Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

N E W SColor returns to Amiens Cathedral inFrance. Following a restorative cleaningin 1992, traces of color were found inthe recesses of façade sculptures that dateback 800 years. Seen as too invasive, reapplyingpaint was rejected, but the effect ofcolor has been achieved instead with lighting.Paris-based designers Skertzo havematched the original pigments in lightand found a way to project them onto thesculptures. <strong>The</strong> colored façade can be seeneach evening from June to September andduring the winter holidays.Amiens Cathedral, FranceAccording to Elvira Obenbach, “a churchis not a museum but the house of God.”Covering 100 churches, convents, andhouses of Rome, Obenbach’s book In theFootprints of the Saints of Rome: Guide to theIcons, Relics and Houses of Saints encouragesthe spiritual discovery of Rome beyond theartistic. “This guide is to fill a lacuna andto lead a pilgrim not to the artistic work butin the footprints of the saints and blessed,”writes the author. She also says, “It is goodto remind the public that art is a support,not the essence.” Vatican Press is the publisherof her new book. See www.libreriaeditricevaticana.com.Neocatechumenal Way opens a chapel onthe Mount of the Beatitudes. In Tiberias,Israel, the design <strong>for</strong> the Domus GalilaeaeInternational Center, originally conceivedby Spanish painter Kiko Arguello withCarmen Hernandez and a group of internationalarchitects, will serve as a “bridgewith the whole Jewish tradition.” <strong>The</strong> designof the 12,000-square-meter complex,which slopes toward Lake Tiberias andspans three terraces, houses a multitudeof spaces from a congressional center anda church to guest rooms. <strong>The</strong> complex invitesChristians to return to Jewish sourcesto understand the meaning of the Jewishprayers and liturgical celebrations that dailysustained Jesus.Photo: Architectural Record, Nov, 2003Holy Transfiguration, Skete, an EasternCatholic monastery on the shore of LakeSuperior, adapts traditional Ukrainian designelements typical of country churches inthe Carpathians to contemporary needs ina new building project. Designed by PageOnge of Nashville, Tennessee, the 4,500-square-foot monastery is of conventionalwood framing and clad with sawn shinglesof local cedar. Consecrated on August 24,2003, by the Most Reverend Steven Seminack,Eparch of St. Nicholas in Chicago, theByzantine monastery also boasts of severalanodized aluminum domes. For more in<strong>for</strong>mationsee www.societystjohn.com.Augustus Welby Pugin is being proposed<strong>for</strong> canonization by James Thunder, “Pugin:A Godly Man?” True Principles (Summer2002 and Summer 2003). Thunderfocuses on Pugin the man and not his architecture.He argues that, as with Gaudi,the canonization of an architect would notnecessarily canonize his architecture. Thunderexamines Pugin’s roles as husband, asfather to eight, as friend and colleague, aswell as Pugin’s response to adversity, hischarity, and above all the evangelical zealdemonstrated in his writings and work.<strong>The</strong> World Monuments Fund has releasedits 2004 watch list of the 100 mostendangered architectural sites. <strong>The</strong> WMFis a nonprofit organization that seeks topreserve the world’s historic, artistic andarchitectural heritage. Churches on thelist include St. Anne’s Church in Prague(which contains a series of Gothic, Renaissance,and Baroque Murals, as well as itsGothic truss system, despite its use as awarehouse <strong>for</strong> the last 200 years) and IglesiaSan Jose in San Juan, Puerto Rico (theoldest surviving building in Puerto Rico,as well as one of the earliest examples ofGothic-influenced architecture in the WesternHemisphere). See www.wmf.org.<strong>The</strong> Benedictine Monastery of the HolyCross has been founded in Rostrevor,Northern Ireland, as a sign of reconciliation.Five monks of the Congregation ofSt. Mary of Mount Olivet, coming from theAbbey of Bec in France, have <strong>for</strong>med thenew community in the interest of bringingthe Rule of St. Benedict back to Ireland.<strong>The</strong> foundation decree states: “Our particularmission is to contribute to reconciliationbetween Catholics and Protestants ina land marked by reciprocal violence andstained by the blood of Christian brothersand sisters.” See www.benedictinemonks.co.ukA cathedral in Nottingham, England,hopes to keep its doors open 24 hours aday. Police and social service personnelare now training volunteers to keep watchin St. Barnabas Cathedral. Approximately100 volunteers are needed to keep open the19th-century Gothic Revival cathedral byA.W. Pugin.Working collaboratively with the parishcommunity of St. Paul’s Episcopal Churchin Steamboat Springs, Colorado, Andersson-Wisearchitects trans<strong>for</strong>med an overcrowdedchurch into a massive new spacewhile retaining the intimate feel of the 1911original. Central to the design is an emphasison the verticality of the space to heightenthe parishioners’ sense of relationship withGod. According to Rev. David Henderson,the key of the project is “paying homage tothe tradition of the church without replicatingit.” <strong>The</strong> effect is an elegant monasticsimplicity <strong>for</strong> the new 250-person capacity21,000-square-foot church.White Chapel at Rose-Hulman <strong>Institute</strong>of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana,is designed by VOA as an ecumenicalchapel.Copenhagen’s Pentecostal Christianslook to “Catholic” symbols <strong>for</strong> inspiration.Until now Pentecostal Christiansin Denmark have avoided symbols suchas crosses or candles as being too RomanCatholic. However they are beginning torealize their potential as Rev. Rene Ottesenfrom Copenhagen’s biggest Pentecostalchurch stated: “We have lost the symbols,and there<strong>for</strong>e we have lost the hook onwhich to hang our faith.” He also added,“<strong>The</strong> symbols give a physical and tangibledimension to our faith.”Photo: Contract, Sept, 2003<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9 5

N E W S<strong>The</strong> Poor Clare Sisters of Barhamsville,Virginia celebrate the completion of their40,000-square-foot monastery on 42 acres.Statistics are explored to find the goldenera of American Catholicism. James Davidson,a professor of sociology at the Universityof Purdue, collected data from the“Official Catholic Directory” on aspects ofchurch life <strong>for</strong> five-year intervals between1930 and 2000. With less than half of itscurrent membership, Davidson found the1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s were institution-buildingyears in which the Church had morediocesan high schools (2,123), diocesanseminaries (202), and private high schools(1,394) than it has ever had. <strong>The</strong> 1960sbrought new highs in building with records<strong>for</strong> Catholic hospitals (808), religious orderseminaries (497), Catholic colleges anduniversities (304), and elementary schools(10,503). <strong>The</strong> number of parishes peakedin the 1990s (19,971) but has since declined.To sum his findings, the 1960s appear to bethe golden era, with 1965 being the peakyear.Hope fades <strong>for</strong> the preservation of St. StephenCatholic Church as a local historiclandmark in South Bend, Indiana. <strong>The</strong> 93-year-old church was closed in May of 2003and most of the building’s artifacts, includingits stained-glass windows, have beendonated or sold to other parishes. Whilethe Historic Preservation Commission statedthere was no question that the structurewould be eligible both architecturally andhistorically <strong>for</strong> landmark status, it has hesitatedto take action owing to the lack of anyproposals <strong>for</strong> how to take care of the buildingonce it ceases to be a church.“St. Peter and the Vatican: <strong>The</strong> Legacy ofthe Popes” is the largest collection of Vaticanartifacts ever to tour North America.<strong>The</strong> exhibit offers visitors a rare glimpseinto the 2,000-year history of the papacy asseen through the lens of 350 objects drawnfrom Vatican museums and archives, aswell as churches administered by the Vatican.This is the first time many of the objectshave ever left the Vatican or been onpublic display. “St. Peter and the Vatican”Photo Courtesy Poor Clare Sisterswill be at the San Diego Museum of ArtMay 15 through September 6, 2004. Formore in<strong>for</strong>mation, visit www.sdmart.org.Among the victims of the November 20,2003, suicide bombing on the British Consulatein Istanbul was the community ofthe Catholic-Chaldean Church. Unlessthe badly damaged church and offices arerenovated the community cannot resumeits activities. <strong>The</strong> German-based Aid to theChurch in Need is leading the ef<strong>for</strong>t to helpand is seeking benefactors <strong>for</strong> support.Visit www.kirche-in-not.org/e_home.htm.After 30 years, construction has resumedon a long unfinished church designed byinfluential modernist Le Corbusier. Begunin 1970, the Church of Saint-Pierre deFirminy-Vert (a suburb of Saint-Etienne,near Lyon) was designed as part of a projectintended to unite dwellings, spiritual life,culture, and sport in a single urban complex,but construction of the church halteddue to lack of funds. While the bottom halfhas been built, it will require a minimumof 17 months to rein<strong>for</strong>ce the structure,complete the interior, and build the shell ofthe edifice. <strong>The</strong> structure, which has neverbeen used as a church, will have a smallnon-denominational worship space, whilemost of the building will be an annex to theSaint-Etienne museum of modern art.Model of Le Corbusierʼs Church ofSaint-Pierre de Firminy-VertCali<strong>for</strong>nia’s missions are becoming endangereddue to lack of funding <strong>for</strong> preservation.<strong>The</strong> highest on the preservationlist is the closed mission of San Miguel inArcangel, which sustained further damagein last December’s earthquake. Though allof the missions receive the state’s historiclandmark status, there has been no statewideef<strong>for</strong>t on the mission’s behalf to fundraise<strong>for</strong> their preservation.Romanian Catholics are seeking supportfrom the European Union to regain parishproperties that were handed over toOrthodox caretakers during the rule of thecountry’s <strong>for</strong>mer Communist regime. SupportingRomania’s petition <strong>for</strong> entry intothe European Union, Bishop Virgil Berceaof Oradea has made a plea to the EuropeanCommission to place “the patrimonialproblems of the Romanian Greek-CatholicChurch” on the agenda in talks with thecurrent government. A Byzantine bodyin union with the Holy See, the RomanianCatholic Church was outlawed by theCommunist regime after WWII as propertieswere confiscated and members <strong>for</strong>cedto choose between attending Orthodox servicesor risking imprisonment.6 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9Photo: © FLC-ADAGPPope John Paul II calls <strong>for</strong> artists to reflectGod with their work. Speaking to a groupfrom the Artistic and Cultural FormationCenter from Poland, the Pope remarkedthat “in man, the artist, the image of theCreator is reflected. I say this also so that allpresent here are conscious that this reflectionof God implies a great responsibility.”<strong>The</strong> Holy Father continued, stressing thatone’s talent must be developed in order “toserve one’s neighbor and society with it.”He added, “Artists are responsible not only<strong>for</strong> the aesthetic dimension of the worldand of life but also of the moral dimension.If artists are not guided by good in creativity,or even worse, are led toward evil, theyare not worthy of the title of artist.”<strong>The</strong> sacrament of reconciliation goes mobilewith the blessing of a van in Augsburg,Germany. Supported by the Germansection of the International Catholic charityAid to the Church in Need, the confessionalon wheels will be used during events likeWorld Youth Day 2005 in Cologne and willalso offer a chance <strong>for</strong> people to speak to apriest and receive spiritual counseling.Grace Church in New York sells ad. spaceto banks and luxury-car companies on a140-foot billboard spanning its Gothic façade.Finding it difficult to generate the $2million funds needed <strong>for</strong> the restoration ofthe church, Rev. David M. Rider has had tolook <strong>for</strong> creative solutions to care <strong>for</strong> whathe calls a “high maintenance facility.” Designedby James Renwick, architect of St.Patrick’s Cathedral, Grace Church is a landmarkbuilding, which means it requires thehighest standards in restoration, while receivingno extra funds to follow such mandates.While the ads are temporary, architecturalhistorian Franz Schulze still comments,“It’s rather bad <strong>for</strong>m to smear yourname over a very beautiful church façade.”

N E W SMosaic within Redemptoris MaterChapel, Vatican<strong>The</strong> Vatican has established a website featuringthe recently renovated RedemptorisMater Chapel. <strong>The</strong> chapel was redecoratedwith mosaics inspired by the EasternChurch with money given to John Paul IIby the College of Cardinals in celebrationof the 50th anniversary of his priestly ordination.Designed to capture the theologicalessence of both east and west—“the twolungs of the Church”—the chapel is thesite of the Holy Father’s Lenten retreat. Seewww.vatican.va/redemptoris_mater/index_en.htm.<strong>The</strong> Boudreaux Group Inc. has completeda renovation <strong>for</strong> St. Peter’s CatholicChurch in Columbia, South Carolina.<strong>The</strong> work incorporates a carefully detailedwood floor and a new baptismal pool thatuses the original font. <strong>The</strong> use of color, murals,and gold leaf has also given new life tothe triumphant columns and vaults of thehistoric interior. According to the architectsevery ef<strong>for</strong>t was made to use the best of materialsand methods to honor this beautifulchurch.Archbishop Raymond L. Burke of St.Louis presided over the groundbreaking ofthe main church at the Shrine of Our Ladyof Guadalupe in La Crosse, Wisconsin, onThursday, May 13. <strong>The</strong> estimated cost ofthe project is $20 million and is expected totake two and a half years to complete.Controversy arose in Italy over a localjudge’s decision to order the removal ofcrucifixes from public school rooms. <strong>The</strong>controversy quieted as it was confirmed thata 1923 government decree, unaltered by theconcordat between Italy and the CatholicChurch in 1984, provides <strong>for</strong> crucifixes inItalian schools. Support <strong>for</strong> the crucifix camefrom both secular and religious communities.Giuseppe Vacca, current presidentof the Antonio Gramsci <strong>Institute</strong>, said thecrucifix goes beyond the boundaries ofChristianity and embraces the whole of humanityas well as <strong>for</strong>ming part of the Italianand European cultural identity. Pope JohnPaul II also noted that social cohesion andpeace are not achieved by eliminating thecharacteristic religiosity of a culture.<strong>The</strong> recently completed Prince of PeaceCatholic Church in Taylors, South Carolinagarnered a merit award from theGreenville, South Carolina AIA. Built byCraig Gaulden Davis, Inc., the $6.2 millionchurch uses contemporary materials toevoke traditional Catholic architectural archetypesof verticality and light. <strong>The</strong> newchurch seats 1,200 and features a limestoneambo placed so that the gospel is readamong the congregation.Prince of Peace Catholic ChurchTaylors, South CarolinaArtisan Henry Swiatek works to restoreSt. Stanislaus Church in Rochester,New York. Recreating the rich palette ofpainted art work that was destroyed in the1960s renovation that covered the churchin shades of beige, the Polish Americanartist takes a special interest in this church,which was established in 1890 by Rochester’sfirst Polish immigrants. Of all the restorativeef<strong>for</strong>ts, Swiatek’s have gained themost appreciation, with words of thanksand praise from the parishioners <strong>for</strong> givingthe community back “the full beauty ofthe church.”<strong>The</strong> Kate and Laurance Eustis Chapel <strong>for</strong>the Ochsner Clinic Foundation in NewOrleans, Louisiana provides a place ofserenity in an otherwise constant realm offlux. Designed by Eskew+Dumez+Ripplethe nondenominational chapel avoids religiousimagery, but relies on natural light,water features, and a creative use of materialsto provide a sense of calm and depthin a small space. <strong>The</strong> 1,000-square-footPhoto: © Brian Dressler Photographyspace provides a connection with the lobbythrough a stained glass window-wall andenvelops the visitor with a woven ceiling“shroud” made of 5,000 separate pieces ofwood.A Slovakian priest works to restore aCatholic parish in Briansk, Russia. Fr. JanHermanovsky said many “people in Russia,after the decades of materialism…[have] noidea of the sacred; they do not have the habitof prayer, and make no distinction betweengoing to Mass or to the theater.” Now goingto Russia to reopen the parish of Briansk,referring to the fact that the <strong>for</strong>mer churchhas been converted into apartments he said,“I have preferred to purchase a private house<strong>for</strong> purposes of worship. It still does nothave external signs characterizing it as achurch, but we will soon place the cross andan image of the Virgin on the façade.”A visit to Rome should include the “nobile”rooms of the Lateran Palace at the Basilicaof St. John Lateran. Now open to thepublic, the old papal residence rebuilt bySixtus V (1585-1590) includes a wealth ofartifacts from past papal households fromthe desk of Pius VII to the red velvet pagodaused to carry John XXIII. On a guidethrough the frescoed ten-room apartmentsFather Pietro Amato quoted Dante saying,“<strong>The</strong> Lateran is above earthly things.” Aticket to the Lateran Museum will now beincluded in the entrance fee to the VaticanMuseums.Emerging out of the post-Communist eraonly a decade ago, the Catholic communityin Mongolia now has a cathedral in UlanBator. Cardinal Crescenzio Sepe, prefect ofthe Congregation <strong>for</strong> the Evangelization ofPeoples, consecrated the cathedral. About200 faithful make up the Catholic communityof Mongolia out of a population of 2.7 millioninhabitants. Speaking on the historicalroots of Christianity in Mongolia CardinalSepe said, “This was possible only becausethe great Mongol khans … showed a typeof wisdom that was rare in the 13th century,namely, tolerance and acceptance of all religions.”<strong>The</strong> new cathedral is dedicated toSts. Peter and Paul.U.S. bishops encourage popular devotionsas a means to shape our culture. <strong>The</strong>bishop’s conference stated, “When properlyordered to the liturgy, popular devotionsper<strong>for</strong>m an irreplaceable function of bringingworship into daily life <strong>for</strong> people ofvarious cultures and times.” <strong>The</strong> bishopsalso emphasized the primacy of the liturgyin their document, writing, “Since the liturgy<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9 7

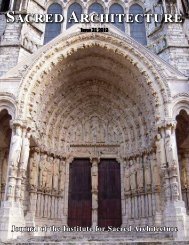

N E W Sis the center of the life of the Church, populardevotions should never be portrayed asequal to the liturgy, nor can they adequatelysubstitute <strong>for</strong> the liturgy. What is crucial isthat popular devotions be in harmony withthe liturgy, drawing inspiration from it andultimately leading back to it.”<strong>The</strong> Romanesque chapel of Our Ladyof the Assumption in Mystic, Connecticut,though new, gives the impression of“a sturdy spiritual beacon that has beenwatching over the boats on Fisher’s IslandSound <strong>for</strong> at least a century—maybe several.”Designed by Dennis Keefe of Boston,the chapel includes a host of liturgical artcrafted by artists associated with the St.Michael <strong>Institute</strong> of <strong>Sacred</strong> Art. As an islandchapel a nautical theme is prominentthroughout, especially in the pegged beamsof the ceiling recalling the inverted hull ofa ship. <strong>The</strong> Stations of the Cross, done asmedieval manuscript illuminations, rein<strong>for</strong>cethe local setting as the Passion unfoldswith important sites on the island <strong>for</strong>mingthe backdrop. For further in<strong>for</strong>mation visitwww.endersisland.com.Our Lady of the Assumption, ConneticutChurch leaders in Romania protest a proposal<strong>for</strong> Europe’s largest gold mine thatplans to bulldoze 8 churches and 9 cemeteries.<strong>The</strong> mining project at Rosia Montanain Transylvania’s Apuseni Mountains will<strong>for</strong>ce at least 2,000 people from their homesand require the removal of Roman remainsand relics from the region’s ancient Daciancivilization.Photo Courtesy Reefe Associatesplains each artistic element, from thechurch square to the altar, that has been assumedinto Christian churches throughouthistory.Final restoration will begin this summeron Santa Maria Antiqua, one of Rome’soldest and most prestigious churches. Setat the foot of the Palatine Hill, the church isnoteworthy <strong>for</strong> its varying types of Christianmural decoration spanning centuries.<strong>The</strong> earliest frescoes date from 536, includinga devotional image of the Virgin Maryand Christ Child, and carry through to theninth century, with a range of styles from afeather light brushtroke to that closely resemblingmosaic decoration. Visit www.archeorm.arti.beniculturali.it/sma/eng/index.html.John Paul II points to Pope St. Gregorythe Great as a guide <strong>for</strong> future generationsin praising his conviction that the historyof classical and Christian antiquity “constituteda precious foundation <strong>for</strong> all subsequentscientific and human development.”In a message sent to the president of thePontifical Committee <strong>for</strong> Historical Scienceson the 14th centenary of St. Gregory’sdeath, the pope remarked, “<strong>The</strong> futurecannot be built by disregarding the past.This is why on several occasions I have exhortedthe competent authorities to fullyappreciate the rich classical and Christianroots of European civilization, to transmitthe lymph to the new generations.”<strong>The</strong> Archdiocese of Boston prepares toshut down a significant number of its 357parishes. Though lay involvement hasbeen encouraged in this stage of the process,parishioners are worried followingthe announcement of parish closures byarchbishop Sean P. O’Malley that they willhave almost no chance of successful appealto higher authorities. Although the architecturaland historical significance of thePhoto: www.holytrinitygerman.orgHoly Trinity, Boston, is among theParishes chosen <strong>for</strong> closure.Giuliano Zanchi’s book Lo Spirito e lecose (<strong>The</strong> Spirit and Things) instructs thefaithful on the original meaning the Churchexpressed in divinely inspired <strong>for</strong>ms of artand architecture. Published by Vita e Pensiero,this work is a “guided tour of Christianchurches where physical things re-findtheir original <strong>for</strong>m and meaning throughunderstanding the ‘spirit’ in which theywere created.” From the first “domusecclesiae” to the Baroque, the author exchurchesis being considered, the archbishopsays it is only one factor; other importantconsiderations being the connection ofchurches to schools and the extent to whicha struggling immigrant group relies on aparish.Bernini’s “Charlemagne Wing” of theVatican reopened after a decade of restorationwith an exhibition of Baroque art. <strong>The</strong>exhibition entitled “Visions and Ecstasies:Masterpieces of European Art Between the17th and 18th Centuries” was presented<strong>for</strong> the 25th anniversary of the pontificateof John Paul II. <strong>The</strong> mystical experience,featured in this display of Baroque art, wasalso the focus of Karol Wojtyla’s doctoralthesis, which was dedicated to St. John ofthe Cross.Sanitago de CompostelaCalled the spiritual heart of Europe byJohn Paul II, the Cathedral of Santiago deCompostela expects to draw ten millionvisitors in 2004. This year is a holy year <strong>for</strong>the shrine millions of pilgrims have visitedsince the 9th century, when, according totradition, the bones of St. James the Apostlewere discovered and brought here. AfterRome and Jerusalem, Santiago de Compostelawas the third great pilgrimage site ofmedieval Christendom. <strong>The</strong> focus of thisyear’s jubilee is European unity, and theplanned events include a pilgrimage April21-24 by European bishops to commemoratethe entrance of ten new countries intothe European Union. For more in<strong>for</strong>mation,visit www.csj.org.uk.<strong>The</strong> Liturgical <strong>Institute</strong> at the Universityof Saint Mary of the Lake/MundeleinSeminary sponsored a conferenceentitled “Shape of the Liturgy—Shape ofthe Church,” October 22-24, 2003. Conferencespeakers addressed the new GeneralInstruction of the Roman Missal and itsimplications <strong>for</strong> architecture, hoping to usePhoto: <strong>The</strong> Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, 20008 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9

insights from the Church’s theology andTradition to expand upon and give contextto the GIRM’s directives.Michelangelo’s “Moses” is again on viewafter five years of restoration work onthe San Pietro in Vincoli Church whereit is housed. With the restoration of thechurch, which coincided with the 500th anniversaryof the election of Pope Julius II,<strong>for</strong> whom the architectural and sculpturalcomplex serves as a mausoleum, a walledinwindow was discovered that now allowsthe sun to shine directly on the statue. Fora virtual exhibition, see www.progettomose.it.Proposal by Alexandros Tombazis <strong>for</strong> anew Basilica at FatimaIn response to the increasing numberof pilgrims to Fatima, a new basilica designedby Alexandros Tombazis is beingbuilt. <strong>The</strong>re are commonly 10,000 whocome to attend Sunday mass at the currentbasilica, which seats 900 — the new basilicawill seat 9,000, making it among the largestCatholic churches in the world.Progress continues at St. James Chapelat Quigley Preparatory Seminary in Chicagoon restoration of the historic stainedglass windows. <strong>The</strong> fifth and final windowof the current restoration phase has beenremoved to Botti Studios in Evanston, Illinois.St. James Chapel, modeled after SainteChapelle in Paris, features a 28-ft. diameterRose Window in the rear of the Chapel,which has been completely restored. <strong>The</strong>Chapel is open daily <strong>for</strong> tours and the publicis invited to a concert held on the secondSaturday of each month in the Chapel.<strong>The</strong>re are plans <strong>for</strong> future renovation inwhich four more stained glass windowswill be renewed and restored.Unprecedented in its history, the governmentof Qatar has authorized the constructionof Christian churches. This followsthe establishment last November of officialdiplomatic relations between Qatar and theVatican. A neighbor of Saudi Arabia, thePhoto Courtesy meletitiki.grpopulation of Qatar is about 800,000, mostlyBedouin Arabs. Islam is the majorityreligion, though there are 45,000 Catholicimmigrants in Qatar, mostly from the Philippinesand India.As a customary part of beatification ceremonies,the pope continues to receivedozens of new relics each year. Despitethe Vatican placing greater restrictions onthe distribution of relics, their presentationis a tradition that won’t go away. WhileLatin-rite churches no longer require sliversof relics to be sealed in the altars, newrelics that are large enough to be identifiableas a body part are often placed intomb-like urns under the altars. This reflectsthe original practice of building altarsand churches over the tombs of martyrs.An exhibition at the Metropolitan Museumof Art in New York City showed thatEl Greco’s work still inspires Christiancontemplation. Visitors were remindedthat there is more to be admired in the late16th century master’s work than his techniques,but also the religious message infusedby this man of faith. Displaying 70works spanning his career, the show madepoignant links to the nature of art todayand the ongoing discussion about faithand culture. According to Jim Sullivan,through the work of artists like El Greco“they helped ‘make disciples of all nations’in the manner of St. Francis: without theneed of words.”<strong>The</strong> Notre Dame Center <strong>for</strong> Ethics andCulture is sponsoring a conference entitled“Epiphanies of Beauty: <strong>The</strong> Arts in a Post-Christian Culture.” <strong>The</strong> conference, to beheld Nov. 18-20, will examine the variety ofways in which the fine arts can help build amore genuinely Christian civilization in anera that is ever more deeply post-Christianin its character. Further in<strong>for</strong>mation aboutthe upcoming fall conference can be foundat http://ethicscenter.nd.edu.Bethlehem Priory of St. Joseph project<strong>for</strong> the Norbertine SistersTehachapi, Cali<strong>for</strong>niaN E W SA sculpture of Mary by artist JohnCollier that is part of the first memorialmonument to those who died at theWorld Trade Center. See <strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> 2003 <strong>Issue</strong> 8, p.5<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9 9Photo Courtesy Priory of St. JosephLettersEditor’s note: <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> is addingan additional feature to the journal. Beginningwith this issue, letters to the editor will be reviewed<strong>for</strong> publication and response. Pleasesubmit your letters to: Letters to the Editor, <strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Journal, P.O. Box 556, Notre-Dame, IN 46556 or email: dstroik@nd.eduBuilding to EndureTo further the discussion of the articleconcerning Built of Living Stones, I’m curiousto discover if the document acknowledgesnot simply the issues of the <strong>for</strong>ms ofarchitecture, but of their construction.Whether the <strong>for</strong>ms are traditional orotherwise, there exists a trend in buildingtoday to employ similar methods of constructionaimed largely at reducing cost.<strong>The</strong> un<strong>for</strong>tunate result of this has been tofoster the sense of the transitory over theenduring, and has stripped some of themore beautiful recently designed spacesof a necessary feeling of authenticity. Thatis to say, even where we find communitiesembracing a traditional language of architecturethe result, due to cheaper methodsof construction, gives more the effect of astage set than a sacred space. To initial appearanceswe read the <strong>for</strong>ms as beautifuland yet upon closer inspection we discoverthere is no real substance sustaining thepoetry.In a time when novelty and transitorinessare the norm, it is not enough <strong>for</strong> theChurch to seek only a surface architecture,but one that is lasting — a true and genuinewitness to our commitment to the buildingof the kingdom of God.John GriffinOklahomaPhoto Courtesy John Collier

A R T I C L E SA VACUUM IN THE SPIRITTHE DESIGN OF THE JUBILEE CHURCH IN ROMEBreda EnnisWhile on my way in the car to see thenew church built by Richard Meieron the outskirts of Rome, named “Godthe Merciful Father” (in the original Italian,“Dio Padre Misericordioso”), two phraseskept coming into my mind from Pope JohnPaul II’s Letter to Artists, in which he remarked:“even in situations where cultureand the Church are far apart, art remainsa kind of bridge to religious experience.”He goes on to mention whatthe Fathers said at the endof Vatican Council II: “Thisworld in which we liveneeds beauty in order notto sink into despair.” Evento people unfamiliar withRome, it will surely come asno surprise to learn that thecelebrated beauty of the centerof Rome bears no resemblancewhatever to the city’sdrab suburbs. As we drovealong the Via Prenestinaon the way to Tor Tre Teste— the site of the new Meierchurch — I noticed that thearchitecture along the waygot worse and worse. And,of course, when architectureis dull and drab, it tends tocreate a vacuum in the spirit.But was this vacuum nowabout to be filled?We turned the corner, leading to the inclinewhere the church is situated, and I gotmy first glimpse of the church. Almost atonce, however, I began to feel somewhatperplexed. <strong>The</strong>re in front of me I saw amass of snow-white concrete walls, bothcurved and straight, held together by glassand surrounded by a pale paved area anda low wall. I walked with two friends towardthe front of the church, but it wasnot clear, at first, just where we were supposedto enter the church. Looking throughthe glass façade, the eye comes to rest onthe wall which divides the nave from theatrium or narthex, and you think that thiscannot be the entrance because you do notimmediately see the inner door. <strong>The</strong> twoother entrances are between the curved“sails”: one leads to the Day Chapel andthe other to the Baptistry area.When finally we got into the atrium, Ifound myself in a rectangular space whichhad, apart from the small geometric holywater font, an inscription on the wall announcing,“This Structure Is a TestamentFront View of the Jubilee Church by Richard Meierto the Monumental Work of Men in theService of Spiritual Aspirations. RichardMeier, Architect.” I was surprised by this,not accustomed to seeing the name of thearchitect so prominently placed in theatrium of the church. To be honest, I ratherexpected that the inscription might be aquotation either from the Bible or from oneof the writings of Pope John Paul II, a textperhaps from his encyclical, “Dives in Misericordia”(published in 1988). <strong>The</strong> Popehimself had decided that the name of thechurch should be “God the Merciful Father.”It was a Sunday, and the parish priest,Don Gianfranco Corbino, was celebratingMass as we entered. We remained quietlyat the back of the church, a good place toobserve both the people and the building.My first impression of the nave was that itwas really rather small. From earlier publicityand publications, I was expecting tofind myself in a vast space with seating <strong>for</strong>about 700 people. Don Corbino confirmedthat it holds, in fact, about 300 people only,or 350 if extra chairs are added. <strong>The</strong> literatureon the church states that it holds 500.<strong>The</strong> parish itself is a mere seven years old.(<strong>The</strong> people in the parish had originally belongedto a parish nearby.) It has a populationof about 8,000 people (many youngpeople and about 2,500 family units).Be<strong>for</strong>e the building of the new church,the parishioners worshipped in a plain,secular space. Needless to say they are delightedto have a church and also happythat their church has provoked so muchinterest internationally. Many of the visitorsare students of architecture with theirprofessors. However, the publicity aboutthis project, upon its completion, has beennoticeably limited in Italy — surprisinglyso, given the fact that it is a Jubilee Church.When it was consecrated last October, minimumcoverage was given by Italian TV andPhoto: Breda Ennisnewspapers. Perhapsthe fact that no Italianarchitect was invitedto present a project canaccount <strong>for</strong> the tepidreaction.But there could beanother reason as well.In 1993, as part of aproject to build 50 newchurches <strong>for</strong> the year2000, a competitionwas launched (opento all countries whichare part of the DirettivaArchitettura dellaCommunità EconomicaEuropea) <strong>for</strong> churchand parish buildingdesigns. A specific requestwas made <strong>for</strong>projects which includeda church, a building<strong>for</strong> parish activities,and accommodation <strong>for</strong> clergy. A fewlocations were indicated, among them thearea of Tor Tre Teste. <strong>The</strong>re was a massiveresponse — about 534 projects were presented.No project was thought suitable <strong>for</strong>this particular area, however. <strong>The</strong> competitionran into difficulties, in part because ofthe high number of participants and alsobecause of the excessive number of jurymembers (coming from too many and toovaried backgrounds). Criteria were alsodifficult to establish, and agreement waseven more so.Lessons were learnt after this unhappyepisode, and when it was suggested that achurch be built to celebrate the Jubilee ofthe Year 2000, a much smaller commissionwas established. Only six internationalarchitects were invited to present projects,and clear criteria were indicated. It was decided,<strong>for</strong> example, that the architect chosen<strong>for</strong> the project would not have to bea Christian believer. And, in the end, thename selected was that of Richard Meier,an architect from New York.10 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9

View of rear elevationMass was being celebrated during myfirst visit, and it soon became clear thatthere are some serious problems with theacoustics. <strong>The</strong> priest’s voice was muffled,and bounced off the walls. You heard himand his echo. <strong>The</strong> same happened whenthe organist began to play and with thecongregational responses. Some technicaladjustments have since been made, butit is hard to see how this problem can becompletely resolved. <strong>The</strong> organ itself is apowerful one.Don Corbino has a very united and activeparish. <strong>The</strong>y have published a bookof cartoons <strong>for</strong> children, entitled “Tracce diun cammino” (Traces of a Journey), wherethe history of the parish is narrated rightup to the day the church was consecrated.Numerous gifts were received from otherparishes and various associations, e.g.,chalices, liturgical vestments, etc. A giftof Pope John Paul II was the awardingof “titular” status to this Jubilee Church,and Cardinal Crescenzo Sepe, prefect ofthe Congregation <strong>for</strong> Evangelization, wasgiven the titular title.When the Mass ended we began to“feel” our way through the church. Onething I love about Roman churches is that,moving from the nave to the sanctuaryarea, you begin to experience a distinct“change of space.” But this did not happen.<strong>The</strong> altar itself is a block of travertineresembling a boat. It has the relics oftwelve saints, including St. Lawrence, St.Sebastian, and St. Maria Goretti. <strong>The</strong> long“bench” to the right of the altar I foundquite banal (it reminded me of the benchesin train stations). And the box-like ambodid not impress me either. Of course, ifyou have lived <strong>for</strong> many years in Rome,and been privileged to enjoy the deluge ofcolor within the ancient city, it can be difficultto accustom yourself to stark interiorsand raw geometry.On the positive side, the name of LeCorbusier comes to mind when you considercertain elements in the church, theprofound conical window behind the cross,the clear glass slit running around thechurch etc. But, walking to the end of thenave, and looking back directly at the altar,you suddenly realize that the beautifulCross — from the 1600’s, a wooden crossand Christ figure made of “papier mache,”a gift from a nearby parish — is not in linewith the altar. I found this really disconcertingespecially since the altar is supposedto be the sacramental focal point of thechurch. It is the symbolic “source of light,”from which “rays” stretch out in every direction.But, when the altar and the crucifixare not on the same axis, a visual “tension”is created which is in no way conducive toprayer or contemplation. In relation to thechoice of a crucifix <strong>for</strong> the altar wall, I wascurious about the fact that no contemporaryartist had been approached to designone. An interior like this would have benefitedfrom a crucifix like the one made byGiuliano Vangi <strong>for</strong> the Cathedral of Paduain 1997. Vangi’s Christ is made of silver,nickel, gold, and bronze.During my second visit to the church Ihad a long chat with Don Corbino aboutthe day-to-day life of his church. He toldme that thousands of people have cometo see it. When I asked him about the costof running a church of this complexity, headmitted that the income from the parishcould not cover the expenses. I saw thathe had a severe cold. He told me that thechurch heating system is under the travertinefloor and this means that, apart frombeing inadequate, it is necessary to turn iton at least ten hours be<strong>for</strong>e any ceremonyPhoto: Breda EnnisA R T I C L E Sor Mass. This is, of course, apart from thecost of regularly cleaning the vast quantityof glazed windows (<strong>for</strong> the church and theparish centre). Rome is famous <strong>for</strong> sciroccowinds from the desert — they tend to leavea thin layer of sand on every surface theyfind, and they are very frequent. So howare they going to keep the glass clean andthe costs down? This is a heavy burden, obviously,<strong>for</strong> the new church and parish ofGod the Merciful Father — more a misery,I would say, than a mercy!As one moves towards the sacristy,through an opening to the left of the altar,there is a large display case. Inside is a collectionof chalices, a crucifix, candlesticksetc., designed by the Jewellers Bulgari anddonated to the church. An extraordinarilybeautiful gift. <strong>The</strong> chalices are an excellentmix of Renaissance, Baroque and Gothicinfluences. Not surprisingly they attractedthe attention of many of the visitors. <strong>The</strong>collection itself is situated immediately behindthe altar wall on which the great crucifixis hanging. I wondered, though, why itwas put in that position. It would, I think,have been a better idea to have kept thecollection somewhere in the sacristy. Peoplelooking in from the back of the churchcan see the sacred objects, as it were, “onshow.”<strong>The</strong> Day Chapel and the Baptistry areaare separated from the main nave by an L-shaped wall. <strong>The</strong>se are directly under themassive curved north wall or “sail” andseem to be a little lost in all the pale travertineand white cement. <strong>The</strong> chapel canseat about 24 people. At the end of the cha-Main entrance door into the churchPhoto: Breda Ennis<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9 11

A R T I C L E SView of interior toward altarpel there are the confessionals. I sat downand looked towards the altar. What caughtmy eye was the tabernacle. It is a goldensquare with a circular design on the front.Apparently Meier wanted a higher andnarrower one. <strong>The</strong> tabernacle is very beautiful.<strong>The</strong> front has a circular roughenedsurface which is pleasant to observe. It isat an angle so that it can be seen from boththe main nave and the chapel.I noticed that the parish has placed astatue of the Madonna in the chapel witha candle holder in front of it. Don Corbinotold me that a new statue will be madelater. Meier’s iconoclastic tendencies, itwould appear, did not seem to encouragehim to anticipate the specific devotionalneeds of the parish and parishioners,which is a pity! Some images in color, asan aid to prayer and contemplation, would,perhaps, have been the best idea. Visitingthe church one’s mind kept looking backto Le Corbusier’s use of stained glass inhis chapel at Ronchamp (1950–54). I foundmyself reflecting on some expressions usedby Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in his bookentitled Spirit of the Liturgy (1999, IgnatiusPress) where in a chapter entitled “A Questionof Images,” he speaks about iconoclastictendencies in <strong>Sacred</strong> Art. He notes:“Images of beauty, in which the mystery ofthe invisible God becomes visible, are anessential part of Christian worship.”Photo: Breda Ennis<strong>The</strong> confessionals are smallcubicles with two seats in eachone and the doors are made ofwood and glass slits, linking upto the design in paneled woodon the vertical south wall of themain nave. This creates a senseof continuity between the two areasof worship. <strong>The</strong> priest andthe parishioner can be clearlyseen inside. I understand thatan old-style grating confessionalwill be added to cater <strong>for</strong> thepastoral needs of those peoplewho do not like the ‘face to face’confessional style. FigurativeStations of the Cross are beingmade, in bronze or stone. <strong>The</strong>original idea, I understand, wasto have each Station representedby a Greek cross.One of the areas in the churchI find most problematic is thebaptismal font and where it hasbeen placed. It is just to the leftof the nave, in full view of thecongregation and the celebrant atthe altar. Again it is a rectangulardesign in travertine, with an indentedcentre <strong>for</strong> the holy water,and in front of it there is a smallsloped area. You almost fallover it as you move to the side ofthe nave. I felt that it is too closeto the main altar and that it getslost in the hub of geometricalconstructions nearby, i.e., the confessionals,the organ, the day chapel wall, etc. Iwould have liked to have seen it placednear the entrance door of the “corridor”which leads to the day chapel. <strong>The</strong> baptismalfont is the place where Christians areinitiated into the communion of believers.Only after this initiation are they invitedto take their place around the main altar.Here, un<strong>for</strong>tunately, the font and altar areso near together that it is difficult visuallyto perceive that they represent two distinctstages in the Christian mystery.Much has been said and written aboutthe three curved walls, or sails. One’s mindgoes back immediately to John Utzon’sSydney Opera House (1957–73), thoughthe latter is a more exuberant and dynamicstructure. <strong>The</strong> feeling I get from the threecurved walls is of a building falling in uponitself — even if the parish building and belltower “lean against” a strong vertical wallwhich marks the demarcation line betweenthe church and the rest of the complex. <strong>The</strong>whole structure is visually very analyticaland “cubist.” When I look at old or newchurches I always search <strong>for</strong> that sense ofa breakthrough of the sacred into humanexperience (on a visual level) — what theRumanian scholar Mircea Eliade called “hierophany.”He says that in developed religioussystems there are three cosmic levels— heaven, earth, and the underworld,linked together by the vertical “axis mundi.”Church spires, domes and bell towershave this quality, and this is why they areable to soar up above all their surroundings.<strong>The</strong> Meier church seems to lack thisdynamic element. Again I returned, in mymind, to the Le Corbusier church in Ronchamp.In comparison, the Meier church isvery rational in its conception, whereas theLe Corbusier church draws you up into itsmystical web.<strong>The</strong> bells in the tower were cast at thePontifical Marinelli Foundry and are dedicatedas follows: the first and biggest bellto Europe and the Virgin Mary — it containsa list of all normal Jubilees from 1300.<strong>The</strong> second is dedicated to America andSts. Peter and Paul, Patron Saints of Rome.<strong>The</strong> third is dedicated to Africa and St.Charles Borromeo (to honor Pope JohnPaul II, whose first name is Karlo). <strong>The</strong>fourth represents Oceania, and is dedicatedto St. Cyril of Alexandria and St. ThomasAquinas — the name of the parish whichowned the property on which the newchurch stands. <strong>The</strong> fifth and last is dedicatedto Asia and Sts. Francisco Saverio andThérèse of Lisieux. Four of the bells list,respectively, the dates of the first baptism,funeral, and wedding in the church, andthe date of the laying of the first stone.When the Vicariato commissionedMeier to construct this church they appointedan Italian engineer, Ignazio BrecciaFratadocchi, to supervise the work.Some modifications were made to Meier’soriginal project. <strong>The</strong>se relate to the parishcenter only, where some new spaces werecreated (relating to the actual needs of theparish). <strong>The</strong> church authorities made someView of Interior toward entrancePhoto: Breda Ennis12 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9

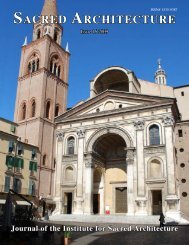

A R T I C L E SCHARLES BORROMEO AND CATHOLIC TRADITIONREGARDING THE DESIGN OF CATHOLIC CHURCHESMatthew E. Gallegos, Ph.D.While the Tridentine documents containedfew specific directives regarding thedesign of Catholic churches in the context ofthe Protestant Re<strong>for</strong>mation, the Council affirmedthe authority of tradition in all mattersrelated to Christianity. It was in thatcontext that one of the main participantsin the Council wrote a summation of theChurch’s tradition regarding the design ofCatholic churches. In light of the two mostrecent documents regarding the design ofCatholic churches in the United States, Environmentand Art in Catholic Worship (1978)and Built of Living Stones: Art,<strong>Architecture</strong>, and Worship (2000),it is useful to revisit the understandingof Church traditionthat existed prior to their publication.1Charles Borromeo (1538–1584), whom the CatholicChurch recognizes as a saint,published a summary of Catholictraditions regarding churchdesign fourteen years after theconclusion of the Council ofTrent. Borromeo’s publication,Instructiones Fabricae et SupellectilisEcclesiasticae, was the centraldocument that applied thedecrees of the Council of Trentto the design and furnishing ofCatholic churches. 2 Borromeoofficially wrote the Instructionesto direct construction within theArchdiocese of Milan, but hisintention was that it have widerusage. Borromeo publishedthe document in 1577, and it was reprintedwithout major revisions at least nineteentimes between 1577 and 1952. Until thelate 1960s the architecture and furnishingsof most Catholic churches throughout theworld were consistent with the Instructiones’directives.Borromeo began his treatise with aletter in which he identified that he wascompiling the directives from in<strong>for</strong>mationprovided by two sources of authority,one ecclesiastic and the other secular. Hewrote:... this only has been our principle,that we have shown that the norm and<strong>for</strong>m of building, ornamentation andecclesiastical furnishing are preciseand in agreement with the thinking ofthe Fathers ... and ...we believe it necessaryto take the advice of competentarchitects. 3As an active and influential participantin the Council of Trent, Borromeo had intimateknowledge of the Church’s official decreesand of their intent. 4 He served as thePapal Secretary of State under Pope Pius IVduring the Council’s final sessions. He alsowas one of the most influential agents of re<strong>for</strong>mafter the Council’s conclusion, servingfirst as the Papal Legate to Italy and then asthe Archbishop of Milan. Along with authoringInstructiones, he exerted great influencein the writing of the Church’s revisedceremonial manual, Pontificales secundumFacade of Milan Cathedralritum et usum Sancte Romane Ecclesie (1561);the decree regarding priest’s seminarytraining, Cum adolescentium aetas (1563); therevised Roman Breviary (1568); and the revisedRoman Missal (1570).Borromeo’s Instructiones incorporatedhis awareness of Catholic church architecturein Italy as well as of Church teachingand of recent and historic Church and seculardocuments. <strong>The</strong>re is evidence that Borromeoowned a copy of and incorporatedideas from a sixteenth-century edition ofthe medieval text by William Durandus, RationaleDivinorum Officiorum (c. 1280), whichdeals with the symbolism of churches andchurch ornament. 5 Evidence of Borromeo’sreliance on Durandus’ text in the Instructiones,is his consistent use of numbers thatcorrespond to Catholic doctrinal teachingsas Durandus recommended. <strong>The</strong>se includeuse of the numbers three, five, seven, andtwelve in recognition of respectively theTrinity, Pentecost, the Seven Sacraments,and the Twelve Apostles.Borromeo’s Instructiones also incorporateideas that were contained in seculararchitectural treatises to which he had access.6 <strong>The</strong>se included the ancient Romantreatise by Vitruvius, De Architectura (c. 49BC - 14 AD); Pietro Cateneo’s L’Architetturadi Pietro Cateneo Senese (1554); and AndreaPalladio’s I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura(1570). <strong>The</strong>se secular sources as well asChurch tradition advocated using platonic<strong>for</strong>ms such as circles, domesand vaults as evocations ofperfection and of the heavenlyrealm. Both Church and Westernaesthetic tradition favoredthe use of an odd rather thanof an even number of units soPhoto © Mary Ann Sullivanthat a composition would alwayshave a clear center. Thispredilection <strong>for</strong> centrality andanthropomorphism often resultedin symmetric compositions.If circumstances dictatedasymmetry, the right side wasfavored due to the negativeassociations within Westerncivilization of all things relatedto the left, including the Latinword <strong>for</strong> left, sinestra.From this wide range ofecclesiastical and secular sourcesBorromeo compiled neithera theoretical nor a theologicalwork, but a compilation of theChurch’s traditional design elementsand organizational strategies <strong>for</strong>Catholic churches. It was Borromeo’s goalto identify design elements that con<strong>for</strong>medto official Church teaching and not to advocatea particular aesthetic style. Whilethis is true, Borromeo wrote the Instructionesin the context of the explosion of artisticcreativity which typified the baroque aesthetic.<strong>The</strong> Counter Re<strong>for</strong>mation and thebaroque aesthetic were symbiotic. Whilethe Catholic Church was emphasizing thatthe sacred could be encountered throughthe senses and most Protestant re<strong>for</strong>merswere rejecting this idea, architects, sculptors,and artists such as Giovanni LorenzoBernini, who were working <strong>for</strong> Catholicclients, were developing the baroque aesthetic.<strong>The</strong>se designers worked with theintention of integrating all the visual arts tomaximize the engagement of people’s sensibilities.Despite the boisterous aesthetic14 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9

context in which Borromeo was writing,he only occasionally refers to the classicalorders or other stylistic issues within theInstructiones.Borromeo organized the text of theInstructiones into thirty-three chapters.Thirty chapters focus on the design oftypical parish churches, and also includein<strong>for</strong>mation regarding cathedrals. <strong>The</strong>last three chapters address the designof churches <strong>for</strong> oratories, convents, andmonasteries. Despite the chapters’ titles,the topics covered are not always clearlysegregated within the chapter divisions.<strong>The</strong> first thirty chapters address six categoriesof in<strong>for</strong>mation: a church’s siting,plan configuration, exterior design, interiororganization, furnishings, and decoration.With regard to a church’s siting, Borromeostates that a church should be in aprominent location. 7 If natural topographydoes not provide an advantageoussite to give a church visual prominence aswell as to guard against floods and dampness,the church should be placed on araised plat<strong>for</strong>m. Borromeo recommendsthat three or five steps provide access tothe plat<strong>for</strong>m. If circumstances requirethat there be a greater number of steps,there should be a landing at either everythird or fifth step. Churches are to be freestanding,having no structures directly attachedto them other than a sacristy. <strong>The</strong>residence of the pastor or bishop may beclose by or connected to the church by apassage, but the church and clerics’ residenceshould not share a common wall.Churches should be situated in non-commercialareas, far from stables, markets,noise, unpleasant smells, or taverns. Ifpossible, a church’s sanctuary should betoward the east and should align with thesunrise at the time of the equinox.Borromeo’s concerns regarding thesiting of churches are consistent with thosecontained within the architectural sourceswith which Borromeo was familiar. Palladio,one of those sources, states thatchurches should sit on prominent siteswithin a city or on public streets or nextto a river so that people passing through atown may see them and:may make their salutations and reverencesbe<strong>for</strong>e the front of the temple[church]. 8Catholics frequently observed thiscustom by making the sign of the cross,whenever they walked or drove past achurch, and men customarily tipped theirhats. Borromeo’s siting directives are alsoconsistent with the hierarchy of buildingtypes as they were understood in Westerncivilization from the Renaissance era untilthe nineteenth century. 9 Renaissance architecturaltheorists recognized that thereare five building types to which all buildingscon<strong>for</strong>m and among which a hierarchyof status exists. Places of veneration,such as a domus dei, hold the most exaltedplace within that hierarchy and as such requireprominent siting, the expenditure ofsuperior craftsmanship and materials, andshould be freestanding. Buildings of lesserimportance such as private residences, commercialstructures, or markets merit lessprestigious sites, and more modest expendituresof material, labor, and financial resources.Borromeo clearly states that the Latincross or cruci<strong>for</strong>m plan is the preferred configuration<strong>for</strong> Catholic churches. 10 He doesrecognize that central plan configurationsS. Maria Vallicelli, Rome, 1605also have historical precedent, and siting,economic concerns, or other circumstancesmay require variations from the Latin crossprototype. Not distinguishing between theterms “nave” and “aisle,” Borromeo statesthat a church may have one, three, or five“naves,” meaning that the church may be ahall church, or have either single or doubleaisles on either side of its nave. A church’smain entrance and nave should align axiallywith the church’s main sanctuary. <strong>The</strong>sanctuary, if possible, should be containedwithin a vaulted apse <strong>for</strong>m.Borromeo indicates that there should bea distinct architectural element that <strong>for</strong>msthe entrance into a church. Dependent onsite and budget restraints, an atrium, portico,or vestibule, or a combination of theseelements can fulfill this requirement. Thiscomponent of a church’s facade regardlessof its <strong>for</strong>m should have a distinguishabledepth and serve as a visible transition spaceinto the church. At various times in history,this transition space accommodated ritualinitiation into the church or ritual cleansing.Borromeo appears to reject this transitionalspace’s cleansing associations. He stipulatesthat the holy water vase that contains theblessed water with which members of thecongregation cross themselves upon enteringa church, be located not in the transitionalspace, but inside the church itself.A R T I C L E SBorromeo suggests that a churchshould be large enough to accommodatenot only the area’s local inhabitants, butalso the large numbers who would congregatefrom distant places <strong>for</strong> holy days.He identifies that a church’s interior areashould provide approximately four squarefeet of space <strong>for</strong> each person who will attendthe church regularly.Seven different chapters in the Instructionesaddress aspects of the exterior appearanceof a Catholic church. Borromeoidentifies that the church’s entrance facadeis its most important exterior wall and thatit should contain all of a church’s exteriorornamentation and decoration. Narrativevisual embellishments normally shouldnot be placed on a church’s side or rear elevations.In reference to the nature of thefront facade’s narrative decoration Borromeowrites:... there is one feature above all thatshould be observed in the facade ofevery church, especially a parochialchurch. In the upper part of the chiefdoorway on the outside, there shouldbe ... the image of the most BlessedVirgin Mary, holding her son Jesus inher arms; on the right-hand side thereshould be the effigy of the saint towhom the church is dedicated, whileon the left-hand side ... the effigy of anothersaint to whom the people of thatparish are particularly devoted.Borromeo recognizes that if circumstancesdo not allow having three separateimages or statues on a church’s frontfacade, then at least the image of the saintto whom the church is dedicated should berepresented.Borromeo’s directives regarding achurch’s exterior doors and windows hadboth practical and symbolic purposes. Hestates that a church’s front facade shouldhave an odd number of doors, and if possiblereflect the church’s number of “naves”[nave and aisles]. If a church’s central naveis sufficiently wide, three doors shouldenter directly into the nave in addition tosingle doors that lead into the nave’s adjacentaisles. Borromeo observed that ifa church does not have side aisles, it stillshould have three doors in its front facade.A church there<strong>for</strong>e should have a total ofthree, five or seven doors in its front facade.<strong>The</strong> central doorway should be thelargest and have greater ornamentation,especially if the church is a cathedral, as itaccommodates the clergy and their retinuein ceremonial processions. Borromeo’s directivesregarding the location of windowsare equally specific. His concerns relate toissues of illumination, security, and maintaininga proper decorum within a church.He writes:the windows should be constructedas high as possible, and in such a waythat a person standing outside cannotlook inside.<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9 15

A R T I C L E SIf possible a church’s principle sourceof interior illumination should be providedby clerestory windows into the church’snave and windows that are placed highon the walls of the church’s side aisles. Allwindows should have provisions to guardagainst unauthorized entry and should beodd in number. If the church has a naveand aisle configuration, the window spacingshould align with the center of thespaces that are defined by the columns inthe nave arcade or colonnade. If the naverequires additional illumination, a window,preferably round, should be placedabove the doorways in the church’s frontfacade or in the walls of its apse. Borromeoobserves that lanterns that project above achurch’s roof line and oculi in domes canilluminate either a church’s sanctuary ornave from above, but cautions that suchdevices are difficult to make watertight.Borromeo is adamant about not placingaltars directly under or close to a potentialsource of water leakage. He also discouragesplacement of windows in any locationwhere the illumination provided by themwould prevent the congregation from havinga clear view of either the main altar orside altars.Borromeo’s directives regarding windowsclosely follow those of the Renaissancearchitectural theoretician and Catholicpriest Leon Battista Alberti. Albertistated that:nothing but the sky may be seenthrough them [the windows], to theintent that both the priests that are employedin the per<strong>for</strong>mance of DivineOffices, and those that assist on accountof devotion, may not have theirminds in any way diverted. 11Church tradition as expressed by Durandusheld that:... by the windows, the senses are signified:which ought to be shut to thevanities of this world, and open to receivewith all freedom spiritual gifts. 12Bells and bell towers are the last exteriorfeatures of a church that Borromeoaddresses. 13 He states that the purposeof church bells is to call people to liturgywithin the church, to mark the hours atIl Gesu, Giacomo da Vignola, 1568-1575, in Rome, Italywhich the Divine Office is to be prayed,to mark the times of the Angelus, and totoll the death of one of the faithful. He instructsthat bells should be either in a freestandingtower, or in towers that <strong>for</strong>m apart of the church’s front facade. If there isonly one tower, it should be on the churchfacade’s right side as a person approachesthe church. If circumstances do not permitthe construction of a bell tower, the bellmay hang within a pier or buttress in thesame location as that of a single tower. Acathedral should have seven bells in itstower, but a minimum of five is allowable.Even the humblest church should have abell that can be played in two distinct manners.14 Although the tower is to be of solidconstruction, the actual belfry should beopen on all sides to allow the sound of thebell to radiate in all directions.Towers should have a fixed cross attheir apex. A clock and a weather vanemay be incorporated into a bell tower’sdesign. <strong>The</strong> clock’s face should show theday’s third, sixth, ninth, and twelfth hoursto mark the times of the Divine Office. <strong>The</strong>vane should have two components. <strong>The</strong>tower’s fixed cross may serve as the vane’sfixed shaft. <strong>The</strong> vane’s variable componentshould be the figure of a cock. <strong>The</strong> fixedcross represents the solidity of faith, whilethe moveable vane’s cock <strong>for</strong>m representsboth perpetual vigilance and the variabilityof all things other than faith. 15A church’s interior organization, furnishings,and decoration are the focus of amajor portion of Borromeo’s Instructiones.Borromeo identifies that a church’s mainaltar and sanctuary should be the nave’saxial focus and each transept arm can accommodatea side altar. If a church doesnot have a transept and/or if the side aislesare of sufficient width, side altars shouldbe the axial focus of a church’s side aisles. 16In discussing a church sanctuary’s design,Borromeo states that a sanctuary’s floorlevel should be an odd number of stepsabove that of the nave and side aisles. Ifcircumstances permit, the sanctuary’s floorfinish should be of a more durable, refined,and carefully crafted material than that ofthe nave and aisles. <strong>The</strong> sanctuary’s vaultshould contain mosaicor other decorativework. A railing atwhich the congregationPhoto: Varrian, Italian Baroque and Rococo <strong>Architecture</strong>receives communionshould separate thenave from the sanctuary.<strong>The</strong> sanctuary’ssize should be adequateto accommodate thosesolemn occasions thatinvolve a large numberof clergy.<strong>The</strong> main altar holdingthe Blessed Sacramenttabernacle shouldbe the principle objectCiborium and tabernacle, designed byPellegrino Tibaldi, 1581, <strong>for</strong> the MilanCathedralof focus in the sanctuary while also accommodatingthe saying of Mass. It shouldrest at least one step, if not three stepsabove the height of the sanctuary’s floorlevel. Side altars should support devotionalstatues and contain reliquaries. Side altarsmay directly adjoin a wall but the mainaltar must be freestanding. <strong>The</strong> main altarshould be made of solid stone or faced withmarble and must contain relics of at leasttwo saints. If the main altar is not made ofsolid stone, an altar stone containing relics,which is also identified as a portable altar,should be within the altar’s top surface.Borromeo conveys that a decree issuedby his regional provincial council ofbishops stipulated that the Blessed Sacramenttabernacle should rest on the mainaltar. 17 This requirement became a part ofthe Church’s rubrics in 1614. <strong>The</strong> Ceremonial<strong>for</strong> Bishops, which was in effect in Borromeo’sepiscopal province when he wrotethe Instructiones, stipulated that in contrastto the requirement <strong>for</strong> parish churches, theBlessed Sacrament tabernacle in a cathedralwas not to be located on its main altar.A cathedral’s tabernacle was to rest onan altar within a separate chapel that wasdedicated to that purpose and which wasadjacent to the sanctuary. Voelker observesthat the Apostolic Constitutions, a fourthcenturytreatise on religious discipline thatwas a part of the tradition Borromeo drewPhoto: Da Passano, Storia della Veneranda Fabbrica, 199816 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9

A R T I C L E SEngraving of Milan Duomo, 1809, showing crucifix on rood beam, twoambos, and a canopy above the tabernacle.upon, identified that within the sanctuaryof a cathedral:...in the middle, let the bishop’s thronebe placed, and on each side of him letthe presbyters sit down. 18Such an arrangement required that thealtar be located between the body of thenave and the bishop’s cathedra. Borromeostates that the prohibition against placingthe tabernacle on the altar in cathedralchurches was motivated by the desire tomaintain an unimpeded visual sightlinebetween the cathedra and the congregation.Borromeo’s resolution of this requirementwithin his archdiocese was to raisethe tabernacle on columns above the altar,maintaining a line of vision between thecongregation and the cathedra. In circumstanceswhere the cathedra, the altar andthe tabernacle are all in axial alignmentwith the nave, a freestanding or suspendedcanopy, a baldachin, should be placed overthe altar and tabernacle.Borromeo envisioned that most churchservices would occur during daylight hourswhen a church’s interior would receive naturallight. Despite this circumstance, Borromeostipulates that certain candles or oillamps must burn inside a church’s sanctuary,regardless of the natural illuminationlevels within the building. 19 This requirementwas prompted by Catholics’ identificationof a burning flame as a symbol ofChrist’s presence, because of Christ’s selfidentificationas “the Light of the World.” 20<strong>The</strong> required artificial light sourceswithin a church’s sanctuary include a lampadarium,which is a lantern whose flameis referred to as the sanctuary light. 21 <strong>The</strong>lampadarium contains either oil lamps orcandles and should be located in visualproximity to the Blessed Sacrament tabernacle.<strong>The</strong> sanctuary light is to burn wheneverthe Blessed Sacrament is in the tabernacle.<strong>The</strong> lampadarium should have threeor five lamps; seven in large churches; or aminimum of one in smaller churches. Inaddition to having the lampadarium closeto the tabernacle, six candlesticks should beon the main altar. 22 Only two of the altarcandles are to burn during most liturgies,but four or six should burn during Solemnor High Mass and other special observances.In addition to the six candlesticks, Borromeoidentifies that a crucifix should be onor above the main altar. 23 Should a churchhave a diaphragm arch above its sanctuary,the crucifix should be on the diaphragmwall above the arch.Borromeo does not establish definitiveplacement <strong>for</strong> a church’s ambo, whichaccommodates the proclamation of scripture,or <strong>for</strong> a pulpit, which accommodatespreaching. He states that these furnishingsshould be convenient to the altar, not blockthe congregation’s view of the altar, and besituated so the congregation can easily seeand hear the ambo’s or pulpit’s occupants.Borromeo states that ideally there shouldbe two ambones, one accommodating thereading of the Gospel, the other the epistle.From the congregation’s viewpoint, theGospel ambo should be on the nave’s leftside and the epistle on its right. A singleambo can fulfill both functions if circumstancesdictate that there only be a singleambo. In those circumstances it should beon the Gospel side.Sacristies should be adjacent to the sanctuary.Ideally, a church should have twosacristies. One would be next to the mainsanctuary and the other would be locatedPhoto: Da Passano, Storia della Veneranda Fabbrica, 1998close to the church’s entry doorway andprovide storage <strong>for</strong> vestments and a placewhere the ministers could vest. <strong>The</strong> vestingsacristy’s location by the church’s entrydoorway allowed the priest who was sayingMass to initiate and close liturgies witha <strong>for</strong>mal procession, an ancient Churchtradition. At the bishop’s discretion, moremodest churches could function with onlyone sacristy if it was located close to thesanctuary.Four chapters of Borromeo’s Instructionespresent directives regarding additionalfurnishings <strong>for</strong> a church. Two chaptersdeal with sacrariums, i.e, special sinks <strong>for</strong>washing altar linens and other items associatedwith the Mass; and furnishings toen<strong>for</strong>ce the segregation of the congregationby gender. A lengthy chapter contains adiscussion of baptisteries. Detailed specificationsare provided <strong>for</strong> baptisteries thatcould accommodate baptism by immersionor affusion, placing either the requiredpool or pedestal type baptistery withina stepped depression so as to signify descentinto a sepulcher. A cathedral’s baptisteryshould be freestanding, while thoseof most churches ideally would be locatedwithin either a chapel or in front of an altarat the rear of the church on the Gospel side,although it could be located on the epistleside. <strong>The</strong> directives regarding confessionalsfocus on providing privacy <strong>for</strong> thepenitent while simultaneously removingany appearance or avenue <strong>for</strong> inappropriateconduct or pecuniary gain on the partof the confessor. Detailed dimension andmaterial requirements are recommended<strong>for</strong> baptisteries and confessionals.Two chapters and portions of othersin the Instructiones identify directives regardingthe use of decoration, religious images,relics, and graphic inscriptions withinchurches. In 1563, the Twenty-Fifth Sessionof the Council of Trent had issued a statement“On the Invocation, Veneration, andRelics of Saints, and on <strong>Sacred</strong> Images.” 24Within this statement the Council reiteratedthe Second Council of Nicaea’s positionregarding these issues, i.e., that Christiandogma makes images, especially images ofChrist, imperative, as in them, “the incarnationof the Word of God is shown <strong>for</strong>thas real and not merely phantastic.” NicaeaII extended this justification of religiousimagery beyond pictorial representationsof Christ, by stating:with all certitude and accuracy thatjust as the figure of the precious andlife giving Cross, so also the venerableand holy images, as well as in paintingand mosaics as of other fit materials,should be set <strong>for</strong>th in the holy churchesof God, ... the figure of Our Lord Godand Savior Jesus Christ, of our spotlessLady, the Mother of God, of the HonorableAngels, of all the saints and ofall pious people. 25<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> 2004 <strong>Issue</strong> 9 17