and members of the<br />

Parliament who would be adversely affected?<br />

5. Raja Niaz Ahmad Rathore, learned Deputy Attorney<br />

General appearing for the respondent Federation of Pakistan<br />

submitted that in the context of the present case this Court was to<br />

see as to whether the impugned legislation was not a reasonable<br />

restriction within the meaning of Article 17 of the Constitution. He<br />

contended that the impugned Article 8-A of the Chief Executive’s<br />

Order No. 7 of 2002 was a bad law and ultra vires the Constitution<br />

and was required to be struck down by this Court.

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 7<br />

6. Malik Muhammad Qayyum, learned Attorney General for<br />

Pakistan appeared in the matter on Court’s call. He presented his<br />

viewpoint as under: -<br />

i) There are two types of questions, one is political and<br />

the other is legal or constitutional. Whether the<br />

government will like to repeal the impugned<br />

legislation is a political decision, but whether the law<br />

is ultra vires, is to be decided by this Court.<br />

ii) The Supreme Court is not bound by its earlier<br />

rulings. It has the power and jurisdiction to overrule<br />

its previous judgments. In Perdeep Kumar Biswas v.<br />

Indian Institute of Chemical Biology (2002) 5 Supreme<br />

Court Cases 111), the Supreme Court of India<br />

overruled its earlier judgment. If this Court comes to<br />

the conclusion that the judgment in PML (Q)’s case<br />

was erroneous, there is no reason to perpetuate a<br />

wrong or a mistake. The judgment in PML (Q)’s case<br />

does not take notice of the real issues involved<br />

therein. It is mentioned in Para. 22 of the judgment<br />

that necessary data has not been supplied. The<br />

Court did not go into the question of reasonableness<br />

or otherwise of the impugned law on the touchstone<br />

of the Constitution.<br />

iii) Right to contest election is a fundamental right and<br />

every body should be encouraged for the enforcement<br />

of the fundamental rights.<br />

iv) The impugned educational qualification is partly a<br />

bad law. However, to say that a law is bad, motive is<br />

required to be attributed.<br />

v) The requirement of graduation qualification in the<br />

matter of election is a negation of the democracy. It is<br />

against the concept of political justice guaranteed in<br />

the Objectives Resolution and Preamble of the<br />

Constitution.

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 8<br />

vi) The Objectives Resolution, which is now a<br />

vii)<br />

substantive part of the Constitution by means of<br />

Article 2A, inter alia, provides:-<br />

“Whereas sovereignty over the entire Universe<br />

belongs to Almighty Allah alone, and the<br />

authority to be exercised by the people by<br />

Pakistan within the limits prescribed by Him is<br />

a sacred trust;<br />

And whereas it is the will of the people of<br />

Pakistan to establish an order;<br />

Wherein the State shall exercise its powers and<br />

authority through the chosen representatives of<br />

the people;<br />

………………….<br />

Wherein shall be guaranteed fundamental<br />

rights, including equality of status, of<br />

opportunity and before law, social, economic<br />

and political justice, and freedom of thought,<br />

expression, belief, faith, worship and<br />

association, subject to law and public morality.”<br />

A democracy is a government of the people, by the<br />

people and for the people. The requirement of<br />

educational qualification creates a separate class.<br />

Therefore, it cannot be said that such a government<br />

is a government of the people. In modern laws the<br />

trend is that a preamble need not be there because<br />

the preamble states only the object or the intent of<br />

the legislature.<br />

viii) The impugned law creates an elitist democracy<br />

amounting to discrimination, which is forbidden<br />

under Article 25 of the Constitution. The Advanced<br />

Law Lexicon, The Encyclopaedic Law Dictionary, 3 rd<br />

Edition, Volume 2 (2005) defines democracy as<br />

under:-<br />

“One of the three forms of government; that in<br />

which the sovereign power is neither lodged in<br />

one man, as in a monarchy, nor in the nobles,

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 9<br />

ix)<br />

as in an oligarchy, but in the collective body of<br />

the people; government by the people; state in<br />

which such a government prevails; the principle<br />

that all citizens have equal political rights.”<br />

The impugned graduation qualification does not meet<br />

the test of reasonableness. The graduation<br />

qualification requires 14 years’ studies. If a person<br />

studies for 13 years and is not a graduate, no<br />

weightage will be given to 13 years’ learning. In a<br />

democratic set up the emphasis is on social,<br />

economic and political justice. In PML(Q)’s case, the<br />

Court did not consider the data relating to the<br />

literacy rate of the population or the question such<br />

as how many graduates were there in backward<br />

areas, such as Chaghi, etc. ?<br />

x) The impugned law prescribes simple graduation<br />

qualification for contesting election and there is no<br />

particular requirement in what discipline the person<br />

should be a graduate. A science graduate, e.g. a<br />

person holding B.Sc. degree is eligible to participate<br />

in the election. Will such a person be competent to<br />

frame law? Graduation is 14 years’ education in any<br />

discipline, though the main function of the members<br />

of the Parliament or the Provincial Assemblies is to<br />

legislate laws.<br />

7. To begin with, we may deal with the objection raised by<br />

Mr. Khaki that the instant petition was hit by the principles of res<br />

judicata and estoppel. He submitted that the issue had already been<br />

decided in the PML (Q)’s case and the only course open to the<br />

petitioners was to file a review petition. Even otherwise, the present<br />

petition suffered from laches. The PML(Q)’s case was decided on<br />

11.7.2002 whereas the election under the Chief Executive’s Order No.

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 10<br />

7 of 2002 was held in November 2002. In the alternative, the<br />

petitioners could approach the Parliament for amendment of the law.<br />

In another formulation Mr. Khaki contended that the Chief<br />

Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 was not an ordinary law, but had<br />

been protected under the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution, which<br />

could not be amended or repealed without prior sanction of the<br />

President. According to Mr. Khaki, the Mutahidda Mujlis-e-Amal<br />

(MMA) had agreed to pass the Constitution (Seventeenth Amendment)<br />

Act, 2003 on the condition that the retirement age of the Judges of<br />

the Superior Courts, as enhanced under the Legal Framework Order,<br />

2002 was reduced and the original position in that regard was<br />

restored. He canvassed the view that after the Seventeenth<br />

Constitutional Amendment, the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002<br />

had become part of the Constitution and could only be amended in<br />

the manner provided for amendment of the Constitution. He<br />

submitted that the Parliament had the power to amend the<br />

Constitution but this Court did not have such a power, as it was to<br />

interpret the Constitution. He contended that Article 270AA of the<br />

Constitution provided, inter alia, that all laws made between the 12 th<br />

October 99 and the date on which other Articles came into force, i.e.<br />

31 st December 2003 (both inclusive) were competently made and that<br />

under Article 268 of the Constitution all existing laws would continue<br />

in force until altered, repealed or amended by the appropriate<br />

legislature. For facility of reference, Article 270AA of the Constitution<br />

is reproduced below: -<br />

“270AA. Validation and affirmation of laws etc.-

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 11<br />

(1) The Proclamation of Emergency of the fourteenth<br />

day of October, 1999, all President’s Orders,<br />

Ordinances, Chief Executive’s Orders, including the<br />

Provisional Constitution Order No. 1 of 1999, the<br />

Oath of Office (Judges) Order, 2000 (No.1 of 2000),<br />

Chief Executive’s Order No. 12 of 2002, the<br />

amendments made in the Constitution through the<br />

Legal Framework Order, 2002 (Amendment) Order,<br />

2002 (Chief Executive’s Order No. 29 of 2002), the<br />

Legal Framework (Second Amendment) order, 2002<br />

(Chief Executive’s Order No.32 of 2002) and all<br />

other laws made between the twelfth day of<br />

October, one thousand nine hundred and ninetynine<br />

and the date on which this Article comes into<br />

force (both days inclusive), having been duly made<br />

are accordingly affirmed, adopted and declared to<br />

have been validly made by the competent authority<br />

and notwithstanding anything contained in the<br />

Constitution shall not be called in question in any<br />

court or forum on any ground whatsoever.<br />

(2) All orders made, proceedings taken, appointments<br />

made, including secondments and deputations, and<br />

acts done by any authority, or by any person, which<br />

were made, taken or done, or purported to have<br />

been made, taken or done, between the twelfth day<br />

of October, one thousand nine hundred and ninetynine,<br />

and the date on which this Article comes into<br />

force (both days inclusive), in exercise of the powers<br />

derived from any Proclamation, President’s Orders,<br />

Ordinances, Chief Executive’s Orders, enactments,<br />

including amendments in the Constitution,<br />

notifications, rules, orders, bye-laws, or in<br />

execution of or in compliance with any orders made<br />

or sentences passed by any authority in the<br />

exercise or purported exercise of powers as<br />

aforesaid, shall, notwithstanding any judgment of<br />

any court, be deemed to be and always to have been<br />

validly made, taken or done and shall not be called<br />

in question in any court or forum on any ground<br />

whatsoever.<br />

(3) All proclamations, President’s Orders, Ordinances,<br />

Chief Executive’s Orders, laws, regulations,<br />

enactments, including amendments in the<br />

Constitution, notifications, rules, orders or bye-laws<br />

in force immediately before the date on which this<br />

Article comes into force shall continue in force until<br />

altered, repealed or amended by the competent<br />

authority.<br />

Explanation.- In this clause, “competent authority”<br />

means,-

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 12<br />

a) in respect of Presidents’ Orders, Ordinances,<br />

Chief Executive’s Orders and enactments,<br />

including amendments in the Constitution,<br />

the appropriate Legislature; and<br />

b) in respect of notifications, rules, orders and<br />

bye-laws, the authority in which the power to<br />

make, alter, repeal or amend the same vests<br />

under the law.<br />

4) No suit, prosecution or other legal proceedings,<br />

including writ petitions, shall lie in any court or<br />

forum against any authority or any person, for or<br />

on account of or in respect of any order made,<br />

proceedings taken or act done whether in the<br />

exercise or purported exercise of the powers<br />

referred to in clause (2) or in execution of or in<br />

compliance with orders made or sentences passed<br />

in exercise or purported exercise of such powers.<br />

5) For the purposes of clauses (1), (2) and (4), all<br />

orders made, proceedings taken, appointments<br />

made, including secondments and deputations, acts<br />

done or purporting to be made, taken or done by<br />

any authority or person shall be deemed to have<br />

been made, taken or done in good faith and for the<br />

purpose intended to be served thereby.”<br />

8. A bare perusal of Article 270AA shows that all the<br />

legislative measures including the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of<br />

2002 made by the Chief Executive of Pakistan were adopted, affirmed<br />

and declared by the Parliament as having been validly and<br />

competently made. There is no cavil with the proposition that under<br />

Article 268 of the Constitution all existing laws shall continue in force<br />

until altered, repealed or amended by the appropriate legislature or<br />

that the Parliament is not debarred from adding other<br />

conditions/qualifications for being a candidate for membership of<br />

Parliament or, as the case may be, the Provincial Assemblies. Of<br />

course, at the time of its promulgation the Chief Executive’s Order<br />

No. 7 of 2002 was an extra-constitutional document, as the same was<br />

to have effect notwithstanding anything contained in the Constitution

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 13<br />

(e.g. recitals in Articles 3, 4, 8, 8-A, etc.). However, this position was<br />

displaced on revival of the Constitution when it lost its supraconstitutional<br />

character on account of its non-incorporation in any of<br />

the provisions of the Constitution and its having been included in the<br />

Sixth Schedule to the Constitution. The learned Attorney General for<br />

Pakistan rightly pointed out that the impugned law was not one of<br />

those laws, which were included in the First Schedule of the<br />

Constitution and thus saved from the operation of fundamental<br />

rights. Article 8 of the Constitution reads as under: -<br />

“8. - (1) Any law, or any custom or usage having the<br />

force of law, in so far as it is inconsistent with the rights<br />

conferred by this Chapter, shall, to be extent of such<br />

inconsistency, be void.<br />

(2) The State shall not make any law which takes<br />

away or abridges the rights so conferred and any law<br />

made in contravention of this clause shall, to the extent of<br />

such contravention, be void.”<br />

(3) The Provision of this Article shall not apply to-<br />

(a)<br />

any law relating to members of the Armed<br />

Forces, or of the police or of such other<br />

forces as are charged with the<br />

maintenance of public order, for the<br />

purpose of ensuring the proper discharge<br />

of their duties or the maintenance of<br />

discipline among them; or<br />

(b) any of the –<br />

(i)<br />

(ii)<br />

laws specified in the First Schedule<br />

as in force immediately before the<br />

commencing day or as amended by<br />

any of the laws specified in that<br />

Schedule;<br />

other laws specified in Part I of the<br />

First Schedule;<br />

and no such law nor any pro vision thereof shall be<br />

void on the ground that such law or provision is

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 14<br />

inconsistent with, or repugnant to, any provision of<br />

this Chapter.<br />

(4) Notwithstanding anything contained in<br />

paragraph (b) of clause (3), within a period of two<br />

years from the commending day, the appropriate<br />

Legislature shall bring the laws specified in [Part II of<br />

the First Schedule] into conformity with the rights<br />

conferred by the Chapter:<br />

Provided that the appropriate Legislature may<br />

by resolution extend the said period of two years by<br />

a period and exceeding six months.<br />

Explanation. - If in respect of any law Majlis-e-<br />

Shoora (Parliament) is the appropriate Legislature,<br />

such resolution shall be a resolution of the National<br />

Assembly.<br />

(5) The rights conferred by this Chapter shall<br />

not be suspended except as expressly provided by<br />

the Constitution.”<br />

Accordingly, in the post Seventeenth Constitutional Amendment<br />

period, the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 continued on the<br />

statute book as ordinary legislation with the difference that after its<br />

inclusion in the Sixth Schedule, further legislation on it could be<br />

made only after obtaining sanction of the President.<br />

9. The argument of Mr. Khaki would have carried weight had<br />

the educational qualification been added in the list of qualifications<br />

for membership of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) provided for in Article<br />

62 of the Constitution. He frankly conceded that no such amendment<br />

had been made in the said Article. Needless to observe, the Chief<br />

Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 was never made a part of the<br />

Constitution.<br />

10. At this stage, we may deal with the contention of the<br />

learned counsel for the petitioners that it was clear from the various<br />

provisions of the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 that the

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 15<br />

graduation qualification was intended for 2002 elections alone. No<br />

doubt under the law a qualification could be introduced at any time,<br />

but the timing of a particular statute would assume importance and<br />

relevance where the proposed law affected the fundamental rights of<br />

the citizens who, but for the operation of the said law, would be<br />

eligible to contest the election. This aspect of the matter was taken<br />

into consideration while deciding Javed Jabbar v. Federation of<br />

Pakistan (PLD 2003 SC 955), but not in the PML (Q)’s case.<br />

11. It may be noted that Article 8 of the original Chief<br />

Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 (PLD 2002 Central Statutes 193) only<br />

provided that the laws relating to election etc., for the time being in<br />

force, insofar as they were not inconsistent with any provision of the<br />

Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 shall apply and no such<br />

educational qualification was laid down therein for contesting<br />

election. However, by the Conduct of General Elections (Amendment)<br />

Order, 2002, new Article 8-A was inserted into the Chief Executive’s<br />

Order No. 7 of 2002. Article 8-A reads as under:-<br />

“8-A. Notwithstanding anything contained in the<br />

Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973, the<br />

Senate (Election) Act, 1975 (LI of 1975), the<br />

Representation of People Act, 1976 (LXXXV of 1976), or<br />

any other law for the time being in force, a person shall<br />

not be qualified to be elected or chosen as a member of<br />

Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) or a Provincial Assembly<br />

unless he is at least a graduate possessing a bachelor<br />

degree in any discipline or any degree recognized as<br />

equivalent by the University Grants Commission under<br />

the University Grants Commission Act, 1974 or any other<br />

law for the time being in force.”<br />

The Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 was promulgated on<br />

27.2.2002 and Article 8-A was inserted therein on 25.6.2002 whereas<br />

a part of the Constitution was revived on 16.11.2002 and the rest on

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 16<br />

31.12.2003. The judgment in PML(Q)s case was rendered on<br />

11.7.2002. Section 99(1)(c) of the Representation of the People Act,<br />

1976, was introduced on 30.7.2002. Thus, it was after the passing of<br />

the judgment in PML (Q)’s case that an amendment in the<br />

Representation of the People Act, 1976, was made and clause (cc) in<br />

subsection (1) of section 1 added by Ordinance XXXVI of 2002. For<br />

facility of reference, said clause (cc) is reproduced below: -<br />

“(cc) he is at least a graduate, possesses a bachelor’s<br />

degree in any discipline or any degree recognized as<br />

equivalent thereto by the University Grants Commission<br />

under the University Grants Commission Act, 1974 (XXIII<br />

of 1974), or any other law for the time being in force.”<br />

Having been incorporated in the Representation of the People Act,<br />

1976, the said qualification became a part of the law as contemplated<br />

in Article 62 (i) or Article 63 (s) of the Constitution. Therefore, even if<br />

it be assumed that the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002<br />

including the provisions of Article 8-A was meant for the General<br />

Election of 2002, the educational qualification continued in operation<br />

by virtue of clause (cc) in subsection (1) of section 99 ibid with the<br />

result that the provisions of Article 8-A of the Chief Executive’s Order<br />

No. 7 of 2002, as observed earlier, were rendered bereft of their extraconstitutional<br />

character after election 2002, which were to be treated<br />

at par with other sub-constitutional legislation and open to judicial<br />

review on the touchstone of the provisions of the Constitution.<br />

12. Mr. Khaki contended that the Government in power had<br />

overwhelming majority in the Parliament and was in a position to<br />

make amendment in the aforesaid law. In response, the learned<br />

counsel for the petitioners, as also the learned Deputy Attorney

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 17<br />

General submitted that due to the inclusion of the impugned law in<br />

the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution and the requirement of<br />

previous sanction of the President for introducing any legislation in<br />

respect thereof, it was not possible for the Government to make any<br />

legislation on the subject since it was not sure that the President<br />

would accord the requisite sanction as an attempt to amend the law<br />

in the past had failed. We would not like to go into this or other<br />

similar questions and would confine ourselves to the examination of<br />

the legal and constitutional issues arising in the matter. Even<br />

otherwise, the impugned graduation qualification for contesting<br />

election was subjected to scrutiny in PML (Q)’s case and it was<br />

nobody’s case that the same was not open to challenge in the exercise<br />

of power of judicial review by this Court. Rather, in the said case, the<br />

case was examined from a different perspective, which was apparent<br />

from the narration of political process through which Pakistan had<br />

passed since its inception. Having recounted the major political<br />

developments/events, the Court summed up the discussion in Para<br />

19 of the judgment in the following words: -<br />

“19. It was necessary to narrate this history briefly as its<br />

certain parts distinctly point to a political culture, which<br />

leaves much to be desired. It demonstrated utter disregard<br />

for the parliamentary values and deliberate attempt to<br />

inure the soul of democracy. The establishment of a<br />

democratic order and the institutions therein requires<br />

utmost responsibility on the part of the elected<br />

representatives of the people but the record of most of the<br />

elected representatives of the four dissolved National and<br />

Provincial Assemblies speaks volumes about their psyche,<br />

lack of education and sense of responsibility. It also shows<br />

that the political field was dominated by a coterie of<br />

individuals representing a special class of vested interests,<br />

which ensured that if not they, their kith and kin were<br />

elected as members of the Assemblies. Regardless of the<br />

ideal standards, their main effort was directed to have

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 18<br />

their hegemony to the political field. There are known<br />

cases where through manoeuvring and machination one<br />

faction deliberately went to the opposition and the other to<br />

the treasury benches.”<br />

13. Be that as it may, the main issue is whether the present<br />

petition is competent despite the matter having been decided by this<br />

Court in PML (Q)’s case. The learned counsel for the petitioners<br />

submitted that the remedy of review was not available to the<br />

petitioners. The petition involved question of public importance with<br />

reference to enforcement of fundamental rights. There was a<br />

continuing cause of action inasmuch the petitioners and other nongraduate<br />

citizens were debarred from contesting election forever, and<br />

the principles of res judicata, estoppel or laches were not applicable in<br />

such matters. The learned Attorney General for Pakistan submitted<br />

that the Supreme Court was not bound by its earlier rulings and<br />

could overrule its previous judgments. He took us through a<br />

judgment of the Indian Supreme Court reported as Perdeep Kumar<br />

Biswas v. Indian Institute of Chemical Biology (2002) 5 Supreme Court<br />

Cases 111). In the precedent case, the appellants filed a writ petition<br />

before the Calcutta High Court to challenge the termination of their<br />

service by the respondent which was a unit of the Council of<br />

Scientific and Industrial Research (for short “CSIR”). They also sought<br />

an interim order but that was refused by the High Court on the prima<br />

facie view that in view of the Supreme Court’s decision in Sabhajit<br />

Tewary v. Union of India (AIR 1975 SC 1329 = (1975) 1 SCC 485), the<br />

writ petition itself was not maintainable. The appellants approached<br />

the Supreme Court of India. A two-Judge Bench of the Supreme<br />

Court, in view of subsequent decisions, held that Sabhajit Tewary’s

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 19<br />

case required reconsideration. The matter was examined by the<br />

Constitution Bench, which overruled the judgment in Sabhajit<br />

Tewary’s case in the following terms:-<br />

“Although the Court noted that it was the Government<br />

which was taking the “special care” nevertheless the writ<br />

petition was dismissed ostensibly because the Court<br />

factored into its decision two premises:-<br />

i) “The society does not have a statutory character<br />

like the Oil and Natural Gas Commission, or the<br />

Life Insurance Corporation or Industrial Finance<br />

Corporation. It is a Society incorporated in<br />

accordance with the provisions of the Societies<br />

Registration Act” (SCC p. 486, Para 4), and<br />

ii) This Court has held in Praga Tools Corpn. v. C.A.<br />

Imanual Heavy Engg. Mazdoor Union v. State of<br />

Bihar and in S.L. Agarwal (Dr) v. G.M., Hindustan<br />

Steel Ltd. that the Prage Tools Corporation, Heavy<br />

Engineering Mazdoor Union and Hindustan Steel<br />

Ltd. are all companies incorporated under the<br />

Companies Act and the employees of these<br />

companies do not enjoy the protection available to<br />

government servants as contemplated in Article<br />

311. The companies were held in these cases to<br />

have independent existence of the Government and<br />

by the law relating to corporations. These could not<br />

be held to be departments of the Government.”<br />

(SCC p. 487, Para 5)<br />

With respect, we are of the view that both the premises<br />

were not really relevant and in fact contrary to the “voice<br />

and hands” approach in Sukhdev Singh. Besides reliance<br />

by the Court on decisions pertaining to Article 311 which<br />

is contained in Part XIV of the Constitution was<br />

inapposite. What was under consideration was Article 12<br />

which by definition is limited to Part III and by virtue of<br />

Article 36 to Part IV of the Constitution, as said by<br />

another Constitution Bench later in this context.”<br />

In the course of the judgment, the Supreme Court of India further<br />

observed as under:-<br />

“Normally, a precedent like Sabhajit Tewary which has<br />

stood for a length of time should not be reversed, however<br />

erroneous the reasoning if it has stood unquestioned,<br />

without its reasoning being “distinguished” out of all<br />

recognition by subsequent decisions and if the principles<br />

enunciated in the earlier decision can stand consistently

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 20<br />

and be reconciled with subsequent decisions of this Court,<br />

some equally authoritative. In our view Sabhajit Tewary<br />

fulfils both conditions.”<br />

14. We have carefully considered the contentions of Mr.<br />

Khaki, as also of the learned counsel for the petitioners and the view<br />

expressed by the learned Attorney General for Pakistan on the<br />

maintainability of the present petition in regard to the power and<br />

jurisdiction of this Court to revisit and overrule its earlier judgment.<br />

We may usefully make reference to the following cases: -<br />

Ataur Rahman v. State (PLD 1967 SC 23): The judgment<br />

points out the possibility of re-considering in a future<br />

proper case Court’s view on a point of law expressed in<br />

earlier case and decision in earlier case remaining<br />

binding on Courts till such re-consideration.<br />

Allah Ditta v. Muhammad Ali (PLD 1972 SC 59): The<br />

Supreme Court of Pakistan held that “----, the decision in<br />

the case of Sharaf and another v. Pir Bakhsh 1 and<br />

another has held the field for the last 78 years and has<br />

been followed without dissent by the Courts in Punjab.<br />

On the principle of ‘stare decisis’ also it is not desirable to<br />

change this view unless it is so unreasonable that it<br />

cannot be followed under any circumstances.”<br />

Terni S.P.A. v. PECO (1992 SC<strong>MR</strong> 2238): It was held that<br />

this Court could depart from a previous rule or<br />

interpretation if it felt that circumstances had changed<br />

and that not to do so would lead to injustice. The<br />

development of the law should not be permitted to be<br />

stifled. It should move with the time and articulate the<br />

changes coming in.<br />

Muhammad Hanif v. Sultan (1994 SC<strong>MR</strong> 279): This Court<br />

observed that the Supreme Court being at the apex had a<br />

constitutional duty to do complete justice, thus, it could<br />

not be inhibited by any restraint and had an abiding duty<br />

to attend to all aspects and to take an overall view of the<br />

case in dispensing justice.<br />

In re: To Revisit “The State v. Zubair” (2002 SC<strong>MR</strong> 171):<br />

This Court took suo motu action in the matter under<br />

Article 184(3) of the Constitution in view of the difficulties<br />

arising out of the strict implementation of the ratio in<br />

1 83 Punjab Record 1893

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 21<br />

Zubair’s case wherein it was, inter alia, observed by this<br />

Court that if a Judge of a High Court had heard a bail<br />

application of an accused person, all subsequent<br />

applications for bail of the same accused or in the same<br />

case, should be referred to the same Bench/Judge<br />

wherever he was sitting and in case it was absolutely<br />

impossible to place the second or subsequent bail<br />

application before the same Judge who had dealt with the<br />

earlier bail application of the same accused or in the<br />

same case, the Chief Justice of the concerned High Court<br />

may direct it to be fixed for disposal before any other<br />

Bench/Judge of that Court. In this case, while making<br />

certain clarifications/modifications in its earlier judgment<br />

in Zubair’s case, this Court was influenced by the<br />

following factors: -<br />

“---- the rule in Zubair (supra) is based on the<br />

salutary principles that justice must not only be<br />

done but also seen to be done. It also promotes the<br />

Constitutional ideals that no one should abuse the<br />

process of the Court (Article 204) and the<br />

independence of the judiciary must be fully secured<br />

(Article 2A). These ideals cannot, however, be fully<br />

promoted unless the rule in Zubair (supra) is made<br />

to accommodate the equally important<br />

Constitutional ideals of expeditious and inexpensive<br />

justice (Article 37(d) I which though a Principle of<br />

Policy can be judicially enforced as it will be read<br />

into the non-derogable Fundamental Rights<br />

guaranteeing the inviolability of the dignity of man<br />

(Article 14). Keeping bail applications pending for<br />

long periods of time by making a fetish of<br />

technicalities not only denies these Constitutional<br />

ideals but also impedes access to justice which is a<br />

Fundamental Right protected by Article 14.”<br />

15. From the above survey of the case-law it is clear that the<br />

Supreme Court in an appropriate case may revisit its earlier<br />

decision, clarify, modify or even overrule the same if the<br />

circumstances of the case so warrant.<br />

16. The learned counsel for the petitioners contended that the<br />

impugned educational qualification constituted infringement of<br />

fundamental right of the citizens, but it was taken very lightly in the<br />

PML (Q)’s case. He submitted that the Court in the said case

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 22<br />

recapitulated the events of the Pakistan’s recent political history in<br />

great detail but paid a little attention to the question of enforcement<br />

of the fundamental rights. He contended that the Court sufficed by<br />

making the following discussion on the issue: -<br />

“Article 17 clearly allows a citizen to have the right to form<br />

associations or unions subject to any reasonable<br />

restrictions imposed by law. Similarly, every citizen not<br />

being in the service of Pakistan, has the right to form or be<br />

a member of political party, subject to any reasonable<br />

restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the<br />

sovereignty or integrity of Pakistan. In this context, we are<br />

reminded of the following observations made by this Court<br />

in Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif’s case at page 558 while<br />

interpreting Article 17 of the Constitution: -<br />

“This approach was again in evidence in the<br />

Symbol’s case (PLD 1989 SC 66) wherein it was<br />

observed that the ‘Fundamental Right’ conferred by<br />

Article 17(2) of the Constitution whereby every<br />

citizen has been given ‘the right’ to form or to be a<br />

member of a political party comprises the right to<br />

participate in and contest and election.”<br />

The learned counsel submitted that having noted the above<br />

interpretation of Article 17, the Court held as under: -<br />

“There is no cavil with the proposition laid down by this<br />

Court that every citizen has a right to contest election but<br />

the principle enunciated therein does not confer an<br />

unbridled right on every citizen to contest an election. The<br />

right to contest an election is subject to the provisions of<br />

the Constitution and the law and only those citizens are<br />

eligible to contest election who possess the qualifications<br />

contained in Article 62 and the law including the law<br />

made under Article 62(i) and do not suffer from<br />

disqualifications laid down in Article 63 of the<br />

Constitution and the law.”<br />

17. The learned counsel for the petitioners submitted that<br />

soon after the decision of PML (Q)’s case, Article 17 again fell for<br />

consideration in Javed Jabbar’s case where the Court returned a<br />

different finding on somewhat similar issues. It may be recalled that<br />

by amending the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002, Article 8-AA

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 23<br />

was added providing therein that a person who had unsuccessfully<br />

contested election to the National or a Provincial Assembly was not<br />

eligible to contest the Senate election. For facility of reference, Article<br />

8-AA of the Chief Executive’s Order No. 7 of 2002 is reproduced<br />

below: -<br />

“8-AA. Disqualification from being a member of the<br />

Senate. – Notwithstanding anything contained in the<br />

Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973, the<br />

Senate (Election) Act, 1975 (LI of 1975), the<br />

Representation of the People Act, 1976 (LXXXV of 1976),<br />

or any other law for the time being in force, a person shall<br />

be disqualified from being elected or chosen as, and from<br />

being, a member of the Senate if, having been a candidate<br />

for Election to the National Assembly or a Provincial<br />

Assembly at the elections held under this Order he has<br />

not been elected to such Assembly.”<br />

The above disqualification for the Senate election was challenged<br />

before this Court in Constitution Petitions No. 38 of 2002 etc. in the<br />

case of Javed Jabbar (supra) and the Court held the disqualification<br />

attributable to defeat in consequence of lawful act of contesting<br />

election of the National or a Provincial Assembly as discriminatory in<br />

nature and violative of Article 25 of the Constitution. At Para 22 of<br />

the judgment, the Court held as under: -<br />

“22. Adverting to the second common contention we find<br />

that Article 8-AA of the Order not only offends the<br />

provisions of Article 25 of the Constitution, which<br />

guarantees that all citizens are equal before law, but is<br />

also unjust as its promulgation after completion of the<br />

process of general elections has left the petitioners high<br />

and dry. Participation in an election is a positive act which<br />

advances the cause of democracy and flows from the<br />

fundamental right of a person to contest an election which<br />

is enshrined in the Constitution and acknowledged in the<br />

Statutes on the subject. It is indeed unfair to sideline a<br />

candidate defeated in the general elections through a<br />

belatedly prescribed disqualification which is<br />

discriminatory in nature, militates against the spirit of<br />

democracy and tends to frustrate the process of Senate<br />

election. The amending Order was promulgated after

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 24<br />

completion of the process of general elections and those<br />

who intended to contest elections to the National<br />

Assembly and the Provincial Assemblies were not aware<br />

that in the event of defeat they would be disqualified to<br />

participate in the Senate election. We are convinced that<br />

had the disqualification in question been incorporated in<br />

the Order at the outset the candidates desirous of<br />

contesting the Senate election would not have contested<br />

election to the National Assembly and the Provincial<br />

Assemblies and thus could have opted for a different<br />

course of action. The timing of the impugned legislation is<br />

crucial in the facts and circumstances of the present case<br />

and is fatal to the case of the Federation. Resultantly, the<br />

impugned legislation, although competently enacted and<br />

immune from challenge on the ground of mala fides,<br />

cannot be allowed to remain on the Statute book being<br />

violative of the provisions of Article 25 of the Constitution<br />

and having been introduced belatedly.”<br />

It may also be advantageous to re fer to Para. 16 of the judgment<br />

which reads as follows: -<br />

“16. In view of the above interpretation of the expression<br />

"public importance", the status and importance of the<br />

Senate which is an integral part of Majlis-e-Shoora<br />

(Parliament) and consists of the chosen representatives of<br />

the people, mode of election of members of the Senate,<br />

prerogative of the political parties to award tickets to<br />

persons of their choice and solicited scrutiny of the<br />

amending Order there is no difficulty in holding that the<br />

petitions involve a question of public importance within<br />

the contemplation of Article 184(3) of the Constitution. As<br />

regards infringement and enforcement of a fundamental<br />

right of the petitioners, suffice it to say that right to<br />

contest an election is not only a statutory but also a<br />

fundamental right conferred by Chapter 1 of Part II of the<br />

Constitution. Every citizen who fulfils the conditions laid<br />

down under Articles 62 and 63 of the Constitution and the<br />

related law is eligible to contest an election and to<br />

participate in the ensuing formation of Government either<br />

in his individual capacity or as a member of a political<br />

party. Such right is guaranteed under Article 17(2) of the<br />

Constitution and has been recognized as such in Mian<br />

Muhammad Nawaz Sharif v. President of Pakistan PLD<br />

1993 SC 473 and Pakistan Muslim League (Q) v. Chief<br />

Executive of Islamic Republic of Pakistan PLD 2002 SC<br />

994. The observations made in the case of Pakistan<br />

Muslim League (Q) read as under: -<br />

"24. It was next urged before us that the Election<br />

Order is ultra vires Articles 17 and 25 of the

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 25<br />

Constitution. We will first reproduce Article 17 of the<br />

Constitution, which reads as under: -<br />

"17. (1) Every citizen shall have the right to<br />

form associations or unions, subject to any<br />

reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the<br />

interest of sovereignty or integrity of Pakistan,<br />

public order or morality.<br />

(2) Every citizen, not being in the service of<br />

Pakistan, shall have the right to form or be a<br />

member of a political party, subject to any<br />

reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the<br />

interest of the sovereignty or integrity of<br />

Pakistan and such law shall provide that where<br />

the Federal Government declares that any<br />

political party has been formed or is operating<br />

in a manner prejudicial to the sovereignty or<br />

integrity of Pakistan, the Federal Government<br />

shall, within fifteen days of such declaration,<br />

refer the matter to the Supreme Court whose<br />

decision on such reference shall be final.<br />

(3) Every political party shall account for the<br />

source of its funds in accordance with law."<br />

Article 17 clearly allows a citizen to have the right to form<br />

associations or unions subject to any reasonable<br />

restrictions imposed by law. Similarly, every citizen not<br />

being in the service of Pakistan, has the right to form or be<br />

a member of a political party, subject to any reasonable<br />

restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the<br />

sovereignty or integrity oil Pakistan. In this context, we are<br />

reminded of the following observations made by this Court<br />

in Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif's case at page 558<br />

while interpreting Article 17 of the Constitution: -<br />

“This approach was again in evidence in the<br />

Symbol’s case PLD, 1989 SC 66 wherein it was<br />

observed that the ‘Fundamental Right’ conferred by<br />

Article 17(2) of the Constitution whereby every<br />

citizen has been given ‘the right’ to form or to be a<br />

member of a political party comprises the right to in<br />

and contest an election.”<br />

There is no cavil with the proposition laid down by this<br />

Court that every citizen has a right to contest election but<br />

the principle enunciated therein does not confer an<br />

unbridled right on every citizen to contest an election. The<br />

right to contest an election is subject to the provisions of<br />

the Constitution and the law and only those citizens are<br />

eligible to contest election who possess the qualifications

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 26<br />

contained in Article 62 and the law including the law<br />

made under Article 62(i) and do not suffer from<br />

disqualifications laid down in Article 63 of the<br />

Constitution and the law.”<br />

18. The learned counsel further submitted that in PML (Q)’s<br />

case, on the question of reasonable classification permissible under<br />

Article 25, the Court noted the principles stated in I.A. Sharwani’s<br />

case and summed up the discussion with the following remarks:-<br />

“We need not refer to the plethora of case-law on the<br />

subject because the above principles summarize the entire<br />

case-law. Judging the Election Order in the light of the<br />

above principles, we are of the view that the education<br />

related qualification is reasonable and not arbitrary or<br />

whimsical because firstly, being a step towards<br />

transformation of the political culture it is founded on<br />

reasonable basis and secondly, it equally applies to all the<br />

graduates and does not discriminate any graduate or<br />

create a class within the graduates.”<br />

Thus, the learned counsel for the petitioners contended that not only<br />

there was divergence in the approach of the Court towards the two<br />

cases involving similar issues, it also did not advert to the<br />

fundamental question requiring determination whether the impugned<br />

educational qualification was reasonable on the touchstone of Articles<br />

17(2) and 25 of the Constitution. He submitted that in PML (Q)’s case<br />

the Court held the graduation qualification as reasonable because of<br />

its equal application to all the graduates and there being no further<br />

classification of the graduates. But, in Javed Jabbar’s case, the Court<br />

held that the impugned legislation, although competently enacted<br />

and immune from challenge on the ground of mala fides, could not be<br />

allowed to remain on the statute book being violative of the provisions<br />

of Article 25 of the Constitution. It could well be said that the<br />

disqualification applied to all those persons who had lost election of

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 27<br />

the National or a Provincial Assembly and no class was created within<br />

them.<br />

19. The learned Attorney General for Pakistan made reference<br />

to the case of Farooq Ahmed Khan Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan<br />

(PLD 1999 SC 57) to contend that all efforts were to be made to<br />

preserve and to enlarge the scope of fundamental rights while<br />

interpreting the constitutional provisions.<br />

20. The question of infringement of fundamental rights has<br />

engaged the attention of the Superior Courts, which have always<br />

dealt with these matters in all earnestness. In the case of F.B. Ali v.<br />

State (PLD 1975 SC 506) this Court elucidated the equal protection<br />

clause as under: -<br />

“Equal protection of the laws does not mean that every<br />

citizen, no matter what his condition, must be treated in<br />

the same manner. The phrase ‘equal protection’ of the<br />

laws means that no person or class of persons shall be<br />

denied the same protection of laws which is enjoyed by<br />

other persons or other class of persons in like<br />

circumstances in respect of their life, liberty, property or<br />

pursuits of happiness. This only means that persons,<br />

similarly situated or in similar circumstances, will be<br />

treated in the same manner. Besides this, all law implies<br />

classification, for, when it applies to a set of<br />

circumstances, it creates thereby a class and equal<br />

protection means that this classification should be<br />

reasonable. To justify the validity of a classification, it<br />

must be shown that it is based on reasonable distinctions<br />

or that it is on reasonable basis and rests on a real or<br />

substantial difference of distinction. Thus different laws<br />

can validly be made for different sexes, for persons in<br />

different age groups, e.g., minors or very old people;<br />

different taxes may be levied from different classes of<br />

persons on the basis of their ability to pay. Similarly,<br />

compensation for properties acquired may be paid at<br />

different rates to different categories of owners. Such<br />

differentiation may also be made on the basis of<br />

occupations or privileges or the special needs of a<br />

particular locality or a particular community. Indeed, the<br />

bulk of the special laws made to meet special situation<br />

come within this category. Thus, in the field of criminal

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 28<br />

justice, a classification may well be made on the basis of<br />

the heinousness of the crime committed or the necessity<br />

or preventing certain anti-social effects of a particular<br />

crime. Changes in procedure may equally well be effected<br />

on the ground of the security of the State, maintenance of<br />

public order, removal of corruption from amongst public<br />

servants or for meeting an emergency.<br />

Where, however, the law itself makes no classification but<br />

leaves the selection to an outside agency or an<br />

administrative body without laying down any guidelines,<br />

thus enabling the body or authority to pick and choose, a<br />

legitimate complaint may be made on the ground that the<br />

law itself permits discriminatory application. Such was the<br />

position which came under consideration by this Court in<br />

the case of Waris Meah v. The State (1) 1 where this Court<br />

struck down the law on the ground that it was violative of<br />

this particular right. On the other hand, in the case of<br />

Jibendra Kishore Achharya v. Province of East Pakistan<br />

(2) 2 , a law which provided for payment of compensation on<br />

a sliding scale to proprietors, which decreased in<br />

proportion to the income of the estate acquired. The larger<br />

the income the lesser the scale of compensation.<br />

Nevertheless, this Court held the differentiation to be<br />

based upon a valid classification.<br />

The concept of the ‘equal protection of law’, which is<br />

derived from the American Constitution is not susceptible<br />

of any exact definition. “In other words”, as stated by the<br />

editors of American Jurisprudence, Vol. 12, page 409, “no<br />

rule as to protection of laws that will cover every case can<br />

be formulated and no test of the type of cases involving<br />

such a clause of the Constitution can be infallible or allinclusive.<br />

Moreover, it would be impracticable and unwise<br />

to attempt to lay down any generalization covering the<br />

subject; each case must be decided as it arises.” Be that<br />

as it may, the only generalization that is possible is that it<br />

means “subjection to equal laws applying to all in the<br />

same circumstances” but this does not mean that laws<br />

must affect every man, woman and child alike. This<br />

guarantee does not forbid discrimination with respect to<br />

things that are different nor does it prohibit classification<br />

which is reasonable and is based upon substantial<br />

differences having a relation to the objects or persons<br />

dealt with and to the public purpose sought to be<br />

achieved. It guarantees equality and not identity of rights.<br />

The principle is well recognized that a State may classify<br />

persons and objects for the purpose of legislation and<br />

1 PLD 1957 SC (Pak) 157<br />

2 PLD 1957 SC (Pak.) 9

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 29<br />

make laws applicable only to persons or objects within a<br />

class. In fact almost all legislation involves some kind of<br />

classification whereby some people acquire rights or suffer<br />

disabilities which others do not. What, however, it<br />

prohibited under this principle is legislation favouring<br />

some within a class and unduly burdening others.<br />

Legislation affecting alike all persons similarly situated is<br />

not prohibited. The mere fact that legislation is made to<br />

apply only to a certain group of persons and not to others<br />

does not invalidate the legislation if it is so made that all<br />

persons subject to its terms are treated alike under similar<br />

circumstances. This is considered to be permissible<br />

classification.”<br />

Reference may also be made to the case of Muhammad Nawaz Sharif<br />

v. Federation of Pakistan (PLD 1993 SC 473), where Chief Justice Dr.<br />

Nasim Hasan Shah held as under: -<br />

Fundamental Rights in essence are restraints on the<br />

arbitrary exercise of power by the State in relation to any<br />

activity that an individual can engage. Although<br />

Constitutional guarantees are often couched in permissive<br />

terminology, in essence they impose limitations on the<br />

power of the State to restrict such activities, Moreover,<br />

Basic or Fundamental Rights of individuals which<br />

presently stand formally incorporated in the modern<br />

Constitutional documents derive their lineage from an are<br />

traceable to the ancient Natural Law. With the passage of<br />

time and the evolution of civil society great changes occur<br />

in the political, social and economic condition of society.<br />

There is, therefore, the corresponding need to re-evaluate<br />

the essence and soul of the Fundamental Rights as<br />

originally provided in the Constitution. They require to be<br />

construed in consonance with the changed conditions of<br />

the society and must be viewed and interpreted with a<br />

vision to the future. Indeed, this progressive approach has<br />

been adopted by the Court in the United States and the<br />

reason given for doing so is that –<br />

‘While the language of the Constitution does not<br />

change, the changing circumstances of a progressive<br />

society for which it was designed yield a new and<br />

fuller import to its meaning: (Hurtade v. California—<br />

110 US 516)’.”<br />

At Para 17 of the above judgment, Ajmal Mian, J., as he then was,<br />

(later Chief Justice) observed as under: -

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 30<br />

“I may also observe that there is a marked distinction<br />

between interpreting a Constitutional provision containing<br />

a Fundamental Right and a provision of an ordinary<br />

statute. A Constitutional provision containing<br />

Fundamental right is a permanent provision intended to<br />

cater for all time to come and, therefore, while interpreting<br />

such a provision the approach of the Court should be<br />

dynamic, progressive and liberal keeping in view ideals of<br />

the people, socio-economic and politico-cultural values<br />

(which in Pakistan are enshrined in the Objectives<br />

Resolution) so as to extend the benefit of the same to the<br />

maximum possible. This is also called judicial activism or<br />

judicial creativity. In other words, the role of the Courts is<br />

to expand the scope of such a provision and not to<br />

extenuate the same.”<br />

21. In the same context, our attention was also invited to<br />

Government of Balochistan v. Azizullah Memon (PLD 1993 SC 341). In<br />

that case, the learned Advocate General had contended that the<br />

special requirement of the area, namely, Balochistan was that it had<br />

a tribal society where usage and custom were deep-rooted and they<br />

required to be dealt with differently from other areas of Pakistan. The<br />

Court did not agree with the reasoning put forward by the learned<br />

Advocate General and held that the said criterion would be available<br />

to the Government for making such laws in pre-independence period<br />

when the British were ruling the area as a colony and had their own<br />

policy to dominate and subjugate the citizens. But after independence<br />

of the country entire scenario had changed. The Court took into<br />

consideration the object of the Criminal Law (Special Provisions)<br />

Ordinance, 1968, which was to provide a system different from the<br />

established procedure for trial of certain offences in certain areas of<br />

West Pakistan specified in the Schedule to meet the special<br />

requirements of those areas. The Court held that the people who had<br />

fought for independence would clamour for a just and proper order

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 31<br />

according to general law of the land, the Constitution and Injunctions<br />

of Islam. The Court repelled the contention of the learned Advocate<br />

General that the Ordinance was made applicable to the entire<br />

Province of Balochistan and there was no race or class<br />

discrimination. As such, the Ordinance was declared to be void being<br />

in conflict with Articles 9, 25, 175 and 203 of the Constitution. The<br />

Court held as under:-<br />

“As the judgments from Indian jurisdiction have been<br />

considered in the afore-stated judgments of this Court, we<br />

would not refer to them here. In all these authorities there<br />

seems to be a unanimity of view that although class<br />

legislation has been forbidden, it permits reasonable<br />

classification for the purpose of legislation. Permissible<br />

classification is allowed provided the classification is<br />

founded on intelligible differentia which distinguishes<br />

person or things that are grouped together from others<br />

who are left out of the group and such classification and<br />

differentia must be on relational relation to the objects<br />

sought to be achieved by the Act. There should be a nexus<br />

between the classification and the objects of the Act. This<br />

principle symbolizes that persons or things similarly<br />

situated cannot be distinguished or discriminated while<br />

making or applying the law. It has to be applied equally to<br />

persons situated similarly and in the same situation. Any<br />

law made or action taken in violation of these principles is<br />

liable to be struck down. If the law clothes any statutory<br />

authority or functionary with unguided and arbitrary<br />

power enabling it to administer in a discriminatory<br />

manner, such law will violate equality clause. Thus, the<br />

substantive and procedural law and action taken under it<br />

can be challenged as violative or Articles 8 and 25.”<br />

22. Having gone through the case-law cited at the bar<br />

including judgments in PML (Q) and Javed Jabbar’s cases, we find<br />

force in the submissions of the learned counsel for the petitioners and<br />

the learned Attorney General for Pakistan. Needless to observe that<br />

the questions of law of public importance with reference to<br />

enforcement of fundamental rights have to be properly dealt with. We

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 32<br />

are satisfied that a case for revisiting the judgment of this Court in<br />

PML (Q)’s case is made out.<br />

23. The learned counsel for the petitioners contended that in<br />

view of the ratio laid down in the cases of Benazir Bhutto and<br />

Muhammad Nawaz Sharif (supra), the right to form or be a member of<br />

a political party enshrined in Article 17(2) of the Constitution<br />

included the right to form government and to contest election.<br />

According to him, Article 17(2) had two parts: one granted the right to<br />

a citizen to form or be a member of a political party, and the other<br />

placed a restriction on the right, in that, such a person was not in the<br />

service of Pakistan. On the contrary, Mr. Khaki drew support from the<br />

judgment in PML (Q)’s case and canvassed the proposition that to<br />

contest election, no doubt, was a fundamental right but this right was<br />

a qualified one. According to him, the fundamental right to participate<br />

in election was also subject to certain restrictions imposed by law as<br />

provided in Article 17 of the Constitution. He further submitted that if<br />

the impugned legislation was struck down, it would call for a fresh<br />

election of the Parliament and the Provincial Assemblies. Therefore, at<br />

least the petition ought to be amended by impleading the President<br />

and Members of the Parliament as parties to it.<br />

24. In the case reported as Muhammad Yousuf v. State (2002<br />

CLC 1130) the Supreme Court of Azad Jammu and Kashmir took the<br />

view that only such persons could enter a legislative body who were<br />

either matriculate or had equivalent qualification and the same would<br />

not be violative of Fundamental Right No.7 of the Azad Jammu &<br />

Kashmir Interim Constitution, 1974 (Act NO. VIII of 1974)

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO. 1 OF 2008<br />

AND CMA NO. 994 TO 996 OF 2008 33<br />

(corresponding of Article 17 of our Constitution). At paragraphs 18,<br />

19 and 21 of the judgment, the Court held as under: -<br />

“18. From the perusal of Fundamental Right No.7 it<br />

would appear that every State Subject has been given<br />