Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

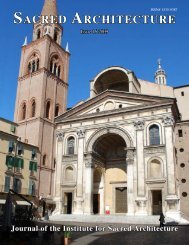

<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong><strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010ISSN# 1535-9387Journal of the <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>

D E U S F U N D AV I T C I V I T A T E M I N A E T E R N U M“Dear friends, today’s feast celebrates a mystery that is always relevant: God’s desire to build a spiritual temple in the world, a communitythat worships him in spirit and truth. But this observance also reminds us of the importance of the material buildings in whichthe community gathers to celebrate the praises of God. Every community there<strong>for</strong>e has the duty to take special care of its own sacredbuildings, which are a precious religious and historical patrimony. For this we call upon the intercession of Mary Most Holy, that shehelp us to become, like her, the ‘house of God,’ living temple of his love.”—Pope Benedict XVI on the Feast of the Dedication of the Lateran Basilica, 9 November 2008.It is well known that the conventionalwisdom on building churchesis in disrepute. Even the unwashedmasses are revolting against the dictatesand iconoclasm of the past fiftyyears. Yet, there is still some bathwaterthat needs to be emptied. Not onlydid the modernist project break withtwo thousand years of sacred architecture,it also rejected the traditionalcity amongst which the temple stooda witness. <strong>The</strong> resulting churches turntheir back on the street or sit like adoctor’s office in the middle of a seaof asphalt. One of the most insidiousstrictures of the conventional wisdommandates that any new churchneeds twenty acres. This twenty acrerule reminds me of the sixty-five footrule that necessitates building theatrechurches according to some liturgists.Where to find twenty acres at an economicalprice? Why, the cornfield, ofcourse. <strong>The</strong> reasons given <strong>for</strong> the necessityof a large tract of land are playingfields, convenient parking, and futuregrowth. Yet these factors should not beseen as the primary goals in building ahouse of God, but should be balancedwith the rich history of churches builtin the midst of our towns and cities.To put the twenty acre rule into context,consider that a traditional parishchurch in a small town with 800 seats,a grade-school, a playground, a rectory,and on and off street parking typicallytakes up three to six acres. Surprisingly,one of the most well knownand largest of American cathedrals,Saint Patrick’s, sits on a block in Manhattanof only two acres. <strong>The</strong> reality isthat twenty acres is the equivalent ofa small college campus – <strong>for</strong> instance,“God Quad” at Notre Dame includesthe Basilica of the <strong>Sacred</strong> Heart, theGolden Dome, and seven other buildings.In fact, the greatest church in allof Christendom, Saint Peter’s Basilicain Rome, sits on only nine acres whileits piazza takes up an additional nineacres. Twenty acres are huge, but whatare the reasons <strong>for</strong> not building in thecornfield?First, by placing the church out inthe cornfield the parish gives up itsrole in the public square. In historiccities and towns, a church is a beaconof hope and a place of conversion. Inlocating outside of town the churchinadvertently becomes a privatized institutionlike a country club. This is thearchitectural equivalent of hiding itslight under a bushel. <strong>The</strong> parish alsogives up its physical role as leaven ina neighborhood. <strong>The</strong> awareness of theneedy and the ability to serve the poorand the unchurched on a daily basisdissipates in proportion to the distancefrom the center of town. Alternatively,the presence of a church improves thesafety and the harmony of its neighborhood.Second, if an existing parish decidesto move out of town it abandons holyground. Our churches are the sacredplaces in which generations of thefaithful have been baptized, married,and buried. This schism between pastand present is often accompanied bya physical splitting up of the parish.For instance, often times the schoolremains in the village while worshipmoves to the fringe. This is particularlydisruptive to the interaction betweenchurch and school that makes <strong>for</strong> a vibrantparish. After all, the school maynot move out to the new land <strong>for</strong> decades.Third, building out in a cornfieldnormally costs more than building intown. Start with the cost of the land.<strong>The</strong>n add the cost of providing water,sewer, storm-water retention, streets,and parking. <strong>The</strong> additional expense ofbuilding on virgin farmland can quicklycost as much as a million dollars(plus the cost of the land) more thanbuilding in town where utilities anddrainage already exist—not to mentionthe sustainability issues inherent inpaving local agriculture.So, if you have an existing parishand the experts tell you that you needto buy a cornfield, buck the conventionalwisdom and consider the benefits– communal, spiritual, and monetary– of staying in town. Alternatively,if you are founding a new parish,consider being part of a village, evenlocating in a new urbanist community(which often have favorable land andparking costs), or at least try to createa spiritual place within suburbia bybeing integrated with the community.More than parking and playing fields,your parish should be a light to the nationsand a city on a hill.Duncan StroikOctober 2010WCover: Interior of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary, Denton, Nebraska. Photo by Thomas D. Stroka

<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong><strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010C o n t e n t s2 WE d i t o r i a lEditorial . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Duncan StroikN e w s & L e t t e r s3 WWWWRaphael's tapestries on display W Entire church to be moved from Buffalo to Atlanta WRome to build 51 more churches W Church of Saint Malachy restored WDiocese of Orange hires architect <strong>for</strong> new cathedral W World's oldest monastery restored WSymposium on sacred architecture W Cathedral of Charleston receives a new spire W814192426WWWWWA r t i c l e sLost Between Sea and Sky: Review of the Padre Pio Shrine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Matthew AldermanAuthentic Urbanism and <strong>The</strong> Neighborhood Church . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Craig LewisLively Mental Energy: Review of the Seminary of Our Lady of Guadalupe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Denis McNamaraArchitectural Violence in Umbria: Review of "<strong>The</strong> Fuksas Church" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Andrea PaccianiLiturgical Exegesis According to Hugh of St. Victor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Jordan WalesD o c u m e n t a t i o n31 WKeynote Adress to the <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> Conference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . His Eminence Justin Cardinal Rigali3738394041WWWWWB o o k sBeauty of Faith by Jem Sullivan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . reviewed by Chris Burgwald<strong>The</strong> Future of the Past by Steven W. Semes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . reviewed by John H. CluverLiturgical Space: Christian Worship and Church Planning by Nigel Yates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . reviewed by Timothy Hook<strong>The</strong> Politics of the Piazza by Eamonn Canniffe. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . reviewed by Thomas M. Dietz<strong>Sacred</strong> Spaces: Religious <strong>Architecture</strong> in the Ancient World by G.J. Wightmann . . . . . . . . . reviewed by John Stamper42 WFrom the Publishing Houses: a Selection of Recent Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . compiled by <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>w w w . s a c r e d a r c h i t e c t u r e . o r gJ o u r n a l o f t h e I n s t i t u t e f o r S a c r e d A r c h i t e c t u r e<strong>The</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> is a non-profit organization made up of architects, clergy, educators and others interested in the discussionof significant issues related to contemporary Catholic architecture. <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> is published biannually <strong>for</strong> $9.95.©2010 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>.Address manuscripts andletters to the Editor:EDITORDuncan StroikP.O. Box 556Notre Dame, IN 46556voice: (574) 232-1783email: editor@sacredarchitecture.orgADVISORY BOARDJohn Burgee, FAIAMost Rev. Charles J. Chaput, OFM, Cap.Rev. Cassian Folsom, OSBDr. Ralph McInerny +Thomas Gordon Smith, AIAPRODUCTIONPhilip NielsenThomas StrokaMelinda NielsenJamie LaCourtForest Walton<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 20103

N e w s<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> NewsSt. Paul Preaching at Athens is one of theRaphael Tapestries that went on display.On July 14, <strong>for</strong> one night, four tapestriesdesigned by Raphael in 1519 returned totheir original home in Michelangelo’sSistine Chapel—a sight not seen since1983, the 500 th anniversary of Raphael’sbirth. <strong>The</strong>se tapestries from the VaticanMuseums were also displayed atthe Victoria and Albert Museum inLondon alongside the original drawingsby Raphael. <strong>The</strong> exhibit opened onSeptember 8 during Pope BenedictXVI’s visit to Great Britain to celebratethe beatification of John Henry CardinalNewman, and closed October 17.Commissioned by Pope Leo X Mediciin 1515, Raphael illustrated the lives ofSaints Peter and Paul on paper as largeas the finished product—eleven byseventeen feet—and Peter van Aelst, thegreatest weaver of the age, executed thetapestries in Belgium.W<strong>The</strong> Parish of Saint Gerard of Buffalo, NYMary Our Queen Parish of Norcross,GA, plans to buy Saint Gerard’s ofBuffalo, NY. <strong>The</strong> plan has been endorsedby the Catholic archdiocese of Atlanta,the diocese of Buffalo and Saint Gerard’s<strong>for</strong>mer parishioners. According to theproposed scheme, the church will betaken apart, stone by stone, cataloged,trucked south, and rebuilt. <strong>The</strong> majorityof Saint Gerard’s will be reused: theexterior limestone, oak pews, stainedglass, stations of the cross, confessionals,and the granite columns. <strong>The</strong> newchurch will look almost exactly like SaintGerard’s but have a steel skeleton, a newfoundation, floor, roof, HVAC systems,and a bigger choir loft. <strong>The</strong> plasterceiling, including a beautiful Coronationof Mary fresco, will be destroyed inthe demolition. <strong>The</strong> project will taketwo years once it begins. <strong>The</strong> cost isestimated at $15 million, including apayment to the diocese. <strong>The</strong> parish has$3 million and plans to raise and borrowthe rest.Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum,Photo: Wikimedia CommonsSaint Margaret Mary Alacoque, PA.WSaint Margaret Mary Alacoque RomanCatholic Parish celebrated the Riteof Dedication of their new churchin Harrisburg, PA designed by SGSArchitects. <strong>The</strong> church seats 844. <strong>The</strong>$5.2 million dollar “Romanesque” stylechurch sits on almost twenty acres ofland. Total project cost, including land,is approximately $7.1 million.WMadrid Youth Day will feature the 500year old, nine feet tall, Arfe Monstrance,designed by Enrique de Arfe from1517-1524. <strong>The</strong> gold and silver coveredmonstrance is used annually in theCorpus Christi procession through thestreets of Toledo. Francisco Portela,professor of art history at Madrid’sComplutense University, describesit as “the best example of Spanish<strong>The</strong> Arfe Monstrance of Toledo will beused in the during World Youth Day inMadrid.silversmith craft of all times.” <strong>The</strong>monstrance will be used in Eucharisticadoration during the World Youth Dayvigil on Saturday night, Aug. 20, 2011.<strong>The</strong> Youth Day organizers hope thatthis time of Eucharistic adoration will“allow multitudes of young people tocontemplate and to admire a uniquework of art in the world, used accordingto the purpose of its creators, and thus torediscover the value of art in the liturgy.”Holy Trinity Catholic Church ofWestminster, CO completed an additiondesigned by Integration Design Group4 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Photo: stmmparish.orgPhoto: Wikimedia CommonsPhoto: integrationdesigngroup.com

<strong>The</strong> medieval glaziers who createdgold-painted stained glass windowsinadvertently developed a solarpowerednanotech air-purificationsystem. According to Dr. Zhu HuaiYong of the Queensland Universityof Technology in Australia, the goldpaint employed in Gothic stained glasswindows purified the air when heatedby sunlight. “For centuries peopleappreciated only the beautiful works ofart, and long life of the colors, but littledid they realize that these works of art arealso, in modern language, photocatalyticair purifier with nanostructured goldcatalyst,” said Zhu in a statement. Zhusaid that tiny gold particles found inmedieval gold paint react with sunlightto destroy air-borne pollutants likevolatile organic chemicals/compounds(VOCs).<strong>The</strong> "Blue Virgin" window of Chartes,one of the surviving windows from theRomanesque structure, is an exampleof a medieval window that acts as aphotocatalytic air purifier.Photo: Wikimedia CommonsGianni Alemanno, the mayor of Rome hasannounced the plan to build fifty one newCatholic parishes to serve the suburbs ofthe city.Tor Vergata, have been waiting almosteight years to find a permanent home.Now its parishioners will finally haveone. <strong>The</strong>se churches would “not only becenters of worship, but also social andcultural centers <strong>for</strong> the city’s suburbs.”As Mayor Alemanno said, “We arewell aware that parishes are oftenplaces of meeting and identity in cityneighborhoods.” Alemanno has beenone of modern Rome’s most pro-Churchmayors. A re<strong>for</strong>med fascist, he has beenconsistent in his support <strong>for</strong> the Church,not only in practical matters but also inher battles with radical secularism.WOne of Belfast’s oldest and mostbeautiful churches has won a covetedprize following a fifteen monthrenovation project. Saint Malachy’sCatholic Church has been declaredNorthern Ireland Project of the Year. <strong>The</strong>nineteenth century church beat severalPhoto: torrinonews.blogspot.comN e w smulti-million pound commercial andgovernment schemes. Following themajor renovations, many of the church’sold features were recovered. <strong>The</strong>seincluded the altarpieces, the sanctuary,the ornately plastered ceiling, andstained glass. Belfast architecture firmConsarc Design Group led the project.WOn July 5, His Holiness Pope BenedictXVI inaugurated the Saint JosephFountain, the 100 th fountain in theVatican gardens. In his speech he saidthat, “it is a motive of great joy to me toinaugurate this fountain in the VaticanGardens, in a natural context of singularbeauty. It is a work that is going toenhance the artistic patrimony of thisenchanting green space of Vatican City,rich in historic-artistic testimonies ofvarious periods.” <strong>The</strong> fountain exhibitssix bronze panels that display importantmoments in the life of St. Joseph.Photo: Ray O'Connor PhotographyWGianni Alemanno, the mayor of Romeannounced plans to build fifty-one newparishes in the Eternal City, fundedthrough collaboration with the Vicariateof Rome, other dioceses, and landdonations from the city council. It is hard<strong>for</strong> many to imagine Rome needing morechurches, but some parishes, such asSaint Mary Queen of Peace in the suburb<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Pope Benedict XVI recently innagurated the 100th fountain in the Vatican Gardens.5Photo: ecojoekits.com

N e w smore quickly. “It will be very easy<strong>for</strong> this church to be built because thegovernment follows the line that inevery new urban area there should bea church,” explained Bishop AntoniosAziz Mina of Guizeh.a month after Egypt’s worst incident ofanti-Christian violence in over a decade,when a bloody shooting at a church onChristmas Eve killed seven peopleW<strong>The</strong> Diocese of Orange has hired thearchitect who designed Oakland's"Cathedral of Light" (above), CraigHartman of S.O.M.<strong>The</strong> architect who designed Oakland’sinfamously modernistic $190 millionChrist the Light Cathedral has beenselected to come up with plans <strong>for</strong> acathedral complex in Santa Ana, asthe Diocese of Orange hired Craig W.Hartman, FAIA, of Skidmore, Owings &Merrill LLP (SOM) as lead designer <strong>for</strong>the initial phase of this project.Hartman designed the Oaklandcathedral that was consecrated in 2008.<strong>The</strong> Oakland cathedral breaks with thetradition of Catholic sacred architecture;a break with tradition appears to bewhat Bishop Brown hopes <strong>for</strong> in thehiring of Hartman. <strong>The</strong> diocesan pressrelease says that the bishop has: “nointerest in copying the past and willmake every ef<strong>for</strong>t to develop a structurethat respects the environment as muchas it will its people.”In May, Bishop Brown reportedlyasked the Vatican to allow him toserve five years beyond the mandatorycanonical retirement age of seventyfive.Bishop Brown turns seventy-fiveon Nov. 11, 2011, but reportedly wantsto stay on in order to see the cathedralcomplex completed.WNormally it can take as many as thirtyyears and a signature from the presidentto get a new church built in Egypt. That’swhy Coptic Catholics are happy to bebenefiting from a new developmentpolicy that will bring them a churchPhoto: Wikimedia CommonsWOn June 19, 2010 the great Englishrecusant Chapel of All Saints ofWardour Castle opened <strong>for</strong> the day.<strong>The</strong> exhibition included the display ofhistoric vestments and a concert of theeighteenth century organ.WWardour Castle's recusant chapelEgypt’s antiquities chief announcedthe completion of an almost decadelong,$14.5 million restoration of theworld’s oldest Christian monastery—Saint Anthony’s Monastery at thefoot of the desert mountains nearEgypt’s Red Sea coast. Touting it as asign of Christian-Muslim coexistence,the director made the announcementregarding the fifth century monasteryRestoration was recently completed on the Monastery of Saint Anthony, Egypt, theworld's oldest Christian monastery.6 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Photo: wardourchapelexhibition.co.ukWSaint Joseph High School of Trumbull,Connecticut has recently renovated theirchapel.<strong>The</strong> responsibilities of a bishopregarding the opening or closing of aparish are covered in Canon 515, whichwas cited in a recent series of decreesissued by a panel of the Supreme Courtof the Apostolic Signature, the church’shighest court, in deciding the appeals of10 closed parishes in the Archdioceseof Boston. <strong>The</strong> Court’s ad hoc Panel ismade up five cardinals and archbishopsserving on the bench. This recent rulingdecided that Cardinal O’Malley of Bostonfollowed correct procedure and that in thefuture a bishop need only to consult thepresbyteral council be<strong>for</strong>e he acts.WPhoto: Wikimedia CommonsPhoto: Donna Corless

N e w sWOn April 30 through May 1 theUniversity of Notre Dame’s and <strong>The</strong>Catholic University of America’sSchools of <strong>Architecture</strong> cosponsoreda Symposium on the Campus of CUAentitled, “A Living Presence: Extendingand Trans<strong>for</strong>ming the Tradition ofCatholic <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>.” JustinCardinal Rigali delivered the KeynoteAddress. <strong>The</strong> other principal speakersincluded:Duncan Stroik, Notre DameSchool of <strong>Architecture</strong>, Craig Hartman,Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, DenisMcNamara, <strong>The</strong> Liturgical <strong>Institute</strong>,LeoNestor, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> of <strong>Sacred</strong> Musicandthe CUA school of Music, AnthonyVisco, Atelier <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Sacred</strong> Arts.Debate centered on several recurringquestions: Is there an appropriatearchitectural language <strong>for</strong> liturgy?Does the modernistic abstraction andlimitation of art in churches focus oremaciate the liturgy? Can traditionalchurch architecture adapt to modernliturgical needs and contemporarybuilding practices? Are modern andpost-modern architecture based on anti-Catholic world-views? <strong>The</strong>se questions,as addressed in lectures and discussions,helped to highlight the fundamentaldifferences between modernist andtraditional sacred architecture.W<strong>The</strong> "greenest" building in the U.S. is aschismatic "benedictine" chapel designedby the WI firm Hoffman LLC.<strong>The</strong> greenest building in the UnitedStates is a monastery, according to theU.S. Green Building Council. <strong>The</strong>yrecently awarded the BenedictineWomen of Madison’s Holy WisdomMonastery (no longer affiliated withthe Catholic Church) a Platinum LEEDrating with sixty-three out sixty-ninepossible points–the most points ofany certified building in the country;“almost 100 percent of the 60,000-squarefootold Benedictine House was alsorecycled or reused in the buildingprocess.” <strong>The</strong> sisters do carbon fasting<strong>for</strong> Lent, saying, “When the scripturewriters described fasting, they neverenvisioned carbon fasting actions. In2010, however, given our awarenessof reducing our production of climatechange pollution…Photo: benedictinewomen.orgstreet. <strong>The</strong> 8.8-magnitude quake affectedtwo million people in eight of Chile’stwenty-seven dioceses. Over 800 peoplewere killed in the disaster and some500,000 more were displaced. Aid tothe Church in Need reported today thatit is sending thirty-nine tent chapels tothat region to house the church servicesthat are still being held on the streets.Some 80 percent of the churches in thequake-stricken areas were devastated tothe point of being unusable. <strong>The</strong> tents,which were designed <strong>for</strong> easy assembly,cover an area of over 1,990 square feet,with a capacity to seat one hundred.W<strong>The</strong> Parish of Saint Anne in Sherman TX,designed by Fisher and Heck of Dallas wasrecently completed. <strong>The</strong> church seats 750.W<strong>The</strong>re is continued progress in theconstruction of the Abbey of NewClairvaux in Vina, CA as the masons arebeginning the cross-vaulted stone ceilingof the chapter house this year.WPhoto: Wikimedia CommonsWAs Chile continues to rebuild after aFeb. 27 earthquake, tents have been sentto be used as chapels <strong>for</strong> the parishes thathad been <strong>for</strong>ced to hold services on theTent chapels are being employed in Chileafter the earthquake destroyed manychurches.Photo: Church in NeedCharleston's Cathedral of Saint John theBaptist finally recieved a spire after a 103years.<strong>The</strong> Most Reverend Robert E.Guglielmone, Bishop of Charleston,blessed the new spire <strong>for</strong> the Cathedralof Saint John the Baptist on March8, 2010. <strong>The</strong> present Cathedral wascompleted in 1907, but without a spire<strong>for</strong> lack of funds. <strong>The</strong> spire and gildedcross bring the height of St. John's to167 feet.WPhoto: Wikimedia Commons<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 20107

A r t i c l e sLost Between Sea and SkyLooking <strong>for</strong> Padre Pio in Renzo Piano’s Pilgrimage ChurchMatthew AldermanPhoto:Antonio Fragassi<strong>The</strong> entrance of the shrine.It is a perilous thing to ask the saints<strong>for</strong> design advice. <strong>The</strong> apostleThomas earned his patronage ofthe architectural profession by givingaway most of his construction budgetto the poor and was nearly martyred <strong>for</strong>his trouble. And while legend says the<strong>for</strong>mer doubter was hired by the Indianking Gundoferus on account of hisknowledge of ornate Roman classicism,St. Bernard, that great micro-manager ofmonasteries, had very little time <strong>for</strong> thefancies of Romanesque ornamentation,railing against its distractingly frivolouscapitals and grotesques. 1 Ultimately,each church building is not about theearthly taste of its titular but a reflectionof the glorious entirety of the heavenlyJerusalem. Yet the gulf between St. Pioof Pietrelcina, thaumaturge, stigmatist,and occasional flying friar, and the newshrine recently raised over his tombby his countryman, world-famousItalian architect Renzo Piano, is achasm difficult to cross, even by a saintoccasionally known to levitate.<strong>The</strong> Capuchin friar St. Pio of Pietrelcina(1887-1968), better known to hisfilial devotees as Padre Pio, lived a lifemarked by mystical phenomena: ecstasies,diabolical persecutions, bilocation,prophesies, the ability to read men’shearts, and most extraordinarily, theimpression of the stigmata, the woundsof Christ’s passion. In spite of all thesewild spiritual gifts—and the thousandswho came to pray or just to watch—thesaint remained humble and level-headed,devoted to the simple ministries ofa parish priest, the public celebrationof the Mass and the constant hearingof confessions. In the end his sanctitylay not just in miracles but in his lifeof prayer and sacrifice. He was canonizedin 2002 by John Paul II, who manyyears earlier had asked the friar to hearhis confession.Piano describes the new pilgrimagechurch in Padre Pio’s Puglian hometownof San Giovanni Rotondo as a“portrait” of the saint. His conceptionof the saint’s simplicity led him toreject the traditional basilican model ofchurch-planning as smacking too muchof “power” and “grandiloquence,”opting <strong>for</strong> a centralized plan executedin simple wood and local stone. 2 Architecturalcritic Edwin Heathcote, ina glowing Financial Times article on thenew building, describes the shrine’s<strong>The</strong> front doorsinterior as an “embracing shell like aslightly squashed armadillo.” 3 Untilrecently, Padre Pio’s mortal remainsrested in the church of Santa Mariadelle Grazie, a large but plain basilicanstylechurch in a lightly-modernizedRomanesque style, sparingly ornamentedwith touches of marble andmosaic. This more conventional structurewas built during the saint’s lifetimeto accommodate pilgrims visitingthe famous wonderworker.<strong>The</strong> Padre Pio Pilgrimage Shrineseats 8,000, with room <strong>for</strong> 30,000 standingon the parvis outside. It has beendescribed as the second-largest in theworld after St. Peter’s. 4 Dedicated in2004 after more than a decade of planningand with a budget of $51 million,the shrine returned to the media spotlightafter Pope Benedict XVI officiallyopened the church’s crypt, a goldenwalledunderground chamber housingthe saint’s silver sarcophagus. 5 <strong>The</strong> ArchitecturalRecord describes the shrine8 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Photo:Antonio FragassiPhoto:Francesco Tagliomonte

as “an attempt to rationalise anddignify this public urge to venerate aremarkable individual.” 6 While referringprimarily to the medieval zoo ofsouvenir-hawkers and pilgrim hotelsthat now rings San Giovanni Rotondo,journalistic coverage hints at a dissonanceat the heart of the project. Mostcommentators seem more interested indiscussing the building’s relationshipwith the landscape than its status as areligious shrine. Piano has remarked,“I have tried to arrange the vast spacesand surfaces in such a way that thegaze of visitors can be lost between thesky, the sea and the earth.” 7Piano expresses his own religiousopinions less dramatically than hissweeping design proclivities. In an interviewwith the Catholic news serviceZenit, he describes himself as a “Catholicby <strong>for</strong>mation and conviction,”though he adds, somewhat cryptically,“not bigoted.” 8 Piano sought to enterdeeply into Padre Pio’s own religiousexperience. “I […] became a bit of aCapuchin,” 9 he comments, also studyingthe history of liturgy and religion inthe process. Piano’s tutor in the ways ofliturgy was Crispino Valenziano, a professorof liturgical anthropology andspirituality at the St. Anselm Pontifical<strong>The</strong> low arches give one a crowded and earthbound feeling.<strong>The</strong> nataloid plan of the shrine and siteA r t i c l e sLiturgical <strong>Institute</strong> in Rome, and sometimedeputy of <strong>for</strong>mer papal master ofceremonies Piero Marini.<strong>The</strong> building reflects the low,scrubby, rolling terrain all around it,but it does not appear to be nestled inthe landscape so much as lie flaccidlyupon it. Rather than primitively edenic,the effect is ramshackle and faintly industrial.<strong>The</strong> shrine’s most obviousfeature is its broad, nearly flat roof, anirregular and jagged armor of immensepre-patinated copper plates. Beneaththe low, bowed roofline, the structureseems not so much built as assembled,a sagging bricolage of precariouslybalancedstone, wood, glass, metal, andstucco. <strong>The</strong> self-conscious geometrictwists feel, at some level, farmore ostentatious and alienthan the triumphalist ornamentsPiano took great painsto avoid. Indeed, lacking thesense of scale brought by ornamentand detail, the long,low structure has a lumpen,looming quality.<strong>The</strong>re are few obvioussymbols, save a very largefreestanding cross placedoff to one side of the churchinterior. <strong>The</strong> main entranceconsists of two squat bronzedoors covered with spare,pseudo-primitive modernisticsculpture set into a façadeof green metal slats. <strong>The</strong> lowcampanile, built into one ofthe piazza’s retaining walls,is handsome in a strippedclassicalway, although ultimatelyperipheral to theoverall design.<strong>The</strong> interior is a greatlyenlargedvariation on thesame semi-circular plan thathas become ubiquitous insuburban parishes every-Photo:Antonio FragassiPhoto: Contemporary Church Archicture<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 20109

A r t i c l e swhere. Piano’s version is generated bya roughly spiral geometry reminiscentof a nautilus or snail shell. For a shrinededicated to a priest who lived his vocationof alter Christus in the stimata,this departure from a cruci<strong>for</strong>m planis idiosyncratic in the least. <strong>The</strong> architectwas deeply concerned that theenormous interior retain a focus on thealtar while creating within it the smallnessand intimacy necessary <strong>for</strong> prayerand recollection. Piano’s solution wasto divide the interior into a collectionof smaller spaces, each like a separatechurch seating around 400, openingonto the altar at the nexus of the nautiloidcurve, creating a sense of prayerfulprivacy in the midst of a low, openspace. This is an interesting responseto the contemporary trend towardsecclesial giganticism that has led tosuch buildings as the Los Angeles Cathedraland the new church at Fatima.While intriguing in the abstract,the reality of the plan presents seriousphysical and metaphysical difficulties.<strong>The</strong> building’s skeleton of twenty-onespoke-like stone arches radiates, intwo roughly concentric rings, from afunnel-like central hub placed abovethe saint’s crypt-level tomb. <strong>The</strong> altar,set atop a lofty, if narrow, open sanctuary,stands directly in front of thisnexus. Piano explains the arches werean attempt to create “the modernequivalent of a Gothic [sic] cathedral,but to make the arches fly within thespace.” 10 However, the effect is impersonaland uncom<strong>for</strong>tably vast, whilebetween the arches it feels more than alittle claustrophobic. <strong>The</strong> predominantnote is earthbound, linked not with theupward movement of man towardsGod, or God towards man, but towardthe unseen body of the holy man inthe basement, who is treated more likeMerlin than a Christian saint.<strong>The</strong>re is little ornament and lesssacred art. A fabric screen depictingscenes from the Apocalypse by RobertRauschenberg covers the interior of thefront façade’s broad parabolic window.Faintly cartoonish, it is loosely traditionalin its composition and adds a bitof welcome color to the interior, as doesa gradated splash of faded blue on thevault over the altar. 11 For all Piano’sconscientious pursuit of the Franciscanspirit, one is glad that Giotto did notrespond to the same impulse at Assisiwhen St. Francis was still within thereach of living memory. Despite Piano’sconcerns about Franciscan simplicity,his conception of humility might seemmyopic to Padre Pio himself, who worethe simple robes of a Capuchin in dailylife but at the altar obediently clothedhimself in the colorful silk vestments ofa priest of Jesus Christ. It is not a coincidencethat the first notable act ofSt. Francis after his conversion was torestore a little church, San Damiano,to its <strong>for</strong>mer glory. Just as splendordoes not automatically entail waste,conversely—as any architect knows—plainness can be surprisingly expensiveand may suggest not humility butelite faddishness.Rein<strong>for</strong>cing this impression, thesmall sanctuary plat<strong>for</strong>m is almostcrushed by the low curve of the vaultoverhead. On the other hand, the altarcross by Arnaldo Pomodoro is certainlyfuturistic, a chunky block of metalhanging perilously over the altar andresembling a mass of burnished, halfmeltedmachine parts. It also lacks thefigure of Christ.Nestled cleverly in one of the outercurves of the nautiloid, the Blessed SacramentChapel is one of the more intriguingand truly intimate portions ofthe interior. Unlike the centralized arrangementof the main church, it is orientedlongitudinally on a trapezoidalplan. <strong>The</strong> chapel walls narrow subtly,moving the eye towards the tabernacleshrine, set atop a low octagonal plinthof three steps. <strong>The</strong> overall effect is minimalistic,but the warmth and texture ofthe mottled beige walls breathe somelife back into the space.Piano commissioned the late Roy Lichtenstein—famous<strong>for</strong> the deliberatelycartoonish painting entitled Whaam!<strong>The</strong> nearly flat roof is <strong>for</strong>med by an irregular shell of giant pre-patinated copper plates.Photo: wikimedia commons10 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010

<strong>The</strong> tomb of Saint Pio is behind the curved wall.among many other things—to decoratethe shrine’s Eucharistic chapel. Lichtensteinwas working on an image ofthe Last Supper be<strong>for</strong>e his death; Pianoelected not to have another hand completeor replace the painting.<strong>The</strong> tabernacle is an imposing andeven startling object: a pillar of volcanicMount Etna stone standing aloneat the far end of the chapel beneath around skylight high above. 3.5 metersin height, it rises smoothly from asquare base to a faceted octagonal top.Two rows of silver plates representingOld Testament types of the Eucharist orincidents from the life of Christ flankthe sides of the pillar to <strong>for</strong>m a roughlycruci<strong>for</strong>m shape, with the central doorin the <strong>for</strong>m of a silver pelican. Whenopened, the tabernacle doors reveal apair of beautiful, faintly Asiatic representationsof the ichthys sculpted intothe interior. <strong>The</strong> reliefs, while exaggeratedlypseudo-archaic in some details,are <strong>for</strong> the most part well-executed andcompare with some of the more interestingArt Deco work of the LiturgicalMovement period. <strong>The</strong> use of Biblicalparallelism and typology also adds anunexpected dose of sophistication tothe sequence.Yet the overall effect is strangelyuncommunicative. <strong>The</strong> faceless blackstela of the tabernacle hints at some<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010powerful Presence within,but fails to reveal it. <strong>The</strong>shiny stone the color ofdeath seems a peculiarlyinapt color <strong>for</strong> a tabernacle.<strong>The</strong>re are no other furnishingssave the squat, geometricpews in light-coloredwood. Unrelieved by thegleam of hammered silverpresence lamps (or evena pop art Last Supper), itremains alien and even sinister.Admittedly, it is notwithout a sense of otherworldlypower, but at best itis an altar to the UnknownGod, incongruous with theGospels’ revelation. As St.Paul once said, “Whomthere<strong>for</strong>e ye ignorantlyworship, Him declare I untoyou.” 12Passing from theupper church into thecrypt—which holds, somewhatillogically, high-trafficareas like the shrine and theconfessionals—one entersa shiny, glittery realm of recognizableiconography and haloed saints. MarkoIvan Rupnik, the Jesuit artist responsible<strong>for</strong> the Redemptoris Mater Chapelin the Vatican, contributed 2,000 squaremeters of mosaics showing eighteenscenes from the life of Christ, eighteenfrom the life of St. Francis and a finaleighteen from Padre Pio’s life. <strong>The</strong>Photo:Antonio FragassiA r t i c l e scomprehensive quality and parallelismof such a cycle is worthy of much applause.Rupnik’s use of color is refreshing,with rich golds, reds, and intensechemical blues predominating. Afterthe beige upper church, this wealth ofgold, serpentine, jade, and rose quartzcomes as a distinct relief.<strong>The</strong> mosaics are not without theirown shortcomings. <strong>The</strong> recent openingof the church’s lower level has unleashedan outcry in some quarters,with accusations that the lavishlydecorated crypt is wasteful glitter. 13However, the real problem here lies notin the opulence of its materials—SaidJudas to Mary now what will you do/Withyour ointment so rich and so rare?—butthe content and shape of its ornamentationand iconography. One is remindedof the caviar-filled ice swan in BridesheadRevisited—the problem is not thecaviar, but the shape.While ultimately Byzantine in inspirationand straight<strong>for</strong>ward in its use oftraditional symbolism, Rupnik’s signaturestyle lacks the sense of detail andscale necessary <strong>for</strong> such large compositions.<strong>The</strong> effect is somewhat superficialin its recollection of the traditionsof the East, and the figures are tooself-consciously abstracted. <strong>The</strong> mosaicistmight have made a good miniaturistwith his economical sense of<strong>for</strong>m, but here everything looks likequick studies inflated to poster-size.And while the glitter is somewhat of awelcome change from above, the mass<strong>The</strong> gilded crypt has garnered much criticism.11Photo: Charlie Brigante

<strong>The</strong> Tabernacleof gold in this low, over-lit space, canseem oppressively unvarying.<strong>The</strong> saint’s tomb itself is precious inits materials yet rather unprepossessingin shape and setting. <strong>The</strong> tomb isscarcely above eye-level, more an elaborateitem on display than an objectof veneration. If the mosaics are excessiveyet undeveloped, the tomb isopulent though underwhelming. Evenon the saint’s sarcophagus—so oftenan opportunity <strong>for</strong> a complex web ofpersonified virtues, patron saints, andscenes of Biblical parallelism—thereis nothing but a pattern of abstract<strong>for</strong>ms of a mildly Romanesque nature.And while Padre Pio’s body has beenexposed to the faithful in the quiterecent past, all images of the shrinehave so far shown the sarcophagusclosed. While some may find this decorous,it seems a regrettable capitulationto squeamishness <strong>for</strong> a saint whohad Christ’s sacrifice written upon hishands and side.Overall, the fact of modernism’smuteness in the face of traditional religionis inescapable here. <strong>The</strong>re is littlein the church’s structure and detailsto distinguish it from a high-profileconcert hall, while definite momentsbring to mind a cutting-edge airportterminal or a lavishly bleak spa; butPhoto:Antonio Fragassinothing overwhelms the soul with theblinding particularity of the Christianmessage. 14It is easy to decry the kitsch that fillsthe shops of San Giovanni Rotondolike the money-changers in the temple,or scoff at pilgrims who are more entrancedby Padre Pio than Christ. Yet<strong>for</strong> all the desire to create a humblechurch <strong>for</strong> this people’s saint, thisvast new shrine has been shaped lessby folk piety than the by high-profiledictums of a design culture that is notentirely certain what to do with religion.At most the church can attempta sort of fashionable plainness, notwithout a degree of appeal from someangles, but which is often more costlyand momentarily modish than actualsymbolic ornament, and which, beingcontemporary, will swiftly grow old.This is not to say that, had it beendeemed necessary to <strong>for</strong>go the timelessroute of the classical (or even thehumility of the Romanesque), the architectcould not have built a church ina simple but lofty manner. Freed fromengineering gimmicks and fashionablenature-worship, it could have beenclothed in noble materials and enlivenedwith dignified, if monasticallysevere, iconography. Piano’s instincts,moderated by the <strong>for</strong>mative humilityof historic precedent, might have led tosomething truly new.Even if Piano found a cruci<strong>for</strong>mtomb too much <strong>for</strong> the cruci<strong>for</strong>m saintof Puglia, he could have raised a rectilinearhypostyle hall, broad but majestic.A fine model could have been thecathedral at Cordova, one of the fewfully horizontal buildings where stonearches soar. If it were necessary to keepit airy and transparent so the faithfuloutside might participate, he couldhave looked to the open-sided chapelsof early Spanish Mexico, with Franciscanroots of its own. 15 Even Rupnik’smosaics might have found a richmodern precedent in the decoration ofthe modernistic but dignified shrineof Our Lady of the Snows in Belleville,Missouri, and other works of the latepre-Conciliar era. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, thePadre Pio shrine remains obliviousto both the recent, as well as the moredistant, past.One of the more extraordinary miraclesattributed to Padre Pio describesa squadron of Allied bombers sightingthe mystic floating high in the air,accompanied, in one account, by theVirgin and St. Michael. <strong>The</strong> flyboys re-turned to base, muddled and dazed,unable to drop their payload on thetown of San Giovanni Rotondo. 16Renzo Piano has said that he hopes thepilgrim’s gaze will be “lost betweenthe sky, the sea and the earth.” 17 In theshrine, it is perhaps Padre Pio’s veryphysical brand of holiness that is lost;the saint is too potent <strong>for</strong> an age thatprefers its spirituality safely disembodied.WMatthew Alderman is the founder ofMatthew Alderman Studios (matthewalderman.com),which specializes in liturgicalfurnishing design and design consulting.He writes and lectures on ecclesiasticalart and design.1 For the legend of St. Thomas, see Bl. Jacobus de Jacobus’s <strong>The</strong>Golden Legend: Reading on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan(Princeton: Princeton UP, 1993), vol I, 27-35. Bernard’s views onarchitecture can be found in his Apology to William of St. Thierry.2 “Padre Pio’s Shrine as the Architect Sees It: Renzo Piano Talksof Monumental Church in San Giovanni Rotondo.” July 23, 2004.Accessed on April 25, 2010. Available online at: http://www.zenit.org/article-10700?l=english.3 Edwin Heathcote, “On the Fast Track to the Middle ofNowhere: Architect Renzo Piano Talks to Edwin Heathcote aboutHow and Why He is Building the Largest Modern Church inEurope,” Financial Times, June 16, 2001 [London Edition], 8.4 “Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Padre Pio PilgrimageChurch,” www.arcspace.com. No date. Available online at:http://www.arcspace.com/architects/piano/padre_pio/padre_pio.html.Accessed on April 25, 2010.A 2001 article says 7,500. See also Heathcote, 8.5 Jason Horowitz, “Awe (And Maybe Acolytes) from Bold<strong>Architecture</strong>,” New York Times, August 19, 2004, Section E, 3.<strong>The</strong> Gold Coast Bulletin reports it as $51 million; see “Good Faith,Popular Padre,” <strong>The</strong> Gold Coast Bulletin, July 3, 2004, See alsoMichael Day, “Spinning in his Grave? Fury at Glitzy Tomb <strong>for</strong>Revered Saint,” <strong>The</strong> Independent, April 21, 2010. Accessed onApril 25, 2010. Available online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/spinning-in-his-grave-fury-at-glitzy-new-tomb-<strong>for</strong>revered-saint-1949629.html.6 Catherine Slessor, “Divine Intervention: Renzo Piano’s HugeNew Basilica [sic] in Southern Italy Reconciles the Spiritual andPractical Needs of Pilgrims,” Architectural Record, September2004.7 Quoted in “Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Padre PioPilgrimage Church.” arcspace.com. No date. Available onlineat: http://www.arcspace.com/architects/piano/padre_pio/padre_pio.html. Accessed on April 25, 2010.8 “Padre Pio’s Shrine as the Architect Sees It.”9 Ibid.10 Heathcote, 8.11 Ibid, 8. Horowitz himself says it resembles acartoon.12 Acts 17:23.13 See “Worshippers Outraged at Glitzy New Tomb <strong>for</strong> ‘Miracle-Worker’ Padre Pio,” <strong>The</strong> Daily Mail, April 21, 2010. AccessedApril 29, 2010. Available online at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1267679/Worshippers-outraged-glitzy-new-tomb-miracleworker-Saint-Padre-Pio.html.14 Horowitz, 3.15 See Jaime Lara, Christian Texts <strong>for</strong> Aztecs: Art and Liturgy inColonial Mexico (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre DamePress, 2008); and City, Temple, Stage: Eschatological <strong>Architecture</strong> andLiturgical <strong>The</strong>atrics in New Spain (Notre Dame, IN: University ofNotre Dame Press, 2004).16 <strong>The</strong>re are several conflicting versions of this story, thoughPadre Pio biographer Bernard Ruffin thinks it likely there is ahistorical basis to it. See Padre Pio: <strong>The</strong> True Story (Huntington:Our Sunday Visitor, 1991), 253; 324-5.17 Quoted in “Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Padre PioPilgrimage Church.” arcspace.com. No date. Available online at:http://www.arcspace.com/architects/piano/padre_pio/padre_pio.html.Accessed on April 25, 2010.12 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010

<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 201013

A r t i c l e s“Law 119. For the temple of the principalchurch, parish, or monastery, there shallbe assigned specific lots; the first after thestreets and plazas have been laid out, andthese shall be a complete block so as to avoidhaving other buildings nearby, unless it were<strong>for</strong> practical or ornamental reasons.”—<strong>The</strong> Laws of the Indies, 1573,by order of King Philip II of SpainFrom our earliest beginnings as acountry, we have always reservedthe most important and prominentspaces <strong>for</strong> our civic buildings. <strong>The</strong> Laws ofthe Indies, as the first specific set of rulesgoverning the settlement of a new townin the new world by Spanish colonists,decreed that three things must happenbe<strong>for</strong>e any other: the identificationof the highest and best location <strong>for</strong>the main plaza, the establishment ofstreets that were to radiate out fromthe plaza in ordinal directions, andthe reservation of the first lots <strong>for</strong> theestablishment of churches (specifically,the Catholic church). Numerous townsin the southeast and southwest UnitedStates were established according tothese principles including Santa Fe andAlbuquerque, NM, Fernandina, FL, andTucson, AZ.This high regard <strong>for</strong> the primacy ofpublic spaces and civic buildings continuedthroughout much of the earlyyears in American urban development.<strong>The</strong> New England town square wasthe Puritan’s <strong>for</strong>m of Spanish plazaand was often flanked by a Protestantchurch. Cathedrals continued to beconstructed in prime locations in viewsof the waterfronts to greet arrivingvisitors, or on hilltops so as to be seenby the entire village or city. In urbanneighborhoods throughout the country,churches were constructed to serve thevarious ethnic immigrant populationsthat would settle in a particular area,becoming a spiritual, social, and—through parochial schools—educationalanchor. Together with parks orplazas, churches <strong>for</strong>med the essentialpublic realm of many a neighborhoodthroughout the county.Authentic Urbanismand the Neighborhood ChurchCraig Lewis<strong>The</strong> church’s slidefrom architectural preeminencein neighborhoodsand in citiesoccurred over a longperiod. Rather than asingle cause, it is morelikely that a series ofgradual shifts—primarilydemographic and economic—slowlyamassedto conspire against whatwas once the norm.<strong>The</strong>se shifts impactedthe construction of otherpublic buildings as well.<strong>The</strong> last considerationof the importanceof the public realmcame during the "CityBeautiful" movement ofthe late nineteenth andearly twentieth centuries(and the parallel"Garden City" movementoccurring in Great Britain). Advocatessought to clean up many ofthe country’s larger cities through theimposition of beautiful landscapesand monuments. While important as adesign philosophy, its moral and socialgoals lacked the spiritual dimension.As a result, few churches were incorporatedinto plans, finally ceding theirlong-standing role as important neighborhoodanchors to more humaniststructures such as museums, libraries,and government buildings.After the end of World War II, theexplosion of the suburban developmentpattern and its focus on efficiencyand privacy rang the final deathknell. Public space and public buildingswere no longer a component ofdevelopment patterns and competed<strong>for</strong> land left over from private development.Because our suburbs, as thepredominate development patternacross the United States (and exportedworldwide) have sprawled in this lowdensity,auto-dependent land<strong>for</strong>m, ourcivic facilities have been <strong>for</strong>ced to buildfurther away and bigger as a means toattract more students, parishioners, orcongregants.<strong>The</strong> Chapel at Seaside, FL<strong>The</strong> overall decline in church attendance,coupled with the massive suburbanmigration that nearly emptiedmany urban neighborhoods, has leftmany sacred buildings today with decliningor non-existent populations.Older urban areas like Buffalo, Detroit,Cleveland, and Saint Louis have seenurban churches closing down at analarming rate. Historically CatholicSaint Louis maintains a list of 111parishes closed in recent history, andBuffalo has closed 77 parish churchesand schools since 2005. 1Yet while churches are closing insome locations, they continue to growin others. But unlike their urban,in-town counterparts, these campusesmust accommodate exceptionallylarge facilities, classroom and officebuildings, and occasionally a school.Perhaps, most important, these largesites must accommodate the fact thatevery single person that attends Masswill arrive by automobile, a fact thatensures that a large percentage of everycapital dollar must be relegated to theconstruction of a parking lot ratherthan on the architecture of its buildingsor the ministries that they provide.14 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Photo: Josh Martin

New Urbanism and the NeighborhoodChurchIn October, 1993, approximately170 designers and developers gatheredin Alexandria, VA to discuss thetravails of “the placelessness of themodern suburbs, the decline of centralcities, the growing separation in communitiesby race and income, thechallenges of raising children in aneconomy that requires two incomes<strong>for</strong> every family, and the environmentaldamage brought on by developmentthat requires us to depend on theautomobile <strong>for</strong> all daily activities.” 2Under the leadership of Peter Calthorpe,Andres Duany, Elizabeth Moule,Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, StefanosPolyzoides, and Daniel Solomon—allarchitects—the Congress <strong>for</strong> the NewUrbanism was <strong>for</strong>med and has quicklyrisen to the preeminent organization<strong>for</strong> addressing the “confluence of community,economics, and environmentin our cities.” 3At its heart, New Urbanism is amovement about reclaiming the publicrealm–our streets, our parks, and ourpublic buildings–and ordering the remainderof the land to complementthese critical amenities. However, it isimportant to note that New Urbanismrecognizes “that physical solutions bythemselves will not solve social andeconomic problems, but neither caneconomic vitality, community stability,and environmental health be sustainedwithout a coherent and supportive<strong>The</strong> New Town at Saint Charles, MO<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010framework.” 4New urbanists havelong asserted the needto reserve prominentlocations within newneighborhoods <strong>for</strong> theerection of variouscivic buildings—townhalls, fire stations,school, museums,and churches. <strong>The</strong>challenge until nowhas been <strong>for</strong> many tofigure out a meansby which the verticalinfrastructure of thecivic building can onceagain be integratedinto the neighborhoodafter more than a halfcenturyof movingaway from it. Will congregationssacrifice theexpansive greenfieldcampus with generous parking lots <strong>for</strong>a more urban location? And perhapsmore importantly, can the re-insertionof the neighborhood church be morethan a programmatic alternative to thecommunity clubhouse and truly fulfillthe spiritual needs of the neighborhood’sresidents?If You Build It, Will <strong>The</strong>y Come?Seaside, FL, the traditional neighborhoodoften considered the epicenter<strong>for</strong> the New Urbanist movement,reserved a location <strong>for</strong> a chapel in itsearliest plans. While the neighborhoodA r t i c l e s<strong>The</strong> chapel in the New Town at Saint Charles, MOPhoto: www.newtownatstcharles.comgrew up around this site since 1981, itwasn’t until October 20, 2001 that theSeaside Interfaith Chapel was dedicated.Envisioned by developers Robertand Daryl Davis to be “a place <strong>for</strong> allfaiths to worship,” the 50 foot tall,traditionally-designed structure withits 68 foot tall bell tower anchors thenorthern terminus of Seaside’s centralgreen. <strong>The</strong> multi-function building hasbeen a home to a wide variety of activitiesincluding weddings, lectures,and faith-based services. For a numberof years it was used extensively by anevangelical Christian congregation, althoughthey have since moved on toanother slightly larger location abouta mile away. During the time that congregationwas in residence, “the chapelwas as alive as it has ever been,” accordingto Robert Davis. Since thattime, the chapel has been shared by afew feeder churches from Birmingham,Atlanta, and elsewhere during thesummer months to serve their congregantswho vacation in the resort community.<strong>The</strong> New Town at Saint Charles inSaint Charles, MO, a suburb of SaintLouis, similarly constructed a chapelto serve as their neighborhood’s centerpiece.Presently, the highly prominentclassical structure is the missionof a nearby Lutheran congregation,and shares time with a heavily bookedwedding schedule. It is the weddingbusiness that funds the operations andmaintenance of the building. <strong>The</strong> restof the week, the building sits largely15Photo: Josh Martin

A r t i c l e svacant and devoid of life.As Eric Jacobson, a Presbyterianpastor and the author of Sidewalks inthe Kingdom: New Urbanism and theChristian Faith, noted in an article inNew Urban News in April/May 2005,“When economies of scale allow andthe developer is interested in includinga religious building as an amenity,a multi-faith structure is often less thanoptimal. A generic religious buildingdoesn’t enliven the space nearlyas much as one in which a flesh-andbloodcongregation makes a significantinvestment.” 5 <strong>The</strong> experiences of theNew Town Chapel and Saint CharlesChristian Church certainly bear out hisstatement.Since early experiments in multipurposechapels underper<strong>for</strong>med theoriginal intentions to help authenticate“community,” a number of developershave now begun to reserve spaces <strong>for</strong>the purpose-built church by a specificfaith community.Forging a New CongregationIn the I’On neighborhood of MountPleasant, SC, developer Vince Grahamlong hoped to find a congregation tobuild within the celebrated new urbanistvillage. After an article in the localpaper that noted that the neighborhoodhad a civic site reserved, members ofthe Orthodox Church in America approachedVince with a proposal tobuild a new home <strong>for</strong> their parish.Enamored with the rich architecturalheritage that the Orthodox faith carrieswith it through each of their buildings,the proposal was quickly accepted.<strong>The</strong> land was donated to Holy AscensionOrthodox Church and in May,2008, the 3,500 square foot, Byzantinestructure was dedicated. Interestingly,the parish took up residence in theneighborhood long be<strong>for</strong>e the church’sdedication by maintaining a Christianbookstore, Ascension Books, in an adjacentstorefront. It was through thisearly presence in the neighborhoodthat the parish built a connection withmany of the neighbors and merchants.Those “friends of the parish” helpedto build the church literally throughsuch tasks as driving the nails into thefloor. And the neighborhood continuesto support the church through itsattendance at various social and culturalgatherings held at the church.Father John Parker, the parish’s firstand current pastor, believes that theirunique and <strong>for</strong>mal liturgy is as immediatelyattractive to the general populationas a non-denominational <strong>for</strong>matwould be. “But,” he adds, “we feel thatwe are able to evangelize every daythrough the art and iconography of thebuilding as they walk, bike, and driveby. In this manner we are able to servetheir specific needs of an Orthodoxfaith if they are so inclined but we viewour mission simply to invite people tobe in the orbit of the church.”Designed by Andrew Gould, the$1.3 million Holy Ascension Churchhas become a true neighborhood landmarkreplete with the onion-domes inthe orthodox tradition and, accordingto Father John Parker, “a perfect orientationof the structure to the east.” <strong>The</strong>latter of these is a designer’s challengewhen given a lot not much larger thana postage stamp in an urban neighborhood.In addition, the size of the lotprecluded many of the suburban amenitiesthat are commonplace with mostchurches, including large parking lots.On-street parking and parking in thenearby town center lots accommodateparishioners’ cars.Today, everyone who comes intothe church, whether as a guest, a patronof the many events that are hostedthere, or <strong>for</strong> <strong>The</strong> Divine Liturgy, hastwo reactions upon entering the smallbuilding–“wow” and “wow.” Whilethey are not a fast growing parish,Father John rests his faith in God inmore subtle ways: “We hope that ourbuilding will be a beacon to those whomight not otherwise come in <strong>for</strong> theliturgy… I believe that beauty will savethe world.”Finding a New HomeSaint Alban’s Episcopal Churchin Davidson, NC and the Church ofthe Good Shepherd in Covington, GAfound new life amidst the front porchesand tree-lined streets of their traditionalneighborhoods.In Covington, the local Episcopalchurch was already looking to relocatefrom their current in-town location toa new site that could better accommodatetheir long-term needs. When theylearned that a site had been reservedby the developers of Clark’s Grove approximatelyone mile from the church’sHoly Ascension Orthodox Church in Mount Pleasant, SCPhoto: Josh MartinPhoto: Josh Martin16 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010

present location, they knew that it wastheir destiny. Interestingly, there wasno civic site available in the secondphase of the neighborhood, but becausethey were still early in the process, thedevelopers tweaked the lots to createa site that accommodated the needs ofthe church. Today the $2.6 million, 240seat church and separate administrationbuilding sit prominently on thethird tallest hill in town.Unlike Holy Ascension, they havea small parking lot, but they still relyheavily on on-street parking to satisfytheir needs. It’s a bit ironic since theprimary reason <strong>for</strong> their initial decisionto relocate was the absence of parking.“It’s a different mindset than the suburbanmegachurch,” observes its rector,Father Tim Graham. “We are muchmore connected because we are righthere in the neighborhood.” A numberof parishioners walk to the churchtoday—in fact more than when theywere located downtown—and theyhope that as the 300 home neighborhoodbuilds out over its over 90 acresthat many more will be attracted to thechurch. Father Tim believes that manypeople across the country “are longingto know their neighbors. <strong>The</strong> neighborhoodchurch can offer not only a placeto worship but also a social network aswell.”Also unlike the very high-pricedhomes in I’On, which is relativelyisolated from its neighbors, Clark’sGrove is a piece of the larger neighborhood.Frank Turner, who leads thedevelopment team, is quick to pointout that “not too far from the uppermiddle class homes of Clark’s Groveare some of the poorest people in theentire country.” Accordingly to FatherTim, “the location in the middle ofthis diverse neighborhood af<strong>for</strong>ds thechurch the responsibility to reach outto everyone.”And finally in Davidson, NC aninfill neighborhood is home to SaintAlban’s Church, within walking distanceof the downtown and DavidsonCollege. What started as a land swapto better orient an entrance became afabulous partnership between the localchurch and the developer to createa very prominent landmark. WhenDoug Boone began planning his “newneighborhood in old Davidson” (heintentionally didn’t name the neighborhood),he and his design team wereable to negotiate a mutually beneficialland swap that would increase the<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010St Alban's Episcopal Church in Davidson, NCchurch’s property from two acres toseven, and place them at the terminationof the main entrance to the neighborhood.From this point on, as thethen-rector of the parish, Gary Stebernotes, “it was all providential.”<strong>The</strong> then-150 person congregationwas able to construct the 300 seat, $1.8million church and bell tower and dedicateit on October 21, 2001; coincidentallya day after the dedication of theSeaside Interfaith Chapel. “Since thattime,” says current rector Father DavidBuck, “the parish has grown to morethan 500 regular attendees over twoservices and more than 1,000 peopleconnected to the church.” Its currentlocation is a fulfillment of the originalmembers’ desire to be seen throughoutthe community. Formerly worshippingin a house located deep in a neighborhoodnot too far from their presentlocation, Saint Alban’s is very much acenter of activity <strong>for</strong> the entire community.Today they host a robust scheduleof music that is open to the community,which included a recent concertby noted pianist, George Winston.<strong>The</strong>y are also beginning a communitygarden as a way to further reachout to the surrounding neighborhoodand host the neighborhood associationmeetings. And finally, in a measurethat harkens back to the multi-faithchapels noted earlier, they provide useof their facility to Temple Beth Shalomof Lake Norman on a regular basisuntil its congregation can build a permanenthome of their own.<strong>The</strong> Canary in the CoalmineEf<strong>for</strong>ts to restore the neighborhoodchurch are still more the exception thanthe norm. New churches in traditional,walkable neighborhoods are few innumber compared to the total numberof new church buildings. But in somevery important ways, these early experimentsare the canaries in the coalmine,indicating that the trend may be successfuland sustainable. While housing,jobs, and shopping have long since returned,churches have hereto<strong>for</strong>e beenmuch more cautious.What New Urbanism presents to thechurch is an opportunity. Very simply,it is an opportunity to override thepattern of auto-dependent, sprawlingcampuses in the greenfields in favorof returning to the neighborhoods,and once again become importantsocial and spiritual anchors. In doingso, the neighborhood church providesvisual beauty, physical prominence,and the restoration of authentic urbanismalongside a physical return of thesacred and the spiritual to our dailylives. Most importantly, the neighborhoodchurch can begin to once againfulfill its role in proclaiming the wordof God within walking distance of ourfront porch.WCraig S. Lewis is the Principal of LawrenceGroup Town Planners and Architects inDavidson, NC. www.thelawrencegroup.com1 For Saint Louis, see: http://www.archstl.org/archives/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=79&Itemid=1For Buffalo, see: http://www.cleveland.com/religion/index.ssf/2010/02/buffalo_catholic_diocese_finds.html2 Congress <strong>for</strong> the New Urbanism, Charter of the New Urbanism(New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 1.3 Ibid., 2.4 Ibid., v.5 Eric Jacobson, “<strong>The</strong> Return of the Neighborhood Church,” NewUrban News (April/May 2005): www.newurbannews.com/churchinsideapr05.html.17Photo: Josh Martin

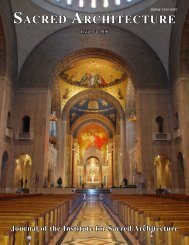

A r t i c l e s“Lively Mental Energy”Thomas Gordon Smith and the Our Lady of Guadalupe SeminaryDenis McNamara<strong>The</strong> seminary is located in the countryside near Lincoln, NE.Though broadcast live on Catholictelevision, the March 2010consecration of the Chapel ofSaints Peter and Paul at the PriestlyFraternity of St. Peter’s Our Lady ofGuadalupe Seminary in Denton, NEpassed rather quietly in the architecturaland ecclesiastical news. Liturgicallyorientedblogs covered its four-hourconsecration ceremony and Churchwatchers noted the many illustriousprelates in attendance. While a joyousday <strong>for</strong> the Fraternity, the chapel alsoserves as an important signpost markingthe coming of age of today’s use of theclassical tradition. While neither thefirst nor the largest of the New Classicalchurches to be completed in recent years,it proves a significant milestone <strong>for</strong> itsarchitect, Thomas Gordon Smith, anintellectual powerhouse and pioneering<strong>for</strong>ce in the return of classicism to thearchitectural profession. Smith hasdrawn from the classical tradition asinspiration <strong>for</strong> his artistic talent, goingbeyond the laudable goal of merecompetence in the classical language,and rising to what author Richard Johnhas described as “the excitement of theclassical canon.” 1An accomplished painter, furnituredesigner, historian, and author, Smithis widely known <strong>for</strong> refounding theSchool of <strong>Architecture</strong> at the Universityof Notre Dame in 1989, makingthe school an incubator <strong>for</strong> a renewalof classical architecture. Notre Damehas since turned out a new generationof young designers who have realistichopes of building classical buildings.This happy situation comes in starkcontrast to that of many of their teachers,who, like Smith, had to run againstthe grain of the modernist architecturalestablishment and learn classicalarchitecture largely on their own.Smith, born in 1948, is simultaneouslypioneer, elder statesman, and a leadingpractitioner in the burgeoning fieldof New Classicism. <strong>The</strong> Our Lady ofGuadalupe Seminary chapel displaysthe compelling fruit of many hardwonand carefully argued discussionsbegun decades ago.Rediscovering the Heritage ofClassicismWhile it may seem to have snuckup on those interested in traditionalchurch design, a burst of traditionalchurches has been completed or is onthe boards from architects like EthanAnthony, James McCrery, DavidMeleca, and Duncan Stroik amongmany others. Almost unthinkableeven as little as ten years ago, buildingslike Stroik’s Thomas AquinasCollege Chapel or Meleca’s Church ofSaint Michael the Archangel in Kansas(both completed 2009), seem to haveglided rather easily into today’s architecturaldiscussion and even some ofthe mainstream architectural press. Buttoday’s successes in traditional ecclesiasticaldesign did not come withoutdiligent attention and hard-foughtbattles. Thomas Gordon Smith has notonly been treating classicism as a livingdiscourse <strong>for</strong> over thirty years, butunlike many other classical architectswho tend to focus on secular society’sclients and commissions, has broughthis knowledge to both academia and tothe Church.Richard John’s 2001 monograph,Thomas Gordon Smith: <strong>The</strong> Rebirth ofClassical <strong>Architecture</strong>, aptly portraysSmith’s early years as both a postmodernistand later a true pioneer inthe move to serious engagement withclassical design. It is easy to <strong>for</strong>get, especially<strong>for</strong> today’s under-<strong>for</strong>ty (andperhaps even under-fifty) generationof classical architects and clients, thattoday’s New Classicism emerged notonly from the anti-historical trendsof modernism, but was further siftedfrom postmodernism’s tentative andironic use of classical <strong>for</strong>ms. Smith’s18 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Photo: Alan SmithPhoto: www.fssp.org/en/photos.htm

invitation to participate in the nowfamous 1980 Venice Bienniale, an internationalarchitectural exhibitionentitled “<strong>The</strong> Presence of the Past,”not only publicized his abilities, buthighlighted his departure from thepost-modern tendency to see classical<strong>for</strong>ms as witty oddities inserted intonew buildings in uncanonical ways.At the exhibition, “Smith was almostalone in adopting a literate treatment”of classical <strong>for</strong>ms, earning the ire ofsome, but also the praise of architecturaltheorist Charles Jencks, who wrote:“Smith is the only architect here totreat the classical tradition as a livingdiscourse.” 2 Smith’s proposed design,<strong>for</strong> instance, required the fabricationof spiraled Solomonic columns whichthe exhibition contractor lacked theknowledge to construct. Rather thanchange his design, Smith returned toold sources: books on the subject byVignola, Guarini, and Andrea Pozzo.“Using the same treatises as architectshad three centuries earlier,” gaveSmith “insight into how the classicaltradition had been continually developedin the light of contemporary circumstancesand then handed on fromgeneration to generation.” 3 Almosttwenty years later, the Fraternity ofSt. Peter found in Smith a man who,like the Fraternity itself, had made aspecialty of “quietly battling trends,”and could build a seminary “withthe irony-free rigor of an ancient.” 4Our Lady of Guadalupe SeminaryAlthough the Our Lady ofGuadalupe Seminary’s chapel was onlycompleted this year, its roots extendback to the late 1990’s, a time whendesigning a large, classically-inspiredbuilding complex seemed by many tobe almost as trend-defying as the promotionof what was then called the TridentineMass. Though Smith had beenusing classical design <strong>for</strong> homes <strong>for</strong>nearly two decades, the mainstreamecclesiastical culture of the time wasfar from accepting traditional architecture.<strong>The</strong> inherent respect <strong>for</strong> traditionevident in the mission of the PriestlyA r t i c l e sFraternity of St. Peter made classical architecturea natural match <strong>for</strong> their lifeand liturgical practice. But the bustle oftoday’s classical revival was just beginningto simmer at the time. <strong>The</strong> architecturalinstructions of the new GeneralInstruction of the Roman Missal, whichwould be released in 2002, had not yetarrived. Several of today’s middle generationof young classical architecturalpractitioners, many centered at NotreDame, were just beginning to coalescean alliance with a similarly pioneeringgroup of liturgical scholars. Mostimportantly, the profoundly anti-traditional1978 document on liturgical architecturepublished by the AmericanBishops’ Committee on the Liturgy,Environment and Art in Catholic Worship(EACW), was still dominating the liturgicalestablishment. Along with someothers, Smith wrote and spoke publiclycritiquing the document, rightly characterizingit as “outdated in its promotionof bland modernist structures andiconoclastic liturgical settings.” 5 Justas he was beginning the design <strong>for</strong> the<strong>The</strong> seminary and newly completed chapelPhoto: Tom Stroka<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 201019

A r t i c l e s<strong>The</strong> seminary entranceseminary in the late 1990’s, Smith publisheda telling article which summarizedhis design method. Turning thelong-established modernist critique onits head, he wrote:"We need not passively accept whatour recent ancestors have dictated. Ifwe apply what the Roman architectVitruvius called “lively mentalenergy,” we can innovativelycontradict the prevailing orthodoxyof abstraction and revive over twomillennia of tradition. <strong>The</strong> thesisthat has defined the life work ofmany architects, including mine,is this: to make traditional <strong>for</strong>msof architecture vitally expressivetoday. Since I began to studyarchitecture <strong>for</strong>mally in 1972, andin my professional and academiclife since, my objective has been tobreak through the barriers that havebeen set up by modernists to makeour <strong>for</strong>ebears seem inaccessible." 6With a client ready and willing to“foster buildings that fully honor thevision and legacy of the Church,” planning<strong>for</strong> the new seminary began.<strong>The</strong> 1998 ground-breaking initiatedthe first stage in Smith’s plans<strong>for</strong> the seminary. <strong>The</strong> Fraternity asked<strong>for</strong> a building complex based onRomanesque precedent, which gaveSmith a wide array of design optionsdrawing from the late antiqueto the early Middle Ages.In 1998, as today, a basilican-plannedchurch madea strong statement aboutcommitment to traditionalworship practice and loyaltyto Rome, both importantpoints <strong>for</strong> the Fraternity ofSt. Peter, then only ten yearsseparated from the schismaticSociety of St. Pius X. Becauseof its expanses of unadornedwalls and restrained use o<strong>for</strong>nament, Romanesque architecturehad been longnoted <strong>for</strong> conveying strengthand grandeur with a relativelymodest expenditure.Smith noted the advantagesof the Romanesque mode,which he said lent “durabilityand economy” and “straight<strong>for</strong>wardsimplicity of <strong>for</strong>m”to new buildings. 7 Smithnoted that <strong>for</strong> his clients, “theRomanesque represents solidity,simplicity, and religious vitality”which is “similar to the way in whichCounter-Re<strong>for</strong>mation patrons and architectssought to reconnect with earlyChristian models.” With a limitedbudget, the Romanesque could givethe Fraternity “discrete, well-proportionedbuildings without striving <strong>for</strong>excesses.” 8Smith’s evocative watercolors of thecomplex received wide publication, hispainterly style demonstrating not onlyhis skill as an artist who holds a degreein painting, but whose approach totraditional architecture depends onthe excitement of expressive color andline. Smith chose to show one view ofthe building in a winterscene, where the shadesof purple and blue insnowy shadows harmonizedwith the multipleshades of yellow andorange found in the brickof the building itself.Here again Smith showedthe creative reworking ofthe classical inheritance:the gold and orange tonesso typical of sunny Italynonetheless work simultaneouslywith Nebraska’ssnowy winter landscapeand the dry grassyplains of its late summer.Photo: Tom StrokaSmith’s attention to locale furthershows that a careful practitioner ofNew Classicism designs a new building<strong>for</strong> its time and place. <strong>The</strong> complexwas carefully sited in the landscape,“situated on the spur of a hill withwings nestled into adjacent ravines.”Smith’s goals, he wrote, were “to createa building complex that appears tohave always existed in this location,”where the prominent site would bevisible from a great distance, and tomake the chapel readily identifiable. 9Smith’s descriptions of his own workindicate that he values clarity of partsand legibility of use. Calling the seminarycomplex a “microcosmic city <strong>for</strong> areligious community,” he designed thearchitecture to convey symbolically thecommunity’s spiritual objectives.To that end, even a quick overviewof the design makes clear the hierarchicalpriorities of the community. <strong>The</strong>cruci<strong>for</strong>m basilican chapel, nearly freestandingexcept <strong>for</strong> a small connectingcorridor, steps <strong>for</strong>ward as the immediatepublic face of the complex, indicatingthe public nature of the chapel andthe importance of the worship within.<strong>The</strong> primary entrance to the seminaryproper is located in the westernwing, delineated by a gabled portalthat Smith calls a “frontispiece.” <strong>The</strong>medieval-inspired Romanesque entrywith receding arches on colonnettessits below a thermal window drawnfrom ancient Rome, all within a Renaissance-inspiredtemple front motif indicatedby strip pilasters of contrastingcolor. Here a somewhat reserved andeconomically built facade draws fromseveral different centuries <strong>for</strong> inspiration,yet maintains a tranquil unity ofdesign that gives no hint of self-con-<strong>The</strong> refectory20 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> 18 2010Photo: Tom Stroka