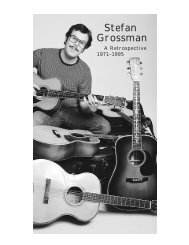

Legends of Jazz Guitar - Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop

Legends of Jazz Guitar - Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop

Legends of Jazz Guitar - Stefan Grossman's Guitar Workshop

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

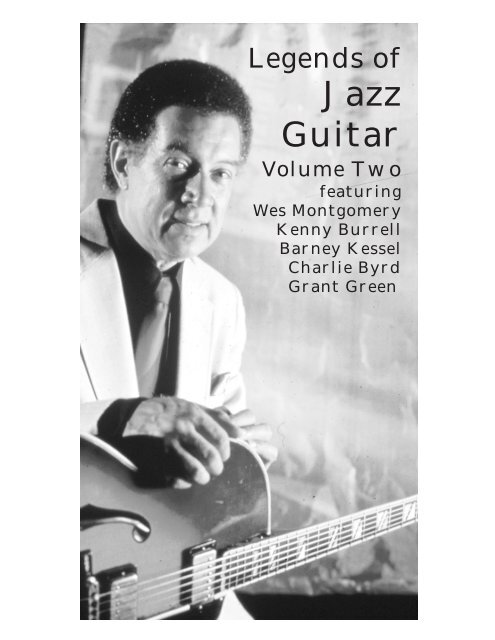

<strong>Legends</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Jazz</strong><br />

<strong>Guitar</strong><br />

Volume Two<br />

featuring<br />

Wes Montgomery<br />

Kenny Burrell<br />

Barney Kessel<br />

Charlie Byrd<br />

Grant Green

LEGENDS OF JAZZ GUITAR<br />

VOLUME TWO<br />

by Mark Humphrey<br />

What becomes a legend most?<br />

Judging from the dazzling<br />

improvisatory exchanges in the<br />

trio performance which opens this<br />

video, perhaps it’s comradely<br />

competition. Then again, it may<br />

be the challenge a master improviser<br />

like Joe Pass makes <strong>of</strong> the blues idiom.<br />

Rhythms that are anything but routine<br />

please these legends, as do the<br />

harmonic textures they extract from<br />

standards. Drive delights these legends,<br />

but so, too, does understatement.<br />

Variety apparently becomes these<br />

legends best. They deliver dynamics,<br />

sundry shades <strong>of</strong> blue and brighter<br />

tonal colors as well. Chameleon-like,<br />

they change sonic shades without<br />

notice. They run the gamut<br />

from playfully funky to<br />

moody and meditative,<br />

and it is their absolute<br />

mastery <strong>of</strong> so much<br />

emotional and musical<br />

territory which justifies<br />

calling these<br />

artists legends.<br />

2

BARNEY KESSEL<br />

“Above all, the humanness <strong>of</strong> a performer should<br />

be apparent...the essence <strong>of</strong> a living being is greater<br />

than the music. The music is only an expression<br />

<strong>of</strong> that essence.” — Barney Kessel<br />

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

Articulate and passionate, Barney Kessel has been<br />

a crusader for jazz since discovering it in his teens in<br />

Muskogee, Oklahoma. That was Kessel’s birthplace in<br />

1923, and it was there he first explored jazz in an otherwise-black<br />

band at age 14. “I knew what I wanted to find,”<br />

Kessel once remarked <strong>of</strong> his first forays into jazz, “and I<br />

used the guitar to find it.”<br />

Finding Charlie Christian grooving to his playing at<br />

an Oklahoma City club was the shock <strong>of</strong> Kessel’s life.<br />

Christian’s encouraging words (“I’m gonna tell Benny<br />

about you”) inspired the sixteen-year-old Kessel to strike<br />

out on his own, first to the upper Midwest and ultimately<br />

to California. There his presence at jam sessions brought<br />

him to the attention <strong>of</strong> producer-promoter Norman Granz,<br />

who enlisted Kessel (along with Lester Young and other<br />

greats) for the 1944 film short, Jammin’ the Blues. Kessel<br />

soon took the guitar chair in a succession <strong>of</strong> notable big<br />

bands, including those <strong>of</strong> Artie Shaw, Charlie Barnet, and<br />

Benny Goodman. He began exploring bebop when Dizzy<br />

3

Photo Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Ashley Mark Publishing Co.<br />

Gillespie and Charlie Parker came to Los Angeles in 1945.<br />

He played with Parker on a 1946 Dial Records session<br />

and became a mainstay <strong>of</strong> the Hollywood studios, backing<br />

everyone from Bird to Billie Holiday.<br />

In 1952, Kessel joined Oscar Peterson’s trio. His tenmonth<br />

stint with the group brought him greater attention<br />

and gave him the confidence to begin recording and performing<br />

as leader. Despite a busy schedule <strong>of</strong> session<br />

work, Kessel became the leading voice <strong>of</strong> jazz guitar in<br />

the 1950s. He routinely walked away with the guitar honors<br />

in down beat’s annual poll until Wes Montgomery<br />

unseated him in 1963.<br />

Kessel continued to be an active and influential force<br />

in jazz guitar throughout the 1960s-1980s. His composition,<br />

“Blue Mist,” is the springboard for stunning ‘conversations’<br />

among Kessel, Kenny Burrell, and Grant<br />

Green captured at Ronnie Scott’s in London in 1969. An<br />

example <strong>of</strong> jazz artistry at its peak, the exchange <strong>of</strong> solos<br />

culminates with each guitarist making statements<br />

brilliantly extended by the others.<br />

1974’s “BBC Blues” is a Kessel revision <strong>of</strong> “Basie’s<br />

Blues” (see <strong>Legends</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Jazz</strong> <strong>Guitar</strong>, Volume One) with a<br />

title honoring the company which taped it. It’s an example<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kessel in top form exhibiting what Norman<br />

Mongan, in The History <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Guitar</strong> in <strong>Jazz</strong>, calls “His<br />

4

personal mannerisms — the upward (or backward) rake<br />

across the strings, the extroverted use <strong>of</strong> blue notes,<br />

smears, chordal solos — (which) make his approach immediately<br />

recognizable.” And Kessel’s signature sound<br />

has become an indelible part <strong>of</strong> jazz guitar history. “You<br />

look at the guitar as a tool,” he told Arnie Berle, “to help<br />

you manifest what it is you already hear — to bring out<br />

what you have inside.”<br />

Photo Courtesy <strong>of</strong> Tropix International<br />

KENNY BURRELL<br />

“I can spot his playing anywhere. His chord<br />

conception is wonderful, and you’re always aware<br />

<strong>of</strong> the harmonic movement in his work.<br />

That’s particularly evident in his single-string<br />

solos. He’s just one <strong>of</strong> the greats.”<br />

— Tal Farlow on Kenny Burrell<br />

“I wanted to<br />

play saxophone,”<br />

Kenny Burrell once<br />

said, “but we could<br />

not afford a sax.”<br />

Born in Detroit in<br />

1931, Burrell grew<br />

up in a musical family<br />

(his older brother<br />

Billy played guitar,<br />

as did his father).<br />

Burrell’s early heroes<br />

were the great<br />

sax men Coleman<br />

Hawkins and Lester<br />

Young, but he discovered<br />

a guitarist<br />

<strong>of</strong> comparable genius<br />

when he heard<br />

Charlie Christian.<br />

“He wanted to get a<br />

certain sound,” said Burrell, “and he felt this so deeply<br />

that he was able to overcome the limits <strong>of</strong> the instrument<br />

to obtain it.” Burrell got a $10 steel-string and be-<br />

5

gan his own struggle with its limits: “If your feeling is<br />

strong enough,” he observes, “you can get your sound.”<br />

Burrell’s sound was first heard in pianist Tommy<br />

Flanagan’s trio in 1947. At age 19, Burrell was hired by<br />

Dizzy Gillespie for a month and recorded for Gillespie’s<br />

Dee Gee label. Despite many <strong>of</strong>fers to tour, Burrell pursued<br />

a Bachelor <strong>of</strong> Music degree in theory and composition<br />

at Wayne State University. He studied classical guitar<br />

in college, then spent six months subbing for an ailing<br />

Herb Ellis in Oscar Peterson’s trio. In 1956, he moved<br />

to New York, where his reading ability helped him establish<br />

himself in the studios. “There weren’t many guitarists<br />

who could play blues as well as read,” Burrell noted.<br />

His first Blue Note album, Introducing Kenny Burrell (LT-<br />

81523), was recorded in July 1956, and led to years <strong>of</strong><br />

New York-based sessions for Blue Note and Prestige along<br />

with studio work accompanying everyone from James<br />

Brown to Lena Horne.<br />

“If you’re lucky,” says Burrell, “you should be able<br />

to make a living at something you enjoy doing.” Burrell,<br />

whose career has included teaching at UCLA as well as<br />

touring and recording, is extremely lucky. We first encounter<br />

him exchanging volleys with Barney Kessel and<br />

Grant Green in the spectacular “Blue Mist.” Next he appears<br />

at 1987’s San Remo <strong>Jazz</strong> Festival in the company<br />

<strong>of</strong> bassist Dave Jackson and drummer Kenny Washington.<br />

“Lover Man” is an exquisite interpretation <strong>of</strong> this standard<br />

which showcases the qualities (“wonderful chord<br />

conception and harmonic movement”) Tal Farlow admires<br />

in Burrell. The Kurt Weill-Ira Gershwin composition,<br />

“My Ship,” sails on an acoustic steel-string and demonstrates<br />

another side <strong>of</strong> this versatile guitar master.<br />

“When someone turns on the radio and hears four bars<br />

and recognizes that it’s your sound,” says Burrell, “that<br />

is the thing that makes the difference, along with being<br />

really musical and consistent.”<br />

6

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

7

GRANT GREEN<br />

“Green consolidated the place <strong>of</strong> the guitar in the<br />

‘soul-jazz’ movement <strong>of</strong> the early 1960s.”<br />

— Norman Mongan, The History <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Guitar</strong> in <strong>Jazz</strong><br />

St. Louis-born<br />

Grant Green (1931-<br />

1975) was introduced<br />

to the guitar by an<br />

uncle he recalled playing<br />

“old Muddy Waters-type<br />

blues.” His<br />

first instrument was a<br />

Harmony with an amplifier,<br />

Green recalled,<br />

that “looked like an<br />

old-timey radio.” After<br />

a stint with a St. Louis<br />

gospel group, he<br />

served an apprenticeship<br />

playing standards<br />

with accordionist Joe<br />

Murphy, who Green remembered<br />

as “a rarity<br />

and novelty. You just<br />

didn’t find any black people playing accordion then.”<br />

Green’s emergence in the 1960s was hailed by some<br />

critics as a renaissance <strong>of</strong> Charlie Christian’s style: “Green<br />

is particularly concerned with the guitar’s horn-like possibilities,”<br />

wrote Robert Levin, “and has reduced certain<br />

elements <strong>of</strong> Charlie Christian’s approach to their basics.”<br />

Without denying an affinity, Green said he was less consciously<br />

influenced by Christian than he was alto sax giant<br />

Charlie Parker. “Listening to Charlie,” he told Gary<br />

N. Bourland, “was like hearing a different man play every<br />

night.” Listening to Charlie brought Green to jazz.<br />

In 1960, Green moved from St. Louis to New York<br />

after tenor saxophonist Lou Donaldson recommended<br />

Green to Blue Note Records. Green’s debut album,<br />

Grant’s First Stand (Blue Note BLP 4086), met with rave<br />

reviews and initiated a decade which found Green busy<br />

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

8

as session man on Blue Note recordings fronted by Lee<br />

Morgan, Stanley Turrentine, and Jimmy Smith, among<br />

others. Green won down beat’s New Star Award in 1962,<br />

and as part <strong>of</strong> the 1969 triumvirate <strong>of</strong> Kessel, Burrell,<br />

and Green, burned through Kessel’s “Blue Mist” with soulful<br />

fervor.<br />

WES MONTGOMERY<br />

“It doesn’t matter how much artistry one has;<br />

it’s how it’s presented that counts.” — Wes Montgomery<br />

Photo by Chuck Stewart<br />

By any measure <strong>of</strong> artistry and the presentation<br />

there<strong>of</strong>, Wes Montgomery was a giant. Born John Leslie<br />

Montgomery on March 6, 1925, in Indianapolis, Indiana,<br />

Wes was a late bloomer. He took up the guitar at 19, first<br />

a tenor and then a six-string electric. His interest was<br />

fired by the recordings <strong>of</strong> Charlie Christian: “I don’t care<br />

what instrument a cat played,” Montgomery said, “if he<br />

9

didn’t understand and feel the things that Charlie Christian<br />

was doing, he was a pretty poor musician.”<br />

Employed as a welder, Montgomery diligently sat with<br />

his guitar and Charlie Christian records for hours. “The<br />

biggest problem,” he said <strong>of</strong> the guitar, “is getting<br />

started... It’s a very hard instrument to accept, because<br />

it takes years to start working with...” Montgomery was<br />

working well enough with it by 1948 to land a job with<br />

Lionel Hampton, a stint which let him polish techniques<br />

achieved partly by accident: a neighbor’s complaint<br />

prompted Montgomery to drop the pick and try “plucking<br />

the strings with the fat part <strong>of</strong> my thumb. This was<br />

much quieter,” he recalled. The unique attack he developed<br />

with his thumb, along with what Montgomery called<br />

“the trick <strong>of</strong> playing the melody line in two different registers<br />

at the same time — the octave thing,” became his<br />

trademarks. <strong>Guitar</strong>ist Les Spann, who marveled at<br />

Montgomery’s “perfect knowledge <strong>of</strong> the instrument,”<br />

noted that Montgomery’s thumb “gives his playing a very<br />

percussive feeling and remarkable tone.”<br />

As seen in this video, Montgomery was as graceful<br />

and assured as he was dynamic. The apparent effortlessness<br />

<strong>of</strong> his playing was actually the result <strong>of</strong> years <strong>of</strong><br />

hard work: “I used to have headaches every time I played<br />

those octaves,” Montgomery told Ralph Gleason, “because<br />

it was a strain, but the minute I’d quit, I’d be all<br />

right. I don’t why, but it was my way, and my way just<br />

backfired on me. But now I don’t have headaches when I<br />

play octaves. I’m showing you how a strain can capture<br />

a cat and almost choke him, but after awhile it starts to<br />

ease up because you get used to it.”<br />

Montgomery spent most <strong>of</strong> the 1950s giging locally<br />

in Indianapolis while keeping his day job at a radio parts<br />

factory to support his large family. His break came in<br />

1959, when Cannonball Adderly recommended him to<br />

Riverside Records. His recordings were hailed as revelations,<br />

and Montgomery quickly gained a star status unprecedented<br />

in the history <strong>of</strong> jazz guitar. The jazz critics<br />

and aficionados who heralded Montgomery in the early<br />

1960s were dismayed when, shortly after the performances<br />

in this video were made, he began playing jazz<br />

10

versions <strong>of</strong> pop tunes (“Going Out <strong>of</strong> My Head” won Montgomery<br />

a 1966 Grammy). It could be argued that<br />

Montgomery’s jazz-pop hybrid brought jazz guitar a wider<br />

listenership, but the consensus on his music was bitterly<br />

divided at the time a heart attack claimed this giant in<br />

1968.<br />

The accusations <strong>of</strong> ‘selling out’ had yet to be hurled<br />

at Montgomery when he delivered the brilliant performances<br />

captured on this video. Accompanied by pianist<br />

Harold Mabern, bassist Arthur Harper and drummer<br />

Jimmy Lovelace, Montgomery made a 1965 appearance<br />

on the BBC’s <strong>Jazz</strong> 625 program. The sheer joy <strong>of</strong> creating<br />

such joyous music is seen in Montgomery’s face while<br />

playing the saucy “Full House,” an original composition.<br />

Contrasting to its “Take Five”-ish <strong>of</strong>f-kilter rhythms is<br />

the bluesy brilliance <strong>of</strong> Thelonious Monk’s “‘Round Midnight.”<br />

Montgomery’s Riverside recording <strong>of</strong> this on an<br />

album by the same name is regarded as one <strong>of</strong> the greatest<br />

interpretations <strong>of</strong> this standard. Here Montgomery<br />

balances power with understatement superbly supported<br />

by his ensemble’s subtle playing (note the brief shift to a<br />

Bolero rhythm towards the end). A genius who understood<br />

the art <strong>of</strong> sharing the spotlight, Montgomery once<br />

told fellow guitarist Jimmy Stewart: “In jazz music in recent<br />

years, most sidemen want to be the leader and most<br />

leaders want to be the whole show. Very few people reach<br />

the top in their field, and you should not be frustrated by<br />

not reaching the top. The process <strong>of</strong> achieving your goal<br />

is more rewarding than the goal itself.”<br />

11

12<br />

Photo by Tom Copi

CHARLIE BYRD<br />

“Some guitarists impress me.<br />

Some guitarists reach me. Charlie Byrd does both.”<br />

— Herb Ellis on Charlie Byrd<br />

Charlie Byrd’s background is nothing if not eclectic.<br />

Born in Chuckatuck, Virginia, in 1925, Byrd’s first musical<br />

experiences were playing country music on the radio<br />

in Newport News with his father. He later tried his hand<br />

at playing jazz with a pick, only to be seduced by the<br />

sounds <strong>of</strong> the classical guitar. He studied with Segovia in<br />

1954, but experienced a withering revelation: “I really<br />

wasn’t going to be a significant classical guitar player,”<br />

Byrd recalls. Subsequently he decided to arrange some<br />

jazz for classical guitar, and this new sound debuted on a<br />

1956 Savoy label album, <strong>Jazz</strong> Recital.<br />

Byrd’s new approach to jazz found a welcome audience.<br />

He won down beat’s New Star award in 1960, the<br />

same year he toured with Woody Herman’s band. The<br />

following year the State Department sponsored Byrd’s<br />

musical goodwill tour <strong>of</strong> Latin America, an event which<br />

led to Byrd’s role in introducing Brazil’s ‘new beat’ (bossa<br />

nova) sound to America. His duet album with Stan Getz,<br />

13

<strong>Jazz</strong> Samba (Verve<br />

6-8432), was the<br />

breakthrough for<br />

Brazilian music in<br />

America. “I guess<br />

that got me typecast<br />

a little more<br />

than I would have<br />

liked,” Byrd said <strong>of</strong><br />

the bossa nova<br />

craze, “but I like<br />

making arrangements<br />

<strong>of</strong> pretty<br />

tunes and having a<br />

go at improvising<br />

on them.”<br />

He does that<br />

superbly with Fats<br />

Waller’s “Jitterbug<br />

Waltz” in a trio with<br />

his brother, Joe<br />

Byrd, on bass and Wayne Phillips on drums in a 1979<br />

performance for Iowa Public Television (<strong>Jazz</strong> at the Maintenance<br />

Shop). Byrd also takes an eloquent solo turn on<br />

Irving Berlin’s “Isn’t It a Lovely Day,” demonstrating that<br />

classical music’s loss has proven to be jazz’s gain. “I realized,”<br />

Byrd said after his studies with Segovia, “that it<br />

might be a better idea for me to use all my life’s experience,<br />

in jazz and popular music as well, combining them<br />

with classical... There are so many different ways to view<br />

music, and all <strong>of</strong> them can be fruitful. I think the fun is to<br />

pursue your own.”<br />

Photo by Tom Copi<br />

14

Photo by Michael P. Smith<br />

JOE PASS<br />

“...the guitar player has a beautiful tone,<br />

he phrases good, and...it’s really together.”<br />

— Wes Montgomery responding to a ‘blindfold test’<br />

playing <strong>of</strong> Joe Pass’s “Sometime Ago”<br />

Gene Autry was his initial<br />

inspiration to play<br />

guitar. Later, he would<br />

discover the recordings<br />

<strong>of</strong> a fellow Italian-American,<br />

Eddie Lang (born<br />

Salvatore Massaro),<br />

whose version <strong>of</strong> “My<br />

Blue Heaven” especially<br />

impressed him: “He<br />

played a whole chorus in<br />

chords and single notes,”<br />

Joe Pass recalled, “and it<br />

was as modern as<br />

anybody’s playing now.”<br />

It was Pass who brought<br />

the art <strong>of</strong> solo jazz guitar<br />

(“chords and single<br />

notes”) to heights Lang<br />

could scarcely imagine,<br />

as witnessed by his two performances in this video. “What<br />

you have to do,” he reflected, “is develop your own character<br />

in music, your own way <strong>of</strong> doing things.”<br />

Joseph Anthony Passalaqua got a $17 Harmony guitar<br />

for his ninth birthday in 1938. “It had a big, thick<br />

neck,” he recalled, “and was really hard to play.” But<br />

play it he did, sometimes up to six hours a day under the<br />

watchful eye <strong>of</strong> a father who wanted something better<br />

for his son than a steelworker’s life in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.<br />

Pass was playing VFW dances with a local band<br />

at age 12, and before his teens ended he had chalked up<br />

road tours with the big bands <strong>of</strong> Tony Pastor and Charlie<br />

Barnet. By the late 1940s Pass was in New York, jamming<br />

with some <strong>of</strong> the pioneers <strong>of</strong> bebop: “The harmonic<br />

concept, the long melodic lines <strong>of</strong> the solos impressed<br />

15

me,” he recalled, “and I listened to the saxes and trumpets,<br />

trying to play like them.”<br />

Unfortunately, he joined the many jazz artists <strong>of</strong> the<br />

era who fell prey to heroin addiction. From 1949 to 1960,<br />

“I played all over the States in those identical cocktail<br />

lounges with the red leather seating,” Pass recalled, “usually<br />

for a week or two at most... All that time I wasted, I<br />

was a bum, doing nothin’. I could have made it much<br />

sooner but for drugs.” Pass straightened out in 1961, and<br />

his career took <strong>of</strong>f.<br />

His first album as leader, Catch Me (Pacific <strong>Jazz</strong> PJ<br />

73), debuted to raves in 1963. Two years later, Pass joined<br />

the George Shearing Quintet. Pass teamed with pianist<br />

Oscar Peterson in 1969, and his 1973 duet album with<br />

Herb Ellis, <strong>Jazz</strong> Concord (Concord <strong>Jazz</strong> CJ-1), brought<br />

him a still-higher pr<strong>of</strong>ile. Pass unveiled his extraordinary<br />

solo style on 1974’s Virtuoso (Pablo 2310 707), the album<br />

which effectively made a guitar hero <strong>of</strong> Joe Pass.<br />

Watching him play “Original Blues in A” from a mid-<br />

1970s BBC broadcast, it’s easy to see why. Pass drops a<br />

blues cliché long enough to remind us where we are, then<br />

plays dazzling circles around it. The Ellingtonian chestnut,<br />

“Prelude to a Kiss,” provides Pass a springboard for<br />

breathtaking cascades <strong>of</strong> notes and richly textured harmonic<br />

inventions. While he could play punchy and fast<br />

with a pick, Pass preferred to use his fingers for solos<br />

such as these. “Playing with your fingers is much better<br />

for solo guitar,” he declared. “You can get counterpoint,<br />

add bass lines.” In an interview with Tim Schneckloth<br />

(down beat, March 1984), Pass elaborated on this approach:<br />

“The bass lines, for instance, aren’t always happening.<br />

They’re implied sometimes... But by having<br />

motion — keeping the whole thing moving with substitute<br />

chords, a strong pulse, and so on — it sounds like<br />

it’s all happening at the same time.”<br />

16

17<br />

Photo by Tom Copi

1. KESSEL/BURRELL/GREEN<br />

Blue Mist<br />

2. WES MONTGOMERY<br />

Full House<br />

3. JOE PASS<br />

Blues<br />

4. KENNY BURRELL<br />

Lover Man<br />

5. BARNEY KESSEL<br />

BBC Blues<br />

6. CHARLIE BYRD<br />

Jitterbug Waltz<br />

7. WES MONTGOMERY<br />

'Round Midnight<br />

8. JOE PASS<br />

Prelude To A Kiss<br />

9. KENNY BURRELL<br />

My Ship<br />

10. CHARLIE BYRD<br />

Isn't It A Lovely Day<br />

Running Time: 60 minutes • B/W and Color<br />

Front Cover Photo: Kenny Burrell courtesy <strong>of</strong> Tropix Int.<br />

Back Photos: Wes Montgomery by Chuck Stewart<br />

Barney Kessel by Tom Copi<br />

Nationally distributed by Rounder Records,<br />

One Camp Street, Cambridge, MA 02140<br />

Representation to Music Stores by<br />

Mel Bay Publications<br />

® 2001 Vestapol Productions<br />

A division <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Stefan</strong> <strong>Grossman's</strong> <strong>Guitar</strong> <strong>Workshop</strong> Inc.<br />

Virtuosity tempered by taste<br />

and informed by imagination<br />

– it's a constant force in this<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> brilliant jazz<br />

guitar performances. “This is<br />

the magic <strong>of</strong> our kind <strong>of</strong><br />

music,” Barney Kessel has<br />

said <strong>of</strong> jazz improvisation,<br />

and that magic abounds in<br />

these performances. “The<br />

thing is to make music,”<br />

Kenny Burrell once observed,<br />

“no matter what the tempo.<br />

That, to me, is the most<br />

demanding part <strong>of</strong> anything.<br />

It's not the physical or the<br />

technical part. It's just the<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> making it musical.”<br />

The high-wire act <strong>of</strong> balancing<br />

virtuosity and musicality<br />

meets its match in the<br />

remarkable artists seen in this<br />

second volume <strong>of</strong> <strong>Legends</strong><br />

Of <strong>Jazz</strong> <strong>Guitar</strong>.<br />

Vestapol 13033<br />

ISBN: 1-57940-915-6<br />

0 11671 30339 0