Soils, Natural Vegetation, and Wildlife - Department of Geography ...

Soils, Natural Vegetation, and Wildlife - Department of Geography ...

Soils, Natural Vegetation, and Wildlife - Department of Geography ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

3<br />

<strong>Soils</strong>, <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Vegetation</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Combinations <strong>of</strong> physical processes, which are <strong>of</strong>ten modified<br />

through culture, create our ‘natural’ environment. Our environment<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> differing characteristics from the Tidewater<br />

to the Mountain Region. Daily, as well as seasonal, variations in<br />

weather help create an interesting, diverse, <strong>and</strong> ever changing<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape. This chapter presents the soil, natural habitat <strong>and</strong><br />

vegetation, <strong>and</strong> wildlife distributions occurring throughout the<br />

state. These component parts <strong>of</strong> the physical environment play<br />

an important role in underst<strong>and</strong>ing a geographic perspective <strong>of</strong><br />

our state.<br />

SOILS<br />

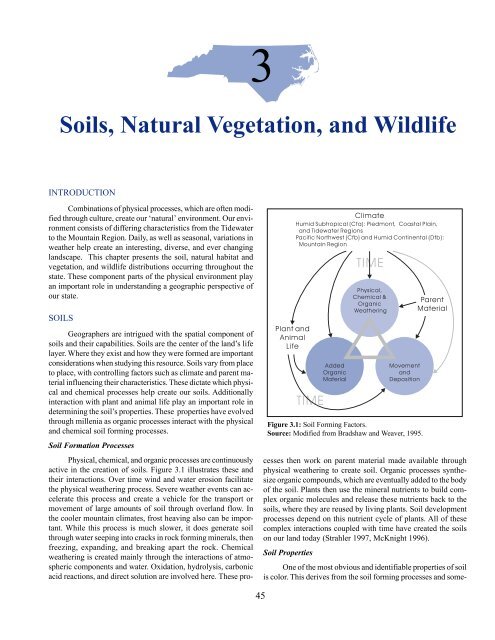

Figure 3.1: Soil Forming Factors.<br />

Source: Modified from Bradshaw <strong>and</strong> Weaver, 1995.<br />

Geographers are intrigued with the spatial component <strong>of</strong><br />

soils <strong>and</strong> their capabilities. <strong>Soils</strong> are the center <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>’s life<br />

layer. Where they exist <strong>and</strong> how they were formed are important<br />

considerations when studying this resource. <strong>Soils</strong> vary from place<br />

to place, with controlling factors such as climate <strong>and</strong> parent material<br />

influencing their characteristics. These dictate which physical<br />

<strong>and</strong> chemical processes help create our soils. Additionally<br />

interaction with plant <strong>and</strong> animal life play an important role in<br />

determining the soil’s properties. These properties have evolved<br />

through millenia as organic processes interact with the physical<br />

<strong>and</strong> chemical soil forming processes.<br />

Soil Formation Processes<br />

Physical, chemical, <strong>and</strong> organic processes are continuously<br />

active in the creation <strong>of</strong> soils. Figure 3.1 illustrates these <strong>and</strong><br />

their interactions. Over time wind <strong>and</strong> water erosion facilitate<br />

the physical weathering process. Severe weather events can accelerate<br />

this process <strong>and</strong> create a vehicle for the transport or<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> large amounts <strong>of</strong> soil through overl<strong>and</strong> flow. In<br />

the cooler mountain climates, frost heaving also can be important.<br />

While this process is much slower, it does generate soil<br />

through water seeping into cracks in rock forming minerals, then<br />

freezing, exp<strong>and</strong>ing, <strong>and</strong> breaking apart the rock. Chemical<br />

weathering is created mainly through the interactions <strong>of</strong> atmospheric<br />

components <strong>and</strong> water. Oxidation, hydrolysis, carbonic<br />

acid reactions, <strong>and</strong> direct solution are involved here. These processes<br />

then work on parent material made available through<br />

physical weathering to create soil. Organic processes synthesize<br />

organic compounds, which are eventually added to the body<br />

<strong>of</strong> the soil. Plants then use the mineral nutrients to build complex<br />

organic molecules <strong>and</strong> release these nutrients back to the<br />

soils, where they are reused by living plants. Soil development<br />

processes depend on this nutrient cycle <strong>of</strong> plants. All <strong>of</strong> these<br />

complex interactions coupled with time have created the soils<br />

on our l<strong>and</strong> today (Strahler 1997, McKnight 1996).<br />

Soil Properties<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most obvious <strong>and</strong> identifiable properties <strong>of</strong> soil<br />

is color. This derives from the soil forming processes <strong>and</strong> some-<br />

45

times is inherited from the parent material. <strong>Soils</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Tidewater<br />

<strong>and</strong> Coastal Plain are a mix <strong>of</strong> color, from the tans <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong>s to<br />

a rich, dark color provided by high organic content, or humus,<br />

in some cases containing a black layer <strong>of</strong> peat (Photo 3.1). Piedmont<br />

soil colors vary, but one is dominant: red clay (CP 3.1). A<br />

form <strong>of</strong> iron, hematite, provides the red hue that has stained<br />

many children’s clothes through the years. The oxidation process<br />

<strong>of</strong> iron or aluminum in parent rock material generates this<br />

color. The Mountains provide a wide mixture <strong>of</strong> colors as physical<br />

weathering processes are vigorously at work. Valley floors<br />

contain the deepest soils <strong>and</strong> most have a dark brown color. The<br />

shallower soils that occupy the slopes <strong>and</strong> the ridges are similar<br />

in color, but without the same pr<strong>of</strong>ile.<br />

<strong>Soils</strong> also are classified or described by their particle size<br />

or texture. Texture classes are based on the proportions <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong>,<br />

silt, <strong>and</strong> clay (expressed as percentages). Figure 3.2 is a Ternary<br />

diagram representation <strong>of</strong> the three components <strong>of</strong> soil used by<br />

the U.S. <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Agriculture, allowing all soil to be classified.<br />

Texture is an important soil property as it determines water<br />

retention <strong>and</strong> transmission rates. For instance, s<strong>and</strong>y soils allow<br />

water to pass through rapidly, while clay soils have very small<br />

particles that do not allow water to pass through easily. Texture,<br />

as well as the organic content <strong>of</strong> the soil, can then be said to<br />

control soil moisture storage capacity, which is its ability to hold<br />

water against the pull <strong>of</strong> gravity. This in turn determines what<br />

plant life a soil might sustain or what might be an appropriate<br />

use <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Mineral properties also are important characteristics <strong>of</strong> the<br />

soil’s personality. <strong>Soils</strong> in the state tend to be acidic due to the<br />

prevalence <strong>of</strong> granitic or gneissic parent material, the warm moist<br />

climate <strong>of</strong> the region, <strong>and</strong> the predominance <strong>of</strong> needle leaf forest<br />

vegetation. Most soils need heavy liming for agricultural productivity<br />

or for having a lush green lawn. In addition, soils may<br />

Figure 3.2: Soil Texture Classes.<br />

suffer from leaching <strong>of</strong> mineral nutrients, particularly nitrogen,<br />

phosphorus, potassium, calcium <strong>and</strong> magnesium, as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

excessive rainfall <strong>and</strong> warm temperatures. Preparation for agriculture<br />

through the application <strong>of</strong> fertilizers is necessary throughout<br />

the state.<br />

While most <strong>of</strong> us normally see only its top layer, a soil<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile is a valuable tool in underst<strong>and</strong>ing the total soil structure,<br />

including its depth. A pr<strong>of</strong>ile, that allows for the inspection<br />

<strong>of</strong> what lies beneath the surface, can be viewed readily by visit-<br />

Photo 3.1: An area <strong>of</strong> the Pamlico Peninsula<br />

in Tyrrell County has been<br />

cleared <strong>and</strong> drainage ditches excavated.<br />

<strong>Soils</strong> are dark <strong>and</strong> rich in humus<br />

<strong>and</strong> sometimes contain a layer<br />

<strong>of</strong> peat, which can also be used as a<br />

fuel source.<br />

46

ing new road cuts or construction sites. Each layer is a soil horizon,<br />

which is a distinctive layer <strong>of</strong> soil set apart from other layers<br />

by differences in physical or chemical composition, organic<br />

content, structure, or a combination <strong>of</strong> those properties. We see<br />

the color transitions from one horizon to the next. Figure 3.3<br />

illustrates a generalized soil pr<strong>of</strong>ile. Figure 3.4 describes a soil<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile from the Mountain region. Often these soils <strong>of</strong> complex<br />

terrain have thin horizons (5 cm/2 in) <strong>and</strong> overall soil depth is<br />

minimal. Topography <strong>and</strong> local relief additionally impact the<br />

soil development process, as shown in Figure 3.5.<br />

Spatial Extent <strong>and</strong> Distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Soils</strong><br />

CP 3.2 shows the spatial extent <strong>and</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> the<br />

state’s soils. As with other physical features <strong>of</strong> the state, the east<br />

to west variation from the Tidewater to the Mountain regions<br />

continues.<br />

The Tidewater coastline consists <strong>of</strong> wide cusps or arcs in<br />

the southern half <strong>and</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s in the northern<br />

half. L<strong>and</strong>scape features like these are a result <strong>of</strong> sediments being<br />

moved by <strong>of</strong>fshore currents as the coast slowly emerges (Box<br />

1B). Poorly drained areas, s<strong>and</strong> flats, bays, <strong>and</strong> sounds dominate<br />

the surface l<strong>and</strong> features. <strong>Soils</strong> <strong>of</strong> this region are relatively<br />

young, generally deep, over 91 cm (36 in), <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> medium to<br />

fine texture. Differences in age <strong>and</strong> thickness are a result <strong>of</strong> various<br />

periods <strong>of</strong> erosion <strong>and</strong> deposition. Wet lowl<strong>and</strong>s or upl<strong>and</strong><br />

bogs (pocosins) are poorly drained with dark colored soils from<br />

decomposed vegetation. These soils belong to the soil order<br />

Histosol meaning “tissue soil”, from decayed plant remains.<br />

Figure 3.3: Soil Pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>and</strong> Horizons.<br />

Source: Modified from Bradshaw <strong>and</strong> Weaver, 1995.<br />

Figure 3.4: Designations <strong>of</strong> Horizons.<br />

Source: Modified from Bradshaw <strong>and</strong> Weaver, 1995.<br />

In the Coastal Plain Region, elevation gradually increases<br />

inl<strong>and</strong> to 91 meters (300 ft) above sea level. Here l<strong>and</strong> surface is<br />

characterized as gently rolling with prominent s<strong>and</strong> hills on the<br />

southwest margin. Most soils <strong>of</strong> the Coastal Plain are deep <strong>and</strong><br />

coarse or s<strong>and</strong>y in texture with heavier s<strong>and</strong>y clay subsoil, hence<br />

the “S<strong>and</strong>hills.” These <strong>and</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the Piedmont soils belong to<br />

the order Ultisols, which are very acidic, highly leached, <strong>and</strong><br />

weathered.<br />

Westward, the Piedmont consists <strong>of</strong> irregular rolling plains<br />

with local relief <strong>of</strong> 30 to 91 meters (100 to 300 ft). Elevations<br />

reach to 457 meters (1,500 ft) east <strong>of</strong> the Brevard Fault. As discussed<br />

earlier, the region is interrupted by erosional remnants<br />

<strong>and</strong> includes the Uwharrie, Sauratown, Kings, Brushy, <strong>and</strong> South<br />

mountains. Piedmont soils are generally over 91 cm (36 in) deep<br />

<strong>and</strong> have heavy, red or yellow clay sub-soils. They are relatively<br />

young due to recent erosion. Differences <strong>of</strong> soil depend mainly<br />

on the type <strong>of</strong> parent material. The Central Piedmont has considerable<br />

alfisol areas, a slightly acid soil derived from more<br />

basic rock.<br />

Topographic complexity <strong>of</strong> the Mountain Region creates<br />

many ‘micro’ environments in which plant <strong>and</strong> animal species<br />

can thrive. This region rises abruptly from the Piedmont along<br />

the Brevard Fault escarpment. The Blue Ridge Mountains comprise<br />

the eastern part <strong>of</strong> this region. Mountain soils tend to be<br />

young due to recent erosion <strong>and</strong> mass wasting on steep slopes<br />

caused by precipitation events. They tend to be shallower here<br />

than in the Piedmont as a result <strong>of</strong> cooler temperatures that re-<br />

47

duce the rate <strong>of</strong> parent material weathering. Sub-soils tend to<br />

have less heavy clay than the Piedmont soils. In broad valleys<br />

<strong>and</strong> basins, soils are more fertile <strong>and</strong> less leached; where a broadleaf<br />

forest dominates, humus is less acidic than in needle leaf<br />

forest. Steep ridges <strong>and</strong> higher mountain areas, especially on<br />

south facing slopes, have thin, acidic soils <strong>of</strong> the Inceptisol order.<br />

Figure 3.5 illustrates typical mountain soil characteristics<br />

<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>form types.<br />

Agricultural <strong>Soils</strong><br />

While the state’s future may lie in high tech industries, its<br />

tradition is agriculture. The majority <strong>of</strong> agricultural l<strong>and</strong>s are<br />

located within the Coastal Plain (CP 1.14). What makes the<br />

Coastal Plain well suited for agriculture? Certainly there is a<br />

complex interaction <strong>of</strong> many factors. The gentle slopes <strong>and</strong> the<br />

soil <strong>and</strong> its capacity to support plant life are dominant factors. A<br />

mixture <strong>of</strong> the right proportions <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong>, silt, <strong>and</strong> clay coupled<br />

with the organic content <strong>of</strong> the soil, provides the foundation for<br />

prime agricultural l<strong>and</strong>s. This type <strong>of</strong> agricultural soil is generally<br />

referred to as loam (Figure 3.2), whose distribution dictate<br />

the most suitable agricultural areas <strong>of</strong> the state (CP 3.2); refer to<br />

CP 1.14 <strong>and</strong> note the coincidence <strong>of</strong> loamy soils to the areas<br />

currently in agricultural use. Additionally, climate (Figure 2.14),<br />

growing season (Figure 2.20), <strong>and</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> ground water<br />

(Figure 1.15) add to the formula <strong>of</strong> agricultural success. Photos<br />

3.2, 3.3, 3.4, <strong>and</strong> 3.5 give testament to the wide variety <strong>of</strong> agricultural<br />

activity in North Carolina, much <strong>of</strong> which is due to soil<br />

resources.<br />

As mentioned earlier, the use <strong>of</strong> soil for agriculture <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

requires input <strong>of</strong> fertilizer, particularly phosphorus <strong>and</strong> potassium.<br />

Application practices vary throughout the state <strong>and</strong> care<br />

should be taken to protect the surface <strong>and</strong> ground water supplies<br />

from the overuse <strong>of</strong> fertilizers; pollution readily occurs through<br />

run<strong>of</strong>f <strong>and</strong> infiltration processes.<br />

Figure 3.5: Mountain <strong>Soils</strong> <strong>and</strong> Topographic Influences.<br />

Source: Modified from Bradshaw <strong>and</strong> Weaver, 1995.<br />

Photo 3.2: Farml<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Triassic<br />

Basin, a transitional<br />

zone between the Coastal<br />

Plain <strong>and</strong> Piedmont regions,<br />

in Harnett County. The l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

takes on a patch like<br />

or quilted character, as fields<br />

<strong>of</strong> different crop types are intermixed<br />

with forested areas.<br />

Sedimentary rock providing<br />

the base for the soils <strong>of</strong> the<br />

region, <strong>and</strong> a long growing<br />

season, have given the area<br />

a longst<strong>and</strong>ing tradition <strong>of</strong><br />

agriculture. (photo by Robert<br />

E. Reiman)<br />

48

Photo 3.3: Strawberry fields are found nestled in<br />

the broad valleys <strong>of</strong> the Inner Piedmont Geologic<br />

Belt where soils are generally deeper <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ten more fertile. This field is located in the<br />

South Mountains (Clevel<strong>and</strong> County) <strong>of</strong> the<br />

western Piedmont Region. Note the peach orchard<br />

on the back edge <strong>of</strong> the field.<br />

Photo 3.4: Apple orchards are common place in<br />

the Brushy Mountains <strong>of</strong> Wilkes <strong>and</strong> Alex<strong>and</strong>er<br />

Counties. Mountain soils <strong>and</strong> climate factors<br />

make the region a productive area for apple<br />

growth. This area recognizes the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

the crop by hosting the Apple Festival each fall.<br />

Photo 3.5: <strong>Soils</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Mountain Region vary<br />

within the complex terrain. Here an area near<br />

the Old Buffalo Trail (Watauga County) is<br />

being prepared for planting. Note the predominance<br />

<strong>of</strong> forest cover still surrounding<br />

this farm <strong>and</strong> the small size <strong>of</strong> the fields<br />

when compared to those <strong>of</strong> the Coastal Plain<br />

<strong>and</strong> Piedmont regions.<br />

49

NATURAL HABITATS AND VEGETATION<br />

As seen in Chapter One, forests provide the most widespread<br />

environmental feature <strong>of</strong> the state. However, North Carolina<br />

supports a great diversity <strong>of</strong> natural vegetation. This is due<br />

in part to the variety <strong>of</strong> climatic <strong>and</strong> topographic conditions or<br />

“habitats”, ranging from the moist, shaded coves <strong>of</strong> the Smokies<br />

to the exposed s<strong>and</strong> dunes <strong>of</strong> the barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s. Figure 3.6 displays<br />

the major vegetation types that are possible in the absence<br />

<strong>of</strong> human impact. Inevitably, people have played an important<br />

role in modifying or introducing vegetation (Box 3A), most noticeably<br />

in managing the pine forests <strong>of</strong> the Piedmont, Coastal<br />

Plain, <strong>and</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the Tidewater region. Pines are generally<br />

intolerant <strong>of</strong> shade <strong>and</strong> would be replaced by broadleaf trees as<br />

the climax vegetation in a natural succession. However, foresters<br />

have maintained pine for its commercial value by controlling<br />

broadleaf species <strong>and</strong> by planting or encouraging natural<br />

seeding <strong>of</strong> desired pine species. In the following discussion <strong>of</strong><br />

vegetation by regions, only the common plant names are used<br />

<strong>and</strong> readers who are interested should refer to Appendix B for<br />

their scientific name equivalents.<br />

Tidewater Habitats<br />

Along the easternmost edge <strong>of</strong> North Carolina are the barrier<br />

isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> outer banks, a thin chain <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong>y beaches <strong>and</strong><br />

marshes. The barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s are situated between the pounding<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Atlantic Ocean to the east <strong>and</strong> the sounds <strong>of</strong> Currituck,<br />

Albemarle, Pamlico, Core, <strong>and</strong> Bogue (Photo 3.6) to the west.<br />

These are popular vacation destinations for millions <strong>of</strong> people<br />

who enjoy the sea air, gentle waves, <strong>and</strong> warm weather. Colder<br />

ocean currents from the north meet the warmer southern currents<br />

at Cape Hatteras <strong>and</strong> have made ocean travel treacherous<br />

in this area for centuries (Early 1993).<br />

Forming a series <strong>of</strong> graceful arcs, these barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s protect<br />

the mainl<strong>and</strong> from the destructive effects <strong>of</strong> powerful storms<br />

<strong>and</strong> their resulting waves (CP 3.3). Several theories regarding<br />

the formation <strong>of</strong> these isl<strong>and</strong>s are presented in Box 1B.<br />

Important wildlife habitats are found on the barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> in nearby waters. Behind the dunes lie the maritime forests<br />

while on the western sides <strong>of</strong> the isl<strong>and</strong>s, fringing the sounds,<br />

salt marshes nurture countless numbers <strong>of</strong> fish, shellfish <strong>and</strong><br />

wildlife. Out on the shallow continental shelf not far from the<br />

isl<strong>and</strong>s, are underwater habitats known as “hardbottoms”, diverse<br />

communities <strong>of</strong> plants <strong>and</strong> animals. Rocky ledges provide<br />

shelter for fish <strong>and</strong> invertebrates whose only other homes are in<br />

the tropical coral reefs or on ship wrecks (Early 1993).<br />

Tidewater <strong>Vegetation</strong><br />

Strong winds, salt spray, shifting s<strong>and</strong>s, extreme heat, desiccation,<br />

<strong>and</strong> flooding create an inhospitable environment for<br />

vegetation adjacent to the coast (Photo 3.7). Only the hardiest<br />

plants can survive. Sea oats <strong>and</strong> American beach grass have been<br />

used extensively in an attempt to stabilize s<strong>and</strong> dunes. Increasing<br />

pressures from development have further complicated this<br />

environmentally sensitive area, <strong>and</strong> attempts to protect ocean<br />

front property have become a priority (Chapter 10). Other plants<br />

found on dunes include croton <strong>and</strong> dune elder. Broomsedge,<br />

spurge, <strong>and</strong> primrose are found in protected areas behind dunes;<br />

Figure 3.6: <strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Vegetation</strong>.<br />

50

all are plants less tolerant <strong>of</strong> salt spray. A maritime thicket <strong>of</strong><br />

yaupon, red cedar <strong>and</strong> wax myrtle <strong>of</strong>ten develops as an asymmetric<br />

mass to the lee <strong>of</strong> ocean winds along the inner dunes.<br />

Behind this thicket is a maritime forest dominated by live oak<br />

<strong>and</strong>, in the northern part, by beech <strong>and</strong> other broadleaf trees,<br />

holdovers from earlier periods when sea level was lower (CP<br />

3.4). Development has caused the loss <strong>of</strong> the majority <strong>of</strong> North<br />

Carolina’s maritime forests. Occasionally, an active dune will<br />

migrate <strong>and</strong> completely cover part <strong>of</strong> this forest. Where the dune<br />

moves on it leaves a stark reminder <strong>of</strong> previous life. Gnarled<br />

<strong>and</strong> wind swept branches are reminiscent <strong>of</strong> high mountain or<br />

arctic growth conditions (Photo 10.1).<br />

Along the sounds (protected by barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s) <strong>and</strong> in<br />

coastal bays are found vast areas <strong>of</strong> salt marsh characterized by<br />

cordgrass <strong>and</strong> needlerush. Freshwater marshes that are flushed<br />

by large coastal rivers, such as the Cape Fear, support bulrush,<br />

cattail, <strong>and</strong> sawgrass.<br />

Coastal Plain Habitat<br />

This low, flat region extends from the fall line toward the<br />

Atlantic Ocean; near the fall line elevations reach 152 meters<br />

(500 feet) above sea level. With so little slope <strong>and</strong> with little<br />

hard rock to flow through, the rivers entering the Coastal Plain<br />

form the rocky Piedmont me<strong>and</strong>er in broad, graceful loops<br />

through the s<strong>of</strong>t layers <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong> (Early 1993).<br />

The s<strong>and</strong>y soils make it clear that the Coastal Plain was<br />

once wholly under water. Over the last two million years, the<br />

sea has inundated it many times, leaving a series <strong>of</strong> terraces across<br />

Photo 3.6: Bogue Sound in Carteret County,<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the smaller sounds, is protected<br />

by the barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s. Saltwater marshes<br />

thrive in the center <strong>of</strong> the narrow sound.<br />

Photo 3.7: As sediments reach the sounds they<br />

no longer can be carried by the rivers that<br />

brought them there <strong>and</strong> are deposited at the<br />

mouths <strong>of</strong> these rivers. Deposition creates<br />

a braided net <strong>of</strong> shallow waters <strong>and</strong> marsh<br />

vegetation. Here the Shalotte Inlet, in<br />

Brunswick County between Ocean Isle <strong>and</strong><br />

Holden Beaches, drains into Long Bay.<br />

Note the development on the bottom right<br />

<strong>of</strong> the photo. (Photo by Robert E. Reiman)<br />

51

Box 3A: Creeping, Climbing<br />

Kudzu.<br />

You are warned not to nap beside a southern roadside<br />

in summertime, or you might be covered in kudzu when you<br />

awake. There is a house in Chatam County obscured by the<br />

leafy vine, as well as a gas station in Dunn (Raleigh News<br />

<strong>and</strong> Observer 1997). Farm machinery <strong>and</strong> earth moving equipment<br />

are quickly covered by kudzu if left unattended.<br />

The U.S. Congress’ Office <strong>of</strong> Technology Assistance<br />

recently published a 390-page report on 4,500 species <strong>of</strong> exotic<br />

plants <strong>and</strong> animals that have been introduced into this<br />

country. The Associated Press quoted the project director as<br />

saying, “The economic <strong>and</strong> environmental impacts (<strong>of</strong> these<br />

exotic species) are snowballing...” Exotic species are those<br />

which have been relocated to a new environment. Many are<br />

transported accidentally, such as the tiger mosquito, which<br />

carries a virulent form <strong>of</strong> malaria. Others are brought purposefully<br />

for research, but are released accidentally, such as<br />

the African bee (killer bee). Often these exotic species are<br />

useful, but many become nuisances.<br />

One such plant species, kudzu, has been spreading<br />

across the southeastern U.S. for nearly 100 years, creating<br />

problems for farmers, foresters, telephone <strong>and</strong> power companies,<br />

<strong>and</strong> highway maintenance crews. It now covers more<br />

than two million acres <strong>and</strong> extends as far north as Illinois,<br />

Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania <strong>and</strong> New Jersey, <strong>and</strong> is still going.<br />

Its potential geographic range is as far north as Michigan,<br />

Wisconsin <strong>and</strong> the states <strong>of</strong> New Engl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Several kudzu vines typically sprout from a single<br />

deep-rooted stem, which may reach two to four meters (six<br />

to twelve feet) underground. The vines have wide,<br />

three-pronged leaves <strong>and</strong> short-lived purple flowers during<br />

the summer. As the vines creep across the l<strong>and</strong>scape, roots<br />

may enter the soil anywhere the stem touches the ground.<br />

Additionally, wherever the vines contact trees, they will attach<br />

with root-like appendages <strong>and</strong> begin to climb. Because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the stem’s ability to “take root,” highway-mowing operations<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten help spread this plant to new sites by dragging<br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> vines into new areas.<br />

52

The plant evolved in the Orient, probably in China.<br />

Kudzu has been cultivated in China, Korea <strong>and</strong> Japan for<br />

1,000 or more years because <strong>of</strong> its hardiness <strong>and</strong> its usefulness<br />

as food, fibers <strong>and</strong> medicines. It was initially brought to<br />

the U.S. in the late 1800s as a decorative ornamental for<br />

porches <strong>and</strong> walls. Advertised as livestock feed well into the<br />

1930s <strong>and</strong> ’40s, kudzu was <strong>of</strong>ten promoted by the leading<br />

l<strong>and</strong> grant universities <strong>and</strong> agriculture schools in the Southeast.<br />

During the Depression, highway departments across the<br />

Southeast used kudzu to control erosion along road cuts or<br />

where roads were cut into hillsides. Today, across the Southeast,<br />

the largest <strong>and</strong> oldest expanses <strong>of</strong> kudzu follow the roads<br />

that were built during this period.<br />

Kudzu does have some positive qualities, though they<br />

are limited. As a l<strong>and</strong> cover, particularly where soil is poor<br />

<strong>and</strong> erosion prone, kudzu quickly covers the raw earth. Furthermore,<br />

the roots <strong>of</strong> kudzu nurture nitrogen-fixing bacteria<br />

that remove nitrogen from the air <strong>and</strong> place it in the soil.<br />

Although livestock will graze on the young leaves <strong>of</strong> kudzu<br />

in the spring, most will eat almost any other plant in preference.<br />

Only goats <strong>and</strong> hogs seem to truly thrive on kudzu foliage.<br />

The negative qualities <strong>of</strong> kudzu greatly overshadow the<br />

positive ones. Perhaps the most troublesome trait is the speed<br />

<strong>of</strong> the plant’s growth. Growth rates <strong>of</strong> six to twelve<br />

inches per 24-hour period are common. The plant’s rapid<br />

growth <strong>and</strong> canopy <strong>of</strong> foliage make it extremely competitive<br />

with virtually all other natural plant species; it even climbs,<br />

<strong>and</strong> kills, fully grown trees, particularly pines.<br />

Strong herbicides are not very effective in killing a mature<br />

kudzu plant. Since many roots enter the ground from<br />

various points along the stem, spraying <strong>of</strong> herbicides is seldom<br />

totally effective. Researchers at North Carolina State<br />

University are working to engineer some type <strong>of</strong> kudzu-eating<br />

bugs that they can safely introduce into the environment.<br />

It might be a bio-engineered soybean looper, a small hairless<br />

caterpillar, with an appetite enhanced for devouring kudzu<br />

(Raleigh News <strong>and</strong> Observer, 1997).<br />

Although kudzu is used to produce fibers, medicines,<br />

<strong>and</strong> foods in the Orient, few such aspects <strong>of</strong> the plant are<br />

utilized in the U.S. Most North Carolinians consider it a weed<br />

<strong>of</strong> the most terrible variety <strong>and</strong> treat it accordingly. Perhaps<br />

the best one can say about kudzu is that it has been the subject<br />

<strong>of</strong> numerous good jokes. One disenchanted former promoter<br />

<strong>of</strong> kudzu, in comparing the vine to his favorite dog,<br />

wrote, “It was like discovering Ole Blue was a chicken killer.”<br />

Modified from <strong>Geography</strong> in the News #261, Neal G. Lineback,<br />

Appalachian State University, October 22, 1993. Photos by Ole<br />

Gade.<br />

53

the l<strong>and</strong>scape to mark its advances. As recently as 18,000 years<br />

ago, the shoreline would have been many kilometers east <strong>of</strong><br />

where it is today (Figure 1.8).<br />

Great natural diversity exists within the Coastal Plain. Most<br />

<strong>of</strong> the states wetl<strong>and</strong>s - bald cypress swamps, deep peat bogs,<br />

freshwater marshes <strong>and</strong> the mysterious Carolina bays - occur in<br />

the Coastal Plain <strong>and</strong> Tidewater regions. Historically, the upl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Coastal Plain were covered in longleaf pines <strong>and</strong><br />

scrubby oaks (Photo 3.8). Altered by natural <strong>and</strong> frequent fires<br />

through the centuries, Coastal Plain habitats have a rich diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> plant <strong>and</strong> animal communities adapted to fire. S<strong>and</strong>hills<br />

longleaf pine forest is most notable in this respect. So common<br />

was fire that plants <strong>and</strong> animals developed many adaptations to<br />

resist, avoid, or even take advantage <strong>of</strong> it. Bottoml<strong>and</strong> hardwood<br />

forests, longleaf pine savanna, pocosin, <strong>and</strong> the unique Carolina<br />

Bays (Box 1D <strong>and</strong> Figure 11.6) cover other parts <strong>of</strong> the Coastal<br />

Plain (Early 1993).<br />

Coastal Plain <strong>Vegetation</strong><br />

The vegetation <strong>of</strong> this region also shows the impact <strong>of</strong><br />

human activity. Early settlement resulted in wide spread clearing<br />

for agriculture that produced a fine mosaic <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> cover. In<br />

recent decades many holdings have been consolidated, with additional<br />

l<strong>and</strong> being cleared <strong>and</strong> drained for large scale farming<br />

operations, while other areas show extensive reforestation <strong>of</strong><br />

pine for pulp <strong>and</strong> paper production. Of particular interest are the<br />

vast deposits <strong>of</strong> peat which underlie the Pamlico Peninsula, “fossil”<br />

swamp vegetation from eight to nine thous<strong>and</strong> years ago<br />

that may have great promise as an alternative source <strong>of</strong> energy.<br />

Its use, however, would have great environmental consequences.<br />

The physical setting <strong>of</strong> the Coastal Plains is generally favorable<br />

for vegetative growth, as a long frost-free season, ample<br />

moisture, good soils, <strong>and</strong> flat terrain characterize the region. Plant<br />

diversity is encouraged by differences in drainage conditions,<br />

depth to water table, soil types, <strong>and</strong> frequency <strong>of</strong> fire. Welldrained<br />

but moist sites <strong>of</strong> the Inner Coastal Plain have finely<br />

textured soils <strong>and</strong> are generally covered with an oak-hickory<br />

<strong>and</strong> loblolly pine forest similar to that in the adjacent Piedmont.<br />

However, coarsely textured soils <strong>of</strong> the S<strong>and</strong>hills area as well as<br />

the extreme southeast coast have open st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> longleaf pine,<br />

an understory <strong>of</strong> scrub oaks, <strong>and</strong> a ground cover <strong>of</strong> wire grass.<br />

Longleaf pines develop deep taproots during the first three years<br />

<strong>of</strong> growth, while a grass-like cluster <strong>of</strong> needles at ground level<br />

withst<strong>and</strong>s the frequent fires. Then a rapid growth <strong>of</strong> its stem<br />

places needles <strong>and</strong> branches high enough to avoid fire damage.<br />

If fire were controlled, an oak hickory forest would soon replace<br />

the pines. Although fire destroys valuable timber, particularly<br />

in the southern Coastal plain, it can also be an important<br />

tool in managing the forest.<br />

Floodplains along the river courses support two types <strong>of</strong><br />

swamp forest. First, is a gum-cypress forest with high organic<br />

peaty soil that is almost continually under water. The second<br />

forest type is a broadleaf mixture <strong>of</strong> water oak, willow oak, sweet<br />

gum, ash, elm, sycamore, <strong>and</strong> river birch where soils usually<br />

dry out in summer months. An unusual wetl<strong>and</strong> vegetation, restricted<br />

to the North Carolina lower Coastal Plain, is known as<br />

“pocosin” from the Indian description “swamp on a hill” (Figure<br />

10.6). The pocosin evolved from the tidal sound environment<br />

as the coast was rising or as the sea receded. First, a swamp<br />

forest <strong>of</strong> cypress <strong>and</strong> gum developed; later, as thick deposits <strong>of</strong><br />

organic matter accumulated, soils became highly acid <strong>and</strong> deficient<br />

in nutrients. Fires occurred frequently until only a sparse<br />

growth <strong>of</strong> pond pine <strong>and</strong> dense shrubs was left. Similar vegetation<br />

dominates the Carolina Bays, elliptical depressions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

southern Coastal Plain (Box 1D).<br />

Occupying the flat areas between river courses in the southern<br />

Coastal Plain is savanna vegetation <strong>of</strong> pine flat woods.<br />

Coarser soils nurture a scattering <strong>of</strong> longleaf pine, a continuous<br />

ground cover <strong>of</strong> grasses, <strong>and</strong> a wide variety <strong>of</strong> wild flowers.<br />

Finer soils that are poorly drained support st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> pond pine<br />

as well as the endemic Venus flytrap, found only in southeastern<br />

North Carolina! Again we find that frequent fires perpetuate this<br />

savanna area; otherwise shrubs <strong>and</strong> trees would naturally succeed.<br />

Photo 3.8: The Cape Fear River, as it flows through<br />

Harnett County in the Coastal Plain Region’s far<br />

western edge, has a mix <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> uses. The river<br />

bank is still forested, but encroachment <strong>of</strong> homes<br />

near a golf course communtiy is beginning.Note<br />

the gentle rapids on the southern section <strong>of</strong> the river.<br />

(photo by Robert E. Reiman)<br />

54

Piedmont Habitat<br />

Early settlers used the term “Piedmont”, meaning “foot<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mountain”, to refer to this region west <strong>of</strong> the fall line <strong>and</strong><br />

east <strong>of</strong> the Blue Ridge Mountains, because its s<strong>of</strong>tly rolling hills<br />

reminded them <strong>of</strong> their foothills homes in Europe. As rivers <strong>and</strong><br />

streams flow across the fall line, it is the resistant crystalline<br />

rocks that form the rapids <strong>and</strong> small waterfalls (as the river erode<br />

the less resistant sedimentary materials below) (Early 1993).<br />

Of all the regions in the state, the Piedmont has been most<br />

densely settled. Although the clay soils disappointed early settlers,<br />

the fast flowing rivers provided power for grist <strong>and</strong> textile<br />

mills <strong>and</strong> industry grew rapidly. Most <strong>of</strong> the state’s urban centers<br />

<strong>and</strong> population are located in the Piedmont, <strong>and</strong> it is the<br />

most important economic region <strong>of</strong> the state (Early 1993).<br />

Much less is left <strong>of</strong> the Piedmont’s natural communities<br />

than those <strong>of</strong> any other region in the state because the original<br />

mixed pine <strong>and</strong> hardwood forests were cut <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong> was<br />

farmed by the Europeans <strong>and</strong> by the native Americans before<br />

them. Topsoil has been denuded by decades <strong>of</strong> poor farming<br />

practices. As the farms became less productive, they <strong>of</strong>ten were<br />

ab<strong>and</strong>oned <strong>and</strong> succeeded by forests (CP 3.5, 3.6, 3.7) (Early<br />

1993).<br />

Piedmont <strong>Vegetation</strong><br />

A fine mosaic <strong>of</strong> forest <strong>and</strong> cultivated l<strong>and</strong> indicates the<br />

impact that people have had on vegetation in the Piedmont. Early<br />

settlers found a continuous oak-hickory forest on well-drained<br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> a mixture <strong>of</strong> broadleaf species on the floodplains.<br />

As l<strong>and</strong> was cleared for agriculture <strong>and</strong> subsequently ab<strong>and</strong>oned,<br />

the growth <strong>of</strong> pines was favored. Pines dominate early stages <strong>of</strong><br />

natural succession, requiring much light <strong>and</strong> developing as an<br />

even-aged st<strong>and</strong>. However, they will eventually be replaced by<br />

broadleaf species if left unmanaged. The need for lumber <strong>and</strong><br />

pulpwood has enabled pines to dominate much <strong>of</strong> the Piedmont<br />

through forestry practices.<br />

Virginia pine occupies the western <strong>and</strong> northern sections<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Piedmont, short leaf pines the central section, <strong>and</strong> loblolly<br />

pine the eastern section <strong>of</strong> the Piedmont (CP 3.8). Soil <strong>and</strong> topographic<br />

differences account for the variety <strong>of</strong> hardwood species.<br />

Fertile, upl<strong>and</strong> sites favor southern red oak, white oak, <strong>and</strong><br />

mockernut hickory. A colorful under-story <strong>of</strong> dogwood <strong>and</strong> sourwood<br />

is common. Dry sites with thin soils support post oak,<br />

scarlet oak, <strong>and</strong> shagbark hickory. Sycamore, sweet gum, tulip<br />

poplar, willow oak, river birch, elm, <strong>and</strong> ash are common to<br />

floodplain areas. Some remnants <strong>of</strong> the mountain flora such as<br />

hemlock, white pine, <strong>and</strong> rhododendron occur in cool or elevated<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> the Piedmont, as is the case with Hanging Rock in Stokes<br />

County.<br />

Mountain Habitat<br />

The region <strong>of</strong> l<strong>of</strong>ty mountains from the Blue Ridge to the<br />

Tennessee border has the highest peaks <strong>and</strong> the greatest concentration<br />

<strong>of</strong> high elevations in the Southern Appalachians. National<br />

Forests cover vast expanses <strong>of</strong> the region <strong>and</strong> include the Pisgah<br />

<strong>and</strong> Nantahala. Great Smoky National Park also adds to these<br />

forest reserves. It is a region <strong>of</strong> spectacular waterfalls <strong>and</strong> gorges,<br />

with varying amounts <strong>of</strong> precipitation in the form <strong>of</strong> rain, mist,<br />

<strong>and</strong> snow (see Chapter 2). Trickling down from higher elevations<br />

are innumerable cold-water streams sheltering trout <strong>and</strong><br />

other aquatic life (Early 1993).<br />

The Mountain Region has a rich diversity <strong>of</strong> habitats, from<br />

rare bogs, to cove forests, to spruce-fir forests on the higher<br />

mountaintops. There are nearly 1,400 species <strong>of</strong> flowering plants<br />

in the region, including 85 native tree species (Early 1993).<br />

Mountain <strong>Vegetation</strong><br />

The Mountain Region displays two major types <strong>of</strong> vegetation,<br />

a broadleaf deciduous forest (CP 3.9, 3.10), at elevations<br />

up to 1,524 meters (5,000 feet), <strong>and</strong> a needle leaf evergreen<br />

forest or spruce-fir forest above that elevation (CP 3.11,<br />

3.12, 3.13). Also referred to as a boreal (northern) coniferous<br />

(cone-bearing) forest, this latter type resembles the vegetation<br />

<strong>of</strong> central Canada or the spruce-fir forests <strong>of</strong> New Engl<strong>and</strong> with<br />

red spruce <strong>and</strong> Fraser fir as dominant species. Fir is found on<br />

the highest exposed ridges <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten develops a banner or<br />

“krumholz” (twisted tree) form caused by the exposure to the<br />

prevailing winds <strong>and</strong> to ice breakage. Extensive logging, fires<br />

<strong>and</strong> wind-throw have allowed growth <strong>of</strong> mountain ash, fire cherry<br />

<strong>and</strong> yellow birch. While the spruce-fir forest has declined dramatically<br />

in recent decades due to environmental changes that<br />

are poorly understood.<br />

On steep, south-facing gaps, a deciduous forest <strong>of</strong> beech,<br />

yellow birch, <strong>and</strong> sugar maple known as “northern hardwoods”<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten replaces the spruce-fir forest that is more sensitive to windthrow.<br />

However, the deciduous forest is best developed at lower<br />

elevations where conditions are ideal for large <strong>and</strong> dense growth.<br />

Cove forests contain a great variety <strong>of</strong> species including tulip<br />

poplar, yellow buckeye, cucumber tree, hemlock, white pine,<br />

beech, birch <strong>and</strong> maple. Rosebay rhododendron reaches tree size<br />

in some areas. On drier, exposed south-facing slopes, oaks dominate<br />

the forest, replacing the original American chestnut which<br />

covered up to eighty percent <strong>of</strong> the area before a blight was<br />

introduced in the mid-1920s. Various species <strong>of</strong> oak have different<br />

environmental needs <strong>and</strong> migrate towards elevation zones.<br />

Northern red oak dominates from 1,524 to 1,220 meters (5,000<br />

to 4,000 ft), chestnut oak from 1,220 to 915 meters (4,000 to<br />

3,000 ft), <strong>and</strong> white oak below 915 meters (3,000 ft). On most<br />

steep south or southwest-facing slopes <strong>and</strong> on dry open ridges<br />

pines <strong>and</strong> black locust are dominant, with mountain laurel <strong>and</strong><br />

blueberry providing a dense scrub layer. Fires <strong>and</strong> thin soils encourage<br />

this community to develop.<br />

The entire Mountain Region is not characterized by forest<br />

cover; in some places treeless “balds” have developed. A thick<br />

growth <strong>of</strong> mountain laurel <strong>and</strong> rhododendron or a cover <strong>of</strong> mountain<br />

oat grass dominate balds. How the balds are caused is not<br />

completely understood. Most likely they are due to a combina-<br />

55

tion <strong>of</strong> fire, windfall, <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>slides, along with human activities<br />

such as hunting <strong>and</strong> grazing <strong>of</strong> cattle. For many years in the<br />

early part <strong>of</strong> this century, it was a common practice to bring in<br />

cattle from the Tennessee valley to the west, fatten them on high<br />

mountain pastures during the summer, <strong>and</strong> then send them to<br />

the Piedmont for slaughter in the fall. It is said that the community<br />

<strong>and</strong> township <strong>of</strong> Meat Camp in Watauga County derived its<br />

name from that practice.<br />

WILDLIFE<br />

A variety <strong>of</strong> mammals, birds, <strong>and</strong> fish live within our l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

Given the state’s varying habitats, one finds an abundance<br />

<strong>of</strong> wildlife present throughout the state. As our l<strong>and</strong>scape is<br />

modified by spreading urbanization, reservoir construction <strong>and</strong><br />

other environment altering activities, our wildlife must adapt to<br />

survive or migrate to more appropriate habitats. However, not<br />

all wildlife adapts easily so while one species may flourish, others<br />

may suffer. Outdoor recreational pursuits include hunting,<br />

fishing, <strong>and</strong> boating. Protection <strong>of</strong> wildlife habitat from the<br />

marshes <strong>of</strong> the Tidewater to the forests <strong>of</strong> the Mountain Region<br />

is critical.<br />

Mammals<br />

Our state mammal is the gray squirrel. Squirrels seem abundant,<br />

as they appear plentiful in any city park on a spring day.<br />

However, the population <strong>of</strong> gray squirrel has been dwindling as<br />

hardwood forests, the best squirrel habitat, has been slowly converted<br />

through the years into pine forests. Squirrels adapt to many<br />

habitats, but do not always thrive in them. Adaptation is crucial.<br />

Rabbit numbers are also down as farmers eliminate brush piles<br />

<strong>and</strong> wooded lots for crops. Pesticide <strong>and</strong> herbicide uses that cause<br />

pollution are another factor effecting squirrel <strong>and</strong> rabbit populations.<br />

In 1910 deer populations numbered 10,000, in 1970 they<br />

numbered 300,000 <strong>and</strong> it has since more than tripled to 900,000<br />

in 1997 (Charlotte Observer 1999). What is the cause <strong>of</strong> the<br />

increase? Figure 3.7 illustrates the deer population <strong>and</strong> distribution.<br />

Simply stated, deer are very adaptable creatures. North<br />

Carolina’s checkerboard l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>of</strong> forests, pastures, farms,<br />

developments, marshes, <strong>and</strong> water create a habitat in which deer<br />

can survive <strong>and</strong> thrive. Edge environments are critical to deer<br />

habitat. Great diversity <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> cover provides this edge environment<br />

<strong>and</strong> is better for deer. Yet, it is clear from 3.7 that deer<br />

habitats gradually improve from west to east.<br />

Black bear, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, require large expanses <strong>of</strong><br />

swamp or forests to survive (Figure 3.8). Compare the distribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> the bear populations with the pattern <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> cover (CP<br />

1.14). Note that the largest concentrations <strong>of</strong> black bear are found<br />

in the Coastal Plain <strong>and</strong> Mountain regions. Development, such<br />

as vacation homes, golf courses, <strong>and</strong> roads are diminishing the<br />

56<br />

Figure 3.7: White-Tailed Deer Harvest, 1998-99.<br />

Source: North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission, 1999.

Figure 3.8: Black Bear Kill, 1998-99.<br />

Source: North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission, 1999.<br />

Figure 3.9: Coyote Diffussion, 1988-1997.<br />

Source: Modified from the Charlotte Observer, 1999.<br />

bear’s habitat. While changing l<strong>and</strong>scape may provide useful<br />

habitat to one mammal, others may suffer or approach extinction.<br />

Coyotes have been sighted in our state, from the Tidewater<br />

to the Mountain regions. Figure 3.9 illustrates the spread or<br />

diffusion <strong>of</strong> coyotes throughout North Carolina. If this trend<br />

continues, coyotes will soon be present in every county.<br />

Beaver were abundant in the earlier years <strong>of</strong> settlement,<br />

were eradicated, were reintroduced in the 1940s, <strong>and</strong> today beaver<br />

are common in much <strong>of</strong> the state (Figure 3.10). It is not<br />

uncommon to see a beaver dam in the small northwestern mountain<br />

community <strong>of</strong> Beaverdam in Watauga County.<br />

Other recent reintroduction programs for mammals have<br />

been accomplished. These efforts have included the red wolf,<br />

which has been successfully reintroduced in the Tidewater region<br />

(Figure 3.11), while attempts to stabilize a population in<br />

the Smoky Mountains have failed. Road densities <strong>and</strong> road pattern<br />

seem to have a direct impact on the success <strong>of</strong> this reintroduction<br />

program. Roads create edge habitats that are a crucial<br />

source <strong>of</strong> food for the red wolf. The otter has been reintroduced<br />

to the western part <strong>of</strong> the state after they were forced to the eastern<br />

Piedmont <strong>and</strong> Coastal Plain regions, because <strong>of</strong> diminishing<br />

expanses <strong>of</strong> quality habitat.<br />

Wild boar were introduced to North Carolina in 1912, as<br />

14 European wild boars were released in a game preserve on<br />

Hooper’s bald in Graham County. After escaping from the preserve<br />

the wild boar established occupied ranges in some mountain<br />

counties (Figure 3.12). The first open hunting season was<br />

in 1936, <strong>and</strong> in 1979 the North Carolina Legislature designated<br />

the status <strong>of</strong> game animal to the wild boar. Figure 3.13 reflects<br />

the number <strong>and</strong> location <strong>of</strong> wild boar harvested during the 1998-<br />

99 hunting season (North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission<br />

1999).<br />

Wild horses <strong>of</strong> the Outer Banks have been allowed to roam<br />

the range <strong>of</strong> a remote Carteret County isl<strong>and</strong> for decades <strong>and</strong><br />

they have thrived there. In 1995, an estimated 225 horses grazed<br />

the eight-mile long Shackleford Banks (part <strong>of</strong> the Cape Lookout<br />

National Seashore). Their populations have increased since<br />

sheep, goats, <strong>and</strong> cattle were removed in the mid-1980s, when<br />

the Park Service took over the l<strong>and</strong> for the national seashore.<br />

Concern for the horses has heightened as their increasing population<br />

has placed great stress on the habitat. Grasses that once<br />

grew to knee height are now eaten close to the ground level.<br />

Officials fear that food supplies will continue to dwindle <strong>and</strong><br />

horses may starve <strong>and</strong> die <strong>of</strong>f as they have on Carrot Isl<strong>and</strong> near<br />

Beaufort.<br />

Figure 3.10: Beaver Distribution, 1999.<br />

Source: North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission, 1999.<br />

Figure 3.11: Red Wolf Distribution.<br />

Source: United States Fish <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service, 1999.<br />

57

Figure 3.12: Wild Boar Distribution, 1999.<br />

Source: North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission, 1999.<br />

Wild turkeys, with populations dwindling, were reintroduced<br />

through an active (3,565 birds since 1970) <strong>and</strong> somewhat<br />

costly restocking program (about $500 per restoration bird). Now<br />

the turkeys are flourishing. Populations have experienced dramatic<br />

increases since this program began. Only 2,500 birds existed<br />

in North Carolina in the early 1960s. Numbers increased<br />

to 7,500 in 1980, then to 28,000 in 1990, <strong>and</strong> in 1996 turkeys<br />

numbered more than 86,000 (Charlotte Observer 1996). Herds<br />

<strong>of</strong> over 100 birds have been seen in Watauga <strong>and</strong> Ashe Counties<br />

(CP 5.19). In North Carolina 95 <strong>of</strong> the 100 counties have wild<br />

turkey populations (Figure 3.14). Wild turkeys provide a popular<br />

game bird during the fall season, as hunters work their distinctive<br />

calls <strong>of</strong> gobbling in hopes <strong>of</strong> attracting a bird. As will be<br />

seen in Chapter 5, the domesticated cousin <strong>of</strong> this bird has also<br />

contributed to the state economy. North Carolina is the number<br />

one turkey producer in the nation. Hunters also find the morning<br />

dove a popular game bird, though this bird along with grouse<br />

<strong>and</strong> quail have experienced declines.<br />

Bald eagles have made a comeback since the banning <strong>of</strong><br />

DDT. Only one nesting site was known in the state in 1972; in<br />

1995, there were 12 known sites <strong>and</strong> in early 1999 there are<br />

over 20 sites. Seven breeding pairs were in the northeastern part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the state, nesting in Pasquotank, Chowan, Washington, Hyde,<br />

Beaufort, Tyrrell, <strong>and</strong> Dare counties (Raleigh News & Observer<br />

1995). North Carolina, South Carolina, <strong>and</strong> Virginia have made<br />

intensive efforts to increase the population <strong>of</strong> our nation’s sym-<br />

Figure 3.13: Wild Boar Harvest, 1998-99.<br />

Source: North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission, 1999.<br />

Birds<br />

A multitude <strong>of</strong> song birds find habitat in our state, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

cardinal is designated as our state bird. However, as the large<br />

forested areas dwindle, so do the populations <strong>of</strong> the birds that<br />

need this habitat to thrive. Over the past 25 years, nearly 20<br />

species <strong>of</strong> bird populations have declined. The loggerhead shrike,<br />

a forest dwelling bird, is down 95 percent, while meadowlarks,<br />

mockingbirds, <strong>and</strong> blue jays are down 53, 45, <strong>and</strong> 38 percent<br />

respectively. At the same time, bluebirds have increased 369<br />

percent; cowbirds, 301 percent; <strong>and</strong> robins, 75 percent; these<br />

birds favor forest edges, which are created or enhanced with<br />

road cuts <strong>and</strong> construction (Charlotte Observer 1990).<br />

Figure 3.14: Wild Turkey Harvest, 1998.<br />

Source: North Carolina <strong>Wildlife</strong> Resources Commission, 1999.<br />

bol; unless people interfere again, the eagles are back to stay.<br />

Not as lucky as the eagle is the red-cockaded woodpecker,<br />

a bird heading toward possible extinction. In 1989, Hurricane<br />

Hugo ripped through the nations second largest population in<br />

the Francis Marion National Forest in South Carolina. About<br />

450 birds died <strong>and</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the rest were left without viable habitat.<br />

Now work is continuing to restablish a viable habitat in the<br />

S<strong>and</strong>hills (see Chapter 11). <strong>Natural</strong> disasters can have a dramatic<br />

impact on habitat quality: hurricanes devastate large areas<br />

while the tornadoes impact a much smaller area (Chapter 2).<br />

Fish <strong>and</strong> Turtles<br />

Fresh <strong>and</strong> saltwater fish provide a valuable economic <strong>and</strong><br />

recreational resource for our state. Our shores are blessed with<br />

barrier isl<strong>and</strong>s, hundreds <strong>of</strong> miles <strong>of</strong> inl<strong>and</strong> shoreline, sounds<br />

<strong>and</strong> estuaries, all providing habitat for a diverse saltwater fish<br />

population. Inl<strong>and</strong>, the surface waters <strong>of</strong> our state provide many<br />

excellent recreational opportunities as well (see Chapter 10).<br />

Over-fishing <strong>and</strong> dams have reduced the striped bass fisheries<br />

in the Coastal Plain region. However, in mountain rivers<br />

reintroduced muskies have made a comeback since the removal<br />

<strong>of</strong> some dams (Charlotte Observer 1990).<br />

Trout, which are abundant in many <strong>of</strong> the state’s rivers,<br />

suffer because <strong>of</strong> increasing development near their habitat. De-<br />

58

velopment activities may release sediment that flows into<br />

streams; this process <strong>of</strong> sedimentation can kill trout. Road, resort,<br />

<strong>and</strong> golf course development, if done improperly, devastates<br />

trout stream quality. Additionally, the clearing <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

which once shaded the waters <strong>and</strong> kept them cold are no longer<br />

there to protect the water from warming by the sun. Increasing<br />

the temperature <strong>of</strong> the water decreases the trout population. Agricultural<br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> fertilizering compounds in streams<br />

through run<strong>of</strong>f will also decrease water quality.<br />

Loggerhead turtles find the shores most suitable for nesting<br />

from May through August. These turtles have found it increasingly<br />

difficult to thrive in the rapidly developing coastal<br />

areas. Representatives at Brunswick County’s Turtle Watch Program<br />

estimate that only about 100 turtles reach adulthood for<br />

every 7,000 eggs laid. Newborn turtles are attracted to the brightest<br />

lights; years ago that light was moonlight, which lead them<br />

to the ocean. However, lights from nearby modern development<br />

attract the newborn turtles inl<strong>and</strong> to their demise. Predators such<br />

as raccoons, snakes, <strong>and</strong> ants also find the turtle’s eggs a tasty<br />

food source.<br />

59

Orange<br />

North Carolina’s Place<br />

in the World<br />

CANADA<br />

U N<br />

I T E<br />

S T A T E S<br />

D<br />

North Carolina’s<br />

Place in the<br />

United States<br />

MEXICO<br />

Currituck<br />

Camden<br />

Physiographic Regions<br />

<strong>and</strong> Counties <strong>of</strong><br />

North Carolina<br />

Mountain Region<br />

Piedmont Region<br />

Coastal Plain Region<br />

Tidewater Region<br />

Iredell<br />

Surry Stokes<br />

Yadkin<br />

Rowan<br />

Cabarrus<br />

Stanly<br />

Union Anson<br />

Richmond<br />

Montgomery<br />

Moore<br />

Mecklenburg<br />

Harnett<br />

Halifax<br />

Northampton<br />

Edgecombe<br />

Pitt<br />

Hertford<br />

Bertie<br />

Martin<br />

Gates<br />

Pasquotank<br />

Chowan<br />

Hoke<br />

Person<br />

Brunswick<br />

Nash<br />

Durham<br />

Robeson<br />

Wake<br />

Johnson<br />

Sampson<br />

Bladen<br />

Columbus<br />

Franklin<br />

Warren<br />

Alamance<br />

Granville<br />

Vance<br />

Cherokee<br />

Graham<br />

Clay<br />

Swain<br />

Macon<br />

Haywood<br />

Jackson<br />

Madison Yancey<br />

Buncombe<br />

Henderson<br />

Polk<br />

Avery<br />

McDowell<br />

Rutherford<br />

Burke<br />

Ashe<br />

Caldwell<br />

Alleghany<br />

Watauga Wilkes<br />

Rockingham<br />

Transylvania<br />

Alex<strong>and</strong>er<br />

Davie<br />

Forsyth<br />

Davidson<br />

Perquimans<br />

Cumberl<strong>and</strong><br />

Scotl<strong>and</strong><br />

Guilford<br />

R<strong>and</strong>olph<br />

Caswell<br />

Mitchell<br />

Catawba<br />

Lincoln<br />

Gaston<br />

Chatham<br />

Lee<br />

Wilson<br />

Wayne<br />

Duplin<br />

Pender<br />

Greene<br />

Lenoir<br />

New<br />

Hanover<br />

Jones<br />

Onslow<br />

Craven<br />

Beaufort<br />

Pamlico<br />

Carteret<br />

Tyrell<br />

Hyde<br />

Dare<br />

Clevel<strong>and</strong><br />

Color Plate 1.1: North Carolina’s World, Regional, <strong>and</strong> Local Settings.<br />

61